4

Formal Information Research

Activities in strategic or economic intelligence are inseparable from access to information. Without wishing to be exhaustive, since this is not the aim of this book, it is still necessary to set out a number of facts on this research, to provide practitioners with topics for reflection and action. In the domain of economic intelligence, the businesses and institutions involved should question their relationship with information. This may be done using the work of Timothy Powell [POW 95] on information metabolism as a starting point.

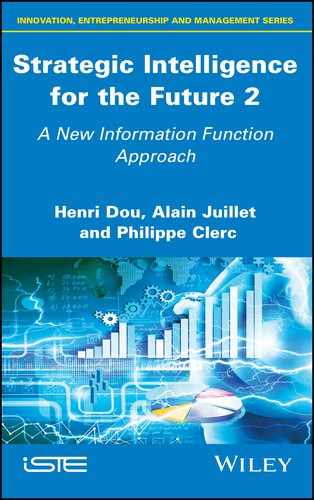

Figure 4.1. Positioning the business

Figure 4.1 makes it possible to focus on the capacities needed on two specific points: the capacity to seek information and the capacity to analyze it. Implementing a system for analysis, discussion with experts; if the information provided to them is incomplete or indeed biased at the outset, it will not lead to good results.

4.1. The importance of the time factor in scientific data

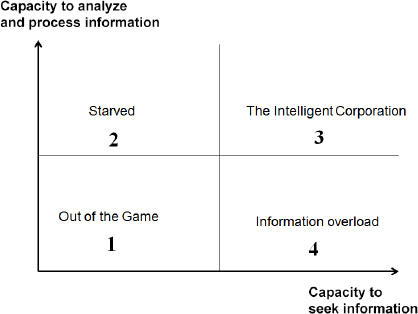

It can be seen that in the majority of cases, the time between the idea and publication of the work to which it gave rise is around two years.

This has an important implication for strategy. In fact, it is certainly necessary to know which institutions or researchers are working in a domain that interests us, but what is still more important is to know what is happening now, which subjects these institutions and researchers are working on, and not what happened two years ago. This “need”, which should be considered particularly important in economic intelligence and strategic information research, has resulted in multiple activities: short and quickly–published communications, colloquia and symposia, informal meetings, think tanks, trainees “sent” to some laboratories, etc. We will see that information analysis, groupings and various correlations enable us to properly select laboratories or institutions and the individuals that work in those domains that interest us. But from this summary, we should, so far as possible, be familiar with the means of reaching this objective. In our case, we limit ourselves to strategies that are ethically acceptable, including going to colloquia and asking questions, reading pre-prints or reports from symposia, making visits, consulting these institutions or researchers’ Internet sites, etc. The traceability of research actors in social network is also a significant path.

4.2. Different information typologies

The importance of the time factor influences information typology. We can thus distinguish formal sources of information or secondary information sources, often called written information and informal information, or primary information sources often called human information. Scientific information, since it is generally published and validated, mainly involves written information. Then, when we consider R&D, or the economy and markets, the percentage of human informations tends to grow rapidly.

It is also believed that formal information is published and validated information – such as scientific publications, theses, books (even though these are not necessarily validated by peer review) – reports, often from scientific institutions or requested from groups of experts by governments. However, informal information should be validated as information, but also assessed according to its source. This informal information, often obtained via human networks, has particular importance, since it lies closest to action. This is the information that, when validated, “shortens the time factor”.

The same goes for information from social networks. This can be considered “mixed” information, as it is conveyed through recognized media and therefore written, but its quality is often very variable and often subject to “manipulation”. We must also be aware that information from social networks and the echo chamber that these create in fact only affects the individuals who use these networks. Generally, we say that “significant” information obtained about societies and individuals is fairly rare, but one should distrust gossip and other acts and ideas harmful to the reputation of a society or an individual.

If this typology is created to classify types of information in general, we must also consider the fact that sources of information evolve very quickly. A few years ago, most information was accessible in written form (electronic or otherwise). But now, information is broadcast by different media: more and more by voice (discourse, teaching) in the form of photos or videos. Videos are used more and more. For example, to obtain a fast but general and realistic picture of a particular domain, we can proceed as follows: search on the Internet for one or two individuals who are experts in this domain, then search on YouTube to see if they have presented any few-minute clips on the subject in question. Example: soft power or influence. We seek an expert in this domain, find Joseph Nye, then look on YouTube for Joseph Nye’s presentations. We can obtain a series of presentations ranging from one hour to a few minutes in length and which cover the subject.

4.3. Information research

The aim here is not to tackle the question of databases in detail, whether they are commercial or free, but to envisage two specific cases as practice questions.

We examine a series of references taken for example from a large database (patents, Chemical Abstracts, Medline, etc.). These are distributed according to their degree of knowledge (trivial, i.e. everyone knows it, or it is moderately well-known, or background noise and low signals). This first differentiation is also linked to the quality of the individuals (degree of knowledge) seeking information. This is also why in economic intelligence or in monitoring technological system developments [QUA 99] the quality of the individual(s) responsible for collecting the information is crucial. It can also be noted that, depending on the sources of information or the subject tackled, volumes of trivial information, moderately interesting information or unusual information will vary. For example, the database of Chemical Abstracts covers a very broad spectrum of journals, patents, reports, theses, etc. on chemistry, which means that the volumes of information available will be broader than in a narrower database that would only consider work published in scientific reviews and, for example, selected at the outset for their impact factor.

Finally, a third parameter is to be considered when seeking information. This is the age of the information. In fact, outdated information will only have little value for action (apart from information on physical data that does not change over time, but this is very rarely the case in economic intelligence). However, recent or very recent information will be especially useful. Very recent but trivial information may be useful, but it should generate a very quick, almost immediate reaction from the business, as normally everyone, including competitors, know it.

4.4. Research practices: reductionist, holistic

In the previous approach, we process significant volumes of information, often hundreds or indeed thousands of units. This creates a distinction in the way we approach enquiries using information systems.

4.4.1. The reductionist approach

This is the most widespread approach to enquiries. We will try using key words, dates, codes, thesauruses, names of individuals or societies, etc. to obtain a limited number of references that best answer the question asked. One can even proceed by repeated iterations to lead to a desired result. This is for example very useful when making enquiries for data on the Web with a search engine such as Google. In this case, it is necessary to bring interesting data “to the surface”, to use all available functions, such as searches for chains of characters (an exact phrase for example), or a type of document (docx, ppt, pdf, xls, etc.), or dates (last week, month, year), or possibly the type of domain (.edu, .gov or .gouv, .org, .com) or country of provenance (.fr, .us, etc.). We will not go into detail on using Google functions. The reader can refer to the work of Henri Dou [DOU 17]: Information Bits & Tips for CI, which shows the most useful functions in the domain of documentary research on the Internet. In this approach, it only remains for the user to read the results and summarize them. But, if the focus is very precise, which is useful in some cases, it will deprive the user of a broader vision of their subject, and the ins and outs of it. It is in this sense that this approach is reductionist. Only using this approach will deprive the user of the knowledge needed to develop their action, but also, what is more important, of the knowledge needed to apply their knowledge in related domains that provide differentiation. This aspect is very important for businesses that often see their core activity drop due to “wear over time” and should therefore replace or modify it to access new customers, or when large sub-contractors for example wish to evolve into more intelligent, indeed strategic sub-contractors (in partnership with the customer) [DAV 94, ZIN 17]. This is also the case in transfer centers, some of which revisit their activities, as Pierette Bergeron describes:

“In 1983 the German foundation Steinbeis adopted a new approach, with transfer centers. It moved from the role of technology provider to a holistic approach to solving problems.” [BER 00]

4.4.2. The holistic approach

This investigative approach is exactly the reverse of the previous one. Rather than searching for the most relevant information, it will search for wide-ranging information, with fluid perimeters, which broadly cover the subject tackled. It is evident that proceeding in this way forms a large opening into all aspects of the subject (this opening is limited according to the specifics of the chosen database; in fact, a biology database will provide a comprehensive opening onto the biological aspects of this subject alone). However, this holistic approach, imposes a constraint although it is particularly good in the context of a search for strategic information and in particular weak signals enabling a differentiation between competitors. In fact, it is not a question of reading hundreds of documents, or even of grouping them by affinity or making sophisticated selections of them. It will be absolutely necessary to use a technical aid to analyze all the documents using statistical algorithms making it possible to make selections, groupings, matrices (who makes what for example), networks (business networks, researchers, technologies). This analysis, which in fact means using bibliometrics for documentary ends, makes it possible to sort information from a large corpus and at the user’s discretion, to regroup these, to make various types of correlation to detect domains that would potentially interest the user as well as information that should be read and assimilated. Moreover, these general processes will lead to a fairly complete knowledge of the subject and so to the chance to develop competencies in diverse domains. In this chapter, we will mainly tackle bibliographical references, but one can also, from codes or thesauruses, create networks providing a holistic view of a subject [LIU 13].

4.4.3. Holistic approach and meta-information or metadata

The holistic approach, during analysis, will often lead to the production of metadata that will be used to obtain, by comparing this data, new information that is almost undetectable or unobtainable by manual processing. The word metadata was used for the first time in 1969 [GRE 05] and introduced into literature in 1973. To familiarize the reader with this approach, we will briefly define what metadata is, based on the work of Kathleen Burnett, Kwong Bur Ng and Soyeon Park:

“From my understanding of what metadata is, metadata is simply defined as ‘data about data’. And to a certain extent and depending on the perspective which you define what metadata is, ‘data about data’ is a legitimate and accurate definition. Looking at the various definitions of metadata we can define metadata as ‘structured data about data’ whereas NISO Press, 2004 describes metadata as ‘data about data or information about information’”1 [BUR 99].

One of the first times the holistic approach to information and the creation of metadata was used was in geography. The work of Moore, Sims and Blackwell is particularly relevant at this level [MOO 01]. It is in this way that “in the early to mid 19th Century, the idealist philosopher Georg Hegel used teleology (the notion of an overall purpose – devised by the early Greeks) to project thinking toward a comprehension of the whole (i.e. the infinite). Similarly, the classical German geographer Carl Ritter believed that the natural and social spheres of existence cannot be treated in isolation as they both affect each other”.

Here we find a modern aspect of economic intelligence, which should now consider the “social” and “culture” in its analysis. An example of metadata in geography is characterization of a site, which may be involved with tourism, sediment formation, fauna and flora, etc. If the data are merely site co-ordinates, the metadata will concern its particularities. Authors have demonstrated the connections that exist between data, action and metadata. This all corresponds to the creation of specific knowledge (in our case “for action”).

In bibliometric processing we will find large sets of references of these diverse particularities. Or indeed, according to Benetts, Wood-Harper and Mills:

“Information systems are increasingly directed towards providing an overall, holistic vision of the subjects tackled.” [BEN 00]

The link between economic intelligence and a holistic approach has been developed in a doctoral thesis by Audrey Naidoo [NAI 03] in which “in order to fully understand the need for competitive intelligence within organizations, one has to create a clear picture of the business environment and the forces that influence it. The problems facing business today demand a turn to integrated, holistic thinking”. It is therefore clear that currently, the global trend in information research is moving toward a holistic vision of the subject whether it is in the domains of the Web [WAN 00] of culture [GAL 05] or the teaching of information research [RUT 08]. Another type of information can be considered as a holistic approach making it possible for example to recognize needs better. This approach was developed recently in Norway for bioeconomics:

“A holistic approach: to do this, over a period of three years (2015–2018), researchers from the Norwegian center for rural research (which is leading the project), SINTEF, Nibio, NTNU and Norut, as well as a number of international research institutes, will work on eleven working modules and so cover most aspects of the transition to a bioeconomy. The key element of this project is an enquiry, now underway, involving 1,500 businesses in the sectors of agriculture, forestry, fishing, industry and the biosciences, to better understand their vision of the future. What are they now using their resources for, and where do they foresee opportunities for change in theirsector?” [FRA 16].

4.5. On scientific journals

The classical vector for sharing knowledge was and still is scientific publication in specialist journals. Publication in these journals is controlled by editors, who have editorial policies. These are linked to their readership, to the journal’s speciality, to the language of publication and of course to subscription costs (it is not always free) or the sales price of a scientific publication’s “full text”. This editorial policy has led leading editors as well as different databases (for example INIST [CAT 17]2 at CNRS), to make databases available to the public (free from the editors’ perspective, for summaries of publications in their journals) and paid-for databases accessible via different servers such as Dialog [DIA 17], STN [STN 17], Questel Orbit [QUE 17], etc. or different portals such as CNKI [CNK 17] in China. This diffusion via these supports generally provides access to a summary of publications, but access to their whole texts requires payment, between US$ 15 and 40 on average. Libraries, in some cases, have subscriptions to scientific journals which makes it possible to access all their publications, but it is clear that the multiplication of scientific journals on the one hand and the ever-growing cost of subscriptions on the other is creating budgeting problems.

Large databases, such as Chemical Abstracts [CAS 17], Medline, Biosis, Inspec, Compendex, etc. have been created to provide potential readers with a summary (indexed to varying degrees) of all the work published in a domain. For example, a database such as Chemical Abstracts [ACS 17] selects a number of sources on activities linked to chemistry (this is the database’s coverage), then for all these sources, which are often written in different languages, it provides an English translation and English-language indexing of the publications that appear in them. The indexing may be relatively inconsistent, from just a few key words to the chemical structure of molecules. Those “abstracts” that appear as a paper edition are now accessible in electronic form via servers that, using data entered by the producer (for example Chemical Abstracts), process this electronically to enable it to be consulted online.

Since the 1970s, this dissemination system has led to English language publications being preferred, both because most editors are English speakers, but also because English has become the common language of science. Moreover, systems for evaluating researchers have led research bodies to establish different criteria, dominated by the number and quality of publications. From these data, different bibliometrics usages make it possible to create the indexes used for evaluation. This practice, which is often misguided (La fièvre de l’évaluation de la recherche [GIN 08]) (the fever of research evaluation) also determines the journal’s impact. This impact is representative of the likelihood of an article published in a given journal being cited by other authors. This introduces three very significant biases that are not often considered by evaluators: the number of researchers present in the discipline (which potentially leads to more citations), the system of citations through “cronyism” often by a group of four authors who cite each other (citations via two or three authors can be detected more easily), some journals, although they may be extremely useful, are aimed at a readership that produces few or no scientific articles and so the journal has very few citations. This system of dissemination has thus brought to the fore in many disciplines a few journals that are considered internationally as the ultimate in publishing. Articles are selected with care and their quality is certain. But what about the rest? In fact, these high-quality journals are very few and only a small number of scientists have access to them. Indeed, science and scientific advances rely on a pyramid to which each researcher provides a contribution. Another point should also be considered: when a researcher publishes their work in a journal, they usually sign away all the publishing rights to their work to the journal’s editor and only retain intellectual ownership of the work. If we consider that many journals are not free, we then have a paradox: the researcher will pay for their work to be published (either directly or through the purchase of reprints) and at the same time, they will be deprived of publishing rights over their scientific production.

As we have just described, this system has existed since the 1950s. But, if in the previous years the major upheaval was access to databases via fast networks such as Transpac [WIK 18a] in France, this situation is changing more and more rapidly with the development of information and communication technologies. In fact, the arrival of the Internet has made access to databases simpler, by promoting the development of simple query interfaces enabling “non-experts” to work with these databases. But although access has become simpler, there has not been any influence on costs. In addition, electronic publishing makes it possible to create books at low cost without going through traditional editors. For example, the Amazon Kindle format [WIK 18b] can be used by individuals to publish their work for free. It will be read on tablets, so the cost of accessing these books remains low (on the order of €10 or often even less). If we remember that an author loses publishing rights when they publish their work through a traditional editor, we see that the impact of new technologies (Open Access for example) should, eventually, profoundly change publishing mechanisms.

Other, different aspects should also be considered: the costs of publishing and accessing information, the barrier of the publication language, a researcher’s reputation.

For around eight years, we have been witnessing the development of a very large number of scientific journals that are mostly published online and indexed in very diverse databases. These journals, which often have attractive titles referring to English-speaking countries, charge a sum on the order of US$80 to 400 publication. The problem is an economic one: many of these journals exist for financial gain. In fact, located for the most part in countries where labor costs are low, they will be a significant source of revenue for the editors, since all the work is carried out online the overheads are low and thus the profits are substantial. This search for profit then leads to the publication of work that is either plagiarized, of no interest, or at the worst a joke. Recently, a completely false publication was sent to more than 300 journals. More than half accepted it without corrections or with only minor corrections. It should be noted that among the journals that accepted the work, a good number featured in the Directory of Open Acesss (DOAJ), which aims to list open access journal of good quality. This gave rise to the appearance of a list of “predatory publishers” on the one hand, and also a relatively official site validating the quality of these journals using diverse criteria [BEA 15]. Among the criteria retained to characterize journals published by predatory editors, we can cite:

“A predatory publisher may:

- – re-publish papers already published in other venues/outlets without providing appropriate credits;

- – use boastful language claiming to be a ‘leading publisher’ even though the publisher may only be a startup or a novice organization;

- – operate in a Western country chiefly for the purpose of functioning as a vanity press for scholars in a developing country (for example utilizing a maildrop address or PO box address in the United States, while actually operating from a developing country);

- – provide minimal or no copyediting or proofreading of submissions;

- – publish papers that are not academic at all, for example essays by laypeople, polemical editorials, or obvious pseudo-science;

- – have a ‘contact us’ page that only includes a web form or an email address, and the publisher hides or does not reveal its location”.

This situation is quite worrying, as it reduces the credibility of all open access journals, which make access to published works accessible to a greater number. Currently, the open archive HAL [ARC 17] makes different scientific works available; researchers make these free to access in the open archive:

“The multidisciplinary open archive HAL, is intended for depositing and publishing scientific articles at research level, published or not, as well as theses, from French or international teaching and research establishments or from public or private laboratories”.

In France, a recent law states that if at least half the funding for research came from public funds, the work, even if it has been published, can be made available in this open archive six months after publication [REP 15], even when the author has granted exclusive rights to the publisher, but this only involves the text sent to the editor for publication and not the final publication that appears in the journal.

The article the law affects is this: article 17, which creates a new article L. 533–4 in chapter III of title III of book V of the Research Code, relates to access to the results of public research.

The academic world produces a considerable amount of information, in the form of scientific publications and data of all kinds. Access to this information and its re-use is a challenge which is simultaneously scientific (sharing knowledge and bringing knowledge to light, the reproducibility of research, interdisciplinary research and stimulating collaboration), economic (opportunities for economy of knowledge and innovation, especially for SMEs, rationalizing the means devoted to research, the changing cost to libraries of subscribing to journals), social and civil (civil participation in research, popular science education, etc.).

Despite the possibilities opened up by digital publishing, access to information is not as easy as we might like. While it is estimated that the quantity of data generated by research is increasing by 30% each year, nearly 80% of the data generated over the last 20 years has been lost for lack of coordinated safeguarding policies. Beside these issues there appears a new risk of this data being stolen, especially by scientific editors who constantly ask for the sale of permission over data integrated into or linked to the research publications they edit.

In this context, article 17 aims to promote the free publication of the results of public research, in accordance both with the recommendations of the European Commission (from July 17th, 2012) on the access to and the preservation of scientific information, and guidelines of the European research framework program Horizon 2020 (2014–2020).

When it comes to access to scientific publications, the article retains the balanced approach favored by Germany, which has anticipated since January 1st, 2014 that, without prejudicing the copyright holder’s rights, the researcher will have “secondary rights” (“Zweitverwertungsrecht”) over their own publications.

The first part of the law anticipates that publications resulting from research activity relying mainly on public funds can be made freely and publically accessible online by their authors, even when the author has given exclusive publication rights to the publisher for scientific work at the end of a maximum period of six months after initial publication. The gap will be 12 months for work in the human and social sciences, where the time for return on investment for publishers is longer. Re-use is free, unless it is published for commercial ends, which could prejudice the publisher. Availability extends to a final version of the text sent by the author to the editor before publication, as well as the protected research data linked to the publication.

The second and third parts of the law aim to promote publication of research data, while still recognizing its essential contribution to the domain of shared knowledge. The second part specifies that the re-use of data from research activities financed mainly from public funds is free, so long as these data are not protected by a specific law, such as an intellectual property law, and so long as they have been made public by the researcher or research body. The third part indicates that the re-use of data cannot be restricted by contract when a piece of written scientific work with which the data are linked is published, when the work has been produced in the context of research financed mainly from public funds.

The growth in the number of researchers in scientific production, but also due to the race for publications (in some countries, researchers or teacher-researchers are asked to publish something every one or two years for example) leads to a “block” if only “quality” and English-language publications are considered. This blockage is due to the fact that the costs borne by the publisher are too high, which then limits the number of articles published. A number of publishers find themselves trapped in this situation, the problem then being to sort the good articles from the bad. This also creates a problem for who referees the work. In fact, in most cases, reviewers review articles for free (this is important in some subjects) and so cannot spend enough time examining the works shown to them. It is true that in return, this gives them the earliest results before they are published.

Here, we see the limits of the exercise and the biases that can result from it when there is competition between several research teams. In this regard, we can mention the heated debate that took place between research teams led by Professors Luc Montagnier (France) and Robert Gallo (United States) on the discovery of the AIDS virus [MOI 09].

Beyond competitions between research teams, the language barrier is significant, and at two levels: translation into English and considering a journal in a language other than English for indexing purposes. Being translated into English or personally mastering the language is a substantial barrier to publishing in some journals. In fact, a translation certificate is often requested before the work is published and reviewed. This then leads to a kind of “double punishment” for those who cannot publish in English or afford the funding to do so. It also opens the way for English co-authors of convenience, who are listed as co-authors of the paper without really contributing to it, which makes publishing much easier.

This trend toward English being used as the basis for publication leads to works published in regional reviews being overlooked where work is published in a country’s own language. In fact, two aspects should be considered: indexing and translating the work have a significant cost for the producer of a database and on the other hand, these local journals will never have a high citation index and so, even if they are high quality, they will remain partly ignored. However, for those who know how to use them, they are often a source of interesting ideas that can be used in later work. For example, we can list the Chinese CNKI portal (China National Knowledge Infrastructure) that gives access to a number of local works. It might also be noted that the great effort made by China in the field of scientific publishing in Chinese-language media will have the opposite effect, creating a linguistic barrier that works against us. The CNKI portal [CNK 17] “is an important national information construction project directed by the University of Tsinghua and supported by the PRC minister of education, the PRC minister of sciences, the propaganda department of the Chinese Communist Party and the general administration for the press and publication. This was project was first launched in 1996 by the University of Tsinghua and the Tsinghua Tongfang Company. The first database was the China Academic Journals Full-text Database (CD version), which quickly became popular in China, especially in university libraries. In 1999, CNKI began to develop online databases. Until now, CNKI formed a complete system of resources integrated with Chinese information resources, including reviews, doctoral theses, master theses, conference proceedings, journals, annuals, statistical annuals, e-books, patents, norms and so forth. Ten publication centers and service management centers (CNKI) have been set up in Peking, North America, Japan, North Korea, Taiwan and Hong Kong. CNKI is generally used by universities, research institutes, governments, think tanks, businesses, hospitals and public libraries across the entire world”3.

The initial CNKI home page is shown in the figure below. For those who might be interested in consulting this portal, the University of Leeds has created a quick guide [UOL 17] accessible via the Internet. We note that to use CNKI, it is necessary to enter certain terms or key words in simplified Chinese. This is done by using Google translate, with which we have been entirely happy.

Figure 4.6. Home page and description of CNKI. For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/dou/strategic2.zip

Another example where it will be important to consider the language used in a search is the following: if we search for works on sugar from some palm trees (this sugar has special nutritional properties), we can search in English using Google Scholar: with “palm sugar”, we obtain a number of results. However, if we remember that one of the foremost producers is Indonesia, this leads to us searching, still in Google Scholar (which is actually a multilingual database) with: “gula aren”4 to find interesting work by practitioners. But these are written in Indonesian. This reflects the difficulty linked to language when a database covering multi-lingual work is used:

- – Google Scholar, limited to “since 2014” “palm sugar” AND diabetes, returns 228 results (January 15th, 2018);

- – Google Scholar, limited to “since 2014” “gula aren” AND diabetes, returns 89 results (January 15th, 2018).

The level of coverage for both results is very low.

4.6. Conclusion

Over the course of this chapter, we have seen the potential offered by a search for information as well as the biases to be avoided when choosing sources. We have also emphasized the fact that a good knowledge of the subject is vital to making good-quality queries whether at reductionist or holistic level. This leads to an emphasis on the means of seeking information as soon as an economic intelligence system has been put in place. As success requires a general overview of the subject to be addressed, the work should be carried out in direct association with a subject specialist and with someone who knows how to access the most relevant sources of information on the one hand, and on the other hand, who knows how to process this information to provide the most relevant indicators for the subject addressed. In this context, we can reach a two-fold, or indeed a three-fold competency by integrating, over the years, the global component “information and processing” in the context of activities [DOU 08]. Moreover, since the time factor is important, research and analysis should be updated regularly according to the evolution of works linked to the subject over time.

4.7. References

[ACS 17] THE AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY, 2017, available at: http://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/cas.html.

[ARC 17] ARCHIVE OUVERTE HAL, 2017, website available at: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/.

[BEA 15] BEALL J., Criteria for determining predatory open-access publishers, Online article, 2015, available at: https://scholarlyoa.files.wordpress.com/2012/11/criteria-2012-2.pdf.

[BEN 00] BENNETTS P.-D., WOOD-HARPER A.-T., MILLS S., “A holistic approach to the management of information systems development: a view using a soft systems approach and multiple viewpoints”, Systemic Practice and Action Research, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 189–205, 2000.

[BER 00] BERGERON P., Veille stratégique et PME. Comparaison des politiques gouvernementales et de soutien, Presses de l’université du Québec, Quebec City, pp. 102–103, 2000.

[BUR 99] BURNETT K., KWONG BOR N., SOYEON P., “A comparison of the two traditions of metadata development”, Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, vol. 50, no. 13, 1999, available at: http://www.sims.monash.edu.au/subjects/ims2603/resources/week10/10.2.pdf.

[CAS 17] CAS (A DIVISION OF THE AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY), Website, 2017, available at: https://www.cas.org/.

[CAT 17] CAT.INIST, Journal, Website, 2017, available at: http://cat.inist.fr/.

[CNK 17] CNKI, Website, 2017, available at: http://en.cnki.com.cn/.

[DAT 17] COMMIT EE ON DATA OF THE INTERNATIONAL COUNCIL FOR SCIENCE, Website, 2017, available at: http://www.codata.org/.

[DAV 94] D’AVENI R.A., Hyper-Competition, Managing the Dynamics of Strategic Maneuvering, pp. 176–177, Free Press, New York, 1994.

[DIA 17] DIALOG BLUESHEETS, 2017, available at: http://library.dialog.com/bluesheets/.

[DOA 17] DOAJ (DIRECTORY OF OPEN ACCESS JOURNALS), Website, 2017, available at: https://doaj.org/.

[DOU 08] DOU H., “Des sciences dures à la veille technologique et à l’intelligence économique”, in J.-P. BERNAT (ed.), L’intelligence économique : co-construction et émergence d’une discipline via un réseau humain, Hermès-Lavoisier, Cachan, 2008.

[DOU 17] DOU H., Information Bits and Tips about Competitive Intelligence, Kindle Amazon, 2017.

[FAC 17] FACTURATION DIALOG, 2017, available at: http://library.dialog.com/bluesheets/html/bl0002.html.

[FRA 16] FRANCE DIPLOMATIE, “Projet Biosmart : la Norvège recherche sa bioéconomie”, March 16, 2016, available at: http://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/fr/politique-etrangere-de-la-france/diplomatie-scientifique/veille-scientifique-et-technologique/norvege/article/projet-biosmart-la-norvege-recherche-sa-bioeconomie.

[GAL 05] GALLIVAN M., SRITE M., “Information technology and culture: identifying fragmentary and holistic perspectives of culture”, Information and Organization, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 295–338, 2005, available at: http://www.cis.gsu.edu/mgallivan/journal/Gallivan_and_Srite_Info_and_Organization_2005.pdf.

[GIN 08] GINGRAS Y., “La fièvre de l’évaluation de la recherche : du mauvais usage de faux indicateurs”, Bulletin de méthodologie sociologique, vol. 100, no. 1, pp. 41–44, 2008, available at: https://bms.revues.org/3313.

[GRE 05] GREENBERG J., “Understanding metadata and metadata schemes”, Cataloging & Classification Quarterly, vol. 40, nos 3–4, pp. 17–36, 2005, available at: http://www.columbia.edu/cu/libraries/inside/units/bibcontrol/osmc/greenberg.pdf.

[ISD 17] ISDM (INFORMATION SCIENCE FOR DECISION MAKING), Website, 2017, available at: http://isdm.univ-tln.fr/isdm.html.

[LIU 13] LIU P., BOUTIN E., DUVERNAY D. et al., “Les Thésaurus comme outils de repérage de la diversité culturelle dans les pratiques d’une discipline. Approche expérimentale dans le champ de l’intelligence économique”, HAL, 2013, available at: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/52781874.pdf.

[MOI 09] MOINET N., Liberté, compétitivité, sécurité : la communication scientifique entre coopération et concurrence, Sécurité Globale, Éditions Eska, Paris, 2009.

[MOO 01] MOORE A., JONES A., SIMS P. et al., “Integrated coastal zone management’s holistic agency: an ontology of geography and GeoComputation”, The 13th Annual Colloquium of the Spatial Information Research Centre, Dunedin, New Zealand, November 26–28, 2001, available at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Antoni_Moore/publication/228397767_Integrated_Coastal_Zone_Management’s_Holistic_Agency_An_Ontology_of_Geography_and_GeoComputation/links/54adb6340cf2213c5fe41827.pdf.

[NAI 03] NAIDOO A., The impact of competitive intelligence practices on strategic decision-making, PhD thesis, Université de Natal Durban, 2003, available at: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.833.8758&rep=rep1&type=pdf.

[POW 95] POWELL T.-W., “The information metabolism”, Competitive Intelligence Review, vol. 4, pp. 41–45, 1995.

[QUA 99] QUAZZOTTI S., DUBOIS C., DOU H., Veille technologique. Guide des bonnes pratiques en PME/PMI, Guide for the European Commission, 1999.

[QUE 17] QUESTEL ORBIT, Website, 2017, available at: http://www.questel.com/index.php/en/support/coverage.

[REP 15] ASSEMBLÉE NATIONALE, Projet de loi pour une République numérique, no. 3318, 2015, available at: http://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/14/projets/pl3318.asp.

[RIL 04] RILEY J., Understanding metadata: what is metadata, and what is it for?: A Primer, Guide, National Information Standards Organization, Baltimore, 2004.

[RUT 08] RUTHVEN I., ELSWEILER D., NICOL E., Designing for users: an holistic approach to teaching information retrieval, Workshop, 2008, available at: https://epub.uni-regensburg.de/22683/1/ruthven2008_teaching.pdf.

[STN 17] STN, Website, 2017, available at: http://www.cas.org/products/stn/dbss.

[UOL 17] UNIVERSITY OF LEEDS, THE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY, CNKI: China Academic Journals: quick start guide, 2017, available at: https://library.leeds.ac.uk/dowmload/downloads/id/330/cnki_china_academic_journals_quick_start_guide.pdf.

[WAN 00] WANG P., HAWK W.-B., TENOPIR C., “Users’ interaction with World Wide Web resources: an exploratory study using a holistic approach”, Information Processing & Management, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 229–251, 2000.

[WIK 19a] WIKIPEDIA, “Transpac”, 2019, available at: http://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transpac.

[WIK 19b] WIKIPEDIA, “Amazon Kindle”, 2019, available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amazon_Kindle.

[ZIN 17] ZINS BEAUCHESNE ET ASSOCIÉS, “Comment innover lorsqu’on est sous-traitant”, Dailymotion, 2017, available at: http://www.dailymotion.com/video/xfsm29.