Chapter 3: Investing for super beginners

"The big secret in life is that there is no big secret. Whatever your goal, you can get there if you’re willing to work."

Oprah Winfrey, TV personality, billionaire and philanthropist

Once upon a time there was a young woman named Jane. She had never heard the word superannuation before so she asked her mum what the word meant. Her mum told her that superannuation is when money is put aside, like deferring some of your pay, for a better lifestyle later on in life. Her mum said if you have a job you can expect your employer to pay money to a special account run by a superannuation fund. You can even make your own deposits into the superannuation account if you want more money for your life later on.

Jane went away and thought about this thing called superannuation, and wondered what would happen to her own superannuation for the next 20 or 30 years, until she needed it later on in her life. She asked her mum. Her mother released a deep sigh, realising the importance of this moment, and put the kettle on. She told her daughter to take a seat and promised to start from the very beginning. And so she began the story of how a superannuation account was created, and how the money in Jane’s super account was transformed into investments ...

Okay, the brief story above is the beginning of an unrealistic fairy tale, but in an ideal world, we would be taught about finances, investing and superannuation by our parents or by schools, like we’re taught about reading, writing, manners, the facts of life and possibly even the merits of common sense. The reality is that most of us were never given the opportunity to learn about investing. If you’re lucky enough to know a lot about investing then you either had parents who were investors, or you taught yourself about investing.

Although this book is not strictly an investment book, a superannuation fund invests money on behalf of its members, which means how you and your super fund invest is an important contributor to your retirement wealth.

This chapter fills in some of the gaps for those women who have never been exposed to investing, and provides a refresher for those who have forgotten the difference between saving and investing, or forgotten the importance of maintaining the purchasing power of their hard-earned money.

You can read this chapter in one sitting, or treat it as a reference to dip in and out of while reading the rest of the book. If you are an experienced investor, then you could scan this chapter and move on to chapter 4, or you can linger over the fascinating examples illustrating the delights of compound earnings. Go on, be tempted.

For a more detailed resource on investing, I suggest you check out my book, You Don’t Have to Be Rich to Become Wealthy: The Baby Boomers Investment Bible (Wrightbooks, 2007), which was co-authored with Ian Murdoch and Jamie Nemtsas. Despite the book title, you don’t have to be a baby boomer to benefit from the book.

Drumroll — the key elements of wealth generation

If you scan the financial pages of any newspaper you’re likely to find advertisements promoting money-making schemes. Many of these schemes require you to undertake expensive courses and often involve high-risk ;strategies.

Unless you’re planning to be a full-time professional investor who buys and sells investments regularly, the basic principles of investing and creating wealth are not complex. The key elements to accumulating wealth, consistently over time, are:

• Don’t spend more than you earn, unless you are borrowing to invest in quality assets.

• Have some type of plan — it doesn’t have to be a formal plan, but you need to have some idea of what you want in the end, and the risks you’re willing to take to get there.

• Invest wisely — understand what you invest in, or what your super fund invests in, and if you’re worried about the possibility of losing money, ensure you spread your savings over different asset classes and different investments.

• Don’t spend your investment earnings, yet! Instead, reinvest your investment earnings and enjoy the benefits of compound earnings.

Saving money is different from investing

Investing means making your money work as hard as you do. Investing also means your money is working for you even when you’re sleeping, or on holidays, or taking time out of the workforce to raise children or to return to study.

The most enticing feature of investing your money (and having your money in a superannuation account means your money is usually being invested by investment experts) is that you have your money working for you, rather than you working for your money.

The concept of saving as opposed to investing can often be confusing. For example, if you have your money in a bank account that pays no interest, then that bank account is not an investment. You may have savings but those savings are not working for you, as an investment would. If, however, the bank pays interest on your bank account balance, then your account can be considered an investment, because the bank account is generating a return in the form of interest. Depending on what level of interest (the return) the bank pays on your account, you may consider it’s a good investment or bad investment.

Compound earnings make you richer

The easiest way to accumulate wealth in a steady fashion is by reinvesting the earnings from your investments. You then earn more interest (or investment earnings) on your interest, which means your investments grow faster over time.

One of the key advantages of superannuation is also seen as one of its key disadvantages. Many people complain that they can’t access their superannuation until they retire, but this rule also means that your super account’s investment earnings are reinvested regularly for a long time. Keeping your investment earnings in your super fund for 10, 20 or 30 years, or even longer, means you’re building a much bigger nest egg for your retirement than you could have achieved if you were able to withdraw your money at any time.

Doubling your money is all about time

Want to double your money? Depending on the risk that you’re willing to take, you can double a one-off investment in four to five years — though it’s more likely that it will take between seven and 10 years, assuming you re-invest your earnings. By reinvesting your investment earnings, your initial investment can then enjoy the magical benefits of compound earnings.

If you’re also willing to make regular contributions to your super account, or other investments, then your investment portfolio will double in value in super-quick time, assuming the investment markets are performing well. You can also lose money when investing. Anyone with a superannuation account can probably recall the negative investment returns (investment losses) suffered by most Australian super fund members during 2008 and 2009. Over the longer term, however, you can expect a typical super account to deliver positive and decent returns.

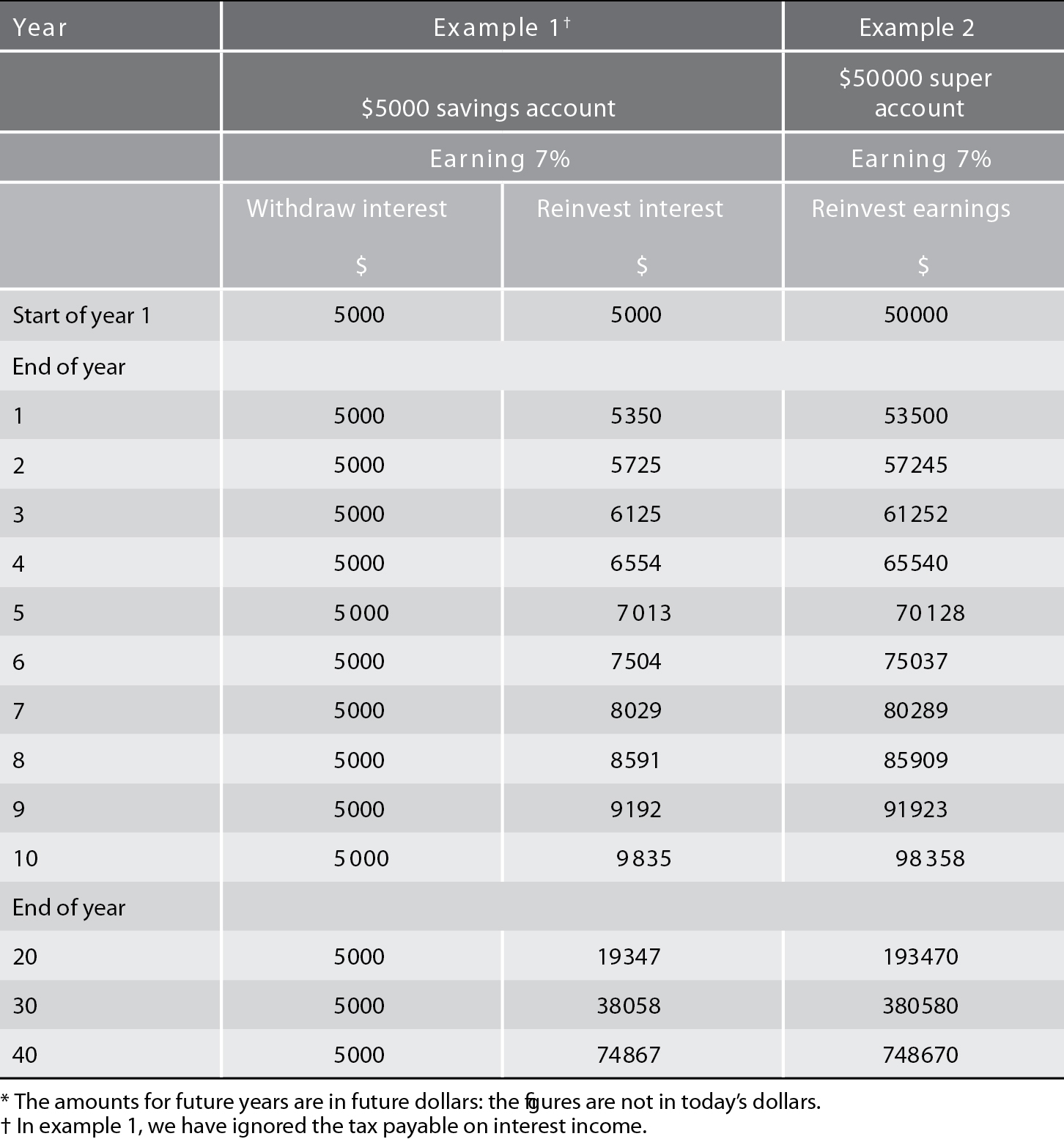

Example 1: double your money

Renee has deposited $5000 in a savings account earning 7 per cent in interest each year, or $350 in interest each year. If Renee leaves her $5000 in the savings account for five years, but chooses to spend her interest each year, she will still have $5000 in her savings account at the end of five years, but she won’t have accumulated any more wealth (see example 1 in table 3.1). In fact, because of inflation (rising prices), her $5000 will buy her less in five years’ time than she can buy with her $5000 today. If, however, Renee reinvested her annual interest, she would have more money at the end of the five years. You might think Renee’s savings account would then total $6750 ($5000 plus five years worth of $350 annual interest). Not so! Renee’s balance after five years of reinvesting interest totals $7013, due to the effects of compound earnings: she has earned interest on her interest. Ignoring tax, if Renee then reinvests her earnings for another five years she can nearly double her original investment from $5000 to $9835 — just under $10 000 (see example 1 in table 3.1).

Example 2: double your super money

Now let’s change the story: assume Renee has $50 000 in a superannuation account and she makes no further contributions to that account for the next 10 years. This scenario is very common for women who take time out of the workforce to raise children. If Renee’s superannuation money is invested in assets that deliver 7 per cent return after fees and taxes, then her super account balance will grow to $98 358 — nearly double her original balance after 10 years (see example 2 in table 3.1), and double again to nearly $200 000 after another 10 years, and double again to nearly $400 000 after another 10 ;years, growing to nearly $750 000 after 40 years — if she still hasn’t withdrawn her retirement savings after 40 years.

Table 3.1: watch Renee’s savings grow*

Aiming for higher return means greater risk

In example 2, I have assumed an annual return on Renee’s superannuation account of 7 per cent after fees and taxes because that is typically the expected long-term return on what is called a balanced investment option. Most Australians have their superannuation money in a balanced investment option, which usually involves a larger portion of shares, property and other higher risk assets, and a smaller portion of cash and lower risk investments, such as fixed-interest investments.

The different categories of investments, such as cash, shares and property, are each known as an asset class. How a super fund divvies up your super money into the different asset classes is known as asset allocation, and most super funds let you choose from different asset allocations, such as conservative, balanced, growth, and high growth or aggressive. Your super fund may give these investment options different names, which can be confusing. (See chapter 10 for an explanation of the investment options offered by super funds and examples of typical asset allocations.)

Although I use an earnings rate of 7 per cent after fees and taxes as the assumed rate of return in the examples discussed in this book, you can choose to invest your super in an asset mix (investment option) that produces returns greater than 7 per cent after fees and taxes over the long term, which means that you usually take on greater risk when investing. Typically, higher risk investment options are called growth, high growth or aggressive growth, and some investment options involve investing in only one asset class, such as an Australian or an international shares option.

The general rule is that the higher the return you aim for, the greater the risk you take. By using the free online calculators referred to throughout this book, you can test a different rate of return, higher or lower than 7 per cent, for your investments if you wish.

If you are willing to accept the occasional negative return (investment loss) in the pursuit of higher returns, then the investment world would describe you as having a medium to high tolerance for risk. If you want to avoid suffering any investment losses, then you would need to consider investments that are lower risk but also deliver lower returns over time. If you fit into the more conservative, risk-averse category, then you’re likely to be described as having a low tolerance for risk.

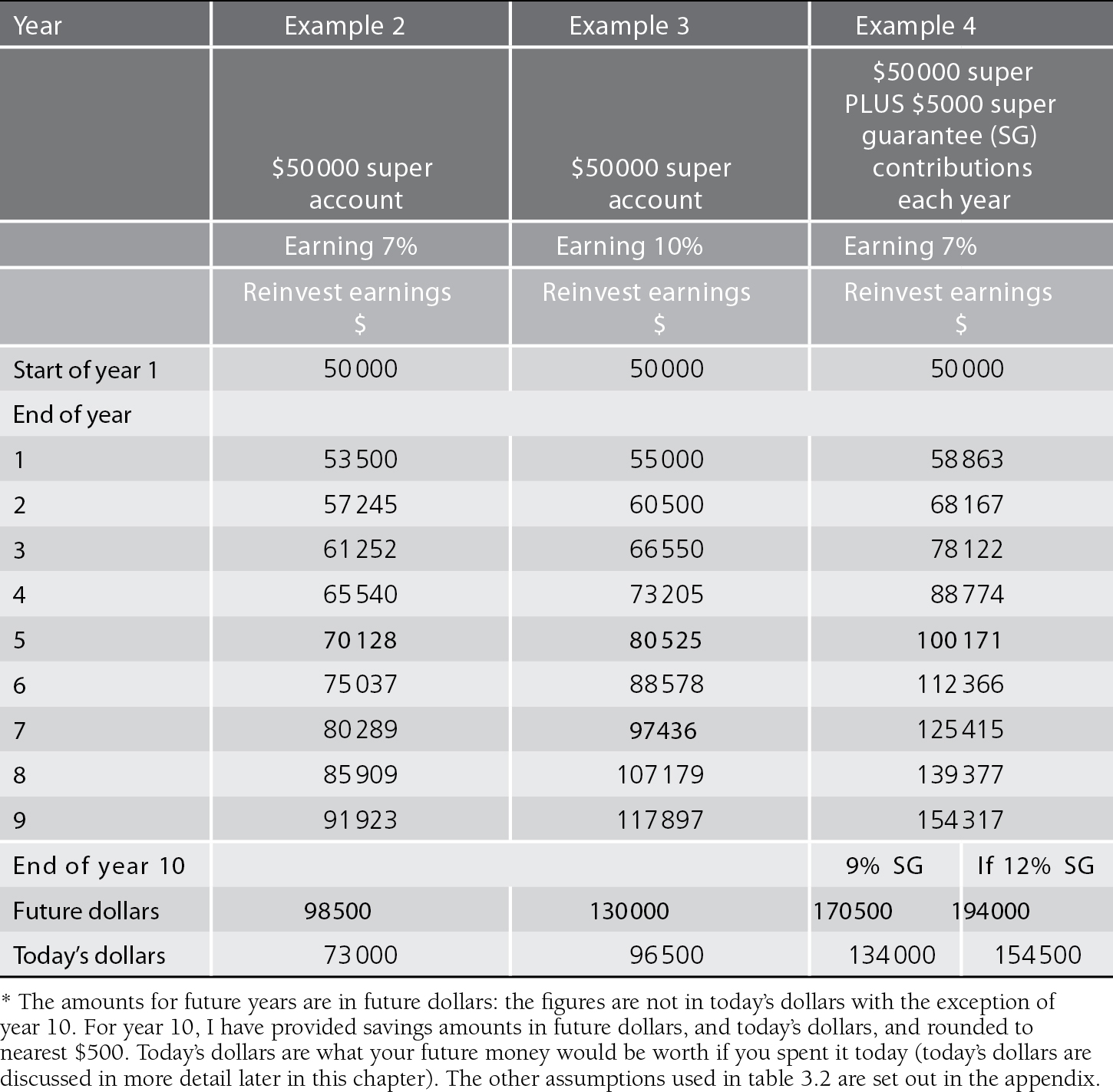

Example 3: higher returns mean faster wealth, but more risk

Renee has decided she has a high tolerance for risk, and wants to aim for an investment return of 10 per cent each year on her superannuation money so it can build more quickly while she isn’t working, even though that means that she takes on the risk of having a bad investment year or two during the next 10 years. Renee has shifted all of her superannuation money into a high growth investment option in her superannuation fund, which means 90 per cent of her super money will be invested in Australian and international shares, property investments and other higher risk investments, and the remaining 10 ;per cent will be invested in cash. Let’s assume that each year, for the next 10 years, the high growth option delivers a 10 per cent return after fees and taxes. If Renee made no additional super contributions, her starting account balance of $50 000 nearly doubles after seven years to $97 000 and reaches $130 000 after 10 years (see example 3 in table 3.2, overleaf ). For Renee, a 3 per cent difference in investment return means a $30 000 difference in her retirement account balance (compare with example 2 in table 3.2).

Example 4: add more money and compounding works faster

Renee has just been offered a job after several years out of the workforce raising children. She is returning to full-time employment tomorrow, which means that her superannuation account balance of $50 000 will benefit from the effects of compound earnings plus a super boost when her employer makes regular compulsory super contributions (in accordance with her employer’s SG obligations). Renee realises that she probably won’t have to take as much risk as she thought she needed to take when investing her super money (see example 3 in table 3.2) because she will now have additional money going into her account regularly, which also enjoys the benefits of compound earnings. She decides to keep her super money in the balanced investment option, which we assume will deliver 7 per cent returns after fees and taxes.

For simplicity, let’s assume Renee’s employer contributes roughly $5000 in compulsory SG contributions for the year, after super contributions tax of 15 ;per cent is deducted ($5895 less 15 per cent tax equals $5011), which means her annual salary is around $65 500. At the end of 10 years, Renee’s super account balance will be $170 500 (see example 4 in table ;3.2).

Table 3.2: watch Renee’s super savings grow faster*

Now that’s not the end of the story, because $170 500 in 10 years’ time is not the same as $170 500 today. In today’s dollars, that $170 500 is worth around $134 000 due to the effect of inflation (assuming annual inflation of 3 per cent).

When the legislation to increase the rate of SG contributions has been passed, Renee’s employer will have to contribute the equivalent of 12 per cent (from July 2019, and between 9.25 and 12 per cent from July 2013) of Renee’s salary (rather than 9 per cent), which means she can expect a slightly larger final balance than what appears in example 4. For reference, I have included the final amounts if Renee received 12 per cent in super guarantee contributions for the same 10-year period, at the bottom of example 4 in table 3.2. In reality, Renee’s super balance will be somewhere between $170 000 and $194 000 because she won’t receive 12 per cent in SG contributions for the full 10-year period.

Now, time for a short break and a cuppa. See you in a few minutes.

Diversification — balancing return with necessary risk

The return (also known as earnings, income or profit) from an investment is only one side of an investment. You also need to think of the risk of an investment — the possibility of losing your money, which many members of super funds experienced during 2008 and 2009. Some investors also count risk as missing out on a higher return on another investment.

Having money in a bank account in Australia is considered a low-risk investment, because you are unlikely to lose money, and an attractive investment for part of a person’s investment portfolio. An investment portfolio is the collection of investments a person may hold. An example of a possible investment portfolio could be, say, three high-interest bank accounts, two investment properties, and shares in 12 Australian companies listed on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX).

If you want a return higher than the interest you can earn on a bank account, then any investment you choose will generally hold greater risk than a bank account. Over time, however, it should also deliver you higher returns. Many investments that deliver higher returns can have a bumpy performance from one year to the next, so you generally expect to hold higher risk assets for five years or more so the strong years outweigh the years of not-so-strong ;performance.

Your super fund also makes investments. Many Australians, and most super funds, expect to invest money in higher risk investments, such as property and shares. Such investments are higher risk because you are investing in businesses or assets that are subject to the ups and downs of economic cycles, and dependent upon the competence of the individuals managing those assets. Over the longer term, property and shares deliver higher returns than cash in a bank, but in some years, property and share investments can lose money.

The challenge is to balance the risk of potentially losing money with the ultimate aim of delivering decent long-term returns. Most investors, including superannuation funds, balance the desire for higher returns with the possibility of losing money, by investing across different asset classes (such as cash, shares and property) and in a variety of assets within these asset classes. This approach to investing is known as diversification. The way you, or your super fund, decide how to spread the risk across different assets is known as asset allocation.

Are you still with me? I’m planning to keep the technical talk to a minimum but bear with me for a few moments longer.

Creating and protecting your wealth for retirement

Why would you, or your super fund, bother having an investment if you could lose your money? Why not just have your money sitting in a bank account that’s safe, even though it pays no interest or pays only low interest?

Leaving your money in a bank account that pays interest (known as a cash investment) is certainly a legitimate option, but there are probably three main reasons for also considering investing your money in other assets:

• Protecting the purchasing power of your money. Inflation, that is, rising prices, can affect the purchasing power of your savings over time. If inflation is running at 4 per cent a year, then your investments need to return at least 4 per cent a year after tax to ensure you protect the real value of your money. An important question to ask is: what can the money you receive in the future buy you in today’s dollars? I explain the concept of today’s dollars later in this section.

• Accumulating wealth. The minimum requirement for any investment plan is to protect the purchasing power of your money. If you want to accumulate wealth, however, the returns you want from your investments over the longer term need to exceed the inflation rate, and exceed any taxes payable on your investment income. I explain the effect of inflation and tax on your superannuation account, and on your life in retirement later in this section.

• Creating a regular income from your investments. Once you accumulate your wealth, you’re likely to want your savings, including your superannuation account, to give you a regular income in retirement. The longer you plan to be retired, the larger the lump sum you need to invest upon retirement. (How much is enough and the type of lump sums you can plan for are discussed in chapter 4.)

Living for today — in today’s dollars

Think back to the dream that you have for your retirement. If you plan to live off, say, $40 000 a year in retirement, I assume you’re talking about what $40 000 a year buys you today, rather than what $40 000 buys you in 10 or 20 ;years’ time. Inflation, that is, rising prices, can affect the purchasing power of your savings over time.

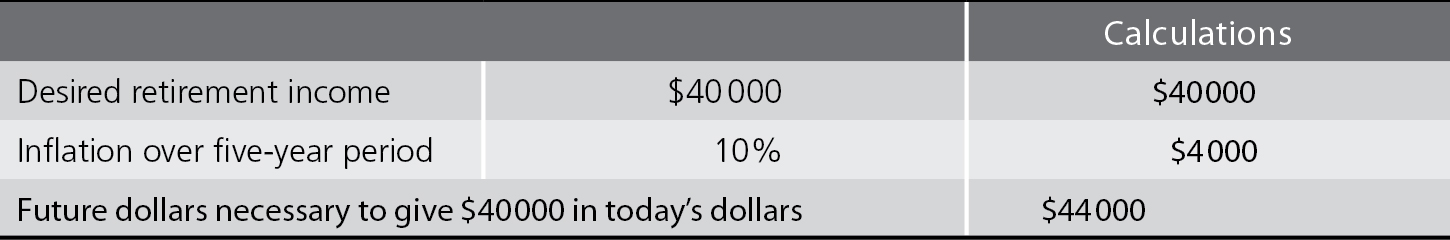

Example 5: let’s talk about today’s dollars

Claire is a part-time teacher, and she owns a property investment. She lives very happily on $40 000 a year, so Claire wants to have a similar lifestyle when she retires. What Claire means is that she wants to live off $40 000 a year in today’s dollars, that is, what $40 000 can buy her today, rather than what $40 000 can buy her at some time in the future. If the cost of living increases by 10 per cent over a five-year period, then in five years’ time it will cost Claire $44 000 to maintain the lifestyle that $40 000 in today’s dollars can buy her (see table 3.3). If inflation was 20 per cent over the five-year period, then Claire would need $48 000 in five years’ time to maintain the lifestyle she has today on $40 000 annual income. The concept of today’s dollars can be confusing so feel free to read example 5 a second or third time.

Table 3.3: today’s dollars in future dollars — what $40 000 today is worth in five years’ time (example 5)

What today’s dollars means for anyone planning for their retirement is that if you want to protect the purchasing power of your money you generally need to invest in assets that produce a return that will at least deliver the same amount as the rate of inflation. (In chapter 4, I highlight the importance of using today’s dollars when planning for your retirement.)

Successful investing means real returns after tax

I have covered a lot of concepts in this chapter, but the key message is this: if you’re able to save money, then you’re well on your way to accumulating wealth. From reading this chapter, you now know that saving your money is not the end of the story. Saving money is a good start, but investing your money means your savings are put to work, and investing is the key to accumulating ;wealth.

You may be thinking: ‘Why is she telling me all this guff — what does this have to do with superannuation, retirement planning, or me?’ Well, accumulating wealth is not just about choosing good investments, or selecting a super fund that chooses good investments. Accumulating wealth for retirement generally means what you can afford to buy with your wealth when you retire. It’s also about how much money you give to the taxman along the way.

I want to introduce two more concepts, and I promise they will be the last for this chapter. The two concepts are:

• real returns

• after-tax returns.

A real return is simply the return you get on an investment after you have deducted the effects of inflation. If your bank account pays 4 per cent interest each year, and inflation (also known as the increase in the Consumer Price Index, or CPI) is increasing at 4 per cent each year, your savings have retained their purchasing power, but they won’t be growing in real terms. If you want your savings and investments to retain their purchasing power over time and grow in real terms, then you will need to ensure that the return on your investments exceeds the rate of inflation.

Example 6 — real returns give you more of today’s dollars

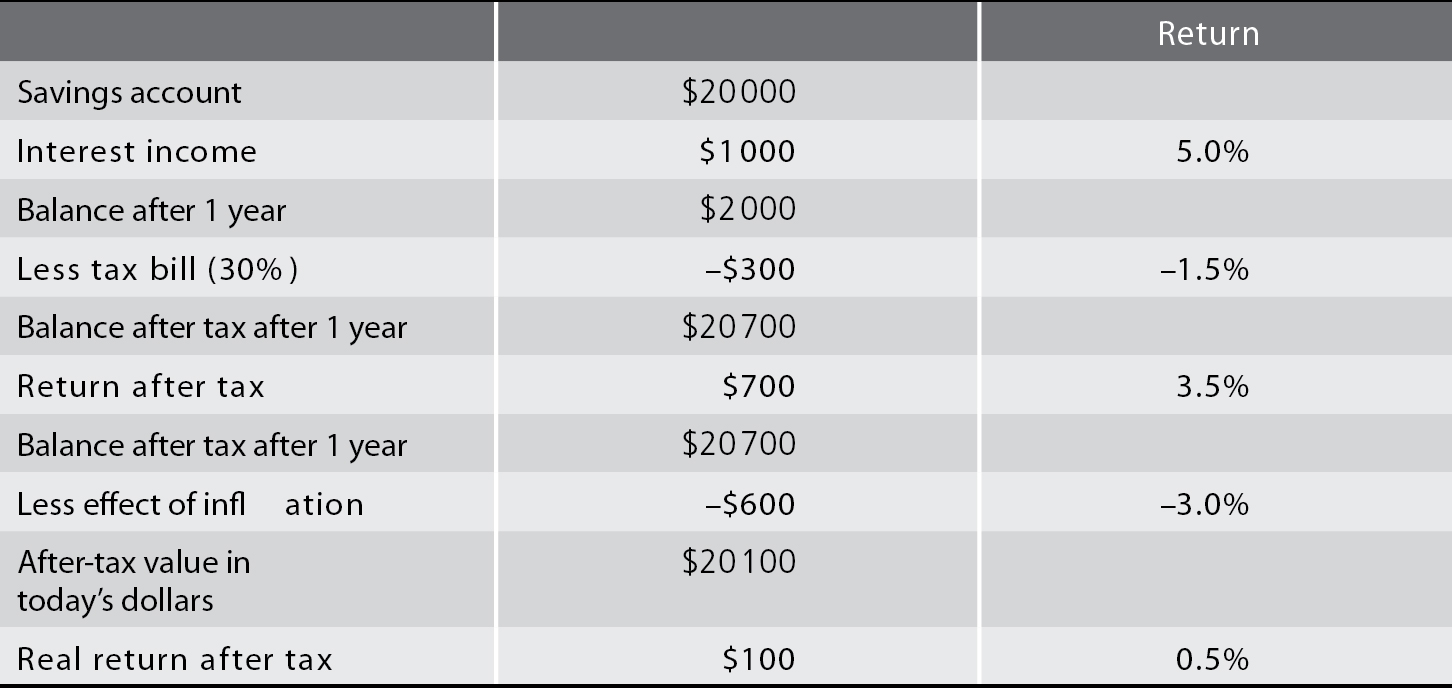

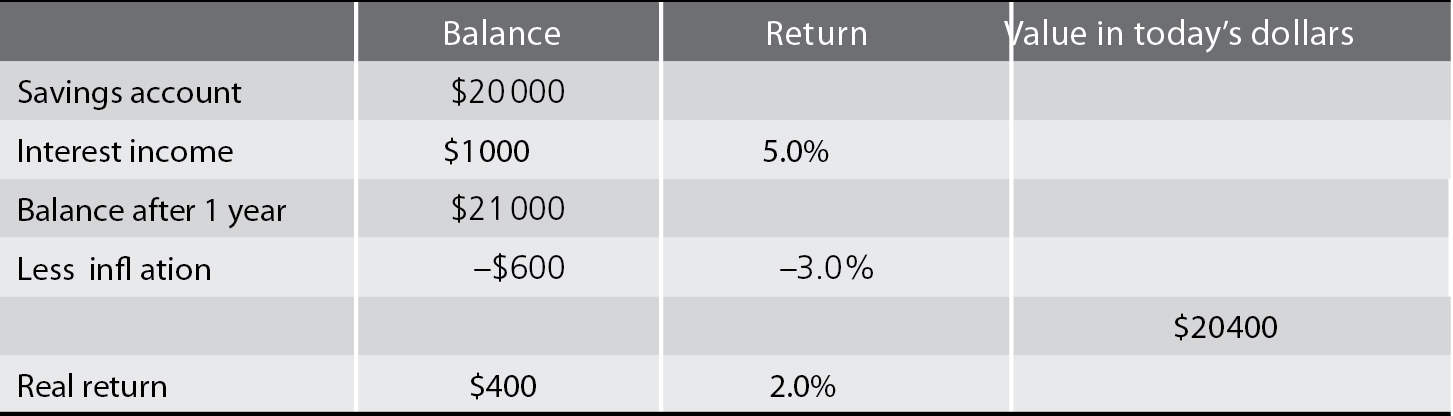

Claire, our friend from example 5, has $20 000 in a high-interest savings account earning 5 per cent a year in interest (see table 3.4). Her income from annual interest on her savings account is $1000, which means Claire’s account balance grows to $21 000 after 12 months. Inflation for the year is 3 per cent, which means Claire’s real return, that is, after taking inflation into account, is 2 per cent (5 minus 3). In dollar terms: $1000 interest less $600 (effect of inflation) equals $400. Although Claire’s savings account has grown to $21 000, her account is worth $20 400 in today’s dollars (rather than $21 000) in 12 months’ time, due to the effect of inflation.

If Claire paid no tax, the good news is that her savings account has maintained its purchasing power, and actually grown in real terms by 2 per cent (see table 3.4). However, like most Australians, it turns out that Claire does indeed pay tax, which reduces her earnings further (see example 7, and table 3.5 on p. 42).

Table 3.4: real return on Claire’s investment (example 6)

Example 7: what matters is real returns after taxes

Claire earns $40 000 a year from her teaching and from her property investment. More precisely, she has taxable income of $40 000, which is the income the tax office recognises for taking its cut in tax. Enjoying this level of income means Claire must pay 30 per cent income tax (for the 2011–12 financial year) on any additional income that she earns, such as interest on her savings account. Her interest income of $1000 is subject to $300 income tax, which gives her an after-tax return of $700, or 3.5 per cent, rather than 5 per cent (see table 3.5, overleaf). If Claire wants to know her real return after tax, then she needs to deduct the effect of inflation, and deduct the income tax payable on the income. This gets tricky but stay with me. Claire’s gross interest is $1000. Her income tax bill is $300. The effect of inflation is 3 per cent, or $600 of her interest income. We then deduct the $300 and $600 from her $1000 interest income, and Claire’s real return after tax is $100, or 0.5 per cent on the $20 000 savings account.

Claire has still protected the purchasing power of her money, but only just. If inflation had been zero, her real return after taxes would be 3.5 per cent. If Claire paid less tax, then her after-tax return would be higher, or if Claire paid more tax, her after-tax return would be lower (see the appendix for income tax rates for 2011–12 and later years).

* The amounts for future years are in future dollars: the figures are not in today’s dollars with the exception of year 10. For year 10, I have provided savings amounts in future dollars, and today’s dollars, and rounded to nearest $500. Today’s dollars are what your future money would be worth if you spent it today (today’s dollars are discussed in more detail later in this chapter). The other assumptions used in table 3.2 are set out in the appendix.

Table 3.5: real return after tax on Claire’s investment (example 7)