3. The NoZone

Imagine it’s the championship game with 10 seconds left on the clock and your team is down by 2 points. The quarterback is taking one last snap to move the ball a little closer to the goal line to set up a winning field goal. Your team is in the red zone, which in football signifies that a team is within 20 yards of the goal line, and where statistics show your team scores a high percentage of the time. But what if...the quarterback takes a bad snap and fumbles; the other team recovers the ball, takes possession, and holds on for the win. Shock. Dismay. Disappointment. Game over.

For the past few years, several financial firms have borrowed the red zone metaphor from football, referring to the five years before and the five years after someone’s retirement as the red zone, and popularizing the notion that the few years remaining prior to retirement are somehow the most critical to a successful retirement. Then along came the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression, and millions of Americans’ retirement plans were sacked for a loss just short of the goal line—in this case, just as they were preparing to enter retirement. What has become clear is that solving the retirement conundrum requires attention much earlier than a handful of years prior to retirement...and will certainly continue well into retirement. In June of 2004, the Dow Jones Industrial Average, an index which is a price-weighted average of 30 actively traded blue-chip stocks that generally are the leaders in their industry, was over 10,000.1 During the next three years, it climbed above the 14,000 point.2 Numbers were dizzying. Investors were jubilant. Untold heights were ahead. Risk was nothing more than a board game we played when we were kids. And then...the meltdown. What’s happened in recent years has destroyed or delayed an entire lifetime’s worth of retirement plans. Now millions of Boomers may be seeing red, but there is no zone in sight.

Waiting until you’re in the so-called retirement red zone before you plan for retirement leaves you susceptible to bad luck or events over which you have no control. That’s because proper retirement planning doesn’t start five years before you finish work and end five years into retirement. Retirement is not an event, a compartment, or a zone. Retirement is a monetary process that takes a lifetime of preparation that is predicated by a lifetime of behavior when it comes to your spending, borrowing, saving, and investing. If you’re breathing and able to earn money, you’re in the zone right now. Those who wait until they get into the red zone to start preparing for retirement put themselves in a position where an unforeseeable event—a bad snap and a fumble, or a financial meltdown and flight to low-risk investments—can cost them the retirement they were expecting. The recent financial meltdown is a perfect example of an unforeseeable event, and it cost retirement investors untold millions of dollars...many of them were Boomers who lost great sums of money at a time when they could least afford it: just before or just after they entered retirement.

Planning for retirement and retirement income is more like a 50-year project than a 10-year project. In fact, the real red zone may well be the first 5 years of an investor’s earning years. Out-of-pocket expenses and obligations are fewer for a young person, and the money that’s invested then has more opportunity to grow thanks to the power of compounding. I discussed in preceding chapters how a person can invest a relatively small sum in her 20s and watch it grow to a much bigger sum than someone who starts investing in her 50s and puts in much more principal. Just think of how much can change in a short amount of time when you have a market downturn. Consumer confidence is one thing that went from high to low. The Conference Board’s monthly Consumer Confidence Survey is conducted every month by research company TNS Global. TNS surveys 5,000 U.S. households and asks five questions that determine the respondents’

• Appraisal of current business conditions

• Expectations regarding business conditions six months hence

• Appraisal of the current employment conditions

• Expectations regarding employment conditions six months hence

• Expectations regarding their total family income six months hence

For each question, the three responses from which to choose are POSITIVE, NEGATIVE, and NEUTRAL. The response proportions to each question are seasonally adjusted and, for each of the five questions, the POSITIVE figure is divided by the sum of the POSITIVE and NEGATIVE to yield a proportion, which they call a “relative” value. For each question, the average relative for the calendar year 1985 (the year it equaled 100)3 is then used as a benchmark to yield the index value for that question.4

But the Consumer Confidence numbers weren’t the only ones that dropped precipitously from 2007 to 2008. The Dow Jones Industrial Average also fell in a hurry during that time.

Then...pre-meltdown

• In November 2007, the Consumer Confidence Survey checked in at a rather robust score of 87.3.5

• On October 8, 2007, the Dow was at 14,043.6

Now...post-meltdown

• In October 2008, the Consumer Confidence Survey had dropped to 38%, the most pessimistic number in more than 25 years.7 In fact, 62% of American adults now believe that today’s children will not be better off than their parents.8

• On September 15, 2008, the stock market would begin a three-week slide that would see the Dow lose 2,937 points, or 26% of its value.9

The Retirement Brain Game

Regret and pride—People avoid actions that create regret and seek actions that cause pride. Regret is emotional pain. Pride is emotional joy. Is this causing us to buy high and sell low? Research indicates that two of the most troublesome emotions that plague investors are pride and regret.

Myopic loss aversion—One type of event in particular has overwhelming, disproportional impact on investors—loss. As we discussed in the Introduction, research shows that, on average, before people would be willing to risk loss, they would need to see their gains reach at least 2.25 times the potential loss. This is what led Dr. Richard Thaler to conclude that losses hurt 2.25 times more than gains satisfy. When most investors experience loss, they spend the rest of their lives in fear of it. Fear of loss dominates their thinking—fear of missing out, fear of looking stupid, fear of not winning—all dimensions of loss. Wanting to avoid loss is understandable, especially when it comes to something as important as your retirement plan. However, it doesn’t mean that avoiding loss should be the primary objective of your investment strategy.

Herding—In behavioral finance the concept of herding is all about chasing trends. Day in and day out, investors purchase a stock simply because the company is recommended by an analyst or because media coverage is elevated and pronounced. The idea being, “Everyone else is buying those shares, so why shouldn’t I?” Prior to the meltdown you should have been asking, “Is today’s hot trend a worthy gamble for my nest egg?” Since the meltdown, you may be asking, “Is the mattress the only place safe enough for what’s left of my money?” Why shouldn’t you be asking yourself these questions? Everyone else is. A related concept is the Odd Lot Theory, which is a technical analysis theory that’s based on the assumption that the small individual investor is always wrong. So when odd lot sales are up, it’s because small individual investors are selling as a herd—and that could mean a good time to buy.

Thrill, Euphoria, and Other Things That Make You Sell at a Loss

“Regrets, I’ve had a few,” as the song goes. When we miss a bus or a train or a plane by minutes, we’re much more upset than when we miss it by an hour. When we’re way behind, we have a way of giving into the fact that we’re not going to achieve what we were hoping to achieve and we make other plans; there’s no sting in the loss. There was a study conducted on the pain and anguish of Olympic silver medalists compared to bronze medalists. In a nutshell, at the end of a close race, a silver medalist always looked disappointed, whereas the bronze medalist looked proud that he would be on the medal stand at all. Why is that? How can people be happier about coming in third than second? Perhaps it’s a feeling of achievement; just achieving a place on the medal stand is more gratifying than coming up just short of achieving a gold medal.

In reality, a loss is a loss. But when just missing a connection or falling just short of a goal, the means can be more important than the end result. I have a friend whose wife was sitting in a restaurant when she realized her necklace had come off. She quietly looked around the table for it before calmly announcing to her dinner companions that the necklace was gone. After hearing a description of the necklace, another woman at the table said, “I saw one just like it in the rest room not 5 minutes ago.” Overcome by the possibility of being so close to retrieving her lost necklace, she ran into the ladies’ room to look for it, but the necklace was nowhere to be found, and the feeling of regret overcame her. Regret is a powerful emotion, but one that doesn’t always allow us to look at the past with objectivity. My wife’s friend was no closer to retrieving her necklace from the ladies’ room than she was when she first discovered it missing.

Regret often clouds our retirement planning. Behavioral finance expert Meir Statman said, “Emotions are useful, even when they sting.... But sometimes emotions mislead us into stupid behavior. We feel the pain of regret when we find, in hindsight, that our portfolios would have been overflowing if only we had sold all the stocks in 2007. The pain of regret is especially searing when we bear responsibility for the decision not to sell our stocks in 2007.”10 Many people were buying stocks at the end of the most recent bull market and started selling them as their value went down. Unfortunately, after a market downturn, many people fall into this pattern of buying high and selling low. Our fear, our confidence, and our emotions convince us to take irrational chances with our investments. We often pull money out of the market when the market goes down and wait until it gets back to its highs to buy again. We repeat the same pattern of buying high and selling low. If you’re doing this, you’re not alone.

Loss: A Cautionary Tale

What myopic loss aversion means is that we have become so short-sighted, so fearful of loss, so concerned with losing our money, that we often make no decision, or make the wrong decision—either of which may prove costly. For example, suppose your child just entered college and the $10,000 bill for his tuition is due. You can either sell Stock A, for which you paid $20,000 and is now worth $10,000. Or you can sell some of Stock B for which you paid $20,000 and is now worth $30,000. Which will you sell? Research indicates that investors will most often choose the latter—despite that the tax deduction would make selling the loser even more attractive.11 Why? Quite simply, Americans hate to lose! And how does this impact our expectations for investment returns? Today things are different. Now, people are scared. And how is this fear manifesting itself? It is causing investors to place disproportionate amounts of their portfolios into overly conservative investments. People have also stashed away a tremendous amount of cash in savings bank accounts and in the form of CDs and money markets. In short, most of us no longer want to destroy the market, we want to make sure that the market does not destroy us. We don’t care as much about gains as we do about avoiding further loss. Several years ago, it was about the fear of not participating. Today, it is about the fear of losing.

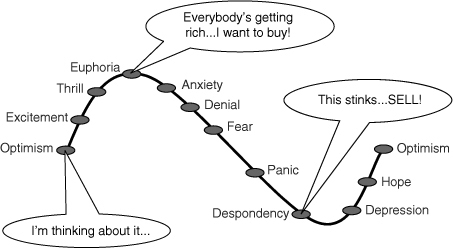

From the euphoria of a bull market, to the despondency of a bear market, investors often follow a cycle of market emotions that all too often results in buying high and selling low (see Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1 The Cycle of Emotions

Source: Westcore Funds/Denver Investment Advisors LLC, 1998 (emotional roll-ercoaster visual only)

ComPsych, one of the world’s largest providers of employee assistance programs, reported in 2008 that 92% of polled workers said financial worries were keeping them up at night.12 The 19th Annual Retirement Confidence Survey by the Employee Benefit Research Institute in April 2009 revealed that the percentage of workers who have lost confidence about having enough money for a comfortable retirement continued a two-year decline with only 20% saying they’re very confident. And that makes sense. The Institute revealed that 36% of workers 55 and older say the total value of their savings and investments (excluding the value of their home equity and any defined benefit plan they have) is less than $25,000. Whether that low number is a result of poor planning or the meltdown, clearly these future retirees have reason to worry. The report went on to say that 89% of Americans plan to change the way they manage their personal finances, and 94% say the meltdown will have a long-term effect on the way they manage their investments...not surprisingly, a vast majority of them (81%) indicate they’ll pull back and “play it safer with investments.”

There is a science to taking control of your retirement planning. It starts with understanding what you want to do, what gets in the way of your doing it, and what you can do to avoid those pitfalls. Consider a fundamental financial strategy called dollar cost averaging, which many investors practice without even realizing it when they make regular contributions to their 401(k), for example, and keep contributing no matter what the market’s doing. I’d like to reiterate that dollar cost averaging does not guarantee a profit or protect against loss in a declining market, and it involves continuous investing regardless of fluctuating price levels. Investors should really consider their ability to continue investing through periods of fluctuating market conditions. So how could such a machine-like approach to investing have anything to do with investor psychology? Well, it’s “not rational,” reported Meir Statman when speaking about automated investing, “but it is pretty smart.”13 Basically, engaging in a program of dollar cost averaging takes your mind away from the decision of what is the best time to invest because your mind has already made the decision when to invest. If you set up a program to invest on the first Monday of every month and the market goes down immediately after your first investment, you don’t have to worry because that only means that your second investment will allow you to buy even more shares. According to Statman, “the strict ‘first Monday’ rule removes responsibility, mitigating further the pain of regret.”14

According to research conducted by the University of Minnesota, people who are stuck in traffic feel better about the progress they’re making if they’re moving at a consistent 5 miles per hour than those having to constantly stop and go, and actually moving faster at an overall average of 10 miles per hour.15 The loss of a couple minutes here and couple minutes there while sitting still in traffic, it turns out, was so frustrating that the people surveyed didn’t appreciate the progress they were actually making. No matter what people are trying to do, anything that appears to slow down their progress toward that end is seen as a loss and is avoided at every opportunity. But what happens when you follow the driver in front of you without paying attention to the road signs?

Money in Emotion

If you were to get into the head of a lemming, who was hurling off a cliff to his death like all the other lemmings, the little rodent might be thinking, “Why wouldn’t I jump off a cliff? Everyone else is doing it!” What causes a stampede to start? A single piece of bad news can devastate a stock’s or segment’s value just as a single piece of good news can result in its value going up. The late 1990s and early this century brought us the “Dot Bomb.” Every day it seemed there was another 23-year-old kid who started a company with “dotcom” at the end of it who was suddenly an instant millionaire. Whatever.com, wake-up-late.com, latest-greatest-idea.com—wheeling-and-dealing professional investors, as well as individuals planning for their own retirement, gobbled up shares of these companies and asked for more. The market cap of these companies shot through the roof until a turn of events brought down the house of cards. Boom! The herding mentality reversed itself, and everyone sold shares, many for less than they’d paid because so many bought into the companies when they were heavily overvalued.

The Dot Bomb was just one of many bubbles in the annals of human beings hoping they could sell what they had to the greater fool and secure riches for themselves. Tulips, of all things, were one of the great early sources of wealth and the creation of a bubble. In 1624, about 60 years after rulers of the Ottoman Empire were first enchanted by the vibrant colors that could only be found in tulips, a Dutchman in Amsterdam turned down a great deal of money for a single tulip bulb. For the next dozen years, tulip bulb prices shot up—a farmhouse was purchased for just three bulbs—as auctions attracted more and more people who were more and more willing to purchase the flowers. Fortunately, however, the Dutch stock market did not deal in tulips, so the only people hurt were those who were left holding them when the price went down.16

One of the most compelling arguments against herding is that it can create just such a bubble, where the investment is pushed up to unreasonable levels based on emotional reasons rather than a logical estimation of worth. Take the nationwide housing bubble, for example. As home prices skyrocketed, investors poured in and snapped up properties to the tune of billions of dollars. In my opinion, even as housing prices continued to climb well above reasonable valuation levels, people piled in at a near frenzied pace. When the housing market cooled, however, those same investors fled in droves, collapsing the bubble. A herding mentality helped create the bubble, and that same herding mentality caused its eventual collapse, fueling one of the most ravenous foreclosure markets this country has ever seen.

And who got caught in the crosshairs? Everyday people, that’s who. Ordinary folks who were just trying to make a better life for their families suddenly found themselves upside down on their mortgages. And as the economy continued to shrink and shed jobs, many of those same people found themselves simply unable to pay the mortgage and put food on the table at the same time. Or worse yet, in their exuberance to get in on the hot housing market, they accepted ballooning adjustable mortgages that quickly grew beyond the constraints of the family budget. Innumerable other scenarios undoubtedly played a role, but the end result was undeniable: The bubble had burst, and a herding stampede had played a preeminent role.

Improve Your Retirementology IQ

These are scary times for an investor and for a retiree. But this is not the first time we’ve had an unnerving investment landscape. Understanding some retirement basics is a good start. Rather than following the herd, consider following these fundamental steps.

Understand Your Objectives and Assess Your Risk Tolerance

You must understand where you are in life, where you want to go with your financial future, and how much risk you are willing to take, or should take, to get you there. There are two key points to understanding your objectives: the anticipated cost of the objective and the timeframe you have to meet your objective. The absence of one of these points of reference makes it impractical to plan financially to meet your objective or to assign an appropriate level of risk to your investment decisions.

Traditionally, long-term investors have opted for greater risk on the belief that it would, over the right period of time, produce greater rewards. For example, historical data suggested that equity investments tend to outperform fixed income investments over time. However, the day-to-day volatility of the stock market generally makes equity investments a risky bet for short-term needs. In the context of retirement planning, equity investments provide long-term growth potential and a hedge against inflation but have greater volatility. Therefore, having equities as part of your retirement portfolio may be the right move. On the other hand, if you have immediate income needs or plan to draw income from your portfolio in the near future, investments that guarantee the return of your principal may be smarter, even though the actual rates of return on these investments may be less attractive.

It is also vital to weigh the importance of meeting your objectives within a given timeframe when considering risk. For example, if you would “like” to retire in five or six years, you may find that the financial resources you have available would require you to generate an aggressive rate of return on your investments to reach your objective. By accepting a high-level risk to meet your objectives, you may reach your goal, but you would have to balance that with the reality that poor performance or even losses on your investments may keep you from reaching your objective and may delay your retirement. In other words, if the due date of your objective is flexible, taking an additional risk for the chance of reaching it sooner may be an option. On the other hand, if your son or daughter is going to college in five years, taking on additional risk to meet the objective may not be all that responsible because the objective—your son’s or daughter’s college years—isn’t flexible.

You should also consider the level of risk that is required to meet the objective and only take on as much risk as required to meet your objective. For example, if we assume an investor had accumulated $2 million for retirement and his annual income needed in retirement was $50,000, his required rate of return on his investments would be 2.5%, assuming his objective is to preserve his principal balance. He could meet his income objective with very little risk. There is no need for him to take on additional risk to meet his objectives. Of course, not everyone is fortunate enough to be able to invest in low-risk investments and adequately meet income needs in retirement. For example, if we assume this individual had invested $500,000, he would need a rate of return of 10% each year to meet his retirement objectives. A 10% rate of return would require a substantially higher level of risk and, most likely, greater volatility. Your risk tolerance and the amount of risk you are willing to take when it comes to your retirement nest egg are important considerations when determining how much you need to invest and when you will retire. So, the less risk you can take to meet your objectives, the more comfortable you may be in meeting them. Understanding your own personal objectives and risk tolerance will help you overcome the desire to herd with the masses.

Set Long-Term Financial Goals

The achievement of any goal requires a plan. A goal without a plan is a wish. Where do you see yourself in 10, 20, or 30 years? An investment decision based on what happened during the fall of 2008 or the bursting of the dot.com bubble a few years earlier would be a very short-sighted way to invest. But many people based all their decisions on these events and turned what they had left into cash. The tragedy for many is that we’ve had a bull market since March of 2009, and many people have not participated. Hersh Shefrin wrote in his book Beyond Greed and Fear that short-term needs battle with long-term needs in any plan or budget. The short-term needs are right in front of people, almost screaming at them. Long-term needs are way off on the horizon; a faint voice that can barely be heard. The key to following a long-term retirement plan is to always pay heed to the voice that’s off in the distance because it will get closer and it will get louder and that will happen much more quickly than you think. If you start planning for retirement now, you’ll be glad later that you did. If you don’t start planning for retirement now, you’ll wish that you had. It’s that simple. Regardless of age, if you haven’t started accumulating money for retirement, you should start immediately, and put the potential power of compound interest to work for you. Further, if you haven’t done a basic analysis of how much you may need for retirement, you may want to put it on your to-do list.

Consider the following: If we assume that a person graduates from college at 23 and plans to retire at age 65, he has 42 years of full-time employment to prepare for retirement. If we assume that the average person lives to age 85, he will spend 20 years in retirement. In other words, you have approximately 2.35 years of income for every year of retirement. Given the difficulty many people have in just making ends meet throughout life as they save for their first house, raise their children, and eventually send them off to college, it’s not surprising that people often put off planning for retirement until they’re “older.” The problem is that when people feel they’re in a position to plan for retirement, they’re shocked at how much they need to accumulate to fund the retirement they desire. If you want to get a better idea of when you will be in a position to retire and what it will cost, you need to start planning as soon as you can get a plan in place. Plans help you stick to commitments and avoid regret, as well as the fear of loss.

Decide on an Asset Allocation Strategy

The road to your financial security is full of obstacles that you need to negotiate. Your asset allocation strategy can help you through these obstacles by helping you reduce the impact of market and economic volatility. An asset allocation strategy is synonymous with the old adage “don’t put all of your eggs in one basket.” As the last few years have taught us, markets and the overall economy can be volatile and hard to predict. Investing all your assets in one place or in one type of investment vehicle is closer to gambling than it is to prudent investing. By spreading your assets across multiple asset classes, you reduce the overall risk associated with just one asset class. An appropriate asset allocation also takes into consideration your risk tolerance, your financial resources, and your timeframe. The way you view or frame your portfolio can also help you diversify it. View your portfolio in the broad sense as a whole, rather than in a narrow sense, in pieces and parts. And view your portfolio as a long-term tool, rather than a day-to-day investment. In other words, “aggregation can reduce aggravation” when it comes to managing your portfolio.

Periodically Evaluate Your Plan and Strategy

Over time, it’s easy to get off course as your financial journey unfolds. You should periodically evaluate your direction to see if changes are needed. You may want to rebalance your portfolio from time to time to make sure that it represents the risk and diversification you desire. It’s very unlikely that your financial resources and financial burdens and responsibilities will follow a nice, neat linear path to retirement. There will be windfalls and there will be setbacks. For this reason, it is important to reevaluate your financial plan on no less than an annual basis. Try to pick a day, like New Year’s Day or your birthday or April 15th, to reassess your financial plan and see what changes should be made. Sitting down and doing a budget and creating a financial plan are good ideas, but you will find that any plan and any budget will become less and less applicable as time goes on. Your risk tolerance will change, your appropriate asset allocation will change, and your financial resources will change. Therefore, your plan will have to change accordingly if you want to meet your long-term goals and objectives.

Develop a Financial Plan

When you know the goal for your financial future, you need a road map to get there. Your financial plan provides the direction needed for this journey. Most people tend to avoid the “B” word at all costs. By the “B” word, I’m referring to a budget. Every financial plan starts with a budget, because before you can accumulate any money for retirement, you have to figure out where the money is going to come from. As I previously mentioned, finding enough money to make ends meet is difficult for most people, but you have to make retirement part of your budget. Setting money aside on a monthly basis is a start, but try to take advantage of retirement plans through your employer or by putting money into an IRA. There are limitations and penalties for removing money from these retirement vehicles prior to age 59½,17 hopefully making it a little more likely you’ll leave the money there until retirement. Use a financial planning calculator available on the Web or sit down with a financial planner to see where reallocating $25 a month will get you when you reach age 65. You probably won’t be thrilled with the result, but you’ll have a frame of reference from which to start. You’ll begin to see how much of a difference an additional $25 or $50 or $200 will have on your retirement, and you’ll begin to get a better understanding of what it will take for you to meet your financial goals at retirement.

Your plan will change over time as your financial situation changes. If you get a raise at work, consider increasing your retirement plan contributions. One good way to increase retirement contributions automatically is to make them a percentage of your salary instead of a dollar amount. Then, every time you get a raise, you increase your contribution. When retirement plan contributions are part of your monthly budget, you’ll find that you can get by on what’s left, and your retirement plan will start to take shape.

No one can tell what the future holds—who could’ve predicted the DJIA would drop from 14,000 to 6,600 in a little over a year? But a plan gives you an idea of how best to prepare for the future. Be honest about your goals. If you want to have access to $2 million cash on the day you retire, a house that’s paid off, a winter house on the beach, and a golf cart to drive to the store from your beach house, put together a plan that you believe will take you there. Remember, there is no one-size-fits-all solution; you have to develop a plan and select the investments that work best for you.

RETIREMENT ISN’T A ZONE; IT’S A CONTINUUM—ONE

YOU NEED TO START THINKING ABOUT

MUCH SOONER THAN FIVE YEARS OUT.

Endnotes

1 Yahoo! Finance, Dow Jones Industrial Average (^DJI): Historical Prices, Jan. 1, 2004–Dec. 31, 2004.

2 Yahoo! Finance, Dow Jones Industrial Average (^DJI): Historical Prices, Jan. 1, 2007–Dec. 31, 2007.

3 The Conference Board, “The Conference Board Consumer Confidence Index® Declines in October,” October 27, 2009.

4 The Conference Board, “Consumer Confidence Survey® Methodology,” 2009.

5 The Conference Board, “The Conference Board Consumer Confidence Index Declines,” November 27, 2007.

6 Yahoo! Finance, Dow Jones Industrial Average (^DJI): Historical Prices, Oct. 1, 2007–Oct. 31, 2007.

7 The Conference Board, “The Conference Board Consumer Confidence Index™ Plummets to an All-Time Low,” October 28, 2008.

8 Rasmussen Reports, “62% Say Today’s Children Will Not Be Better Off Than Their Parents,” October 3, 2009.

9 Yahoo! Finance, Dow Jones Industrial Average (^DJI): Historical Prices, Sep. 15–Oct. 31, 2008.

10 The Wall Street Journal, “The Mistakes We Make and Why We Make Them,” August 24, 2009.

11 Nofsinger, John R., Investment Madness, Prentice Hall, 2001.

12 AARP, “Why Money Worries Are Keeping Us Up at Night,” November 10, 2008.

13 The Wall Street Journal, “The Mistakes We Make and Why We Make Them,” August 24, 2009.

14 The Wall Street Journal, “The Mistakes We Make and Why We Make Them,” August 24, 2009.

15 The Wilson Quarterly, “The Traffic Guru,” Summer 2008.

16 Business Week, “When the Tulip Bubble Burst,” April 24, 2000.

17 About.com, Tax Planning: U.S., “Tax Penalty for Early Distribution of Retirement Funds,” November 3, 2008.