Chapter 6

Range of Feelings

This being human is a guest house.

Every morning a new arrival.

A joy, a depression, a meanness, some momentary awareness comes as an unexpected visitor.

Welcome and entertain them all!

Even if they are a crowd of sorrows, who violently sweep your house empty of its furniture, still, treat each guest honorably.

He may be clearing you out

for some new delight.

The dark thought, the shame, the malice.

meet them at the door laughing and invite them in.

Be grateful for whatever comes. because each has been sent as a guide from beyond.

—Jellaludin Rumi

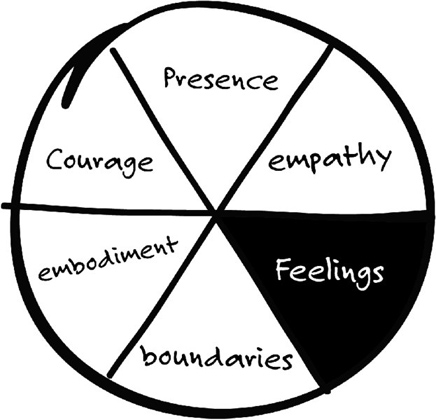

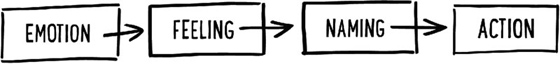

When exploring the terrain of feelings, it is useful to address the distinction between emotions and feelings. They are essentially the same side of a coin with feelings arising from emotions. An emotion is a physiological experience that provides us with data about our world while the feeling is our conscious awareness of the emotion. McLaren’s work on empathy and feelings provides a helpful pathway from empathy to feelings. As shown in Figure 6.1, first an emotion arises, we feel it viscerally, allowing us to name it, and finally, we act upon it.

Figure 6.1 Pathway from Emotion to Action

Our capacity to track physiological cues of an emotion brings a feeling into our conscious awareness, allowing us to name the feeling and, finally, making choices about how we want to act on it or proceed. This path from emotion to action requires mindful attention that we hone over time. When we are caught off-guard and unaware of our physiological cues, we can find ourselves driven by, or even getting hijacked by, a feeling like flying off the handle or losing our cool. When we are able to pay attention to physiological cues like rapid heartbeat, rising blood pressure, warming of the face and neck, we are able to make choices.

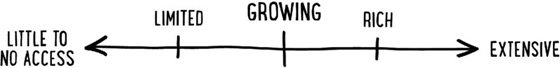

What does a range of feelings imply? It is based on the reality that each of us has access to varying ranges of feelings. Another continuum is shown in Figure 6.2. On the far left, there is little to no access to one’s feelings; on the far right, there is a rich and varied access that acknowledges variations in depth, intensity, and overlapping of feelings. Likely, most of us are somewhere in between these poles.

Figure 6.2 Range of Feelings Continuum

Let’s walk along the continuum and you might start to locate yourself somewhere on it. You might also consider where some of your coachees are on this continuum.

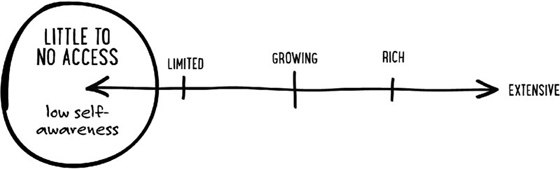

Little to No Access to Feelings

The psychological term for this is alexithymia, from Greek origins meaning a-lex (no words) and thymia (feelings). The term indicates an inability to describe emotional states. The person at this place on the continuum likely has very low self-awareness along with unique challenges in interpersonal connections.

A coach at this spot on the continuum will find it difficult to connect with a coachee enough to form that all-important working alliance because with marginal access to feelings it is harder to notice any feelings in the coachee, as well. In reality, it is very difficult to coach effectively from this spot because a coach needs to imagine the feelings of a coachee to create a strong connection as well as notice feelings as they arise in the coaching. Real change requires a combination of thinking and feeling in our work.

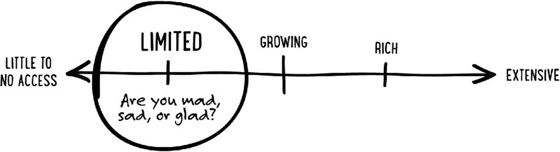

Limited Access to Feelings

The repertoire is small. It may be the three states that are often referenced as mad, sad, or glad. A coach at this spot on the continuum has a limited access and is a step in the right direction. Access to even the rudimentary feelings allows for some connection and working alliance to develop and the coach will be able to sense a baseline of feelings in their coachee. A challenge for this coach is working effectively with leaders who have a broader repertoire of feelings. This coach will likely miss opportunities to notice or sense those feelings and this will diminish the coach’s efficacy.

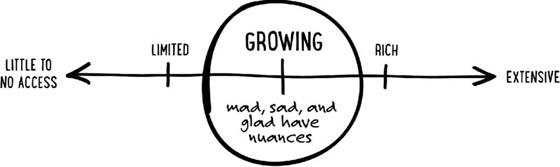

Growing Range of Feelings

The repertoire is broader. Mad, sad, and glad now have nuances and the coach’s feeling vocabulary is enlarged. A coach at this point on the continuum is in an advantageous place, able to build a stronger working alliance, capable of sensing and responding to a wider range of the leader’s feelings. The coach with this growing repertoire of feelings is also able to continue to add to their repertoire with more ease as the language of feelings is more accessible for them.

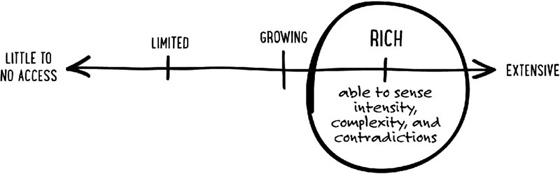

Rich Range of Feelings

The repertoire is nuanced and rich. The coach is able to sense intensity, complexity and contradictions. The coach with a rich range of feelings is able to build a working alliance with ease and attend to a wide range of feelings with varying levels of intensity, overlap, and nuances.

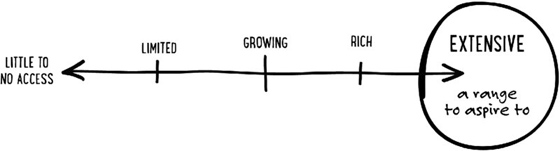

Extensive Range of Feelings

This may be a range to aspire to for all of us and reaching this likely requires one to live a rich life that deliberately engages new experiences and unknown territories and lands. We deepen our range of feelings when we step out of knowing, when we deliberately take some broad leaps into the woods.

Consider these questions to help locate yourself on the feelings spectrum:

- When a coachee sends signals of tearing up in a coaching session, do you stop and explore or keep on topic?

- When a coachee expresses a feeling that is outside of your comfort zone, do you stay there or work to move the conversation in a different direction?

- When a coachee expresses no feelings, do you carry on or stop and see what might emerge?

Culture Matters

While each of us can likely locate ourselves on this continuum and find edges of development that will enhance our capacity as a coach, there is also an important cultural dimension to our repertoire of feelings that we understand as we coach leaders from diverse backgrounds located around the globe. Emotions and feeling are not reactions to the world we live in; rather, our feelings serve as our construction of the world. Lisa Feldman Barrett’s research (2018) on emotions highlights the depth of cultural nuances. Imagine this: the Greeks have a word stenahoria, which means a feeling of doom, hopelessness, suffocation, and constriction. Russians have two ways of talking about what Americans call anger, Germans have three distinct angers, and Mandarin has five. Greeks have two concepts for guilt that distinguish between minor guilts and major guilts (enohi), while Americans have only one. The Dutch culture has an emotion termed gezellig, which translates into comfort, coziness, and togetherness at home with friends and loved ones. Danes have what is now a well-known concept, hygge, for creating a warm atmosphere and enjoying good things in life with good people. The Inuits have no concept of anger and others have no concept of sadness (Barrett, 2018). As coaches, it is helpful to remind ourselves that emotions and feelings are not universal; they are actually constructed and cultivated in one’s culture. Culture wires our brain and is passed on from generation to generation.

DEEPENING YOUR IMPACT: EXPLORING YOUR REPERTOIRE OF FEELINGS

Provoke your brain. Try new experiences and awaken your brain to explore the edges of new feelings and emotions. New experiences can be very simple. The key is trying new experiences regularly to spark your brain. Here are some everyday examples that take little time and few resources:

- Take a walk on a new path you haven’t been on before and notice what you see, what feelings are aroused, what surprises you.

- Stay in a conversation with a stranger a few sentences longer.

- Try out a new food or restaurant, especially those you have nearly no experience with.

- Invite a friend for coffee—a friend with whom you don’t spend much time.

- Read outside of your comfort zone. If you don’t read sci-fi, try it; if you stay glued to nonfiction, try some fiction.

- Try your hand at writing poetry, composing one poem a week for several weeks.

- Watch movies, choosing genres outside of your usual choices.

- Travel to distant lands where you have few, if any, anchors—new language, new landmarks, new customs.

My Internal Landscape: Stories and Stances That Shaped My Range of Feelings

When I step back and review milestones and turning points in my own life, I notice how often the feelings associated with these times are complicated. There is never just one feeling; there are often opposing feelings juxtaposed in ways that increase the richness, the intensity, and the poignancy of the moment. I am the mother of three grown sons and there are so many pivots in their lives that aroused a complex range of feelings. In the earliest years, it was the simple act of saying goodbye in the morning as I left for work and they were held by a caregiver, sobbing as though life would end without me. This experience aroused layers of feelings! Or the moment each left home, a wonderful new step ahead that elicited a lot of pride in their accomplishments. It was a profound territory of emotions in which they were ready to spread their wings and I felt a sadness about the ending of a chapter in our lives. As a leader of an organization, a wife, a mother, and an advocate for a just world, I am blessed with the opportunity to be in many settings focused on a broad spectrum of issues and challenges. I work with leaders who are about to engage in a planned departure from a 30-year career and the contours of the experience are complicated. There is joy about retirement, sadness about letting go of a satisfying career, and fear of the unknown. I work with leaders who find themselves midway through their career with what they believed was a clear path forward, when suddenly, unexpected events result in a restructuring and a loss of their role. In these situations, sadness, anger, disbelief, and more emerges. No matter what the specifics of a major and often unexpected change are, the feelings and reactions are most often complicated and require our ability to explore and contain these feelings in our engagements.

Feelings Are Feelings

Feelings are feelings. There is no positive/negative sort for feelings. Yet, so often the feelings of joy and happiness are viewed as positive ones we ought all to aspire to; these are the feelings for which we are rewarded and praised. Exhibiting feelings of anger, sadness, and grief are often viewed as dark and something we might rather avoid. Every family and every culture has unwritten rules about feelings and as children we learn to adapt in order to flourish or survive in our families and settings. My family was no exception.

Our experiences growing up and the cultural influences of our region in the world influence our range of acceptable emotions, along with the volume and expression of feelings and the levels of intensity allowed when we are children. I grew up on the border of the United States and Canada in the upper Midwest of the country on a cattle ranch and wheat farm. The area was home to mostly second-generation immigrants from Northern Europe, many of whom homesteaded in the area. Winters were long and harsh, large herds of livestock demanded tending no matter what the conditions, seasonal crops required long hours in the fields, neighbors were 100% dependable, and the secret code to surviving and thriving was something like work hard, help others, and don’t complain, for complaint is viewed as a weaknesses and self-sufficiency is an honored strength. I seldom recall my father getting angry and the only time I saw him shed a tear was when a very close friend of his died unexpectedly. Contrast this with a good friend and colleague of mine who grew up as the youngest in a large Italian immigrant family in an urban area of the East Coast. Her parents ran a lively and boisterous Italian family restaurant where people loved and laughed freely, screamed and shouted together, flew off the handle in anger without warning, and let it go just as quickly. All feelings were welcome, modeled, and expected, and all ranges of intensity in expression were a part of her growing up experience. Our access to a range of feelings is impacted by our experience growing up, our work experiences, the cultures of the parts of the globe in which we were raised, as well as the deeply embedded DNA of our heritage.

Our histories seem to give valence to feelings, as well; some are viewed as negative while others are deemed positive. Anger, depression, grief, and sometimes sadness are viewed as negative, and when those around us express these feelings many of us want to encourage the other to look on the bright side, which is code for stop talking about these negative emotions. Happiness, joy, and awe are viewed as positive emotions that are welcomed and good to express in the company of others. Yet, much like the music of a piano, the full range of the keyboard is needed to create music that is complex, rich, and inspiring. We human beings need a full range of emotions to be fully alive. Our times of sadness and grief are woven into the periods of joy and awe in our lives. Each emotion is inextricably connected to another. Anger is the polar opposite of sadness and can help us defend ourselves or serve to motivate us to take active steps to reach an important goal or address a difficult situation. Happiness, or a sense of flourishing, leads to numerous benefits including health, well-being, connectedness, and contentedness.

Feelings Are Human, and So Are Leaders

Feelings, with their wide range of layers and nuances, are a part of the human condition. When a leader comes to a coach, that person brings all of their self to the work and with this comes feelings. This is not the sole territory of psychotherapy; it is the territory of being human. Often coaches shy away from feelings, worrying this may lead to dark, unknown regions of the psyche. Yet, the way in which we reveal and moderate our feelings is core to who we are as human beings. Our feelings prompt many of our actions and our ability to manage our emotional terrain powerfully impacts who we are, how we are experienced by others, and how we operate in the world. Insights that have the potential to change us and create a breakthrough rarely emerge from the intellect alone. Insights that combine thought and emotions stir and inspire us at a much deeper level. Great coaching requires a coach to have facile access to a wide range of feelings and emotional experiences. Without this, we will not be able to meet our clients where breakthroughs occur.

At Hudson, I have spent well over three decades working with leaders who enter into our year-long coaching program in order to develop their capacity to coach others. I have worked with leaders from every sector of our business world and observed a broad spectrum of experiences and access to a range of feelings that these leaders bring to the work of coaching. Some bring a limited repertoire while others have deep capacity in this dimension.

I recall a highly skilled tech leader once telling me that he had three go-to feelings—mad, sad, and glad—and that his capacity to traverse these feelings had served him well throughout his career. In contrast, leaders from other sectors, including organization development (OD) and the likes, often enter coaching with heaps of interpersonal work, T-group training, and experiential facilitation; thus, these individuals often have access to a much broader range of feelings. So, our histories, the cultures of our workplaces, and the nature of our work impacts how easily we access our feelings.

The Range of Feelings Inventory

It stands to reason that many leaders coming to coaching need to devote energy and focus in building a broader repertoire of feelings to do their best work as coaches. I often suggest a good starting place is to take an inventory of the three areas in Table 6.1.

Table 6.1 Range of Feelings Inventory

| Take an Inventory | What Did You Learn? |

| First, make a list of all of your go-to feelings, those you gravitate to with ease and regularity. Track yourself for 7–10 days by jotting a list a couple of times each day. |

|

| Next, spend another 7–10 days taking note of your no-go feelings, those you almost never experience in your day-to-day routines. |

|

| Third, spend some time exploring judgments you have about both your go-to feelings and those on the no-go list. |

|

Once you’ve explored go-to feelings by using this inventory for a few days and noticed the feelings that are your dominant ones, and you’ve also tracked those feelings you almost never experience in your day-to-day routines, you are in a position to consciously cultivate a broader range of feelings. While it’s true that feelings are neutral, we tend to have judgments about specific feelings. Our judgments can often be tracked to our experiences growing up. The simple act of uncovering judgments allows us to access some of the off-limits feelings and grow our repertoire.

For many of us entering the field of coaching, an important part of our work is broadening our access to feelings and our comfort with an expansive range nuanced with intensity and expression.

No One “Makes Us Feel” Anything!

Years ago, I had the privilege of spending a good deal of time with some of the early founders of Transactional Analysis in the United States, Bob and Mary Goulding. My first experience was in the late 1970s, when month-long T-group experiences were standard in many areas of psychology and psychotherapy training. I remember my first visit at Mount Madonna, a ranch-like setting at the top of a mountain overlooking Monterey Bay on the way up the West Coast of California to San Francisco. Eighteen of us, all psychologists or psychotherapists, arrived to experience group learning in Transactional Analysis (TA) group psychotherapy and the power of full immersion over 30 days and 30 nights. With the exception of Sundays, we spent three group sessions each day together exploring our internal landscape. There are many memorable parts to this long-ago experience and one is about feelings. Often in the group people would say, “she makes me feel …” and Bob would bellow out across the room, “Makes you feel? No one makes you feel.” He would go on to elaborate on how our reality is that things happen to us and we have a feeling or we decide we have a feeling, but others can never “make us feel.” I will never forget this learning. It taught me I am in control of my feelings. I am not a pawn of others. I am able to exercise choices about how I want to respond, and how I want to feel about any given situation.

Karla McLaren (2010) offers a tool she terms conscious complaining as a quick practice that yields several helpful results, including learning to recognize and name feelings in order to increase your range of feelings as well as simply expressing feelings in order to cleanse the palette and move on. The practice is a simple one requiring two people—one sharing small complaints and the other listening before exchanging roles. I’ve used this with great success on multiple occasions. Each time people are initially reluctant to engage in complaining, but after just three to four minutes, they are surprised at how many feelings were lingering outside of their awareness and how energized they are to name them and let them go.

My Inner Landscape: What I Learned from Conscious Complaining

I put this practice to work with great success not long ago when I was in the midst of recovering from an accident that resulted in a fracture to my spine. Recovery from a fractured spine is at first painful and eventually, a glacially slow healing process that requires going very slowly for many weeks. It required foregoing all the routines I am accustomed to: full work days, lots of travel, teaching, and lecturing for a day or two at a time in front of a group of participants. For three months, all of my routines had to come to an abrupt stop in order to accommodate complete recovery.

The whole scenario required a dramatically slowed pace. One evening nearly a month into this, a colleague stopped by and knowing this was challenging, wondered if I would find it useful to spend a few minutes engaging in conscious complaining. The exercise is short and to the point: focusing on small complaints of the day. I agreed to give it a try and a long list of complaints unfolded: I can only sleep on my back and I’ve never slept on my back; I can’t bend over so if I drop something I have to ask for help; I need to take naps to help the healing and I’ve always thought naps were for the undisciplined; I can’t drive my car; I can’t exercise for three months; I wish I didn’t have a set of stairs to climb to get to my bedroom; I can’t stand in my kitchen and cook for any length of time; my back is always somewhere between sort of achy and really achy. The list was much longer than I realized and I was surprised by how much better I felt when I acknowledged my list of feelings in the form of small complaints!

DEEPENING YOUR IMPACT: EXPAND YOUR REPERTOIRE OF FEELINGS

Unless you are at the far right of the feelings spectrum, you are probably wondering what one does to build a broader and deeper repertoire. Here are a few practices to build on the previous initial exploration:

- Read, especially memoirs and novels examining the interpersonal domains in depth.

- Check in with yourself regularly and ask, “What feelings have I experienced today?”

- Notice when situations arise and you work to resist or deny feelings.

- Notice when others are expressing feelings, are there some that arouse discomfort in you.

- Take some notes, learn from yourself.

- Watch movies that delve into people’s lives in depth.

- Try two minutes of conscious complaining with someone who will listen and ask you what else.

THE COACH’S WORKSHEET: DEVELOPING MORE RANGE

Visit www.selfascoach.com for an opportunity to step back from each chapter and reflect on what meaning it has for you and what practices you might develop to keep honing your capacity as coach.