To Do or Not to Do

Icebergs of hindsight

Decisions, decisions, decisions! Everywhere you look there's a decision to be made. Faced with an ever expanding list of choices modern day brains are forever having to make them, some large, some small, some easy and some not.

Most decisions are made without you even realizing; with most of the action taking place deep down in your subconscious. Your conscious thinking on any given matter has an estimated capacity of 40 bits whilst the subconscious processing capacity is estimated at 11 million bits of information. In other words, the tip of your decision-making iceberg – the conscious part – is tiny in comparison to the immense bulk of information that is effortlessly crunched beneath the surface of your awareness.

The first you get to know about what's going on deep in the decision-making circuits of your brain is usually when, after much sub-surface deliberation, a conclusion has already been reached.

As a rational person, it really does feel like you are carefully considering your options, but there is ample evidence to suggest that this feeling is misleading. Most of the explanations you might give for why you made a certain choice are usually retrospective, the decision having already been made before you've even consciously mulled over the pros and cons.

Most of the time when you think you are making a logical, well thought out decision, you are really just attaching a feasible sounding explanation to a decision that you have already made on a purely emotional basis. So, in reality, instead of thinking something through, more often than not, you are unwittingly looking back in hindsight at a decision that your brain has already put to bed.

Got a hunch?

With icebergs of hindsight in mind, and taking into account the huge influence of your well-developed perceptions, what you might regard as being “gut feel” decisions are in fact the result of an awful lot of behind-the-scenes hard work by your 24/7 brain. Thanks to its uncanny ability to learn from past experience, it's hardly surprising that when you trust your instincts, you are often proved to be right!

Circumstances in which your gut feelings guide you best usually occur in situations where you have amassed extensive experience. If, for example, you have accumulated hundreds of hours of experience on the paintball battleground, your instincts will have become honed to know exactly when and where it would be unwise to suddenly stand up or go poking your head through an inviting gap, no matter how strong the temptation.

The instinctive feelings we experience in the pit of our stomachs when we make certain important decisions are, in fact, visceral sensations directly related to subtle emotional memories of the outcomes of past similar choices.

Instinct may at times feel literally like a “gut feeling.” This results from blood vessels of the small intestine contracting to make more blood available for a busy brain. Your digestive system becomes a low priority when the brain is excited by or worried about an important decision. At these critical moments blood is diverted to your brain to meet its increased demand for oxygen and glucose. In other words the “gut feeling” that you can sometimes feel relates in part to the physical sensations produced when blood is siphoned away from your stomach to fuel your brain.

Reward Line

Human brain imaging has confirmed that a specific brain network swings into action when we feel pleasure – the Reward Line. As decision making involves evaluating the potential reward value of of each choice in the light of past experience, your “pleasure pathways” or Reward Line is vital to any decision.

The VTA stop (Ventral Tegmental Area) is at the very heart of your pleasure network. It resides in your midbrain, an ancient part of your brain sandwiched between your spinal cord – sending electrical signals in bundles of brain wires to and from your body, and your Thalamus. This is the main biological junction box through which these neural brain wires connect with the Cortex (the folded outer surface of the brain), where most sensory and cognitive processing takes place.

Quenching thirst, eating when hungry and sexual interactions all induce responses in your VTA, not only making you feel good in the moment, but also encouraging you to repeat the same behaviours in the future in the hope of re-experiencing the same pleasurable sensations.

The pleasure derived from receiving gifts, admiring a beautiful picture, listening to music or sharing a joke all stems from activation of your VTA. This in turn stimulates other parts of your Reward Line, like the Nucleus Accumbens stop, which is critical to the decision-making process as it's fundamental to our ability to anticipate future pleasures.

What do you fancy for dinner?

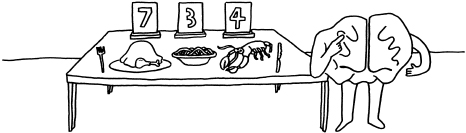

There are five basic steps that your brain must go through during any decision-making process. Let's imagine, without taking into account any special dietary requirements you may have, that a friend gives you a call to invite you round for dinner and offers a choice of three dishes.

Step 1. You picture in your mind's eye all the options – in this case the choice is between a pasta, chicken or seafood dish.

Step 2. Your brain attaches a value to each option, a neural mark out of ten, if you like. Of course you are not consciously aware of how the exact details of this scoring system are worked out by your brain. The numbers are arrived at almost entirely at a subconscious level based on activation of the Nucleus Accumbens or “Buy Button.” Neuroscientists hate this label because it is an oversimplification – but it is easier to say, and remember!

Decision making relies heavily on previous experience of the available options and the neural score that each alternative achieves is weighted heavily according to how much pleasure was derived from those dishes in the past. This acts as a prediction of how rewarding the option might be in the future.

Based on collective experiences, and to a large extent your most recent experiences, your brain attempts to predict how much joy is likely to accompany each option and settles on scores of 8, 7 and 4, respectively.

Let's imagine that, under normal circumstances, the seafood would have scored a predicted value of 9 rather than the 4 it got today, as it is your favourite food. However, a recent unpleasant seafood encounter has left you reluctant to go for this option and so your estimation of how enjoyable it would be has been drastically reduced, at least for the time being. Were you to be offered the same dish in a year's time, with the memory of the seafood disaster long behind you, it may well be marked back up again in the future.

Moments before you state your preference, you recall that you already had pasta for lunch; you don't really fancy it twice in the same day, so today its predicted value gets downgraded from an activity level of 8 to a 3. This leaves you with the chicken option topping the table with a sturdy 7. Despite being a bit boring (it's your default choice) at the end of the day you know you like it; it's a safe bet. Hence, the final values attached to the three choices end up: Chicken 7, Pasta 3, Seafood 4.

Step 3. Your brain simply compares these reward predictions. Again this occurs mostly just beneath the surface of your awareness, with the highest scoring option being the one you “fancy” for dinner. In this case your “gut feeling” would inform you that you'd like your friend to cook you up a tasty chicken meal.

Steps 4 and 5 are both made post selection and are vital to ensure that the decision-making process improves to serve you better in the future.

Step 4. This involves evaluating the outcome in light of the original prediction – was the chicken the best option after all? Or in retrospect would one of the other options have been better?

We've all experienced food envy in a restaurant where other people's choices look much more appealing than our own.

It is at this point that Step 5 takes place whereby, having evaluated the outcome, we update the decision-making process for future reference. An error message is sent to brain areas involved in Steps 1–3 to ensure that a better decision is reached next time round. For example, this may involve updating the predictions for this option in light of the fact that your friend's homemade “southern fried” chicken dish is rarely as tasty as the take-away version that you have become so accustomed to. Or, perhaps, if the meal was a spectacular success, the positive associations with this option would cause the likely reward value to be updated so that chicken moves up the scoreboard.

As our experience accumulates, we are, by the time we reach adulthood, all experts when it comes to everyday decisions like selecting what we want for lunch. Thanks to vast amounts of experience in getting this decision right or wrong we don't need to invest too much brain power to achieve our goal of biting into something that we know is very likely to satisfy. Consequently, we are usually pretty good at predicting which option will yield the greatest gastronomic enjoyment and can thankfully make such decisions on autopilot.

However, in many circumstances, we don't get to see the outcome of our decision until long after we've made our choice. Take for example choosing a holiday. The time lag between choosing a destination and actually getting to experience it, can often be several months. In these circumstances it can be very difficult to remember what you were thinking at the time you made the decision, which makes updating your decision-making process for next time round very tricky indeed.

This situation is highly problematic to anyone who wants to stop making the same mistakes over and over again. Under these circumstances most people rarely learn from their mistakes. One of the keys to many high-achieving people being so successful is that at the time of making a decision, they make notes on the main influencing factors behind their thinking. Once they know the outcome, if it's not the one they expected, they revisit their notes to get to the bottom of why things haven't turned out as intended. Despite the discomfort of going back, scrutinizing, being honest and facing up to their errors, they recognize it as an absolute must when it comes to staying ahead of the game.

The reality is that most of history's super successful individuals have all made a lot more mistakes than others – only because in comparison, they have had far more attempts at trying out new things. But what really sets them apart is that having taken on board lessons learnt from these past mistakes, they keep their decision-making systems bang up to date.

“Failure is simply an opportunity to begin again, this time more intelligently.”

Henry Ford

Emotion-flavoured decisions

Even with note taking, explicit memories of many individual decisions will have long ago faded from our conscious recollection, and in many cases will have completely disappeared. Forgotten they may be, but the feelings associated with the outcomes are still with us, safely logged away deep in the memory banks of our brains. They consist of a summary of the emotions that those individual experiences gave us – with the most poignant and the most recent examples being at the very top of the pile.

If we really wanted to understand why our brain is urging us to make one choice over another we may, in many instances, have to work back until we arrive at a poignant experience that happened long ago. At the time it may not have seemed like an experience of any note but it gave birth to a deep-rooted belief. A belief that always generates the exact same emotional bias whenever we think of it.

Push and pull

When it comes to emotional bias, our more difficult choices are often finely balanced. We are drawn by a very subtle emotional pull towards similar options that have in the past resulted in positive outcomes and a gentle emotional push away from those that resulted in a negative one.

We've already heard that the pull appears to be generated in the Buy Button (Nucleus Accumbens stop). The push can be caused by several different factors, including the discomfort associated with a hefty price tag. This one is created in an island of brain tissue known as the Insula – a stop on the Limbic Line buried deep between your Temporal and Frontal Lobes. Another form of push instinct sets warning bells ringing in your Amygdala (also on your Limbic Line) when you worry that a choice is simply too risky.

Overall this system of push and pull has served us surprising well over many years. It's clumsy in certain circumstances but overall highly effective when it comes to staying alive! Even in this day and age when survival is relatively straightforward, it operates perfectly adequately in most decision-making scenarios.

Our instincts can be trusted even when making highly complex decisions. When there is an overwhelming amount of information to consider, following our instincts can lead to good decisions, but only if we first invest the time to gather together and unhurriedly consider all the relevant facts. The secret is to postpone the final decision for a short while, to sleep on it for a couple of nights – giving your subconscious a chance to stir the pot – and only making the decision based on gut feel once it's had a chance to assimilate and make sense of everything.

Danger zone – excessive buy button activity likely

Anything that makes us feel excited drastically increases activity on the Reward Line, bringing us closer to “going for it” – whatever it happens to be.

Danger zones are entered when activity on the Reward Line is seriously ramped up by exciting sensations, for instance those generated in a lively bar. Loud music, flashing lights and attractive bar staff, all help to drive up sales by throwing our Reward Line into a frenzy – making us more likely to spend far more than we ever intended.

In such circumstances the desire for instant gratification will prove almost irresistible, and any long-term plans of saving for a new car or summer holiday will go straight out the window.

“The chief cause of failure and unhappiness is trading what you want most for what you want right now.”

Zig Ziglar

The same fate has befallen many a determined plan to lose weight. When in a restaurant, having stimulated the Reward Line with good food, a few drinks and pleasant company, diets go out the window. We eat 25% more food when dining with one other person, 39% more when dining as a threesome and a whopping 79% more when eating with three others! All it takes is just one person to ask for the dessert menu and its goodbye healthy eating regime.

Losses loom larger than gains

Brain scanning experiments have revealed that our favourite part of the decision-making apparatus – the Nucleus Accumbens (NA) – not only increases when the gain a person anticipates is exceeded, but also decreases when the expected gain doesn't happen. Worse still, if they suffer an unexpected loss the activity level decreases even more. The most important thing to take into account about the NA is that an unexpected loss results in much larger reductions in activity than the increases in activity that occur when there are gains of exactly the same size. Your Reward Line overreacts disproportionately to losses in comparison to gains

This feature helps to explain why we humans are, on the whole, so extraordinarily loss averse. Most people won't accept a gamble unless the potential gain is at least twice the size of a potential loss. Hence the minimum return in a casino is double or nothing.

Happily the reverse is also true – your NA is hyper-responsive to unexpected gains but this time in the positive direction – so you can use this “Power of Surprise Rewards” to your advantage. If you give someone a present in circumstances where the recipient has a fair idea what the gift is likely to be and when they are likely to receive it – like receiving yet another bunch of wilting flowers from the local garage on Valentine's Day – only a small increase in activity will be triggered in the reward pathways. This corresponds to the recipient feeling “quite” happy, but hardly overwhelmed. Not great, but far better than a fully expectant person not receiving anything at all – which would result in a rapid deactivation of the reward pathways and a corresponding crushing sense of disappointment.

If, however, there is an element of surprise in the gift-giving scenario then that exact same gift can induce a completely different response in the recipient's mind. If flowers are received completely out of the blue then there will be a disproportionately large response in the reward pathways and a commensurate surge in happiness; usually resulting in a rather large haul of brownie points!

The main thing to remember is that the Reward Line creates a model of what is likely to happen on any given day, in any given environment, and these expectations are always adjusted and updated according to experience. The more an experience deviates from expectation, the greater the response in the reward pathways and the greater the emotional impact of that experience.

The price of impatience

If you were offered the choice of being given £100 today or £110 this time next week, which would you go for? Many studies have shown that the vast majority of us would choose to take the £100. Our love of instant rewards and our fear of uncertainty have proven to motivate people to accept less value in return for immediate reward. And why not?! We all know that a lot can change in a week, the offer may be withdrawn, the person making the offer might keel over, or it might be us – the expectant recipient – who is no longer around tomorrow. Who knows what's around the corner! The problem with this tendency is that many of life's most important decisions, like saving enough for retirement, require immediate gratification to be snubbed in favour of much more important long-term goals.

Experience really does count

Our instincts are right in many circumstances, but they can also be very misleading. Subconscious brain processes furiously working away beneath our awareness will do all the hard work of sorting all the relevant information for us, but they will only do a good job if we have extensive experience of similar situations. If we've never made a certain type of decision before, our intuitions will likely lead us astray – we'll always have a hunch one way or another even in situations that we have little understanding of. Our instincts can only guide us well once our subconscious has something concrete to work with and the more experience, the better the job it will do.

Buying more time – to investigate further in an emotionally neutral state of mind – is vital to making better decisions, especially when you are in emotionally-charged danger zone situations. Sometimes we need to take time to cool down because high levels of both positive or negative emotion usually result in the wrong decision being made. The context in which decisions are made, the brain state you are in at the time of the decision, can fundamentally alter the choices we make. Sometimes we do need to step back, look at things from a different perspective and to see that although the associated risks are worrying, or the long-term goals boring, they are the options that sometimes offer the best returns in the long run. It doesn't always pay to let your heart trump your brain.

Chapter takeaways

- Your brain operates a neural scoreboard of likely outcome predictions based on recent and peak past experiences.

- Logical reasoning often justifies our emotional choice retrospectively. Identify past experiences that might make you feel that way – are they relevant now?

- Trust your instincts in circumstances where you have extensive experience, ensuring you're not in an overexcited state of mind.

- Distrust your “gut feelings” in circumstances where you have little experience or when a certain choice gives you a small quick win over a larger return later.

- Develop your skills of resisting the urge for immediate gratification; it'll pay off in the long run.

- Buy time – but don't postpone forever. Think, research, mull, then go for it!