CHAPTER 5

ARE YOU READY?

I love reading books about the fascinating new world that the future has in store for us, don’t you? My study is full of them, and Amazon.com loves me because I’m always ordering more. I’m intrigued and genuinely impressed by all the insightful predictions of how we’ll be living our lives 20 years from now. . . or 50. Flying cars! Pills to make you smarter! World peace!

One book I recently read was bold enough to describe the future 100 years from now. (I’m not so sure I’ll be around to find out if it’s accurate.)

Predicting the future is sexy. In principle, though, scenario planners shouldn’t do it. We should try to visualize what could happen and avoid acting as if we know what will happen, because, honestly, we don’t. Besides, the main value of scenario planning lies in describing a range of futures, not pointing to one particularly glamorous prognosis with a “Stand back, everybody, this is it!” mind-set.

With that caveat, this part of the book is about the future, but without the confident, absolute predictions you might find in the best sellers stacked high on my desk. Instead, I’ll highlight just a handful of trends that are going on now, all of which beg the provocative question, “Where could this lead? What kind of world could emerge if these developments continue?”

Zeroing in on the driving forces shaping our future, most trend watchers focus on the political, economic, societal, and technological (PEST) changes that are happening (or, if you recall from Chapter 2 of the book, STEBNPDILE) and how they will affect us. Instead of covering all these bases, in the next few pages I’ve selected some trends going on that may have an indirect, longer-term impact on us as people—as consumers and also as a society (the S in PEST). The P, E, and T elements of the model can wait for the sequel.

Why the focus on S? Because societal changes are the murkiest to imagine, but arguably the most far-reaching in the long term. In a sense, they are the “consequences of the consequences” of some other kind of trend.

For example, take the precipitous rise in the price of oil. That’s clearly an economic trend—and obviously a very important one. One of its many consequences (a no-brainer as far as predictions go) could be that very high gasoline prices at the pump would force middle-class consumers down a notch or two as far as their personal transportation is concerned. To ease the burden on their family budget, bigger car owners would trade in their cars for smaller, more efficient cars, and lower-income families might have to give up their cars altogether and take the bus. (We’ve seen that movie before, in fact, back in the 1970s.) So the direct economic consequence of the oil situation has to do with the car industry and public transportation, and perhaps with the growth axes of cities in the future. But one of the consequences of the consequences could also be a steadily rising resentment on the part of the new “have-nots” toward the “still-haves” who can continue to drive their luxury cars and SUVs (which are now considered ostentatious objects of derision and envy).

Resentment, envy, anger—these are attitudes that could play out in many ways, not all of them pleasant. So the rising price of oil could end up having interesting repercussions on society’s attitudes toward disparities in wealth. Ultimately, changing attitudes can have a critically important effect on consumer behavior and politics—and therefore on all kinds of companies and organizations.

The idea in these next few pages is to get you to think about these indirect connections, then look at your company and ask yourself whether you are ready.

Demographics: The War for Talent

Compared to new technologies or rapidly rising commodity prices, demographic changes are glacially slow to work their way through a population, which makes them easy for the person on the street to overlook. Yet, imperceptible as these trends may be, they potentially have a bigger and longer-lasting impact than almost any other kind of change.

A lot has been written about the aging populations in the developed world, a phenomenon that’s inexorably coming about thanks to two trends: ever lower fertility rates (i.e., fewer babies being born) and increased longevity. There are myriad consequences of the trend toward an older population, ranging from increased health care costs to a shift in Florida’s evening rush hour as retirees pile into their cars and head out en masse for their “early-bird dinners” at 4:30 in the afternoon.

Let’s focus on just one of the consequences here—the one that could have an important impact on any organization that’s concerned about its competitiveness over the next decade. (That should cover just about everybody.)

Over the past generation birthrates have been falling, so right about now, we are starting to see the effect of this trend on the labor pool in many countries, and the outlook is not very pretty. Fewer and fewer babies born, starting 20 years ago, means fewer and fewer young adults entering the workforce, starting today. Take Germany as an example. Because of the huge number of babies that were not born over the past two decades, the German labor pool is expected to shrink by a staggering 5 million people in the next 10 to 15 years. Other countries are facing a similarly dire situation.

At the same time, with more retirees leaving the labor pool to collect their pension checks, and fewer younger people entering it and paying toward the cost of those pensions, a page-one-screaming-headline type of financial crisis is looming. The countries that are at the bleeding edge of this problem may have little choice but to raise the age of retirement, increase taxes, cut pensions, cut other state-provided services—or all of these.

The mere threat of this happening has already caused rioting in Greece. But when it actually happens, some countries may become dark and nasty places in which to try to make a living. The business environment will be awful. Taxes will be high, and the underground economy will metastasize. Education and essential services may suffer from cutbacks. Social and labor unrest, unemployment, increased security issues—you name it—problems like these will be on your doorstep.

It doesn’t sound like the land of opportunity, does it? And sure enough, many younger people, especially those with an education and decent prospects in life, might pack up and leave, emigrating in search of a place where jobs are more plentiful, the streets are safer, and they, and eventually their kids, have a chance for a better future. Think it couldn’t happen? Over a million people emigrated from Russia in the past 20 years, and the bloom of Ireland’s young men and women are leaving for Britain and Australia right now. We live in a mobile world.

What does it mean for a country to be losing population like this?

For one thing, it means that competition for talent is going to heat up. In the aggregate, companies that hire young graduates are going to be facing an ever-smaller pool of candidates. Since the law of supply and demand applies to the market for talent just as it applies to any other resource, the price of talent is going to go up. Are you ready for this?

For many organizations (maybe yours, if you’re lucky), this may not be a problem. Your employment package may be so attractive that you will be turning good people away. Bully for you! But it’s a zero-sum game. The numbers are already clear: There won’t be enough talent to go around. Some companies will be winners. Some will be losers. Companies that aren’t competitive in their ability to attract, hire, and retain the talent they want will find themselves losing the war for talent. What then?

Questions:

Do you have a strategy to ensure that you are one of the winners and not one of the losers in this critical arena? Or, if you believe you can’t afford to be a winner, do you have an alternative strategy you can implement?

The economic rise of China is the big story of the past 20 years. Could China’s unexpected stagnation and decline be the big story of the next 20?

If such a scenario would come to pass, it could be because China faces two huge demographic challenges today that could undercut its ability to keep on growing before serious social problems get in the way.

The first challenge is that China’s population is aging extraordinarily quickly. Other developed countries are all aging as well, but China is undergoing a particularly speedy transformation to an old society. This is thanks to its infamous one-child population control policy, introduced at the end of the 1970s. Limiting urban couples to only one child, the policy has been very successful on its face: It has cut fertility dramatically and prevented about 300 million births over the past 30 years—the equivalent of the entire population of the United States.

But beware the law of unintended consequences, especially when it comes to social engineering! Stop 300 million people from being born, and—quelle surprise—you begin to seriously distort your population structure. China’s average age is skewing higher and higher, with the ratio of elderly dependents to people still in the labor force increasing very fast. By the year 2030, the country will actually have more dependents than children.

In China, elderly people have traditionally been taken care of by their children. But thanks to the one-child policy, people there now speak of the “4–2–1 formula”: An only child will have two parents and four grandparents to look after.

The result: China can expect many of its older people to be institutionalized. There simply won’t be enough young people to look after the older generation in the traditional way. Could this be a market opportunity? Sure. In fact, now might be a good time to invest in companies offering services aimed at assisted living for the elderly. But what will be the cost in terms of China’s social cohesion and values?

However, the looming problems of the elderly are not the only demographic challenge the country is facing. In the next decade, it could also have to deal with the even more far-reaching consequences of its second big problem, which the Chinese are calling “bare branches.”

For centuries, Chinese culture (like others in Asia) has valued girls less than boys. Particularly in rural areas, couples want a boy, who can contribute some muscle around the farm, helping to work the land with his father.

But since the advent of the one-child policy, if a couple’s first child is a girl, there is, officially, no second chance for a boy. (In certain provinces, the government magnanimously permits couples a second child if their firstborn is a girl.) For some couples, this means that if they can control the sex of their child, they will do what it takes to make sure the one child they are allowed will be a boy. And they do have control. If prenatal testing confirms that their unborn child is a girl, they can abort the baby. In extreme cases, particularly in the countryside, newborn girls may even be abandoned to die immediately after they are born, with no record made of a birth at all. In short, it is possible to ensure that you don’t have a living daughter, which leaves you free to try again for a son.

To be sure, both sex-selective abortion and infanticide are banned in China. But they happen anyway. In one survey, more than a third of the women who had had abortions admitted they did so in order to select the sex of their baby. (Read: Only girls were aborted.)

The result? China has a male-to-female sex ratio that is extraordinarily male-heavy. Countrywide, for every 100 female births reported, there are 119 male births. In some provinces this ratio is as high as 135 boys to 100 girls. No natural explanation is possible for a ratio as high as this.

If you look only at the segment of China’s population under age 20, there are 30 million more males than females. Such a huge imbalance has potentially momentous consequences for China’s future, as millions of Chinese men have no hope of being able to find a wife and start a family, at least not with a Chinese woman. It really redefines the notion of a divide between haves and have-nots.

These unlucky young men are called “bare branches” in China: They’re like the branches of a tree that will never bear fruit.

Questions:

In all of human history, there has never been a phenomenon quite like this. Where could it lead? How might Chinese society—and the government—try to remedy this situation? Through emigration? Mail-order brides? Channeling all that pent-up energy into military adventures? What kind of economic impact could this imbalance (or its solution) have? If your company does business in China, are there consequences for you?

Say good-bye to the world of cheap energy and raw materials that we’ve known and loved over the past couple of generations. Although there will be the usual ups and downs along the way, the overall trend line as the future unfolds could be one of steadily rising commodity and energy prices.

In the good old days, it was mainly supply issues and constraints that determined commodity prices. They were affected by such things as harvests and hurricanes, wars and work stoppages—events that had an impact on supply, or at least on the reliability of distribution. A few years ago, to use oil as an example, OPEC could turn the supply tap on or off, controlling oil prices fairly closely.

Supply constraints and disruptions are still important, but they’ve been overshadowed by the sheer power of demand to bid prices higher. This demand is largely the result of the emergence of a new middle class in the developing world, soon comprising about 1 billion people worldwide. India alone is expecting a dramatic surge in the size of its middle class, from 5 percent of its total population in 2005 to 41 percent in 2025—that’s an increase of 550 million new consumers. In China, the urban population will grow by nearly 300 million people between now and the year 2025, most of that being middle-class growth.

Increased urbanization and increased consumerism are the twin motors that could drive commodity price increases for many years to come. Urbanization means greater demand for infrastructure and housing, while consumerism means more demand for durable goods such as cars, refrigerators, TVs, air conditioners, and the many other energy-consuming appliances that Western households have taken for granted for years. Producing more of this infrastructure, plus all the other goodies demanded by the newly affluent, would require more steel, more copper, more rubber, more timber, more cement. . . and, of course, more energy.

Take cars, for example. China recently overtook Japan to become the world’s second-largest market (after the United States) for new cars. Over the next decade, the number of privately owned cars on the road in China is forecasted to increase from 25 to 140 million. (I calculate that to park all those 115 million new cars, you’d need a lot measuring 19 miles long by 19 miles wide.) Thomas Friedman, in his book The World Is Flat, notes that in Beijing alone, 30,000 new cars were being added to the roads each month—1,000 every day.

With more cars comes demand for more gasoline, so we can expect oil prices to increase steadily as well. Many observers think a price tag of $200 a barrel is a realistic possibility in the next few years. But even at $200, there could still be too much demand and/or too little supply.

Questions:

What could be the consequences of significantly higher oil prices? Higher inflation, as prices reflect higher transport costs? Pressure on such industries as travel and tourism? Political tensions? Or could the political will finally emerge to do what it takes to bring profitable alternative energy sources onstream more quickly?

GOBBLING UP THE WORLD’S RAW MATERIALS

China’s galloping economic growth, coupled with its rapid urbanization, could mean that the country’s ravenous hunger for building materials, energy, food, and consumer goods will continue for the foreseeable future. To put it bluntly: China could gobble up the lion’s share of the world’s basic raw materials.

According to Barclays Capital, China already consumes a quarter of the world’s copper, compared with a tenth a decade ago. It accounts for more than 90 percent of the global growth in demand for aluminum. It also accounts for about 10 percent of global oil demand, up from just 3 percent 20 years ago.

In fact, China’s appetite for these commodities is so huge that the country’s foreign policy revolves around its relentless need to secure supplies of oil and other natural resources. In 2007, China’s president Hu went on a natural resources shopping safari across the continent of Africa, resulting in such deals as a 45 percent stake in a Nigerian offshore oil block and an arrangement to mine $12 billion worth of copper ore in Congo—a sum that happens to be more than three times Congo’s annual budget.

China is also investing in oil exploration and mining opportunities in Canada, Venezuela, and Peru, and sugar refining in Australia. It lends money to Russia and Brazil in exchange for commodities it needs.

Questions:

Will China’s hunger for raw materials and agricultural commodities continue? If so, can we expect that world prices will be pushed higher and higher? Could they lock up the supply of key commodities, leaving nothing for anyone else? Money talks, but could there eventually be a political backlash to selling such huge quantities of important resources to the Chinese?

WE’RE HUNGRY!

The “next billion” also want to eat better. Rising incomes mean improving diets, especially more meat consumption. A decade from now, the world’s total meat consumption is expected to be about 65 percent higher than it was 20 years ago.

To meet the increased demand for meat and other foodstuffs, the world’s agricultural production would need to crank up significantly. But that may not be easy, for several reasons. Biofuel production (thanks to misplaced political incentives) has already shifted a good-sized portion of the world’s agricultural commodities out of the food chain and into energy production. Urbanization has also reduced available acreage in many markets, and the amount of arable land per capita is dropping. It’s not just the quantity of land that’s needed for agriculture that’s an issue; the quality of land is critical as well. If it isn’t high enough, yields may be lower. Fertilizer supplies are also a factor in production. Irrigation can be an issue as well, so water supply and prices also have to be factored in.

Meanwhile, the politicization of agricultural markets could continue. Rice is a good example. Panic over high prices in 2007 and 2008 led some countries (e.g., India, Thailand, Japan, Indonesia, Vietnam, and China) to restrict exports in an attempt to counter domestic inflation and ease potential unrest over shortages. But all this accomplished was to drive global prices even higher.

For you and me, higher food prices would be an inconvenience. But for the hundreds of millions of people in the world who already spend most of their disposable income on food, it could be a disaster. It may also be a disaster for the governments in the parts of the world where these people live, because food shortages cause instability. It was food price inflation that sparked the initial unrest in Tunisia and Egypt, for example, leading to deposed leaders within weeks.

Questions:

What other countries could be vulnerable to a rise in the price of basic foodstuffs? How could their governments react? If food prices continue to climb, could we see calls for intervention in the markets on humanitarian grounds—resulting in more artificially induced price distortion? Could biofuel subsidies be cut? What impact could that have on the price of food (and fuel)?

Our life spans are getting longer—much longer. For most of human history, people lived to the ripe old age of about 30. Globally speaking, it’s only been in the past century that our life expectancy took off. The world average in 2010 was 67.2 years, although like all averages, this figure masks some dismally low life expectancies (e.g., below 50 years in several parts of Africa).

Thanks to medical advances and healthier living, our longevity is extending. If the trend continues, some scientists think half the babies born in the developed world will live to celebrate their hundredth birthday.

Living to 100 would be great, right? Well, maybe. As Jay Leno once said, the problem with living longer is that you get those extra years when you’re in your 80s, when what you really want is some extra years when you’re in your 20s.

This trend to longer life spans will no doubt have several interesting societal consequences, some of which may already start affecting us in the next dozen years.

One of these could be that we will change the way we order, or segment, our lives. To understand what I mean, imagine that 100 years becomes a common lifespan but that nothing else changes in our lives. Say that, as now, you spend the first few years of your life in school and college, completing your formal education at age 22. Is it even conceivable that this education will still be relevant to you 60, 70, almost 80 years later?

As today, you start your professional career after the education phase is over, and retire at (let’s say) age 65. Then what? Putter around the garden, take ballroom dancing lessons, and do Sudoku for 35 years?

Looking at your career, if it, too, follows today’s normal trajectory, you would tend to stay in the same profession for the 40 or so years of your working life. If you’re good at what you do, you will rise up through the ranks of the organizations employing you, but this movement is generally upward, rarely into an entirely new field. If you start out as an architect, it would be unusual to become a corporate lawyer or high school biology teacher. If you’re trained as a cook, you will probably not switch to glassblowing or industrial design.

If then, as now, you marry at around age 27 or 28, would you and your partner really stay together for 72 years?

These notions may not make much sense in the years to come.

NEW RETIREMENT PLAN: WORK TILL YOU’RE 80

The concept of paying retirees a pension first appeared in the 1880s when Chancellor Otto von Bismarck set out to build the world’s first welfare state in newly united Germany. He introduced a tax on workers to finance a modest annuity that would allow old people a chance to decline in dignity at the end of their lives. But that was the key to this idea: The payments would ease the end of their lives. The age when the payments kicked in (initially 70, later reduced to 65) was very close to the average life expectancy.

Bismarck understood that the most logical age for retirement would be when people near the end of their productive lives. In the 1880s, this meant age 65. He could never have dreamed that pension payments might one day have to be made to retirees for 35 years.

Is the age of retirement sacrosanct? Nowadays, people are not used up at age 65—far from it. In the US Senate, for example, 39 percent of the 100 senators are over age 65. Eleven are over 75. (Sometimes it seems as if all 100 are senile, though, so maybe this is not a good group to use as an example.)

Questions:

Over the next generation, could we see our official working lives stretching from the current 40 years (age 25 to 65) to 55 or 60 years in length? This means we’d be working well into our 80s—but the age of retirement would be in line with our longer productive lives. Is this realistic from a political point of view? What if it doesn’t happen? Financially, there could be a huge shortfall as Social Security funds dry up, paying for more retirees who live longer and stay on the government’s dime much longer. Could there be a backlash against “unproductive” older people? Could retirees who elect to spend three decades dawdling about at government expense be stigmatized by society—or at least by the younger workers shouldering the financial burden? In such a case, could it be, “Farewell, class warfare; hello, generational warfare”?

BACK TO SCHOOL

As fast as our know-how is accelerating, it seems absurd to expect that an education completed when you’re in your early 20s won’t be obsolete by the time you’re 40, let alone 80. In some technical fields, what you learn in the first year of a four-year curriculum is already out of date by the time you graduate!

In the next few years, forward-thinking educators could succeed in convincing governments, teachers’ unions, and parents that our present educational model is not sustainable and begin a major overhaul of the education industry: how it’s structured; what it’s meant to achieve; and how, when, and by whom it’s delivered (more on this subject in the following pages).

Questions:

If what we learn in school is quickly outdated, how would education have to change over the next few years to ensure we don’t fall hopelessly behind? And if our working lives eventually do stretch to 55 or 60 years, could people increasingly opt to start a second career halfway through their lives—which might require a second dose of education at a point in their lives when they probably haven’t sat in a classroom for 25 years? What could be the impact on the institutions designing and delivering education? How much will be publicly owned and driven, as opposed to run by private enterprise?

MEET THE SPOUSES

What about marriage in a world of centenarians? Is it realistic to expect that someone who gets married in his or her 20s will stay with the same spouse for three-quarters of a century?

Divorce statistics sadly demonstrate that already today, a huge percentage of marriages don’t even last 15 years, let alone 75. So the short answer to the question is, “Probably no.” Could this mean that (like careers) everyone will have first, second, and third marriages?

Some will, for sure. But a number of trends are happening now that could have a significant cumulative impact on where marriage is heading as an institution. Increasing cohabitation, more children born out of wedlock, the rise of prenuptial agreements, the acceptance of same-sex marriages, and eventually, perhaps, socially sanctioned polygamy, could all bring about profound changes in marriage, family, and society.

Let’s look at the trends. First, “living together without benefit of clergy” no longer carries any societal stigma. Depending on the country, between 10 and 30 percent of couples cohabit. The concept of marriage has already been knocked off its pedestal.

A huge percentage of children are born each year to unmarried parents—as high as 50 percent in Scandinavia. In the United Kingdom, about one family out of four with dependent children is headed by a single parent. In the United States, there are over 12 million such families, and merely lamenting this fact is frowned on as politically incorrect, regarded as a misguided attempt to impose middle-class values on people who are supposedly getting along just fine, thank you very much.

Traditional ideas about how a family should be structured have gone by the wayside.

Prenuptial agreements are also changing the game. Historically, one reason the concept of marriage developed in the first place was to preserve capital within the family being created. A prenup removes this economic justification for marriage, allowing the partners to pack up and leave with what they brought into the relationship, no questions asked. These agreements are not legally enforceable everywhere yet, but the idea is catching on. In one UK survey, 46 percent of all the respondents said they would want a prenuptial agreement with their spouse-to-be, in spite of the fact that they aren’t legal there for the time being.

Admitting same-sex couples into the institution of marriage could prove to be a further step toward redefining what a family is. And the arrival in the West of more Muslim immigrants practicing polygamy could further break down resistance to the traditional idea that marriage must be between one man and one woman.

The cumulative impact of all these trends is that society could slowly scrap the idea of marriage itself as an old-fashioned relic from the past—quaint but completely unnecessary. While perhaps not completely displacing this fusty old tradition, a variety of alternative domestic arrangements, all contractually defined and legally protected as civil unions, could exist alongside it in ever greater numbers. Whether anybody calls these new arrangements “marriages” or not would be irrelevant: They would be de facto family units.

For example, if two men can marry and adopt children, thus forming a legal family, could a civil union eventually be deemed valid between two men and a woman? Or between three men and six women, for that matter? Once this barrier has been breached (and it could well be breached sometime in the next few years), unconventional communal arrangements could become very common, with adults joining by invitation, signing the papers, and becoming one of several wives or husbands in the newly extended union, or partnership—or “family,” if you prefer.

Economically, such unions could be very strong, with several breadwinners, although it may not always be easy to make group decisions on how money is spent. On the other hand, maybe a seniority system could help decision making, just as in today’s families: Mom’s and/or Dad’s vote always counts a bit more than the kids’ votes.

Speaking of kids, raising children—the other historical reason why marriage developed—would become a communal responsibility. A civil union could even recruit new wives or mothers into the partnership specifically for that role. The resulting family units would be a hybrid between a kibbutz and the kind of matriarchal commune or “line marriage” that science fiction author Robert Heinlein brilliantly described in The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress, about life on a lunar colony.

Artificial families like this could be a real boon, allowing individuals, over a period of 70 or 80 years, to find the right fit within a group, then change to a new one if and when it makes sense for them to do so, rather than being stuck with the same spouse. . . for eight long decades.

Of course, this kind of arrangement wouldn’t be for everybody. In the next decade, the vast majority of new families will probably come into being the old-fashioned way, through couples cohabiting or getting married. But a further breakdown of the perception of marriage as it has always been practiced seems to be in the cards.

Questions:

What could be the consequences for society if new kinds of unconventional family units take off? How could this change consumer attitudes and behavior? What business opportunities could it present? What new services and products might especially lend themselves to these new arrangements?

Redefining Education, One Screen at a Time

An industry that has changed very little in the past 150 years is education. How, when, and to whom education is delivered, and the building blocks of what we still call a basic education today, are ideas that were conceived during the Industrial Revolution and are still commonly used almost two centuries later. In fact, if you look only at the structure of the capstone institution of the education industry—the university—you’ll even find leftover ideas not from the 1800s, but the 1400s!

For many decades, if not centuries, education has been much the same animal, even if it has modernized in a few obvious respects. Think of the anachronism of a university laboratory outfitted with a million-dollar, state-of-the-art electron microscope, while the biology professor presiding over the lab enjoys a nineteenth-century employment perk called lifetime tenure and attends ceremonies wearing a medieval cap and gown. Tenure, by the way, is about professors pleasing their academic departments, not about pleasing their “consumers” (i.e., students). This is another way in which the university is out of synch with twenty-first-century reality.

Based on trends you can see around us right now, three key aspects of education—its cost, timing, and delivery—could change in the next decade. Since education affects literally everyone, big changes in the processes, economics, and intended outcomes of education could have a definite impact on our lives, especially on our children’s lives. What’s more, these changes could also have an impact on business, too, because they would potentially affect the quality and availability of talent. Your company’s competitiveness, not to mention the competitiveness of an entire country, could depend on how education changes in the years ahead.

IT COSTS HOW MUCH TO GO TO COLLEGE?

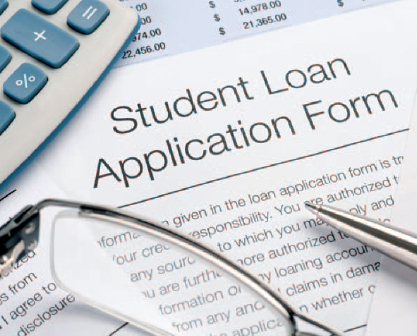

Economically, a bubble forms when the price of some asset (e.g., tulip bulbs in Holland in the 1600s or houses in America from 1998 to 2006) inflates to an artificially and unsustainably high level—higher than the intrinsic value of the asset. Speculation is usually the driving force behind this run-up in prices, but a bubble can be made a lot worse if money is artificially injected into the market, making it even easier to buy that particular asset. For example, if the government subsidizes loans aimed at making the purchase possible, then even more buyers may pile into the market and drive prices spiraling higher and higher.

Is there a higher-education bubble building in America right now? Attending college was never cheap, but in the past 20 years, it has become more and more expensive. Since the late 1970s, college tuition in America has been skyrocketing at a rate about four times faster than the increase in the consumer price index. A school that charged $4,000 a year in tuition and fees a generation ago now costs more than $40,000 a year to attend.

How did this happen? The answer is simple: the Feds. In order to make a university education affordable to everyone (in theory a laudable goal) the US government lends money at preferential rates to students so they can buy a high-priced education. Channeled through these student loans, almost $100 billion in tax money is redistributed into the US education market each year.

Convinced they need a college education to get ahead (“It’s the key to success!”), more students borrow more money, which inevitably results in price inflation. The schools simply raise their fees to soak up as much of this money as they can. Who can blame them? There’s nothing to put any downward pressure on their tuition at all: no real price competition between schools, no regulatory bodies to keep prices in line. It’s like a license to print money.

Some of these funds are put to excellent use, of course. Electron microscopes are not cheap, last time I looked. But the schools also spend a lot of the money they take in on bloated administrative staffs, expensive athletics programs, and, increasingly, on amenities such as luxury housing, gourmet dorm food, and climbing walls. These may help the schools from a marketing standpoint, but they don’t add much to the quality of the actual education product.

Is the current trend sustainable? The recent economic downturn may be bringing this all to a halt—or at least to the point where some students and their parents are seriously rethinking the value of the education they should go into debt to pay for. Many new graduates leave school owing thousands of dollars to the federal government, yet they are unable to land a job that pays enough to allow them to pay off their debt. Suddenly, the return on investment (ROI) on their education is starting to look a lot different.

With certain degrees (e.g., engineering or computer sciences), graduates have a decent chance of landing a job that pays well. For them, the ROI on their education is acceptable, at least for the time being. However, if university fees continue to outpace salary growth, the ROI calculation even for fairly lucrative career paths will look worse and worse.

Not everyone goes to college to become an engineer or programmer, though. What if you want to major in nineteenth-century French literature, or to get a degree in some recently invented field such as cult film studies? Is it worthwhile to borrow heavily and spend perhaps $150,000 over four years (let’s say four and a half years) only to end up with a degree that doesn’t qualify you for work in a field paying a decent salary—or perhaps any field at all?

There’s nothing wrong with getting a degree in basket weaving management or Latin American feminist studies. Then again, if it costs so much, is it economically intelligent? Far from liberating graduates to take wing in the grown-up world, a degree in a field with no marketability becomes a ball and chain that weighs them down instead. This realization is fueling the current protests on Wall Street, and could lead to a change in how higher education is priced, or paid for.

Questions:

Could students and their parents become more consumer-driven in their choice of higher education? Could price competition become a reality that universities would have to contend with? We should also remember that there’s another factor at play here, too: demographics. The pool of young people (i.e., the prospective market for universities) is not growing, but rather shrinking. Faced with an ever-smaller number of 18-year-olds who are less and less willing to undertake the huge financial investment required, could tuition levels actually collapse? After all, that’s the classic final phase of a bubble, when everyone bails out. If this happens, how would schools react? Would they cut back on their noncore activities? Would they emerge as different kinds of institutions than they are today? What might be the impact on the education offered?

THREE ALMA MATERS?

The next big change in education could have to do with the timing of its delivery. The way the industry’s model works today, most of us are in the education pipeline from the time we’re 5 until we’re either 18 (high school), 22 (undergraduate university), or perhaps 25 or 26 (graduate school), give or take a year or so. This education is then supposed to last us the rest of our lives. Later in our lives, we may go on for some continuing education courses that last anywhere from a day or two to several weeks of seminars or courses that are usually work-related and paid for by our employer.

This model is becoming obsolete, fast. As mentioned earlier, our working lives are going to be longer, and could eventually span more than 60 years. Would people want to stay in a single career track that long? They may decide to fill those 60 years with three separate careers—for example a first, main career lasting 25 years (until about age 50), after which they embark on a second career for 10 or 15 more years, and finally another one taking them up to retirement at age 80 or even later. Another realistic scenario is that, along the way, they lose a job and decide to take advantage of the opportunity to make a career switch into something new.

Rapid obsolescence of what’s taught in schools is, of course, another issue, as I’ve already mentioned. Taking these two points together, can an education, virtually all of which is delivered to you by the time you’re 25, serve you until you’re 80 or 90 years old?

Questions:

In the near future, could we receive not an education, but rather two or three educations? How might the first of these rounds of education (the one we get when we’re still young) change ? What might a second or third education look like, assuming we partake of it while we are adults with other responsibilities? How much would it cost, and who would pay? How would society change if people made intensive forays back into the education pipeline as adults?

COMING SOON TO A SCREEN NEAR YOU

Distance learning is not new. Such well-known distance providers as Open University in the United Kingdom and the University of Phoenix in the United States offer accredited degrees that are delivered completely, or mostly, online. They have already been around for a few years and attract thousands of fee-paying students each year.

There’s the rub: They still charge fees. However, you can take practically any Massachusetts Institute of Technology course online for free. One of the world’s top universities, MIT decided in 2002 to put its courses, lecture notes, and educational materials on the Internet, available to anyone. The program is called MIT Open CourseWare (OCW).

Meanwhile, a virtual one-man-band of a university called the Khan Academy, operating since 2009, has created more than 2,600 video tutorials that are all available on YouTube. Covering a huge range of topics in math, science, economics, and finance, these 10-minute videos have generated almost 70 million views as of October 2011. And, of course, being on YouTube, they’re free of charge as well.

MIT and the Khan Academy are pioneers. They also have funding for their ventures, which is obviously important if their content is to be offered without charging for it. MIT, for example, sinks $3.5 million a year into running OCW. Could other Khan Academies spring up over the next few years? If they do, the education industry may never be the same.

Why? Would these service providers spell the end of brick-and-mortar schools and universities? That’s very doubtful. In the future, face-to-face learning will surely remain as important as ever, and schools will continue to provide this. But the flexible, quickly developing online programs could have a powerful influence on how teachers teach and how students learn—on the entire experience, from curriculum development and lesson planning to classroom discussion and interaction, even homework assignments.

For example, some teachers are already using Khan Academy tutorials to complement their own work, and they’ve established an innovative twist: The students watch the Khan tutorial (i.e., the lecture) on their own time at home, then do the “homework” exercises the next day in the classroom, with the teacher floating among them to give a helping hand where needed. In other words, the videos have flipped the conventional classroom experience on its head.

Questions:

Could public education head in this direction? Is there any reason why the tax money that funds public schools couldn’t be used to develop a parallel Khan-like delivery system to complement in-class learning? How could that change the staffing and facilities at conventional schools?

Could Khan Academy–type tutorials make career switching easier? If gaining the necessary skill set for a new career doesn’t entail huge costs in terms of money or time, could this new mode of delivery facilitate a trend toward three-career lives? Meanwhile, could online education pose a threat to the ability of brick-and-mortar schools to keep charging high tuition fees in the future? As more “education consumers” turn to these alternatives, could competition drive tuition fees lower at fee-charging universities? What happens to these schools when their revenue streams diminish?

Right now, a disadvantage of the Khan Academy–type alternative is that it isn’t accredited and therefore can’t offer an actual degree. How long will this remain the case? Or, perhaps a better question is, how long will this remain important? In the future, will knowledge trump credentials?

Web 9.0: How Will It Change Us?

In the past 15 years, the Internet has changed the world as dramatically as did gunpowder or movable type. But unlike these other two inventions, the Internet will continue to develop over the years, so the myriad changes it can potentially bring about are far from over.

How might the business landscape, our jobs, our lives, and—okay, let’s be dramatic—the whole world be different a decade from now, thanks to the Web?

Even if it isn’t easy for a tech nullity like myself to imagine all the things it may be able to do, it’s worth reflecting about the future consequences of the Internet. Because what it will do is certainly intriguing, but perhaps even more interesting is what it could do to us. How might the Web continue to change the way we live and work?

SCHOOL? THERE’S AN APP FOR THAT

In a decade, most of the people on the planet could own handheld devices that give instantaneous access to 99.9 percent of the world’s accumulated knowledge. Actually, this device already exists, and you probably have one in your pocket right now. But future smartphones could be faster, cheaper, more user-friendly, and have an interface that facilitates the only tricky part of accessing all that information: asking the right questions.

Questions:

Can there be any doubt that handheld devices accessing the Web will also play a decisive role in the future of education? When every eight-year-old has such a smartphone, how could education change? Will we feel the need to teach things to children that everyone knows they could simply look up, anytime, anywhere? Do students need to know the content of the Constitution of the United States or that the Battle of Waterloo took place in 1815 when Wikipedia and a thousand other sites are accessible 24/7 on the gizmos they carry around (also 24/7)? Or could a large part of education center on teaching kids how to use this magnificent tool? It’s a safe prediction that the Web (or rather, Web plus mobile device) will change education. But how could it change children—and childhood?

THE GLOBALIZATION OF EVERYTHING AND EVERYONE

It’s not just big companies that move jobs offshore. Even at the individual level, the Internet allows us to globalize our networks, teams, and communities—to the possible detriment of local alternatives. I myself send work offshore to talented people I know in Austin, Zurich, and Belfast; for example, I collaborate online with a publisher in Maastricht, and my website 11changes.com was designed for me by developers in Mexico City whom I’ve never even met. I’m a one-man global conglomerate! You probably are, too.

Questions:

What impact could this trend have on your ability to create, compete, and react? Will far-flung dream teams take the place of equally capable people right here under your nose? Could the Web be helping you get the best talent in the world, yet also causing you to overlook talent just down the hall?

DISINTERMEDIATION OR MOTIVATION?

When was the last time you went to a travel agent to book a flight? When did you last walk into a bank and deal face-to-face with a teller? For that matter, when was the last time you went to a bookstore to buy a book? The Internet has enabled us to avail ourselves of a huge array of products and services directly, without much need for, or contact with, human intermediaries.

Cutting out the middle layer works in both directions, too: For example, while we consumers can go online to buy an MP3 version of a song, thus bypassing the music store, musicians can record songs and sell the MP3 to fans online, thus bypassing the record label. Both parties (consumers and producers) can develop strategies to use the Web to cut out the intermediaries they traditionally had to deal with.

Travel agents, bookstores, and bank tellers may all still exist in the physical world a decade from now, but if they do, could their roles need a rethink? In a world where people prefer to hop online and buy airline tickets or books directly, these people will need to add value—enough value that customers will be willing to pay more than they do online for the same product or service. Call the price difference a “human interface fee.” How many people would be willing to pay this fee?

Questions:

Is the Web a fundamentally deflationary instrument, always steering buyers to the lowest prices and thus forcing prices down across the board? Or could this transparency prove to be the driving force behind a parallel development—namely, the flourishing of a service culture? If you’re a seller and you know you don’t offer the lowest price (which the Web can easily confirm), would you feel compelled to build up some other aspect of your offer so you would be competitive? Could this aspect be good old-fashioned human service?

PRIVACY: AN OUTDATED NOTION

Privacy is another concept that is being reshaped by the Internet. For example, here in Switzerland, Google Street View is required to obscure practically anything that could help to identify individuals inadvertently caught by its 360-degree cameras: not just faces and car license plate numbers, but even skin color and clothing. In Germany, residents can insist that Google blur images of their houses. Meanwhile, in Japan recently, a woman sued Google because her underwear was visible on Street View, hanging on a clothesline for all the world to see. (Sounds like a bunch of old fuddy-duddies to me.)

However, consider the other end of the spectrum. Teenagers seem only too happy to disclose an astonishing amount of information about themselves online. Instead of risks, they see benefits in sharing photos and personal information about themselves. Sharing helps them establish friendships and build communities.

Questions:

As Facebook-addicted Gen Yers grow older, could their idea of privacy (or rather, nonprivacy) become the norm in society? Could the value of being part of an open community be regarded as greater than the value of being sure that no one can see what your house (or underwear) looks like?

Or, once they’ve grown up and acquired some assets worth protecting, could Gen Y revert to more conventional ideas about which information to share and which to keep private?

7 BILLION EYEWITNESSES

Imagine you’re an evil dictator (it’s easy if you try). One day a riot breaks out in the capital, and your troops start shooting protestors. When that happens, your regime’s worst enemies are not the demonstrators but Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube. With their ability to zap eyewitness reports worldwide in seconds, these tools are very dangerous to you and your regime. They’re perfect for stirring up reactions against you around the world, not to mention facilitating actual revolution by helping to direct and coordinate the mob in the streets.

Questions:

How might dictators fight back? Could they throw the switch and turn off the Internet? Could tweeting become a criminal act? Could the shock troops be ordered to go after anyone seen filming? More broadly, how could social media shape the future of political activism? If applying “Twitter pressure” to entrenched institutions can bring down authoritarian governments in Tunisia and Algeria, is it imaginable that their power could also help bring about the end of something much more benign—for example, the monarchy in the United Kingdom? What might have happened to Queen Elizabeth if Twitter had existed when Princess Diana died? Steered in just the right way, could social media bring people out on the streets to protest and fight. . . anything?

FACTS VERSUS OPINIONS

When I was growing up in the 1970s, my personal sources of information about what was going on in the world were the hometown newspaper, the CBS Evening News (God bless you, Walter Cronkite), a weekly flip through Time magazine, and the occasional three-minute news bulletin on the radio. At the time, these sources seemed to me to be utterly factual, utterly neutral, utterly trustworthy.

Today I get almost all my news online, and probably 80 percent of that is filtered through blogs. In other words, I’m often exposed to opinions about the news before I read the news itself. Sometimes I don’t even have to get the facts; I’m more interested in the opinions about the facts.

Since the Web became interactive a few years ago, it’s much more a medium of opinions than facts. (That’s my opinion anyway.) Blogs, comments, flame wars, ratings, and reviews: The Web provides everyone a platform to opine, argue, hurl epithets, complain, urge, provoke, pontificate.

Where could this trend lead? Already, consumer reviews about a product are considered much more reliable than information published by the product’s manufacturer. About half of all buyers consider opinions shared on their networks before making a purchase. According to one survey, 90 percent of consumers trust online recommendations from people they know—and 70 percent from people they don’t know! In short, advice and opinions are sought out on the Web, and for the most part, they’re trusted.

Questions:

When we all have the mobile devices I mentioned earlier, is it conceivable that a huge amount of our time will be spent accessing, digesting, and contributing to the ceaseless flow of opinions on the Web—recording our reactions to everything, documenting them with photos and videos, and dumping them into the maw of the Internet for the edification of our followers? Could there be an impact on business relationships? For example, could a hotel offer me a lower rate if I promise to post a positive review? Could I threaten to post a bad review unless I’m offered a discount? What happens to society when everyone has this power? Exposed to online opinions hundreds of times a day, might we learn to shut it all out and stop believing anything that anyone says about anything? How could this lack of trust change marketing, for example? Do we face a future of nothing but bitter cynicism and bad reviews?

FINDING MR. RIGHT

Depending on the source of the statistics, between 15 and 45 percent of newly married couples in the United States met online. In other countries, the figure appears to be between 5 and 10 percent, trending upward.

Questions:

What could be the consequences of this trend a decade from now? Could divorce rates be lower? After all, couples who meet online have already filled in the form, so to speak, and established their compatibility in a range of potentially touchy areas before even meeting for that first glass of chardonnay. They’ve vetted one another. Logically, this could mean that their marriages will be stronger.

Or could just the opposite be true? People are not logical; they’re unpredictable. Sharing mutual interests is no guarantee that a relationship will last. If the thrill is gone, it’s gone, even if you both adore Thai food, John Irving novels, and Earth, Wind & Fire. The Web makes it easier to look for a new partner. You could even be sifting through profiles online in the den while your spouse is in the living room watching TV. Could the Web therefore be a contributing factor to an increase in the divorce rate? By facilitating the possibility of moving on to greener pastures, could the Web turn us all into impatient perfectionists?