7. Rock Shrimp and Spotted Prawns

Anything humans can’t use, or understand, they label as trash. For years scientists called the parts of the genome that appeared to do nothing “junk DNA” before they discovered how important it is in controlling gene expression. Medical people declared the appendix a vestigial or useless organ and cut it out, although recent research has demonstrated that it serves as a reservoir for bacteria essential to digestion. Shrimpers call all the marine species in their nets that aren’t worth money “trash.”

For years little colorful hard-shelled rock shrimp were pushed through the scuppers along with the rest of the bycatch. There was no market for them, even though the shrimpers often took them home to “cook up a mess to eat.”

Shortly after I (Jack) returned from Madagascar and started a marine specimen collecting service in Panacea, I was back on shrimp trawlers in Apalachicola, gleaning through their catches and picking out octopuses, sea horses, and a plethora of other sea creatures.

When white shrimp season ended in November, most fishermen left their boats docked for the winter, waiting for the hoppers to run in April. Dave Silva was one of the few captains who went looking for hoppers in deep water during the winter, and he wasn’t afraid to risk his nets dragging in rough sponge bottoms. I was aboard one trip, when he hauled his nets from 70 feet of water and buried the deck in a beautiful little hard-shelled shrimp I had never seen before. He called them “rock shrimp” because of their rock-hard shells. They were gorgeous creatures, purplish brown in color, with white stripes on their legs.

“Take some of the rock shrimp home and boil them up,” Dave said. “They’re real good. We can’t sell them; there’s no market for them.” Neither was there a market for the strange-looking bulldozer lobsters that flipped and crawled slowly around on the deck like their namesake. The rock shrimp were fantastic, with an unbelievable taste that was more like New England lobster than shrimp. And the bulldozer, or slipper lobster, was just as good as, if not better than, the spiny lobsters that were caught in the Keys. Dollar signs danced in my eyes (see Figure 7.1).

Courtesy of the Florida Department of Agriculture

We started marketing rock shrimp to fancy seafood restaurants, fish markets, and grocery stores. I printed brochures and hired a friend to peddle them door to door in high-end neighborhoods. Gourmets loved the taste but complained that the shells wore out their fingers trying to peel them. Furthermore, the gut was filled with sand and grit, since rock shrimp love to eat tiny mollusks and worms that live on the coarse shelly bottoms. So sales were slow at first.

Hoping to find a big sale, I took samples to the old Fulton Fish Market in New York. What a place! Before the new sanitized one was built, there were stalls of every imaginable seafood. At four o’clock on a cold winter morning, rough-looking men wearing boots dragged titanic flounders and eight-foot-long headless swordfish across slimy snow-covered sidewalks with boat hooks. Amid the noise and bustle, peddlers hawked their product in a feeding frenzy of restaurant buyers bidding and arguing over the price. There was no end to the seafood that was brought in. Trucks were lined up everywhere, their engines rumbling as teamsters unloaded them. Men warmed their hands over a fire that burned in a metal drum beneath the subway overpass and then unloaded hampers of bubbling live blue crabs from Virginia. Some stalls specialized in mussels, oysters, clams, and cans of shucked scallops. One truck from Maine unloaded hampers of green sea urchins with their spines still moving, and bags of live lobsters. Another bore big black cod from Canada—before the fishery collapsed. There were striped bass from Long Island; whiting and grey and speckled trout from the Carolinas; grouper, snapper, and sharks from the Gulf of Mexico. Big red scorpion fish lay gleaming on beds of ice, their eyes glazed under the lights, all fascinating to my eye. I went from stall to stall showing my rock shrimp. No one wanted them. “Look, man, I sell fish and shrimp. I’m not a missionary. I can’t sell these,” one vendor said sympathetically but firmly.

Then I came to a stall where buyers were lined up filling bags of big white shrimp from Florida. To my surprise, there was an unsold bin of headless rock shrimp. The vendor shrugged, “No one wants them; no one knows what they are. I haven’t sold any!” They came from Rodney Thompson, who built the first fiberglass 73-foot shrimp trawler in the Western Hemisphere and then almost went broke trying to shrimp it. “One lonely afternoon, we tied up at Port Canaveral next to the NOAA Research Vessel Oregon II,” he later wrote. “Captain Barret looked at our empty nets and grinned, ‘Do you want to make a million dollars? I’ll show you how!’

“We were hesitant, but we were starving. The next day, in the wake of the Oregon II, we found ourselves 20 miles east of Melbourne, Florida. We dropped our nets and after an hour decked over one thousand pounds of ‘peanuts’ or ‘hard heads.’ The captain of the research vessel (who also helped develop the royal red shrimp fishery) said, ‘If you can figure out how to sell those ‘peanuts,’ you’ll be a millionaire.’”

After heading the rock shrimp, Thompson shipped them to fish markets throughout the country. He ran into the same problems trying to sell them until he designed a machine with a high speed spinning blade that split the shells open. The shrimp could then be broiled like lobsters. He sold his boat building business and started the Dixie Crossroads Seafood Restaurant, in Titusville, Florida, specializing in rock shrimp, and he indeed made his millions.

Broiled in their shells like a lobster, they quickly became a popular seafood delicacy. We, on the other hand, nearly went broke. While we were pioneering the market on Florida’s west coast, the fish house owners, who controlled the fleet, watched and waited until the market took off. Then all our customers were suddenly buying direct at a lower price. We were stuck with three thousand pounds of rock shrimp in the freezer. A dealer took them off our hands with a check that bounced. The day we finally broke even, we had a great celebration and vowed to get out of the seafood business once and for all.

Various seafood processors tried to get into the market by using the Laitram shrimp-peeling machines. They peeled and deveined white, pink, and brown shrimp using a series of oscillating sandpaper-covered rollers that scraped, pinched, and jiggled the shells off the meat and washed away the vein. This ingenious machine was invented by a sixteen-year-old boy, J. M. Lapeyre, in Louisiana in 1943 when he stepped on a well-aged shrimp at his father’s shrimp processing plant and it squirted cleanly out of its shell. Inspiration struck, and he ran some shrimp through his mother’s wringer washing machine. At first, the slime gummed up the rollers, but when he added water, he started popping out shelled shrimp. What his mother thought of the experiment was not recorded, but the family soon founded Laitram Machinery. It revolutionized the shrimp processing industry, with shelling machines producing a thousand pounds an hour and doing the work of thirty to a hundred fifty people peeling shrimp by hand.

But the machines fared badly with the tough shells of rock shrimp, so Rodney Thompson kept his rock shrimp market. For the next ten years his fleet of rock shrimp boats produced about ten million pounds of processed shrimp a year, employing dozens of women who worked his splitting machines and cleaned them by hand.

In the 1980s, the Pascagoula Ice Company successfully modified its Laitram machines, mechanically mass-processed the rock shrimp, and turned the crusty hard-shelled rock shrimp into tasty bites of lobster meat. The gold rush was on as other processing companies followed suit and the rock shrimp beds in the eastern Gulf and the east coast of Florida were under full attack from boats from Mississippi. Dozens of trawlers arrived on Florida’s east coast, some of them 110 feet long, dragging as many as four 60-foot flat nets at one time. They could catch and hold more than five thousand pounds of rock shrimp a day in their freezers. Catches peaked in 1991, when 40 million pounds of rock shrimp crossed the docks in Florida, and then catches rapidly declined.

Along with royal reds, these deeper cold-water shrimp reproduce more slowly than warm-water shallow pink, brown, and white shrimp. The little hard-shell shrimp live almost twice as long as their softer-shelled cousins, produce fewer eggs, and grow slower, making them more vulnerable to overfishing. Desperate to maintain their cash flow and make their huge boat mortgage payments, the super-trawlers moved ever deeper into the rock shrimp spawning grounds further south. They caused enormous damage to fragile deep-water Oculina coral reefs that grow in bizarre spires called “cones” or “steeples” because they look like church steeples. The east coast of Florida is the only place in the world where these unique structures grow, providing a haven for marine life and structure for spawning rock shrimp. Using modern bottom plotters and GPS, the trawlers could safely crisscross the sides of the steeples without hanging up their nets. But the heavy chains and doors devastated the seafloor, much like the trawlers did off Apalachicola when they stripped the sponge bottoms. Inevitably, a few years later the fishery collapsed. There weren’t enough shrimp left to pay the costs of a fishing trip.

Today the Oculina reefs are off limits; the number of boats permitted to fish is strictly controlled and landings have stabilized. Since marine bottoms are in the public domain and marine life is a public resource, government regulators control fishery harvests. They now require shrimpers and other fishermen to use an electronic vessel monitoring system that puts out a signal when they’re approaching the Oculina banks or other closed areas. The signal is uploaded to a satellite, which is tracked by NOAA Fisheries technicians. It warns the boats that they are approaching a closed area. If the fishing boat continues, the Coast Guard is notified and dispatched.

Across a continent from the Florida rock shrimp grounds, we stepped aboard Bruce Gillespie’s 26-foot-long Commander sports vessel to head out on a prawning expedition from Courtney, British Columbia. Unlike the boom-and-bust rock shrimp experience, a more sustainable fishery developed in the Pacific Northwest for seven species of the cold-water shrimp and prawns in the family Pandalidae.

After days of gloomy, cold wet rain, the rising sun was indeed a warm sight. For a few moments, the inland sea was pearly white with the early morning light. Seagulls flew across the skies or perched on the water, waiting for fish to come up. We watched the sun rising over the mountains, bathing the shoreline in light, bringing out the fall colors of festive and bright yellow leaves, and chartreuse green. The scenery dominated in this place of commercial and sports fishing, where aquaculturists grew clams and oysters in rafts, sea lions climbed on them to sun in the afternoon, and First Nation (Native American) fishermen set their gill nets to catch chum salmon. We were after spot prawn (Pandalus platyceros), which is the largest of the pandalid, or northern pink shrimp. Its geographic range extends from Southern California up to Alaska’s Aleutian Islands and around to the Sea of Japan. The spot prawn fishery began in California back in the 1930s, when Monterey fishermen started landing spot prawns from their octopus traps. In the 1970s, it spread up and down the Pacific Coast from California to Alaska.

“We’re a month early,” said Bruce. “Most people around here don’t start prawning until November or December. They want those Christmas prawns to put in their freezer, and that’s when they start. The salmon are running now, or the guys are in the woods deer hunting. Later on, when the prawns are bigger, and running, there will be forty or fifty floats out here, and you have to watch out that they don’t get tangled with yours. Then the commercial season starts in February.” Commercial shrimpers can fish two hundred fifty traps and can fish from sunset to sunrise during the two-month season that begins in February. They load down with prawn in a short, vigorous, and highly profitable season. About five million pounds are landed each year. The recreational fishery is subject to daily catch limits, but the commercial fishermen have none.

It was a short thirty-minute ride over flat calm water before we arrived at the prawning grounds. Over the years while working on scientific collecting expeditions or on writing assignments, we had shrimped in South America, Africa, Malaysia, and China with flat coastal landscapes and marshy muddy rivers that turned into a faceless horizon of rolling seas and whitecaps. Here it was calm, deep, and protected. Somewhere, fifty miles or so away, across mountains and forested landscape, this sound connected to the Pacific Ocean. But as we set out in Bruce’s little boat, it was hard to think of it as anything but a mountain lake. Long ago, a glacier gouged out the land, and the sea flooded in. As Bruce unstowed his prawn traps to get ready for the day’s fishing, the sea, if it could be called a sea, was calm, with barely a ripple on the surface. But it reached to depths of 200 feet or more of freezing water—too deep to span with bridges. So ferries ran back and forth to the opposite shore.

Everything on this charter recreational boat was organized and neat, from the dozens of diverse fishing lures in a rack on the cabin walls to the fishing rods that were held in place inside the gunnels. Most of Bruce and Nancy’s clientele were after salmon, trout, and other large fish, not prawns. The few who saw his ad on the Internet and went prawning did so more to see the scenery and be on the water.

We carried aquariums, cameras, tape recorders, notebooks, and Greg Jensen’s book, Pacific Coast Crabs and Shrimps. A professor at the University of Washington, Jensen spent a lifetime studying the crustaceans of the Pacific Northwest. “One doesn’t shrimp in Canada,” Greg corrected us. “One goes prawning. In most places the names are interchangeable.” Here in the Pacific Northwest they prawned with traps, and at the height of the season the sea was polka-dotted with their floats.

Most of the prawn industry centered on the smaller Pandalus eos, which are caught in great numbers by commercial trawlers dragging nets over the bottom. Pacific prawns live in the cold depths, where the water temperature hovers around 40 degrees year-round. If you fell overboard, you wouldn’t stay alive much more than fifteen minutes, but the shrimp and a whole cadre of fish and Dungeness crabs like it down there. They differ from southern pink, brown, and white shrimp in that they have a large carapace and a relatively small tail, but because they are shrimp, they taste good.

Most recreational fishermen simply broadcast their traps and hope for the best, but after fourteen years of fishing the same waters, Bruce knew the bottom contours, submarine gravel beds, and rocks intimately. He carried eight plastic-coated wire traps that he had designed and made himself. As recreational fishermen, we were allowed two per person. Some of his traps were so close to shore that, as the tide dropped, exposing flats along the shore, we could see the rocks and brown clumps of seaweed hanging limply. If this were the shallow bays of Florida, we’d be running around, but here we were looking for a different shrimp in a different world.

Bruce unpacked the frozen plastic drink bottles filled with bait. They were riddled with holes so that the juices could flow out. His bait was secret, but he admitted to using a blend of commercially available aquaculture “starting” pellets. Some of it was fish meal, mixed with brown fishy-smelling salmon chow from the salmon farms. “The shrimp love it,” he said.

Nancy ran the boat while Bruce studied the fathometer, looking for just the right spot to place his traps. Down in the cabin, he showed us the depth recorder. “You see how it drops off on the south end of the line,” he said. “The bottoms are different, and so are the shrimp, in just a short distance. If you put traps at random, you catch a few, but not in volume. I know from the sound what’s on the bottom; you don’t see it on the charts.” He checked the contours and the depth of the water and watched the shore for landmarks.

Spot prawns tend to inhabit rocky or hard bottoms, glass-sponge reefs, coral beds, and the edges of marine canyons. Perhaps they find food there, or larval transport carries them to a particular spot, but there they stay. Their distribution is notoriously patchy, and no one knows why.

As we approached the spot where he planned to set the traps, Bruce hopped back and forth, up and down the steps leading into the small cabin, studying the fathometer, looking for the right spot that lay below the transparent blue water, out of sight.

“Neutral,” he called out, and Nancy pulled the gear shift lever back so that he could lower the trap into the water. Typical of all the shrimp cages used along the Pacific Northwest, all the trap openings pointed upward. “We make it easy for them. The shrimp crawl all around the outside of the trap, trying to get to the bait, then go up the shoot and fall off into the cage.” People had tried these traps in the Gulf of Mexico and South Atlantic for catching penaeid shrimp, but they never really worked out.

Down into the blue water went the two baited wire cages, the rope uncoiling from the milk carton. Finally the big red inflatable float was tossed overboard with a splash. Fifty feet from where the rope was tied onto the trap was a four-pound weight, which acted as a shock absorber. “Wind will make the trap move,” Bruce said, “when it pushes against these buoys. The shrimp won’t go in, but this lead weight keeps the traps from moving on the bottom.” The inflated red buoy bobbed on the blue sea behind us as he headed for the next set. The first two traps settled to the exact spot where he wanted them to be, next to the rocks, where, according to the graph on the fish finder, the bottom rose. After the last of the traps were deployed, our guide cut the motor and we drifted, waiting for the hour and a half until it was time for the traps to be pulled. There was no leaving the traps in the water overnight.

“We can only leave them soak for an hour or two,” Bruce explained, “because predators, like giant sun stars, octopuses, and other fish will get in and eat the shrimp.”

Deep-sea rattails, six-gilled sharks, rock fish, and giant cold-water octopuses lived in the glacially carved submarine terrain. Salmon, sea lions, and a plethora of other marine life made their way in from the fifty-mile-distant sea, or grew up in the deep waters. When schools of herring came in to spawn, the water became cloudy with milt. Steelhead salmon ate the herring and gulped down schools of anchovies in a fish-eat-fish world. While we were waiting for the traps to come up, Nancy brought out chunks of smoked salmon, which they had caught and prepared themselves. “We catch five or six salmon a year, and that’s enough to live on,” she said, “but a lot of these sportsmen are greedy and catch their limit of two a day. The fish are huge; there’s no sense in doing that.”

Killing time, we set off exploring, leaving our big red buoys sitting quietly on the surface of this millpond of a sea. We passed rafts of floating logs with more than a hundred barking and croaking sea lions lounging about in the sunshine that was so rare on Vancouver Island’s cloudy rainy coast. They complained loudly as we encroached on their comfort zone, many flippering and heaving their way into the water with a splash and swimming around with their heads up. Some were on their backs with their flippers in the air.

“They’re so abundant they’re a nuisance,” Nancy said. “They eat tons and tons of fish. They go upriver and gorge themselves on coho salmon. Anything they can get their jaws around, they eat.”

When it was time to pull the traps, Bruce caught the buoy with the boat hook and ran the line through his homemade puller. It was smaller than commercial models, designed to fit his boat and give lots of room. He was embarrassed when the trap came up empty. “I must have had this one off the edge. We’re fishing on a small patch of gravel bottoms,” he explained, “and if we get off, we don’t catch them. The traps are a hundred feet apart; we’ll do better on the next one.”

He was right. Minutes later, the next trap, attached to that same line on the buoy, emerged from the 200-foot depth full of shrimp. Inside the wire, we could see pinkish-orange jumping prawns, thrashing and kicking inside the trap. There was also a big yellow multilegged creature, a sun star, hanging on the surface. “We don’t want him,” Bruce said. “They’re nasty. The sun stars come in here to eat the shrimp. Sometimes we find them inside the trap, and there’ll be nothing but shrimp skeletons if you leave them too long.”

He opened the trap lid and shook five or six pounds of jumping and flopping red shrimp onto the culling table. We counted seventy-five spot prawns and one coon-striped shrimp. The shrimp were a dazzle of red and pink, with delicate candy-cane-striped legs. Their bodies had an almost luminescent translucence. Looking at the lack of bycatch, we had to agree with the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s assessment that the northern pink shrimp trap fishery is one of the least damaging and most sustainable.

We had handled hundreds of shrimp of many species. We knew the spikes of pink shrimp, browns, and whites, the sea bobs, and the broken-backs. Out in the Gulf of Mexico, nearly two hundred miles from shore, we had caught deep-sea royal red shrimp off the decks of a 90-foot steel hull, working in blue water. We handled rock shrimp with hard shells, and big fresh-water prawns from the rivers in Costa Rica. But nothing was as evil-looking as the rostrums or head spines of these cold-water pandalid shrimp that projected from their heads. Needle-sharp swords, they were wickedly curved, like the knives of Gurkha soldiers. Looking at them we understood why early biologists named this spine after the battering rams mounted on the prow of ancient Roman war ships. Of the seven species of Pandalus in the area, species that have shorter rostrums generally live under cover, beneath rocks or logs, while those with long rostrums live out in open waters. According to Greg Jensen, the rostrum makes them hard to swallow, and they also use it defensively. When a fish grabs a shrimp, the shrimp goes limp while the fish tries to swallow it headfirst. But with that spiky rostrum and antennal scales, the fish releases the shrimp for a second, trying to get another bite, whereupon the shrimp has a chance to jump away and escape (see Figure 7.2).

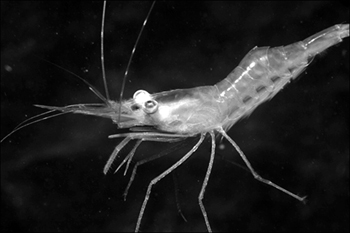

Figure 7.2 Northern pink shrimp

Courtesy of Greg Jensen

Looking at these daggers and remembering stories of people who were stuck by them and got infected, we gingerly placed the shrimp in the glass tank, trying not to get stuck. It was hard to tell the species, as they all looked alike. Only a specialist could tell the difference. The prawn’s legs were like candy cane stripes, while the coon-striped shrimp had white spots on their abdomens. A few soft-shell shrimp were in the catch, which meant we wouldn’t have to shell them before eating them. When a prawn or shrimp gets ready to molt, it grabs onto a rock, and in thirty seconds it rolls out of its shell. The empty shell looks like cellophane.

Like many other caridean shrimp species, these had a confusing sex life. The spot prawn is called a protandric hermaphrodite, which means that it starts as a male and then becomes a female. It generally reaches sexual maturity as a male by its third year. After it mates as a male, it enters a transition phase and in the fourth year changes into a female and then mates as a female. When the fishermen go after the larger shrimp, they catch out the reproductive females (see Figure 7.3).

Courtesy of Greg Jensen

Nancy was on deck, scrutinizing the catch for the big female prawns to throw back. She looked for the pinkish-orange mass of eggs beneath their carapace. “The eggs are just starting to show, and they haven’t really fluffed out,” she said. She tossed them back as Bruce moved the boat back over to the gravel patch of bottom 200 feet below to pick up the next float. Watching them tail-flip their way back down into the sea, we wondered about their chances of getting to the bottom alive. “I don’t know. I think most of them make it,” Nancy said. “Not many fish feed on them up here on the surface. You don’t ever find them in salmon, but the rock fish on the bottom love them.”

“Sometimes we get big octopuses in the traps,” she said. “I don’t know how they squeeze into the openings, but they do. Then you really see the shrimp shells pile up. They eat them as fast as they can catch them.”

Aboard the little sports boat, Bruce broke the heads off the shrimp that didn’t have eggs. We had them for lunch. The meat was a firm dazzling white—whiter than the whitest shrimp I ever saw in the South Atlantic. But finding them in the market is rare, since the biggest prawns are quick-frozen at sea and exported to Asia. Preparing them properly and aesthetically arranging them in the packaging is an art form. Down the bay, five or six First Nation gill netters were catching salmon. Although Native art depicts salmon, killer whales, and birds along the Pacific Northwest, there’s not a single totem pole of a shrimp, or a shrimp effigy. Just as on the Gulf Coast and South Atlantic, shrimping is a recent fishery.

As the afternoon sun was starting to set, we headed back to the dock, over the clear glassy deep water. Down below were shrimp—shrimp of another color, shrimp of another species—another shrimp in another world.