1. Great Expectations

Man Walks into a Bank...

For millions of Baby Boomers preparing for retirement, we live in an era of what can best be described as Romantic Illogic. Consider the curious case of Timothy J. Bowers. In Columbus, Ohio, Mr. Bowers, age 62, couldn’t find work, so he came up with a plan to make it through the next few years until he could collect Social Security. Mr. Bower’s plan was out of the ordinary, to say the least. He robbed a bank and then handed the money over to a guard and waited for the police. Mr. Bowers passed a court-ordered psychological exam, and got his wish...he was sentenced to three years in prison, just enough time to take him to his Golden Years when he could collect his full Social Security check. The prosecutor was quoted as saying, “It’s not the financial plan I would have chosen, but at least it was a plan.”1

Before the Meltdown of 2008, very few Boomers had a retirement plan, but millions had retirement expectations. For example, 59% of the people in a survey said they expected to receive a pension check; however, only 41% knew of a pension to which they or their spouse were entitled.2 Of the people who actually had a pension coming, the median expected annual pension was $20,000, but the median actual pension payout was only $8,340.3 So did the bull market and strong economy create a quixotic-like disconnect between reality and fantasy? Why else would 50% of American workers say they expected to retire at 62, and 80% believed their standard of living would go up in retirement?4 Why else would 70% of Boomers expect to leave an inheritance, not knowing if there was really any money to be left to their heirs?5 After the Meltdown of 2008, you have to wonder: Who exhibited more irrational behavior...the bank-robbing Mr. Bowers who had a plan or the overconfident Boomer who had an expectation?

The New McFear

When some of the world’s largest companies and banks essentially vaporize or are forced to sell themselves in a matter of months, and the global economy appears to be sinking with record speed and harmony,6 even the worst-conceived plans and the best-laid expectations can turn to fear, and suddenly no fear, for some of us, may seem irrational. In October 2008, Alan Greenspan, the former chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve, confessed to Congress that he was “shocked” when the markets did not operate according to his lifelong expectations.7 When things are tight and negative, economic news fills the headlines; people may tend to hold back on spending, pull money out of long-term investments, and potentially exacerbate the problem by holding onto their nest eggs for dear life. During the Meltdown of 2008, Bill Gross, considered the nation’s most prominent bond investor, hypothetically equated the squeezed credit markets to being like a trip to a McDonald’s drive-thru where one would pay at the first window, but could not be sure of actually getting their food at the second window. “They are frozen in ‘McFear,’” said Gross.8

In a crisis, no story in the media seems out of bounds, which is why the media stokes fear. Case in point, remember the Avian flu, better known as the bird flu? In 2005, it was reported that an outbreak of the bird flu could kill anywhere between 2 million and 150 million people, but as of this writing there have been only 263 reported deaths caused by this disease.9 Although the bird flu was indeed potentially dangerous, a measured, informative public discussion of the potential pandemic seemed nowhere to be found in the mass media. In the meantime, something much bigger was taking place, something that takes place every day, every month, every year in America, and yet it gets scant coverage as a rule. That something? The flu. That’s right, the average, ordinary flu that we’ve probably all had a touch of at one time or another. In a flu season in the United States, an average of 36,000 people die of the flu or flu complications, and about 200,000 people are hospitalized.10 That’s more than 98 fatalities a day and well over 500 hospitalizations a day if the flu season were spread out over a year. Fortunately, bird flu hasn’t come anywhere close to exacting that kind of toll, but as we all know, fear sells, and our perception of fear becomes reality.

As our economy suffered its own kind of flu, the headlines got worse and behavior became more irrational. After all, the economy is not only affected by the way people behave with their money, but it also affects the way people behave with their money. An example of this self-fulfilling prophecy is the hot dog stand story, which has been told in one form or another for well over 40 years. Here’s the tale: Once upon a time, there was a man who ran a hot dog stand. This man ran one of the finest hot dog stands in the whole city and, strangely enough, he even used real meat in his sausages. People came from miles around to get his tasty hot dogs that were generously covered in onions and sauces. In fact, the man was so successful that he could afford to send his son to an Ivy League school. After graduation, the prodigal son came back home to visit his pop and took a look at the family business. “Dad,” he said, “based on the current economic statistics, we’re heading for a recession. You should really stop using all that sauce, and you dish out onions as if they were free. And you’ve been talking about expansion—adding another hot dog stand. Not the time to do that, Dad,” he said. The father was torn. He was always generous to his customers, but his very bright son didn’t get all that education for nothing. So, reluctantly, the father cut back on the sauces and onions. He held off on his expansion plans. His son even convinced him to buy a cheaper brand of hot dog. Although the son meant well, the timing of these cutbacks turned out to be just right, because right then the father’s business took a real dive. After years of prospering as a street vendor, the hot dog man lost so many loyal customers to the competition, he had to close his stand. The moral of the story: The more you react to the fears and emotion of a recession, the more likely the recession will find you. Or...what was the son thinking and what was the father feeling?

The Retirement Brain Game

At the risk of oversimplifying how the brain works, this complex machine can be divided into two cognitive systems. As mentioned in the introduction, the automatic system is subjective, intuitive, and instinctive, whereas the reflective system is objective, rational, and more deliberate. The automatic system is popularly coined the “right brain,” whereas the reflective system is referred to as the “left brain.” You’ve probably heard people say that they are either right-brain thinkers or left-brain thinkers; schools even build whole-brained curriculums to give equal weight to both sides of the way our brain functions. In the story you just read, the hot dog vendor approached his business with blind emotion, but his son actually evaluated the situation with what could be described as blind logic; both emotion and miscalculation can cloud our financial decision making. Although the right side of the brain is the culprit for most of our financial mistakes, the two sides together are often at odds, resulting in fear, dread, anxiety, euphoria, sadness, and conflict—essentially everything that makes us human. And because we are all human, let’s have a little fun. Imagine the two sides of a Boomer’s brain having a conversation. What might they say about retirement?

This is your brain. This is your brain on retirement.

Right Brain: Whoo hoo! Can’t wait to retire.

Left Brain: Retire? What exactly is the plan?

Right Brain: Travel. Beach. Golf. But not just for two weeks, for the rest of my life.

Left Brain: Okay, so tell me. Have you thought about the numbers?

Right Brain: 18—as in holes a day.

Left Brain: You are irrational.

Right Brain: I am exuberant.

Left Brain: Seriously.

Right Brain: Okay, we’ll sell the house.

Left Brain: Underwater. With three mortgages.

Right Brain: Investments?

Left Brain: Down 40% since the meltdown.

Right Brain: What about our nest egg?

Left Brain: I told you to start 25 years ago, Mr. Procrastinator.

Right Brain: We can always count on family.

Left Brain: Not returning calls.

Right Brain: Government?

Left Brain: Have you seen the news?

Right Brain: You’re freaking me out.

Left Brain: The technical term for that is ohnosis.

Expectations are driven by a number of behaviors, and from behavioral finance we examine a few concepts in this chapter, such as overconfidence and illusion of control, that helped shape high expectations for Boomers prior to the meltdown. I’ll review a familiar concept called procrastination and a not-so-familiar concept called the recency effect, both of which will most likely continue to influence, and even plague, investor behavior in the post-meltdown era.

Procrastination—Psychological bias that keeps people from engaging in the day-to-day activities that could result in a long-term benefit. One way it manifests itself is the way people fail to sign up for their 401(k) accounts when they become eligible, which is often months after starting with a company. They become comfortable with their take-home pay and don’t believe they can cut into it at all to fund a retirement that’s decades away. So they put off funding their retirement, spend all their pay, and do nothing to maximize their wealth.

Overconfidence—Actions based on an exaggerated estimation of one’s knowledge, skill, and good fortune. Even if a person did nothing to make that investment successful, other than buy it, he may think that he’s learned something important about how to make money in the market and try to apply that learning to future investments. The result is that the investor believes he knows more than he actually does and can control more than he actually can.

Illusion of Control—The tendency for investors to believe that they can control or influence an outcome over which they have absolutely no control.

Recency Effect—Giving more importance to recent events than to those events that took place further in the past. Investors who were recently stung by the market, as was the case in the fall of 2008, were cautious about getting back in during the bull market that took place in the spring and summer of 2009.

The Procrastinator’s Plight

Procrastination

The word conjures up images of laziness and detachment. And procrastination is a big reason why retirement expectations are not met. Procrastination isn’t necessarily a problem relegated solely to the unmotivated among us. It is a psychological bias that affects millions and can keep us from building a retirement nest egg. We all want to make timely, well-thought-out financial decisions, but procrastination lurks in the shadows waiting to derail our retirement dream.

Consider for a moment our increasingly complicated, ever-changing, fast-paced world. It is one that differs dramatically from the society we inherited from our parents and grandparents. Despite this radical technological evolution, our natural tendency is to keep things the way they were. And it’s an understandable reaction considering the blitz of changes constantly demanding our attention. After all, it’s much easier to do nothing rather than alter one more detail in our already busy and overburdened lives. In fact, Seinfeld, one of the most successful situation comedies of all time, was a self-proclaimed show about doing nothing. Truth is, most of us prefer to do nothing. For example, your car may no longer be exactly what you want, but keeping it is easier than looking for a new one. Do nothing. Your job may not be as satisfying as you would like, but the daunting task of searching for a new one may be even less appealing. Do nothing. Fifty-three percent of workers in the U.S. have less than $25,000 in savings and investments,11 but what will most of them do differently going forward? Nothing.

Many people acknowledge that procrastination plays a major role in keeping them from starting to plan for retirement. Why? You may be overwhelmed by the notion of retirement; afraid you’ll make too many mistakes in retirement planning; have too many competing priorities; or just lack a sense of urgency. According to a survey conducted on behalf of the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, the majority of adults would choose to receive financial advice over the advice of a personal trainer, interior designer, or fashion consultant, if given the opportunity.12 But here’s the conundrum: LIMRA, a financial services research firm, reports only 15% of consumers said they had consulted with an adviser during the economic crisis. Whereas 85% procrastinated and did nothing, even during a crisis, two-thirds of those investors who did seek financial advice during the crisis felt reassured and were glad they acted.13

The Cost of Waiting

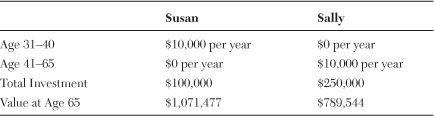

A consistent theme among our age 60+ focus group participants was regret over not starting to plan for retirement sooner. Although better late than never is always a worthwhile notion, urging your children to start planning for their financial future as early as possible is one of the most important pieces of advice you can pass along to your family. Let’s take a look at the advantage of starting early and the disadvantage of procrastinating. Table 1.1 illustrates the potential cost of waiting to invest. Susan invests $10,000 for 10 years and stops. Sally waits 10 years and then invests $10,000 for 25 years. Assuming a hypothetical rate of return of 8% for both, Susan will have more money than Sally despite investing significantly less money upfront.

Table 1.1 SUSAN VERSUS SALLY: The Power of Time (Hypothetical Example)

This chart is hypothetical and for illustrative purposes only. The hypothetical rates of return shown in this chart are not guaranteed and should not be viewed as indicative of the past or future performance of any particular investment. This chart assumes a hypothetical rate of return of 8%.

Think about it. Have you ever heard people say they were glad that they waited years, even decades, to begin planning for their retirement? Many people acknowledge that procrastination plays a major role in keeping them from doing a better job of planning for their retirement. There are so many choices and unknowns that it is often easier to focus on the more immediate concerns of daily living.

“What I have on the list, I think my biggest obstacle is me, quite honestly. I just feel kind of overwhelmed by the topic. There is almost so much information about ways to prepare and invest in retirement, that to me it overwhelms me and I shut down. It’s always I’ll look another day, I’ll check into that tomorrow. I have no doubt that I am my biggest obstacle to achieving great success in retirement.”

—Male Focus Group Participant

Some investors take the opposite approach. Rather than proscrastinate, they invest immediately, without making more patient choices for the future. For example, someone offered the choice between receiving $100 today or $110 tomorrow might be tempted to take the money today. But if that same person were asked to choose between receiving $100 a year from now, or receiving $110 in a year and one day, he would likely prefer to wait the extra day for the larger payoff.14 Instant gratification can also be a factor in the behavior of procrastination; in some cases, people will do what is necessary to get something they want immediately but are not inclined to start acting on something that may get them what they’re after 20–30 years down the road. Behavioral finance studies have been conducted with fruit and chocolate, as well as “low brow” and “high brow” movies.15 In both studies, people will typically choose chocolate and “low brow” movies today, and fruit and “high brow” movies tomorrow.16 When it comes to retirement planning, making impatient choices and opting for instant gratification today, while delaying patient, even better and better-for-you choices for tomorrow can affect our investment decisions. For example, rather than being patient and riding out paper losses from investment downturns, people may act without thinking and make investment decisions that aren’t prudent.

Failure to follow through once a decision has been reached is also a common factor in procrastination. And it’s an easy one to relate to. Take joining a gym, for example. When buying gym memberships, I think many people tend to be overeager and possibly naïve in their forecasting. A discounted monthly payment may seem like a smarter move than a higher per visit fee, but if you don’t show up, the per-visit fee is a better value. I had a friend with a very busy schedule who was excited about joining 24-Hour Fitness® because he could go anytime—even in the middle of the night to work out. “Problem is,” he said, “I never got the urge to go to the gym in the middle of the night—so I never got to the gym.” But he kept making his so-called discounted monthly payment, which was pulled directly from his checking account.

We live in a busy world that’s constantly pulling us in different directions. There’s no question that most people want to take actions that will benefit their financial bottom line, but they often do not finish the task. When faced with making an important or complex decision, it’s not unusual for investors to either keep things the way they are or delay making a decision until later. This behavior is particularly damaging to retirement and can be seen in the way many workers fail to take advantage of company-sponsored retirement plans. Despite easy access to investment information, many employees have difficulty taking action even though they understand the need to join their retirement plan, choose allocations, and increase their contribution rates.

The Overconfident Investor

Although procrastination traps us in the gap between thinking and doing, overconfidence tricks us into thinking we are better than we actually are at performing a particular task. Investors who suffer from overconfidence have a tendency to believe that their forecasts are right and that more knowledge will only solidify their beliefs. But the fact is that more knowledge can sometimes be contradictory to what an investor already knows. Although common sense dictates that learning more about an investment would naturally make a person a better investor, a behavioral finance concept called the illusion of control dictates that’s not necessarily the case.

Rooted in overconfidence, the illusion of control tricks people into thinking they have more control over an outcome than they actually do. An example is the documented fact that if you ask someone to bet on which side a coin will land on, the person will bet more money on the side it didn’t land on the time before. The problem with this thinking is that the coin obviously has two sides, and there’s a 50% chance a tossed coin will land on one side each time the coin is flipped. Like the coin toss, investors frequently use last year’s result to make this year’s investment decisions without properly analyzing the information. Our minds are calibrated to believe only what we will accept, and we are often surprised when predictions prove not to be right. We know the past, especially the recent past, like a stock’s year-to-date earnings, but there’s so much more to know to make an educated investment decision. Based on what we do know, many of us have a tendency to believe that we have more control over an outcome than we really do. Witness the all-star baseball player who has a superstition of tapping his spikes before entering the batter’s box. He may claim that such a ritual helps him succeed, but if he has a .300 batting average, that means he does not succeed 70% of the time. Although such an average is quite impressive in baseball, the batter’s ability and mastery of his skill have a lot more to do with his success than the superstition that gives him the illusion of control.

Are you overconfident?

Before we continue, answer this question: How would you rate your driving skill? Compared to other drivers you encounter on the road, are you

• Above average

• Average

• Below average

If you’re like most people, you answered that you are above average. When we asked our focus group participants this question, 90% of the room stated they were above average, but given that our focus group was composed of a cross section of America, it is very unlikely that 90% of the room was average or above. Just like driving, many Americans may be overconfident that their investment decisions are prudent. For example, during the bull market, some investors thought they knew best where to put their money, and they continue to think that to this day. In the ’90s, they believed it was tech stocks; in the late 2000s, it seems to have been target date funds and home equity. CNBC’s two-part special House of Cards, which aired in January of 2009 and detailed the financial meltdown that was triggered by the bursting of the real estate bubble, featured an interview with Alan Greenspan. During the interview, Greenspan stated that all the people who’d invested heavily in real estate or subprime mortgage-backed securities thought they would get out of those positions ahead of everyone else. But many of these people—among them some of the brightest minds on Wall Street—did not get out ahead of the others and, in fact, they were holding worthless paper when the meltdown happened.

The Nearsighted Investor

Overconfidence in both bull and bear markets can, in part, be attributed to a behavioral finance concept known as the recency effect. When people look back over a short period of time, they remember the good things as well as the struggles. In investing terms, if a person looks back a quarter or two and sees his accounts have grown in value, he’s likely to invest even more, overloading investments in equities without maintaining a well-balanced portfolio. Conversely, when investors experience something like the Meltdown of 2008, they may react to it in the exact opposite way, perhaps being overly conservative with their investments. If we do not experience anything like the meltdown in the next year or so, investors will be less influenced by it. The recency effect dictates that experiences happening in real time affect behavior in real time, like an economic boom. Witness the American economy since the Baby Boomers came along: For the most part, the American economy and quality of life have risen consistently. After the meltdown, the relatively carefree days of the Dow at 14,000 (that happened just 50 weeks earlier) suddenly seemed like a distant memory. A new reality was upon Americans, and they reacted by looking at their finances in a whole new way. But how many react by permanently looking at their finances in a whole new way? “We will see people pulling in their belts for 1 or 2 years,” insists Augustana College history professor and American consumer credit expert Lendol Calder. “And then it will be back to where we left off.”17

When people are faced with a new reality, like losing their nest egg very quickly, they don’t always react as rationally as they should. Long-term knowledge and even experience is tossed out the window in favor of a reaction to short-term stimulus. The result is that businesses and individuals alike are doing what they can to cut back on expenses and even hoard money. At some point the headlines will stop trumpeting bad economic news, regardless of how good or bad the economy is at that point. At that time the hurt and anguish that was brought about by the meltdown will recede, and people will become more engaged about who’s the next American Idol than what they do with their dollars.

Improve Your Retirementology IQ

A century and a half ago, Charles Dickens wrote Great Expectations, about a young man named Pip who took the occasion of sudden wealth to eschew his working class roots and move up in London society. Like the mysterious benefactor who eventually bestowed riches upon Pip, many people expect to have their own retirement dreams fulfilled by other mysterious benefactors in the form of pension checks, lottery tickets, and rich uncles—great expectations of travel, leisure, devoting time and money to a charitable cause, winter homes and summer homes, time with friends and family, and possibly leaving a noble amount of money behind for those who are most important. In fact, when asked what is the most practical manner to accumulate $500,000 for retirement, 27% of respondents said winning the lottery or sweepstakes.18 Could it be that the survey was taken among characters in Dickens’ novel?

A meltdown has a way of changing expectations—even for a generation high on promise and light on planning.

Take a moment to evaluate what you’re thinking in this post-meltdown era. How well did you deal with your fears? Did you lose sleep? Did you develop a nervous tick? Did you watch the markets every day? Did you make any financial moves out of panic? It’s likely that a lot of the things you did do in response to the economic downturn you did because you didn’t know what else to do. Modifying your expectations doesn’t have to mean abandoning your retirement dreams—just rethinking them. Here are two takeaways to consider to get started on rethinking expectations.

Conduct a Personal Retirement Assessment

What do you want? What do you need? What are you willing to do, to sacrifice, to achieve these material things? You have to be willing to think about opportunity costs, like if you’ll be happy driving a less flashy car today to drive a golf cart every day in retirement. Or if you’re okay raising your family in your present house so that you might have a winter house in retirement. Some people simply can’t get past immediate gratification, whereas others look at all the issues and realize that they can put some things off now for the possibility of a secure retirement. Remember, even small decisions can make a big difference in your retirement planning, and retirement is ultimately affected by many monetary decisions throughout your life, like starting to plan ahead as early as possible.

Reevaluate Retirement Expectations

What’s your retirement dream? Would you like to retire to a big house overlooking a lake and the mountains where the view is always beautiful and you can decide whether you want to golf, ski, or go sailing every morning when you wake up? Everyone’s dream is unique, but reality can get in the way of a dream, even for the wealthiest retiree. What do you really want? And what will it take to get there? If it’s a winter house in Arizona or Florida, you have to know approximately how much it will cost. If it’s a boat so that you can travel the world, you need to have an idea of how much you’ll need. Be realistic. Be honest with yourself. Be as objective as you can be, and leave nothing out when you make your checklist...right down to how many golf balls you’ll need because you always hook your driver into the water. Improving your Retirementology IQ often begins by examining your options and feelings before the unthinkable happens. You may feel like the unthinkable has already happened. Keep in mind that, historically, the economy and markets have been cyclical. Learn from today, but don’t lose your long-term retirement perspective.

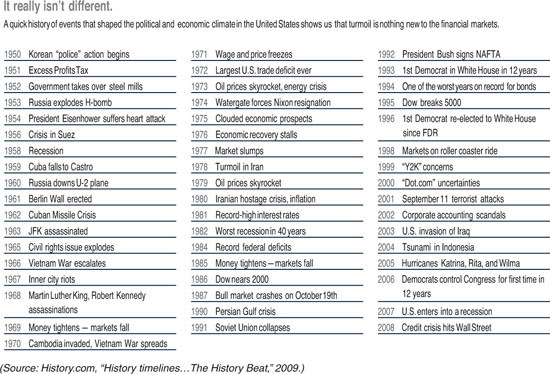

“This time it’s different”—perhaps four of the most dangerous words in investing. No matter what the political or economic climate may be like, investing always involves risks. Consider the growth of the S&P 500 Index since 1926 (see Figure 1.1). Like many investments, stocks have experienced some severe declines, as well as dramatic growth—despite wars and meltdowns. What will the next headline be?

Figure 1.1 Is it really different this time?

Mark Twain said, “Climate is what we expect, weather is what we get.” When it comes to expectations, the best thing you can do is check them at the door and plan for all kinds of weather in retirement.

UNREALISTIC LIFESTYLE EXPECTATIONS MAKE A

HAPPY RETIREMENT IMPOSSIBLE.

(Chart created by Jackson National Life Distributors LLC using performance information provided by the S&P.)

Widely regarded as one of the best single gauges of the U.S. equities market, the S&P 500 Index is a market capitalization-weighted index of 500 stocks that are selected by Standard & Poor’s to represent a broad array of large companies in leading industries. This chart represents the growth of a hypothetical $1 invested in the S&P 500 from 1926–2008, during which time the Index experienced an average annual return of 9.62%. The S&P 500 is an unmanaged, broad-based index and is not available for direct investment. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Endnotes

1 The New York Times, “Just Asking to Be Caught, Thief Solves Joblessness,” October 13, 2006.

2 Consumer Reports, “Are You Ready to Retire?” October 2008.

3 Tiburon Strategic Advisors, “Consumer Wealth, Liquefaction, & the Retirement Income Challenge Research Report – Key Highlights,” February 29, 2008.

4 USA Today, “Boomers’ eagerness to retire could cost them,” January 13, 2008; MSN Money, “9 dumb moves to ruin your retirement,” October 22, 2007.

5 Gallup News Service, “Most Americans Don’t Expect to Receive an Inheritance,” August 27, 2007.

6 PBS, “Frontline: Inside the Meltdown,” February 17, 2009.

7 The Wall Street Journal, “Greenspan ‘Shocked’ to Find Flaw in Ideology,” October 23, 2008.

8 PIMCO Investment Outlook, “Nothing to Fear but McFear Itself,” October 2008.

9 ABC News, “How Many People Could Bird Flu Kill?” September 30, 2005; World Health Organization, Cumulative Number of Confirmed Human Cases of Avian Influenza A/(H5N1) Reported to WHO, December 21, 2009.

10 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Estimating Deaths from Seasonal Influenza in the United States,” September 4, 2009; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Seasonal Influenza – Associated Hospitalizations in the United States,” September 8, 2009.

11 Employee Benefit Research Institute, “The 2009 Retirement Confidence Survey: Economy Drives Confidence to Record Lows; Many Looking to Work Longer,” No. 328, April 2009.

12 Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association, “Survey: Most Crave Financial Advice Over Personal Trainer, Fashion Consultant,” October 3, 2007.

13 LIMRA, “Consumer Views on the Fall of 2008,” 2008.

14 McClure, Samuel M., David I. Laibson, George Loewenstein, and Jonathan D. Cohen, “Separate Neural Systems Value Immediate and Delayed Monetary Rewards,” October 15, 2004.

15 Read, Daniel, and Barbara van Leeuwen, “Predicting Hunger: The Effects of Appetite and Delay on Choice,” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Vol. 76, Issue 2, pgs. 189–205, November 1998.

16 Read, Daniel, George Loewenstein, and Roy F. Baumeister, Time and Decision: Economic and Psychological Perspectives on Intertemporal Choice, Russell Sage Foundation Publications, 2003.

17 The New York Times, “The Last Temptation of Plastic,” December 7, 2008.

18 MSN Money, “Why poor people win the lottery,” May 9, 2008.