CHAPTER 2: DEFINE SELECTION PARAMETERS

Once you’ve identified a need to select a new system or service, the temptation is to simply ‘get on with it’ and immediately start to look at possible options. However, there are a number of important steps to take before you do that. These are:

- Decide who should be involved in the selection process.

- Make sure you have clear reasons for doing the selection.

- Make sure you know what outcome you expect from the selection (i.e. what you expect to achieve from having the new system or service).

- Agree the scope of the selection (i.e. where the boundaries are, what’s included and, importantly, what’s excluded).

- Have a good idea of the business case (i.e. likely cost versus expected benefits).

- Understand any constraints the selection will need to meet.

In this chapter we will go through these steps in detail. You will also need to gather, and agree, all the requirements for the new system or service; this task is covered in Chapter 4.

Who should be involved?

This depends very much on what’s being selected and also on your organisation. The number of people to be involved can be quite a balancing act.

Too few and it is hard to demonstrate fairness in the choice (plus there is great value in having enough people to review documents, check for assumptions, and so on). Too many and the team becomes unwieldy; matching diaries for meetings can be almost impossible, causing lengthy delays.

The optimal number for a selection team is around four to six people. This gives you enough people to give a fair assessment of options, without having so many that the whole process becomes cumbersome. Bear in mind that you will have to arrange meetings with the whole selection team and this could include pitch meetings, visits to reference sites, and so on, which can be very time-consuming.

But you may need a smaller or larger team. For example, a small organisation doing a straightforward selection could have a team of two or three people. Whereas a medium size organisation selecting a business critical system may need a selection team on the large side, perhaps up to eight people.

So, how do you decide? There are a number of elements to consider:

- Key stakeholders: Who will be using the system/service? Who will be managing it? Who will be affected by it? Are there different stakeholder groups that need to be represented?

- Level of change to the business: If the new system or service is going to cause a major change to a business process or to the way your business operates (i.e. its culture), you should normally involve more people in the selection, in order to increase the buy-in to the final solution.

- Business criticality: How critical will the new system or service be to your business? For example, a finance system is likely to be fairly critical, whereas a new supplier for stationery may be less so.

- Likely costs: For a system – how much is it likely to cost to buy, how much to implement it and roll it out, and how much to support it annually? For a service – what are the likely fees and is it for a one-off service or an ongoing one? If the latter, how long do you expect the initial contract to be? The higher the cost, the greater the level of governance – and likely, the number of people involved in the selection.

If these considerations mean that you really want to involve a lot more people, then one possible way to manage this is to have a core team that do the main selection activities, with each of these directly representing a number of other stakeholders. Each core team member will need to get input from, and report back to, those people they are representing. (Also, it’s possible to involve a much wider group in the requirements gathering – see Chapter 4.)

The above considerations will also affect the formality of the documentation produced during the selection process. If there are many people interested in the selection, it’s useful to document the proceedings more formally, so that everyone can read the reports and have a chance to feed back any comments.

You may also need to advise other stakeholders that the selection is going on, and keep them informed through the process. One example is your legal advisor (if you have one), as they will become involved once you get to the contract stage, and this is much easier if they’ve been kept informed of overall progress as you go.

Why are you doing it?

There are two main categories of reasons for undertaking a selection:

- ‘Push’ reasons: this is when you have to make a selection for some reason. For example, to replace an ageing system or an unreliable supplier, or to meet new legislative requirements.

- ‘Pull’ reasons: these are when you want to make a selection in order to meet your business objectives. For example, a new system to enable you to get a competitive advantage, or when using a new supplier could save you money.

It’s quite possible for a selection to have reasons from both categories. For instance, an organisation that has been using spreadsheets to perform a business function may want to move to a full IT system because growth in the business means that more functionality is needed (a ‘push’ reason), plus a new system would enable them to process orders more efficiently (a ‘pull’ reason).

Indeed, if you are undertaking a selection for a ‘push’ reason, it’s well worth thinking about any other ‘pull’ benefits you could get from it. After all, if you’ve got to go through the exercise anyway, why not get some additional business advantage from it?

Whatever your reasons, it’s important that these are clearly stated and agreed by the selection team. If this is not done, team members will approach the selection tasks from differing perspectives, which could result in discord and misunderstandings.

These agreed reasons will feed into the outcomes and business case considerations which follow.

What are the outcomes?

Following on from agreeing the reasons for the selection, it’s also worth considering what you expect the outcomes to be. This isn’t just the obvious one of having a new system or supplier!

Rather, you should be thinking about what having the new system or supplier will actually achieve. Are you looking to make your business more competitive in the market? If so, how will this new system help? Or maybe you’re expecting cost savings or other efficiencies? What will this give you?

At this point, the outcomes are likely to still be fairly high level. They will be further broken down into specific benefits as part of the business case.

Typical examples for an order processing system are:

- Improved efficiency in order fulfilment when using the new system will improve customer satisfaction and increase the level of re-orders.

- Use of just-in-time ordering with the new service will reduce stock levels enabling savings on warehouse space and extending the life of the current building.

What is the scope?

Another important element to clarify at this stage is the scope of the new system or service. Where are the boundaries? What’s included and, also important, what’s excluded?

There can be a number of elements to this, including:

- Which parts of the organisation will be affected? (E.g. will the new system be used by a specific team only, such as a human resources system, or will everyone be using it, such as a new e-mail system?)

Note: After this has been agreed, it’s worth reviewing the selection team. Have you included representatives from all relevant areas? - What business functions, activities and processes will be affected? It’s especially important to agree the scope if business processes will need to change. (E.g. does a system only need to deal with active records or does it need to include an archiving facility?)

- What existing systems or services will be replaced? This is especially true for IT systems because of the need to consider data migration.

Is the business case realistic?

Whether or not you need to undertake a formal business case will depend on your own organisation’s governance processes. If you will need to produce one, it’s useful to start thinking about it early on, but even if you don’t have to, you should still be checking to make sure that the planned new system or service will be cost justified.

A business case at its simplest is a comparison between costs and expected benefits. If the benefits outweigh the costs, then the business case is likely to be justified.

So, you should first consider the likely costs. At this point, you will probably only have a rough idea of these, but it’s still worth recording them; you can refine them as the selection progresses. Possible costs for a new system can include:

- the purchase cost (this can be licences, software modules or a combination)

- any new hardware needed (this could be direct, like a server, or indirect, like needing additional bandwidth for your Internet connection, so that remote users can access the system)

- any other software that will be needed

- if you’re looking for a hosted option, then there will be an annual user cost

- implementation and rollout costs

- training costs (for end users, as well as those who will support the system internally)

- user support related costs (e.g. developing a user manual or a user help system)

- annual support and maintenance costs.

Possible costs for a new service are likely to be more straightforward, but you should consider any exceptional or additional costs that may be charged (e.g. for urgent orders, out-of-hours work, multiple locations, etc.).

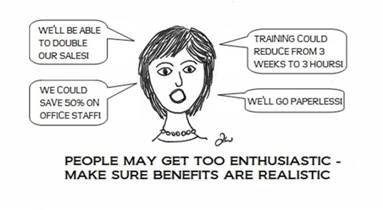

Next, you should draft your expected benefits. Again, these will probably be refined as the selection progresses, but you should be able to produce a reasonable list now. Based on your reasons and outcomes, draw up a more detailed list of the specific benefits that you expect to gain. For each benefit, you should aim to capture:

- A detailed description of the benefit. What exactly is it? If a benefit is too high level (e.g. increase productivity), it’s very hard to focus on making sure it will happen and is also hard to measure.

- Information on who will gain from it (teams/people). It’s useful if a key person can ‘own’ the benefit; they will then have responsibility for making sure the selection will enable the benefit to be achieved.

- Details on how you will measure success. As well as a measurement, you will probably need a baseline figure as a comparison. For example, there’s no point in saying ‘increase sales of widgets by 10%’ if you don’t provide a baseline figure. It’s worth trying to put a financial figure on each benefit to enable a comparison with the costs. This can be difficult, but you can usually find some means of doing this (e.g. ‘improving staff morale’ seems fairly intangible, but will have some hard financial impact by reducing staff turnover and levels of sickness).

- When you expect to see the benefit. Some may be seen immediately after implementation (e.g. you are able to produce invoices electronically as soon as the new system is rolled out), whereas others may take some months (e.g. an improvement in sales or reduction in costs may take some months to be seen).

An example of a badly drafted benefit is:

To improve productivity within the claims team to enable cost savings.

A better attempt could be:

To improve the productivity of the claims handlers within the claims team, by making the online claims form process faster, more efficient and streamlined, to reduce the average time taken to process a form from 30 to 15 minutes. This improvement is expected to enable the team of 10 to be reduced to nine after three months in operation, to be achieved by not renewing a temporary contract, saving £15,000pa.

If you produce detailed benefits now it makes it much easier to check that the business case is viable and also to review the benefits later on. It’s a good discipline to review benefit achievement at a realistic date (often three or six months) after the new system goes live or the new service starts to be used (indeed this may already be part of your project management process).

Once you’ve done this, you can compare the costs against the benefits, and make sure that the business case can be justified.

Are there any constraints?

You need to understand fully any constraints the selection will need to meet. This could include:

- being within a certain budget

- meeting a deadline (e.g. if an existing service contract expires on a certain date, the new one must be ready to replace it)

- complying with any legal requirements (e.g. levels of accessibility, data protection)

- conforming to your technical environment (unless you’re willing to make other technical changes to enable it – and these could be extensive, and expensive)

- conforming to any ethical stance your organisation may have (e.g. your environmental policy).

These constraints will feed into the requirements gathering in the next chapter and will prove useful in filtering out less appropriate options.

Case study: Make sure there’s no hidden dissent!

A large charity needed to replace their ageing fleet of printers and photocopiers. They went through the selection process and assessed a number of potential suppliers who could provide and manage the machines. The process seemed to run smoothly and eventually a preferred supplier was agreed upon by the selection team.

However, during a pre-contract pilot stage, it became apparent that the IT team were not satisfied with this type of managed service. This concern had not come out during the selection process; indeed it had been agreed that a managed service was a viable choice. After the pilot, it was decided not to go ahead with the contract; instead, the IT team purchased the machines directly and installed them using in-house staff.

Although the outcome was eventually satisfactory, this fundamental change in requirement meant that the selection process was effectively a waste of time and resources, not only for the charity, but also for the suppliers involved. It was especially frustrating for the preferred supplier!

The lesson to be learned is that it’s worth making sure early on that everyone is fully in agreement with the objectives, outcomes and requirements for the selection. If the new system or service will involve a change in business process or culture, this need becomes even stronger; as this case shows, people may seem to agree on the surface, but the hidden dissent will eventually come out.