Things are looking good so far: we’ve got a grid-based layout, one that doesn’t sacrifice complexity for flexibility. I have to admit that the first time I figured out how to build a fluid grid, I was feeling pretty proud of myself.

But then, as often happens with web design, despair set in. Currently, our page is awash in words, and little else. Actually, nothing else: our page is nothing but text. Why is this a problem? Well, text reflows effortlessly within a flexible container—and I don’t know if you’ve noticed, but the Internet seems to have one or two of those “image” things lying around. None of which we’ve incorporated into our fluid grid.

So what happens when we introduce fixed-width images into our flexible design?

Going back, back to markup, markup

To find an answer, let’s do another quick experiment: let’s drop an image directly into our blog module, and see how our layout responds. The first thing we’ll need to do is to clear some space for it in our markup.

Remember our little blockquote, comfortably tucked into

our blog article? Well, we’ve got way too much text on this

darned page, so let’s replace it with an inset image:

<div class="figure">

<p>

<img src="robot.jpg" alt="" />

<b class="figcaption">Lo, the robot walks</b>

</p>

</div>

Nothing fancy: an img element,

followed by a brief but descriptive caption wrapped in a b

element. I’m actually appropriating the HTML5

figure/figcaption tags as class names in this

snippet, which makes for a solidly semantic foundation.

(Sharp-eyed readers will note that I’m using a b element

for a non-semantic hook. Now, some designers might use a span

element instead. Me, I like the terseness of shorter tags like

b or i for non-semantic markup.)

With that HTML finished, let’s drop in some basic CSS:

.figure {

float: right;

margin-bottom: 0.5em;

margin-left: 2.53164557%; /* 12px / 474px */

width: 48.7341772%; /* 231px / 474px */

}

We’re creating a nice inset effect for our figure. It’ll be floated to the right, and will span roughly half the width of our article, or four columns of our flexible grid. Markup: check; style: check. Of course, all this HTML and CSS is for naught if there isn’t an actual image available.

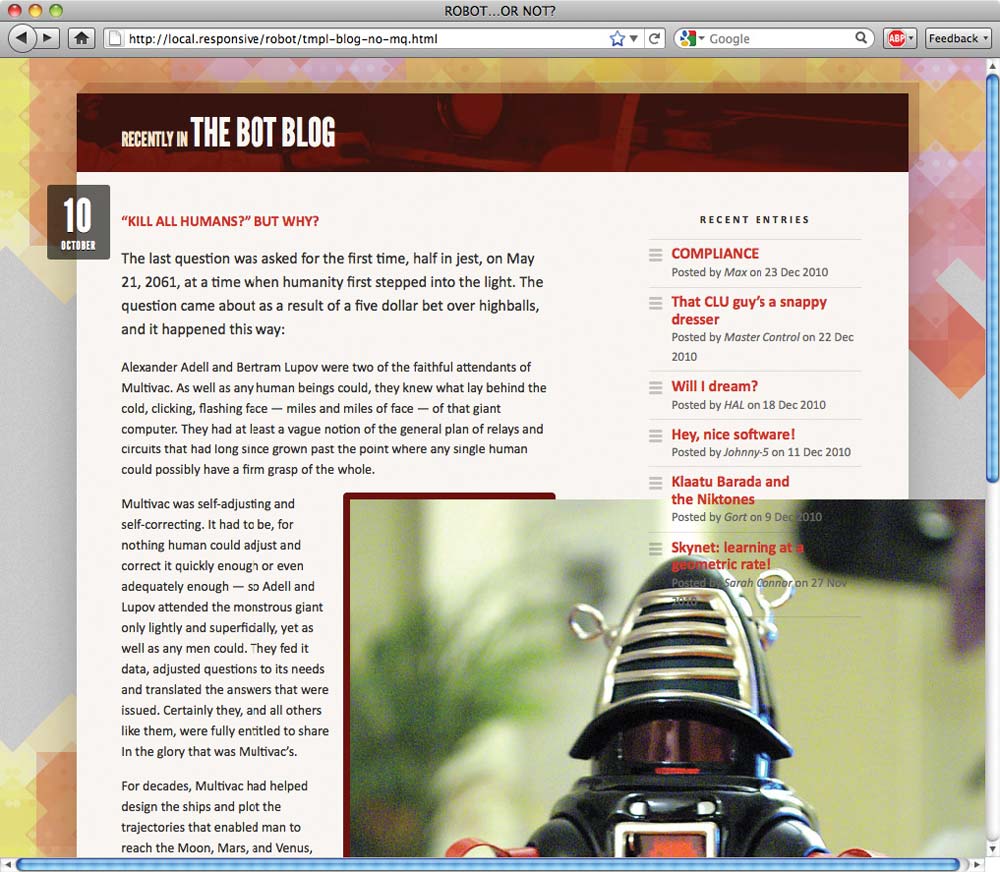

Now, because I love you (and robots) dearly, not just any image will do. And after scouring the web for whole minutes, I found a fantastically imposing robo-portrait (FIG 3.1). The beautiful thing about this image (aside from the robot, of course) is that it’s huge. I’ve cropped it slightly, but I haven’t scaled it down at all, leaving it at its native resolution of 655×655. This image is much larger than we know its flexible container will be, making it a perfect case to test how robust our flexible layout is.

FIG. 3.1: An appropriately botty robot pic, courtesy of Jeremy Noble (http://bkaprt.com/rwd/10/).

So let’s drop our oversized image onto the server, reload the page, and—oh. Well. That’s pretty much the worst thing on the internet (FIG 3.2).

FIG 3.2: Our huge image is huge. Our broken layout is broken.

Actually, the result isn’t that surprising. Our layout isn’t broken

per se—our flexible container is working just fine, and the

proportions of our grid’s columns remain intact. But because our image is

much wider than its containing .figure, the excess content

simply overflows its container, and is visible to the user. There simply

aren’t any constraints applied to our image that could make it aware of

its flexible environment.

Fluid images

But what if we could introduce such a constraint? What if we could write a rule that prevents images from exceeding the width of their container?

Well, here’s the good news: that’s very easy to do:

img {

max-width: 100%;

}

First discovered by designer Richard Rutter

(http://bkaprt.com/rwd/11/), this

one rule immediately provides an incredibly handy constraint for every

image in our document. Now, our img element will render at

whatever size it wants, as long as it’s narrower than its containing

element. But if it happens to be wider than its container, then the

max-width: 100% directive forces the image’s width to

match the width of its container. And as you can see, our image

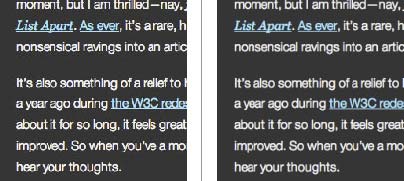

has snapped into place (FIG 3.3).

FIG 3.3: Just by

including max-width: 100%, we’ve

prevented our image from escaping its flexible container. On a related

note, I love max-width: 100%.

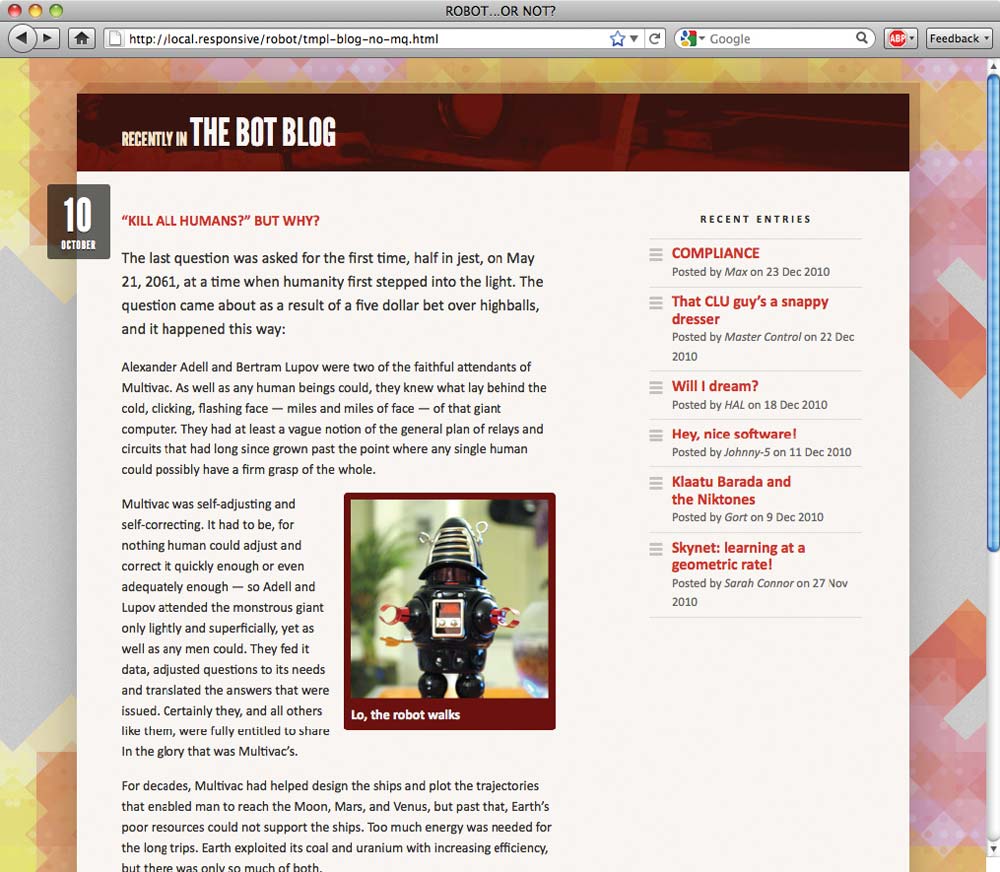

What’s more, modern browsers have evolved to the point where they resize the images proportionally: as our flexible container resizes itself, shrinking or enlarging our image, the image’s aspect ratio remains intact (FIG 3.4).

FIG 3.4: Regardless of how wide or small its flexible container becomes, the image resizes proportionally. Magic? Who can say.

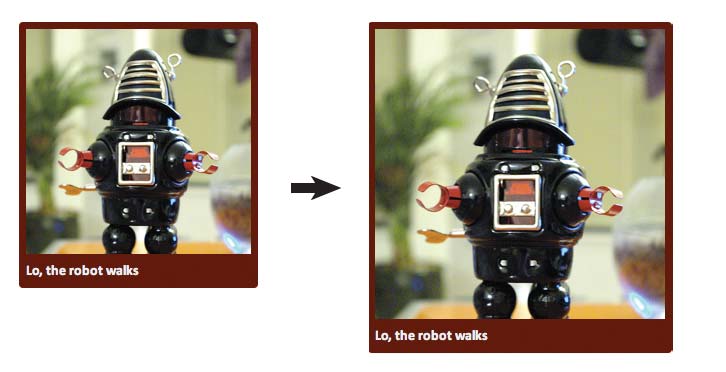

I hope you’re not tired of all this good news because as it happens,

the max-width: 100% rule can also apply to most fixed-width

elements, like video and other rich media. In fact, we can beef up our

selector to cover other media-ready elements, like so:

img,

embed,

object,

video {

max-width: 100%;

}

Whether it’s a cute little Flash video

(FIG 3.5), some other embedded media, or

a humble img, browsers do a fair job of resizing the content

proportionally in a flexible layout. All thanks to our lightweight

max-width constraint.

FIG 3.5: Other

media play nicely with max-width: 100%,

becoming flexible themselves. Did I mention I love max-width: 100%?

So we’ve cracked the problem of flexible images and media—right? One CSS rule and we’re done?

Because this job is never easy

Time to let the healing begin: we need to work through the pain, the tears, the rending of garments, and talk about a few browser-specific issues around flexible images.

max-width in Internet Explorer

The cold, hard truth is that Internet Explorer 6

and below don’t support the max-width property.

IE7 version and above? Oh, it is positively brimming with

support for max-width. But if you’re stuck supporting the

(cough) venerable IE6 or lower, our approach needs

refinement.

Now, there are several documented ways to get max-width

support working in IE6. Most are JavaScript-driven, usually relying on

Microsoft’s proprietary expression filter to dynamically

evaluate the width of an element, and to manually resize it if it exceeds a

certain threshold. For an example of these decidedly non-standard

workarounds, I’d recommend Svend Tofte’s classic blog entry on the

subject (http://bkaprt.com/rwd/12/).

Me? I tend to favor a more lo-fi, CSS-driven approach. Namely, all modern browsers get our max-width constraint:

img,

embed,

object,

video {

max-width: 100%;

}

But in a separate IE6-specific stylesheet, I’ll include the following:

img,

embed,

object,

video {

width: 100%;

}

See the difference? IE6 and lower get

width: 100%, rather than the max-width: 100%

rule.

A word of warning: tread carefully here, for these are drastically

different rules. Whereas max-width: 100% instructs our images

to never exceed the width of their containers, width: 100%

forces our images to always match the width of their containing

elements.

Most of the time, this approach will work just fine. For example, it’s

safe to assume that our oversized robot.jpg image will always

be larger than its containing element, so the width: 100% rule

works beautifully.

But for smaller images like thumbnails, or most embedded movies, it might not be appropriate to blindly up-scale them with CSS. If that’s the case, then a bit more specificity might be warranted for IE:

img.full,

object.full,

.main img,

.main object {

width: 100%;

}

If you don’t want the width: 100%

rule to apply to every piece of fixed-width media in your page, we

can simply write a list of selectors that target certain kinds of images or

video (img.full), or certain areas of your document where

you know you’ll be dealing with oversized media (.main img

, .main object). Think of this like a whitelist: if images or

other media appear on this list, then they’ll be flexible; otherwise,

they’ll be fixed in their stodgy old pixel-y ways.

So if you’re still supporting legacy versions of Internet Explorer, a

carefully applied width: 100% rule can get those flexible

images working beautifully. But with that bug sorted, we’ve still got one

to go.

And boy, it’s a doozy.

In which it becomes clear that Windows hates us

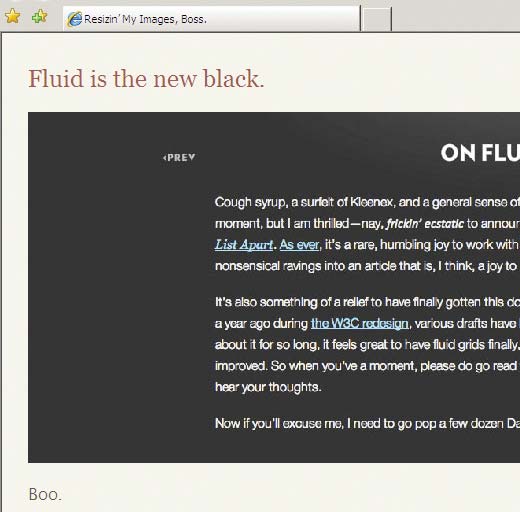

If you look at our blog module with certain

Windows-based browsers, our robot.jpg has gone from looking

imposing to looking, well, broken (FIG 3.6).

But this isn’t a browser-specific issue as much as a

platform-specific one: Windows doesn’t scale images that well. In fact,

when they’re resized via CSS, images quickly develop artifacts on

Windows, dramatically impacting their quality. And not in a good way.

FIG 3.6: Seen here in IE6, our robot image has developed some unsightly artifacts. Guess Windows doesn’t much care for our flexible images.

For a quick test case, I’ve tossed a text-heavy graphic into a

flexible container, and then resized our image with the max-width:

100% fix, while IE6 and below receive the width: 100%

workaround. Now, you’d never actually put this amount of text in

an image. But it perfectly illustrates just how badly things can get in IE7 or lower.

As you can see, the image looks—if you’ll pardon the

technical term—downright nasty (FIG 3.7).

FIG 3.7: In certain Windows-based browsers, the image quickly develops too many artifacts to be readable.

But before you give up on the promise of scaleable, flexible images, it’s worth noting that this bug doesn’t affect every Windows-based browser. In fact, only Internet Explorer 7 and lower are affected, as is Firefox 2 and lower on Windows. More modern browsers like Safari, Firefox 3+, and IE8+ don’t exhibit a single problem with flexible images. What’s more, the bug seems to have been fixed in Windows 7, so that’s more good news.

So with the scope of the problem defined, surely there’s a patch we can apply? Thankfully, there is—with the exception of Firefox 2.

Now, this grizzled old browser was released in 2006, so I think it’s safe to assume it isn’t exactly clogging up your site’s traffic logs. At any rate, a patch for Firefox 2 would require some fairly involved browser-sniffing to target specific versions on a specific platform—and browser-sniffing is unreliable at best. But even if we did want to perform that kind of detection, these older versions of Firefox don’t have a switch that could fix our busted-looking images.

Internet Explorer, however, does have such a toggle. (Pardon me whilst I swallow my pride for this next section title.)

Hail AlphaImageLoader, the conquering hero

Ever tried to get transparent PNGs working in

IE6 and below? Chances are good you’ve encountered

AlphaImageLoader, one of Microsoft’s proprietary CSS filters

(http://bkaprt.com/rwd/13/). There

have since been more robust patches created for IE’s lack of support for

the PNG alpha channel (Drew Diller’s DD_belatedPNG library is a current

favorite of mine: http://bkaprt.com/rwd/14/), but

historically, if you had a PNG attached to an element’s background, you

could drop the following rule into an IE-specific stylesheet:

.logo {

background: none;

filter:

progid:DXImageTransform.Microsoft.AlphaImageLoader

(src="/path/to/logo.png",

sizingMethod="scale");

}

This AlphaImageLoader patch does a few things. First, it

removes the background image from the element, then inserts it into an

AlphaImageLoader object that sits “between” the proper

background layer and the element’s content. But the

sizingMethod property (http://bkaprt.com/rwd/15/) is the clever

bit, dictating whether the AlphaImageLoader object should

crop any parts of the image that overflow its container, treat

it like a regular image, or scale it to fit it

within its containing element.

I can hear you stifling your yawns by now: after all, what does an IE-specific PNG fix have to do with our broken image rendering?

Quite a bit, as it turns out. At one point I discovered that applying

AlphaImageLoader to an image dramatically improves

its rendering quality in IE, bringing it up to par with, well, every other

browser on the planet. Furthermore, by setting the

sizingMethod property to scale, we can use our

AlphaImageLoader object to create the illusion of a flexible

image.

So I whipped up some JavaScript to automate that process. Simply

download the script (available at http://bkaprt.com/rwd/16/) and include it

on any page with flexible images; it will scour your document to create a

series of flexible, high-quality AlphaImageLoader objects.

And with that fix applied, the difference in our rendered images is noticeable (FIG 3.8): in our example we’ve gone from an impossibly distorted image to an immaculately rendered one. And it works wonderfully in a flexible context.

FIG 3.8: Our image is now

perfectly legible, and resizing wonderfully. A dab of AlphaImageLoader’ll do ya.

(It’s worth mentioning that many of Microsoft’s proprietary filters,

and AlphaImageLoader in particular, have some performance

overhead associated with them—Stoyan Stefanov covers the pitfalls in

more detail on the YUI blog: http://bkaprt.com/rwd/17/. What does this

mean for you? Just be sure to test the fix thoroughly on your site, gauge

its effect on your users, and evaluate whether or not the improved

rendering is worth the performance tradeoff.)

With the max-width: 100% fix in place (and aided by our

width: 100% and AlphaImageLoader patches), our

inset image is resizing beautifully across our target browsers. No matter

the size of the browser window, our image scales harmoniously along with

the proportions of our flexible grid.

But what about images that aren’t actually in our markup?

Flexibly tiled background images

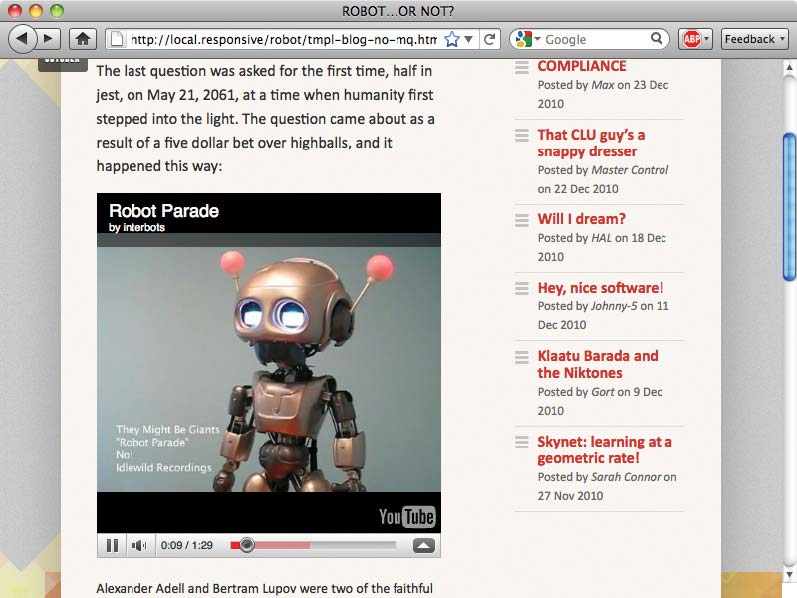

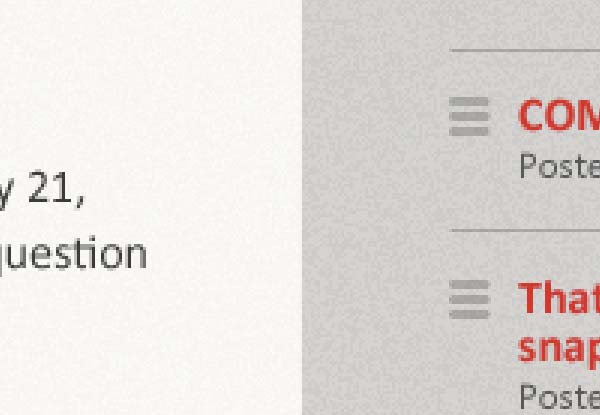

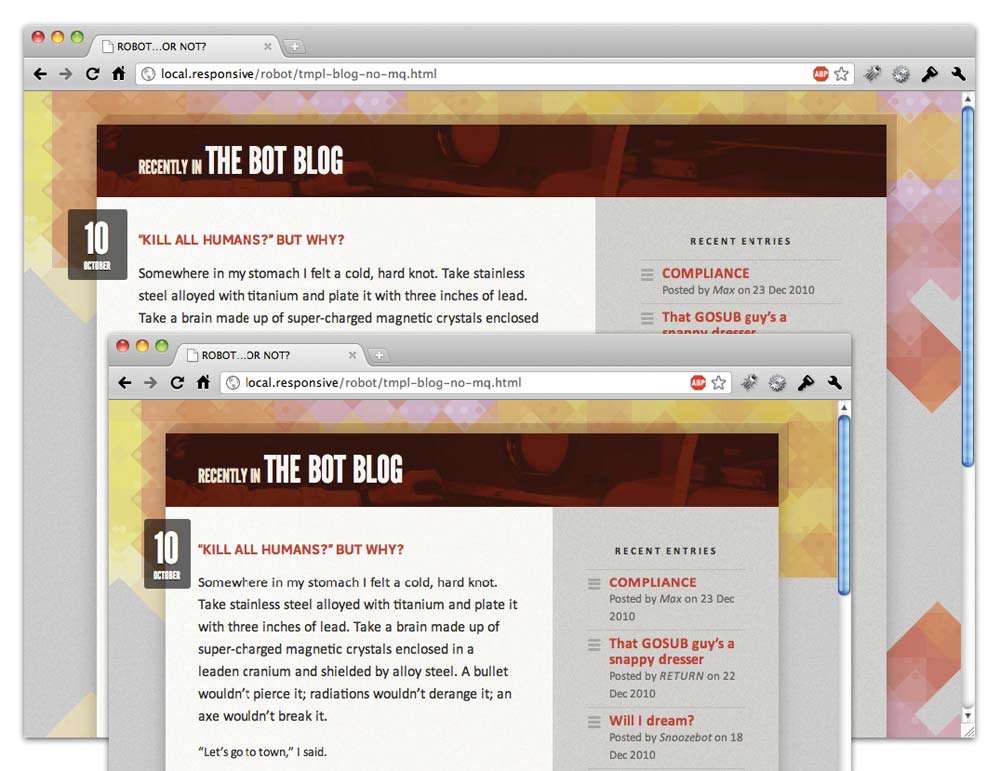

Let’s say our dearly esteemed designer sends over a revised mockup of our blog module. Notice anything different about it? (FIG 3.9)

FIG 3.9: Our blog’s sidebar is now sporting a background graphic. Hot.

Up until now, our blog’s content has been sitting on a rather unassuming near-white background. But now the design has been modified slightly, adding a two-toned background to the blog entry to provide more contrast between the left- and right-hand columns. What’s more, there’s actually a subtle level of noise added to the background, adding an extra level of texture to our design (FIG 3.10).

FIG 3.10: A detailed look at our new background treatment.

So: how do we actually add this new background image to our template?

Back in 2004, Dan Cederholm wrote a brilliant article showing how a vertically repeating background graphic could be used to create a “faux column” effect (http://bkaprt.com/rwd/18/). The technique’s genius is in its simplicity: by tiling a colored background graphic vertically behind our content, we can create the illusion of equal height columns.

In Dan’s original technique, the background graphic was simply centered at the top of the content area and then tiled vertically, like so:

.blog {

background: #F8F5F2 url("blog-bg.png") repeat-y 50% 0;

}

And that technique works beautifully. But Dan’s technique assumes that your design is a fixed width, creating a graphic that matches the width of your design. Then how, pray, are we supposed to work in a background image that tiles over two flexible columns?

Thanks to some early research by designer Doug Bowman (http://bkaprt.com/rwd/19/), we can still

apply the faux column technique. It just requires a little bit of extra

planning, as well as a dash of your favorite formula, target ÷

context = result.

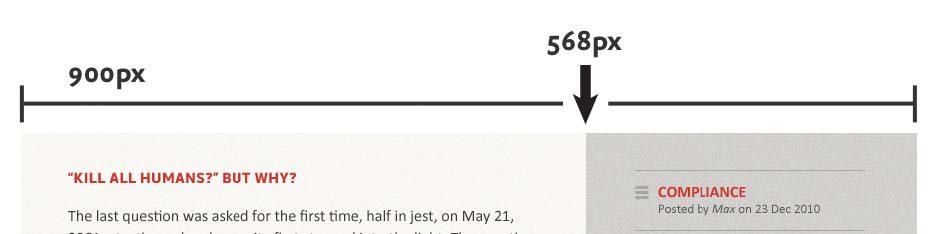

First, we’ll begin by taking a look at our mockup, to find the transition point in our background graphic, the exact pixel at which our white column transitions into the gray. And from the look of things, that switch happens at the 568 pixel mark (FIG 3.11).

FIG 3.11: Our white

column switches over to gray at the 568px

mark. That’s our transition point.

Armed with that information, we can now adapt the “faux columns”

approach to our fluid grid. First, we’ll convert that transition point

into a percentage-based value relative to our blog module’s width. And to

do so, our target ÷ context = result formula comes into play

yet again. We have our target value of 568px, and

the width of the design—our context—is 900px.

And if we plug those two values into our stalwart formula:

568 ÷ 900 = 0.631111111111111

That’s right: another impossibly long number,

which converts to a percentage of 63.1111111111111%.

Keep that percentage in the back of your mind for a moment. Now, let’s

open up your favorite image editor, and create a foolishly wide

document—say, one that’s 3000 pixels across (FIG 3.12). And since we’re going to tile this

image vertically, its height is only 160px tall.

FIG 3.12: A monstrously large canvas that we’ll (shortly) turn into our background graphic.

In a moment, we’re going to turn this blank document into our background graphic. But why is it so large? Well, this image needs to be larger than we can reasonably assume the browser window will ever be. And unless you’re reading this from the 25th century on your wall-sized display made of, I don’t know, holograms or whatever, I’m assuming your monitor’s not quite that wide.

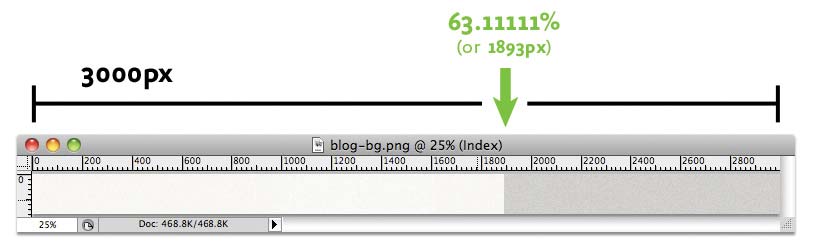

To create the columns themselves, we’ll need to apply the transition

point percentage (63.1111111111111%) to our new, wider

canvas. So if we’re working with a graphic that’s 3000px across, we

simply need to multiply that width by the percentage, like so:

3000 x 0.631111111111111 = 1893.333333333333

We’re left with 1893.333333333333 as our result. And

since Photoshop doesn’t deal in anything less than whole pixels, let’s

round that down to 1893 pixels. Armed with that number, we’ll recreate

our textures in our blank image, switching from white to gray at the 1893rd

pixel (FIG 3.13).

FIG 3.13: We’ve applied that percentage to our oh-so-wide background graphic, creating our tile-ready columns.

How does that help us? Well, what we’ve just done is to proportionally

scale our transition point up to this new, wider canvas. So we can

take that new pixel value, and use it to create our columns: the white

column will be 1893px wide, with the gray column filling up

the remainder.

So now there’s only one thing left to do: drop our newly minted graphic into our stylesheet.

.blog {

background: #F8F5F2 url("blog-bg.png") repeat-y 63.1111111111111% 0; /* 568px / 900px */

}

As in Dan’s original technique, we’re still

positioning the graphic at the very top of our blog, and then repeating it

vertically down the width of the module (repeat-y). But the

background-position value reuses our transition point

percentage (63.1111111111111% 0), keeping the columns

firmly in place as our design resizes itself.

And with that, we’ve got faux columns working beautifully in a fluid layout (FIG 3.14). All thanks to Dan Cederholm’s original approach, augmented with a little proportional thinking.

FIG 3.14: Our flexibly faux columns.

Fully flexible background images?

Of course, our flexible faux column isn’t really flexible: we’re simply using percentages to position a background image in such a way that the columns appear to resize with their container. The image’s dimensions haven’t changed at all.

But what about a background image that actually does need to resize with

the layout? Perhaps you’ve placed a logo on an h1

element’s background, or used sprites to create rollovers for your

site’s navigation. Can we resize images that need to live in the

background?

Well, sort of. There is a CSS3 property called

background-size (http://bkaprt.com/rwd/20/), which would

allow us to create truly flexible background images, but—you guessed

it—browser support is still pretty immature.

In the interim, there are some rather ingenious JavaScript-based

solutions out there: for example, Scott Robbin’s jQuery Backstretch

plugin (http://bkaprt.com/rwd/21/)

simulates resizable background images on the body element. And as

you’ll see in the next chapter, CSS3 media queries could also be used to

apply different background images tailored to different resolution ranges.

So while background-size might not be available yet, the sky

is, as the kids say, the limit.

Learning to love overflow

There are a few other options for working fixed-width images into a fluid context. In fact, you might consider browsing through Richard Rutter’s experiments with wide images placed in flexible layouts (http://bkaprt.com/rwd/11/). There are a number of promising experiments listed there, some of which might prove useful to you as you start tinkering with flexible layouts.

One method I’ve used on a few occasions is the overflow

property. As we saw earlier in the chapter, wide images will, by default,

simply bleed out of their containing elements. And in most cases, the

max-width: 100% rule is the best way to constrain them,

snapping them back down to a manageable size. But alternately, you could

simply clip off that excess image data by applying overflow:

hidden. So rather than setting our inset image to resize itself

automatically:

.feature img {

max-width: 100%;

}

We could instead simply clip off all that excess, overflowing data like so:

.feature {

overflow: hidden;

}

.feature img {

display: block;

max-width: auto;

}

And there you have it: one image, cropped to fit inside its container (FIG 3.15). The image is all still there, but the excess bits have just been hidden from view.

FIG 3.15: And with a dash

of overflow: hidden applied to our

image’s container, we’re left with an image that’s . . . well,

cropped. Yay, I guess?

Now, as you can see, this isn’t really a workable solution.

In fact, I’ve found that in the overwhelming majority of cases,

overflow is generally less useful than scaling the image via

max-width. But still, it’s an option to be considered, and

one you might find some use for.

Negotiate that content

It’s worth noting that both the

overflow and max-width: 100% approaches to

flexible images are actually pretty robust, and work remarkably well for

most kinds of media. In fact, I’ve used them successfully on a number of

complex fluid grids.

However, both approaches are ultimately “content-blind.” Each

establishes some basic rules for the way an image interacts with its

container: max-width: 100% scales oversized images down to

match the width of their containers, while controlling

overflow allows the designer to conceal any image data that

might bleed out of its containing element.

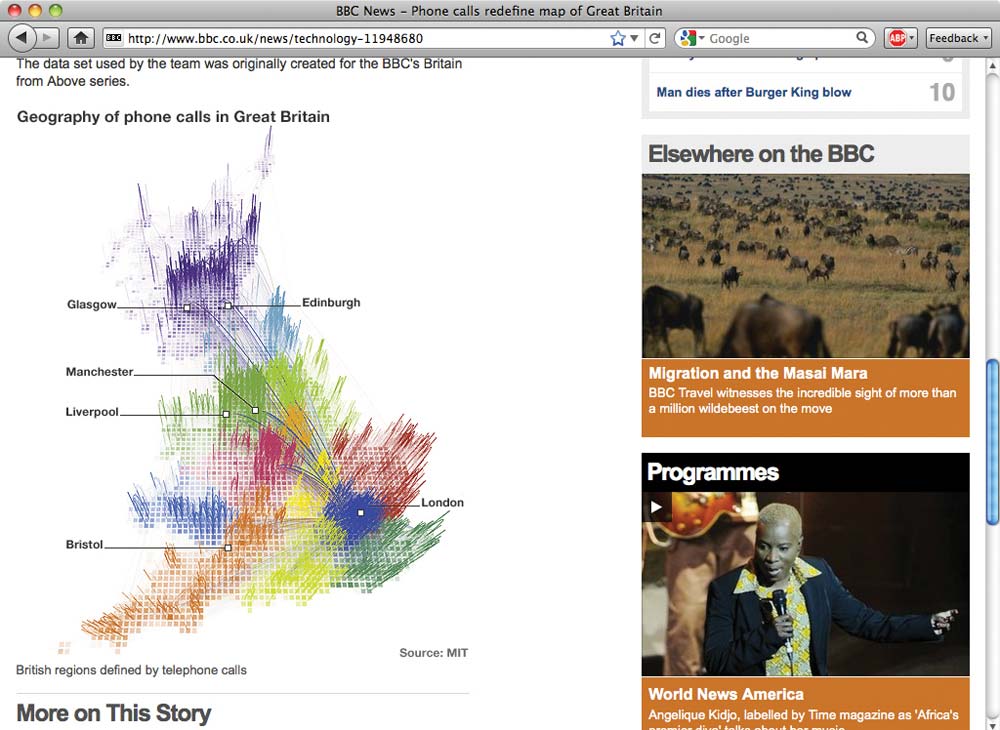

But what about especially complex graphics? If your image is especially information-rich (FIG 3.16), simply scaling or cropping it might be less than desirable—in fact, those approaches might actually impede your readers’ ability to understand the content contained in that image.

FIG 3.16: This rich infographic from the BBC News site (http://bkaprt.com/rwd/22/) contains information critical to the page’s content. Simply scaling it down could prove counterproductive.

If that’s the case, it might be worth investigating ways of delivering different versions of the same image to different resolution ranges. In other words, you could create multiple versions of your infographic—say, one ideal for desktop browsers, as well as another, more linearized version for small-screen devices. With those options established, a server-side solution could intelligently serve the most appropriate image for that resolution range.

Creating such a solution is beyond the scope of this book (and beyond the skill of your humble author), but designer/developer Bryan Rieger has outlined one possible approach on his blog (http://bkaprt.com/rwd/23/), and made his solution available for download.

If you decide to implement a back-end solution, it could be augmented by

the various client-side techniques we’ve discussed so far. For example,

you could serve images to a limited number of resolutions, and then use

max-width: 100% to smooth the transition to other devices,

browsers, and resolution ranges on an as-needed basis.

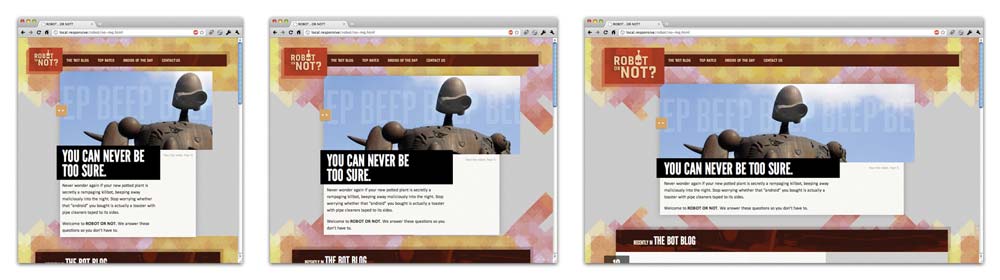

Flexible grids and images, up in the proverbial tree

At this point, we’ve explored everything you need to build complex but flexible grid-based layouts: the simple math behind flexible grids and some strategies for working images and other media into that framework. While we’ve been focusing on building a fairly simple blog module, we can actually use this to build the rest of the Robot or Not site, creating a design that’s founded on a system of proportions and percentages, with nary a pixel in sight (FIG 3.17).

FIG 3.17: Two chapters later, and we’ve finally got a completed grid-based layout that can expand and contract with a changing viewport.

With this flexible foundation in place, we’re ready to add the final ingredient to our responsive design.

(And no, it’s not mixed metaphors.)