2. Gold Dust on Sushi

When they were seemingly on top of the economic world during the 1980s, the Japanese would routinely sprinkle gold dust on their sushi. Gold leaf flakes were sometimes used instead of dry seaweed to wrap the rice,1 and amazingly, the world record for spending on a sushi roll comes in at $83,500, paid in Tokyo in January 1992.2 A recent Japanese film, “Bubble e Go! Time Machine wa Drum Shiki,” which roughly translates to “Back to the Bubble,” revisits some of the common behaviors of the 1980 boom showcasing the extravagant practice of drinking green tea and sake with gold leaf flakes.3 The fad extended to other types of cuisine, including omelets, curries, and ice cream. Not to be left out, a New York restaurant began serving $1,000 sushi rolls wrapped in edible gold leafs.4 Indeed, sushi trends were a pretty good barometer for what was going on with the rest of consumer spending.

After decades of spending on fine dining, bigger houses, luxurious cars, electronic gadgets, expensive clothing, and all sorts of other niceties, America’s Baby Boomers now have an embarrassment of riches when it comes to material goods, but very little cash. The solution was simple: credit. Americans had more material wealth than they’d ever had, in spite of the fact that they had little in the way of actual cash savings. They were seeing their homes and other investments balloon in paper value. Then, they were getting home equity loans to pay for renovations, kids’ college tuition, a dream vacation, or even a new car. No sooner had they spent that newly created home equity, than they discovered the house had appreciated yet another 10%—providing further appreciation.5

The home equity loan wasn’t the only easy credit, though. For years, they were bringing in the mail every day to find about a half-dozen credit card applications with teaser offers enticing them to move revolving balances to these cards. As of 2008, Americans held more than $850 billion in credit card debt; that’s four times the credit card debt Americans held as recently as 1990.6 The result has been a widespread case of musical credit cards among the consumers who did hold revolving debt. Thirty-five million of them make only the minimum payment each month or move their balances from one card to another with a low teaser rate that would balloon to something like prime plus 12% after a few months.7

“People have come to view credit as savings,” says Michelle Jones, vice president at the Consumer Credit Counseling Service of Greater Atlanta.8 Easy credit kept the cycle going, and rising home values kept Americans feeling rich. Their behavior, however, didn’t make them rich. Consumers often treated the simple act of throwing down a card as the only thing between them and whatever they wanted at a particular time. Lunch? Put it on the card. Plane ticket? On the card, please. Big screen television? That’s what the card is for, right? What some people never really learned was that the interest they were paying by rolling over that balance from month to month could make that $5 lunch cost $205 when it was finally paid off. The $205 plane ticket may cost $2,005, and the $2,005 big screen TV could cost...well, you get the idea.

Too many of us were putting money into someone else’s pocket at an alarming rate by spending much more on a product than it was worth. Think of a chess player who continually gives up a bishop or a rook to capture a pawn; he won’t be very successful in the long term. The result? In 2008, Americans carried $2.56 trillion in consumer debt—22% of that has been incurred just since 2000.9 The picture that’s painted by these facts is that Americans now must set aside 14.5% of their disposable income just to service their debt.10

By comparison to the federal government, however, American consumers are so frugal they could be called fiscally responsible. At the end of the government’s fiscal year on September 30, 2009, the feds are running an incredible $1.42 trillion budget deficit, which is triple what it was a year before11 and bigger than the entire national debt as recently as 1984.12 So how big is the national debt now? How does $12.3 trillion hit you?13 So how many of our tax dollars are going to have to go toward just servicing that debt?

Many Americans who live well are so deep in debt that their quality of life would drop significantly in just a few weeks if the paychecks stopped coming in. According to one national study, 50% of Americans say they’re only one month—two paychecks—away from not being able to meet their financial obligations.14 More than half of those people, 28% of the total respondents, couldn’t survive financially for more than two weeks if they were suddenly without their present regular income.15 And before you think this issue concerns only lower socio-economic Americans, think again. Twenty-nine percent of the “mass affluent,” earning more than $100,000 per year, wouldn’t be able to meet financial obligations a month after losing their jobs.16 So how did we get here? What’s behind the carpe diem spending mentality?

America’s Spending Boom

Before the meltdown, it didn’t matter as much if we were a paycheck away from disaster. In recent years, most people didn’t even realize they were flirting with disaster, or if they did, they looked the other way. Let’s take a glimpse at some of the extravagance that underscored America’s carpe diem spending mentality.

• Luxuries became everyday necessities.

– Overspending Boomers might regularly drop $5 or $10 a day on intakes of latté, cappuccino, espresso, mocha, macchiato, and a multitude of other beverages, as Starbucks sales grew and stock went above $30 a share at the high point in 2007.17 Not bad, considering Starbucks stock traded at about 70¢ per share in the summer of 1992.18 One of our focus group participants noted, “People go to Starbucks, put the card through, get a $5 drink and don’t know how much they spent.” Another stated, “I have a friend who goes to Starbucks, and it makes me cringe because he is in debt a lot. He has a $4,000 Starbucks bill. And he juggles his credit cards.”

– Big-screen television sales shot up 300–400% from 2006 to 2007, as unit sales for the LCD TV category were up 74%.19

– Nearly one-third of U.S. adults went boating in 2006. Sales of new boats nationwide were $15 billion in 2006, a record high.20

• No vehicle was too lavish, big, or brawny.

– One successful Hummer dealer spent $7.5 million on a new 34,000-square-foot showroom in a wealthy suburb of St. Louis and turned 60 acres into a rough-terrain track to test drive his Hummers. This dealership was selling 70 new Hummers a month—priced from $30,000 to $100,000.21 Stories and features about exotic cars were also prevalent in magazines, as witnessed in a December 2005 Forbes magazine article that spotlighted such exotic cars as the $1.2 million Veyron 16.4, the $654,000 SSC Ultimate Aero, and the $285,000 Lambourghini Murciélago. Would any of those make a great holiday gift?

• No party was too lavish.

– Dozens of overprivileged kids had their coming-of-age extravaganzas captured on MTV’s hit series “My Super Sweet 16.” The show follows teenagers as they painstakingly plan their elaborate celebrations, which cost as much as $200,000. There are tears and tantrums and nouveau-riche displays of conspicuous consumption. Marissa, a daddy’s girl from Arizona, dyes her two poodles pink, so they’ll match her dress.22 The other end of birthday party economics revealed that 21% of Chuck E. Cheese customers spent between $225 and $300 on parties for their kids. A vast majority of that spending—62%—went toward games rather than food.23

– Steven Schwarzman, CEO of Blackstone, threw himself a $5 million 60th birthday party at the Park Avenue Armory in February 2007. It featured marching band entertainment and a 50-foot silkscreen re-creation of his apartment.24

And it wasn’t just the conspicuously wealthy who were bitten by the overindulgence bug. Americans of all socio-economic levels joined in. People who appeared as if they weren’t sure where they would sleep at night were spending their days chatting away on their cell phones or listening to iPods. Don’t believe that one? Take a stroll down Santa Monica, California’s 3rd Street Promenade sometime, where I have seen throngs of vagrants find a welcoming environment, or the backyard of the typical American middle-class neighborhood.

Before the Meltdown of 2008, America was booming. Just for fun, let’s listen in on an imaginary conversation during a backyard barbeque, circa 2005....

Jim: Nice place, Jack.

Jack: Thanks. It took a long time to finish the renovation, but it was worth it.

Jim: What took so long?

Jack: You mean besides my wife’s inability to make a decision on the color of the deck stain? And the barbeque being on back order for, well, forever? All good now, though. Adds value to the home, too, right?

Jim: Yep, that’s what the TV shows call curb appeal. Like putting money in your bank account. We put in some landscaping, too. My wife wanted a water feature, which seemed silly to me until I realized I could use that against her and get the putting green I always wanted.

Jack: Nice. You can settle in on a Saturday afternoon with a beer and work on the short game.

Jim: You know it. That’s what I did today.

Jack: I played Xbox with my son. I swear; kids are hard-wired to play those video games.

Jim: We’re a ways away from the video games. I’ll have to come down to your house over the next couple years and practice, so my boys don’t wipe the floor with me. Who knows what they’ll come up with next?

Jack: Whatever it is, you can bet my kids will have to have it, and we’ll ante up. I just wish they’d come up with a game to get them moving while they’re playing. I hate to see them sitting so long. Hey, how about a margarita?

Jim: Sounds good. That looks like a blender from the future. High tech.

America’s Spending Bust

From boom to bust, the days of wine and roses came to a crashing halt, and a generation of spenders woke up with one giant hangover, starting in 2008. As comedian Jackie Mason said, “Right now I have enough money to last me the rest of my life, unless I buy something.”25

• Four in ten Americans now feel buyer’s remorse—wishing they had spent less money during good times and put more away over several years.26

• Average American household credit card debt equals $8,565, up almost 15% in 2008 since 2000.27

• Americans have $10.5 trillion in just mortgage debt since the end of 2007, more than double the $4.8 trillion in 2002.28

• The big buzz kill.

– According to a survey by Lightspeed Research, 60% of Americans have scaled back on fancy or expensive coffee in the past six months; 43% of those completing the survey indicated that they frequented Starbucks the most.29

– For the first time, annual sales of flat panel TVs looked to decline from $24.4 billion in 2008 to $21.8 billion in 2009.30

– Hummer’s U.S. sales tumbled 51% in 2008—the worst drop in the industry.31 “It’s a brand that represents a lot of what people want to get away from,” said Rebecca Lindland, an analyst with the research firm I.H.S. Global Insight. “Even if gas prices are lower, it still kind of radiates conspicuous consumption.”32

• The party is over.

– “My Super Sweet 16” has been canceled and many parents find themselves relying on the “less is more” ethos this time around, and parents are increasingly gravitating to lower-cost shopping options, from Wal-Mart to secondhand stores.33

• Back to basics.

After the meltdown, necessity and luxury were redefined, as many consumers got back to basics.34

– 57% of people bought less expensive brands or shopped more at discount stores.

– 28% of people cut back spending on alcohol or cigarettes.

– 24% of people reduced or canceled cable or satellite TV subscriptions.

– 22% of people changed to a less expensive cell phone plan or canceled service.

– 21% of people made plans to plant a vegetable garden.

– 20% started doing yard work or home repairs that they used to pay for.

– 16% of people held a garage sale or sold items on the Internet.

– 10% of people had a friend or relative move in or moved in with them.

– 2% of people rented out to a boarder.

Now, let’s listen in on that imaginary conversation at a backyard barbeque, circa 2009....

Jim: I understand your house is on the market.

Jack: It was, but we accepted an offer yesterday. But don’t tell anyone. The neighbors won’t be happy with the price. We’re losing a little, but I think we’ll make it up when we buy again somewhere.

Jim: You just wanted out, huh?

Jack: Well, after we put the pool in....

Jim: I thought you loved your pool.

Jack: It’s a lot of work. We weren’t even going to fill it up this summer.

Jim: I’m sure the new owner will.

Jack: Don’t be so sure. The guy’s a landlord—he bought the house to rent it out. Might fill in the pool.

Jim: Ooooh, really? Where are you moving?

Jack: Wherever a job takes me. It’s sort of one project at a time. First was selling the house; tomorrow is my youngest daughter’s birthday party.

Jim: What are you gonna do for that? Chuck E. Cheese again or Build-a-Bear? That’s what my daughter has been screaming for.

Jack: No, I think we’re just going to have some of her friends over. You know, play some games.

Jim: I hear ya. I took my son’s party to the amusement park a few weeks ago...should’ve taken out an installment loan. Wow!

Jack: Yea. I’m going to miss the neighborhood.

Jim: Well, don’t lose touch.

Jack: I won’t. Let’s get a beer.

Jim: Or two.

The Retirement Brain Game

Mental Accounting—So we spend too much and save and invest too little. And when we do this, we often make mistakes, even though our intentions are good. Behavioral finance studies show that some financial errors can be attributed to a behavior known as mental accounting. Imagine an inbox inside your head where you store accounting files, and you label your mental folders, assign them values, and make financial decisions based on them. For example, emergency money, bill money, birthday money, gas money, fun money—you get the idea. In and of itself, categorizing money is not a problem; however, as we will see, mental accounting can become a detriment when it influences the way we spend, save, and invest money. Mental accounting can influence decisions in unexpected ways and can keep us from maximizing the dollars in each account.

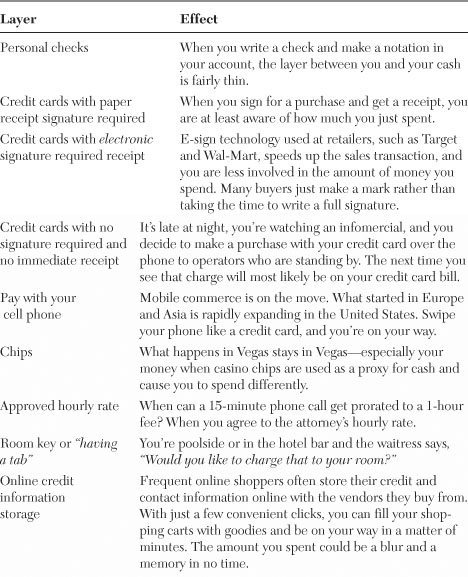

Layering—In behavioral finance, layering refers to the way people treat their money when they’re not dealing with actual money, but rather proxies for money. Using checks, credit cards, or room numbers at the hotel while lounging about the pool are all ways that consumers can create psychological layers of distance between themselves and their money. Or people may give a green light to an hourly fee without knowing the total amount of cost. All these different ways to pay make money more and more opaque to consumers and provide perfect examples of layering.

Tic-Tac-Dough

In one of our focus groups, a participant told us she was well aware of the potential damage of revolving debt with exorbitant interest rates. And she proudly proclaimed that she had no such debt. She told us that she paid her monthly bills on time, paid off the balances of her department store credit cards, and even kept a savings account that she only touched for emergencies. But as our research team continued quizzing her, she revealed, almost as an aside, that she kept a balance on her VISA, “Because that was different.” What’s different? Granted, in this economy, more people are feeling the need to keep a “rainy day” account in case of job loss, which is a perfectly rational idea on the surface. But does this make good financial sense when you drill down? Keeping a “rainy day” account in a low-interest savings vehicle, while still paying on another account, like a high-interest credit card or loan, can be a losing proposition because of the potential cost of that high interest. When you crunch the numbers, you may see that you are better served paying the high interest account in full with the savings. For example, if she is paying 16% a year in interest on her credit card but earning only 2% on her emergency fund, that’s a yearly loss of $140 for every $1,000 spent. It adds up. The way we mentally account for our money, however, can prohibit us from parting with the safety net. The good news is that mental accounting can be used in a positive manner. I’ll discuss how you can turn the pitfalls of mental accounting into a benefit, and for the sake of this discussion, I’ll refer to that as mental budgeting.

One measure that proves useful in understanding how we mentally account for money is how transparent or opaque the given question is. The more transparent the money question is, the more conscious we are in our decision making. The more opaque it is, the easier it is to make less conservative decisions with our money. For example, how many times have you selected an on-demand movie that you would probably never have rented from the video store? The automatic billing catches up with you on the monthly invoice and, if you’re like many, you’re shocked by all the extra charges. But each month, with the remote in one hand and popcorn in the other, you do it again.

When an amount of money is extreme, either extremely small or extremely large, we tend to account for, and spend it, differently as well. For example, would you overpay for an item by 300%, 400%, or 600%? Ridiculous, you say? When the amount of money is relatively small, you might. Millions of Americans do it every day by raiding the hotel snack bar, for example. Isn’t $8 a bit steep for a chocolate bar that costs just $1.50 in a convenience store down the street? How about when amounts are extremely large? Do you think people spend extremely large amounts frivolously? Well, of course they do. Think about a car purchase. People feel they need their options like heated seats and extra cup holders with independent suspension so that their decaf vanilla lattés with extra whipped cream don’t spill. These “while you’re at it” additions can pile thousands more dollars onto the price of the car. However, because they increase the monthly payments by only $20 or $30, people allow them to add up almost without thinking.

Car buyers are already spending a considerable amount of money—what’s a little more? Registration, taxes, interest rate, delivery to lot, and insurance are some of the costs that are often overlooked. Many car buyers never actually see the money they’re spending. The dollars they envision are merely represented by a number that’s subtracted from their monthly budget, as opposed to actual dollars that are removed from their pockets and turned over to someone else. They say, “Hey, I’m already spending $44,000. What difference does another $2,000 or $3,000 or $4,000 make? What, $775 for the sunroof? Sure, gotta have that.” A fancy new GPS navigation system can run as much as $4,000, but buyers don’t often perceive it that way. They figure that if they’re going to spend nearly $44,000 on a car, how’s an option that’s less than 1/10 the price really going to have a significant impact on the total price? When your ultimate destination is retirement, it may be cheaper to buy a map.

The Proxy Perception

Using checks, credit cards, or room numbers at the hotel while lounging about the pool are all ways that consumers buffer themselves from how much they’re really spending. All these different ways to pay make money more and more opaque to consumers and provide perfect examples of layering. Layering is used as a money-laundering term that refers to layers of separation from the place where it was originally “earned.”

Just as Las Vegas has learned that people will toss chips around far more liberally than cash, the credit card industry knows very well that people treat those little ![]() inch-by-2¼ inch plastic rectangles very differently. Buyers are more apt to whip out their plastic, not just because the fiscal impact of the purchase is muted, but also because it’s simply quicker and easier to pay that way. Think about retail transactions in the 1970s: The cashier would ask, “Cash or check?” You would then pull cash out of your pocket and turn it over to the cashier who would go through an elaborate counting exercise in his head because calculators weren’t widely available, before giving you too little change—or too much change, in which case you would walk out of the store as quickly as possible. You could also write a check, which extended the checkout process by eons as you presented two forms of I.D. and wrote down the amount of it in your check register. Writing a check removed you from the hurt of seeing actual money leave your possession, but at least you were keeping track of your balance. Hmm, when is the last time most Americans balanced their checkbooks? Quaint little notion, isn’t it?

inch-by-2¼ inch plastic rectangles very differently. Buyers are more apt to whip out their plastic, not just because the fiscal impact of the purchase is muted, but also because it’s simply quicker and easier to pay that way. Think about retail transactions in the 1970s: The cashier would ask, “Cash or check?” You would then pull cash out of your pocket and turn it over to the cashier who would go through an elaborate counting exercise in his head because calculators weren’t widely available, before giving you too little change—or too much change, in which case you would walk out of the store as quickly as possible. You could also write a check, which extended the checkout process by eons as you presented two forms of I.D. and wrote down the amount of it in your check register. Writing a check removed you from the hurt of seeing actual money leave your possession, but at least you were keeping track of your balance. Hmm, when is the last time most Americans balanced their checkbooks? Quaint little notion, isn’t it?

Many Boomers may recall when cashiers counted change as they handed it to you—but they counted back to the amount you had originally given them. In other words, accounting protocol dictated that if you gave the cashier a $20 bill for an $11.19 purchase, she should count back to the original $20 amount by adding your change to the total purchase amount as follows, “Here’s the 81 cents, that’s 12; 3 dollars, that’s 15; and five makes 20.” That isn’t what happens now, is it? Now the cashier will virtually never count your change at all. And if they do, they merely count the change out loud as they are handing it to you. “Here’s 5, 8, and 81.”

A swipe here and a swipe there and pretty soon you’re talking real money.

Nowadays there’s no waiting at retail and little appreciation of how much you’re spending; you just swipe a credit or debit card and go. At the gas pump, at the fast food drive-thru, at the grocery store, we have become a “Just Swipe It” generation of spenders. And to further remove you from how much you’re spending, a signature is seldom required for everyday purchases; in fact, the whole transaction is lightning quick, very convenient, and very opaque. Have you noticed how more and more checkout screens at retail stores are positioned in a way that the cashier can see what each product being scanned costs, but the customer cannot?

I was at a club-type store recently and noted that many of the departing customers were hurriedly scanning their receipts and checking prices as they pushed their carts toward the person at the door who matches their receipts with the goods in their carts. After all, this information was not available to them at the checkout station. And at this point, what happens when one of these consumers discovers that he was charged $3.79 for an item he is sure was supposed to cost $3.29? Is he going to get out of line, shuffle over to customer service, and spend the next 15 minutes getting his 50 cents, or is he going to push his cart on out to the car? And when there is a choice of receiving a receipt or not, many of us decline the offer of a receipt and arrive home with absolutely no idea how much lighter in the wallet we are. You have to wonder, if most consumers continue to decline receipts, will the default change? Will the customer be required to ask for the receipt in the future? Will gas pumps eliminate your option to print out a receipt? Or will we be told a receipt will be sent electronically? Years ago, the Apple Store started sending receipts to customers’ e-mail accounts so that they could print them out if they wanted them, and there is a movement afoot to make “e-ceipts” a part of the retail landscape through an embedding of information in your credit cards. I am convinced that receiving a paper receipt is going to continue to be less and less common. At the gas station I frequent, the last question from the machine is “Do you want a receipt?” Yes, I know it will show up on my credit card anyway, but I hit “Yes,” mainly because I don’t want the option to go away—and my thinking is that if enough people keep hitting “No,” the option will be eliminated.

Of course, there could be all sorts of fraud and privacy issues that would need to be overcome for e-ceipts to become common. And it is possible for layering technology to go haywire on its own without criminal intervention. For example, people who frequent toll roads often buy toll transponders and attach them on the dashboard of their cars so they don’t have to stop and pay at the tollbooth each time they pass. We had a focus group participant who told us how the chip in her brother’s transponder went haywire and kept overcharging him for multiple passes. The transponder account was set up so that the money came directly out of his checking account, and before he realized what had happened, her brother was $10,000 in debt. The woman’s brother had to move in with her and hire a lawyer as the situation, still not resolved, has put the entire family in financial straits. This gentleman may have avoided this predicament if he’d paid at the tollbooth, or perhaps more importantly, paid closer attention to money flowing automatically out of his checking account. The layers that he put between himself and his money caused him to, in a way, fall asleep at the wheel.

Paying with a check. Paying with a credit card. Paying with those pinky-sized credit “cards” that dangle from your keychain. Paying by text message. Swiping your cell phone like a credit card. Who knows, someday we may simply think of a purchase and charge it. That might sound a little sci-fi, but there are now so many ways to pay because marketers are doing whatever they can to make it easier for customers to give in to impulse. For example, my wife and I were recently convinced to go on the first cruise in our lives—Vancouver to Alaska. Our friends, who are cruise veterans, assured us that this particular ship was the top of the line and that it would be an excellent vacation experience. They were right. There were daily excursions with exotic things to do, such as viewing glaciers, fishing salmon-filled rivers, bear watching, and more. All these adventures and thrills, of course, come at a significant extra cost. The cruise does a marvelous job of arranging and masking various combinations of these activities, so it is rather difficult to discern precisely how much any given outing costs. In fact, I was introduced to many new procedures and expenses as the lines blurred from one fun package to another. But, most intriguing is the $2,000 of upfront money called “ship credit.” What a concept. You pay for ship credit in addition to the excursion packages, and in advance of the cruise, so that you’ve already parted with your money before you even begin. You can supposedly get money not spent back at the end of the cruise; however, the process is so complicated (standing in long lines, negotiating credit that will be returned to you) that it becomes easier to simply spend the ship credit that you originally purchased. That’s the idea—to spend the money. Our friends, in fact, declared at one point, “Well, we still have $150 left, we should stop by that jewelry store.” From a psychological standpoint, they had already recategorized that money as something other than their own.

As we’ve seen, layering can cause different degrees of separation from your money, and layers can be added between you and your cash by both proxy and by permission. The point is, the thicker the layers, the more opportunity there is for poor financial decisions. As we’ve discussed, layering can affect the way you make purchases and how you pay for labor. Table 2.1 starts with thin layers and shows how spending becomes more opaque as the mental layers get thicker.

Table 2.1 Psychological Levels of Layering

The Retirementology Cash Challenge

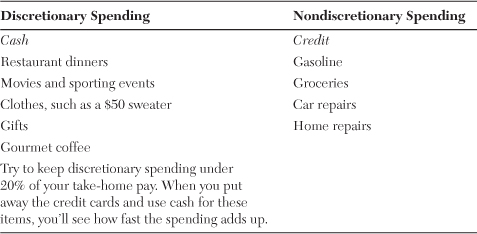

If you’re still unsure how the format of money makes a huge difference in the way you spend, take the Retirementology Cash Challenge. Put away your credit cards, debit cards, and even checkbooks, and try using only cash for a week. The amount of cash you realize you are spending will be eye-popping, but even so, you will most likely return to your credit or debit cards for the sake of convenience. If you must use plastic, which we all do, consider organizing your purchases in the following manner:

Let’s take the Retirementology Cash Challenge one step further. What if I challenged you to spend no more than $100 on food for an entire week, and I gave you a $100 bill. If you accepted that challenge, my guess is that you would have an extremely good idea of how much you had spent and had left at the end of, say, Day 4. Further, you would have a very clear idea of whether a purchase of a $7 cheeseburger made sense about now. But many people are so distanced from their funds—by electronic statements and layered forms of payment—that they really aren’t sure how much they’re spending, how much they owe, and how much they have left. Their funds show up automatically and electronically in their accounts. Many of their bills are paid the same way. The balance ebbs and flows without the consumer having a clear understanding of whether flow is exceeding ebb—or by how much. One of the best steps people can take is to simply dig in and get a very clear picture of all this. Do you know precisely how much money you owe right now—credit cards, mortgage, and so on? Do you know what your average monthly spending was last year? Do you know how much of this was discretionary? Do you know what your average monthly net income was last year?

Improve Your Retirementology IQ

People make plenty of errors when it comes to setting a financial plan for retirement. You can improve your Retirementology IQ by recognizing the following common mistakes:

Mistake #1: Are you spending too much? The first error of anyone planning for retirement or just budgeting between paychecks is, of course, spending too much. Simple first-grade math should tell anyone that overspending will only get you in trouble. Although the Greatest Generation didn’t have access to all the sophisticated financial instruments we have today, they did exhibit one thing very well—they lived within their means. That’s a lesson that’s as valid today as it was during the Great Depression.

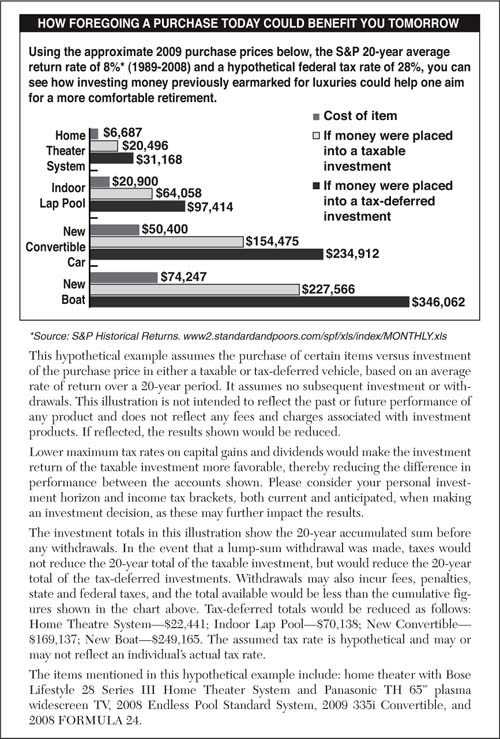

Before you consider purchasing a home theater system, new car, or remodeling your home again, think about how much that luxury could potentially cost your retirement. Chances are your lifelong spending has a greater impact on how you retire than you are aware. In Figure 2.1, let’s take a look at some spending boom luxury purchases and what they are really costing your retirement. Is that luxury really a necessity?

Figure 2.1 To Buy or Not to Buy

Mistake #2: Are you setting a budget? Much of the past six decades have seen the American economy grow. As a result, many people’s incomes have grown and their lifestyles have gotten more and more lavish: It’s hard to believe a member of the Greatest Generation would have treated himself to a “spa day,” but such an indulgence is fairly common now. Setting a budget allows you to prioritize the importance of what you need and want. If a spa day is important, what would have to be cut? Too often, this trade-off is excused as everything is put onto a credit card and a minimum payment is made at the end of every month. The problems that can emerge from such a lack of discipline are legion, but they can be easily avoided with a simple budget. A weekly budget, a monthly budget, even a yearly budget allows you to see where your money would go before it goes there; that allows you to decide just how important some things are to you.

Mistake #3: Are you keeping high-interest credit card balances? Credit is not money. It’s not the same as cash being dropped into your account. Credit is to be used only if it can get something for you that is more valuable than what you spend to get it. Otherwise, using credit becomes nothing more than an unnecessary expense that can cost you the retirement you’re after. Some people will set aside cash in a low-interest account for an “emergency” or “rainy day” fund and that’s fine. But not if that account is earning a fraction of the interest that you’re paying on your high credit balance. A high credit balance is a parasite on all other savings and investments; it’s imperative that you eliminate that balance as soon as possible, starting with the balance upon which you’re paying the highest interest...then build up the cash reserve. Start with your highest interest balances and pay those off; then move to your next highest interest balance, and so on.

Mistake #4: Are you keeping low insurance deductibles? It may seem attractive to you to have a low deductible for your car and home insurance. If you have an accident or a fire, for instance, you only have to pay a small amount of money toward getting your situation rectified. The price you pay for such a low deductible is, however, a much higher premium. That means more money coming out of your monthly budget, money that can be doing much more good going into your retirement accounts and earning compound interest. Push your deductibles as high as you can, and you’ll have better control of your money.

Mistake #5: Are you keeping a high balance in your checking account? If you keep a great deal of money in your checking account, the size of any given check you write looks a lot smaller. If you have $5,400 in a checking account, a $532 check looks rather large. In fact, it changes the first number on the balance, which keeps your attention. But if you are holding, say $100,000, in your checking account, that check barely puts a dent in your account, and that makes it easier to keep writing checks and to lose accountability for what you are spending. Effective October 3, 2008, the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 increased the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s (FDIC) coverage limit to $250,000 per depositor. This limit will revert to $100,000 on January 1, 2014. In my opinion, that is probably a lot more money than a smart saver should ever have in a checking or savings account.

Enjoy the Sushi...Just Hold the Gold Dust

A comfortable retirement is available to just about any American who shows just a little self control. Sure, you’re going to spend money—there is no free lunch...or dinner, for that matter—but after you pay your taxes, you do have control over how much you spend. The fact is that many experts cite controlling spending as the single most important ingredient to building wealth. In their classic book, The Millionaire Next Door, Drs. Thomas Stanley and William Danko describe a person who controls his spending as “playing good defense.” Indeed, the bankruptcy courts are full of people who have won or earned a great deal of money, but their taste for living the high life is what drives them into financial trouble.

Curb Spending

Do you really need that triple mocha latté with sprinkles for $3.50 every morning? On a larger scale, what about the heated seats with the Magic Knuckles massage system on every seat in your new car? Sure, this luxury adds only an extra $50 onto an already big $900 monthly car payment, so it doesn’t feel like it’s really hurting your budget...especially when you’re getting a massage as you roll down the road. But a little here and a little there can add up to real money and cost thousands of unnecessary dollars in the long run. That’s money that could be growing and helping you accumulate even more for retirement. If you really do need to spend, spend your dollars wisely.

Mental budgeting. My father taught me the game of chess as a child, and at one point in my life, I was quite an enthusiast. I purchased one of those chess computers from Radio Shack that beat me with infuriating consistency. The problem, of course, was that the computer could sort through the labyrinth of combinations much more quickly and clearly than I could. But I found that the one way I could actually win, though rare, was to reduce the complexity of the puzzle. I would set a game plan in place specifically attempting to trade as many evenly valued pieces whenever I could—a knight for a bishop, a pawn for a pawn, a queen for a queen. In this way, I was reducing the number of decisions available. Extrapolating this, if I could reduce the game to a point where we each had a king and three pawns remaining, my odds of winning were greatly improved. Similarly, I believe you can implement this type of strategy from mental accounting that can be a very positive and soothing technique for managing your expenses. For example,

• The $437 per month received from my pension at my old employer is my dining out fund.

• This year’s bonus is our “new car” fund.

• The dividend from the oil and gas stock funds our long-term care insurance.

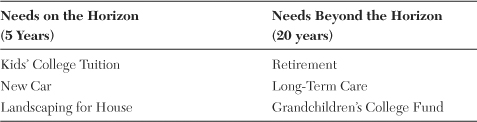

Use mental budgeting to your advantage. Setting a budget for a week or a month is a great way to curb spending. Setting a top-end price that you’re willing to pay for a big-ticket item is also a way to keep yourself from spending money that could better be put toward retirement. Mental budgeting can help you determine different needs and time horizons for different pools of money. It may be to your advantage to budget with a purpose, with a firm timeframe and an acknowledgment that your total budget and wealth plan is composed of different parts that have a purpose and are uniquely suited to your overall retirement objectives.

Use Financial Automation

In 1934, an R.H Macy & CO. executive and New York Fed director named Beardsley Ruml developed a plan whereby the U.S. Treasury would remove a certain percentage of money from every American’s paycheck to pay that person’s taxes.37 The government got the money before the worker did and the age of automatic withholding was born. IRS aside, you can use the power of automation for saving and investing, as it simplifies the process for building a retirement nest egg, encourages disciplines such as dollar cost averaging, and keeps the focus on a long-term retirement perspective. It should be noted that dollar cost averaging does not guarantee a profit or protect against loss in a declining market, and it involves continuous investing regardless of fluctuating price levels. So, you should really consider your ability to continue investing through periods of fluctuating market conditions. However, by automating your contributions, you can better assess how much money you have to spend on day-to-day items. Remember, a retirement nest egg is like a bar of soap; the more you touch it, the smaller it gets. Don’t peek and keep it out of reach.

Regularly Increase Your Contribution Rate

The automatic payroll deduction structure of 401(k) accounts can help investors stick to a more disciplined retirement plan. Professor Richard Thaler of the University of Chicago, and Professor Shlomo Benartzi of UCLA, took this strategy one step further. They created a program called Save More Tomorrow (SMarT), which is currently being adopted by some 401(k) providers. Under this program, workers agree to boost their 401(k) contributions automatically by two to three percentage points with each annual raise. During a four-year test of the SMarT Plan at a mid-sized corporation, participants’ average contribution rates jumped from 3.5% of their pretax pay to 11.6%.38

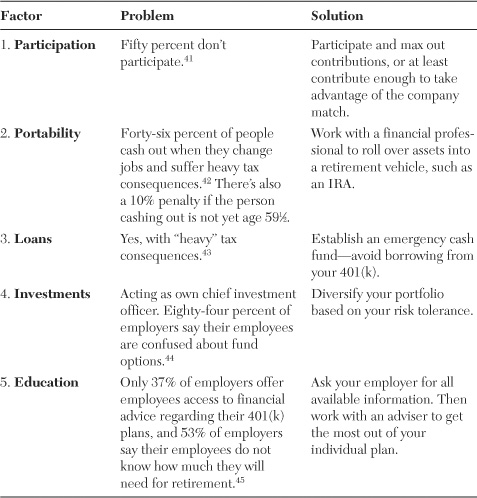

With the passage of the Pension Protection Act (PPA) of 2006, companies began using automation to increase participation in their qualified plans. Instead of just promoting the plan and waiting for participants to sign up, many employers have begun to automatically enroll employees. Research shows when automatic enrollment is implemented, participation can reach 95%.39 Although company automation is a powerful tool and has helped jumpstart plan participation for many workers who may have otherwise procrastinated, the PPA also opened the door for automated processes such as auto-default and auto-advice, which can both lead to problems. When auto-enrolling workers, many companies set the default rate too low, for example 3%. Although something is better than nothing, a low contribution rate can prevent participants from earning company matches, which means you could be losing out on free money if you don’t adjust your contribution rate. The automatic advice that many companies offer is likely in the form of hard-to-follow sales literature, often presented by a human resources employee, rather than a financial professional. If you choose to do nothing, auto-enrollment could lead to a low default rate and an auto investment selection that may not be right for you. For example, in recent years, target date funds have been the default du jour for 401(k) plans, and unfortunately, they were down as much as 40% last year,40 so they haven’t fared any better than most other investments. It’s no secret that 401(k)s, in general, took a beating during the market meltdown, but they are still one of the most effective tools for building your nest egg over time—especially if you work with an adviser and take full advantage of what your company has to offer.

Consider the following five factors with your retirement account.

RETIREMENT ISN’T A SINGULAR EVENT—SPENDING

IN YOUR 20S, 30S, AND 70S HAS AN IMPACT ON YOUR

RETIREMENT. FURTHER, RETIREMENT ISN’T

ISOLATED—WHAT YOU SPEND ON A VACATION OR

CAR MAY IMPACT YOUR RETIREMENT LATER.

Endnotes

1 Hopkins, Jerry, Anthony Bourdain, and Michael Freeman, Extreme Cuisine: The Weird & Wonderful Foods That People Eat, 2009.

2 Gold Bulletin, “Gold leaf tops $1,000 sushi roll,” April 17, 2008.

3 Cooking Resources, “Cooking With Edible Metals Like Gold, Silver,” October 29, 2009.

4 Gold Bulletin, “Gold leaf tops $1,000 sushi roll,” April 17, 2008.

5 Business Week, “After the Housing Boom,” April 11, 2005.

6 Credit Card News, “Ditching credit cards right move for some,” September 22, 2008.

7 NPR, “Credit Card Companies Raise Minimum Payments,” November 4, 2005.

8 The New York Times, “Economy Fitful, Americans Start to Pay As They Go,” February 5, 2008.

9 The New York Times, “Given a Shovel, Americans Dig Deeper Into Debt,” July 20, 2008.

10 The New York Times, “Given a Shovel, Americans Dig Deeper Into Debt,” July 20, 2008.

11 USA Today, “Obama team makes it official: Budget deficit hits record. By a lot,” October 16, 2009.

12 The American, “Debt Be Not Proud: The Sorry Tale of America’s Out-of-Control Spending,” September 7, 2009.

13 Brillig, U.S. National Debt Clock, as of January 14, 2010.

14 Market Watch, “Financial fears grow,” March 20, 2009.

15 Market Watch, “Financial fears grow,” March 20, 2009.

16 Market Watch, “Financial fears grow,” March 20, 2009.

17 Yahoo! Finance, Starbucks Corp. (SBUX): Historical Prices, Jan. 1, 2007–Dec. 31, 2007.

18 Navellier Growth, “As Starbucks (SBUX) Stumbles, Green Mountain Coffee Roasters (GMCR) Shines,” April 16, 2009.

19 Broadcast Engineering, “Big-screen LCD TV sales grow in 2007, research firm says,” February 19, 2008.

20 Recreational Boating & Fishing Foundation, Boating & Fishing Facts, 2006 Recreational Boating Statistical Abstract, 2007.

21 The New York Times, “Hummer’s Decline Puts Dealers at Risk,” March 31, 2009.

22 The New York Times, “MTV’s ‘Super Sweet 16’ Gives a Sour Pleasure,” April 26, 2006.

23 iStock Analyst, “Retail Survey Report: Cache Stores, Chili’s, Chuck E. Cheese,” July 23, 2008.

24 What It Costs, “Top Ten Most Expensive Parties Ever Thrown,” 2009.

25 Answers.com, “Jackie Mason,” 2009.

26 MetLife, “The American Dream has been revised not reversed, pragmatism is replacing consumerism as the bar stops rising/buyer’s remorse sets in, according to third annual MetLife study,” March 9, 2009.

27 The New York Times, “Given a Shovel, Americans Dig Deeper Into Debt,” July 20, 2008.

28 The New York Times, “Given a Shovel, Americans Dig Deeper Into Debt,” July 20, 2008.

29 Fare Magazine, “Consumers Cut Back on Coffee Spending,” January 30, 2009.

30 Ventura County Star, “Stores out to tempt TV buyers this week,” January 25, 2009.

31 The New York Times, “Hummer’s Decline Puts Dealers at Risk,” March 31, 2009.

32 The New York Times, “Hummer’s Decline Puts Dealers at Risk,” March 31, 2009.

33 San Diego Union-Tribune, “Parents scale back luxuries for children,” June 14, 2009.

34 Pew Research Center Publications, “Luxury or Necessity? The Public Makes a U-Turn,” April 23, 2009.

35 CreditCards.com, “Implantable credit card RFID chips: convenient, but creepy,” August 5, 2009.

36 Notable Quotes, Quotes on Las Vegas, from The Joker Is Wild, 1957.

37 Encyclopedia definition of Ruml, Beardsley, 2009.

38 Thaler, Richard, and Shlomo Benartzi, “Save More Tomorrow: Using Behavioral Economics to Increase Employee Saving,” November 2000.

39 WebCPA, “Automatic 401(k) Enrollment Is Not for Everyone,” October 27, 2009.

40 The New York Times, “Target-Date Funds: Seven Questions to Ask Before Jumping In,” June 29, 2009.

41 Pensions & Investments, “Special Report: The Looming Retirement Disaster,” April 18, 2005.

42 Hewitt, “Hewitt Study Shows Nearly Half of U.S. Employees Cash Out Their 401(k) Accounts When Leaving Their Jobs,” October 28, 2009.

43 USA Today, “401(k) loans come with caveats,” October 11, 2007.

44 Watson Wyatt, “The Defined Contribution Plans of Fortune 100 Companies: 2008 Plan Year,” Research Report – December 2009.

45 Watson Wyatt, “The Defined Contribution Plans of Fortune 100 Companies: 2008 Plan Year,” Research Report – December 2009.