Chapter 11. Information Security Incident Management

Chapter Objectives

After reading this chapter and completing the exercises, you will be able to do the following:

![]() Prepare for an information security incident.

Prepare for an information security incident.

![]() Identify an information security incident.

Identify an information security incident.

![]() Recognize the stages in incident management.

Recognize the stages in incident management.

![]() Properly document an information security incident.

Properly document an information security incident.

![]() Understand federal and state data breach notification requirements.

Understand federal and state data breach notification requirements.

![]() Consider an incident from the perspective of the victim.

Consider an incident from the perspective of the victim.

![]() Create policies related to information security incident management.

Create policies related to information security incident management.

Incidents happen. Security-related incidents have become not only more numerous and diverse but also more damaging and disruptive. A single incident can cause the demise of an entire organization. In general terms, incident management is defined as a predicable response to damaging situations. It is vital that organizations have the practiced capability to respond quickly, minimize harm, comply with breach-related state laws and federal regulations, and maintain their composure in the face of an unsettling and unpleasant experience.

Organizational Incident Response

Incidents drain resources, can be very expensive, and divert attention from the business of doing business. Keeping the number of incidents as low as possible should be an organization priority. That means as much as possible identifying and remediating weaknesses and vulnerabilities before they are exploited. As we discussed in Chapter 4, “Governance and Risk Management,” a sound approach to improving an organizational security posture and preventing incidents is to conduct periodic risk assessments of systems and applications. These assessments should determine what risks are posed by combinations of threats, threat sources, and vulnerabilities. Risks can be mitigated, transferred, or avoided until a reasonable overall level of acceptable risk is reached. That said, it is important to realize that users will make mistakes, external events may be out of an organization’s control, and malicious intruders are motivated. Unfortunately, even the best prevention strategy isn’t always enough, which is why preparation is key.

Incident preparedness includes having policies, strategies, plans, and procedures. Organizations should create written guidelines, have supporting documentation prepared, train personnel, and engage in mock exercises. An actual incident is not the time to learn. Incident handlers must act quickly and make far-reaching decisions—often while dealing with uncertainty and incomplete information. They are under a great deal of stress. The more prepared they are, the better the chance that sound decisions will be made.

The benefits of having a practiced incident response capability include the following:

![]() Calm and systematic response

Calm and systematic response

![]() Minimization of loss or damage

Minimization of loss or damage

![]() Protection of affected parties

Protection of affected parties

![]() Compliance with laws and regulations

Compliance with laws and regulations

![]() Preservation of evidence

Preservation of evidence

![]() Integration of lessons learned

Integration of lessons learned

![]() Lower future risk and exposure

Lower future risk and exposure

What Is an Incident?

An information security incident is an adverse event that threatens business security and/or disrupts service. Sometimes confused with a disaster, an information security incident is related to loss of confidentiality, integrity, or availability (CIA) (whereas a disaster is an event that results in widespread damage or destruction, loss of life, or drastic change to the environment). Examples of incidents include exposure of or modification of legally protected data, unauthorized access to intellectual property, or disruption of internal or external services. The starting point of incident management is to create an organization-specific definition of the term incident so that the scope of the term is clear. Declaration of an incident should trigger a mandatory response process. The definition and criteria should be codified in policy. Incident management extends to third-party environments. As we discussed in Chapter 8, “Communications and Operations Security,” business partners and vendors should be contractually obligated to notify the organization if there is an actual or suspected incident.

Although any number of events could result in an incident, a core group of attacks or situations are most common. Every organization should understand and be prepared to respond to intentional unauthorized access, distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks, malicious code (malware), and inappropriate usage.

Intentional Unauthorized Access or Use

An intentional unauthorized access incident occurs when an insider or intruder gains logical or physical access without permission to a network, system, application, data, or other resource. Intentional unauthorized access is typically gained through the exploitation of operating system or application vulnerabilities using malware or other targeted exploit, the acquisition of usernames and passwords, the physical acquisition of a device, or social engineering. Attackers may acquire limited access through one vector and use that access to move to the next level.

Denial of Service (DoS) Attacks

A denial of service (DoS) attack is an attack that successfully prevents or impairs the normal authorized functionality of networks, systems, or applications by exhausting resources or in some way obstructs or overloads the communication channel. This attack may be directed at the organization or may be consuming resources as an unauthorized participant in a DoS attack. DoS attacks have become an increasingly severe threat, and the lack of availability of computing and network services now translates to significant disruption and major financial loss.

Note

Malware

Malware has become the tool of choice for cybercriminals, hackers, and hacktivists. Malware (malicious software) refers to code that is covertly inserted into another program with the intent of gaining unauthorized access, obtaining confidential information, disrupting operations, destroying data, or in some manner compromising the security or integrity of the victim’s data or system. Malware is designed to function without the system’s user knowledge There are multiple categories of malware, including virus, worm, Trojans, bots, ransomware, rootkits, and spyware/adware. Suspicion of or evidence of malware infection should be considered an incident. Malware that has been successfully quarantined by antivirus software should not be considered an incident.

Note

Inappropriate Usage

An inappropriate usage incident occurs when an authorized user performs actions that violate internal policy, agreement, law, or regulation. Inappropriate usage can be internal facing, such as accessing data when there is clearly not a “need to know.” An example would be when an employee or contractor views a patient’s medical records or a bank customer’s financial records purely for curiosity’s sake, or when the employee or contractor shares information with unauthorized users. Conversely, the perpetrator can be an insider and the victim can be a third party (for example, the downloading of music or video in violation of copyright laws).

Incident Severity Levels

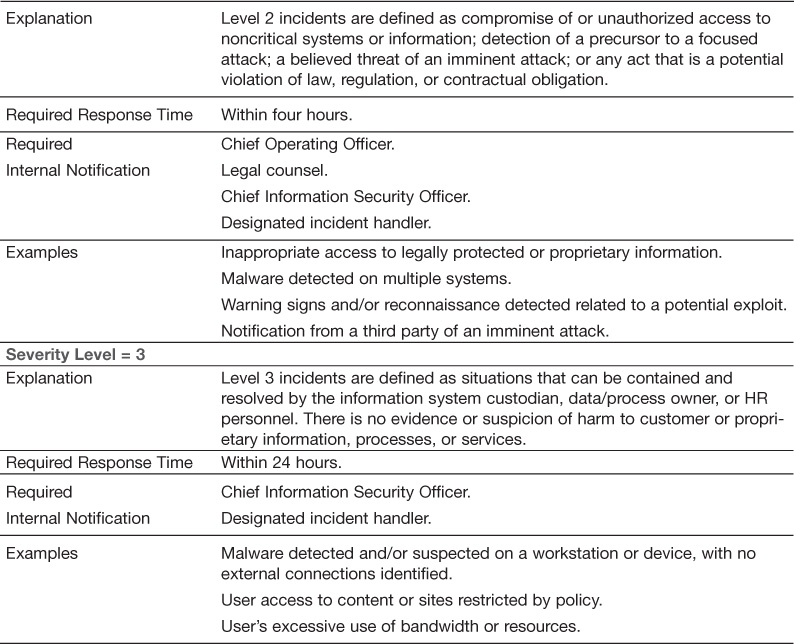

Not all incidents are equal in severity. Included in the incident definition should be severity levels based on the operational, reputational, and legal impact to the organization. Corresponding to the level should be required response times as well as minimum standards for internal notification. Table 11.1 illustrates this concept.

How Are Incidents Reported?

Incident reporting is best accomplished by implementing simple, easy-to-use mechanisms that can be used by all employees to report the discovery of an incident. Employees should be required to report all actual and suspected incidents. They should not be expected to assign a severity level, because the person who discovers an incident may not have the skill, knowledge, or training to properly assess the impact of the situation.

People frequently fail to report potential incidents because they are afraid of being wrong and looking foolish, they do not want to be seen as a complainer or whistleblower, or they simply don’t care enough and would prefer not to get involved. These objections must be countered by encouragement from management. Employees must be assured that even if they were to report a perceived incident that ended up being a false positive, they would not be ridiculed or met with annoyance. On the contrary, their willingness to get involved for the greater good of the company is exactly the type of behavior the company needs! They should be supported for their efforts and made to feel valued and appreciated for doing the right thing.

What Is an Incident Response Program?

An incident response program is composed of policies, plans, procedures, and people. Incident response policies codify management directives. Incident response plans (IRPs) provide a well-defined, consistent, and organized approach for handling internal incidents as well as taking appropriate action when an external incident is traced back to the organization. Incident response procedures are detailed steps needed to implement the plan.

An incident response plan (IRP) is a roadmap, guidance, and instructions related to preparation, detection and analysis, initial response, containment, eradication and recovery, notification closure and post-incident activity, and documentation and evidence-handling requirements. Although described in a linear fashion, these activities often happen in parallel:

![]() Preparation includes developing internal incident response capabilities, establishing external contracts and relationships, defining legal and regulatory requirements, training personnel, and testing plans and procedures.

Preparation includes developing internal incident response capabilities, establishing external contracts and relationships, defining legal and regulatory requirements, training personnel, and testing plans and procedures.

![]() Detection and investigation include establishing processes and a knowledge base to accurately detect and assess precursors and indicators. A precursor is a signal or warning that an incident may occur in the future. An indicator is substantive or corroborating evidence that an incident may have occurred or may be occurring now. Indicators are sometimes referred to as IOCs (indicators of compromise).

Detection and investigation include establishing processes and a knowledge base to accurately detect and assess precursors and indicators. A precursor is a signal or warning that an incident may occur in the future. An indicator is substantive or corroborating evidence that an incident may have occurred or may be occurring now. Indicators are sometimes referred to as IOCs (indicators of compromise).

![]() Initial response include incident declaration, internal notification, activation of an incident response team, and/or designated incident handlers, and prioritization of response activities.

Initial response include incident declaration, internal notification, activation of an incident response team, and/or designated incident handlers, and prioritization of response activities.

![]() Containment includes taking the steps necessary to prevent the incident from spreading, and as much as possible limit the potential for further damage.

Containment includes taking the steps necessary to prevent the incident from spreading, and as much as possible limit the potential for further damage.

![]() Eradication and recovery include the elimination of the components of the incident (for example, malicious code, compromised passwords), addressing the vulnerabilities related to the exploit or compromise, and restoring normal operations.

Eradication and recovery include the elimination of the components of the incident (for example, malicious code, compromised passwords), addressing the vulnerabilities related to the exploit or compromise, and restoring normal operations.

![]() Notification includes the steps taken to notify state and federal agencies, affected parties, victims, and the public-at-large.

Notification includes the steps taken to notify state and federal agencies, affected parties, victims, and the public-at-large.

![]() Closure and post-incident activity include incident recap, information sharing, documentation of “lessons learned,” plan and procedure updates, and policy updates and risk reviews, as applicable.

Closure and post-incident activity include incident recap, information sharing, documentation of “lessons learned,” plan and procedure updates, and policy updates and risk reviews, as applicable.

![]() Documentation and evidence-handling requirements include the recording of facts, observations, participants, actions taken, forensic analysis, and evidence chain of custody. Although the primary reason for gathering evidence during an incident is to resolve the incident, it may also be needed for subsequent risk assessments, notifications, and legal proceedings.

Documentation and evidence-handling requirements include the recording of facts, observations, participants, actions taken, forensic analysis, and evidence chain of custody. Although the primary reason for gathering evidence during an incident is to resolve the incident, it may also be needed for subsequent risk assessments, notifications, and legal proceedings.

Key Incident Management Personnel

Key incident management personnel include incident response coordinators, designated incident handlers, incident response team members, and external advisors. In various organizations, they may have different titles but the roles are essentially the same.

The incident response coordinator (IRC) is the central point of contact for all incidents. Incident reports are directed to the IRC. The IRC verifies and logs the incident. Based on predefined criteria, the IRC notifies appropriate personnel, including the designated incident handler (DIH). The IRC is a member of the incident response team (IRT) and is responsible for maintaining all non-evidence-based incident-related documentation.

Designated incident handlers (DIHs) are senior-level personnel who have the crisis management and communication skills, experience, knowledge, and stamina to manage an incident. DIHs are responsible for three critical tasks: incident declaration, liaison with executive management, and managing the incident response team (IRT).

The incident response team (IRT) is a carefully selected and well-trained team of professionals that provides services throughout the incident lifecycle. Depending on the size of the organization, there may be a single team or multiple teams, each with their own specialty. The IRT members generally represent a cross-section of functional areas, including senior management, information security, information technology (IT), operations, legal, compliance, HR, public affairs and media relations, customer service, and physical security. Some members may be expected to participate in every response effort, whereas others (such as compliance) may restrict involvement to relevant events. The team as directed by the DIH is responsible for further analysis, evidence handling and documentation, containment, eradication and recovery, notification (as required), and post-incident activities.

Tasks assigned to the IRT include but are not limited to the following:

![]() Overall management of the incident

Overall management of the incident

![]() Triage and impact analysis to determine the extent of the situation

Triage and impact analysis to determine the extent of the situation

![]() Development and implementation of containment and eradication strategies

Development and implementation of containment and eradication strategies

![]() Compliance with government and/or other regulations

Compliance with government and/or other regulations

![]() Communication and follow-up with affected parties and/or individuals

Communication and follow-up with affected parties and/or individuals

![]() Communication and follow-up with other external parties, including the Board of Directors, business partners, government regulators (including federal, state, and other administrators), law enforcement, representatives of the media, and so on, as needed

Communication and follow-up with other external parties, including the Board of Directors, business partners, government regulators (including federal, state, and other administrators), law enforcement, representatives of the media, and so on, as needed

![]() Root cause analysis and lessons learned

Root cause analysis and lessons learned

![]() Revision of policies/procedures necessary to prevent any recurrence of the incident

Revision of policies/procedures necessary to prevent any recurrence of the incident

Figure 11.1 illustrates the incident response roles and responsibilities.

Communicating Incidents

Throughout the incident lifecycle, there is frequently the need to communicate with outside parties, including law enforcement, insurance companies, legal counsel, forensic specialists, the media, vendors, external victims, and other IRTs. Having up-to-date contact lists is essential. Because such communications often need to occur quickly, organizations should predetermine communication guidelines and preapprove external resources so that only the appropriate information is shared with the outside parties.

Incident Response Training and Exercises

Establishing a robust response capability ensures that the organization is prepared to respond to an incident swiftly and effectively. Responders should receive training specific to their individual and collective responsibilities. Recurring tests, drills, and challenging incident response exercises can make a huge difference in responder ability. Knowing what is expected decreases the pressure on the responders and reduces errors. It should be stressed that the objective of incident response exercises isn’t to get an “A” but rather to honestly evaluate the plan and procedures, to identify missing resources, and to learn to work together as a team.

What Happened? Investigation and Evidence Handling

The primary reason for gathering evidence is to figure out “what happened” in order to contain and resolve the incident as quickly as possible. As an incident responder, it is easy to get caught up in the moment. It may not be apparent that careful evidence acquisition, handling, and documentation are important or even necessary. Consider the scenario of a workstation malware infection. The first impression may be that the malware download was inadvertent. This could be true or perhaps it was the work of a malicious insider or careless business vendor. Until you have the facts, you just don’t know. Regardless of the source, if the malware infection resulted in a compromise of legally protected information, the company could be a target of a negligence lawsuit or regulatory action, in which case evidence of how the infection was contained and eradicated could be used to support the company’s position. Because there are so many variables, by default, data handlers should treat every investigation as if it would lead to a court case.

Documenting Incidents

The initial documentation should create an incident profile. The profile should include the following:

![]() How was the incident detected?

How was the incident detected?

![]() What is the scenario for the incident?

What is the scenario for the incident?

![]() What time did the incident occur?

What time did the incident occur?

![]() Who or what reported the incident?

Who or what reported the incident?

![]() Who are the contacts for involved personnel?

Who are the contacts for involved personnel?

![]() A brief description of the incident.

A brief description of the incident.

![]() Snapshots of all on-scene conditions.

Snapshots of all on-scene conditions.

All ongoing incident response–related activity should be logged and time stamped. In addition to actions taken, the log should include decisions, record of contact (internal and external resources), and recommendations.

Documentation specific to computer-related activity should be kept separate from general documentation due to the confidential nature of what is being performed and/or found. All documentation should be sequential and time/date stamped, and should include exact commands entered into systems, results of commands, actions taken (for example, logging on, disabling accounts, applying router filters) as well as observations about the system and/or incident. Documentation should occur as the incident is being handled, not after.

Incident documentation should not be shared with anyone outside the team without the express permission of the DIH or executive management. If there is any expectation that the network has been compromised, documentation should not be saved on a network-connected device.

Working with Law Enforcement

Depending on the nature of the situation, it may be necessary to contact local, state, or federal law enforcement. The decision to do so should be discussed with legal counsel. It is important to recognize that the primary mission of law enforcement is to identify the perpetrators and build a case. There may be times when the law enforcement agency requests that the incident or attack continue while they work to gather evidence. Although this objective appears to be at odds with the organizational objective to contain the incident, it is sometimes the best course of action. The IRT should become acquainted with applicable law enforcement representatives before an incident occurs to discuss the types of incidents that should be reported to them, who to contact, what evidence should be collected, and how it should be collected.

If the decision is made to contact law enforcement, it is important to do so as early in the response lifecycle as possible while the trail is still hot. On a federal level, both the Secret Service and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) investigate cyber incidents. The Secret Service’s investigative responsibilities extend to crimes that involve financial institution fraud, computer and telecommunications fraud, identity theft, access device fraud (for example, ATM or point of sale systems), electronic funds transfers, money laundering, corporate espionage, computer system intrusion, and Internet-related child pornography and exploitation. The FBI’s investigation responsibilities include cyber-based terrorism, espionage, computer intrusions, and major cyber fraud. If the missions appear to overlap, it is because they do. Generally, it is best to reach out to the local Secret Service or FBI office and let them determine jurisdiction.

Understanding Forensic Analysis

Forensics is the application of science to the identification, collection, examination, and analysis of data while preserving the integrity of the information. Forensic tools and techniques are often used to find the root cause of an incident or to uncover facts. In addition to reconstructing security incidents, digital forensic techniques can be used for investigating crimes and internal policy violations, troubleshooting operational problems, and recovering from accidental system damage.

As described in NIST Special Publication 800-87, the process for performing digital forensics includes collection, examination, analysis, and reporting:

![]() Collection—The first phase in the process is to identify, label, record, and acquire data from the possible sources of relevant data, while following guidelines and procedures that preserve the integrity of the data. Collection is typically performed in a timely manner because of the likelihood of losing dynamic data such as current network connections, as well as losing data from battery-powered devices.

Collection—The first phase in the process is to identify, label, record, and acquire data from the possible sources of relevant data, while following guidelines and procedures that preserve the integrity of the data. Collection is typically performed in a timely manner because of the likelihood of losing dynamic data such as current network connections, as well as losing data from battery-powered devices.

![]() Examination—Examinations involve forensically processing large amounts of collected data using a combination of automated and manual methods to assess and extract data of particular interest, while preserving the integrity of the data.

Examination—Examinations involve forensically processing large amounts of collected data using a combination of automated and manual methods to assess and extract data of particular interest, while preserving the integrity of the data.

![]() Analysis—The next phase of the process is to analyze the results of the examination, using legally justifiable methods and techniques, to derive useful information that addresses the questions that were the impetus for performing the collection and examination.

Analysis—The next phase of the process is to analyze the results of the examination, using legally justifiable methods and techniques, to derive useful information that addresses the questions that were the impetus for performing the collection and examination.

![]() Reporting—The final phase is reporting the results of the analysis, which may include describing the actions used, explaining how tools and procedures were selected, determining what other actions need to be performed, and providing recommendations for improvement to policies, guidelines, procedures, tools, and other aspects of the forensic process. The formality of the reporting step varies greatly depending on the situation.

Reporting—The final phase is reporting the results of the analysis, which may include describing the actions used, explaining how tools and procedures were selected, determining what other actions need to be performed, and providing recommendations for improvement to policies, guidelines, procedures, tools, and other aspects of the forensic process. The formality of the reporting step varies greatly depending on the situation.

Incident handlers performing forensic tasks need to have a reasonably comprehensive knowledge of forensic principles, guidelines, procedures, tools, and techniques, as well as anti-forensic tools and techniques that could conceal or destroy data. It is also beneficial for incident handlers to have expertise in information security and specific technical subjects, such as the most commonly used operating systems, file systems, applications, and network protocols within the organization. Having this type of knowledge facilitates faster and more effective responses to incidents. Incident handlers also need a general, broad understanding of systems and networks so that they can determine quickly which teams and individuals are well suited to providing technical expertise for particular forensic efforts, such as examining and analyzing data for an uncommon application.

Understanding Chain of Custody

Chain of custody applies to physical, digital, and forensic evidence. Evidentiary chain of custody is used to prove that evidence has not be altered from the time it was collected through production in court. This means that the moment evidence is collected, every transfer of evidence from person to person must be documented and that it must be provable that nobody else could have accessed that evidence. In the case of legal action, the chain of custody documentation will be available to opposing counsel through the information discovery process and may become public. Confidential information should only be included in the document if absolutely necessary.

To maintain an evidentiary chain, a detailed log should be maintained that includes the following information:

![]() Where and when (date and time) evidence was discovered

Where and when (date and time) evidence was discovered

![]() Identifying information such as the location, serial number, model number, hostname, media access control (MAC) address, and/or IP address

Identifying information such as the location, serial number, model number, hostname, media access control (MAC) address, and/or IP address

![]() Name, title, and phone number of each person who discovered, collected, handled, or examined the evidence

Name, title, and phone number of each person who discovered, collected, handled, or examined the evidence

![]() Where evidence was stored/secured and during what time period

Where evidence was stored/secured and during what time period

![]() If the evidence has changed custody, how and when the transfer occurred (include shipping numbers, and so on).

If the evidence has changed custody, how and when the transfer occurred (include shipping numbers, and so on).

The relevant person should sign and date each entry in the record.

Storing and Retaining Evidence

It is not unusual to retain all evidence for months or years after the incident ends. Evidence, logs, and data associated with the incident should be placed in tamper-resistant containers, grouped together, and put in a limited-access location. Only incident investigators, executive management, and legal counsel should have access to the storage facility. If and when evidence is turned over to law enforcement, an itemized inventory of all the items should be created and verified with the law enforcement representative. The law enforcement representative should sign and date the inventory list.

Evidence needs to be retained until all legal actions have been completed. Legal action could be civil, criminal, regulatory, or personnel related. Evidence-retention parameters should be documented in policy. Retention schedules should include the following categories: internal only, civil, criminal, regulatory, personnel-related incident, and to-be-determined (TBD). When categorization is in doubt, legal counsel should be consulted. If there is an organizational retention policy, a notation should be included that evidence-retention schedules (if longer) supersede operational or regulatory retention requirements.

Data Breach Notification Requirements

A component of incident management is to understand, evaluate, and be prepared to comply with the legal responsibility to notify affected parties. Most states have some form of data breach notification laws. Federal regulations, including but not limited to the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA), the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act, the Federal Information Security Management Act (FISMA), and the Federal Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), all address the protection of personally identifiable information (PII; also referred to as non-public personal information, or NPPI) and may potentially apply in an event of an incident.

A data breach is widely defined as an incident that results in compromise, unauthorized disclosure, unauthorized acquisition, unauthorized access, or unauthorized use or loss of control of legally protected PII, including the following:

![]() Any information that can be used to distinguish or trace an individual’s identity, such as name, SSN, date and place of birth, mother’s maiden name, or biometric records.

Any information that can be used to distinguish or trace an individual’s identity, such as name, SSN, date and place of birth, mother’s maiden name, or biometric records.

![]() Any other information that is linked or linkable to an individual, such as medical, educational, financial, and employment information.

Any other information that is linked or linkable to an individual, such as medical, educational, financial, and employment information.

![]() Information that is standing alone is not generally considered personally identifiable, because many people share the same trait, such as first or last name, country, state, ZIP Code, age (without birthdate), gender, race, or job position. However, multiple pieces of information, none of which alone may be considered personally identifiable, may uniquely identify a person when brought together.

Information that is standing alone is not generally considered personally identifiable, because many people share the same trait, such as first or last name, country, state, ZIP Code, age (without birthdate), gender, race, or job position. However, multiple pieces of information, none of which alone may be considered personally identifiable, may uniquely identify a person when brought together.

Incidents resulting in unauthorized access to PII are taken seriously, as the information can be used by criminals to make false identification documents (including drivers’ licenses, passports, and insurance certificates), make fraudulent purchases and insurance claims, obtain loans or establish lines of credit, and apply for government and military benefits.

As we will discuss, the laws vary and sometimes even conflict in their requirements regarding the right of the individual to be notified, the manner in which they must be notified, and the information to be provided. What is consistent, however, is that notification requirements apply regardless of whether an organization stores and manages its data directly or through a third party, such as a cloud service provider.

Is There a Federal Breach Notification Law?

The short answer is, there is not. Consumer information breach notification requirements have historically been determined at the state level. There are, however, federal statutes and regulations that require certain regulated sectors (such as healthcare, financial, and investment) to protect certain types of personal information, implement information security programs, and provide notification of security breaches. In addition, federal departments and agencies are obligated by memorandum to provide breach notification. The Veterans Administration is the only agency with its own law governing information security and privacy breaches.

GLBA Financial Institution Customer Information

Section 501(b) of the GLBA and FIL-27-2005 Guidance on Response Programs for Unauthorized Access to Customer Information and Customer Notice require that a financial institution provide a notice to its customers whenever it becomes aware of an incident of unauthorized access to customer information and, at the conclusion of a reasonable investigation, determines that misuse of the information has occurred or it is reasonably possible that misuse will occur.

Customer notice should be given in a clear and conspicuous manner. The notice should include the following items:

![]() Description of the incident

Description of the incident

![]() Type of information subject to unauthorized access

Type of information subject to unauthorized access

![]() Measures taken by the institution to protect customers from further unauthorized access

Measures taken by the institution to protect customers from further unauthorized access

![]() Telephone number that customers can call for information and assistance

Telephone number that customers can call for information and assistance

![]() A reminder to customers to remain vigilant over the next 12 to 24 months and to report suspected identity theft incidents to the institution

A reminder to customers to remain vigilant over the next 12 to 24 months and to report suspected identity theft incidents to the institution

The guidance encourages financial institutions to notify the nationwide consumer reporting agencies prior to sending notices to a large number of customers that include contact information for the reporting agencies.

Customer notices are required to be delivered in a manner designed to ensure that a customer can reasonably be expected to receive them. For example, the institution may choose to contact all customers affected by telephone, by mail, or by electronic mail (for those customers for whom it has a valid email address and who have agreed to receive communications electronically).

Financial institutions must notify their primary federal regulator as soon as possible when the institution becomes aware of an incident involving unauthorized access to or use of non-public customer information. Consistent with the agencies’ Suspicious Activity Report (SAR) regulations, institutions must file a timely SAR. In situations involving federal criminal violations requiring immediate attention, such as when a reportable violation is ongoing, institutions must promptly notify appropriate law enforcement authorities. Reference Chapter 12, “Business Continuity Management,” for a further discussion of financial institution–related security incidents.

HIPAA/HITECH Personal Healthcare Information (PHI)

The HITECH Act requires that covered entities notify affected individuals when they discover that their unsecured PHI has been, or is reasonably believed to have been, breached—even if the breach occurs through or by a business associate. A breach is defined as “impermissible acquisition, access, or use or disclosure of unsecured PHI... unless the covered entity or business associate demonstrates that there is a low probability that the PHI has been compromised.”

The notification must be made without unreasonable delay and no later than 60 days after the discovery of the breach. The covered entity must also provide notice to “prominent media outlets” if the breach affects more than 500 individuals in a state or jurisdiction. The notice must include the following information:

![]() A description of the breach, including the date of the breach and date of discovery

A description of the breach, including the date of the breach and date of discovery

![]() The type of PHI involved (such as full name, SSN, date of birth, home address, or account number)

The type of PHI involved (such as full name, SSN, date of birth, home address, or account number)

![]() Steps individuals should take to protect themselves from potential harm resulting from the breach

Steps individuals should take to protect themselves from potential harm resulting from the breach

![]() Steps the covered entity is taking to investigate the breach, mitigate losses, and protect against future breaches

Steps the covered entity is taking to investigate the breach, mitigate losses, and protect against future breaches

![]() Contact procedures for individuals to ask questions or receive additional information, including a toll-free telephone number, email address, website, or postal address

Contact procedures for individuals to ask questions or receive additional information, including a toll-free telephone number, email address, website, or postal address

Covered entities must notify the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) of all breaches. Notice to HHS must be provided immediately for breaches involving more than 500 individuals and annually for all other breaches. Covered entities have the burden of demonstrating that they satisfied the specific notice obligations following a breach, or, if notice is not made following an unauthorized use or disclosure, that the unauthorized use or disclosure did not constitute a breach. Reference Chapter 13, “Regulatory Compliance for Financial Institutions,” for a further discussion of healthcare-related security incidents.

Section 13407 of the HITECH Act directed the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to issue breach notification rules pertaining to the exposure or compromise of personal health records (PHRs). A personal health record is defined by the FTC as an electronic record of “identifiable health information on an individual that can be drawn from multiple sources and that is managed, shared, and controlled by or primarily for the individual.” Don’t confuse PHR with PHI. PHI is information that is maintained by a covered entity as defined by HIPAA/HITECH. PHR is information provided by the consumer for the consumer’s own benefit. For example, if a consumer uploads and stores medical information from many sources in one online location, the aggregated data would be considered a PHR. The online service would be considered a PHR vendor.

The FTC rule applies to both vendors of PHRs (which provide online repositories that people can use to keep track of their health information) and entities that offer third-party applications for PHRs. The requirements regarding the scope, timing, and content mirror the requirements imposed on covered entities. The enforcement is the responsibility of the FTC. By law, noncompliance is considered “unfair and deceptive trade practices.”

Federal Agencies

Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Memorandum M-07-16: Safeguarding Against and Responding to the Breach of Personally Identifiable Information requires all federal agencies to implement a breach notification policy to safeguard paper and digital PII. Attachment 3, “External Breach Notification,” identifies the factors agencies should consider in determining when notification outside the agency should be given and the nature of the notification. Notification may not be necessary for encrypted information. Each agency is directed to establish an agency response team. Agencies must assess the likely risk of harm caused by the breach and the level of risk. Agencies should provide notification without unreasonable delay following the detection of a breach, but are permitted to delay notification for law enforcement, national security purposes, or agency needs. Attachment 3 also includes specifics as to the content of the notice, criteria for determining the method of notification, and the types of notice that may be used. Attachment 4, “Rules and Consequences Policy,” states that supervisors may be subject to disciplinary action for failure to take appropriate action upon discovering the breach or failure to take the required steps to prevent a breach from occurring. Consequences may include reprimand, suspension, removal, or other actions in accordance with applicable law and agency policy.

Veterans Administration

On May 3, 2006, a data analyst at Veterans Affairs took home a laptop and an external hard drive containing unencrypted information on 26.5 million people. The computer equipment was stolen in a burglary of the analyst’s home in Montgomery County, Maryland. The burglary was immediately reported to both Maryland police and his supervisors at Veterans Affairs. The theft raised fears of potential mass identity theft. On June 29, the stolen laptop computer and hard drive were turned in by an unidentified person. The incident resulted in Congress imposing specific response, reporting, and breach notification requirements on the Veterans Administration (VA).

Title IX of P.L. 109-461, the Veterans Affairs Information Security Act, requires the VA to implement agency-wide information security procedures to protect the VA’s “sensitive personal information” (SPI) and VA information systems. P.L. 109-461 also requires that in the event of a “data breach” of SPI processed or maintained by the VA, the Secretary must ensure that as soon as possible after discovery, either a non-VA entity or the VA’s Inspector General conduct an independent risk analysis of the data breach to determine the level of risk associated with the data breach for the potential misuse of any SPI. Based on the risk analysis, if the Secretary determines that a reasonable risk exists of the potential misuse of SPI, the Secretary must provide credit protection services.

P.L. 109-461 also requires the VA to include data security requirements in all contracts with private-sector service providers that require access to SPI. All contracts involving access to SPI must include a prohibition of the disclosure of such information, unless the disclosure is lawful and expressly authorized under the contract, as well as the condition that the contractor or subcontractor notify the Secretary of any data breach of such information. In addition, each contract must provide for liquidated damages to be paid by the contractor to the Secretary in the event of a data breach with respect to any SPI, and that money should be made available exclusively for the purpose of providing credit protection services.

State Breach Notification Laws

In the absence of federal consumer breach notification law, 46 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands have enacted notification laws designed to protect their residents. The intent of state breach notification laws is to require companies that collect data belonging to residents of their state to notify residents of their state if there is a data breach of said information. States with no security breach law include Alabama, Kentucky, New Mexico, and South Dakota. California, Massachusetts, and Texas laws are notable:

![]() California was the first to adopt a security breach notification law. The California Security Breach Information Act (California Civil Code Section 1798.82), effective July 1, 2003, required companies based in California or with customers in California to notify them whenever their personal information may have been compromised. This groundbreaking legislation provided the model for states around the country.

California was the first to adopt a security breach notification law. The California Security Breach Information Act (California Civil Code Section 1798.82), effective July 1, 2003, required companies based in California or with customers in California to notify them whenever their personal information may have been compromised. This groundbreaking legislation provided the model for states around the country.

![]() MA Chapter 93H Massachusetts Security Breach Notification Law, enacted in 2007, and the subsequent 201 CMR 17 Standards for the Protection of Personal Information of Residents of the Commonwealth, is widely regarded as the most comprehensive state information security legislation.

MA Chapter 93H Massachusetts Security Breach Notification Law, enacted in 2007, and the subsequent 201 CMR 17 Standards for the Protection of Personal Information of Residents of the Commonwealth, is widely regarded as the most comprehensive state information security legislation.

![]() The Texas Breach Notification Law was amended in 2011 to require entities doing business within the state to provide notification of data breaches to residents of states that have not enacted their own breach notification law. In 2013, this provision was removed. Additionally, in 2013, an amendment was added that notice provided to consumers in states that require notification can comply with either the Texas law or the law of the state in which the individual resides.

The Texas Breach Notification Law was amended in 2011 to require entities doing business within the state to provide notification of data breaches to residents of states that have not enacted their own breach notification law. In 2013, this provision was removed. Additionally, in 2013, an amendment was added that notice provided to consumers in states that require notification can comply with either the Texas law or the law of the state in which the individual resides.

The basic premise of the state security breach laws is that consumers have a right to know if unencrypted personal information such as SSN, driver’s license number, state identification card number, credit or debit card number, account password, PINs, or access codes have either been or are suspected to be compromised. The concern is that the listed information could be used fraudulently to assume or attempt to assume a person’s identity. Exempt from legislation is publicly available information that is lawfully made available to the general public from federal, state, or local government records or by widely distributed media.

State security breach notification laws generally follow the same framework, which includes who must comply, a definition of personal information and breach, the elements of harm that must occur, triggers for notification, exceptions, and the relationship to federal law and penalties and enforcement authorities. Although the framework is standard, the laws are anything but. The divergence begins with the differences in how personal information is defined and who is covered by the law, and ends in aggregate penalties that range from $50,000 to $500,000. The variations are so numerous that compliance is confusing and onerous.

It is strongly recommended that any organization that experiences a breach or suspected breach of PII consult with legal counsel for interpretation and application of the myriad of sector-based, federal, and state incident response and notification laws.

Does Notification Work?

In the previous section, we discussed sector-based, federal, and state breach notification requirements. Notification can be resource intensive, time consuming, and expensive. The question that needs to be asked is, is it worth it? The resounding answer from privacy and security advocates, public relations (PR) specialists, and consumers is “yes.” Consumers trust those who collect their personal information to protect it. When that doesn’t happen, they need to know so that they can take steps to protect themselves from identity theft, fraud, and privacy violations.

In June 2012, Experian commissioned the Ponemon Institute to conduct a consumer study on data breach notification. The findings are instructive. When asked “What personal data if lost or stolen would you worry most about?”, they overwhelmingly responded “password/PIN” and “Social Security number.”

![]() Eighty-five percent believe notification about data breach and the loss or theft of their personal information is relevant to them.

Eighty-five percent believe notification about data breach and the loss or theft of their personal information is relevant to them.

![]() Fifty-nine percent believe a data breach notification means there is a high probability they will become an identity theft victim.

Fifty-nine percent believe a data breach notification means there is a high probability they will become an identity theft victim.

![]() Fifty-eight percent say the organization has an obligation to provide identity protection services, and 55% say they should provide credit-monitoring services.

Fifty-eight percent say the organization has an obligation to provide identity protection services, and 55% say they should provide credit-monitoring services.

![]() Seventy-two percent were disappointed in the way the notification was handled. A key reason for the disappointment is respondents’ belief that the notification did not increase their understanding about the data breach.

Seventy-two percent were disappointed in the way the notification was handled. A key reason for the disappointment is respondents’ belief that the notification did not increase their understanding about the data breach.

The Public Face of a Breach

It’s tempting to keep a data breach secret, but not reasonable. Consumers need to know when their information is at risk so they can respond accordingly. Once notification has gone out, rest assured that the media will pick up the story. Breaches attract more attention than other technology-related topic, so reporters are more apt to cover them to drive traffic to their sites. If news organizations learn about these attacks through third-party sources while the breached organization remains silent, the fallout can be significant. Organizations must be proactive in their PR approach, using public messaging to counteract inaccuracies and tell the story from their point of view. Doing this right can save an organization’s reputation and even, in some cases, enhance the perception of its brand in the eyes of customers and the general public. The PR professionals advise following these straightforward but strict rules when addressing the media and the public:

![]() Get it over with.

Get it over with.

![]() Be humble.

Be humble.

![]() Don’t lie.

Don’t lie.

![]() Say only what needs to be said.

Say only what needs to be said.

Don’t wait until a breach happens to develop a RP preparedness plan—communications should be part of any incident preparedness strategy. Security specialists should work with PR people to identify the worst possible breach scenario so they can message against it and determine audience targets, including customers, partners, employees, and the media. Following a breach, messaging should be bulletproof and consistent.

Summary

An information security incident is an adverse event that threatens business security and/or disrupts operations. Examples include intentional unauthorized access, DDoS attacks, malware, and inappropriate usage. The objective of an information security risk management program is to minimize the number of successful attempts and attacks. The reality is that security incidents happen even at the most security-conscious organizations. Every organization should be prepared to respond to an incident quickly, confidently, and in compliance with applicable laws and regulations.

The objective of incident management is a consistent and effective approach to the identification of and response to information security–related incidents. Meeting that objective requires situational awareness, incident reporting mechanisms, a documented IRP, and an understanding of legal obligations. Incident preparation includes developing strategies and instructions for documentation and evidence handling, detection and investigation (including forensic analysis), containment, eradication and recovery, notification, and closure. The roles and responsibilities of key personnel, including executive management, legal counsel, incident response coordinators (IRCs), designated incident handlers (DIHs), the incident response team (IRT), and ancillary personnel as well as external entities such as law enforcement and regulatory agencies, should be clearly defined and communicated. Incident response capabilities should be practiced and evaluated on an ongoing basis.

Consumers have a right to know if their personal data has been compromised. In most situations, data breaches of PII must be reported to the appropriate authority and affected parties notified. A data breach is generally defined as actual or suspected compromise, unauthorized disclosure, unauthorized acquisition, unauthorized access, or unauthorized use or loss of control of legally protected PII. Forty-six states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands have enacted consumer notification laws designed to protect their residents. In addition to state laws, there are sector- and agency-specific federal regulations that pertain to reporting and notification. Organizations that experience a breach or suspected breach of PII should consult with legal counsel for interpretation and application of often overlapping and contradictory rules and expectations.

Incident management policies include Incident Definition Policy, Incident Classification Policy, Information Response Program Policy, Incident Response Authority Policy, Evidence Handling and Use Policy, and Data Breach Reporting and Notification Policy.

Test Your Skills

Multiple Choice Questions

1. Which of the following statements best defines incident management?

A. Incident management is risk minimization.

B. Incident management is a consistent approach to responding to and resolving issues.

C. Incident management is problem resolution.

D. Incident management is forensic containment.

2. Which of the following statements is true of security-related incidents?

A. Over time, security-related incidents have become less prevalent and less damaging.

B. Over time, security-related incidents have become more prevalent and more disruptive.

C. Over time, security-related incidents have become less prevalent and more damaging.

D. Over time, security-related incidents have become more numerous and less disruptive.

3. Minimizing the number of incidents is a function of which of the following?

A. Incident response testing

B. Forensic analysis

C. Risk management

D. Security investments

4. An information security incident can ___________.

A. compromise business security

B. disrupt operations

C. impact customer trust

D. All of the above

5. Which of the following statements is true when an information security–related incident occurs at a business partner or vendor who hosts or processes legally protected data on behalf of an organization?

A. The organization does not need to do anything.

B. The organization must be notified and respond accordingly.

C. The organization is not responsible.

D. The organization must report the incident to local law enforcement.

6. Which of the following attack types best describes a targeted attack that successfully obstructs functionality?

A. Spam attack

B. Malware attack

C. DDoS attack

D. Killer attack

7. A celebrity is admitted to the hospital. If an employee accesses the celebrity’s patient record just out of curiosity, the action is referred to as __________.

A. inappropriate usage

B. unauthorized access

C. unacceptable behavior

D. undue care

8. Employees who report incidents should be ___________.

A. prepared to assign a severity level

B. praised for their actions

C. provided compensation

D. None of the above

9. Which of the following statements is true of an incident response plan?

A. An incident response plan should be updated and authorized annually.

B. An incident response plan should be documented.

C. An incident response plan should be stress tested.

D. All of the above

10. Which of the following terms best describes a signal or warning that an incident may occur in the future?

A. A sign

B. A precursor

C. An indicator

D. Forensic evidence

11. Which of the following terms best describes the process of taking steps to prevent the incident from spreading?

A. Detection

B. Containment

C. Eradication

D. Recovery

12. Which of the following terms best describes the addressing of the vulnerabilities related to the exploit or compromise and restoring normal operations?

A. Detection

B. Containment

C. Testing

D. Recovery

13. Which of the following terms best describes the eliminating of the components of the incident?

A. Investigation

B. Containment

C. Eradication

D. Recovery

14. Which of the following terms best describes the substantive or corroborating evidence that an incident may have occurred or may be occurring now?

A. Indicator of compromise

B. Forensic proof

C. Heresy

D. Diligence

15. Which of the following is not generally an incident response team responsibility?

A. Incident impact analysis

B. Incident communications

C. Incident plan auditing

D. Incident management

16. Incident response activity logs should not include which of the following?

A. Date

B. Time

C. Decisions made

D. Cost of the activity

17. The decision to contact law enforcement should be made ______________.

A. early in the incident lifecycle

B. once an incident has been verified

C. after evidence has been collected

D. only if there is a loss of funds

18. Which of the following agencies’ investigative responsibilities include financial fraud, money laundering, and identity theft?

A. FBI

B. Department of Homeland Security

C. Secret Service

D. State Police

19. Documentation of the transfer of evidence is known as a ____________.

A. chain of evidence

B. chain of custody

C. chain of command

D. chain of investigation

20. Data breach notification laws pertain to which of the following?

A. Intellectual property

B. Patents

C. PII

D. Products

21. Federal breach notification laws apply to _____________.

A. specific sectors such as financial and healthcare

B. all United States citizens

C. any disclosure of a Social Security number

D. None of the above

22. HIPAA/HITECH requires ______________ within 60 days of the discovery of a breach.

A. notification be sent to affected parties

B. notification be sent to law enforcement

C. notification be sent to Department of Health and Human Services

D. notification be sent to all employees

23. With the exception of the ___________, all federal agencies are required to act in accordance with OMB M-07-16: “Safeguarding Against and Responding to the Breach of Personally Identifiable Information” guidance.

A. Department of Health and Human Services

B. Federal Reserve

C. Internal Revenue Service

D. Veterans Administration

24. Which of the following statements is true of state breach notification laws?

A. Notification requirements are the same in every state.

B. State laws exist because there is no comparable federal law.

C. Every state has a state breach notification law.

D. The laws only apply to verified breaches.

25. Which of the following states was the first state to enact a security breach notification law?

A. Massachusetts

B. Puerto Rico

C. California

D. Alabama

26. Which of the following statements is true concerning the Texas security breach notification law?

A. The Texas security breach notification law includes requirements that in-state businesses provide notice to residents of all states.

B. The Texas security breach notification law includes requirements that in-state businesses only provide notice to residents of Texas.

C. The Texas security breach notification law includes requirements that in-state businesses are exempt from notification requirements.

D. The Texas security breach notification law includes requirements that in-state businesses provide notice internationally.

27. Consumers are most concerned about compromise of their _______________.

A. password/PIN and SSN

B. email address

C. checking account number

D. address and date of birth

28. Which of the following statements is true?

A. Consumers want to be notified of a data breach and they overwhelmingly expect to be compensated.

B. Consumers want to be notified of a data breach and they overwhelmingly expect to be provided as much detail as possible.

C. Consumers want to be notified of a data breach and they overwhelmingly expect to be told when the criminal is apprehended.

D. Consumers want to be notified of a data breach and they overwhelmingly expect to be interviewed by investigators.

29. Incident response plans and procedures should be tested ____________.

A. during development

B. upon publication

C. on an ongoing basis

D. only when there are changes

30. The Board of Directors (or equivalent body) is responsible for ____________.

A. the cost of notification

B. contacting regulators

C. managing response efforts

D. authorizing incident response policies

Exercises

Exercise 11.1: Assessing an Incident Report

1. At your school or workplace, locate information security incident reporting guidelines.

2. Evaluate the process. Is it easy to report an incident? Are you encouraged to do so?

3. How would you improve the process?

Exercise 11.2: Evaluating an Incident Response Policy

1. Locate an incident response policy document either at your school, workplace, or online. Does the policy clearly define the criteria for an incident?

2. Does the policy define roles and responsibilities? If so, describe the response structure (for example, who is in charge, who should investigate an incident, who can talk to the media). If not, what information is the policy missing?

3. Does the policy include notification requirements? If yes, what laws are referenced and why? If no, what laws should be referenced?

Exercise 11.3: Researching Containment and Eradication

1. Research and identify the latest strains of malware.

2. Choose one. Find instructions for containment and eradication.

3. Conventional risk management wisdom is that it is better to replace a hard drive than to try to remove malware. Do you agree? Why or why not?

Exercise 11.4: Researching a DDoS Attack

1. Find a recent news article about DDoS attacks.

2. Who were the attackers and what was their motivation?

3. What was the impact of the attack? What should the victim organization do to mitigate future damage?

Exercise 11.5: Understanding Evidence Handling

1. Create a worksheet that could be used by an investigator to build an “incident profile.”

2. Create an evidentiary “chain of custody” form that could be used in legal proceedings.

3. Create a log for documenting forensic or computer-based investigation.

Projects

Project 11.1: Creating Incident Awareness

1. One of the key messages to be delivered in training and awareness programs is the importance of incident reporting. Educating users to recognize and report suspicious behavior is a powerful deterrent to would-be intruders. The organization you work for has classified the following events as high priority, requiring immediate reporting:

![]() Customer data at risk of exposure or compromise

Customer data at risk of exposure or compromise

![]() Unauthorized use of a system for any purpose

Unauthorized use of a system for any purpose

![]() Unauthorized downloads of software, music, or videos

Unauthorized downloads of software, music, or videos

![]() Missing equipment

Missing equipment

![]() Suspicious person in the facility

Suspicious person in the facility

You have been tasked with training all users to recognize these types of incidents.

1. Write a brief explanation of why each of the listed events is considered high priority. Include at least one example per event.

2. Create a presentation that can be used to train employees to recognize these incidents and how to report them.

3. Create a ten-question quiz that tests their post-presentation knowledge.

Project 11.2: Assessing Security Breach Notifications

Access the State of New Hampshire, Department of Justice, Office of the Attorney General security breach notification web page. Sort the notifications by year.

1. Read three recent notification letters to the Attorney General as well as the corresponding notice that will be sent to the consumer (be sure to scroll through the document). Write a summary and timeline (as presented) of each event.

2. Choose one incident to research. Find corresponding news articles, press releases, and so on.

3. Compare the customer notification summary and timeline to your research. In your opinion, was the notification adequate? Did it include all pertinent details? What controls should the company put in place to prevent this from a happening again?

Project 11.3: Comparing and Contrasting Regulatory Requirements

The objective of this project is to compare and contrast breach notification requirements.

1. Create a grid that includes state, statute, definition of personal information, definition of a breach, timeframe to report a breach, reporting agency, notification requirements, exemptions, and penalties for nonconformance. Fill in the grid using information from five states.

2. If a company who did business in all five states experienced a data breach, would it be able to use the same notification letter for consumers in all five states? Why or why not?

3. Create a single notification law using what you feel are the best elements of the five laws included in the grid. Be prepared to defend your choices.

References

Regulations Cited

“16 C.F.R. Part 318: Health Breach Notification Rule: Final Rule—Issued Pursuant to the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009—Requiring Vendors of Personal Health Records and Related Entities To Notify Consumers When the Security of Their Individually Identifiable Health Information Has Been Breached,” Federal Trade Commission, accessed 10/2013, www2.ftc.gov/opa/2009/08/hbn.shtm.

“Appendix B to Part 364—Interagency Guidelines Establishing Information Security Standards,” accessed 08/2013, www.fdic.gov/regulations/laws/rules/2000-8660.html.

“201 CMR 17.00: Standards for the Protection of Personal Information of Residents of the Commonwealth,” official website of the Office of Consumer Affairs & Business Regulation (OCABR), accessed 05/06/2013, www.mass.gov/ocabr/docs/idtheft/201cmr1700reg.pdf.

“Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA),” official website of the U.S. Department of Education, accessed 05/2013, www.ed.gov/policy/gen/guid/fpco/ferpa/index.html.

“Financial Institution Letter (FIL-27-2005), Final Guidance on Response Programs for Unauthorized Access to Customer Information and Customer Notice,” accessed 10/2013, www.fdic.gov/news/news/financial/2005/fil2705.html.

“HIPAA Security Rule,” official website of the Department of Health and Human Services, accessed 05/2013, http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/administrative/securityrule/.

“Modifications to the HIPAA Privacy, Security, Enforcement, and Breach Notification Rules 45 CFR Parts 160 and 164 Under the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act; Other Modifications to the HIPAA Rules; Final Rule,” Federal Register, Volume 78, No. 17, January 25, 2013, accessed 06/2013, www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/administrative/omnibus/.

“Office of Management and Budget Memorandum M-07-16 Safeguarding Against and Responding to the Breach of Personally Identifiable Information,” accessed 10/2013, www.whitehouse.gov/OMB/memoranda/fy2007/m07-16.pdf.

State of California, “SB 1386: California Security Breach Information Act, Civil Code Section 1798.80-1798.84,” Official California Legislative Information, accessed 05/2013, www.leginfo.ca.gov/cgi-bin/displaycode?section=civ&group=01001-02000&file=1798.80-1798.84.

State of Texas, Business and Commerce Code, Sections 521.053, accessed 10/2013, ftp://ftp.legis.state.tx.us/bills/83R/billtext/html/senate_bills/SB01600_SB01699/SB01610H.htm.

Other References

“2012 Consumer Study on Data Breach Notification,” Ponemon Institute, LLC, June 2012, accessed 10/2013, www.experian.com/assets/data-breach/brochures/ponemon-notification-study-2012.pdf.

“Chain of Custody and Evidentiary Issues,” eLaw Exchange, accessed 10/2013, www.elawexchange.com.

“Complying with the FTC’s Health Breach Notification Rule,” April 2010, FTC Bureau of Consumer Protection, accessed 10/2013, www.business.ftc.gov/documents/bus56-complying-ftcs-health-breach-notification-rule.

“Consumer Study on Data Breach Notification” Ponemon Institute, LLC, 2012, accessed 10/2013, www.experian.com/data-breach/ponemon-notification-study.html.

“Data Breach Response Checklist PTAC-CL, September 2012,” Department of Education, Privacy Technical Assistance Center, accessed 10/2013, http://ptac.ed.gov/document/checklist-data-breach-response-sept-2012.

“Electronic Crime Scene Investigation: A Guide for First Responders, Second Edition,” U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice, April 2008, accessed 10/2013, www.nij.gov/nij/pubs-sum/219941.htm.

“Forensic Examination of Digital Evidence: A Guide for Law Enforcement,” U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice, April 2004, accessed 10/2013, www.nij.gov/pubs-sum/199408.htm.

“FTC Issues Final Breach Notification Rule for Electronic Health Information,” Federal Trade Commission, accessed 10/2013, www2.ftc.gov/opa/2009/08/hbn.shtm.

“Incident Response Procedures for Data Breaches, 0900.00.01,” U.S. Department of Justice, August 6, 2013, accessed October 2013, www.justice.gov/opcl/breach-procedures.pdf.

“Information Technology Security Incident Response Plan v1.0,” February 15, 2010, University of Connecticut, accessed 10/2013, http://security.uconn.edu/wp-content/blogs.dir/14/files/2010/07/security-incident-response-procedures.pdf.

“IT Security Incident Response HIPAA Policy 01/02/2012,” Yale University, accessed 10/2013, www.yale.edu/ppdev/policy/5143/5143.pdf.

“Largest Incidents,” DataLossdb Open Security Foundation, accessed 10/2013, www.datalossdb.org.

Lee, Christopher and Zachary A. Goldfarb. “Stolen VA Laptop and Hard Drive Recovered,” Washington Post, Friday, June 30, 2006, accessed 2013, www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/06/29/AR2006062900352.html.

Mandia, Kevin and Chris Prosise. Incident Response: Investigating Computer Crime, Berkeley, California: Osborne/McGraw-Hill, 2001.

Nolan, Richard, “First Responders Guide to Computer Forensics,” 2005, Carnegie Mellon University Software Engineering Institute.

“Pennsylvania Man Pleads Guilty to Hacking into Multiple Computer Networks,” U.S. Attorney’s Office, August 27, 2013, District of Massachusetts, Federal Bureau of Investigation, accessed 10/2013, www.fbi.gov/boston/press-releases/2013/pennsylvania-man-pleads-guilty-to-hacking-into-multiple-computer-networks.

Proffit, Tim, “Creating and Maintaining Policies for Working with Law Enforcement,” 2008, SANS Institute.

“Responding to IT Security Incidents,” Microsoft Security TechCenter, accessed 10/2013, http://technet.microsoft.com/en-us/library/cc700825.aspx.

“Searching and Seizing Computers and Obtaining Electronic Evidence in Criminal Investigations,” United States Department of Justice, accessed 10/2013, www.cybercrime.gov/s&smanual2002.htm.

“Security Breach Notification Legislation/Laws,” National Conference of State Legislatures, accessed 10/2013, www.ncsl.org/research/telecommunications-and-information-technology/overview-security-breaches.aspx.

Stevens, Gina, “Data Security Breach Notification Laws,” April 20, 2012, Congressional Research Service, accessed 10/2013, www.crs.gov.

“Texas amends data breach notification law to remove out-of-state obligations,” Winston and Strawn, LLP, accessed 10/2013, www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=eda7fb1a-a4a4-4041-8966-e65137c9d5e9.

“The Massachusetts Data Security Law and Regulations,” McDermott, Will & Emery, November 2, 2009, accessed 10/2013, www.mwe.com.

“United States Computer Emergency Readiness Team,” US-CERT, accessed 10/2013, www.us-cert.gov/.

“2013 Data Breach Investigations Report, Verizon,” Verizon, accessed 10/2013, www.verizonenterprise.com/DBIR/2013.