7. Predatory and Insider Trading

“The same things happen in all speculative markets.”

—Jesse Livermore

Most financial market prices simply reflect the interaction of supply and demand. It is worth repeating: Most financial market prices simply reflect the interaction of supply and demand. You might not like the message the market is sending—but the price is what it is. There is no conspiracy.

That said, the potential rewards from trading in financial markets can be enormous if one can successfully anticipate price changes. This creates a powerful incentive for every market participant to try to find a trading edge. Most market participants seek only legitimate trading edges and many find none. However, some market participants seek and attempt to exploit illegal trading edges by acquiring access to inside information or engaging in price manipulation.

The nature of these two sources of illegal trading edges is fundamentally different but their impact on other market participants is the same because wealth is transferred. Insider traders exploit an information asymmetry—as traders who possess market-moving information that others don’t have—and profit when the news hits the market. Price manipulators attempt to “make things happen” by triggering a price move in the direction that will generate a substantial profit for themselves. Both entail putting on a security position in advance of the expected price move. Put differently, insider trading attempts to profit from securities that are currently mispriced but will become correctly priced after important information is known by other market participants. Price manipulation attempts to profit from causing securities that are arguably correctly priced to become temporarily mispriced (often by inducing order flow imbalances). The power of price manipulation or inside information (after news comes out) to affect prices depends upon market conditions, sentiment, how crowded or popular trades are, as well as the nature of the news.

This chapter examines the impact of predatory and insider trading on the behavior of financial market prices and assesses the implications for market participants.

Predatory Trading

Price manipulators try to push prices around through large orders, colluding with other traders, spreading rumors, or triggering positive feedback trading. Price manipulation might be preplanned or might arise when opportunities present themselves. More often than not, manipulators try to exploit positive feedback trading—where trading feeds on itself—by setting off stop-loss orders of other market participants or inducing a short squeeze, for example. This type of predatory trading can have a dramatic but usually short-lived impact on market prices. This is especially true for crowded or popular trades. Crowded trades have the potential to set off a wave of selling or buying, thereby exacerbating the price move. Consider the following cases.

Porsche as a Hedge Fund

On October 7, 2008, Volkswagen became the largest automaker in the world in terms of market capitalization as the result of a short squeeze. The price move was exacerbated by the fact that shorting VW in a looming recession sparked by the financial crisis was a popular and crowded trade. (After all, would you expect car sales to increase or decrease during a severe recession?) Shorting requires borrowing shares from another market participant. The prominent investment bank, Lehman Brothers, lent shares to many short sellers. However, Lehman Brothers had, in turn, borrowed VW shares from other market participants, which set off a chain reaction of stock repayment requests and a short squeeze when Lehman failed in mid-September 2008. Bloomberg News reported on October 7, 2008:

“...Volkswagen jumped as much as 55 percent to 452 euros [but] ...erased the gains later to finish 1.8 percent lower at 287 euros...The process may have spurred Volkswagen’s 27 percent jump on Sept. 18, when a recall request would expire under German securities trading settlement periods...”1

Notice the large price surge and the transient nature of it. VW closed down for the day. Trading volume on October 7 was more than four times the volume on October 6 and more than seven times the trading volume on October 5. One of the reasons was that the trade was “crowded” (many traders were short VW shares). However, the price action in VW stock did not end there. Also, although the short squeeze in VW shares was triggered by the collapse of Lehman, it likely would have been triggered later—as subsequent events showed. The article conjectured that a large jump in VW’s stock price on September 18 might also have been related to short covering following Lehman’s collapse on September 15.

Common stock represents a claim on the residual assets of a firm, future dividends, and the right to vote on corporate matters. Many hedge funds put on a more complex trade than simply shorting VW common stock. Instead, these hedge funds shorted VW common and bought VW preferred shares in the belief that the value of the voting rights on VW common stock would decline as Porsche’s fraction of ownership of VW increased. These traders were betting that the spread, or difference between the price of VW common and preferred shares, would decrease. The trade did not converge as expected. Instead it widened as the price of VW common rose and the price of VW preferred stock declined.2 Shorts lost on both legs of their spread trade—the preferred stock they were long declined and the common stock they were short rose sharply in price.

The situation got even worse for the shorts. On Sunday, October 26, 2008, Porsche announced that it was increasing its stake in VW to almost 75%. Even if 25% of shares were still available to trade, the shorts would have faced serious losses. However, 25% of shares weren’t available. That’s because the state of Lower Saxony held a 20.1% stake in Volkswagen—a stake it was highly unlikely to part with anytime soon, which theoretically left about 5% of shares available to trade. This is theoretically because it was just that. Some holders of VW stock (such as index funds) could not sell their shares.3 In a mad rush to cover their short positions, traders around the world bid up the price of VW stock.

Bloomberg News reported on October 28, 2008 that Volkswagen briefly became the largest company in the world in terms of market capitalization after it...

“...rose as much as 485.01 euros, or 93 percent, to 1,005.01 euros and was up 55 percent as of 11:10 a.m. in Frankfurt trading...”4

This was a huge move—but it could have gone even higher had the overall short position been as large as it was before the earlier short squeeze(s) triggered by the collapse of Lehman Brothers. The article pointed out that short interest stood at almost 13% of total shares outstanding (or about 15% less than on October 7). So why was there still significant short interest in VW? Prior to Porsche’s announcement, there was some reason for optimism among traders who were short because VW shares bounced around from the October 7 surge noted earlier and fell 23% on October 20, 2008.5 In addition, the short squeeze triggered by the unexpected collapse of Lehman Brothers was over.

In the midst of the greatest financial crisis in generations, a looming worldwide recession, and extreme uncertainty, panic buying meant that VW overtook Exxon as the most valuable company in the world.

But just how was Porsche able to largely conceal its effective acquisition of a majority of VW stock from the market as a whole?

Part of the reason for the large impact of Porsche’s announcement on the price of VW common stock was that Porsche’s call option position on VW shares was unknown to most traders. Under German law cash-settled options did not need to be publicly disclosed. The purchase of call options also helped push VW’s share price up as who sold the options to Porsche presumably hedged themselves by buying VW stock on a delta neutral basis (such that the value of their position was unchanged for small changes in the price of the stock).6 As the price of VW stock rose, the banks needed to purchase more shares to remain hedged. This is an example of positive feedback trading. Porsche presumably knew this would—or could—happen, and had every incentive to keep buying more call options.

The option transactions were very profitable for Porsche. Over the six months from August 1, 2008 through January 31, 2009, Porsche made €6.8 billion from its VW investment—far more than from its sales of automobiles during the same period.7 Indeed, a similar story can be told for 2007 where Porsche earned €3.6 billion from its financial transactions or three times what the company made from selling automobiles according to the Financial Times.8

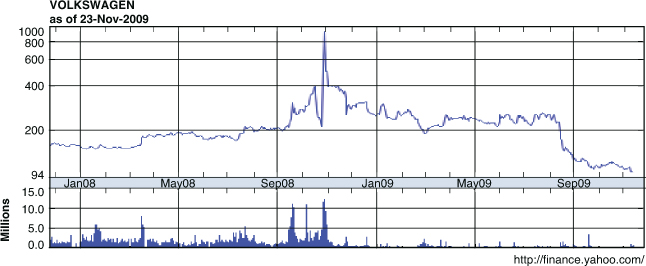

The flip side of the Porsche profits was the losses suffered by the shorts. Many of the shorts were hedge funds. However, one short was German billionaire, Adolf Merckle, at one point one of the richest individuals in Germany. Unfortunately, the stunning losses on his VW short position coupled with margin loans called on some of his other investments caused him to commit suicide on Monday, January 5, 2009.9 A federal judge in New York who ruled that U.S. courts lacked jurisdiction in the case dismissed a lawsuit against Porsche by hedge funds that claimed $2 billion in damages.10 The hedge funds that filed the suit against Porsche then filed a suit in a New York State court. This suit was later dismissed in December 2012, and the hedge funds involved agreed not to appeal the ruling.11 Figure 7-1 shows the behavior of Volkswagen’s stock price during 2008.

(Reprinted with permission from Yahoo! Inc. 2013 Yahoo! Inc. [YAHOO! and the YAHOO! logo are trademarks of Yahoo! Inc.])

Figure 7-1. This chart depicts the behavior of VW’s stock price when it briefly became the largest company in the world in terms of market capitalization as the result of a short squeeze.

The Porsche-VW saga is interesting from several perspectives. The first short squeeze occurred by chance due to the unexpected failure of Lehman Brothers. The second short squeeze appears to have been a predictable consequence of the actions that Porsche took in acquiring its option position. Although the events that precipitated the changes differed, the power of positive feedback trading was apparent in both short squeezes. The Porsche-VW saga illustrates the game-like nature of trading.

Whales in Trouble

Large traders are sometimes referred to as “whales” given the large positions they hold and sometimes the size of their trades. These large positions are often difficult to get out of quickly without impacting market prices. “Whales in trouble” refers to large traders who have substantial losses on their position and are forced to exit one or more security positions quickly, thus exacerbating their losses.

A Second Stock Market “Crash”

On October 19, 1987, the U.S. stock market crashed when the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell 23%. The carnage was even worse in the futures markets where the S&P stock index futures fell 29%. Like the stock market crash of October 28–29, 1929—where the market fell more than 24%—the October 19, 1987 stock market crash is well known.

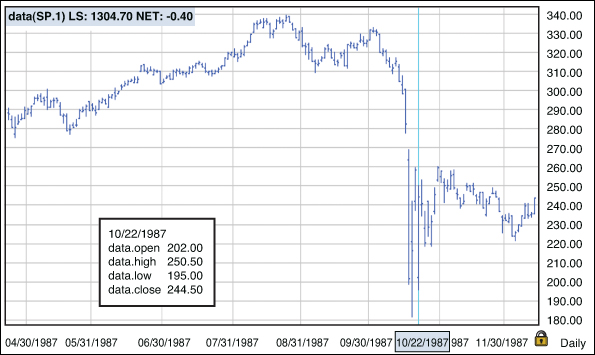

Fewer people are aware that a second equity market crash essentially occurred in the States a few days later in October 1987. A second effective “crash” occurred on Thursday, October 22, 1987 in the S&P 500 stock index futures market when it opened more than 23% lower—roughly the amount of the cash stock market crash a few days earlier.

The December 1987 delivery S&P 500 stock index futures contract had closed at 258.25 on Wednesday, October 21, 1987. A number of rumors swirled around the S&P 500 stock index futures market before it opened on Thursday morning, including the rumor of a large trader (supposedly George Soros) in trouble. Every market always has two prices—the bid and the offer. A broker offered to sell 5,000 contracts at the open at a price of 230 per contract. At the time, the S&P 500 futures contract was traded in the pits with a minimum tick value of $25 and a full-point move equal to $500. The offer to sell at 230 was tantamount to a $14,125 discount from the previous day’s closing price per contract. There were no takers. Imagine you were a local in the S&P 500 stock index futures pit on the floor of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange that morning. Would you take the offer of someone desperate to sell? Or would you force them to hit your much lower bid price? There were no takers at 220 or 210 either. Finally, the market opened in an unbelievably wide 7-point range—tantamount to $3,500—from 195 to 202 or some $31,625 lower than Wednesday’s closing price. After the position was sold at a huge discount, the market bounced most of the way back—closing at 244.50. The November 2, 1987 issue of Barron’s recounts the action:

“...The [downward] spiral was ghastly. It was Soros’s block and not program trading that drove the futures to a cash discount... [of] 50 points, or 20%...”12

The Barron’s article suggests that Soros suffered a loss in excess of $200 million. Again, the cause of the decline was simply the market’s response to a large 5,000-contract sell order amid rumors of a large trader (allegedly George Soros) in trouble. There was no fundamental information. The decline and subsequent rally was entirely trader induced. In this case, it was traders taking advantage of a large trader in trouble. Figure 7-2 shows the size of the price drop.

Figure 7-2. This chart shows the sharp change in S&P 500 stock index futures prices that occurred during October 1987.

Aside from showing the sometimes-cutthroat nature of trading, this example also underscores the fact that algorithmic and high frequency traders HFTs aren’t the only ones who can take advantage of large orders—humans have been doing this for years.

The Yen Suddenly Rises

As the previous example demonstrates, large traders in trouble might trigger sudden sharp price changes if other market participants believe that they will be forced to quickly unwind their positions. On October 7, 1998, the dollar fell sharply against the yen. At one point during the day, it was down 12 yen or about 9.15%—an incredible intraday move for two major currencies from developed countries. Again, there was no fundamental news. Indeed, the Bank of Japan was worried about the sudden rise in the value of the yen. The move was entirely trading induced. Contemporary news accounts attributed the decline to unwinding of yen carry trades. There were also rumors that two large hedge funds, LTCM and Tiger Management, had substantial short yen positions that they were forced to cover. The New York Times described the move in the dollar/yen exchange rate as follows:

“The dollar plunged 8.1 percent against the Japanese yen... [as] hedge funds and other investors [rushed] to get out of bets against the Japanese currency...”13

In the VW example, sharp increases in the price of VW common followed forced short covering by many traders. The previous two examples demonstrate how forced covering of bets of one or more large traders can precipitate large increases in prices. Again, there was no fundamental reason for it. The rise was simply trading induced.

The Amaranth Trading Debacle

Amaranth was a multi-strategy hedge fund whose holdings were dominated by its energy trading positions. It earned substantial profits from energy trading during 2005. However, in 2006 it held a large spread trade position in natural gas. Simply put, it was long and wrong the March 2007–April 2007 natural gas spread. The spread narrowed by $1.39 in two weeks with more than $1 of the decline occurring after the market learned that Amaranth was in trouble. According to a September 19, 2006 article in Bloomberg Businessweek:

“...The 64% drop in the spread...began slowly...but came crashing down by more than $1 per MMBtu in the past three trading days.”14

Put differently, most of the $1.39 decline in the spread (and hence trading loss) came after Amaranth was identified as a large trader in trouble. Arguably, a substantial part of the change in price was trading-induced as opposed to being the result of the arrival of new fundamental information.

SocGen

Sudden, sharp, trading-induced price changes have always existed in markets and have seemingly become more frequent. They impose additional risks on traders and might mislead policymakers. For instance, contemporary news accounts indicate that convicted rogue trader Jerome Kerviel’s losses at Societe Generale were about €1.4 billion when discovered in January 2008 and €4.9 billion after his positions were covered. SocGen lost an additional €3.5 billion unwinding the rogue trading positions because the market sensed a large trader was in trouble. It is possible that some collateral damage resulted from the Kerviel affair—namely, the resulting sharp decline in European equity prices might have spooked the Federal Reserve into making a surprise 75-basis-point cut in the targeted Fed funds rate on January 22, 2008.

The potential for positive feedback trading provides policymakers with a means of magnifying the impact of policy actions by igniting short-covering rallies or other instances of positive feedback trading. This means that sometimes these strategies can be used “for good” (to induce rallies). For example, the coordinated action by the Fed and five other central banks on November 30, 2011 to increase dollar liquidity sparked a short-covering rally in equity prices in major markets around the world.

JP Morgan’s “London Whale”

The size of the multibillion dollar loss suffered by JP Morgan in April and May 2012 undoubtedly reflects, in part, market participants taking advantage of a large trader in trouble. Bloomberg News reported on May 14, 2012 that a JP Morgan Chase credit derivatives trader:

“...has amassed positions so large that he’s driving price moves in the $10 trillion market...The trader may have built a $100 billion position in contracts on... [one index] ....”15

It should be emphasized that the individual was not a rogue trader because the positions were approved by his superiors.

One lesson about markets is that rarely is one trader bigger than the market. Put differently, rarely can a single trader push prices around for long periods of time. Convicted rogue trader, Nick Leeson, tried to do it at Barings in 1995 and failed. The “London Whale” was no exception. This trader soon experienced substantial losses, which were exacerbated as other traders recognized and tried to take advantage of a whale in trouble:

“Signs are emerging that traders are already attempting to squeeze JPMorgan Chase (JPM) after ... [it] said it faced $2 billion in trading losses related to credit derivatives...”16

Not surprisingly, the initial $2 billion trading loss (which was initially attributed to “hedging”) was revised upwards to more than $6.2 billion.17 When trading, being an 800-pound gorilla has its advantages, but being an 800-pound gorilla can also make you vulnerable.

A report by a task force created by JP Morgan Chase Board of Directors to examine the incident makes interesting reading.18 The report concludes that the massive loss was:

“... the result of a number of acts and omissions, some large and some seemingly small, some involving personnel and some involving structure, and a change in any one of which might have led to a different result.”19

The Report notes the failure of relevant management to address repeated concerns expressed by the traders involved about potential losses on the bank’s massive credit derivative positions.20 The Report notes that some concerns were expressed as early as December 2011. To his credit, an unidentified trader apparently tried to convince his superiors at the bank to stop increasing the size of the position and take losses in January 2012, but was not allowed to do so.21 If true, the refusal of this trader’s superiors to allow him to cut his losses short helped create a whale in trouble.

It Only Takes a Moment

Sometimes the trading objective is to push prices momentarily in order to affect the closing price. The closing price may determine whether a trade is a winner or a loser. Such was apparently the motivation in a case against Mr. Rameshkumar Satyanarayan Goenka according to the Financial Services Authority in the United Kingdom. The FSA ordered him to pay a “financial penalty” of $6,517,600 and restitution of $3,103,640 to the counterparty to his trade.22 The FSA contended that:

“Mr. Goenka placed orders to trade which artificially inflated the closing price of Reliance GDRs, an instrument traded on the International Order Book of the London Stock Exchange, on 18 October 2010. Mr. Goenka arranged for a series of substantial and pre-planned trades in those securities to be executed in the final seconds of the LSE closing auction. The orders were placed with the intention of increasing the closing price for Reliance GDRs above a certain level. At the time, Mr. Goenka held a structured product on which the pay-out depended on the closing price of Reliance GDRs that day. By increasing the closing price, Mr. Goenka was able to avoid a loss of USD 3,103,640 under the terms of the structured product.”23

Although Mr. Goenka paid the financial penalty, he denied any wrongdoing. His lawyer argued that Mr. Goenka did not engage in market abuse but was simply lawfully “hedging a position on which he was running a significant risk.”24

Speculative Attacks—“If at First You Don’t Succeed...”

Convicted bank robber Willie Sutton allegedly answered the question of why he robbed banks by saying, “That’s where the money is.” Something similar might be said of why currencies are sometimes attacked. By trying to maintain an exchange rate that often cannot be maintained, central banks create potential trading opportunities. They also allow traders to do size by taking the other side to trades that other market participants might not and create skewed payoffs in the process. If the central bank is successful in maintaining the peg the speculator loses a little by shorting the currency. If the central bank fails to maintain the peg, the speculator gains a lot. These are the proverbial one-sided bets that traders covet.

The Hong Kong dollar is linked to the U.S. dollar under a currency board arrangement. At the time of the Asian Financial Crisis, the fixed exchange rate was HK$7.80 to US$1.00. The currency board system is a passive monetary system. New Hong Kong dollars are created when additional U.S. dollars enter the banking system and destroyed when they exit the banking system. Interbank interest rates are a function of the total balance of funds held by the Hong Kong clearing banks at the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA)—the de facto central bank of Hong Kong. The sudden dumping of a large amount of Hong Kong dollars will reduce the aggregate balance and raise the interbank interest rate sharply. The rise in interest rates might precipitate a decline in stock prices.

On July 2, 1997, Thailand devalued the baht against the U.S. dollar. A currency crisis soon spread to Malaysia and Indonesia. Even Singapore devalued its currency against the dollar. The currency crisis soon spread elsewhere in Asia. The Hong Kong dollar came under attack. Webb [2007] described the attack in detail.25 Hedge funds started selling large amounts of Hong Kong dollars in an attempt to break the link with the U.S. dollar. As expected, interest rates rose and stock prices fell sharply. On Monday, October 27, 1997, volatile stock prices in Hong Kong spilled over to the U.S.A. when the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell more than 500 points, or over 7%. U.S. equity markets recovered most of that lost ground on Tuesday, October 28, 1997. The episode stopped when the hedge funds ran out of Hong Kong dollars to sell and could not borrow anymore. The link between the Hong Kong dollar and the U.S. dollar held. The currency board system worked.

However, the cost to Hong Kong came in the form of a period of high interest rates and volatile stock prices. The hedge funds that shorted the Hong Kong dollar had lost but learned two lessons from their failed speculative attack on the Hong Kong dollar:

• Get a larger amount of Hong Kong dollars to short before trying to break the peg.

• Substantial profits could be made from a speculative attack on the Hong Kong dollar (even if the link held) by shorting the stock or stock index futures market.

The hedge funds solved the first problem by borrowing HK$30 billion in the currency swap market. This gave them plenty of Hong Kong dollars to sell. It would also prevent them from having to pay sharply higher interest rates on Hong Kong dollars that were borrowed after the attack was under way. They solved the second problem by shorting Hang Seng stock index futures contracts in advance of the attack. They had prepared for full-scale financial warfare against the HKMA. After borrowing billions, they were now ready to lead another attack on the Hong Kong dollar. The cost was the carrying cost for borrowing HK$30 billion. Joseph Yam, Chief Executive of the Hong Kong Monetary Authority at the time described it this way:

“A few figures will help give some idea of the scale of this attack...We estimate that the hedge funds involved had amassed in excess of HK$30 billion in currency borrowings, at an interest cost of around HK$4 million a day. They also held an estimated 80,000 short contracts, which translated into the following calculation: for every fall of 1,000 points in the Hang Seng index they stood to make a profit of HK$4 billion. If they could have engineered that fall within 1,000 days they would have broken even. If they could have achieved it within 100 days they would have netted HK$3.6 billion. All they had to do was to wait for the best moment to dump their Hong Kong dollars, to drive up interest rates and send a shock wave through the stock market...”26

The Hong Kong Monetary Authority recognized the speculative attack for what it was and took the unusual step of intervening in both the cash stock market and stock index futures market to counter the hedge funds. With strong decisive action, they were able to inflict substantial losses on the hedge funds to discourage similar behavior in the future. They were so successful that their intervention in the cash equity market also ultimately proved to be profitable for the HKMA.

LIBOR

The Chicago Mercantile Exchange lists several interest rate futures contracts, including the three-month Eurodollar futures contract. The Eurodollar futures contract offers market participants an opportunity to speculate on, or manage their risk exposure to, the three-month LIBOR (London Interbank Offered Rate). The CME Eurodollar futures market is the largest interest rate futures market in the world, often trading one to two million contracts per day. Given that each contract has a notional principal of $1 million, that amounts to $1–$2 trillion per day. The size of the daily trading volume alone suggests that manipulating this market would be difficult. The potentially weak link in the armor is that the contract assumes no collusion among banks in determining the settlement price. The contract is settled at the average of a survey of leading banks with respect to their three-month LIBOR quote with the highest and the lowest rates discarded. Unfortunately, it appears that some of the major banks that the CME relied on to provide honest assessments of three-month LIBOR might have adjusted their quotes up or down to profit from it in their trades. Barclays was the first major bank to settle charges and paid a $450 million fine for its role in trying to manipulate LIBOR. The Financial Times reported on June 27, 2012:

“The Barclays settlement is the first shoe to drop in a sprawling probe that...now spans nearly a dozen regulators and more than 20 banks....”27

UBS paid a fine of almost $1.5 billion for its role in the LIBOR and Euribor rate fixing scandal.28 Unlike the earlier examples of predatory trading, the LIBOR rate fixing scandal did not require positive feedback trading to obtain the desired price. Moreover, to most market participants, there was no discernible market shock. However, like the previous examples of market abuse, the LIBOR rate fixing scandal damaged the integrity of the market and the credibility of market prices.

Gunning for Stops

In days gone by, the pit community used to be accused of gunning for stops—trying to unleash a wave of orders in one direction to temporarily push prices around. One way to prey on traders is gunning for stops. Although much High Frequency Trading (HFT) activity is geared toward market making, some HFT algorithms are predatory in nature.

Gunning for stops means either buying or selling a security with the goal of pushing it toward a certain price where stop loss orders are clustered. The idea is to trigger the stops in order to profit from temporary price distortions that may arise when a large amount of stops are set off.

Traders tend to put stops to buy or sell at certain breaking points, some of which can be predicted. Some are easy to predict, because they tend to be around key technical support or resistance levels. Some are not. For example, the Dow Jones Industrial Average set a high of 14,164 on October 9, 2007. Many technicians will regard 14,164 as a key resistance level that might be tested by the market multiple times. If the level is broken (by more than a little bit), it will signal sharply higher prices. Traders who are short the market might set stop-loss orders to buy (with buy stop orders) slightly above the 14,164 level.

However, if traders can predict a set of stops, they may be able to make money by setting off those stops. Buy stops are often set above a commonly perceived resistance level due to the possibility of “false breakouts” triggered by other traders attempting to set off stops. False breakouts occur when the resistance (support) level is only temporarily broken before returning below (above) it.

So if one predicts that there are a large number of orders to buy a stock at $20, with the price currently at 19, one needs to push the price up (by buying shares or spreading rumors, for example) until the stops are set off at 20. Assuming there are a large number of buy stops at 20, these stops will then set off an automatic cascade of buying, pushing prices temporarily even higher and enabling the trader to take a nice profit. Put differently, if buy stops are clustered at a given price, pushing prices to that price may set off positive feedback trading, which causes prices to temporarily move higher.

Informed Trading

On April 29, 2008, the Financial Times reported that the Financial Services Authority (FSA) contended that 28.7% of all mergers deal announcements in the U.K. “were preceded by “informed price movements” [in 2007], up from 23.7 percent in 2005.” The FSA report argued that there were two types of informed trading: “legitimate,” which arose in 10% of merger deal announcements and “abnormal,” which arose in 18.7% of deal announcements. The latter category included insider trading. Assuming that the same proportion of merger deals involve insider trading in the U.S. as in the U.K., this means that the SEC should have substantially more insider trading prosecutions from merger deals alone. Yet, the SEC initiated only 50 insider trading cases from all sources during 2007. The SEC website points out that the Agency “brought 57 insider trading actions in FY 2011 against 124 individuals and entities, a nearly 8 percent increase in the number of filed actions from the prior fiscal year.”29 Why not more? Are the only ones prosecuted for insider trading the unlucky and the dumb?

Puts on Bear Stearns

Chapter 2, “Five Simple Questions,” discussed the collapse of Bear Stearns in March 2008. The sharp decline in its stock price on Friday, March 14 and its forced sale over the weekend to JP Morgan Chase (initially for $2 per share and later revised upward to $10) precipitated a large selloff in financial stocks on Monday, March 17, 2008. Fortunes were made by those who had shorted Bear the week before while fortunes were lost by those who were long Bear over the weekend.

Another bizarre, and, if true, deeply troubling dimension exists to the Bear Stearns saga involving trading in deep out-of-the-money Bear Stearns put options. The Chicago Board Options Exchange (CBOE) listed puts on Bear Stearns with a 30 strike and March 2008 expiration. Forty strike puts on Bear also were being traded. Anyone who purchased puts on Bear before it went under reaped enormous percentage gains. Given that the stock was trading in the low 60s at the time the probability that a major company would lose one-third to one-half of its value in a few days was close to zero, this made purchasing the options very cheap but also akin to buying lottery tickets. Buying a few lottery tickets can be fun but most people would not invest hundreds of thousands of dollars on such a bet. Yet, someone did just that if an academic study by Chesney et al [2012] is correct. In an interesting and provocative study, Chesney et al [2012] argue that informed trading in deep out-of-the-money put options preceded the collapse of BSC. They note that open interest for the March 30 put increased substantially on March 10 and 11, 2008 and the subsequent exercise of the March 30 puts led to “net gains of more than $50 million.”30 They state:

“On March 17...the stock dropped nearly 85% to $2.86, increasing the value of these put options to $27.14.”31

Chesney et al [2012] examine a number of other instances of seemingly informed trading in put and call options in advance of similar events.

To be sure, the fact that the puts were profitable does not necessarily mean that there was a grand conspiracy to put Bear Stearns out of business or that the purchasers of the puts knew that Bear would be forced to sell to JPMorgan Chase at a firesale price. It is possible that the purchasers of the puts may simply have believed that Bear’s ability to fund itself in the repo market would deteriorate rapidly and with it its stock price. As discussed in Chapter 10, “Flight to Safety,” the rapid rise in the credit default swap rate for Bear before its collapse would suggest so. That said, the purchase of so many put options that would have expired worthless under most scenarios would have been regarded as a bad trade by many traders before Bear’s collapse, so this episode remains unsettling. It would be interesting to ascertain whether any of the purchasers of the puts were traders at other institutions who regularly provided Bear with funding via the repo market.

Dow Jones & Company Stock

Consider the following example of trading in Dow Jones & Company (DJ) stock and stock options during April 2007. Dow Jones & Company was a lackluster stock. On April 25, 2007 call option volume in DJ suddenly surged with 3,029 contracts traded versus a maximum of 728 calls for any previous trading day in April 2007. This compared with a 20-day average trading volume of 309 calls. On April 30, 2007, 4,335 calls traded. September 45 calls were the most active with 3,464 calls traded between 30 and 40 cents per share during the last 11 minutes of trading.

At 11:13 a.m. on May 1, 2007, the financial press reported that News Corporation was in talks to acquire DJ for $60 per share. The unsolicited bid represented an almost $23 premium over the opening price of $37.12. Not surprisingly, news of the expected bid put the stock in play and the price shot up to $57.28 before closing at $56.20 per share. The price of the September 45 call options soared to more than $14.50 on May 1, 2007 after reports broke of News Corp.’s $60 per share bid. The September 45 calls closed at $12.

Less than a week after the May 1, 2007 announcement, the SEC charged a married couple from Hong Kong with insider trading. The couple bought almost 415,000 shares in DJ in the two weeks preceding the announcement. The couple sold their stock for an $8.1 million profit on May 4, 2007.

Subsequent investigations revealed that David Li, a Hong Kong–based director of Dow Jones & Company, had disclosed the planned bid to a friend, Michael Leung, who disclosed the inside information to his daughter, Charlotte Wong Leung and son-in-law, Kan King Wong. In early February 2008, the SEC obtained a settlement: David Li—$8.1 million fine; Michael Leung—$8.1 million fine plus $8.1 million profit disgorgement; K.K. Wong—$40,000 fine plus $40,000 profit disgorgement.32 No one admitted wrongdoing. All the trades were in the cash equity market. Yet, to date there have been no known prosecutions for insider trading in DJ calls before news of the announcement. Who bought the DJ call options?

Trading Lessons

Most traders put on positions in the hope that prices will move in the direction that will make their trades profitable. Predatory traders put on positions and attempt to push prices in the direction that will make their trades profitable. Although most prices are determined simply by the interaction of supply and demand, the examples in this chapter demonstrate that predatory trading sometimes occurs. Some of it is opportunistic as traders go in for the kill when a large trader is in trouble. Traders eat their own kind. Some of it is premeditated, such as the speculative attacks on currencies. The impact on prices is often large but transient. If positive feedback trading can be ignited by setting off stop-loss orders, margin calls, or dynamic hedging transactions, the effects of predatory trading on market prices can be magnified. Sometimes the actions of predatory traders can exert substantial collateral damage, as was apparent in the impact of the speculative attacks on the Hong Kong dollar in 1997 and 1998 where local interest rates and stock prices in Hong Kong and the USA were affected.

The collapse of firms such as Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, AIG, FNMA, and Freddie Mac has been accompanied by widespread derision of the executives who once ran these firms. Many of these same executives were widely praised for their management prowess before the Global Financial Crisis. To be sure, the executives have blame to bear. In many cases, too much risk was borne by these firms. However, other market participants (including, in some cases, the regulators) often lent a helping hand in precipitating the collapse. Also, although not destitute after the collapse of their firms, many of these same executives lost large personal fortunes that were tied to the success of their firms.

The history of financial markets, like all history, is written from the perspective of the winners or, at least the survivors. A natural tendency exists to vilify, ridicule, or deride the decisions and actions of those executives whose companies collapsed. It makes understanding what occurred easier but it also distorts what actually happened. The errors of policymakers are often glossed over or ignored. This is unfortunate because it obscures what actually happened in the run up to the collapse or in the immediate aftermath. Understanding what actually happened is important in order to appreciate the trading opportunities and risks associated with such events. The Global Financial Crisis that began in 2007 is no exception.

The illegal exploitation of inside information remains a problem in financial markets. Market participants should expect it to persist. We live in an imperfect world and no one can compete against inside information, especially during a crisis.

Some of the largest changes in speculative prices often have little to do with the arrival of new fundamental information or noise trading. Instead, they represent predictable behavior by profit-maximizing traders taking advantage of transient profit opportunities or flawed market microstructure. In an interesting academic study, Carol Osler and Tanseli Savaser [2009] argue:

“...price-contingent trading is potentially a major source of extreme returns without news...[and] could be an important source of excess kurtosis in financial returns.”33

This means that traders should not look only at potential news events to find catalysts for large price moves. Some of the largest price moves might be trading induced through positive feedback trading.

On the flip side, actions of speculators are often blamed for precipitating or at least exacerbating the financial crisis. Much of this blame is misplaced. In most cases, short sellers are merely conveying relevant information to the market. Anyone looking for white knights on white horses in the field of finance should plan for a long search.

Endnotes

1. Xydias, A., “Volkswagen Can Thank Lehman, Hedge Funds for Gains.” Bloomberg News, October 7, 2008. http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=aPGIxA0kTzl8&refer=home.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6. Delta gives a measure of how much the price of the call option would move for a €1 change in the price of the underlying stock. A delta of .50 would mean that owning 50 shares of VW would be enough to hedge a call option that gives the holder the right to buy 100 shares of VW at the agreed exercise price. The absolute value of delta is akin to the probability of exercise. As delta rises, the bank would need to buy more stock as exercise becomes more likely. However, the purchase of VW stock by the banks that sold the options might push up the price of VW shares even more leading to even more purchases of VW stock by the banks to remain hedged.

7. Wiesmann, G., “Volkswagen Windfall Gives Porsche Fourfold Lift.” Financial Times, April 1, 2009. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/01e2f1ac-1e57-11de-830b-00144feabdc0.html#axzz2Cv4vwN8l.

8. Lex, “The Speedy Option.” Financial Times, October 22, 2008. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/66387882-9fd3-11dd-a3fa-000077b07658.html#axzz2Cv4vwN8l.

9. Wilson, J., “Spirit of Risk that Led to the Rise and Fall of Merckle Empire.” Financial Times, January 7, 2009. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/4c94ed8e-dc5a-11dd-b07e-000077b07658.html#axzz2Cv4vwN8l.

10. Ahmed, A., “Judge Dismisses Hedge Funds’ Case Against Porsche.” New York Times, December 30, 2010. http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2010/12/30/judge-dismisses-hedge-funds-case-against-porsche/.

11. Frankel, A., “Hedge Funds Dodge Morrison in State-Court Case Against Porsche.” Thomson Reuters news & Insight, August 9, 2012. http://newsandinsight.thomsonreuters.com/Legal/News/2012/08_-_August/Hedge_funds_dodge_Morrison_in_state-court_case_against_Porsche/.

Dolmetsch, C., “Porsche Says Funds Decide Against Appealing N.Y. VW Case,” Bloomberg News, February 1, 2013. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-01-31/porsche-says-funds-agree-to-end-new-york-court-suit.html

12. Barron’s, “A Bad Two Weeks—A Wall Street Star Loses $840 Million.” November 2, 1987.

13. Fuerbringer, J., “The Markets: Currencies; Dollar Drops 8% in Day Against Yen.” New York Times, October 8, 1998. http://www.nytimes.com/1998/10/08/business/the-markets-currencies-dollar-drops-8-in-day-against-yen.html.

14. Holland, B., “Are There More Amaranths Lurking?” Bloomberg Businessweek, September 19, 2006. http://www.businessweek.com/stories/2006-09-19/are-there-more-amaranths-lurking-businessweek-business-news-stock-market-and-financial-advice.

15. Ruhle, S., B. Keoun, and M. Childs, “JPMorgan Trader’s Positions Said to Distort Credit Indexes.” Bloomberg News, April 6, 2012. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-04-05/jpmorgan-trader-iksil-s-heft-is-said-to-distort-credit-indexes.html.

16. Childs, M. and S.D. Harrington, “JPMorgan Losses Spark Frenzy in Swaps Indexes: Credit Markets.” Bloomberg News, May 14, 2012. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-05-14/jpmorgan-losses-spark-frenzy-in-swaps-indexes-credit-markets.html.

17. McLaughlin, D., “JPMorgan Turned CIO into Prop-Trading Desk, Pensions Say.” Bloomberg News, November 21, 2012. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-11-21/jpmorgan-turned-cio-into-prop-trading-desk-pensions-say.html.

18. JP Morgan Chase, “Report of JPMorgan Chase & Co. Management Task Force Regarding 2012 CIO Losses.” January 16, 2013. http://investor.shareholder.com/jpmorganchase/events-files.cfm.

19. Ibid.

20. Ibid.

21. Gimen, M., “From the Belly of JPMorgan, a Closer View of the Whale Trade,” Bloomberg News, January 16, 2013.

22. FSA, Final Notice, October 17, 2011. http://www.fsa.gov.uk/pubs/final/rameshkumar_goenka.pdf.

23. Ibid.

24. Fortado, L., “U.K. FSA Fines Dubai Investor Goenka Record $9.6 Million.” Bloomberg Businessweek, November 10, 2011. http://www.businessweek.com/news/2011-11-10/u-k-fsa-fines-dubai-investor-goenka-record-9-6-million.html.

25. Webb, R., Trading Catalysts—How Events Move Markets and Create Trading Opportunities, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: FT Press, 2007.

26. Joseph Yam, Hong Kong Monetary Authority, “Coping with Financial Turmoil.” Inside Asia Lecture 1998, Sydney, Australia, November 23, 1998.

27. Masters, B. and C. Binham, “Barclays Fined a Record £290 M.” Financial Times, June 27, 2012. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/2a4479f8-c030-11e1-9867-00144feabdc0.html#axzz2Cv4vwN8l.

28. Ridley, K. and S. Slater, “Lawsuits Cast Darker Shadow Over Banks than Fines.” Reuters News, December 21, 2012. http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/12/21/us-banks-libor-lawsuits-idUSBRE8BK0OF20121221.

29. Securities and Exchange Commission, SEC Enforcement Actions, Insider Trading Cases—accessed November 17, 2012. http://www.sec.gov/spotlight/insidertrading/cases.shtml.

30. Chesney, M., R. Crameri, and L. Mancini, “Detecting Informed Trading Activities in the Options Markets: Appendix on Subprime Financial Crisis.” (July 3, 2012). Swiss Finance Institute Research Paper No. 11-38. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1931639 and http://ssrn.com/abstract=1931639 or http://dx.doi.org/102139/ssrn.1931639.

31. Ibid.

32. Scheer, D., “David Li Settles with SEC in Dow Jones Trading Case, People Say.” Bloomberg News, February 2, 2008. http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=acMxQvDFPCXM&refer=home.

33. Savaser, T. and Osler, C. L., “Extreme Returns without News: The Case of Currencies.” (February 16, 2009). Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1344854 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1344854.