CHAPTER 3

Inventory: Essential to Know What You Have

A primary input to MRP is inventory. For the MRP system to create an accurate plan it must have accurate inventory data.

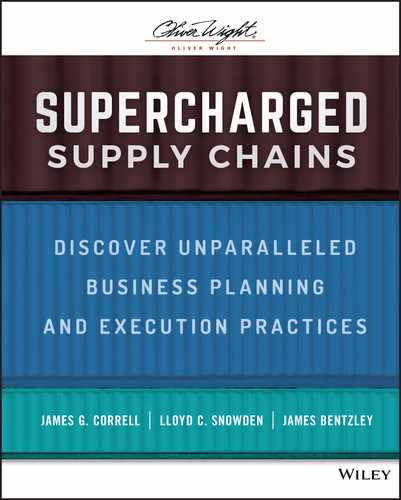

FIGURE 3.1 Business Excellence Planning

The world‐class standard for inventory record accuracy today stands at 99.5%. Very few organizations can claim they are performing at or above this standard. Many achieve good accuracy in automated warehouse locations but fall short in more informal storage, transport, and supply chain areas. The harsh reality is that most companies are still struggling with very inaccurate inventory records.

Oliver Wight himself, during a class that he taught in 1975, asked the class what industry has better than 99.9% inventory accuracy, recognizing that there lots of those locations nearby. No one could answer the question. His response was, “Banks.” They count the money when it goes in and when it goes out. That simply is the basis for inventory accuracy.

In this chapter we focus on the Inventory Status box of Business Excellence Planning, Figure 3.1, and its relationships with the other disciplines.

Imagine if Amazon.com had only 90% inventory accuracy. Would customers accept that 10% of their orders would be shipped later than the delivery promise that comes with their Prime membership? Also consider traceability, which is becoming required at more and more companies. How can you have good traceability processes if your inventory is not accurate? What about your customers and your company? Benefits from more accurate inventory records at all levels of the bill of material include: improved on‐time delivery internally and to customers, improved supply chain efficiency due to the reduction or elimination of unexpected material shortages causing delays, less expediting throughout the supply chain, lower inventory carrying costs, less obsolesce, lower levels of slow‐moving or excess inventory on hand, and the elimination of costly and often inaccurate physical inventories.

The goal is not only to start measuring inventory record accuracy but to continuously improve it. To start the improvement process, this chapter describes a six‐step program that will enable the reader to achieve 95% or better accuracy with less cost.

A Case Study

One of our clients, a multibillion‐dollar corporation, had been operating with high levels of inventory accuracy and with very successful bottom‐line results. A new leadership team, however, thought they could save money by reducing and then eliminating cycle counting (12 people). Initially, they did achieve the savings, and the Six Sigma Team was well rewarded. But then they began to miss deliveries due to shortages caused by inventory inaccuracies. To compensate for the shortages, 40 expeditors were hired to improve customer service. Even with the additional expeditors the situation continued to get worse.

Our client called us back for assistance. When we started to work with them on improving inventory record accuracy, our goal was not only to restore the accuracy quickly, but to ensure that it was sustainable over time. Together, we defined sustainable as:

- Documented: systems (processes and software) that are designed to operate at the lowest possible cost;

- Measurements: that identify the root causes of inventory discrepancies and address any lack of discipline in the systems;

- Shared knowledge: a documented education and training program that cascades throughout all levels of the organization.

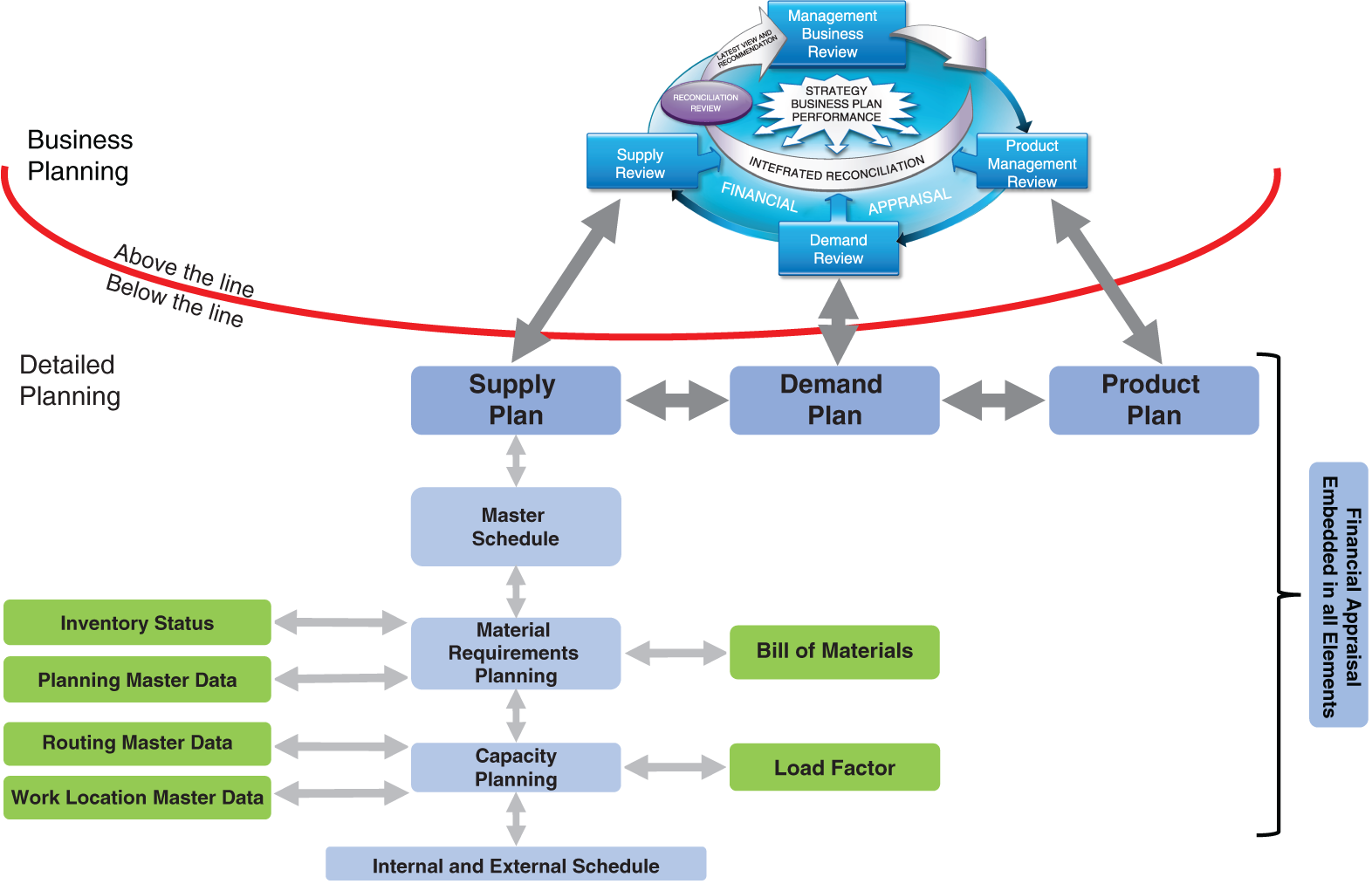

Measuring Inventory Record Accuracy

We also had to bring back the inventory record accuracy definition. This measurement requires that the item number, quantity, and location all be accurate for each location checked. If any one of the three is incorrect, the inventory record for that location is inaccurate (a “miss” rather than a “hit”). In organizations requiring traceability, the addition of lot code or other unique identification code is a fourth element that must be correct in the audit.

The calculation for inventory accuracy is:

The finance department was pleased with this measurement because it was absolute (pluses and minuses did not cancel each other). From a financial perspective, whenever the defined measurement was at 95% (100% for finished goods) or better, the accuracy of the inventory from a financial standpoint was above 99%.

The business's initial goal was to achieve a minimum of 95% inventory record accuracy. Their longer‐term objective (beyond the first year) was to increase their minimum acceptable level to 99.5%, which is world class.

Six Steps to Better Inventory Record Accuracy

In the future, when radio‐frequency identification (RFID) or similar technology is universally implemented, physically counting inventory will no longer be required (see Chapter 17). Of course that assumes that everyone will always follow the process using RFID. People have an extraordinary ability to bypass processes, and automated systems can fail.

Until that time, we recommend six straightforward steps to achieve inventory accuracy target levels. The process is relatively simple, but the implementation is another story. The new process is a disciplined approach, one in which individual and company behavior requires significant change – the real issue.

The six steps to improving inventory accuracy include:

- Step 1: Education and Training: Education is the first and most critical step. If people do not understand why they are doing something, they will not embrace it. Recall that this is a culture change for the company; so, education must start at the very top of the organization and flow down to the rank and file. Commitment without understanding is a liability. So, Leadership and Middle Management as the “leaders” must understand in order to give the proper direction, and the rank and file must understand why, because they are the “doers.” Next is training. Training is the “how” to accomplish the task. Steps 2 through 6 describe the how. Providing a good education and training program addressing the responsibilities and needs of each organizational level is the best way to quickly achieve your inventory accuracy goal. It must address the question, “What's in it for me?” at every level. When that connection is established, the culture change will begin.

- Step 2: Assign Accountability: Inventory accuracy improvement begins with recognition of its importance by people at all levels of the business. That means that all employees must live in that culture. For example, when you go to a bank, there is no doubt about accuracy; it is part of their culture! In a bank there is a culture that expects the cause of an inaccuracy to be fixed immediately – locked down until it is found!

That same culture must exist in your company. It begins with a business policy stating the importance of inventory accuracy, affirming that it is the foundation of all planning and execution processes. The policy must also clearly state that disciplinary action will result if the policy is not adhered to. Finally, the policy statement must be signed by leadership, who must “walk the talk.”

An important lesson to remember: A basic principle of good management is to hold people accountable for only the things they can and do control. This means that the manager of a function, such as supply, must be held accountable for the accuracy of the inventory in their areas because only they can exert both direct and indirect influence over the personnel in those areas. To reinforce its importance, inventory accuracy must be included in their roles and responsibilities and be included in the reward system.

- Step 3: Identify Inventory Areas: Clearly identify every area in the facility that contains inventory and assign an “owner” to it. This is often done for stockrooms but must be expanded to all areas. That includes, for example, supply, quality, in‐transit, and staging areas. All locations in which inventory resides must be included throughout the End‐to‐End Supply Chain. Even the owners of areas that should not have inventory should be held accountable if they allow inventory to be stored in those areas.

An easy test to determine if this step has been taken is to walk through the facility. Where inventory is present, determine the location's identity and who owns the inventory. Who should you ask? Not management, but the employees working in the area. If they say they do not know, that area fails the test.

As a part of the identification step, the owner of the area must be held accountable for its cleanliness and orderliness (5S). Additionally, it should have Team Boards/Displays showing the current inventory accuracy performance for the area and at least the previous three months' results. This type of visual management must be encouraged (see Chapter 18), expected, and owned by the teams that work in those areas, not only for inventory storage areas but throughout the company. It must be part of the company's overall communications to help drive and sustain culture change efforts. One of our clients hang pictures of the people who own an area, along with a posting of the area's inventory accuracy. The company produces small electronic parts, but their inventory accuracy results are regularly above 99.8%.

FIGURE 3.2 Team Boards with Current Team Performance and Actions

To emphasize culture and ownership, we are reminded of when we worked for a heavy equipment manufacturer. Initially, saying that getting employees to adopt this new culture was a challenge is an understatement. We wanted to fence off an outside area where welding department components were stored. The General Manager was against our request because the area was between two buildings and fencing it off would make movement between them difficult. We gave in even though following policy was certainly not a company strong suit, but we did get the GM to sign off on a policy (noted in Step 2) that clearly stated that disciplinary action would be taken if the inventory accuracy policy was violated. The stock keepers told us it would never work without a fence – we were doubtful also. We spent the weekend arranging a third of the area and putting parts away while double‐checking accuracy and clearly marking the area as a “controlled stores area.” The stock keepers encouraged us to come to the area first thing the following Monday morning because one of the supervisors declared he was not going to follow the policy. On Monday morning, the welding supervisor walked out, waved to us, and then took a part (one that he could lift without a forklift or trolley) and carried it into the welding shop. We raced to the GM's office to report the violation. The Plant Manager was in the GM's office when we arrived. The GM said that he would take disciplinary action, but the Plant Manager interrupted, saying that the supervisor was the only employee who knew how to weld the frames so they would fall within required tolerances. The GM told the Plant Manager to start training several people on how to weld the frames and then told his assistant to go get the supervisor. Everyone was watching. When the supervisor arrived, the GM informed him that this was a verbal warning that would be recorded in his file but would be removed it if there were no additional offenses. When other employees questioned the supervisor on why he took the part, he said he was just testing the resolve and would never take anything again. We never had a problem with people taking parts after that. There must be serious consequences for people who deliberately violate policy, process, or instructions. By taking disciplinary steps, management demonstrates walking the talk, showing commitment to their communications and demonstrating that if others do it, they can expect the same consequence. This incident was not about the supervisor but about whether the GM would enforce his policy. Hopefully much less severe disciplinary action is required to ensure that policies and procedures are followed in your company.

Methods of gaining and maintaining inventory accuracy can be much less authoritarian. In the middle of a factory we worked with, there was an open store that was staffed only on the day shift but accessed by operators on two shifts. Accuracy was poor and was causing problems completing planned assemblies. The solution was simply to educate operators and to ask them how the situation could be improved. The improvements accepted included an increased focus on kitting accuracy for assemblies scheduled on the shifts, and a clipboard at each storeroom entry area for people to log what they took on the occasions they still had to serve themselves after hours. People felt involved in both the problem and the solution, accuracy increased to well above the minimum level, and barriers between production, stores, and planning were reduced.

Another good example occurred at a very large manufacturer of branded consumer foods. The warehouse employees began to own the Inventory Record Accuracy program to the point they changed the sign on the stores office door to read “Inventory Record Accuracy Team.” At the time of their Class A assessment, they were achieving IRA accuracy of 99.9%.

- Step 4: Design “Simple” Systems: A “simple system” (process/software) is one that a computer‐literate person can learn and operate effectively with a reasonable amount of training.

For example, one company we worked with initially implemented a system with 27 different inventory transactions. The result: due to the system's complexity, the people recording the transactions were constantly making mistakes. The number of transactions was reduced to five (issue, receive, stock to stock, scrap, hold), after which inventory accuracy skyrocketed. Once again, educate the individuals first, get them to then apply their new knowledge to the process design, ensure the software reflects this new process, and then train them on the processes and the software transactions.

Automation can have a huge impact on inventory accuracy if movement of material can be automatically logged. The six steps to improved Inventory Record Accuracy must be followed up and supported by whatever technology is currently available. As investment is made, automatic transaction recording should be incorporated when possible. Although this is not necessarily simple technology, it leads to a simple process to operate accurately. See Chapter 17, Technology Enhancements.

- Step 5: Be Easy to Count: For inventory to be accurate, it must be counted with some frequency to confirm that inventory processes are being followed and that the planning system contains valid data. For people to count inventory accurately, inventory must be made easy to count. Take eggs as an example. How long would it take to count a case full of eggs if they were randomly put into a large container? Then consider how long it would take to count them as a store receives them – 12 to a carton, 20 cartons to a case, or 240 eggs. If an internal or external supplier has packaged its product so that it is easy to count and has historically demonstrated 99.5% accuracy, only a spot or random audit is required.

Typically, the first answer to the challenge of making inventory easy to count is to have the packaging specialists define the packing requirements for each item. This is absolutely the right starting point for items requiring special packaging for protection but is absolutely the wrong answer for most items. It transfers a simple process into a bureaucracy with all the delays that go with it. This is not a “Six Sigma” project; it is a “One Sigma” project. Anyone who handles inventory can make it easy to count with a little education and training.

One excuse for not addressing the easy‐to‐count requirement is that it will cost more. Our experience is exactly the opposite. When people understand what is required and do it right the first time, it costs less. Significant costs can be saved throughout the supply chain when the inventory is easy to count.

FIGURE 3.3 Inventory, with Improved Accuracy Spot or Random Audits Used

- Step 6: Adopt Cycle Counting: A bank teller balances to the penny their “inventory” at the end of each day. This is not possible in a supply chain environment because each SKU would have to be balanced at the end of every day or even every shift and would interrupt supply.

Consequently, some type of cycle‐counting process must be used and has been proved to be both effective and efficient. However, be forewarned that cycle counting itself does not improve inventory record accuracy. The reason for cycle counting is to locate, identify, and eliminate the root cause of inventory errors. Resolving the root causes of errors is what drives significant and rapid inventory record accuracy improvement.

There are numerous cycle‐counting processes. Considering that 99% of the reason for cycle counting is to identify errors, drive root cause analysis/resolution, and be cost effective, only one cycle‐counting process meets all criteria: Process Control Cycle Counting. This methodology gets its efficiency from counting what is in contiguous locations and comparing the results with what is recorded in the planning system. Process Control Cycle Counting allows the cycle counter to spend time efficiently counting and not moving from one location to another. Process Control Cycle Counting, combined with Step 5 (be easy to count), allows a cycle counter to perform more than 300 counts per day. As inventory accuracy levels approach and exceed 95% over a sustained period of, for example, three months, a large number of counts are required to find enough errors to do a root cause analysis.

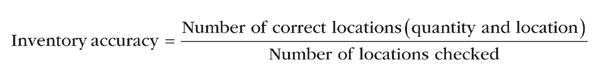

Next is a simple example of Process Control Cycle Counting. The process starts with a printout by location, as shown in Figure 3.4, with room to record the result. Note that cycle counters become owners of the cycle counting process and storage area personnel become protective of the validity of Inventory Record Accuracy (IRA) results to the point that they are provided the system inventory information before they begin their cycle counts each day.

FIGURE 3.4 Process Control Cycle Counting Template

Principles:

- Easy to count – count it

- Obvious error – count it

- Not obvious error/hard to count – audit

Methodology:

- Location A100 is easy to count so counting is quick and efficient.

- Location A101 is easy to count because it is in boxes of 100 – four boxes of 100 and three loose – so count it.

- Location A102 items are just loose in the bin, but it is obvious that there are nowhere near 229 in the bin – so count it (when counting, consider placing some into packaging so next time it will be easy to count and request purchasing or factory to package the items properly in the future).

- Location A103 is not easy to count because items dumped into the bin, but it looks reasonably accurate so will be recorded as a completed count but not included in the accuracy count. When the bin gets down to a reasonable level it is then counted and packaging occurs. If properly educated the cycle counters can do an incredible job of estimating.

- Non‐storage location, a traffic aisle, should not have any inventory stored in it, and is not on the cycle count audit list, but has two pallets of product sitting in the aisle. Count the items, record the count as a miss, and add it to the cycle count results for the day.

Many people object to the count being available to the cycle counter because they might just take the count and not do their job. Without the count, Process Control Cycle Counting can't be done. This whole book is about training, engaging, and trusting your employees to their job if properly educated (why) and trained (how); see Chapter 18.

Inventory counts need not be performed only by Cycle Counters. With appropriate education and training there are times that others can contribute to the cycle counting process. Following are a couple of examples.

- When an item is pulled from stock creating a zero balance at that location, there should be a verification of that zero balance that can be included in cycle count results. The system says that we should now be at zero balance and the warehouse/delivery person can easily verify and report that the actual balance in this location is or is not zero.

- When inventory is being put away (a standard amount at a standard location), a balance verification is relatively easy and can be performed by the person transacting that move.

Whenever errors are found, root cause analysis and problem resolution must follow quickly. Cycle counting and root cause analysis are a waste of time if the problem is not resolved. Therefore, going back to Step 2 (assign accountability), the person who is responsible for the area's inventory accuracy must have cycle counter(s) report directly to them.

Below are some tips regarding cycle counting:

- Root cause error analysis should be performed immediately upon discovery of an error, not just during the cycle counting process.

- Designated person – most often, a designated person/team (such as a Cycle Counting Team) performs the analysis, especially if it is a complex issue.

- Metrics must be calculated and tracked not just of the accuracy percentage, but of the frequency of error root causes. This analysis will point to system problems, even if you believe the processes and systems are operating as designed.

- Systems (processes/software), including documentation, should be fully reviewed and verified/validated during the root cause/corrective action process and periodically for continuous improvement.

When the system (process/software) is validated, errors are almost always due to lack of process discipline. Lack of discipline must be addressed by the area owner. Timeliness of transaction recording is one of the most important factors in inventory accuracy. When you use a debit card on a day of shopping, your bank doesn't wait until the end of the day to deduct your expenses, it does it immediately as you shop!

Another key organizational consideration and the reason to have storage area employees conduct cycle counts is that it is much faster and efficient to take corrective action when direct reports are exposing accuracy problems rather than have another outside department exposing and reporting them. Defensiveness is automatically eliminated.

Audits

The objective of cycle counting is to achieve an unbiased measure of inventory accuracy trusted by everyone. While our experience is that qualified cycle counters can be relied upon without question, it still makes sense to conduct occasional audits of the results conducted by knowledgeable and trained people. While similar, an audit is different from a cycle count. As stated before, an area inventory process owner has the Cycle Counters as direct reports but, being human, will have a vested interest in meeting accuracy objectives and may possibly bias the results. To avoid this, we encourage audits to be conducted by people with no vested interest, such as Finance or Quality. The auditor's job is simply to verify the accuracy of the cycle count. Should errors be discovered, understanding and root cause analysis remain the responsibility of the inventory owner, who would then adjust the figures accordingly. If this were to be carried out for the inventory owner by the auditors, there will be no learning or ownership of the required actions. This is the second objective of the audit. It should be noted that any inventory record errors discovered by the auditor are not changed in the system without verification by the inventory owner of the inventory. The auditor should not have the ability to change counts.

Technology Enhancements

Chapter 17 is devoted to technology enhancements, with some that will facilitate inventory accuracy procedures. In an effort to collect more information about technology enhancements being used today, we checked in with a huge distribution warehouse. There was some resistance to share what could be a competitive advantage, but we were provided some helpful information. First, we learned that warehousing is highly automated. While that is interesting, automation is not the subject of this chapter. This chapter is focused on maintaining accurate inventory. The following is what we discovered at this distribution warehouse:

- Suppliers: They do not count the inventory when it comes in the door but simply take the suppliers' counts.

- Cycle Counting: They do perform cycle counts. The Process Control Cycle Counting methodology described does not work in quite the same way because of the automation. Cycle Counters cannot walk down the aisles to count contiguous locations. Instead, they select the items/locations and have the computer and automated system deliver the contents to their cycle counting station.

- Ownership: As we suggest above, cycle counters and auditors are not authorized to change the count in the system but must have the inventory owner approve the adjustment.

- Accuracy: The inventory accuracy level is very high (but they would not share their percentage or their calculation method).

We could not understand how this company has such reportedly high accuracy when they don't count or even audit supplier counts when received. They explained that if a supplier provides an incorrect count, it knows it is in big trouble and their contract will be terminated quickly. They know their counts must be accurate. They could not have given us a better answer.

Summary

Customer expectations for high on‐time delivery performance and low prices have increased, and scrutiny of corporate bottom lines has never been more intense. With these added pressures, there is no excuse for having inventory accuracy less than 95% using our earlier definition, knowing that the norm for your competitors is much higher. The six steps described previously provide a perfect way to begin your journey to best practice Inventory Record Accuracy results.

Far beyond 95% accuracy, Six Sigma inventory record accuracy levels are an achievable goal, if the process is designed correctly, people are adequately educated and trained on the process and held accountable. Specific training on cycle counting, root cause analysis, and empowerment to resolve problems is essential for this performance level.

A closing comment: Inventory management is not rocket science. It is simply common sense based on an understanding of how an accurate inventory enables you to better manage your business. The simple truth is that people must realize that if they need inventory, they must formally request it, and if they add inventory, they must formally transact that receipt.

For more information about improving inventory record accuracy, we recommend Inventory Record Accuracy: Unleashing the Power of Cycle Counting, second edition, by Roger B. Brooks and Larry W. Wilson (John Wiley & Sons, 2007).

For additional but more specific reading please visit the Oliver Wight Website and gain access to the extensive library of White Papers.