CHAPTER 7

Salesperson Performance: Motivating the Sales Force

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

Salespeople operate in a highly dynamic, stressful environment outside of the company. As we have already seen in Chapter 6, there are many factors that influence the salesperson’s ability to perform. One of the most critical factors is motivation. It is very important that sales managers understand the process of motivation and be able to apply it to each individual in the sales force in such a manner as to maximize his or her performance potential.

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Understand the process of motivation.

- Discuss the effect of personal characteristics on salesperson motivation.

- Understand how an individual’s career stage influences motivation.

- Discuss the effect of environmental factors on motivation.

- Discuss the effect of factors inside the company on motivation.

Unfortunately, many firms are not successful in developing systems or programs that are appropriate for the marketing challenges they face and the kinds of people they employ. Consequently, their salespeople are either undermotivated or stimulated to expend too much time and effort on the wrong tasks and activities. In either case, sales effectiveness and productivity suffer.

In view of the complicated nature of motivation and its critical role in sales management, the rest of this chapter as well as Chapter 11 (on compensation) are devoted to the subject. This chapter examines what is known about motivation as a psychological process and how a person’s motivation to perform a given job is affected by environmental, organizational, and personal variables. Chapter 11 discusses compensation plans and incentive programs sales managers use to stimulate and direct salespeople’s efforts.

THE PSYCHOLOGICAL PROCESS OF MOTIVATION

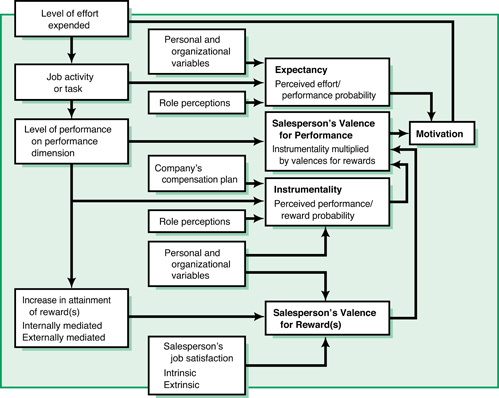

Most industrial and organizational psychologists view motivation as an individual’s choice to (1) initiate action on a certain task, (2) expend a certain amount of effort on that task, and (3) persist in expending effort over a period of time.1 For our purposes, motivation is viewed as the amount of effort the salesperson desires to expend on each activity or task associated with the job. This may include calling on potential new accounts, developing sales presentations, and managing technology. The psychological process involved in determining how much effort a salesperson will want to expend and some variables that influence the process are shown in Exhibit 7.1.

EXHIBIT 7.1

The psychological determinants of motivation

The conceptual framework outlined in Exhibit 7.1 is based on a view of motivation known as expectancy theory. A number of other theories of motivation exist,2 and many of them are useful for explaining at least a part of the motivation process. Attribution theory became widespread during the 1990s, and can be used to understand why individuals believe they have succeeded or failed at a task. Self-determination theory (SDT) assumes that humans are active organisms with innate tendency for growth, integration, and self-development, and that different contexts can either help or harm this growth and integration. We will focus on expectancy theory, which incorporates and ties together, at least implicitly, important aspects of many of those theories. It has been the subject of much empirical research in sales management, and it also provides a useful framework for guiding the many decisions managers must make when designing effective motivational programs for a sales force. Consequently, the remainder of this discussion focuses primarily on expectancy theory, although several other theories are mentioned later when we examine how personal characteristics affect the motivation of different individuals.

Major Components of the Model

The model in Exhibit 7.1 suggests that the level of effort expended by a salesperson on each job-related task will lead to some level of performance on some performance dimension. These dimensions include, for example, total sales volume, profitability of sales, and new accounts generated. It is assumed the salesperson’s performance on some of these dimensions will be evaluated by superiors and compensated with one or more rewards. These might be externally mediated rewards, like a promotion, or internally mediated rewards, such as feelings of accomplishment or personal growth.

A salesperson’s motivation to expend effort on a given task is determined by three sets of perceptions: (1) expectancies—the perceived linkages between expending more effort on a particular task and achieving improved performance; (2) instrumentalities—the perceived relationship between improved performance and the attainment of increased rewards; and (3) valence for rewards—the perceived attractiveness of the various rewards the salesperson might receive.

Expectancies—Perceived Links between Effort and Performance

Expectancies are the salesperson’s perceptions of the link between job effort and performance. Specifically, expectancy is the person’s probability estimate that expending effort on some task will lead to improved performance on a dimension. Sales managers are concerned with two aspects of their subordinates’ expectancy perceptions: magnitude and accuracy. The following statement illustrates an expectancy perception: “If I increase my calls on potential new accounts by 10 percent [effort], then there is a 50 percent chance [expectancy] that my volume of new account sales will increase by 10 percent during the next six months [performance level].” Key questions that arise from a salesperson’s expectancies and their implications for sales managers are identified in Exhibit 7.2.

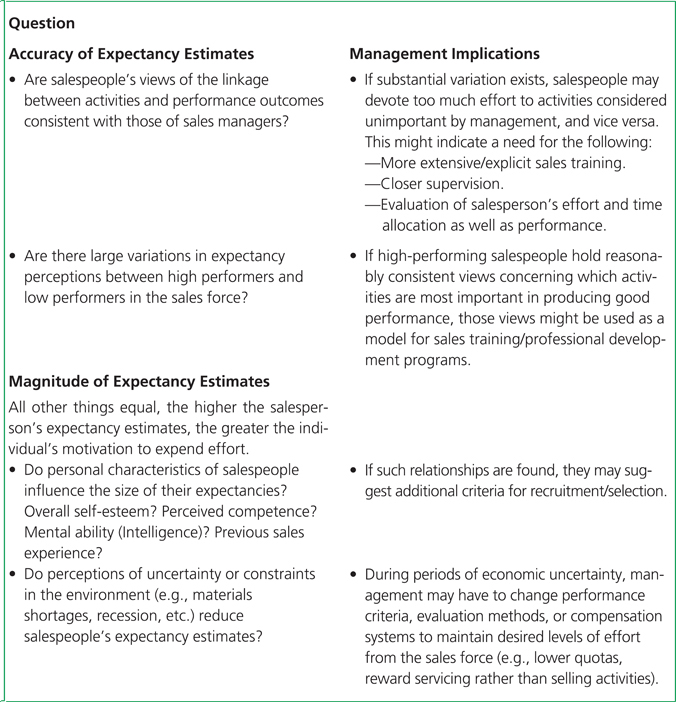

EXHIBIT 7.2

Important questions and management implications of salespeople’s expectancy estimates

Accuracy of Expectancies

The accuracy of expectancy estimates refers to how clearly the salesperson understands the relationship between effort expended on a task and the resulting achievement on some performance dimension. When salespeople’s expectancies are inaccurate, they are likely to misallocate job efforts. They spend too much time and energy on activities that have little impact on performance and not enough on activities with a greater impact. Consequently, some authorities refer to attempts to improve the accuracy of expectancy estimates as “trying to get salespeople to work smarter rather than harder.”3

Working smarter requires that the salesperson have an accurate understanding of what activities are most critical—and therefore should receive the greatest effort—for concluding a sale. Of course, a single activity might be carried out in a number of ways. For instance, a salesperson might employ any of several different sales techniques or strategies when making a sales presentation. Therefore, working smarter also requires an ability to adapt the techniques used to the needs and preferences of a given buyer.

As a result of the war on terrorism and events in the Middle East, salespeople have learned to adapt to a new selling environment. For example, due to security concerns as well as higher travel costs customers and salespeople are considering other ways of communicating with one another. As a result, presentation skills are more important than ever as Web-conferencing and teleconferencing are replacing the one-on-one presentation. As one management consultant put it, “If I do a teleconference, I’ll have to prepare much more of a presentation.” These kinds of changes have led to new skills and the reinforcement of existing ones. It is important that management motivate salespeople to expend effort on appropriate activities or approaches that can increase performance and lead to greater satisfaction within the sales force.

Unfortunately, it is possible for a salesperson to misjudge the true relationship between the effort expended on a particular task and resulting performance. When this happens, the salesperson misallocates efforts. The rep spends too much time and energy on activities that have relatively little impact on performance and not enough on activities with greater impact. Making matters even more complex, research suggests that successful salespeople can overestimate their abilities and expend too much effort attempting to close the sale. In these situations salespeople believe that with a little more effort (and resources) they will be successful.4

Research suggests that a salesperson’s immediate superior, with presumably greater knowledge and experience, will more accurately perceive the linkages between effort and performance. If this is true, then inaccurate expectancy perceptions can be improved through closer contact between salespeople and their supervisors. Expanded sales training programs, closer day-to-day supervision of the sales force, and periodic review of each salesperson’s time and effort by the supervisor should improve the accuracy of expectancy estimates.

Salespeople often complain that supervisors have an unrealistic view of conditions in the field. In addition, they do not realize what it takes to make a sale.5 If these complaints are valid, managers’ perceptions of the linkages between effort and performance may not be appropriate criteria for judging the accuracy of salespeople’s expectancies. It may be better to use the expectancy estimates of the highest performing salesperson in the company as a model for sales training and supervision.

Magnitude of Expectancies

The magnitude of expectancy estimates reflects the salesperson’s perceptions of his or her ability to control or influence his or her own job performance.

Several individual characteristics are likely to affect these expectancies. Some psychologists suggest that a salesperson’s overall level of self-esteem and perceived ability to perform necessary tasks are positively related to the magnitude of the person’s expectancy estimates.6 Similarly, the salesperson’s general intelligence and previous sales experience may influence the individual’s perceived ability to improve performance through personal efforts. If these relationships are true, they may be useful supplementary criteria for the recruitment and selection of salespeople.

Environmental characteristics also influence a salesperson’s perceptions of the linkages between effort and performance. How the salesperson perceives general economic conditions, territory potential, the strength of competition, restrictions on product availability, and so forth are all likely to affect his or her thoughts on how much sales performance can be improved by simply increasing efforts. The greater the environmental constraints a salesperson sees as restricting performance, the lower the rep’s expectancy estimates will be. Turbulence in financial markets, and fluctuations in leading global economies have created a great deal of economic uncertainty in many global markets. This has led companies to reevaluate their purchases, and consequently, salespeople are faced with a much more complex and difficult selling environment. Therefore, managers may find it desirable to change performance criteria or evaluation methods during periods of economic uncertainty to maintain desired levels of effort from the sales force.

As Exhibit 7.3 indicates, personal and organizational characteristics affect the magnitude and accuracy of salespeople’s expectancy perceptions. Managers must consider these factors when deciding on supervisory policies, compensation, and incentive plans so their subordinates’ expectancies will be as accurate as possible. The factors that affect salespeople’s expectancy estimates, along with their managerial implications, are discussed later in this chapter.

EXHIBIT 7.3

Factors influencing the motivation process

Instrumentalities—Perceived Links between Performance and Rewards

Like expectancies, instrumentalities are probability estimates made by the salesperson. They are the individual’s perceptions of the link between job performance and various rewards. Specifically, an instrumentality is a salesperson’s estimate of the probability that an improvement in performance on some dimension will lead to a specific increase in a particular reward. The reward may be more pay, winning a sales contest, or promotion. As with expectancies, sales managers should be concerned with both the magnitude and the accuracy of their subordinates’ instrumentalities.

Accuracy of Instrumentalities

The accuracy of instrumentality estimates refers to the true linkages between performance on various dimensions and the attainment of rewards as determined by management practices and policies on sales performance evaluation and rewards for levels of performance.7 Exhibit 7.4 identifies some important questions for sales management regarding a salesperson’s instrumentality estimates and their implications. These policies and practices may be misperceived by the salesperson leading the individual to concentrate on improving performance in areas that are less important to management and ultimately become disillusioned with his or her ability to attain rewards.

EXHIBIT 7.4

Important questions and management implications of salespeople’s instrumentality estimates

Thus, it is important to compare salespeople’s instrumentality perceptions with stated company policies and management perceptions of the true or desired linkages between performance and rewards. If salespeople do not accurately perceive how performance is rewarded in the firm, management must improve the accuracy of those perceptions. This is done through closer supervision and more direct feedback about evaluation and the determination of rewards.

Magnitude of Instrumentalities

One variable that has a notable impact on the magnitude of instrumentality estimates is the firm’s compensation plan. For example, a salesperson compensated largely or entirely by commission is likely to perceive a greater probability of attaining more pay by improving performance on the dimensions directly related to total sales volume (increase in total sales dollars or percentage of quota). On the other hand, the salaried salesperson is more likely to perceive a greater probability of receiving increased pay for improving performance on dimensions not directly related to short-term sales volume (new-account generation, reduction of selling expenses, or higher customer satisfaction).

The salesperson may also be rewarded with promotion, recognition, and feelings of accomplishment and may value these other rewards more highly than an increase in pay. In any case, the company’s compensation plan is unlikely to affect the salesperson’s perceptions of the linkages between performance and these nonfinancial rewards. Therefore, a compensation plan by itself is inadequate for explaining differences in motivation among salespeople.

The salesperson’s personal characteristics also influence the magnitude of instrumentality estimates. For example, the individual’s perception of whether he or she controls life’s events or whether these events are determined by external forces beyond the individual’s control. Specifically, the more salespeople believe they have internal control over their lives, the more likely they are to believe improved performance will result in the attainment of rewards.

Besides the firm’s compensation policies, other organizational factors and the personal characteristics of the salespeople can influence both the magnitude and the accuracy of their instrumentality estimates and are explored in a later section of this chapter and in Chapter 11.

Valences for Rewards

Valences for rewards are salespeople’s perceptions of the desirability of receiving increased rewards from improved performance. One question about valences that has always interested sales managers is whether there are consistent preferences among salespeople for specific kinds of rewards. Are some rewards consistently valued more highly than others?

Historically, many sales managers assume monetary rewards are the most highly valued and motivating rewards. They believe recognition and other psychological rewards are less valued and spur additional sales effort only under certain circumstances. Very little research has tested whether salespeople typically desire more pay than other rewards. Thus, the assumption is based largely on the perceptions of sales managers rather than on any evidence obtained from salespeople themselves.

There is evidence to suggest that other rewards are at least as important as financial compensation. One vice president of manufacturing for a large British based company puts it this way, “You can throw money at people—bonuses, incentives, rewards, additional skills training—and they’re all important parts of what the manager offers. But praise is number one. It goes a long way when you give them that pat on the back.” Recent research suggests that more and more companies consider other factors as or even more important than compensation. According to one sales executive, “Good management equals better performance and better motivation.” The use of cash as an incentive has actually been declining. Companies are incorporating other forms of incentives such as debit/gift cards and leisure trips.8

An even more extreme view of financial rewards argues that linking pay to performance can have a negative effect on employees’ motivation over time.9 In this view, when pay is tied to performance, employees become less interested in what they are doing and more interested in simply capturing the reward. Intrinsic motivation is eaten away by extrinsic motivators like commissions and incentive contests, and employee creativity and quality of work may suffer as a result.

In light of these contradictory arguments and research results, is the conventional wisdom that salespeople desire money more than other rewards wrong? Or do salespeople simply desire a greater variety of rewards and work-related options than individuals in other kinds of jobs? Several studies focused on business-to-business salespeople generally support the conventional view. Their findings suggest that, on average, salespeople place a higher value on receiving more pay than any other reward, including intrinsic rewards like feelings of accomplishment or opportunities for personal growth. More recently, research in a nonsales setting confirms the importance of financial incentives as the primary reward, although recognition among peers was also found to be a significant motivator.10 Informal surveys affirm that, while there are many different ways to motivate salespeople, compensation is still dominant. Overall, sales executives favor money, but offering other incentives makes sense in some cases. One high ranking sales executive summarized the view of many executives, “I’ll go with cash [as the best incentive]. People can’t always get away for trips. Besides, cash gives them a choice.”11

No universal statements can be made about what kinds of rewards are most desired by salespeople and most effective for motivating them. Salespeople’s valences for rewards are likely to be influenced by their satisfaction with the rewards they are currently receiving. Their satisfaction with current rewards, in turn, is influenced by their personal characteristics and by the compensation policies and management practices of their firm.

CAN THE MOTIVATION MODEL PREDICT SALESPERSON EFFORT AND PERFORMANCE?

Several studies have tested the ability of motivation models such as the ones outlined in Exhibits 7.1 and 7.3 to predict the amount of effort workers will expend on various job activities. The findings support the validity of such expectancy models of motivation.12

The salesperson model of performance suggests motivation is only one determinant of job performance. Thus, it seems inappropriate to use only motivation to predict differences in job performance. However, several studies have attempted to do just that, with surprising success reporting that an individual’s motivation to expend effort can explain up to 40 percent of the variation in the overall job performance.13

It is nice to know that models like Exhibit 7.1 are valid descriptions of the psychological processes that determine a salesperson’s motivation. However, there is a question of even greater relevance to sales managers as they struggle to design effective compensation and incentive programs: How are the three determinants of motivation—expectancy perceptions, instrumentality perceptions, and valences for rewards—affected by (1) differences in the personal characteristics of individuals, (2) environmental conditions, and (3) the organization’s policies and procedures? The impact of each of these variables on the determinants of motivation is now examined in greater detail.

THE IMPACT OF A SALESPERSON’S PERSONAL CHARACTERISTICS ON MOTIVATION

When placed in the same job with the same compensation and incentive programs, different salespeople are likely to be motivated to expend widely differing amounts of effort. People with different personal characteristics have divergent perceptions of the links between effort and performance (expectancies) and between performance and rewards (instrumentalities). They are also likely to have different valences for the rewards they might obtain through improved job performance. The personal characteristics that affect motivation include (1) the individual’s satisfaction with current rewards, (2) demographic variables, (3) job experience, and (4) psychological variables, particularly the salesperson’s personality traits and attributions about why performance has been good or bad. Let’s examine the impact of each of these sets of variables on salespeople’s expectancies, instrumentalities, and valences.

It should also be noted that many of these personal characteristics change and interact with one another as a salesperson moves through various career stages. For instance, when people begin their first sales job, they are likely to be relatively young and have few family responsibilities, little job experience, and low task-specific self-esteem. Later in their careers, those salespeople will be older and have more family obligations, more experience, and more self-esteem. As a result, their valences for various rewards and their expectancy and instrumentality estimates are all likely to change as their careers progress. Consequently, a later section of this chapter examines how salespeople’s motivation is likely to change during their careers and addresses some managerial implications of such changes.

Satisfaction

Is it possible to pay a salesperson too much? After a salesperson reaches a certain satisfactory level of compensation, does he or she lose interest in working to obtain still more money? Does the attainment of nonfinancial rewards similarly affect the salesperson’s desire to earn more of those rewards? The basic issues underlying these questions are whether a salesperson’s satisfaction with current rewards has any impact on the desire for more of those rewards or on different kinds of rewards. The relationship between satisfaction and the valence for rewards is different for rewards that satisfy lower-order needs (e.g., pay and job security) than for those that satisfy higher-order needs (e.g., promotions, recognition, opportunities for personal growth, self-fulfillment). Maslow’s theory of needs hierarchy,14 Herzberg’s theory of motivation,15 and Alderfer’s existence, relatedness, and growth theory16 all suggest that lower-order rewards are valued most highly by workers currently dissatisfied with their attainment of those rewards. In other words, the more dissatisfied a salesperson is with current pay, job security, and other rewards related to lower-order needs, the higher the desire to increase those rewards. In contrast, as salespeople become more satisfied with their attainment of lower-order rewards, the value of further increases in those rewards declines.

The theories of Maslow, Herzberg, and Alderfer further suggest that high-order rewards are not valued highly by salespeople until they are relatively satisfied with their low-order rewards. The greater the salesperson’s satisfaction with low-order rewards, the higher the desire for high-order rewards.

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of Maslow’s and Alderfer’s theories is the proposition that high-order rewards have increasing marginal utility. The more satisfied a salesperson is with the high-order rewards received from the job, the higher the value he or she places on further increases in those rewards.

Research in industrial psychology provides at least partial support for these suggested relationships between satisfaction and the valence of low-order and high-order rewards. Some of the evidence is equivocal, though, and some propositions—particularly the idea that high-order rewards have increasing marginal utility—have not been tested adequately.

In general, research suggests that salespeople who are relatively satisfied with their current income (a lower-order reward) have lower valences for more pay than those who are less satisfied. Most of these studies also report salespeople who are relatively satisfied with their current attainment of higher-order rewards, such as recognition and personal growth, tend to have higher valences for more of those rewards than those who are less satisfied. However, the evidence is mixed concerning whether salespeople who are relatively satisfied with their lower-order rewards have significantly higher valences for higher-order rewards than those who are less satisfied, as the theories would predict.17

Demographic Characteristics

Demographic characteristics, such as age, family size, and education, also affect a salesperson’s valence for rewards. At least part of the reason for this is that people with different characteristics tend to attain different levels of rewards and are therefore likely to have different levels of satisfaction with their current rewards. Although there is only limited empirical evidence regarding salespeople, some conclusions can be drawn from studies in other occupations.18 These conclusions are summarized in Exhibit 7.5.

EXHIBIT 7.5

The influence of demographic characteristics on valence for rewards

Generally, older, more experienced salespeople obtain higher levels of low-order rewards (e.g., higher pay, a better territory) than newer members of the sales force. Thus, it could be expected that more experienced salespeople are more satisfied with their lower-order rewards. Consequently, they should have lower valences for lower-order rewards and higher valences for higher-order rewards than younger and less experienced salespeople.

A salesperson’s satisfaction with their current level of lower-order rewards may also be influenced by the demands and responsibilities he or she must satisfy with those rewards. A salesperson with a large family to support, for instance, is less likely to be satisfied with a given level of financial compensation than a single salesperson. Consequently, the more family members a salesperson must support, the higher the valence for more lower-order rewards.

Finally, individuals with more formal education are more likely to desire opportunities for personal growth, career advancement, and self-fulfillment than those with less education. Consequently, highly educated salespeople are likely to have higher valences for higher-order rewards.

Job Experience

As people gain experience on a job, they are likely to gain a clearer idea of how expending effort on particular tasks affects performance. Experienced salespeople are also more likely to understand how their superiors evaluate performance and how particular types of performance are rewarded in the company than their inexperienced counterparts. Consequently, a positive relationship is likely between the years a salesperson has spent on the job and the accuracy of his or her expectancy and instrumentality perceptions.

In addition, the magnitude of a salesperson’s expectancy perceptions may be affected by experience. As they gain experience, salespeople have opportunities to sharpen their selling skills; and they gain confidence in their ability to perform successfully. As a result, experienced salespeople are likely to have larger expectancy estimates than inexperienced ones.19

Psychological Traits

An individual’s motivation also seems to be affected by psychological traits. Various traits can influence the magnitude and accuracy of a person’s expectancy and instrumentality estimates, as well as valences for various rewards, as summarized in Exhibit 7.6. People with strong achievement needs are likely to have higher valences for such higher-order rewards as recognition, personal growth, and feeling of accomplishment. This is particularly true when they see their jobs as being relatively difficult to perform successfully.20

EXHIBIT 7.6

The influence of psychological traits on the determinants of motivation

The degree to which individuals believe they have internal control over the events in their lives or whether those events are determined by external forces beyond their control also affects their motivation. Specifically, the more salespeople believe they have internal control over events, the more likely they are to think they can improve their performance by expending more effort. They also believe improved performance will be appropriately rewarded. Therefore, salespeople with a high internal locus of control are likely to have relatively high expectancy and instrumentality estimates.21

There is evidence that intelligence is positively related to feelings of internal control.22 Those with higher levels of intelligence—particularly, verbal intelligence—are more likely to understand their jobs and their companies’ reward policies quickly and accurately. Thus, their instrumentality and expectancy estimates are likely to be more accurate.

Finally, a worker’s general feeling of self-esteem and perceived competence and ability to perform job activities (task-specific self-esteem) are both positively related to the magnitude of expectancy estimates.23 Since such people believe they have the talents and abilities to be successful, they are likely to see a strong relationship between effort expended and good performance. Also, people with high levels of self-esteem are especially likely to attach importance to, and receive satisfaction from, good performance. Consequently, such people probably have higher valences for the higher-order, intrinsic rewards attained from successful job performance, although the lone study to examine the impact of self-esteem on salespeople’s reward valences failed to support this proposition.24

Performance Attributions

People try to identify and understand the causes of major events and outcomes in their lives. These are called performance attributions. A given individual might attribute the cause of a particular event—such as good sales performance last quarter—to the following:

- Stable internal factors that are unlikely to change much in the near future, such as personal skills and abilities.

- Unstable internal factors that may vary from time to time, such as the amount of effort expended or mood at the time.

- Stable external factors, such as the nature of the task or the competitive situation in a particular territory.

- Unstable external factors that might change next time, such as assistance from an unusually aggressive advertising campaign or good luck.

The nature of a salesperson’s recent job performance, together with the kind of causes to which the rep attributes that performance, can affect the individual’s expectancy estimates concerning the likelihood that increased effort will lead to improved performance in the future.25 Various attributions’ likely effects on the magnitude of a salesperson’s expectancy estimates are summarized in Exhibit 7.7.

EXHIBIT 7.7

The influence of performance attributions on the magnitude of a salesperson’s expectancy estimates

As Exhibit 7.7 indicates, expectancy estimates are likely to increase if recent successful sales performance is attributed to either stable or unstable internal causes or to stable external causes. For instance, salespeople are likely to attach even higher expectancies to future performance where they take credit for past success, as the result of either superior skill (stable internal cause) or personal effort (unstable internal cause). Salespeople’s expectancies are also likely to increase where past success is attributed to a perception that the task is relatively easy (stable external cause). However, if past successful performance is attributed to an unstable external cause that could change in the next performance period—such as good luck—there is no basis for salespeople to revise their expectancy estimates in any systematic way.

Suppose a salesperson performed poorly last quarter. Exhibit 7.7 indicates the impact of that poor performance on the individual’s expectancy estimates is influenced by the causal attributions of the person. If the salesperson attributes poor past performance to stable causes that cannot be changed in the foreseeable future, such as low ability (stable internal cause) or a difficult competitive environment (stable external cause), his or her expectancy estimates are likely to be lower. Interestingly, research suggests that when salespeople attribute poor performance to stable internal causes (such as low ability), they blame themselves for the failure and may seek help from others in order to improve their performance next time. However, if the poor performance is attributed to an unstable internal cause— such as not expending sufficient effort to be successful—the person’s expectancies may actually increase. The person may believe performance can be improved simply by changing the internal factor that caused the problem last time—by expending more effort.

A key to the application of attributions to performance is the accurate analysis of the salesperson’s behavior and attitudes. If, for example, the salesperson consistently blames the customer, the competition, or the economic situation for poor performance when, in fact, the poor performance is due to internal factors (lack of effort or ability), then it is unlikely the problem can be easily corrected. Fortunately, research suggests that in most cases salespeople are realistic of their assessment of the attributing success or failure to specific external and internal factors.

Management Implications

The relationships between salespeople’s personal characteristics and motivation has two broad implications for sales managers. First, people with certain characteristics are likely to understand their jobs and their companies’ policies especially well. They also perceive higher expectancy and instrumentality links. Such people should be easier to train and be motivated to expend greater effort and achieve better performance. Therefore, as researchers and managers gain a better understanding of these relationships, it may be possible to develop improved selection criteria for hiring salespeople who are easy to train and motivate.

Second, and more important, some personal characteristics are related to the kinds of rewards salespeople value. This suggests sales managers should examine the characteristics of their salespeople and attempt to determine their relative valences for various rewards when designing compensation and incentive programs. Also, as the demographic characteristics of the sales force change, a manager should be aware that salespeople’s satisfaction with rewards and their valences for future rewards might also change. There is little doubt that understanding the nature of the relationship between the salesperson’s personal characteristics and motivation is difficult and requires a unique understanding of each individual. The Leadership box highlights how important it is to understand each individual in order to maximize their motivation.

CAREER STAGES AND SALESPERSON MOTIVATION

The previous discussion of the personal factors affecting motivation also suggests that salespeople’s expectancy estimates and reward valences are likely to change as they move through different stages in their careers. As a person grows older and gains experience, demographic characteristics and financial obligations change, skills and confidence tend to improve, and the rewards he or she receives—as well as satisfaction with those rewards—are likely to change. We have seen that all of these factors can affect an individual’s expectancies and reward valences.

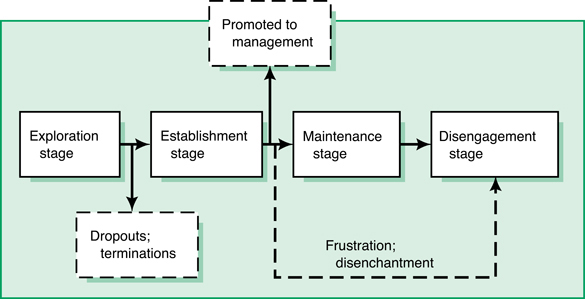

Career Stages

Research has identified four career stages through which salespeople go: exploration, establishment, maintenance, and disengagement.26 Typical paths of progression through these four career stages are diagrammed in Exhibit 7.8.

EXHIBIT 7.8

Sales career path

Exploration Stage

People in the earliest stage of their careers (typically individuals in their 20s) are often unsure about whether selling is the most appropriate occupation for them and whether they can be successful salespeople. To make matters worse, underdeveloped skills and a lack of knowledge tends to make people at this early stage among the poorest performers in the sales force. Consequently, people in the exploration stage tend to have low psychological involvement with their job and low job satisfaction. As Exhibit 7.8 indicates, this can cause some people to become discouraged and quit and others to be terminated if their performance does not improve.

Because salespeople in the exploration career stage are uncertain about their own skills and the requirements of their new jobs, they tend to have the lowest expectancy and instrumentality perceptions in a firm’s sales force. They have little confidence that expending more effort will lead to better performance or that improved performance will produce increased rewards. But they do have relatively high valences for high-order rewards, particularly for personal growth and recognition. They seek reassurance that they are making progress and will eventually be successful in their new career. Consequently, good training programs, supportive supervision, and a great deal of recognition and encouragement are useful for motivating and improving the performance of salespeople at this formative stage of their careers.

We’ve discussed sales training often throughout this chapter, often recommending good sales training as a way to spawn motivation, especially early on in a salesperson’s career. But what makes for good sales training? Because training can be very costly, firms will often opt for selective sales training, in which only a subset of salespeople receive training. When implementing this kind of training, it’s essential that managers select salespeople with diverse tenures whose functions are similar to the rest of the sales force. This will encourage spillover behaviors to those members who were not selected for training.

Establishment Stage

Those in the establishment stage—usually in their late 20s or early 30s—have settled on an occupation and desire to build it into a successful career. Thus, the major concerns of salespeople at this stage involve improving their skills and their sales performance. As they gain confidence, these people’s expectancy and instrumentality perceptions reach their highest level. People at this stage believe they will be successful if they devote sufficient effort to the job and their success will be rewarded.

Because people at this career stage are often making other important commitments in their lives—such as buying homes, marrying, and having children—their valences for increased financial rewards tend to be relatively high. However, their strong desire to be successful—and in many cases the desire to move into management—makes their valences for promotion higher at this stage than at any other. They also have very high valences for recognition and other indications that management approves of their performance and considers them worthy of promotion.

However, the strong desire for promotion at this stage can have negative consequences. As shown in Exhibit 7.8, some successful people may win promotions into sales or marketing management, but many others will not, at least not as soon as they hoped. Some of these individuals become frustrated by what they consider to be slow progress and quit for jobs in other companies that promise faster advancement or they move prematurely into a disengagement stage. To help prevent this, managers should guard against building unrealistic expectations concerning the likelihood and speed of future promotions among their establishment-stage salespeople. Research interviewing people who have left a company finds one of the most common reasons cited is dissatisfaction with career opportunities such as pay, promotion, and advancement opportunities.

Maintenance Stage

This stage normally begins in a salesperson’s late 30s or early 40s. The individual’s primary concern at the maintenance stage is with retaining the present position, status, and performance level within the sales force, all of which are likely to be quite high. For this reason, people in the maintenance stage continue to have high valences for rewards that reflect high status and good performance, such as formal recognition and the respect of their peers and superiors.

By this stage, though, both the opportunity and desire for promotion diminish. Consequently, instrumentality estimates and valences concerning promotion fall to lower levels. But salespeople at this stage often have the highest valences for increased pay and financial incentives of anyone in the sales force. Even though such people are among the highest-paid salespeople, they tend to want more money due to both increased financial obligations (e.g., children getting ready for college, large mortgages) and a desire for a symbol of success in lieu of promotion.

Disengagement Stage

At some point, everyone must begin to prepare for retirement and the possible loss of self-identity that can accompany separation from one’s job. This usually begins to happen when people reach their late 50s or early 60s. During this disengagement stage, people psychologically withdraw from their job, often seeking to maintain just an “acceptable” level of performance with a minimum amount of effort in order to spend more time developing interests outside of work. As a result, such people have little interest in attaining more high-order rewards—such as recognition, personal development, or a promotion—from their jobs. Because they tend to have fewer financial obligations at this stage, they are also relatively satisfied with their low-order rewards and have low valences for attaining more pay or other financial incentives. Not surprisingly, then, salespeople at this career stage have average performance levels lower than any others except new recruits in the exploratory stage. And their low valences for either high- or low-order rewards make it difficult to motivate them.

What is most disconcerting about disengagement, however, is that it does not occur only among salespeople at the end of their careers. As mentioned earlier, long before they approach retirement age, people may become bored with their jobs and frustrated by a failure to win promotion. Such people may psychologically withdraw from their jobs rather than search for a new position or occupation. They are commonly referred to as plateaued salespeople—people who have stopped developing, stopped improving, and often stopped showing an interest. In summary, the individual concerns, challenges, and needs associated with each career stage—together with the implications for motivating a salesperson at that stage—are presented in Exhibit 7.9.

EXHIBIT 7.9

Characteristics of different stages in a salesperson’s career

The Problem of the Plateaued Salesperson

Plateauing, or early disengagement, is not an isolated phenomenon among salespeople. Indeed, it has been suggested that 96 percent of all companies have a problem with plateaued salespeople.27 Moreover, as many as 25 percent of all salespeople operate in a comfort zone that reduces or eliminates the motivation to be a high performer.

Causes of Plateauing

The primary causes of early disengagement are the boredom and frustration that arise when a relatively young person is kept in the same job too long and sees little likelihood of a promotion or other expansion in job responsibilities in the near future. Among the reasons frequently cited for plateauing are (1) lack of a clear career path, (2) boredom, and (3) failure to manage the person effectively. It appears that the same factors hold for both men and women.

One factor, however, may be a more important cause of plateauing among saleswomen than salesmen, burnout. Although the reasons are not fully understood, it could be due to the demands of their multiple roles (mother, wife) in addition to those of their jobs. It has also been suggested the opportunity to earn high levels of pay provided by commission-based compensation systems can increase the rate of plateauing in a sales force. Managers indicate salespeople compensated by commission may more easily earn sufficient pay to meet their economic needs and thereby become less motivated by the chance to earn still higher financial compensation. We explore this issue in more detail in Chapter 11.

Possible Solutions

All of this suggests that one way of reducing the plateauing problem in a sales force—and of remotivating salespeople who have reached a plateau—is to develop clearly defined career paths for salespeople who are good performers but are not promoted into management early in their careers. Such alternative career paths typically involve promotions to positions within the sales force that involve additional responsibility and more demanding challenges.

For instance, a firm might develop a career path involving frequent promotions to increasingly lucrative and challenging territories or assignments to larger and more high-profile accounts or promote high-performing salespeople into key account management positions. The idea is to provide opportunities for frequent changes in job duties and responsibilities to increase job variety. Simultaneously, job changes can be used as rewards for good performance to motivate salespeople and show they are valued employees even though they do not move into management.

To be effective, however, promotions along the sales career path must be real and not simply changes in title. They must involve actual changes in duties and responsibilities, and be offered on the basis of good past performance.

Another closely related approach to revitalizing plateaued salespeople is to enrich their current jobs by finding ways to add variety and responsibility without developing a complicated system of hierarchical positions and promotion criteria. This is a more viable approach in smaller firms, and will probably become more popular as firms reduce the number of sales managers and adopt flatter sales force structures. For example, plateaued salespeople might be asked to devote time to training and mentoring new recruits, gathering competitive intelligence, or becoming members of cross-functional account management or product development teams. Money is often used to motivate salespeople but as the Innovation box notes, it is not always effective.

THE IMPACT OF ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITIONS ON MOTIVATION

Environmental factors such as variations in territory potential and strength of competition can constrain a salesperson’s ability to achieve high levels of performance. Such environmental constraints can cause substantial variations in performance across salespeople. In addition to placing actual constraints on performance, however, environmental conditions can affect salespeople’s perceptions of their likelihood of succeeding and thus their willingness to expend effort.

Although management can do little to change the environment faced by its salespeople (with the possible exception of rearranging sales territories), an understanding of how and why salespeople perform differently under varying environmental circumstances is useful to sales managers. Such an understanding provides clues about the compensation methods and management policies that will have the greatest impact on sales performance under specific environmental conditions.

In some industries, the pace of technological change is very rapid, and salespeople must deal with a constant flow of product innovations, modifications, and applications. Salespeople often appreciate a constantly changing product line because it adds variety to their jobs, and markets never have a chance to become saturated and stagnant. For example, it is common in the laptop computer industry to speak of product life cycles in months, not years. One leading manufacturer replaces its entire line of laptop computers every nine months. However, a rapidly changing product line can also cause problems for the salesperson. New products and services can require new selling methods and result in new expectations and demands from role partners. Consequently, an unstable product line may lead to less accurate expectancy estimates among the sales force.

In some firms, salespeople must perform in the face of output constraints, which can result from short supplies of production factors, including shortages of raw materials, plant capacity, or labor. Such constraints can cause severe problems for the salesperson. In one paper-products firm a few years ago, salespeople were penalized for exceeding quotas. In general, salespeople operating in the face of uncertain or limited product supplies are likely to feel relatively powerless to improve their performance or rewards through their own efforts. After all, their ultimate effectiveness is constrained by factors beyond their control. Therefore, their expectancy and instrumentality estimates are likely to be low.

There are many ways of assessing the strength of a firm’s competitive position in the marketplace. One might look at its market share, the quality of its products and services as perceived by customers, or its prices. Regardless of how competitive superiority is defined, though, when salespeople believe they work for a strongly competitive firm, they are more likely to think selling effort will result in successful performance. In other words, the stronger a firm’s competitive position, the higher its salespeople’s expectancy estimates are likely to be.

Sales territories often have very different potentials for future sales. These potentials are affected by many environmental factors, including economic conditions, competitors’ activities, and customer concentrations. Again, though, the salesperson’s perception of the unrealized potential of the territory can influence his or her motivation to expend selling effort. Specifically, the greater the perceived potential of a territory, the higher the salesperson’s expectancy estimates are likely to be.

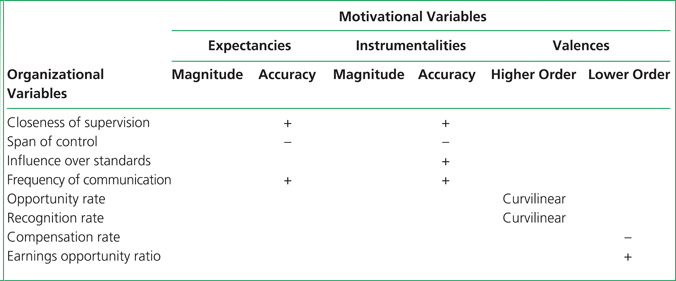

THE IMPACT OF ORGANIZATIONAL VARIABLES ON MOTIVATION

Company policies and characteristics can directly facilitate or hinder a salesperson’s effectiveness. Such organizational variables may also influence salespeople’s performance indirectly, however, by affecting their valences for company rewards and the size and accuracy of their expectancy and instrumentality estimates. Companies continue to seek new ways to connect the salesperson (or any employee) with the organization. Some such as Deloitte have asked employees to consider a spiritual connection to their work and connecting their work to the community. The goal is to create a more motivated, connected individual to the organization.28 These relationships between organizational variables and the determinants of motivation are summarized in Exhibit 7.10.

EXHIBIT 7.10

Influence of organizational variables on the determinants of motivation

Increasingly, companies are looking for ways to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of their marketing efforts. In that regard they seek to identify synergies between their brand, advertising, sales efforts, and other marketing communications. Research indicates that salespeople who identify with their company’s brand perform better; put simply, it’s helpful if the salesperson really believes in the brand. In the much the same way, salespeople who identify with a company’s advertising also are more motivated and perform better. This certainly highlights the important of creating a connection between sales and marketing.29 Additionally, it’s worth noting how motivations can be perceived by the consumer. Motivating the salesforce is a technique for producing results, often pursued in the form of inspirational appeals to the consumer. If these appeals are perceived as disingenuous, they can actually harm the salesperson’s relationship with the customer. At the end of the day, motivation is worth nothing if it’s not producing results.

Supervisory Variables and Leadership

According to one highly regarded theory of leadership, a leader attains good performance by increasing subordinates’ personal rewards from goal attainment and by making the path to those rewards easier to follow—through instructions and training, by reducing roadblocks and pitfalls, and by increasing the opportunities for personal satisfaction.30

This theory suggests that effective leaders tailor their style and approach to the needs of their subordinates and the kinds of tasks they must perform. When the subordinates’ task is well defined, routine, and repetitive, the leader should seek ways to increase the intrinsic rewards of the task. This might be accomplished by assigning subordinates a broader range of activities or by giving them more flexibility to perform tasks. When the subordinate’s job is complex and ambiguous, that person is likely to be happier and more productive when the leader provides relatively high levels of guidance and structure.

In most occupations, workers perform relatively well-defined and routine jobs, and they prefer to be relatively free from supervision. They do not like to feel their superiors “breathing down their necks.” Business-to-business salespeople, however, are different. They occupy a position at the boundary of their companies, dealing with customers and other nonorganization people who may make conflicting demands. Salespeople frequently face new, nonroutine problems. Consequently, evidence shows B2B salespeople are happier when they feel relatively closely supervised, and supportive supervision can increase their expectancy and instrumentality estimates for attaining extrinsic rewards. Closely supervised salespeople can learn more quickly what is expected of them and how they should perform their job. Consequently, such individuals should have more accurate expectancies and instrumentalities than less closely supervised salespeople. But, as we discussed, close supervision can increase role conflict since it can reduce flexibility in accommodating and adapting to customers’ demands.

Another organization variable related to the closeness of supervision is the firm’s first-level sales managers’ span of control. The more salespeople each manager must supervise (the larger the span of control), the less closely the manager can supervise each person. Therefore, the impact of span of control on role perceptions and motivation variables should be the opposite of the expected impact of close supervision, although this is changing as the result of technology.

Another related supervisory variable is the frequency with which salespeople communicate with their superiors. The greater the frequency of communication, the less role ambiguity salespeople are likely to experience and the more accurate their expectancy and instrumentality estimates should be. Again, however, frequent contact with superiors may increase the individual’s feelings of role conflict. At the same time, research suggests that salespeople who have a strong identification with their manager exhibit higher performance levels; however, over identification (the relationship between manager and salesperson becomes too close) can have a negative impact.31

Incentive and Compensation Policies

Management policies and programs concerning higher-order rewards, such as recognition and promotion, can influence the desirability of such rewards in the salesperson’s mind. For these rewards, there is likely to be a curvilinear relationship between the perceived likelihood of receiving them and the salesperson’s valence for them. For example, if a large proportion of the sales force receives some formal recognition each year, salespeople may think such recognition is too common, too easy to obtain, and not worth much. If very few members receive formal recognition, however, salespeople may believe it is not a very attractive or motivating reward simply because the odds of attaining it are so low. The same curvilinear relationship is likely to exist between the proportion of salespeople promoted into management each year (the opportunity rate) and salespeople’s desire for promotion.32

Another issue is preferential treatment for “stars.” The goal of recognition and other forms of incentives is to motivate people to do better, but what happens when one star demands and receives much more than the average or even much more than the company’s other top performers?

A company’s policies on the kinds and amounts of financial compensation paid to its salespeople are also likely to affect their motivation. As seen, when a person’s lower-order needs are satisfied, they become less important and the individual’s valence for rewards that satisfy such needs, such as pay and job security, is reduced. This suggests that in firms where the current financial compensation is relatively high, salespeople will be satisfied with their attainment of lower-order rewards. They will have lower valences for more of these rewards than people in firms where compensation is lower.

The range of financial rewards currently received by members of a sales force also might affect their valences for more financial rewards. If some salespeople receive much more money than the average, many others may feel underpaid and have high valences for more money. The ratio of the total financial compensation of the highest-paid salesperson to that of the average in a sales force is the earnings opportunity ratio. The higher this ratio is within a company, the higher the average salesperson’s valence for pay is likely to be.

Finally, the kind of reward mix offered by the firm is a factor. Reward mix is the relative emphasis placed on salary versus commissions or other incentive pay and nonfinancial rewards. It is likely to influence the salesperson’s instrumentality estimates and help determine which job activities and types of performance will receive the greatest effort from that salesperson. The question from a manager’s viewpoint is how to design an effective reward mix for directing the sales force’s efforts toward the activities believed to be most important to the overall success of the firm’s sales program. This leads to a discussion of the relative advantages and weaknesses of alternative compensation and incentive programs, the topic of Chapter 11.

SUMMARY

The amount of effort the salesperson desires to expend on each activity or task associated with the job—the individual’s motivation—can strongly influence job performance. This chapter reviewed the factors that affect an individual’s motivation level. The chapter suggested an individual’s motivation to expend effort on any particular task is a function of that person’s (1) expectancy, (2) instrumentality, and (3) valence perceptions.

Expectancy refers to the salesperson’s estimate of the probability that expending a given amount of effort on some task will lead to improved performance on some dimension. Expectancies have two dimensions that are important to sales managers—magnitude and accuracy. The magnitude of a salesperson’s expectancy perceptions indicates the degree to which the individual believes that expending effort on job activities will directly influence job performance. The accuracy of expectancy perceptions refers to how clearly the individual understands the relationship between the effort expended on a task and the performance on some specific dimension that is likely to result.

Instrumentalities are the person’s perceptions of links between job performance and various rewards. Specifically, an instrumentality is a salesperson’s estimate of the probability that a given improvement in performance on some dimension will lead to a specific increase in the amount of a particular reward. A reward can be more pay, winning a sales contest, or promotion to a better territory. As with expectancies, sales managers need to be concerned with both the magnitude and accuracy of their subordinates’ instrumentalities.

The salesperson’s valence for a specific reward is the individual’s perception of the desirability of receiving increased amounts of that reward. This valence, along with the individual’s valence for all other attractive rewards and the person’s instrumentality perceptions, determines how attractive it is to perform well on some specific dimension.

Several factors influence salespeople’s expectancy, instrumentality, and valence perceptions. Three major forces are (1) the personal characteristics of the individuals in the sales force, (2) the environmental conditions they face, and (3) the company’s own policies and procedures. The chapter reviewed some major influences and their likely impacts on each of the three categories.

KEY TERMS

Motivation

expectancies

accuracy of expectancy estimates

magnitude of expectancy estimates

instrumentalities

accuracy of instrumentality estimates

magnitude of

instrumentality estimates

valences for rewards

performance attributions (stable, unstable, internal, external)

career stages (exploration, establishment, maintenance, disengagement)

plateauing

earnings opportunity ratio

BREAKOUT QUESTIONS

- Sales support personnel include customer service reps, account coordinators, sales assistants, and others whose efforts have a critical impact on a sales force’s success. The chapter discusses motivation from the perspective of the sales force. How would you apply the concepts discussed in the chapter to sales support personnel? What can a company do to motivate sales support personnel?

- “What’s all this stuff about different pay packages and different incentive plans based on how long a sales rep has been with the company?” demanded the irate sales manager. “Around here, everybody gets the same treatment. We’re not offering customized compensation packages.” What are the problems associated with motivating sales reps on the basis of their stage in the career cycle?

- How do you motivate sales representatives when money is not effective? What can a sales manager do to motivate the successful salesperson?

- Most sales reps dislike inputting data into the company’s CRM system. They think their time could be spent more profitably, such as calling on accounts. Using Exhibit 7.3, trace the thought process sales reps go through as they consider applying more effort to putting customer data into the computer. Do the same for applying more effort to calling on accounts.

- How would you respond to a salesperson who says the following? “You are asking me to spend more time calling on new accounts, but I do not see the point in doing so; most of my business comes from my existing accounts.”

- Ethical Question. You are Vice President of Sales for a global chemical company. How would you address the concerns of Emma Smith who has asked to go to part time for the next 3 years while she takes care of new newborn child? Emma has been one of your best salespeople but would now like to work less, at least for the next few years, so she could focus on her family.

LEADERSHIP CHALLENGE: WHAT HAVE YOU DONE FOR ME LATELY?

Terri Ann Masters, Vice President of Sales for Startech Corporation, was wrestling with a critical issue related to one of her longtime and, until recently, most talented salespeople, Jason Benjamin. Startech was a French high-tech manufacturer with its corporate offices in Paris and manufacturing operation in France and China. Jason, whose territory included Silicon Valley in California, had been one of Startech’s top salespeople for 11 of his 15 years with the company. At first, Terri Ann thought it was just “bad luck” and Jason would be able to turn it around. Now, however, after four years of seeing Jason miss sales targets and hearing increasing complaints from customers, Terri Ann knew something was wrong.

This was especially critical for Startech because Jason called on some of the company’s biggest clients. Jason had worked his way up in the company and been given these accounts seven years ago. During his first three years with the accounts, Jason generated substantial new business from his clients. Management with the customers had actually gone to the trouble of calling Terri Ann and complimenting Startech on the relationship Jason had established. The end result was that Jason frequently exceeded his sales quotas and received healthy bonuses.

In the last few years, however, there was very little new business coming from Jason’s accounts. At the same time, Terri Ann knew these companies were growing and were taking business to other competitors. It was not that Jason had lost the accounts; they were still doing a reasonable business with Startech. Rather, Terri Ann recognized there was additional business the company was not getting for some reason.

Of even greater concern was the number of complaints about Jason that had been coming in to Terri Ann. Jason certainly did not have the greatest number of complaints, but given his history, they were high. In addition, Jason seemed to be less motivated. When Terri Ann would call his office on Friday afternoons, she would find that he had already left for the weekend. The “old” Jason was one of the hardest-working salespeople in the company. In addition, EU and French employment law limited Terri Ann’s flexibility in dealing with employment performance issues.

The problem was coming to a head. Management had a big push inside the company to increase productivity. Terri Ann also had several younger salespeople who were eager to move into larger, more demanding, and higher potential accounts.

Questions

- You are Terri Ann Masters. What would you do about Jason Benjamin?

- What would you do with these younger salespeople who are looking for new opportunities inside the company?

- Offer ideas on why Jason’s performance might have slipped after all these years with the company.

ROLE-PLAY: MAVEN SOFTWARE

Situation

Maven Software provides unique solutions for dental offices that want to fully integrate their patient records, billing, insurance filing, and outbound patient correspondence. Maven started out in 1987 in St. Louis as a local provider of forms utilized by doctors and dentists for record-keeping. Bob Perkins (Bob Sr.) started the firm, and when he retired in 2011 Bobby (Bob Jr.) took over as CEO. In an amazing evolution, the company has become a leading provider in the United States of integrated software solutions for dentists (they made the decision in 2005 to fully devote their efforts to that one market).

Arthur Grabber is one of the three original employees hired by Bob Sr. Arthur was the original salesperson for Maven and for years devoted his time and energy to “beating the bushes” for business—originally largely by phone and, where possible, by face-to-face sales calls. The transition to a technology product focus was a little rough for Arthur, but his relationships with key clients he developed and nurtured over many years helped him overcome the product transition. Arthur is 55 and plans to retire at age 60. Instead of being “the” salesperson for Maven, he is now one of 23 client executives who live in geographically dispersed locations throughout the United States. The sales director is a very competent woman named Leona Jones, who came to Maven in 2015 after a ten-year career in sales management with Merck.

Lately, Leona has been thinking a lot about Arthur, his history with the company, and his enormous contributions to its success over 30 years. In a way, she is in awe of his accomplishments. On the other hand, he has been rather slow to adopt technological aids to the sales process (he is reluctant to use social media as a source of client communication, for example). And she is cognizant of the fact that at this stage in Arthur’s career, piling more salary and incentive pay onto him is very unlikely to motivate him to change his basic sales approach. Don’t misunderstand—it’s not that Arthur is a “problem” salesperson; he brings in slightly better sales results annually than the average. But she would like to find a way to address his impending move from the maintenance stage to the disengagement stage of the career cycle.

She picks up the phone and calls Arthur, who is working in his in-home office in a suburb of St. Louis. She asks him to schedule a meeting to catch up on a few things related to planning business for the remainder of the year. During that meeting, she also plans to open up a nonthreatening, friendly dialogue about how Arthur would like to see his last five years with Maven unfold.

Characters in the Role-Play

Arthur Grabber, client executive for Maven Software, based in St. Louis

Leona Jones, sales director for Maven Software, based in St. Louis

Assignment

Break into pairs, with one student playing each character. The student playing Arthur simply needs to get into the character of a salesperson at his stage of the career cycle. The student playing Leona needs to develop a set of issues to bring up with Arthur about important aspects of how to enhance his productivity and satisfaction as he moves into the last few years of employment with the company. The dialogue should be positive, with the goal to come out of the meeting with some specific items for follow-up and implementation.

MINICASE: LAND ESCAPE VACATION CLUB

Land Escape Vacation Club sells fractional interests in time-share vacation properties at various beach locations. For example, an owner will purchase an interest of four weeks a year at a Land Escape property in a place like Hilton Head, South Carolina. Prospective buyers are offered a free weekend stay at a Land Escape resort if they listen to a sales presentation while they are there.

Sales at the La Jolla, California, location have been inconsistent over the past two years, and the sales manager, Denise London, has been asked by Land Escape’s vice president of sales to review the profiles of her three salespeople in order to come up with a plan to improve sales.

Catalina Curtis

Catalina is a woman in her 30s with a husband and two small children at home. She was once a television weather forecaster (she would say “meteorologist”) but got fired and was forced to do something else. She thought that working in sales would be for the short term until another television opportunity came about, but she has now been in Land Escape sales for about three years. Trying to make the best of a bad situation, she was very enthusiastic when she first began selling, but her enthusiasm and energy level have been waning as she has realized that she will probably continue doing sales for the long term. She and her husband feel some financial pressure because of their decision to put their children in private school, which is very costly. The economy has been difficult, and Catalina is beginning to believe she cannot succeed no matter what she does.

She is somewhat insecure and sensitive but conscientious and a team player. She likes people and seeks personal relationships with customers and takes a long-term approach. Her philosophy is “if potential customers don’t want to buy right away, I don’t pressure them. I will keep in contact with them and eventually they will come back and buy.” Denise does not care for Catalina’s style and tends to let her operate without supervision, because, frankly, she doesn’t know what to tell her to do better.

Zach Jones

Zach is 25 years old, just two years out of college. He has been with Land Escape for approximately eight months now. He is a perfectionist and highly competitive. Before he came to Land Escape, he had no previous sales experience, but he does have a natural selling skill. He is a little bit of a loose cannon and is not afraid to bend or even break the rules. Needless to say, he is not the least bit self-conscious. Some find him friendly and like his engaging style; however, some are turned off by it and see him as a stereotypical “slick” salesperson.

His goal is to make as much money as possible in a short amount of time. He will decide later whether he wants to stay in sales for the long term; right now he just wants to be young and have fun. He is favored by the sales manager, Denise, who sees him as a potential star because of his early success. As a result, she gives him closer supervision and guidance.

John Sargent

John is the dean of the group at age 53. He has been in Land Escape sales since its inception 12 years ago and was in sales for ten years before that time. He is good at what he does. He says, “I’ve pretty much mastered the art of time-share selling, and I’m cruising along. I know exactly how much effort to make to get the sale, so why should I do any more than that?”

His art-collecting hobby now interests him more than selling, and he has no desire to be promoted to sales manager or move to a different location. John is somewhat resentful that he has a female manager who has less experience than he does and has made it known that he needs no supervision from her. He does well enough that Denise complies and just lets him sell without a close watch.

Denise knows she needs to make some changes, but is not sure what to do. She feels the current compensation plan of 70 percent commission and 30 percent salary is fairly generous, and she even runs the occasional sales contest to boost numbers during the slower months. She had better think of something quickly before the VP gives her a “permanent vacation.”

Questions

- In what career stage would you place each of the three salespeople?

- If you were the sales manager, how would you motivate each salesperson? Explain your recommendations.

- What measures might you use to motivate them as a group?