6

Technology

A Changing Labor Market

The press release touted a most remarkable headline: “Denmark in the world's top 10 for robots.”1

The organization behind the release was not a Danish tech firm, media outlet, or politician. It was Dansk Metal, the union representing blue-collar workers in the Danish metal manufacturing and processing industry. It was clear that the union was proud of this achievement: “An increasing number of employees in the industry work side by side with robots,” the press release read. “Dansk Metal has a target of rounding 10,000 industrial robots in Denmark by 2020.”

I was intrigued by this stance. From visiting other parts of the world, and reading about other times in history, I knew of many more instances where workers opposed new technologies, especially when they threatened to replace their jobs. The most famous case may have been that of the Luddites in England, a group of textile workers in 19th century England who destroyed the new machinery that was disrupting their industry. But throughout the world, including in our time, many others also protested new technologies and the new ways of working they promoted, whether through street protests against ride-hailing firms such as Uber or intellectual protests by politicians2 or academics3 in media.

I too share the concern over the future of work in this era of automation. Back in 2015, I realized we were at the dawn of a new era—one of artificial intelligence, advanced robotics, and integrated cyber-physical systems—and that together they constituted a Fourth Industrial Revolution. The new technologies we were witnessing, including also 3D printing, quantum computing, precision medicine, and others, I came to believe, were on par with that of the First Industrial Revolution—the steam engine—those of the Second Industrial Revolution—the combustion engine and electricity—and that of the Third Industrial Revolution—information technology and computing. They were leading to a disruption of the workforce, changing the nature of not just what we do but who we are, something I previously described in my book The Fourth Industrial Revolution.4

In their landmark 2013 study “The Future of Employment,” Carl Frey and Michael Osborne of Oxford first warned of the kind of disruption this could bring about.5 They notoriously estimated up to half of jobs would be altered in the coming years because of these new technologies, with many of them disappearing altogether. In 2019, Frey followed up on his original study with the equally eye-opening book The Technology Trap,6 showing how today's labor-replacing technologies fit into the longer history of industrial revolutions. It is no wonder then that many people in today's global economy are fearful of what the future may bring and that they prefer instead to hold on to the more familiar world of the past. It explains why political leaders around the world, egged on by voters, are trying to save or revive manufacturing jobs and why they are increasingly retreating into more autarkic ways of running their economy. Technology is an awesome force, in every sense of the word.

But the news from Denmark seemed to suggest that such fears can be overcome and that the newest and best technologies can help workers too, without necessarily replacing them. How was this possible? To find out, I asked a colleague to go to Copenhagen and find out what explained this attitude.

Dansk Metal President Claus Jensen gave us a first convincing argument.7 “Have you ever known of a country or company,” he asked, “that implemented old technology to get rich?” He was convinced that wasn't possible. And he didn't share the doom and gloom vision of some on the future of work: “Maybe Singularity University will think that everyone will be replaced by technology,” he said.8 “Maybe they think everyone will be standing at the sea, looking at robots making everything. But not everyone would say that.” He certainly didn't believe it. It went against his own experience and that of his predecessors at the union in the past 150 years. “Every time we introduced new technology in Denmark in the past,” he said, “we've had more employment.” So to Jensen, it was clear. “We should not be afraid of new technology,” he said. “We should be afraid of old technology.”9

This optimistic perspective wasn't only consistent among the leadership of the union for over a century (the union was founded in 1888, and its first president held the same view as Jensen today), it was also widely shared by the base of the organization—the union members themselves. Robin Løffmann, a 32-year-old ship equipment technician for MAN Energy Solutions in Copenhagen, was one example of that. The son of a car mechanic, Løffmann had the love for cars and engines in his blood. When it was time to choose a profession at age 18, he chose to become an industry technician. Aided by a four-year technical education and a concurrent apprenticeship at a small manufacturer, he easily found a job upon graduating making fuel injection pumps for MAN.

Four years later, in 2012, things could have gone the wrong way for him. His boss told him the company would buy new machinery, which would bring down construction time for the parts from 20 minutes to five or six minutes and drastically reduce the need for human intervention in quality control. Yet Løffmann didn't oppose the new machinery. He loved it. “In other places, they don't want machines to do the heavy lifting,” he told us in an interview for this book.10 “But not so in Denmark,” Løffmann said. Here, “the company will say: can we reskill you to be an operator on a different kind of machines?” In his specific case, Løffmann was sent to Bielefeld, Germany, where the new machinery was made, and asked to “sign off” on the new equipment on behalf of his company. A month later, a specialist of the German company came to Copenhagen and retrained him and three other workers to work with the new machinery.

Løffmann's story is typical for the broader industry. Dansk Metal Chief Economist Thomas Søby told us: “People aren't afraid to lose their jobs, because they have retraining possibilities. We have a very functioning system. When you lose your job, we at the union will send an e-mail or call you within one or two days. We'll have a meeting to talk about your situation, see if you need upskilling, if there are any companies in the area looking for their profile. And we are very successful in placing our members in another job, immediately or after re-skilling. We have established schools all over the country. The curriculum is decided by employers and employees. And they are open to retraining and re-education of the workforce.”11

The constructive and trusting relationship between workers and companies is paying off for Denmark. While the country long ago stopped being the shipyard of the world—that place was taken by mega firms in South Korea, Japan, China, and Turkey—it still produces the engines that keep new and old ships running around the world (the oldest ship engine Løffmann's company maintains dates from 1861; the newest ones are still being made). And the cost advantage it loses in high wages it makes up in the productivity and can-do attitude of its workers. Just before the COVID pandemic hit in early 2020, Denmark had an unemployment rate of 3.7 percent,12 and in the metal union it stood even lower at 2 percent (the fact that the union pays unemployment benefits, and thus has incentives to have as little people unemployed as possible, certainly plays a role). Perhaps more importantly, Denmark's wages are high and relatively equal. A member of the metal union, Søby said, makes about $60,000–70,000 per year, for a maximum 40-hour workweek, while union participation still stands at about 80 percent. Overall, Denmark is also one of the most equal countries in the world in terms of income, though its inequality has been trending upward in recent years.13

This story from Denmark is more remarkable because it contrasts with the narrative in other industrialized nations. The Danes look at it with astonishment. Not too long ago, American, German, French, Spanish, and Italian social security and education systems were on par with those in Scandinavia. But today, Søby told us, he looks with astonishment to what has happened in these countries. While Denmark maintained and updated its social security and education system, others have done much less. The Danish system, he says, works well for both companies and workers. The “pact” between them is that companies can fire workers with relative ease—but that they do pay high wages, contribute to taxes, and participate in reskilling efforts. With salaries taxed at up to 52 percent, there is certainly a price to pay for this “flexicurity” model. But, he said, “In Scandinavian countries, we offer reskilling for fired workers, and are able to place most workers again in a new job. You don't have that [to the same degree] in Germany, Spain, Italy or France.”

The country he is most shocked by is the United States. America dominated the two previous Industrial Revolutions. With its Great Society it was also a place where blue-collar workers could achieve the American Dream. But today, it is no longer a Mecca for workers—at least not from Søby's perspective. Of course, the decline in manufacturing and the rise of the service sector is a global mega-trend, stretching decades and affecting the entire industrialized world. But the pace at which people lost jobs in the US manufacturing sector is extraordinary. Between 1990 and 2016, the Financial Times calculated, some 5.6 million jobs were lost in manufacturing.14 The workforce of entire industrial cities was decimated. Some company towns, cities which all but depended on one industrial employer, were particularly hard-hit. And while many of these jobs didn't disappear altogether but were rather offshored to China or nearshored to Mexico, about half of the jobs did get lost because of advancing automation. At best, low-paid service jobs replaced these well-paid blue-collar jobs. At worst, no new jobs became available at all, at least not for workers without a college degree. Inflation-adjusted wages since 1980 have barely risen in certain sectors. And, despite having very low official unemployment numbers until the pandemic hit, the US labor force participation dropped from an all-time high of over 67 percent in 2000, to around 62 percent in 2020,15 meaning many people stopped looking for work altogether. In Denmark, by contrast, the labor force participation continued to hover around 70 percent even after the pandemic hit in early 2020.16

Why did this happen? “One of the major problems in the American economy,” Søby said, “is a lack of education of the workforce.”17 Unlike in Denmark, there is no widespread system for upskilling workers. It is an issue that becomes obvious in the figures of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).18 Denmark is the OECD country that spends the most per head on so-called “Active Labour Market Policies,” to help unemployed back into the labor market. Comparatively speaking, the US spends a factor of 15 times less. The Danish system is also more inclusive (accessible to a greater percentage of people, regardless of their age, gender, education level, or employment status) and more flexible. And most significantly, the Danish system is the best adapted to labor market needs of all OECD countries, while the US lags behind 19 of the 32 studied countries.

It leads to a chronic mismatch in the American labor market. Even when reskilling is available in the US, economic journalist Heather Long of the Washington Post told us, workers either are often not incentivized to enroll, fearing it won't lead to a job anyway, or they register for some of the most basic IT courses, such as working with Microsoft Word or Outlook. “That's eye-opening to me,” Long said,19 recounting an anecdote.

The problem here, to be clear, is not with the attitude of older workers. It is that when a culture of constant retraining does not exist and workers have not been upskilled once in their career, even a well-funded shock therapy won't suffice. That is also how Thomas Søby sees it, looking at the situation from Denmark: “I understand why workers have something against new technology and robots, because if they were to lose their jobs, they are pretty much doomed. Their skills are very company specific. If you don't have system for re-education or upskilling, you have a very fierce anger. It is very difficult to solve, and they are trying to do it in the wrong way. What you need is better education, and higher unionization.21” In advocating for this type of solution, Søby is not alone. Across the ocean, in Washington, DC, it is also what economists like Joseph Stiglitz propose, or think tanks such as the Economic Policy Institute (EPI, founded by a group of economists including former US Labor Secretary Robert Reich). Josh Bivens, director of research at EPI, made this point in a 2017 study: While in Denmark union participation remains very high, guaranteeing that demands of workers on issues such as pay and training are taken into account, in the US it dropped from about one-third of workers in the 1950s, to about 25 percent in 1980, and barely 10 percent today. That drop in union participation coincided with a rise in economic inequality, and, as EPI argues, with a drop in training programs that keep workers skilled in this age of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and the US workforce productive and competitive.22

In the United States and the United Kingdom, two countries where workers have been hit hardest by the changes in the economic system, advocating for unions and education has become politically polarizing. In the 1980s, conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in the UK and Republican President Ronald Reagan in the US embraced a neoliberal agenda that proved anathema to public investment in fields like education and the power of unions. Under this ideology, collective bargaining by unions was a barrier to establishing free markets, and the state with its taxes and services was a drag on high economic growth. In the US, President Reagan famously fired all air traffic controllers who participated in a union-organized strike, thereby breaking the back of unions in the US. And in the UK, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher broke a major miners’ strike, ending the dominance of unions in her country. Both leaders also significantly lowered top tax rates. This was supposed to free up money for investment by companies and high net worth individuals and realize a trickle-down economy. But it also deprived the state of income to fund public services including education programs. For a long time, it seemed like those kinds of policies indeed helped the economies of the UK and the US. The next years marked a period of high growth in both countries, and by the 1990s, the neoliberal ideology was even adopted by the Democrats and New Labour. But by the Great Recession of 2008–09, it became clear neoliberal policies had had their best years. As we saw in Part I, economic growth remained sluggish in recent years, and wages for many in the US and elsewhere in the industrialized world stopped going up, with many also falling out of the labor market. Today, as the contrasting examples of Denmark and the United States above show, any industrialized country would do well to embrace again more stakeholder-driven solutions and public investment in education. Political color or ideology should play less of a role in this debate than the notion that these solutions simply work.

Singapore is one example of how this works in Asia. In terms of openness to trade, technology, and immigration, the city-state in Southeast Asia is one of the most economically liberal countries in the world. In terms of its social policies, it is a solidly conservative country,23 with LGBTQ rights24 and marriage and human rights more broadly more strictly regulated than in many Western countries. But in terms of its economic policies, its Senior Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam told us,25 the government adopts policies that work, not ones that are ideologically driven. As an island nation that depended for its wealth on its global economic competitiveness, it had almost no choice.

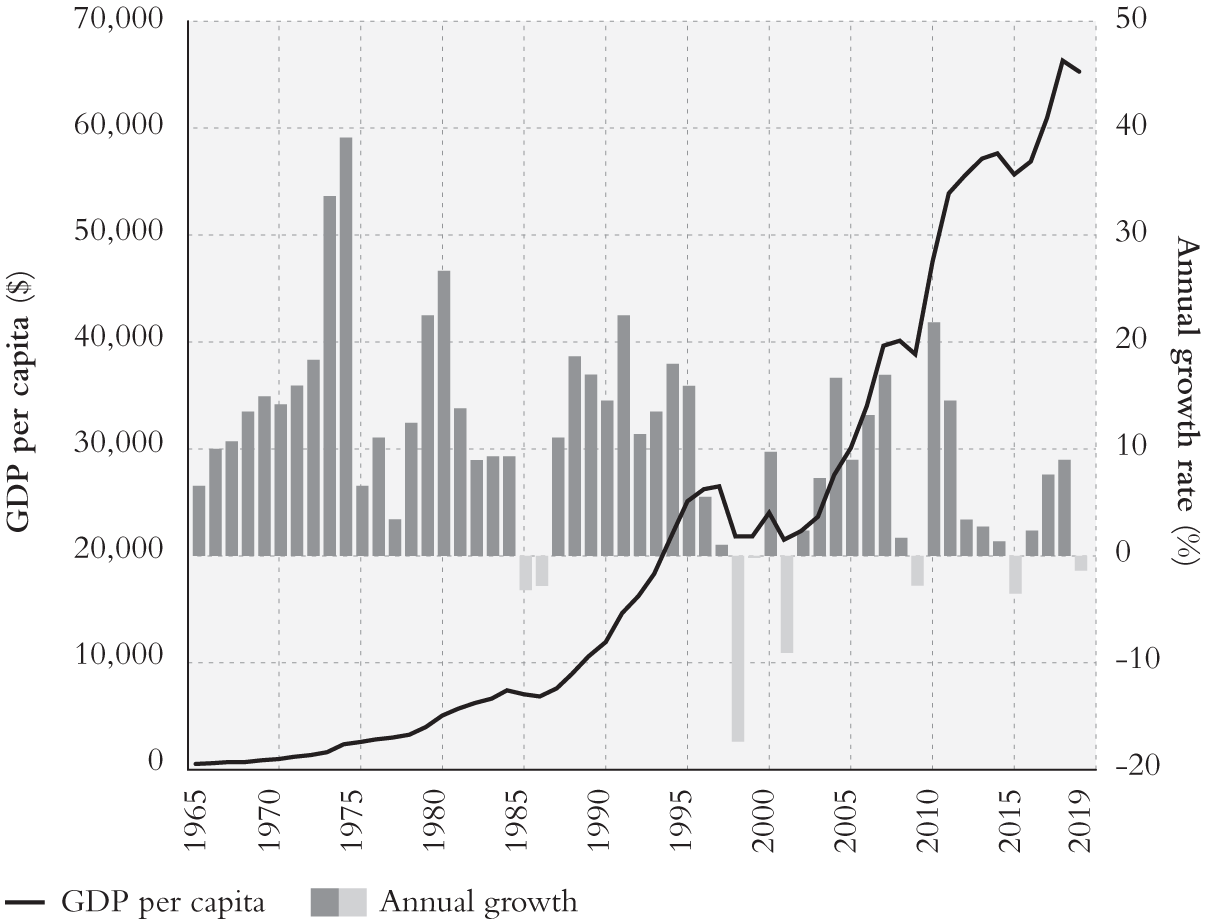

Singapore started its steep economic ascent as one of the Asian Tigers, alongside Hong Kong, South Korea, and Taiwan in the 1960s. In the early stages, the island successfully bet on labor-intensive manufacturing as one of its growth poles. Manufacturing's share of GDP grew from 10 percent in 1960 to 25 percent at the end of the 1970s, in a period where GDP grew by over 6 percent per year.26 The arrival of Japanese and other global companies looking for a cheap manufacturing hub helped many Singaporeans get decent blue-collar jobs and allowed the country to quickly develop: while its GDP per capita was a mere $500 in 1965, it exploded to $13,000 by 199027 (see Figure 6.1).

Figure 6.1 Singapore's GDP per Capita Growth (1965–2019)

Source: World Bank, Macrotrends.

But with newly developing Asian economies like China hot on its heels, Singapore already in the 1980s needed to reskill its workers, in the hopes a more service- and knowledge-oriented economy could help it move up the value chain and make the leap toward a fully developed nation status. For this purpose, Singapore invested heavily in new types of education, both for children and adults. According to a Global Urban Development report, “More training centers were geared towards the higher-skilled industries such as electronics,” and a new education system was installed, “to ensure that Singapore could form a very high quality and skilled workforce out of the universities and yet at the same time, ensuring that technical training was still available to those who could not excel in the formal education system.”28 Again, the system worked. While its share of manufacturing employment dropped, the services sector in the next few decades rapidly grew, contributing a fifth to GDP in the early 1980s, but almost a third by the mid-2010s. By 2015, Singapore had a GDP per capita exceeding that of both Germany, the economic powerhouse of Europe, and the US, the wealthiest nation on earth.

While Singapore is one of the most remarkable success stories of the past half century, the Southeast Asian nation understands that they will need to continue adapting to changes in the global economy today, where new technologies and service jobs are becoming ever more important. It's why it recently set up a government-led SkillsFuture initiative. Through this system of lifelong learning, Singaporeans of any age can learn new skills to ensure they are prepared for the job market of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Unlike in Denmark though, the system is not achieved by setting up a large state with vast social power and far-reaching programs. “We have a strong government, but not a big government,” Shanmugaratnam said. One of the features of the SkillsFuture initiative, therefore, is that participants mostly have a free choice on which programs to enroll in. In a workshop organized for us by James Crabtree at the National University of Singapore, some policy thinkers made a remark that had led to some discussion in government circles. Must workers really be subsidized to learn how to become florists or cooks, for example? Currently in Singapore, the prevailing notion is that the programs may be uncommon, but they are also worth the cost. One of the features of the ongoing Fourth Industrial Revolution, the reasoning goes, is that it's hard to predict the labor market of the future. Who thought some of the most successful twentysomething professionals today would be YouTubers playing videogames or influencers making 10 second TikTok movies?

When looking at the Singaporean model, there is another important feature to note. It's been achieved by a triad of stakeholders: government, companies, and unions. Since 1965, this trifecta has had a heavy hand in all labor market and industrial policy decision-making. And it did so without major disruptions in economic activity. Strikes in Singapore are extremely rare, yet the labor market is dynamic (it is relatively easy to hire and fire), and the economy has successfully transformed itself at least twice—once in the 1960s and 1970s toward manufacturing and again in the 1980s and 1990s toward services. Such a constructive and dynamic attitude will remain important going forward, Nikkei Asian Review reported recently, because “Singapore will face the highest rate of job displacement resulting from technological disruption in Southeast Asia.”29 But in a sign that this coming technological disruption will not devastate Singapore's society and economy, a survey by accounting firm PwC found that “over 90% of the Singaporean respondents said, they will take any opportunity given by their employers to better understand or use technology.”30 It shows the triple challenge for economies like the US and Western Europe. Governments and companies must invest more in continuous retraining of workers, unions must be stronger but have a cooperative approach to business and government, and workers themselves should be positive and flexible about future economic challenges they and their country face.

A Changing Business Landscape

Tim Wu was still in elementary school in 1980, when he was one of the first of his class to get a personal computer: the Apple II. The now iconic computer propelled creators Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak to stardom and heralded a new era in technology. But for Tim and his brother, the Apple II was first and foremost an exciting way to get acquainted with a new technology. “My brother and I loved Apple, we were obsessed with it,” Wu told us.31 The two preteens would make it their hobby to get the computers chips out, reprogram them, and put them back in. A couple of years later, when computer networks were first introduced, they would set up a dial-up modem, connect to other computers, and create their own networks. Those formative years made the Wus lifelong nerds for technology. Tim's brother eventually went on to work as a programmer for Microsoft, and Tim had an (unpaid) stint at Google. There too, Wu was still very excited. “I was a real believer,” he said. “There was a lot of hope with what Google was trying to do. There was a feeling that we could transcend all dilemmas.”

Today, though now Columbia Law Professor Wu still uses an Apple laptop, iPhone, and Google services every day, he is no longer a fan of the companies they have become. With market valuations that hover around or even well over $1 trillion,32 the companies that once fit into a garage are America's largest publicly traded companies. Apple's personal computers stopped being its top-selling products a long ago, ceding that place to the iPhone. And while it still makes the lion's share of its revenues from selling a sleek line of hardware, including the iWatch, iPad, and iPhone, its copyrighted and well-protected software products and its pioneering App Store now form the beating heart of its ecosystem. Google (now under parent company Alphabet) went from being the leading search provider to a sprawling imperium active in everything from ad sales to shopping, entertainment, and cloud computing. And while many of the early IT companies faded away as time went by, Alphabet, Apple, Microsoft, Facebook, and Amazon consolidated their leading positions, to become the corporate giants of our era.

“The turning point came when these big guys didn't go away, or got too big,” Wu said. “It was when they got into too many markets.” It was advice he gave to Google when he was still friendly with them. “You have this incredible thing,” he told them, “but you need to be careful with adjacent markets.” Wu was trying to be Google's friend, he said, but wanted to keep it out of what he called “morally dubious practices.” The advice fell on deaf ears. The result, he said, is that today the top five Big Tech companies more resemble monopolists like telecom provider AT&T in the 1980s than the upstarts they were not too long ago. They buy or copy competitors to protect their markets, he said, act as both a platform and seller, and favor their own products on their stores. And as with the monopolists of every previous industrial revolution, Wu argues, they stifle the economy and competition while doing so and concentrate wealth and power in the hands of a few, rather than the many. For that reason, Wu claims, these “Big Tech” companies should face one of two tough measures: to be regulated like a natural monopoly or to be broken up.

Wu is far from the only one in America who is likening the situation of Big Tech to the monopolists of previous eras. When I visited US Senator Elizabeth Warren in Washington, DC, at the end of 2018, she was already contemplating a similar stance against the market leaders in many of America's industries, including technology, the pharmaceutical sector, and finance. Wu's colleague at Columbia Law School Lina Khan in 2016 wrote a seminal paper (while at Yale), taking a similar stance: “Amazon's Antitrust Paradox.”33 Economists such as Gabriel Zucman, Emmanuel Saez, Kenneth Rogoff, and Nobel Prize winners Paul Krugman and Joseph Stiglitz have also stated Big Tech has “too much power”34 or needs to be more strictly regulated. Leading journalists including Nicholas Thompson, the editor in chief of Wired, and Rana Foroohar, associate editor of the Financial Times, favor antitrust action against Big Tech too. And even some co-founders of the tech giants that have now come under regulatory scrutiny, including Apple's Steve Wozniak35 and Facebook's Chris Hughes, have said they favor more strict regulation. To Wu, it is the only right attitude. “I always liked the Wozniak Apple,” he said. “They did amazing things.”

But just as there are those like Wu, Warren, and Wozniak who believe Big Tech's monopolies or monopsonies (a variation of a monopoly in which there is only one buyer in a market) need to be regulated more, there are those who believe such actions would prove counterproductive. They point to the fact that many Big Tech services are free or that the prices they offer are the lowest and best in the market (think Amazon). In either case, they say, the best way to deal with these large technology firms is not to break them up or regulate them. Those actions would hurt some of the most innovative companies of the past years and thereby, the innovative power of the US economy. Some also point to an ongoing war for tech hegemony, mostly between the US and China, where excessive restrictions on US companies could make them lose this fight.

I had the opportunity to meet all the leaders of these Big Tech companies over the last years and to follow many of them closely in their journey toward success. For example, I visited Mark Zuckerberg in a warehouse in Palo Alto, when he had just 18 employees, and designated Jack Ma a World Economic Forum “Young Global Leader” when he had just started Alibaba. I am convinced that they, after an initial period of feeling perhaps a bit like Alice in Wonderland, have become increasingly aware of the enormous impact they have on individuals’ lives and identities. And I see among them an increasing readiness to work constructively on responses to the legitimate concerns of society, including regarding data ownership, algorithms, face recognition, and so on. They know it is in their own long-term interest not to neglect these concerns, as they could otherwise be subject to regulations that further harm their future growth.

Who in the end is right in this debate? Are Big Tech and other dominant firms in today's economy helping or hurting workers and consumers? Should we update our competition policies to make them fit for the digital economy? And have we entered a new Gilded Age because of Big Tech, or will we rather enter an innovation winter if we curtail the most successful firms of our age? Looking at economic history through the industrial revolutions lens can help answer these important questions.

Pre-Industrial Revolutions

Before the dawn of the modern era, economies around the world were mostly stagnant. The most significant change in human lifestyle had occurred some 10,000 years ago, when hunter-gatherers settled and became farmers. That change was significant in two ways. Farming led to a stable supply of food and even a regular surplus for the first time,36 and a non-nomadic way of life allowed people to stock food and domesticate animals, providing further sources of nutrition, including meat and milk products. Aided by further technological breakthroughs, such as the development of the plough, the wheel, pottery, and iron tools, this era consisted of a true agricultural revolution. It had major political, economic, and societal consequences.

Socially, the new sedentary lifestyle allowed for the development of villages, cities, societies, and even early empires. Politically, these societies started to see hierarchies for the first time, as the food surplus allowed certain classes of people to live off the foods produced by others. And economically, early trading and specialization led to a modest increase in overall wealth. Almost invariably, the emerging civilizations that ensued consisted of a top class of warriors and spiritual leaders, a middle class of merchants, traders, and specialized workers (making pottery, clothes, and other products), and a large base class of serfs and farmers, who produced foods for themselves and others, most often in a system of subservience to the top classes. It is an early pattern we'll see throughout history: technological breakthroughs lead to a significant increase in wealth, but that surplus almost always gets unevenly distributed and even monopolized by a small group of people at the top of society.

The following millennia saw many changes in political and societal structure, as well as various periods of innovation. On the Eurasian landmass, from China over India and the Arab world to Europe, breakthroughs occurred during medieval times in printing, finance, and accounting, as well as navigation, warfare, and transportation. As we saw in previous chapters, these technological advances spurred on various waves of intercontinental trade and led to a further increase in the lifestyle of peoples, particularly in the top classes. It was the time of the Persian, Ottoman, Mongol, and Ming empires.

In Europe, which lagged the Eurasian trend, the Renaissance and early modern period finally saw a true scientific revolution. It led to great changes in society and politics, including the dominance of European powers in the global economy, the Reformation in European Christianity, and the Peace of Westphalia in European politics. And, with the aid of the compass, sail ships, firepower, and other applications of this scientific revolution, European powers also established a number of global trading empires, epitomized by the gigantic East India Companies we wrote about in the previous chapters. But even with these advances in technology and wealth, the vast majority of people in Europe by the end of the 18th century were still active in farming, their lives having changed little from that of their forebears many centuries ago.

The First Industrial Revolution

This all changed with the arrival of the so-called First Industrial Revolution, primarily in Great Britain. By the 1760s, James Watt and his steam engine were poised to revolutionize industry. Progress was irregular at first, but by the early 19th century Britain's entrepreneurs were well on their way to becoming the world's most successful. In a matter of decades, British steam trains, ships, and machinery took over the world, and Great Britain became the most powerful empire in the world. Entire industries got completely transformed, most notably agriculture and textile manufacturing. Instead of being powered by man or horse, they were now powered by machines, allowing for a multiple increase in yields in agriculture and an even greater multiplier in manufacturing. The British economy—measured in output of final goods—started to grow by several percentage points per year, rather than the 0.1 or 0.2 percent, which was the norm in previous centuries. The population grew rapidly. And while there were many more mouths to feed, fewer people (and horses) were needed in the agricultural sector. By the end of the 19th century, more than half of the population had therefore moved to industrial cities like London, Manchester, or Liverpool, and a majority of them was active in the factories.

The ones who benefited most from this First Industrial Revolution were Britain's capitalist entrepreneurs. Capitalism was nothing new. It had existed in Europe at least since Venetian merchants pooled their risk of shipping in the medieval Mediterranean trade—but was now mainly used to fund factories and their machines, rather than trade. Those who had enough capital at hand—often large landowners, successful merchants, and members of aristocratic families—could invest in new technologies and start successful companies. With a world market now at their disposal, they pocketed huge profits. And as the labor needed to operate machines was not as specialized as that needed to manufacture goods by hand, these early industrialists had a bargaining power over workers, which led to exploitative situations (and that was only in Britain, the wealthiest country of the time; the countries whose craft manufacturing was decimated, such as India and China, were much worse off, as there were virtually no winners).

As the 19th century progressed, the technologies of the First Industrial Revolution also spread to other countries, mainly in continental Europe (most notably Belgium, France, and Germany) and Britain's former colony across the North Atlantic Ocean, the United States. The technological transformation coincided with a political, economic, and social transformation here too. By the end of the 1800s, the plight of ordinary workers had become so problematic in England, Belgium, France, and Germany, that some members of the new leading classes decried the excesses. Les Misérables was written, highlighting the exploitative conditions in which regular Frenchmen had to work. German émigrés Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels wrote newspaper articles and even books about the fate of the proletariat in industrial England, which was all but positive. And Charles Dickens, writing a few decades earlier, most famously wrote it was not just the “best of times,” but also the “worst of times,” the “season of Darkness,” and the “winter of despair.”37 Was it the result of industrialization or globalization? In truth it was probably both. As we saw in the previous chapter, workers started to unite against the injustices they faced and demanded political rights, better wages and working circumstances, and even an overthrow of the new societal hierarchy, in which industrialists had replaced kings and priests at the top of society and factory workers had replaced serfs and other small farmers at the bottom.

In America, too, the first Industrial Revolution led to an untenable situation. The technological advances in transport, finance, and energy led to the formation of oligopolies and monopolies: companies with the most capital and initial resources could best afford to deploy the latest technology at the greatest scale, offer the best services, and in turn win a higher market share, make the most profit, and outcompete or buy up other companies. In the transportation sector, for example, it led to a dominant position for the railroad companies connecting the Midwest to New York, controlled by Cornelius Vanderbilt, a tycoon also active in shipping. In the energy sector, it allowed the astute John D. Rockefeller to come from almost nothing to build the world's largest oil company, Standard Oil, and later also created the first business trust (Standard Oil today lives on in ExxonMobil, still America's largest oil company). In the steel industry, it enabled the Scottish-born American Andrew Carnegie to create the forerunner of U.S. Steel, which later became the monopolist of steel production in the US. In coal production, it led to Henry Frick establishing the Frick Coke Company, which controlled 80 percent of the coal output in Pennsylvania,38 and taking the helm at several other conglomerates of the time. And in banking, it created a situation where magnates like Andrew Mellon, of BNY-Mellon fame, and John Pierpont Morgan, founder of what is today JPMorgan Chase, could build some of the largest financial firms America had ever seen.

Today, we know many of these industrial tycoons for their societal contributions, which include Rockefeller Center, Carnegie Hall, and many philanthropic organizations, which are still active today. But at the end of the 1880s, they were best known for their opulent wealth and often questionable business practices. While their wealth in today's terms would exceed that of even Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos, that of the man and woman in the street was often non-existent. Extreme poverty was the norm in the tenement houses of big cities like New York, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Chicago. Worker wages were low and bargaining power absent in the face of the trusts’ economic power. The contrast between rich and poor living standards was so shocking that Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner in 1873 wrote a satirical book about it, which became a nickname for the era: The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today. By the early 1900s, the situation also led to the first era of “populism” in American politics. The People's Party in 1892 became the first third party to win electoral seats in the presidential election, coming up for the rights of “rural and urban labor,” and against the “moral, political and material ruin” the then-leading class had allegedly brought about. In 1896 the candidate of this original Populist Party even became the Democratic National Convention's official presidential candidate, though he (William Jennings Bryan) did not win the presidential election—he lost to Republican William McKinley.

This First Industrial Revolution brought about incredible gains in wealth in those countries leading it but also incredible suffering among the poor in industrialized nations. But it was also bad news for those living in countries which fell behind in the Industrial Revolution, including the Asian countries that had until then led the world in GDP: China, Japan, and India. There, the entire political systems collapsed, and chaos or colonization followed. In America and Western Europe though, when the popular backlash grew so great that it was impossible to ignore, action was taken to root out the excesses of wealth and put a limit to the suffering of the working class. In Europe, from the UK to Germany, socialist parties were elected to government after universal suffrage was introduced in a series of reforms from the 1870s to the 1920s. Conservative and Christian-Democratic parties also adopted more socially conscious measures. Otto von Bismarck's government in Germany, for example, which had a conservative bent, implemented nevertheless a series of social reforms in the 1880s, which were the kernel of the social security Western Europe knows today.

In America, by contrast, the focus in those early years was less on providing social security and more on enforcing antitrust. (The Social Security program wouldn't arrive until 1935, on the back of the Great Depression,39 which left tens of millions without jobs, food, and homes.) By 1890 it dawned on lawmakers they needed to address the hurtful actions of the robber barons, which corrupted politics and monopolized entire industrial sectors. The first antitrust law was passed that year and was amended several times in subsequent years. In 1914, two more important laws were passed, including one which created the Federal Trade Commission. Together, these laws had to make sure the trusts of men like Rockefeller could no longer create de facto monopolies, either by buying up all their competitors or by colluding with them on prices. The most famous breakup that followed was that of Standard Oil in 1911, which “controlled over 90 percent of the refined oil in the United States”40 by the turn of the century. The company was split up into 34 different parts, some of which today survive as brands or separate companies, including ExxonMobil (once separated as Exxon and Mobil), Chevron, and Amoco. Other industries also faced regulatory scrutiny. Monopoly power was bad for innovation, regulators believed, it was bad for consumers, and it was bad for competition. It needed to be stopped.

The Second Industrial Revolution

As so often in economic and political history, the actions taken by governments in the industrialized world proved mostly successful in solving the problems of the present and the past but not so much in solving those of the future. A Second Industrial Revolution had taken place, and the technologies it spawned, the internal combustion engine and electricity, led to a new set of products, such as cars, planes and electric networks, and the telephone. In time, they would come to create, reshape, and dominate industries, much as the technologies of the First Industrial Revolution had done before them. But geopolitical friction in 1914 interrupted the economic dynamics of the industrialized world. In the First and Second World Wars, technology was seen as more of a destructive power than an economic driver. The First World War was the last one in which horses were strategically deployed. The Second World War was the first in which tanks and planes dominated the battlefield. Tens of millions of people died, many of them through tools of the latest technologies.

By 1945, a new world emerged, and this time, technology would go on to play a much more universally positive role in the West, especially for blue-collar workers and the middle class, economist Carl Frey pointed out in his book The Technology Trap. The automobile on both sides of the Atlantic quickly became a mass market means of transportation, affordable as much for the ordinary worker as for the upper class. Electricity became standard in every home, and its applications included the washing machine, air conditioner, and refrigerator. They made life easier, healthier, and cleaner for everyone and greatly helped to emancipate women. And the industries that electricity and transportation helped create opened many middle-class job opportunities, even for medium- and low-skilled workers. Factory machines this time were complementary to workers, relieving them from heavy physical duty while still requiring them in great numbers. And drivers, telephone operators, secretaries, and cashiers all were in high demand in an economy that increasingly held the middle between one based on manufacturing and one based on services.

This explosion of widespread wealth, which was accompanied by a baby boom, allowed countries to further strengthen their social security systems and education, health care and housing policies. In America, President Lyndon Johnson announced a Great Society program.41 It aimed at eliminating poverty and racial issues through initiatives such as the War on Poverty, introduced health programs such as Medicare and Medicaid, and mandated the building of many new schools and colleges, as well as the establishing of grants and a Teacher Corps. In Europe, the welfare state was introduced, with often universal free health care, free education, and state-subsidized housing.

All the while, antitrust action remained on the political agenda. In America, the newly emerged telecom industry had consolidated to such an extent, that by the 1960s, the Bell Company (now AT&T) was a de facto monopoly. Using the antitrust legislation put in place after the First Industrial Revolution, it too was broken up, lowering prices and improving service drastically in the decades after and unleashing a new wave of innovation, which ultimately led to mobile telephony. In Europe, countries chose a more direct form of regulation, setting up electricity and telecom providers as state-owned monopolies. This too ensured any profits beyond market rate would ultimately benefit society, albeit indirectly. But this stifled innovation and competition, as the state-owned enterprises over time lost their appetite for providing better service or a lower price, lacking a strong competitive incentive.

The auto industry became competitive enough to not require antitrust action, although now we know they used their political influence and economic power to lobby for less-than-optimal outcomes in the transportation sector, notably by favoring funding for cars and buses and their infrastructure over that for trains and trams and by delaying the introduction of electric motors. But market concentration did remain relatively low, partially because of increased international competition over time. The sector also created directly and indirectly millions of jobs. And it offered a ticket to a middle-class lifestyle for tens of millions more. Automobile manufacturers for those reasons avoided regulatory scrutiny and were among the most revered companies all over the world.

Perhaps as consequence of the much more positive role technology and companies played in this Western golden age, people's ideological views on capital versus labor and man versus machine softened significantly. Importantly, economists too touted more the positive effects of enterprises and their innovations in societal and economic development. Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter already in the 1940s saw a world emerge in which “creative destruction”42 led to the breakdown of old companies and their products, by new companies and their breakthrough technologies. The car replaced the horse, the plane replaced the ship, and electric household devices replaced domestic workers. Milton Friedman and his colleagues at the University of Chicago (the so-called Chicago School) went a step further. Friedman believed in the naturally positive role of business in the economic system. An invisible hand ensured that markets would always have an optimal outcome, maximizing utility for society. It meant that “there is one and only one social responsibility of business,” Friedman wrote in a 1970 New York Times essay.43 It is “to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game.” In the context of the Second Industrial Revolution and the largely positive role its companies played in economic and social development at the time, that was understandable. But it would prove to have more negative consequences just a few decades later, as the positive impact of business on society increasingly faded again in the Third and Fourth Industrial Revolution.

The Third Industrial Revolution

In the 1970s and 1980s, as the antitrust case against Bell Company went through political and judiciary hoops, two small computer companies were created in Albuquerque and Cupertino garages that would go on to alter the course of economic history. Microsoft and Apple Computer initially built personal computers, like the one Tim Wu got from his parents. But as the 1980s progressed, the companies became increasingly famous for their software, including MS-DOS, Windows, and Mac OS. And in the 1990s Microsoft and Apple helped bring the Internet into the office and living room. Along the way, the personal computer transformed from an expensive and bulky niche device to the most important tool of workers in the modern economy. This revolution, which brought the world information technology (IT) and the Internet, and all the applications and industries that went hand in hand with it, came to be known as the Third Industrial Revolution.

The Third Industrial Revolution greatly enhanced the productivity of white-collar workers. They could process much more information much faster and instantaneously coordinate with co-workers anywhere, at the touch of their fingertips. And it helped to unleash the greatest wave of globalization in history: manufacturing could be decoupled from back-office, a company headquarters from its global value chain. This IT and Internet revolution is what allowed countries such as China, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Mexico to integrate in the world economy, helping hundreds of millions of people enter the global middle class.

Its net effect on a global scale was undoubtedly positive. In the First and Second Industrial Revolutions, wealth was accumulated at the top and in the middle of Western industrialized nations. In this Third Industrial Revolution, emerging markets finally got a fair share of the pie. Economists Christoph Lakner and Branko Milanovic showed the effect in their well-known “elephant” graph.44 It illustrated that from 1988, as the IT revolution was in full swing, until 2008, when the Internet had shaken up the world's supply chains, the global middle class benefited, as did the 1 percent in industrialized nations. But the Western middle class paid a price. Due to the IT revolution, their jobs could as well be done by lower-wage workers elsewhere, putting pressure on both their jobs and salaries.

That insight can be seen in the most recent “elephant” graph, which has been last updated for the World Inequality Report 2018 (see Figure 6.2). It shows the percentage income growth (on the vertical axis) of each percent of the global population (ranked from poorest to richest, on the horizontal axis). We can see that those largely between the 10th and the 50th percentile of the income distribution (which includes many of the emerging middle classes of China, India, ASEAN and elsewhere) saw very positive income growth, of often over 100 percent. They form the “back” of the elephant. The top one percent—the global elite, including the professional classes in the West—also had a high income growth rate, with the 0.1 and 0.01 percent benefiting even more, relatively speaking. They form the tip of the elephant's trunk. These two groups were by and large beneficiaries of globalization.

Those in the 60th to 90th percentile of the global income distribution however—including many in the working and middle classes of Western countries such as the US, the UK, and Western Europe—had an income growth rate that was much lower. Over the past 35 years, their average incomes grew by little over 1 percent per year, if that. Many felt no net benefit of globalization at all, and quite a few even lost their well-paid blue-collar jobs because of outsourcing to lower-income countries. And the very poorest of the poor, in the first few percentiles of the income distribution, didn't advance much either (their income growth is not shown in the graph).

Figure 6.2 The Elephant Curve of Global Inequality and Growth

Source: World Inequality Report (2018). Inspired by Lakner and Milanovic, World Bank Economic Review (2015). Elephant first added by Caroline Freund45 (Peterson Institute for International Economics).

But the Third Industrial Revolution had another effect. It introduced the network effect as a competitive force, locking users into networks used by a majority of others, and heightened the importance of intellectual property. Microsoft was a case in point. As personal computers conquered the office, Microsoft's Windows became the dominant operating system, Office the dominant software, and Internet Explorer the dominant web browser. That was largely thanks to its functionality and an early agreement with IBM, but Microsoft was also quick to lock consumers in to their products: it pre-installed Internet Explorer on Windows, effectively bundling the two together, and made it hard for non-Microsoft users to access files in its Office programs, or its Windows Media Player. It got the attention of US and European antitrust authorities: Was Microsoft misusing its power? On June 7, 2000, after a seven-year investigation, the US District Court in Washington, DC, reached its verdict: Yes, Microsoft had misused its monopoly power and should be broken up in two separate companies, one producing the operating system, and the other making software.46 In 2004, the European Commission also found Microsoft guilty of anti-competitive practices, in a case related to its Windows Media Player. It ordered a fine of about 500 million euros.47 But while Microsoft paid the European fine, the highest ever given to a company until that point, it did successfully appeal the US District Courts decision to break it up. In 2001, a new verdict was reached: Microsoft could continue to operate as one company.

According to Tim Wu, it was a turning point in the antitrust actions taken by United States and Europe. The EU Commission, emboldened by its successes, became increasingly aggressive in protecting consumer interests and combatting monopolies. In its pursuit to create a common European market, it also opened national markets, leading to increased competition, lower prices, and better services in many industries. In the US, by contrast, market concentration kept increasing in the following years, as antitrust authorities mostly stood by the sidelines. Indeed, in the two decades since the Microsoft ruling, journalist David Leonhard observed in the New York Times (citing research by economist Thomas Philippon), “a few companies have grown so large that they have the power to keep prices high and wages low. It's great for those corporations—and bad for almost everyone else.”48 The resulting situation is one of factual oligopolies:

It would be wrong to ascribe this evolution merely to technology or globalization, economists such as Philippon, and legal scholars such as Wu and Lina Khan also argued. Technology did of course allow these companies to continue their global growth. It created the tools for them to entrench their market positions. But it was the state which allowed this to happen. How? First, by focusing its antitrust actions in the technology sector on consumer prices, as the Chicago School had argued for a few decades earlier, it missed the broader picture of what was happening. In the case of services such as Facebook and Google, the consumer price stopped being the relevant yardstick. The consumer effectively became the product. The use of many services was free, but the flip side was that users were targeted by personalized ads. In the online ad market, then, the Big Tech firms did set the price, lacking competition. But because this market is less visible, it didn't prompt the same regulatory scrutiny. In Europe, by contrast, DG Comp, the EU competition watchdog, looked at broader market indicators, allowing it to intervene quicker. Second, having locked in consumers through the network effect (as consumer, you don't want to be the only one not using a particular social network), Big Tech has also been able to put in place rules on the use of personal data that were previously unheard of. As these practices were simply non-existent in previous industrial revolutions, there was until recently no template for regulators to act against them.

As indicated, the European Commission offered an alternative way to deal with these situations. Its competition commissioner handed out more and bigger fines to monopolistic companies since the landmark Microsoft case. Google, Intel, and Qualcomm all got fined over $1 billion50 for anti-competitive practices, with Google even given a second billion euro fine by the antitrust regulator in March 2019, for “abusing practices in online advertising.”51 The Commission also acted against cartels, including in truck manufacturing,52 TV tubes production, foreign exchange, car repair, elevators, vitamins, and airfreight, demanding more than 26 billion euros in combined fines since the year 2000.53 And it actively blocked mergers, ensuring large firms continue to feel competitive pressure from new entrants. In recent years, it notably stopped the mergers of Alstom and Siemens, two major rail companies, and the creation of a joint venture between steel giants Tata Steel and ThyssenKrupp. Of the 200 mergers it took a crucial second-phase decision on since 1990, 30 were blocked, 133 were deemed compatible if certain conditions were met, and only 62 mergers were given a full green light.54 In the coming years, the Financial Times reported, competition commissioner plans to be even more aggressive, particularly with regards to so-called Big Tech firms: “We will be much more aware as to what [is] needed […] in a market that has been plagued with illegal behaviour by one or more companies,” she said,55 adding that “breaking up companies [. . .] is a tool that we have available.” She is right to take this assertive stance, Thomas Philippon argues, because it means “E.U. consumers are better off than American consumers today [. . .] The E.U. has adopted the U.S. [antitrust] playbook, which the U.S. itself has abandoned.”56

Yet, even if an approach like the one adopted in Europe seems to be the right one to best protect citizens’ interests, it may hurt European tech firms’ competitiveness on a global level. In the case of the proposed Alstom-Siemens merger, for example, the market share of the combined firm would have been problematic in the European market, but its resulting scale would have allowed the company to more effectively compete on the global level, where it is now facing an even larger, state-backed Chinese competitor (CRRC),57 as well as similar-sized Japanese and Canadian firms such as Hitachi and Bombardier.

Partially as a result of this increased scrutiny on the European level, European tech firms have not been able to truly break through on the global stage in recent years. Among the 10 most valuable tech companies in the world in 2020, six came from the US, and four from Asia. Could companies from Europe and other regions compete with these giants? The optimal way to create a level-playing field, of course, would be a more international policy and regulatory approach, possibly integrating antitrust measures into a deeply reformed World Trade Organization. But given the difficulties that the organization is facing, this may seem like an unlikely outcome in the short run.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution

Even as many technologies of the Third Industrial Revolution are still playing out in the market, we have entered a Fourth Industrial Revolution. As I wrote back in 2016:

The technologies of the Fourth Industrial Revolution once again have the possibility to greatly enhance global wealth. That is because they are likely to turn into general-purpose technologies (GPTs) such as electricity and the internal combustion engine before them. The most powerful of these GPTs is likely to be artificial intelligence, or AI, according to economists such as Eric Brynjolfsson.59 Already, major tech companies from countries such as China are using AI applications to leapfrog the leading companies from the US. Companies such as Alibaba, Baidu, and Tencent, technology entrepreneur and investor Kai-Fu Lee told us, are rapidly catching up to American AI giants such as Amazon, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft and in some instances already have superior applications. They could help China develop and its people prosper.

As in previous eras, these technologies could just as well increase inequality and social and political rifts, which could bring our existing society close to collapse. Already, companies such as Facebook are facing criticism that their algorithms are designed to sow division and have contributed to the great schism in American society, which is characterized by contentious opposition between the political left and right. This may well just be the beginning of much worse to come as people spend more time online and face ever more interactions with artificial intelligence (AI). Moreover, the advances in biotechnology and medical science could amplify inequality to levels never seen before, improving the lives and even bodies of wealthier humans to the point of creating a biological divide as well as a wealth divide. And technology could be applied to commit cyberwarfare too, with severe economic and social consequences.

To avoid the worst and achieve the best possible outlook, all stakeholders should remember the lessons from the past, and governments should shape inclusive policies and business practices. The challenge in regulating technological breakthroughs is often the speed of innovation. Governmental processes take time and require deep understanding of the innovations. As a frustrated chief executive once expressed to me: “Business moves in an elevator lifted by the force of creativity; government and regulatory agencies take the stairs of incremental learning.” This situation poses a particular responsibility to companies in ensuring that all technological advances are well understood, not only in terms of their functionality for individual users but also what they mean for society more broadly.

This is the purpose of the World Economic Forum Centre for the Fourth Industrial Revolution in San Francisco, which was created in 2017. Its goal is to develop policy frameworks and advance collaborations that accelerate the benefits of science and technology.”60 It brings together all stakeholders that are relevant in this process, that is to say government, companies, civil society, youth, and academia. Several companies immediately signed up with the Centre as founding members, and from the start it became clear that they are open to having others help them help society. And following a wave of interest from governments from around the world, who were eager to understand the effect of new technologies and how best to regulate them, we opened sister centers in China, India, and Japan, as well as affiliate centers in Colombia, Israel, South Africa, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.

Going forward, we should remember that technology is never universally good or bad; all depends on how we deploy it. Every stakeholder has its part to play, from government to business to society at large. Indeed, even entrepreneurs starting out with the best intentions can end up leading companies that do more harm than good. And while innovative companies, operating in a free market, are a great motor of economic progress, an equally innovative and powerful government—which keeps the best interests of society in mind—is its best ally. As Mariana Mazzucato argued in her book The Value of Everything,61 a strong government should not limit itself to regulation, it can also be a fundamental force of innovation and societal added value itself. Among the technologies that were initiated by government-sponsored research, are the Internet and GPS (DARPA), the world wide web (CERN), touch screen technology, and semi-conductors, all of which power some of the most innovative products of today, such as Apple's iPhone.62

In the end, we will have no choice than to embrace innovation and accept help from whoever is able to offer it. But we should give stronger incentives to those entrepreneurs who were once small and innovative, to not betray their own identity, and become big and monopolistic. It is only when technologies are shared widely, that they reach their full potential. And that will be more crucial than ever before in the age of AI. The ownership of data in this case will be a critical component, and we must ensure that it does not reside with monopolistic firms. That is Tim Wu's advice to the Big Tech firms he used to love, as well as the giant corporations dominating other industries. “I always liked small business,” he said. “So when these companies got too big, I became an antitrust crusader.”63

Just as important as the market structure, however, is that the value that is created is effectively shared. In previous industrial revolutions, industrial firms operated mostly in national markets. It meant that governments could intervene to ensure that value was equitably shared between all market participants. With AI, however, the picture looks different. Many companies active in Internet technology offer their services for free, meaning there is no price to regulate or tax to levy at the product level. And with almost all of the leading tech firms being American or Chinese but globally active, many national governments have not been able to tax profits either, which are often shielded through transfer pricing and IP-related exemptions. If citizens and governments everywhere want to share in the wealth creation of these companies, different regulatory and tax frameworks will need to be set up and implemented.

And then there is a final consideration: even if we get the Fourth Industrial Revolution right, there is still another global crisis we need to address as well: the ongoing climate crisis.

Notes

- 1 « Danmark i verdens robot top-10 », Dansk Metal, January 2018, https://www.danskmetal.dk/Nyheder/pressemeddelelser/Sider/Danmark-i-verdens-robot-top-10.aspx.

- 2 “Why American Workers Need to Be Protected From Automation,” Bill de Blasio, Wired, September 2019, https://www.wired.com/story/why-american-workers-need-to-be-protected-from-automation/.

- 3 “Robots Are the Ultimate Job Stealers. Blame Them, Not Immigrants,” Arlie Hochschild, The Guardian, February 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/feb/14/resentment-robots-job-stealers-arlie-hochschild.

- 4 The Fourth Industrial Revolution, Klaus Schwab, Penguin Random House, January 2017, https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/551710/the-fourth-industrial-revolution-by-klaus-schwab/.

- 5 “The Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerization?” Carl Frey and Michael Osborne, Oxford University, September 2013, https://www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk/downloads/academic/The_Future_of_Employment.pdf.

- 6 The Technology Trap: Capital, Labor, and Power in the Age of Automation, Carl Frey, Princeton University Press, June 2019, https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691172798/the-technology-trap.

- 7 “If Robots and AI Steal Our Jobs, a Universal Basic Income Could Help”, Peter H. Diamandis, Singularity Hub, December 2016, https://singularityhub.com/2016/12/13/if-robots-steal-our-jobs-a-universal-basic-income-could-help/.

- 8 Interview with Claus Jensen by Peter Vanham, May 2019

- 9 Even if jobs disappeared in one part of the industry, which happened when ships were no longer mainly built by humans but by robots, having a long-term vision of change helped him keep a positive and constructive outlook. Workers still need to oversee construction, they still need to repair engines, and they still needed to make sure all parts fit together. If Danish workers were the best in the world, Denmark could remain the global center of ship building and repair. It was in the DNA of his union to have such a positive perspective. “My union was founded in 1888, and our first chairman said the same things that I do today,” he said. “We change technology, but we don't change our opinion.”

- 10 Interview with Robin Løffmann by Peter Vanham, Copenhagen, November 2019.

- 11 Interview with Thomas Søby by Peter Vanham, Copenhagen, November 2019.

- 12 Unemployment, Statistics Denmark, consulted in October 2020, https://www.dst.dk/en/Statistik/emner/arbejde-indkomst-og-formue/arbejdsloeshed.

- 13 “Inequality in Denmark through the Looking Glass,” Orsetta Causa, Mikkel Hermansen, Nicolas Ruiz, Caroline Klein, Zuzana Smidova, OECD Economics, November 2016, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/inequality-in-denmark-through-the-looking-glass_5jln041vm6tg-en#page3.

- 14 “How Many US Manufacturing Jobs Were Lost to Globalisation?” Matthew C. Klein, Financial Times, December 2016, https://ftalphaville.ft.com/2016/12/06/2180771/how-many-us-manufacturing-jobs-were-lost-to-globalisation/.

- 15 Trading Economics, United States Labor Force Participation Rate, with numbers supplied by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, https://tradingeconomics.com/united-states/labor-force-participation-rate.

- 16 Trading Economics, Denmark Labor Force Participation Rate, https://tradingeconomics.com/denmark/labor-force-participation-rate.

- 17 Interview with Thomas Søby by Peter Vanham, Copenhagen, November 2019.

- 18 OECD, Directorate for Employment, Labour and Social Affairs, Employment Policies and Data, Skills and Work dashboard, http://www.oecd.org/els/emp/skills-and-work/xkljljosedifjsldfk.htm.

- 19 Interview with Heather Long by Peter Vanham, Washington, DC, April 2019.

- 20 Ibidem.

- 21 Interview with Thomas Søby by Peter Vanham, Copenhagen, November 2019.

- 22 “How Today's Union Help Working People: Giving Workers the Power to Improve Their Jobs and Unrig the Economy,” Josh Bivens et al., Economic Policy Institute, August 2017, https://www.epi.org/publication/how-todays-unions-help-working-people-giving-workers-the-power-to-improve-their-jobs-and-unrig-the-economy/.

- 23 “Singapore Society Still Largely Conservative but Becoming More Liberal on Gay Rights: IPS Survey,” The Straits Times, May 2019, https://www.straitstimes.com/politics/singapore-society-still-largely-conservative-but-becoming-more-liberal-on-gay-rights-ips.

- 24 “Singapore: Crazy Rich but Still Behind on Gay Rights,” The Diplomat, October 2018, https://thediplomat.com/2018/10/singapore-crazy-rich-but-still-behind-on-gay-rights/.

- 25 Interview with Senior Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam by Peter Vanham, Singapore, July 2019.

- 26 “Singapore's Economic Transformation,” Gundy Cahyadi, Barbara Kursten, Dr. Marc Weiss, and Guang Yang, Global Urban Development, June 2004, http://www.globalurban.org/GUD%20Singapore%20MES%20Report.pdf.

- 27 “An Economic History of Singapore—1965–2065,” Ravi Menon, Bank for International Settlements, August 2015, https://www.bis.org/review/r150807b.htm.

- 28 “Singapore's Economic Transformation,” Gundy Cahyadi, Barbara Kursten, Dr. Marc Weiss, and Guang Yang, Global Urban Development, June 2004, http://www.globalurban.org/GUD%20Singapore%20MES%20Report.pdf.

- 29 “Singapore Faces Biggest Reskilling Challenge in Southeast Asia,” Justina Lee, Nikkei Asian Review, December 2018, https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/Singapore-faces-biggest-reskilling-challenge-in-Southeast-Asia.

- 30 “PwC's Hopes and Fears Survey,” p. 4, PwC, September 2019, https://www.pwc.com/sg/en/publications/assets/new-world-new-skills-2020.pdf.

- 31 Interview with Tim Wu by Peter Vanham, New York, October 2019.

- 32 “The 100 Largest Companies by Market Capitalization in 2020,” Statista, consulted in October 2020, https://www.statista.com/statistics/263264/top-companies-in-the-world-by-market-capitalization.

- 33 Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox, Lina M. Kahn, The Yale Law Journal, January 2017

- 34 “Big Tech Has Too Much Monopoly Power—It's Right to Take It On,” Kenneth Rogoff, The Guardian, April 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/apr/02/big-tech-monopoly-power-elizabeth-warren-technology; Quote: “Here are titles of some recent articles: Paul Krugman's “Monopoly Capitalism Is Killing US Economy,” Joseph Stiglitz's “America Has a Monopoly Problem—and It's Huge,” and Kenneth Rogoff's “Big Tech Is a Big Problem”; “The Rise of Corporate Monopoly Power,” Zia Qureshi, Brookings, May 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2019/05/21/the-rise-of-corporate-market-power/.

- 35 “Steve Wozniak Says Apple Should've Split Up a Long Time Ago, Big Tech Is Too Big,” Bloomberg, August 2019, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/videos/2019-08-27/steve-wozniak-says-apple-should-ve-split-up-a-long-time-ago-big-tech-is-too-big-video.

- 36 Some scholars do dispute this notion. Yuval Noah Harari, for example, is much less upbeat about the impact of the agricultural revolution on the quality and quantity of food supply on people.

- 37 A Tale of Two Cities, Charles Dickens, Chapman & Hall, 1859.

- 38 “The Emma Goldman Papers,” Henry Clay Frick et al., University of California Press, 2003, https://www.lib.berkeley.edu/goldman/PublicationsoftheEmmaGoldmanPapers/samplebiographiesfromthedirectoryofindividuals.html.

- 39 “Historical Background and Development Of Social Security,” Social Security Administration, https://www.ssa.gov/history/briefhistory3.html.

- 40 “Standard Ogre,” The Economist, December 1999, https://www.economist.com/business/1999/12/23/standard-ogre.

- 41 “The Presidents of the United States of America”: Lyndon B. Johnson, Frank Freidel and Hugh Sidey, White House Historical Association, 2006, https://www.whitehouse.gov/about-the-white-house/presidents/lyndon-b-johnson/

- 42 Term coined in “Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy”, Joseph Schumpeter, Harper Brothers, 1950 (first published 1942)

- 43 “A Friedman Doctrine—The Social Responsibility Of Business Is to Increase Its Profits,” Milton Friedman, The New York Times, September 1970, https://www.nytimes.com/1970/09/13/archives/a-friedman-doctrine-the-social-responsibility-of-business-is-to.html.

- 44 Global Income Distribution From the Fall of the Berlin Wall to the Great Recession, Christoph Lakner and Branko Milanovic, World Bank, December 2013, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/914431468162277879/pdf/WPS6719.pdf

- 45 “Deconstructing Branko Milanovic's ‘Elephant Chart’: Does It Show What Everyone Thinks?” Caroline Freund, PIIE, November 2016, https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economic-issues-watch/deconstructing-branko-milanovics-elephant-chart-does-it-show.

- 46 US District Court for the District of Columbia - 97 F. Supp. 2d 59 (D.D.C. 2000), June 7, 2000, https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp2/97/59/2339529/.

- 47 Commission Decision of May 24, 2004 relating to a proceeding pursuant to Article 82 of the EC Treaty and Article 54 of the EEA Agreement against Microsoft Corporation, Eur-Lex, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:32007D0053.

- 48 “Big Business Is Overcharging You $5,000 a Year,” David Leonhardt, The New York Times, November 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/10/opinion/big-business-consumer-prices.html.

- 49 Ibidem.

- 50 “The 7 Biggest Fines the EU Have Ever Imposed against Giant Companies,” Ana Zarzalejos, Business Insider, July 2018, https://www.businessinsider.com/the-7-biggest-fines-the-eu-has-ever-imposed-against-giant-corporations-2018-7.

- 51 Antitrust: Commission fines Google €1.49 billion for abusive practices in online advertising, European Commission, March 2019, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_19_1770.

- 52 Antitrust: Commission fines truck producers € 2.93 billion for participating in a cartel, European Commission, July 2016, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/es/IP_16_2582.

- 53 Cartel Statistics, European Commission, Period 2015–2019, https://ec.europa.eu/competition/cartels/statistics/statistics.pdf.

- 54 Merger Statistics, European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/competition/mergers/statistics.pdf.

- 55 “Vestager Warns Big Tech She Will Move beyond Competition Fines,” Javier Espinoza, Financial Times, October 2019, https://www.ft.com/content/dd3df1e8-e9ee-11e9-85f4-d00e5018f061.

- 56 https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/10/opinion/big-business-consumer-prices.html.

- 57 “The Alstom-Siemens Merger and the Need for European Champions,” Konstantinos Efstathiou, Bruegel Institute, March 2019, https://www.bruegel.org/2019/03/the-alstom-siemens-merger-and-the-need-for-european-champions/.

- 58 The Fourth Industrial Revolution, Klaus Schwab, January 2016.

- 59 “Unpacking the AI-Productivity Paradox,” Eric Brynjolfsson, Daniel Rock and Chad Syverson, MIT Sloan Management Review, January 2018, https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/unpacking-the-ai-productivity-paradox/.

- 60 Centre for the Fourth Industrial Revolution, World Economic Forum, https://www.weforum.org/centre-for-the-fourth-industrial-revolution.

- 61 Interview with Tim Wu by Peter Vanham, New York, October 2019.

- 62 The Value of Everything, Mariana Mazzucato, Penguin, April 2019, https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/280466/the-value-of-everything/9780141980768.html.

- 63 “One of the World's Most Influential Economists Is on a Mission to Save Capitalism from Itself,” Eshe Nelson, Quartz, July 2019, https://qz.com/1669346/mariana-mazzucatos-plan-to-use-governments-to-save-capitalism-from-itself/.