Chapter 2

Supply Chain Strategy

![]() LEARNING OBJECTIVES

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

- Define supply chain strategy and explain how it supports the business strategy.

- Explain how proper supply chain design can create a competitive advantage.

- Identify and explain the building blocks of a supply chain strategy.

- Explain differences in supply chain design based on organizational competitive priorities.

- Explain how productivity can be used to measure competitiveness.

![]() Chapter Outline

Chapter Outline

- What Is Supply Chain Strategy?

Strategic Alignment

- Achieving a Competitive Advantage

Cost-Productivity Advantage

Value Advantage

SCM as a Source of Value

- Building Blocks of Supply Chain Strategy

Operations Strategy

Distribution Strategy

Sourcing Strategy

Customer Service Strategy

- Supply Chain Strategic Design

Competing on Cost

Competing on Time

Competing on Innovation

Competing on Quality

Competing on Service

Why Not Compete on all Dimensions?

- Strategic Considerations

Small Versus Large Firms

Supply Chain Adaptability

- Productivity as a Measure of Competitiveness

Measuring Productivity

Interpreting Productivity

- Chapter Highlights

- Key Terms

- Discussion Questions

- Problems

- Case Study: Surplus Styles

Walk into a Zara clothing store, whether in New York, Miami, Atlanta, or London, and you experience the feel of high fashion. The ambiance is contemporary, with dim lighting and the beat of modern music pulsating in the background. The clothing styles on the racks capture the latest fashion for men and women, and there is a wide array of choices. Surprisingly, however, the price point is reasonable and much lower than found at any comparable retailer or boutique. This is what makes Zara unique.

Zara is the highly successful Spanish retailer with over 1,500 stores worldwide that launches around 10,000 new fashion designs each year. It is known for its quick design and delivery, and needs just two weeks to develop a new product and get it to stores, compared with a six-month industry average. Zara has been called a fashion imitator. It focuses on copying the latest fashion items customers want and delivering them at a considerably lower price. Unlike other retailers, it does not advertise and does not promote season's trends to influence shoppers. To achieve this level of success Zara has a most unusual strategy and its secret lies in supply chain management (SCM).

Zara is a vertically integrated retailer and controls most of its supply chain, including sourcing, design, production, and distribution. This is highly unusual in an industry that overwhelmingly tends to outsource fashion production to low-cost countries. In fact, while most competitors outsource all production to Asia, Zara makes over half of its merchandize at a dozen company-owned factories in Spain and Portugal, where labor is cheaper than in Western Europe. Only items with a longer shelf life, such as basic T-shirts, are outsourced to low-cost suppliers in Asia and Turkey. A large part of this is to support its strategy of offering high fashion items. To accomplish this, Zara designers are located on the floor of its manufacturing facility in order to shorten production time, and have weekly talks with store managers across the globe to find out what customers want.

Borrowing best practices from the Toyota Motor Corporation, Zara has a very efficient and lean production process. It carries little inventory of expensive items. However, to give itself flexibility and offer a wide product assortment, Zara carries excess inventories of inexpensive items. This includes buttons and zippers which Zara's designers can use to create different items. As a result, Zara can offer considerably greater product variety than its competitors. Zara produces about 11,000 unique items annually compared to 2,000 to 4,000 items for key competitor. The company can design a new product and have finished goods in its stores in four to five weeks. This short production cycle means greater success in meeting consumer preferences. If a design doesn't sell well within a week, it is withdrawn from shops, further orders are canceled and a new design is pursued. No design stays on the shop floor for more than four weeks, which encourages Zara's shoppers to make repeat visits. Customers know that end-of-season markdowns, so common in the retail industry, do not occur at Zara so they feel a greater need to buy the item they have in hand.

Zara uses its supply chain strategy as a competitive weapon. For Zara, this has proved to be a very successful decision.

Adapted from: “Zara: Taking the Lead in Fast-Fashion.” Bloomberg Businessweek. April 4, 2006.

WHAT IS SUPPLY CHAIN STRATEGY?

A company must have a long-range business strategy if it is going to maintain a competitive position in the marketplace. A business strategy is a plan for the company that clearly defines the company's long-term goals, how it plans to achieve these goals, and the way the company plans to differentiate itself from its competitors. A business strategy should leverage the company's core competencies, or strengths, and carefully consider the characteristics of the marketplace.

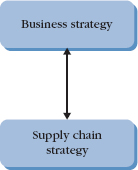

Supply chain strategy is a long-range plan for the design and ongoing management of all supply chain decisions that support the business strategy. Consider that the design of a supply chain should differ based on how the company intends to compete in the marketplace. In order to maintain competitiveness companies must design their supply chains to be aligned with their business strategy, to satisfy the needs of the customers, take advantage of the company's strengths, and remain adaptive. This relationship between the business strategy and the supply chain strategy is shown in Figure 2.1.

Consider the case of Zara discussed in the chapter opener. Zara's business strategy is to produce and deliver look-alikes of the latest fashion trends to customers at an affordable price. Zara understands that the key to accomplishing this is through a well-thought-out supply chain strategy designed to support its goals. For this reason the company chooses to be vertically integrated, giving it speed, flexibility, and control of product design and delivery. Also, the company chooses not to outsource most of its production as doing so would hurt Zara's ability to quickly adapt to fashion trends. As we can see, Zara's supply chain strategy is designed to enable the company to achieve the goals set by its business strategy.

FIGURE 2.1 Supply chain and business strategies are aligned.

STRATEGIC ALIGNMENT

It is important to remember that there must be strategic alignment between the business strategy and supply chain strategy. A company's supply chain strategy should be developed to drive and support its business strategy. Consider an electronics company that has formulated a business strategy to compete on delivery excellence, such as order-fulfillment time. As a result, the supply chain strategy may be designed for speed of delivery although perhaps at a higher cost. Now imagine that the company decides to change its business strategy to compete on cost rather than delivery, considering current market competition and customer perceptions of value. If this change in business strategy is not communicated to SCM, the supply chain will continues to focus on delivery rather than cost. The company will continue to excel at delivery, while incurring a higher cost, and not meeting the business goals set for the company.

The supply chain should not be designed to merely mimic its competitors or solely focus on cost cutting efforts. The supply chain should be designed and positioned to support the strategic direction of the firm, giving it a competitive advantage in the marketplace. As we will see later in this chapter, supply chains can have a very different design based on their competitive focus. Today's most successful companies, as illustrated by Zara, have achieved world-class status in large part due to a skillfully designed supply chain strategy that is manifested in the design of its supply chain. Companies all over the globe understand that they cannot achieve the competitiveness needed to survive and thrive in the current global economy without strategically thinking about their supply chains.

In addition to SCM, all organizational functions should be designed to support the business strategy. This includes marketing, operations, distribution, purchasing, and even finance. In addition, the organizational functions should support each other. This functional support is especially important for SCM given its boundary spanning nature and high dependence on logistics, marketing, and operations. This functional unity and support of the business strategy will enable the organization to function in a synchronized manner.

ACHIEVING A COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE

Given the highly competitive environment of today's marketplace, seeking a sustainable competitive advantage has become a top business concern. Unlike in the past, where creative marketing initiatives were sufficient to promote products, today's marketplace requires a higher level of strategic positioning. In this section we will look at how a well designed supply chain can provide companies with needed competitive advantage.

To understand supply chain competitiveness, let us look at the concept of competitive advantage. At the most basic level, corporate success in the marketplace can result from two aspects. The first is a cost or productivity advantage, the second is a value advantage. In the first case, advantage comes from offering the lowest cost product or service. In the second case, the advantage comes from providing a product with the greatest perceived differential value compared with its competitors. In the ideal situation a company would have both a cost and a value advantage. These two basic advantages provide a basis of strategy and competitive positioning. We now look at these strategic dimensions in more detail.

COST-PRODUCTIVITY ADVANTAGE

Every marketplace typically has one competitor who is the low-cost producer and who has the greatest sales volume in the particular market. Consider Wal-Mart that competes on cost and, as a result, is a leader in sales volume in the retail market. In fact, there is much evidence to suggest that a large volume can contribute greatly to a cost advantage. One factor contributing to this are economies of scale that enable the company to spread its fixed costs over a greater volume.

Another factor contributing to this is the impact of the experience curve—derived from the traditional concept of the learning curve. The learning curve tells us that with experience workers become more skilled in processes and tasks and do them more efficiently. The same is true of organizations. Organizational costs are reduced due to experience and learning effects that result from processing a higher volume. This is the experience curve, which describes the relationship between unit costs and cumulative volume, where the cost per unit of a product decreases with increased volume.

Based on the experience curve, it has been assumed that the only way to gain cost reductions, and compete on a cost-productivity advantage, is to increase sales volume. Although this is one way to achieve a cost advantage, another way is through an efficient supply chain network. The reason is that an efficient supply chain network can increase efficiency and improve productivity, thereby reducing overall cost per unit.

VALUE ADVANTAGE

Consider that customers do not buy products but rather the benefits or value provided by those products. Therefore, there may be multiple products that provide customer value. Also, it is not just the stand-alone product that is the ultimate customer's desire, but many intangible benefits a product offers. For example, customers will often buy a product for its image and reputation rather than pure functionality. On the other hand, a product may be purchased due to performance value that it offers over its competitors and rivals.

Wal-Mart

Sam Walton was a strategic supply chain visionary who developed the low-cost responsive retail strategy that is supported by a supply chain strategy of not buying from distributors but rather directly from manufacturers of a broad range of merchandise. In fact, Wal-Mart's legendary partnership with Procter & Gamble (P&G), where replenishment of inventories is done automatically, illustrated to other companies the power of integrating with key suppliers. These supply chain actions were designed to help Wal-Mart meet its overall competitive strategy, which is to provide its customers with a wide product offering at a low price. Wal-Mart has continued this strategy by using technology, such as RFID, to cut inventory costs and maintain its cost position. This has helped Wal-Mart become the world's largest retailer.

In 2009, Wal-Mart extended this supply chain strategy by focusing on being “best in market” rather than “world class,” when serving overseas markets. This means that the company uses different levels of technology and cost in their various supply chains based on the needs of the each specific market, rather than having supply chain uniformity.

Wal-Mart's many supply chains are designed to differ based on the needs of the specific markets they serve.

Adapted from: Cook, James A. “Wal-Mart Builds Best-in-Market Supply Chain for Overseas Stores.” DC Velocity, October 8, 2009.

An important competitive advantage for companies is to distinguish their products or services in some way from their competitors. Otherwise, their products will be seen as a commodity. When a product is viewed as a commodity, it is typically bought on the spot market for the lowest price. Therefore, it is important for companies to add value to the products and services they offer that differentiate them from their competitors.

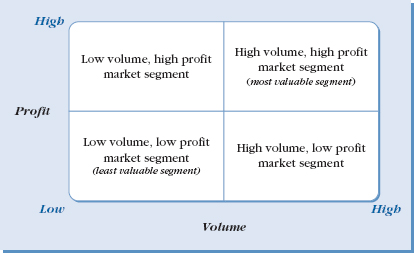

Let's look at some of the ways by which companies can gain a value advantage. One way is by segmenting the market and identifying “value-segments” in the marketplace. This means that different customer groups place value on different product benefits. This analysis permits the company to see which market segments place value on what product features. It may then be possible to create a differential appeal tailored to different segments. For example, auto manufacturers create different versions of the same vehicle to compete in different market segments, such as a basic two-door model versus the four-door, high-performance model. These options enable the manufacturer to satisfy the value of different market segments.

In addition to the product itself, companies are increasingly focusing on service as a way to add value. In fact, competition based on technology and product alone is becoming increasingly difficult. One reason for this is that technology and best production practices are becoming more of a commodity. Service is one dimension that is more difficult to replicate. This is creating a new way for companies to seek differentiation and a competitive advantage. Service addresses issues such as developing relationships with customers, delivery, after-sales support, financial packages, technical support, maintenance, and other similar services.

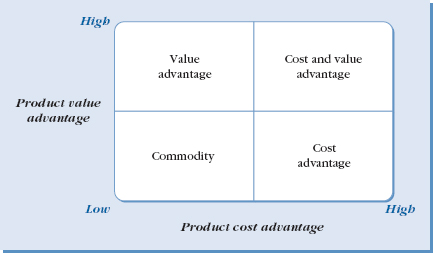

FIGURE 2.2 Competitive advantage matrix.

Companies can gain competitiveness either through a cost-productivity advantage or a value advantage. In practice, however, some of the most successful companies are those that position themselves based on both. This is shown in Figure 2.2. Let's now discuss the options provided to companies by this matrix.

The least desirable place for a company to be on the matrix shown in Figure 2.2 is in the “commodity” section, namely the bottom left-hand corner. The reason is that here the company has not differentiated its product from that of its competitors. The result is having to sell the product at the lowest possible price. For companies to remain competitive, they usually try to move to a more desirable competitive position. One option is to move to a position of cost leadership. Another is to move toward value leadership. The ideal position, however, is at the top right-hand corner where a company has competitive positioning along both cost and value dimensions.

SCM AS A SOURCE OF VALUE

SCM provides a powerful way for companies to achieve a cost-value advantage over their competitors. For example, improvements in the supply chain can dramatically reduce inventory, distribution, and coordination costs. This is a highly effective way to move up the quadrant to a position of cost-value leadership. In later chapters of this text, we will look at specific ways that companies can achieve this, such as developing a lean supply chain and implementing six-sigma quality.

Toyota Motor Corporation

The Toyota Motor Corporation is viewed as a leader in the auto industry and a model of strategic supply chain design. The company has experienced unparalleled growth over the last two decades. Toyota understands that it must have an effective global supply chain strategy to continue this level of success. This has involved building superior strategic alliances with its suppliers, designing an agile global distribution network, and positioning production facilities strategically. In order to have a highly responsive supply chain, Toyota's strategy has been to open factories in every market it serves. An important element of this decision was the production capability at each plant. Prior to l996, Toyota used a supply chain strategy where every plant was specialized and capable of supplying only local production. Since the early 2000s, however, Toyota redesigned its network for plants to be more flexible and to supply multiple markets, enabling it to easily shift production for one market to another as needed. This strategy has enabled Toyota to remain agile.

Another way that firms can move to a cost-leadership position is to develop strategic differentiation based on service excellence. Therefore, the “good” itself remains a commodity, but the total product package is now differentiated from other customers. This is a good strategy as today's customers demand greater responsiveness and reliability from their suppliers. Customers want shorter lead times, just-in-time deliveries and services that help them do a better job of serving their own customers. SCM can provide this type of advantage.

Yet another option is through the introduction of new supply chain technologies. Such technologies can provide an opportunity for a company to lower its cost over competitors. Such has been the case with Wal-Mart, as we discussed earlier. However, this option is typically available to competitors as well, particularly in today's marketplace where information travels rapidly. Still, this strategy may pre-empt competition if the company uses the technology in a way that provides greater customer value.

BUILDING BLOCKS OF SUPPLY CHAIN STRATEGY

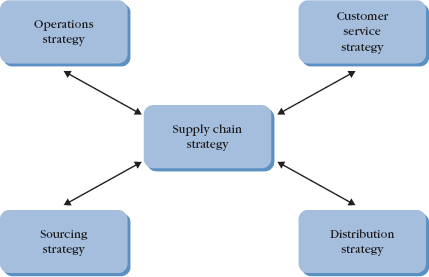

Strategic SCM involves designing a supply chain that is uniquely configured to meet the company's overall business strategy. This is especially challenging given the boundary-spanning nature of SCM. Consequently, the development of a supply chain strategy involves consideration of each of the traditional business functions and their impact on the supply chain. These are the building blocks of a supply chain strategy and include the following:

- Operations strategy

- Sourcing strategy

- Distribution strategy

- Customer service strategy

Historically, companies tended to either make decisions regarding each of the above functions informally, or make decisions about them in isolation of each other. As we mentioned earlier, successful companies understand that organizational functions are interdependent. For example, marketing cannot sell products that operations cannot make and vice versa. Supply chain strategy is directly impacted by the decisions of the four building blocks and how they are used to support the business. This is shown in the diagram in Figure 2.3. Let's now look at these individual building blocks and how they impact the development of the supply chain strategy.

OPERATIONS STRATEGY

The operations strategy of a company involves decisions about how it will produce goods and services. The operations strategy determines the design and management of a company's manufacturing process, the design of internal processes, use of equipment and information technology, as well as the types of employee skills needed.

FIGURE 2.3 The building blocks of supply chain strategy.

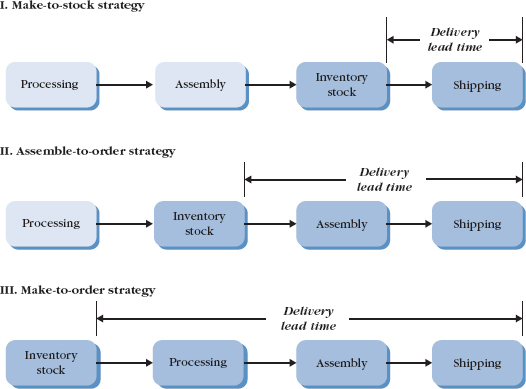

One of the most important aspects of operations strategy is the degree of product customization it offers, called the product positioning strategy. This decision directly relates to the form in which the company stores its finished products and the length of delivery lead time it can provide to its customers. There are three options in this area:

- Make-to-stock

- Assemble-to-order

- Make-to-order

Make-to-stock is a strategy that produces finished products for immediate sale or delivery, in anticipation of demand. Companies using this strategy produce a standardized product in large volumes. Typically this strategy is seen in assembly line type operations. Delivery lead time is shortest with this strategy, but the customer has no involvement in product design. This is the best strategy for standardized products that sell in high volume. The production system is set up to produce large production batches that keep manufacturing costs down, and having finished products in inventory means that customer demand can be met quickly. Examples include off-the-shelf retail clothing, soft drinks, standard automotive parts, or airline flights. A hamburger patty at a fast-food restaurant such as McDonald's is made-to-stock. Customers gain speed of delivery with this strategy, but lose the ability to customize the product.

Assemble-to-order strategy, also known as built-to-order, is where the product is partially completed and kept in a generic form, then finished when an order is received. The inventory that the company holds is that of standard components that can be combined to customer specifications. Delivery time is longer than in the make-to-stock strategy, but allows for some customization. This is the preferred strategy when there are many variations of the end product and the company wants to achieve low finished-goods inventory and shorter customer lead times than make-to-order can deliver. Examples include computer systems, pre-fabricated furniture with choices of fabric colors, or vacation packages with standard options.

Make-to-order is a strategy for customized products or products with infrequent demand. It is used to produce products to customer specifications after an order has been received. The delivery system is longest with this strategy and product volumes are low. Examples are custom-made clothing, custom-built homes, and customized professional services. Companies following this strategy produce a final product only when a firm order has been received. This keeps inventory levels low while allowing for a wide range of product options. The differences in the three strategies are illustrated in Figure 2.4.

Changing the company's operations strategy from one type to another can be a source of competitive advantage. It may not be possible, however, to move from one extreme position to another, such as from make-to-order to make-to-stock. In that case a company would be completely changing its product offering. One option might be to occupy a position of middle ground, such as in an assemble-to-order strategy.

FIGURE 2.4 Product positioning strategies.

For example, moving from make-to-stock to assemble-to-order can serve to improve customer service while reducing inventory. The reason is that in a make-to-stock strategy inventories of all finished goods are carried in stock. This may result in there being too much of one type of inventory and not enough of another. An assemble-to-stock strategy can result in storage of considerably lower amounts of inventory, primarily held in a generic form. The final assembly can then take place when demand for specific products is known with greater certainty.

In some industries, however, it may be difficult to pursue any strategy other than make-to-stock given high manufacturing costs. For example, automobile manufacturers have historically used a make-to-stock strategy, though some have moved to an assemble-to-order, particularly in the high-end European market. The problem with an assemble-to-order strategy in this market is that there is potentially a countless number of end product configurations. Trying to satisfy the many different product variations makes it difficult to maintain a competitive lead time. One way to accomplish this is to have suppliers fully integrated into the production process. In addition, it is highly expensive to incur the cost of changing the manufacturing process (called “setup”) so that unique characteristics can be produced. The easiest alternative is to have limited product options, as has been done by most automakers. Otherwise, manufacturing costs become prohibitive.

Operations strategy, like any strategy, is a dynamic process rather than a static one-time decision. It is also highly related to the product life cycle. In the early stages of a product life cycle, demand for a product is uncertain and companies are better off with a make-to-order strategy as key product attributes are still unknown. As the product moves through its life cycle, companies often move from a make-to-order to an assemble-to-order to reduce inventories while making sure that there is product availability at a competitive price. Products in the mature stage of their life cycles tend to be produced by manufacturing processes that are designed for make-to-stock. The reason is that in the mature stage of its life cycle a product's market is predictable in both its demand and volume. Consequently, the operations strategy needs to change with the product as the product moves through the different life-cycle changes.

DISTRIBUTION STRATEGY

A company's distribution strategy is about how it plans to get its products and services to customers. An important decision here is whether the company is going to sell directly through distributors or retailers (channel intermediaries) or directly to customers, such as using the Internet or a direct sales force. This type of direct-to-customer strategy is the model historically used by Dell. However, in 2009, Michael Dell announced that Dell Computer Corporation would be changing its distribution strategy to sell through retailers such as Best Buy. This change in Dell's distribution strategy is in response to changing markets and shows the importance of this strategy for competitiveness.

The selection and development of a distribution strategy requires doing market segmentation, analyzing the perceived value of each segment, as well as the competition and profitability of each segment. The best distribution strategy varies depending upon which market segment the company is trying to reach. Consequently, it is best to use a mix of distribution strategies that vary by market segment and target a particular market. Market segmentation is also valuable to determine which segments should be first to receive the product in situations of product shortages. In Chapter 4 we will discuss market segmentation and implications on SCM in more detail.

A good example of how market segmentation can be used to select different types of distribution strategies is illustrated by the bottled water industry. Most companies in the industry have two markets. One is spring water and the other is distilled water. Spring water is collected and bottled on-site, while distilled water can be bottled at any one of many water sources using any local bottling company. Companies in this industry use two different distribution methods to serve their customer segments. The first strategy is using traditional retail distributors who serve the retail customers and the second is direct to customer, where the water is replenished on-site at either the customer's home or office. Further, the two distribution channels have different versions depending upon which market segment they serve. To satisfy each segment, the supply chain uses different processes, assets, and has different relationships.

A new entrant in the bottled water industry would have to make some important decisions. First, the company might have to decide whether it wants to sell to distributors who probably have a good relationship with the retailers, or sell directly to the retailers. If a company chooses to use distributors, it will have to make decisions such as whether to purchase an integrated order management system such as that of the distributor. Also, it may have to decide which distributors will be the company's strategic partners and for which the company may be willing to carry extra inventory. These decisions should not be made in isolation, but in concert with the overall business strategy, as they could have a profound impact on profitability and efficiency of the supply chain.

SOURCING STRATEGY

Sourcing strategy relates to which of a company's business it is going to outsource versus the ones it will retain internally. This includes decisions regarding supplies and component parts, as some companies choose to make these themselves. This decision has great bearing on supply chain strategy as it directly imposes a particular aspect of the supply chain structure—relationships with outside entities.

The process of developing a sourcing strategy typically begins with a company analyzing its existing supply chain skills and expertise. The company has to identify what it is that it is really good at and what areas of its expertise have the potential to become strategic differentiators. These activities have to be kept in-house and made even better. On the other hand, activities with low strategic importance that can be performed by another company are good options for outsourcing.

Outsourcing means that a company has hired a third party or a vendor to perform certain tasks or activities for a fee. This could range from the mundane, such as outsourcing proofing of legal documents or outsourcing the management of unimportant inventory items, to the outsourcing of the entire manufacturing process of even the entire management of the supply chain.

Outsourcing enables companies to quickly respond to changes in demand, enables them to quickly build new products or gain a competitive position in the marketplace. Through outsourcing a company can leverage another company's capacity and its expertise. This provides a tremendous amount of flexibility that is necessary in today's marketplace, which demands high specialization despite that no company can do everything well. In fact, that is a very important realization for companies—the fact that they cannot effectively do all tasks well and may need to turn to vendors for help. Outsourcing something like communication network management to a company that is a leader in that area can provide an advantage. Outsourcing, most importantly, allows a company to focus on their core competencies. The famed management guru Tom Peters was known as saying: “Do what you do best, and outsource the rest!”

Outsourcing used to be considered by managers as a simple make or buy decision, where they considered the cheapest alternative. Today, however, managers understand that sourcing is a strategic decision. It may be more expensive to purchase the expertise of an outside vendor, but it may prove to be more time-saving and lucrative in the long run. Before making the final decision, however, companies need to fully consider the risks associated with outsourcing. Whenever control over a task is placed in the hands of a third party there is a risk of loss of control. The more important the outsourced task, or the more strategic in nature it is, the greater the risk. The introduction of new products and ensuring that the configuration of the supply chain supports the competitive lead times are activities that typically should not be delegated to a third party.

Other considerations related to outsourcing are whether the skills or activities that are being outsourced are going to continue to be maintained internally. This is an important decision as, on the one hand, a company may not want to duplicate what is already being outsourced. On the other hand, a company may choose not to eliminate the activity internally as it may completely lose the capability and it may find that it is completely dependent upon the vendor. A few years ago a divestiture of an outsourcing agreement occurred between ATT and Bank One. ATT was responsible for all of the bank's information technology needs. However, Bank One decided that even though IT was not its core competency, it was a highly important capability given that it directly supports the bank's core competency. Consequently, it brought the function back in-house.

Outsourcing tasks or functions to third parties can provide a significant competitive advantage. The first advantage is cost, as a third party may be able to offer products or services at a lower price. The reason is that they have reached economies of scale in their production systems for producing this type of product or service. Another advantage is that it enables a company to expand its offering into new markets or geographic areas through outsourcing partners that have reach in those areas. For many companies this type of access might not be possible if it were not for outsourcing. Finally, outsourcing may help companies achieve state-of-the art technological capability virtually overnight, which would not be possible otherwise. In fact, for many companies it requires a significant financial investment to develop these capabilities internally and they simply may not have the resources to keep up. Outsourcing enables a company to take advantage of this expertise from another firm.

All outsourcing engagements, however, entail certain risks that companies need to consider when making the outsourcing decision. In general, more sophisticated sourcing engagements bring greater benefits, but also involve significantly higher risks. A number of risk factors need to be considered before a firm passes responsibility to external vendors.

One risk to consider is the risk of loss of control. As the scope of the task passed to the vendor increases, the ability to retain control of the task or function decreases. The purpose of outsourcing is to tap into the talent and unique capability of the vendor. However, unless very specific outcome expectations are set up, the final outcome may not meet expectations. Identifying key performance metrics and their values is a challenge, particularly for service types of tasks where the final “product” is intangible and often difficult to quantify. For small firms this can be particularly damaging as internal processes are less insulated from disruption.

Another risk to consider is dependency risk. As a firm engages in more sophisticated sourcing engagements it often tailors and adapts its operations to match those of its vendor. By doing so the firm may benefit by taking advantage of the vendor's economies of scale. This is particularly true in cases that require specialized technology and equipment, and specialized training of staff. However, these arrangements create a risk that the firm will become overly dependent on the vendor. This can have short-term problems, such as lack of performance on the part of the vendor that disrupts operations. It can also have strategic consequences, as the firm's future direction is tied to that of the vendor. The decision of whether to outsource should be based on the interdependence of the outsourced function with other internal processes. Companies should not outsource such highly integrated functions, particularly when high adaptation with the vendor or supplier is required.

As you can see, outsourcing isn't always the right decision. Before turning to outside vendors a company should always be clear on its source of competitive advantage and not outsource that aspect of its operation. Interestingly, for a number of companies, manufacturing is not seen as a strategic function and they choose to outsource it. Examples of this are provided by Cisco in the electronics industry and Nike in footwear. These companies outsource all aspects of manufacturing. Almost all industries, however, use third-party logistics providers for delivery, transportation, warehousing, and other logistics services. In fact, the role of third-party logistics providers has been increasing to include activities such as final packaging, software loading, and even final assembly.

CUSTOMER SERVICE STRATEGY

Customer service is extremely important as it is about bringing value to the customer. Consequently, the mechanism by which this is achieved is a key building block of SCM strategy. The customer service strategy of a company should be based first on the overall volume and profitability of market segments. The company then must understand what the customers in each segment want and make a decision as to how the company is going to meet the demands of its customers. Typically this requires dividing the market by volume and profitability. This is shown in Figure 2.5.

MANAGERIAL INSIGHTS BOX—OUTSOURCING ALLIANCES

Li & Fung Ltd.

In early 2010, Wal-Mart announced that they were forming a strategic alliance with Li & Fung Ltd., a supply chain giant based out of Hong Kong. Li & Fung is known as an intermediary between retailers and manufacturers, especially those wishing to do business in China. Founded in southern China a century ago, Li& Fung does not own any factories or equipment but orchestrates a network of 12,000 suppliers in 40 countries. It sources goods for numerous retailers including The Limited, Walt Disney, Kate Spade, and Target Corporation. In 2008, Li & Fung had a turnover of $14 billion, indicating the sheer volume of their business. So, what benefit could Wal-Mart gain from the alliance?

The alliance is expected to provide benefits to both companies, each taking advantage of the other's strength. Wal-Mart expects to benefit by consolidating a part of its multibillion-dollar sourcing portfolio that supplies the goods it sells in stores. In addition, Wal-Mart will have access to all of Li & Fung's global connections and leverage as a huge purchaser, and is hoping that the alliance will accelerate its international growth. In turn, Li & Fung is hoping to expand beyond its core sourcing operations and move into higher-margin businesses such as retailing and brand licensing. In addition, it is hoping the alliance with the retail giant will significantly contribute to its financial position.

“Wal-Mart has obviously figured out that Li & Fung can do certain things more cheaply than Wal-Mart can, making this a good move for them,” said Patricia Edwards, principal and retail analyst at Storehouse Partners. “You now have a dedicated global player working on a big scale with a global retailer, instead of a retailer's buying operation that may not have been totally integrated.”

Entering into such an alliance demonstrates that Wal-Mart understands its sourcing strategy and that using an “expert” to source on a large global scale makes good business sense. This is an excellent example of advantages that outsourcing alliances can provide.

Adapted from: “Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. Announces Strategic Alliance with Li & Fung Limited.” January 28, 2010. www.reuters.com

Some market segments will be small in volume and low in profit, and pursuing them may not be worthwhile. At the other extreme are market segments that are high in volume and profitability which are highly desirable. The other two segments, low volume high profit and high profit low volume, are segments the company needs to closely evaluate and make a decision that prioritizes resources giving priority to the top right-hand quadrant.

In developing a customer service strategy, companies need to make decisions such as whether all customers need to get same-day delivery or whether different service levels should be designed depending on the importance of the customer. A related decision is whether all products should be equally available to all customers. A company may decide that some customers should have quicker access than others. For example, Delta Airlines, as most airlines, has two separate customer service lines: one for regular customers and one for “platinum” customers. Although the transactions received are the same on both lines, customers that call on the “platinum” line absolutely never have to wait for a customer service representative and receive more prompt service overall.

FIGURE 2.5 Market segmentation based on volume and profitability.

It is important to keep in mind that not all customers need, or even want, the same level of service. Therefore, it is critical for a company to know exactly which customers want which type of service and identify the high-value customers. For example, in the computer industry many commercial customers may not care as much about price as they do about customer service help support that provides rapid problem resolution. In the personal computer market, however, customers care more about price. A good strategy here is to segment the market and provide different service help support for the different market segments. High customer service is costly and it should not be wasted on market segments that do not place value on it.

This means that companies need to segment the market carefully and consider how to effectively meet demands of those segments. The implications for supply chain management strategy is that there may be different supply chains for different market segments.

SUPPLY CHAIN STRATEGIC DESIGN

Companies often do not give much thought to the design of their supply chains. They often focus on cost reduction through low cost purchasing, manufacturing, or logistics. This can translate into supply chains that do not necessarily support the overall business strategy. In the previous section we discussed the building blocks of supply chain strategy. We now address the strategic design of the supply chain and the overriding criteria that must drive its development.

The way a company competes in the marketplace is called a competitive priority. Supply chain strategy and supply chain design greatly depend on a company's competitive priorities. The companies that follow this process—companies like Dell, Wal-Mart, Toyota, and IBM—have been very successful. Unfortunately, too many companies just mimic others in their industry and create supply chains that look just like that of their competitors. This does not lead to a strong competitive advantage—it simply leads to being a follower in one's industry.

There are five primary competitive priorities:

- Cost

- Time

- Innovation

- Quality

- Service

Let's look at each of these competitive priorities and show how each results in differing strategic supply chain designs.

COMPETING ON COST

If the company's business strategy is to compete on cost, then the supply chain strategy must be designed to support this. Companies that compete on cost offer products at the lowest price possible. These companies are either maintaining market share in a commodity market, or they are offering low prices to attract cost-sensitive buyers. Once a company's business strategy has determined that the company will compete on cost, the other functional strategies—including the supply chain strategy—should be designed to support this.

For example, competing on cost requires highly efficient, integrated operations that have cut costs out of the system. The supply chain plays a critical role in keeping both product and supply chain costs down. It may also require going to the least-expensive suppliers rather than focusing on high quality components. The low-cost supply chain focuses on meeting efficiency-based metrics such as asset utilization, inventory days of supply, product costs, and total supply chain costs. The operation strategy is designed for product and process standardization, as are operations of the suppliers. Notice that the supply chain design would be different had the chosen business strategy focused on something else, such as competing on customization. In that case, cost would be less of an issue as would be the ability to provide a wide range of customized products.

Although Dell Computer Corporation has been a model of supply chain excellence, Dell does not compete on cost. In fact, Dell does not claim to offer the least expensive computers, but merely customized computers in record time. That is the major difference. Dell's computer prices are within the industry range. This is unlike Wal-Mart that promises the lowest prices but not special customized products. The important thing is that each company's supply chain is designed to support the chosen business strategy.

Although efficiency and low cost are hallmarks of excellence, they cannot be achieved at the expense of service, innovation, or quality, if one of these is an element of the business strategy. An example of this is the apparel industry where manufacturers typically outsource production to Southeast Asia. The manufacturers insist on fixed production schedules to keep their costs low. This, however, impacts their flexibility and can hurt retailers when demands unexpectedly shift, such as when there is an unexpected surge of demand. This limits retailers in their ability to respond to demand. For many retailers being out of stock on a regular basis can play havoc with customers and erode market share. Focusing on price alone, without considering other aspects of the business strategy may result in a poor supply chain strategy.

COMPETING ON TIME

Time is one of the most important ways companies compete today. Companies in all industries are competing to deliver high quality products in as short a time as possible. FedEx, LensCrafters, United Parcel Service (UPS), and Dell Computer Corporation are all examples of companies that compete on time. Customers today are increasingly demanding short lead times and are not willing to wait for products and services. Companies that can meet needs of customers who want fast service are becoming leaders in their respective industries.

Making time a competitive priority means competing based on all time related dimensions, such as rapid-delivery and on-time delivery. Rapid delivery refers to how quickly an order is received; on time delivery refers to the number of times deliveries are made on time. When time is a competitive priority, the job of the operations function is to critically analyze the system and combine or eliminate processes in order to save time. Companies can use technology to speed up processes or they can rely on flexible workforce to meet peak demand periods, and eliminate unnecessary steps in the production process.

FedEx is an example of a company that has chosen to compete on time. The company's slogan is that it will “absolutely, positively” deliver packages on time. To support this business strategy, the entire supply chain has been set up to support this criteria. Bar code technology is used to speed up processing and handling, and the company has discovered that it can provide faster service by using its own fleet of airplanes. This technology has enabled FedEx to compete on time, but it is costly. Consequently, FedEx neither competes on cost nor does it make any claims regarding its prices. Its business strategy is to compete on time, and all the other functions are aligned to support this strategy.

COMPETING ON INNOVATION

Companies whose primary strategy is innovation focus on developing products that the customers perceive as “must have” and thereby pull the product through the supply chain with significant demand. Examples of such companies include Sony and Nike—companies that deliver innovative products customers want. Due to the “must have” nature of these products, these companies can typically command a premium price, which is their advantage because competing on innovation requires a sizable financial commitment. In addition to the supply chain capability, the real ability to compete on this dimension lies in superior marketing and product development, which is directly related to the supply chain.

Companies that compete on innovation typically have a very short window of opportunity before the imitators enter the market and begin to steal market share. Companies competing on innovation are aware that they must enter the market early with an innovative design. The supply chains of these companies typically focus on two features: speed and product design. This requires a carefully integrated supply chain that enables collaboration on product design between suppliers and manufacturers. Manufacturers with this type of supply chain have to have both internal integration between functions and be integrated externally with suppliers.

Another challenge for innovative supply chains is the ability to quickly raise production volumes should demand suddenly increase. An innovative product doesn't accomplish much if the company cannot quickly deliver a large volume of the product to the market to meet demand. Often this cannot be accomplished by one company's manufacturing process alone and the ability to access production capacity when needed provides a significant competitive advantage. That is why most of these companies, such as Nike, are “virtual companies.” This means that marketing and product design are their strength, yet they outsource all the other aspects of their supply chain and manufacturing processes, albeit through a tightly controlled system.

COMPETING ON QUALITY

Competing on quality means that a company's products and services are known for their premium nature. An important part of this competitive priority are issues of consistency and reliability. Examples of companies known for competing on quality are Mercedes, General Electric, and Motorola. There are many aspects of the supply chain that are altered when companies compete on quality versus another dimension, such as cost. This includes sourcing of components, as well as the implementation of concepts such as total quality management (TQM) and Six Sigma throughout the entire supply chain. This means embedding quality in all aspects of transportation, delivery, and packaging. This is particularly challenging when items are perishable, fragile or of high value, such as luxury goods.

As supply chain management is a boundary-spanning, an important attribute of competing on quality is product traceability. This means that the supply chain has the ability to easily trace a product from point of origin in the supply chain, through to the customer, and back down the supply chain in the case of returns. This feature is increasingly becoming important with greater emphasis on security and sustainability. Radio frequency identification (RFID) tags have provided excellent product traceability. Consider industries where this might be of particular importance, such as the pharmaceutical industry where safety is critical. Another industry is the area of luxury goods where counterfeiting is a problem and traceability is very important in the identification of goods.

Barlean's Organic Oils

Barlean's Organic Oils provides an example of a company that competes on quality and has designed a supply chain to support this strategy. Barlean's is a company that sells health supplements, but it is most known for its flaxseed oil. In fact, Barlean's is a sales leader in the market for flaxseed oil. The business strategy of Barlean's is to focus on quality and freshness. The company maintains a four-month expiration date where competing products may be five months old even before they get to the retail shelf. It is the manufacturing and distribution processes that give Barlean's its edge. Typical competitors have manufacturing processes that expose the flax seeds to heat, light, air, and overprocessing, all of which reduce the potency of the flax seeds. In contrast, Barlean's starts with organic flax seeds and has a system where the seeds are protected from the elements. The seeds are not pressed until an order has already come in from the retailer. Barlean's uses an express mail system for shipping orders to expedite arrival at the retailer. Although this is a more expensive alternative, it is one that supports the company's commitment to quality.

Adapted from: Cohen, Shoshanah and Joseph Roussel. Strategic Supply Chain Management. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Company, 2005: 25–26.

COMPETING ON SERVICE

Competing on service means that a company understands the dimensions that its target customers define as high service and has chosen to tailor their products to meet those specific needs. An important aspect of this strategy is that these companies typically build customer loyalty, which can often guarantee continued sales. These companies typically have exceptional order fulfillment systems, with fast invoicing that enables them to be consistent and reliable. These companies typically do not compete on cost and cannot offer the lowest-priced product. However, their target market is one that wants high-quality service and is willing to pay the extra cost.

From an operational viewpoint, companies with superior customer service often avoid unnecessary costs related to expediting orders or the costs of product returns, often faced by other companies. These companies also have a strong ability to segment their customer based on perceived value. This way they can offer services of one type to one market and a modified version to another. For these firms, the relationship between product cost and profitability is well defined. Consequently, highly customized services that are costly to deliver are only offered for customers who meet strict business criteria and tend to be in the high-value segment.

WHY NOT COMPETE ON ALL DIMENSIONS?

Successful companies understand that they cannot effectively compete on all dimensions, as they cannot be all things to all people. This is a very important and difficult point for most companies as they typically want to be good at everything. The companies that succeed are those that understand which dimensions to excel on and are able to focus their energies on those dimensions. This does not mean that a company will have poor performance on the other dimensions. In fact, companies have to continually trade off one competitive dimension for another. However, this means that a company should have merely satisfactory performance, or stay within the norms of the industry, on those strategically less important dimensions.

Two important concepts that companies need to monitor are order winners and order qualifiers. Order winners are those characteristics that win the company orders in the marketplace. Order qualifiers are those characteristics that will qualify the company to be a participant in a particular market. This means that a company just needs to stay within the industry standard on its order qualifiers to ensure that it is on par with competitors. However, when it comes to order winners—that is where it should excel.

Recall that a supply chain must be designed to support the business strategy, so alignment between the two should be a top priority. It should be remembered, however, that strategy is a dynamic rather than a static process. As such, strategies change over time and supply chains must adapt accordingly.

STRATEGIC CONSIDERATIONS

SMALL VERSUS LARGE FIRMS

When developing a supply chain strategy it is important to understand the company's strengths and weaknesses, in order to realistically determine what it can and cannot accomplish. The company must play to its strength.

For many supply chain companies, a large source of power comes from their sheer size. Companies like Wal-Mart, Toyota, and Home Depot are large firms with equally large market clout. These companies are sometimes called “supply chain masters” and have the ability to “strong-arm” their suppliers into compliance. However, not all companies have this advantage.

When designing its supply chain strategy, a company needs to understand how much influence or power it has in the marketplace. Large companies have the advantage of being able to buy larger quantities of goods and command lower prices due to quantity discounts. Due to their size, these companies can impose their own processes and rules on suppliers and customers.

Large companies can also impose the supply chain structure they want. They can impose their own process rules on suppliers and maintain a high degree of control over the entire supply chain. In the auto industry, for example, manufacturers stipulate that if a supplier's delay in delivery shuts down the production line, the supplier can be subject to a substantial penalty due to revenue lost while the line is down. Not every company can make this kind of demand.

Smaller companies have, however, developed their own supply chain strategies. For example, when developing their supply chain strategies smaller companies should consider that size is relative. Few companies are large on a broad, global scale. When the scope narrows to a particular market segment or region, companies can find that they are really not that small. In that case, they can find select suppliers within that market segment with whom to work with and develop strategies to compete within that market. Also, smaller suppliers can create cooperatives to aggregate their power.

SUPPLY CHAIN ADAPTABILITY

Successful companies understand that change is a natural part of the business environment and adapt their supply chains in anticipation. As market and environmental conditions shift, new products emerge, and new technology is developed, business strategies need to change. A company's supply chain strategy must quickly adapt to stay in sync with the business strategy. Consequently, the supply chain strategy must be adaptive.

The rate of change and the need for responsiveness, however, vary by industry. Some industries experience frequent and constant change, as seen in the personal computer industry. In this industry, companies need to change constantly such as selling through the Internet, exploring new distribution channels, or moving to an assemble-to-order strategy. In other industries, however, change can take much longer. One example of this is the aerospace industry, where changes in the supply chain typically occur after many years.

There are a numerous factors that can require significant adaptability on the part of a company's supply chain. One of these is the development of a new technology that can change a business and its industry. The Internet is a good example, which created a direct link between businesses and customers. Companies such as Amazon, Dell, and many others could now sell directly to customers and cut out distributors. The Internet completely changed the “rules of the game” for the business community and required companies to quickly adapt their supply chains.

Another factor that requires supply chain adaptability is a change in the scope of a company's business. Any time a company offers new products or services, targets new markets, or expands geographically, it needs to completely rethink its supply chain strategy. The reason is that the company may likely need to expand its manufacturing capacity, add new distribution capabilities, develop new channels, or find new suppliers. Any time the scope of the business changes, the supply chain needs to adapt.

Although these events require adaptability, creating and implementing a supply chain strategy is a dynamic process that should be done on a continual basis. It is not an annual or bi-annual event. Any change in a company's competitive position—a new competitor entering the market, a shift in the market or competitive strategy—should automatically result in a reassessment of the company's supply chain strategy.

PRODUCTIVITY AS A MEASURE OF COMPETITIVENESS

The purpose of supply chain strategy is to provide higher competitiveness to firms. Being able to measure competitiveness provides a scorecard for companies to evaluate how they are doing. One of the most common measures of competitiveness is productivity. We now look at its computation and interpretation.

MEASURING PRODUCTIVITY

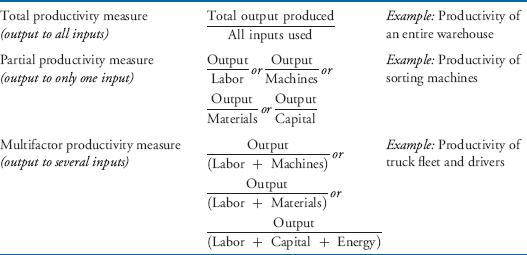

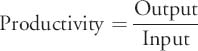

Productivity is a measure of how well a company uses its resources. It is computed as a ratio of outputs to inputs, where the inputs can be labor or materials and outputs can be goods and services.

FIGURE 2.6 Productivity Measures.

The productivity measure can be used to measure performance of an individual resource, such workers or machines. It can also be used to measure performance of the entire organization such as a warehouse, an entire supply chain, or even a nation. This is shown in Figure 2.6.

Total productivity is used when we want to measure utilization of all resources combined, such as labor, machines, and capital. Let's say that a dry-cleaning company has monthly dollar value of outputs worth $18,000. This includes all items dry-cleaned for customers. Let's also say that the value of its inputs, such as labor, materials, and capital, is $9,000. The company's total monthly productivity would be computed as follows:

![]()

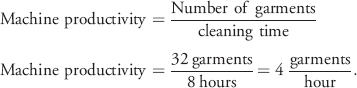

If the company wanted to compute the productivity of its machines it would use a partial productivity measure. Say that its machines can clean 32 garments in eight hours, their productivity would be computed as follows:

INTERPRETING PRODUCTIVITY

The more efficiently a company uses its resources the more productive it is and, therefore, the higher the productivity ratio. However, interpreting productivity is more complicated than it may appear.

Consider the numbers we just computed, such as a machine productivity of four garments per hour. Does that number mean anything to you? The answer is no. The reason is that in order to interpret the meaning of a productivity measure, it must be compared against a baseline. For example, if we know that a competing dry-cleaner has a machine productivity of six garments per hour then the productivity number we just computed—four garments per hour—tells us that our productivity is low. For our competitor, however, this is good news as their productivity is higher and suggests that they are more competitive.

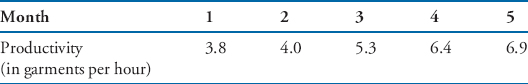

In addition to benchmarking productivity measures against others, productivity should be measured over time to observe changes. Let's say that our dry-cleaner chose to track machine productivity on a monthly basis and had chosen to purchase new machines in the third month. Perhaps the following is observed:

Now we can see that productivity had gone up after the purchase of the new machines. However, productivity continued to grow perhaps as the workers adjust to using the new equipment. Looking at productivity over time provides a very different level of understanding than looking at just one number. The best alternative is to track productivity over time and benchmark against industry standards.

When computing productivity it is important to consider the units used in its computation as they provide different meanings. Consider a restaurant that measures productivity as either a ratio of customer service to labor-hour versus customer serviced to square footage. The first measure looks at utilization of labor, whereas the second measure looks at utilization of space. One consideration is how a company competes in the marketplace. For example, a company that competes on speed would probably measure productivity in units produced over time. However, a company that competes on cost might measure productivity in terms of costs of inputs such as labor, materials, and overhead. Well-chosen units can make productivity a useful metric for evaluating competitiveness over time.

CHAPTER HIGHLIGHTS

- Supply chain strategy is a long-range plan for the design and ongoing management of the supply chain to support the business strategy.

- Strategic alignment needs to exist between the business strategy and the functional strategies. A company's supply chain strategy should be developed to support the company's business strategy.

- Companies can gain a competitive advantage through either a cost-productivity advantage or a value advantage. A company with a cost-productivity advantage maintains competitiveness by offering the lowest cost product or service. A company with a value advantage maintains competiveness by providing a product with the greatest perceived differential value compared with its competitors.

- The experience curve describes the relationship between unit costs and cumulative volume, where organizational costs are reduced due to experience and learning effects that result from processing a higher volume.

- The four building blocks of supply chain strategy are operations strategy, sourcing strategy, distribution strategy, and customer service strategy.

- The way a company competes in the marketplace is called a competitive priority. The supply chain strategy and supply chain design will be different based on a company's competitive priorities.

- Competitiveness can be measured by productivity, which is a measure of how a company utilizes its resources.

KEY TERMS

- Business strategy

- Supply chain strategy

- Cost-productivity advantage

- Value advantage

- Experience curve

- Value segments

- Operation strategy

- Product positioning strategy

- Distribution strategy

- Sourcing strategy

- Loss of control

- Dependency risk

- Competitive priority

- Product traceability

- Order winners

- Order qualifiers

- Supply chain masters

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- Find an example of a company whose product you like. Identify its business strategy and its supply chain strategy. Explain whether or not the supply chain strategy supports the business strategy.

- Identify ways a company can move from a “commodity” position to one of a cost and/or value advantage. Is a commodity position always bad and how can companies differentiate themselves in this position?

- Explain the differences between vertical integration and outsourcing. Identify the strategic advantages of each and explain how each position can be used to help supply chain strategy.

- Provide business examples of the three operations strategies: make-to-stock, assemble-to-order, and make-to-order. Explain what it would take for a company to move from a make-to-stock strategy to make-to-order, and vice versa. What are the advantages and disadvantages of each strategy?

- Provide business examples of companies that compete on each one of the identified competitive priorities. Explain how their supply chain strategies are different based on their specific competitive priority. Select one of the business examples you provided and explain how the company would need to change its supply chain strategy if it shifted its competitive priority.

PROBLEMS

- Mario's Pizzeria is a local pizza shop. Mario is trying to evaluate the productivity of his operation. One worker can make approximately three pizzas in 30 minutes, whereas another four pizzas in 20 minutes. Which worker is more productive?

- An automated packaging machine used in warehousing can sort and pack six large boxes in 15 minutes. A new machine that is being considered can sort and pack four boxes in 8 minutes. How much more productive is the new machine?

- The diagnostic department at Saints Memorial Hospital provides medical tests and evaluations for patients, ranging from analyzing blood samples to performing magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Average cost to patients is $60 per patient. Labor costs average $15 per patient, materials costs are $20 per patient, and overhead costs are averaged at $20 per patient.

- What is the multifactor productivity ratio for the diagnostic department? What does this finding mean?

- If the average lab worker spends three hours for each patient, what is the labor productivity ratio?

CASE STUDY: SURPLUS STYLES

Surplus Styles is a manufacturer of hair care products, including shampoos, conditioners, and hair gels. The company, located in Southern California, bottles the shampoos and other various hair products in their manufacturing plant, but sources the content from a number of chemical suppliers. The company has historically competed on cost and has used competitive bidding to select suppliers and award yearlong contracts. The Director of Sourcing, Derick M. Frizzle, has managed the competitive bid process for the past 10 years, having moved up the ranks from purchasing. He was particularly proud that the company was cost-competitive in its market segment.

One recent day the president of the company, Frederick Davenport, called for a meeting with Mr. Frizzle. Derick could tell from the tone of Davenport's message that the meeting would be accompanied by less-than-stellar news. As Derick took the infamous ride up the wood-paneled elevator with green marble floors to the top of their office building, he contemplated what he could have possibly done wrong. He had followed the same type of supplier bidding process for years and the company was doing well financially. He was anxious to hear what Davenport had to say.

Derick entered Davenport's vast office, a room highlighted by ceiling-to-floor windows. He could see Mr. Davenport sitting at the end of the long, dark wooden table, with each one of his two aides accompanying him on each side. The man on the right was Bo Jenson and the woman on the left was Gertude Masterson; neither were taken lightly within the company. Derick could always tell when it was going to be a bad day.

“Darn hippies,” Davenport rumbled. “Bo and Gertude have some troubling news. This swing towards animal rights and ‘quality goods’ is about to cost me a lot of money,” Davenport continued, making mocking “bunny ears” with his bulbous index and middle fingers. “Apparently market trends are changing again and not for the better.” Davenport continued to explain that there was going to be a change in the competitive strategy of the firm. The competition in the hair care market had become fierce and there was greater focus on quality. Specifically, the recent trend in animal rights and natural, organic products meant ensuring that the shampoo content did not go through animal testing and that it was ensured to be hypoallergenic. The current products were produced to compete for price and did not agree with the new demands. Davenport wanted to see products on the retail shelf with this quality standard as soon as possible. “Do it,” Davenport continued and sat back down. This concluded the meeting. Luckily Mr. Frizzle had an easy exit as he had only gotten one foot in the door before his task was demanded.

Derick M. Frizzle was rather pleased with his new detail as he cared greatly for nature and had always refrained from purchasing his own company's products due to their lack of consideration for both the individual and the environment. However, Derick was now confronted with a problem. His current suppliers offered the lowest cost in the business and would likely not be able to provide the needed quality assurances. His expertise had been in procuring the least expensive ingredients available and he did not know where to begin changing his sourcing practices.

CASE QUESTIONS

- Identify the steps that Derick should take to solve his problem.

- Should Derick ask for the required changes from the current suppliers? If they do not comply, should he solicit new suppliers? How might he do this?

- Should Derick go through a competitive bid in the future? If so, should he do it for all purchased products or just some products?

- What are the differences when looking for suppliers to meet cost standards versus quality standards?

REFERENCES

Cohen, Shoshanah, and Joseph Roussel. Strategic Supply Chain Management. New York: McGraw-Hill Company, 2005.

Lambert, Douglas M., and A. Michael Knemeyer. “We're in this Together.” Harvard Business Review, December 2004: 114–122.

Sengupta, Sumantra. “The Top Ten Supply Chain Mistakes.” Supply Chain Management Review, July–August 2004: 42–49.

Takeuchi, Hirotaka, Emi Osono, and Norihiko Shumizu. “The Contradictions that Drive Toyota's Success.” Harvard Business Review, June 2008: 96–105.