6 Sustaining Local Livelihoods Through Coastal Fisheries In Kenya

George N. Morara, Farida Hassan and Melckzedeck K. Osore

6.1 Introduction

As the human population is rapidly growing along the Kenyan coast, demand for food security and local livelihoods for the coastal inhabitants will continue increasing, thus accelerate the pressure on coastal and marine resources including the fisheries. This situation is relevant to debate on sustainable development which is the present concern across the globe (WCED, 1987; Pezzey, 1989). However, context specific choices have to be made on what would constitute indicators of sustainability, as this subject is still argued differently across the disciplines such as, ecology, economics, sociology, development and political studies (De Wit and Blignaut, 2000). In this chapter, attempt is made to highlight some of the approaches currently used in Kenya to sustain local livelihoods through coastal fisheries. Some of the key indicators which have been used to monitor sustainability in fisheries management and livelihood development along the coast are discussed. The perspective of capital theory approach to sustainable development is reviewed and found useful for consideration in future selection of sustainability indicators.

6.1.1 Overview Of Global Fisheries Status

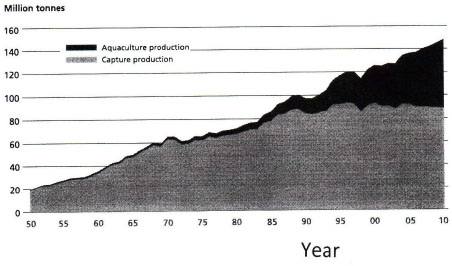

In the ancient years of global fisheries development, traditional fishing processes were somewhat limited in technology, geographic expansion and target species. In that situation, coupled with relatively low human populations, it was possible to find large proportions of naturally protected fish populations with the majority distributed outside the targeted fishing areas. However, with industrialization of fishing processes and increased efficiency in capturing target species, a steady growth in global fisheries production was observed between 1950 and the mid-1990s, but slowed in the later years of the 90s according to the records with Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO, 2012). This fact may be attributed to enhanced depletion effect on the natural fisheries resources. On the other hand, high food demands of the world’s population, which is currently estimated at about one billion people (FAO, 2012) has necessitated intensified effort to increase fish production from aquaculture systems.

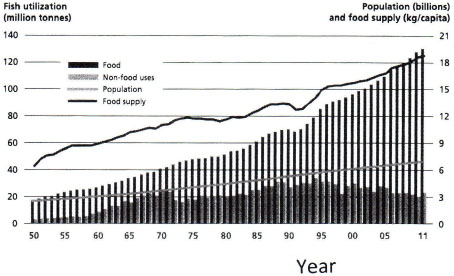

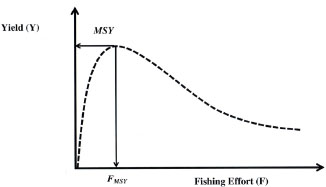

The recent changes in world fish production and utilization trends presented in Fig. 1 and 2 respectively may imply the pressing demand for food and nutrition needs of the fast growing world human population, against finite natural resources, need concerted efforts by the global community in addressing the sustainability of fisheries from the perspective of both production and local livelihoods. Today, sustainable fisheries management has become a common discourse in many fisheries governance systems. Theoretical fisheries models have been constructed and applied in different contexts to help in designing fisheries management programmes for both underexploited and overexploited fisheries. A classic example of single-species fish population models which has been widely used as an indicator of sustainability in fisheries science and management is the maximum sustainable yield (MSY), described by Pauly et al. (2002) and Mace (2001). Fundamentally, this is a surplus production model which underpins the notion of sustainable harvesting and whose objective is to encourage managers to maintain a fish population size at the point of maximum growth rate. The model gives a perspective of the entire fish stock, fishing effort and the total yield obtained during a specified fishing period. Thus, it assumes that a fishery may be maintained at maximum growth rate by harvesting fish individuals recruited into the population while allowing indefinite reproduction. The fishing effort at which the maximum sustainable yield is achieved is called optimal fishing effort (FMSY)

Figure 1: World capture fisheries and aquaculture production (FAO, 2012).

Figure 2: World fish utilization and supply (FAO, 2012).

Figure 3: Illustration of a typical MSY model for fish stock assessment and fisheries management (Adapted from Sparre and Venema 1992).

Fig. 3 illustrates a typical MSY and optimal fishing effort (FMSY) concept as applied in fish stock assessment and fisheries management approaches (Sparre and Venema, 1992).

Calculation of MSY takes into consideration the fishing pressure or fishing rate expressed as fishing mortality rate (F) and the total catch or yield which is expressed as (Y) within a fishing period. Hence the input data for MSY are:

- 1. F (i) = (effort in year i, i = 1, 2,……………,n)

- 2. Y/f = yield (catch in weight) per unit of effort in year i.

Sparres and Venema (1992) discuss that the Y/f may be derived from the yield of a fishery, say Y(i) of year i and the corresponding effort, f(i). The MSY is thus derived from a linear model suggested by Schaefer (1954) in which the yield per unit of effort (Y/f) is expressed as a function of the fishing effort (f) as below:

Y(i)/f(i) = a +b*f(i) if f(i) ≤ -a/b

In the above equation, a and b are parameters determined from a regression of the yield per unit of effort (Y/f) against the corresponding effort. Thus, b represents the slope of the equation while a is the y-intercept of the slope. Implicitly, the values of these parameters can be calculated when the amount of fishing effort in a fishery and the amount of yield at various levels of fishing efforts are known. Apart from the Schaefer model, other empirical formulas have been developed to provide a rough estimate of MSY in various instances where challenges of obtaining fisheries data exist. Some example of such formulas include the Gulland’s formula (Gulland, 1971); Cadima’s formula (Troadec, 1977); and other models by Garcia et al (1989).

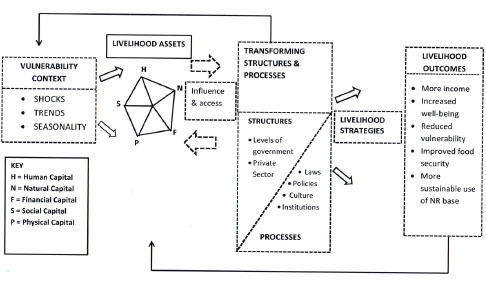

Figure 4: The Sustainability Rural Livelihood Framework (Adapted from Carney, 1998).

Essentially, estimating the MSY values for exploited fisheries requires substantial amount of human capacity and time to ensure collection of accurate data. Therefore many government agencies mandated to manage fisheries resources are often trapped in rigorous assignments of collecting data and analysing the MSY values without adequate regard of the need to monitor and evaluate the relevance of such data or other external factors which often undermine fisheries restoration and sustainability (Mace, 2001). Despite the existing wide knowledge on threats to the global fisheries, and the effort made towards restoration of fishery resources e.g. the Earth Summit of Johannesburg, overfishing still persists in many part of the world’s fishing areas (Rosenberg, 2003). In fact, this may explain the basis on which the MSY concept has been criticized for being less robust in fostering a holistic fisheries management approach and blamed for drastic collapse of fisheries in many regions across the world (Larkin, 1977; Walters and Maguire, 1996). It is largely theoretical and ignores in its computation many other factors that influence fisheries. For example, factors such as environmental degradation, age and size of the species in question as well as the effect of by-catch tend to be discounted. As a result, many fisheries governance systems are somewhat sceptical about reliability of using a computerized MSY as a sustainability indicator.

6.1.2 Paradigm Shift In Fisheries Management And Sustainability Indicators

Since the early 1990s, new paradigms have evolved focusing on Ecosystem Based Management (EBM) systems for fisheries and forestry and other natural resources (Slocombe, 1993; Slocombe, 1998). The concept of ecosystem-based management takes into consideration an array of the possible interactions within an ecosystem. It has the feasibility of integrating both anthropogenic and ecological factors into a management framework rather than focussing on single species or ecosystem services in isolation (Levin and Lubchenco, 2008). For instance, on the global scale, it is undisputed that the major threats to most of the coastal and marine fisheries are not only rooted in overfishing, but also the disruption of their marine ecosystems due to chemical pollution, nutrient enrichment and climate change among other factors. Therefore, under such circumstances, a realistic indicator of sustainable fisheries should strive to interrogate both ecological and anthropogenic roles in fisheries dynamics. This is consistent with the recommendations of Pauly et al (2002) that since single species assessment models have not served fisheries managers well, they should be complemented with elements drawn from the species ecology and lessons learnt from efforts of limiting fish mortality.

Notably, some advances have been made towards the implementation of EBM. In the context of fisheries management, the concept of ecosystem-based fisheries management (EBFM) has been discussed widely and recommended for adoption (Allison and Ellis, 2001; Christie et al., 2007; Metcalf et al., 2009). Under the EBM framework, it is acknowledged that all fishing activities have inherent and immense impacts on fish abundance, trophic structure of aquatic ecosystems, biodiversity status and most importantly, the long-standing human interactions (Christie et al., 2007). Hence, sustaining fisheries is given equal importance as the local livelihoods which depend on them. This is because both are linked to food security, employment opportunities and economic development at local, regional and national levels.

Contemporary fisheries management embraces EBFM by integrating fisheries with livelihood and sustainability issues. While such efforts are more advanced in the developed countries, they are still in their early stages in third world and developing countries. For example, in Africa today, several donor supported projects are developed with the aim of striking a balance between local livelihoods and fisheries conservation strategies. This reflects a departure from the outdated and top-bottom enforcement of legislative measures which largely disregard the interests of people who are often affected directly or indirectly by the same measures. Involvement of ‘local actors’ or multiple stakeholders in fisheries management can create a winwin situation and inculcate democratic decision making processes in the fisheries governance systems. An example from West Africa is the case of the Sustainable Fisheries Livelihood Programme in which 25 countries in the region were involved in implementing the concept of Sustainable Livelihood Approach (SLA) to fisheries management (Allison and Ellis, 2001; Allison and Horemans, 2006). The concept was successful in aligning fisheries policies with poverty reduction initiatives, and to a large extent helped in identifying ways of reducing fishing pressure on fully exploited or over-exploited fisheries.

Lessons and experience from the SLA may help to understand the vulnerability of small-scale fisheries and outstanding threats to local livelihoods of artisanal fishers. Vulnerability in this context refers to the high degree of exposure to a devastating shock, risk, stress or food insecurity that may threaten life (Chambers, 1989; Davies, 1996; Allison and Ellis 2001). The factors that may expose livelihoods to such risks include, but are not limited to, environmental stress such as climate change, pollution and habitat degradation, over-exploitation of a resource, and inappropriate legislations. Communities who become resilient to such circumstances are those whose livelihoods have been diversified rather than depending solely on natural resources (Allison and Ellis, 2001).

Knutsson (2006) argues in favour of the SLA applications as appropriate and trans-disciplinary on the basis that this approach is produced, disseminated and applied across the borders of research, policy and practice in resource management. Furthermore, this being a newly emerging field with a significant focus on the human ecology, the approach would be more practical and useful if tools for identification and evaluation of sustainability indicators were provided. Knutsson (2006) thus endeavours to provide this missing knowledge by assessing a set of criteria for integrative approaches to sustainable development problems in the context of SLA.

Other approaches similar to SLA and widely discussed in literature include the Sustainable Rural Livelihood (SRL) a framework which was originally provided in Carney (1998). The SRL was later elaborated in other context specific articles that have attested the linkages between natural resources and livelihoods (Scoones, 1998; Carney et al. 1999). The work of Carney (1998) provides a framework for researchers and managers to interrogate the many complex options of livelihoods development and their interaction with the environmental, economic and political processes. The framework identifies five typical assets of livelihood which may be influenced to trigger a situation of livelihood vulnerability or resilience with positive outcomes. The five assets are: the human capital; natural capital; financial capital; social capital; and physical capital (Fig.4).

From literature review, it can be inferred that these assets are implicitly embodied in the concept Capital Theory Approach (CTA) to sustainable development, which is discussed extensively by Stern (1997) and De Wit and Blignaut (2000). The literature shows that, the application of CTA still requires policy makers to have clear understanding of what constitutes the man-made and natural capital stocks in the context of sustainable development. However, emerging from the discourse objectives and indicators of sustainable development can be anchored on either the environmental or ecological point of view. In the case of environmental approach, substitutability between man-made and natural capital is favoured with the assumption that the overall capital stock will be maintained over a period of time. This approach is also described as the weak sustainability (Stern, 1997; De Wit and Blignaut, 2000). The contrast to this is the ecological approach or strong sustainability, which argues for complementarity of the man-made and natural capital with assumptions that specific capital stocks will be maintained intact over time (Blignaut and De Wit, 1999).

De Wit and Blignaut (2000) contend that the main point of argument with regard to the CTA is on the vagueness of the concept and its inadequacy in accounting for the main elements of sustainable development. However, while both the environmental economic and ecological economic approaches can be applied to maintain the capital stock over time, there is concurrence in literature that these two approaches depart with respect to the degree of capital stock substitutability for each other (Costanza, 1991; Toman, 1994; Daly, 1996; Stern, 1997). It is in this context that Stern, 1997 elaborates the major subcategories of “capital” to include aspects such as natural, manufactured, human, moral, ethical, cultural and institutional elements.

6.1.3 Sustainability In Fisheries And Livelihoods Contexts

From the previous sections, we have used the terms ‘fisheries’, ‘livelihood’ and ‘sustainability’ as the subject matter of discussion. In the following sections we attempt to contextualize the meaning of these terms and elaborate their perspectives in the coast region of Kenya, East Africa.

The term ´fisheries´ is widely applied in literature to refer to the consumptive harvesting activity of aquatic organisms from either an artificial or their natural water systems for commercial, or subsistence purposes. According to Fletcher et al. (2002), this refers to the entities engaged in raising or harvesting fish which is determined by some authority to be a fishery. Therefore, we can simplify the definition of fisheries as the union between aquatic organisms and humans in which the inherent features are the aquatic environment in a geographical region, fish populations living in that environment, human interaction with the fish population and the legal rights to engage in utilizing fish resources in specified waters or regions. In FAO (1995), fisheries management is defined as the integrated process of information gathering, analysis, planning, decision making, allocation of resources and formulation and enforcement of fishery regulations by which the fisheries management authority controls the present and future behaviours of the interested parties in the fishery, in order to ensure the continued productivity of the living resources.

In this discourse we use the term ‘livelihood’ to imply a form of support required for living or survival. From the Oxford Dictionary of English (2010), it refers to a set of activities, involving securing necessities of life (water, food, fodder, medicine, shelter, clothing) and the capacity to acquire these necessities working either individually or as a group by using endowments (both human and material) for meeting the requirements of the person and his/her household on a sustainable basis with dignity. Such set of activities are usually carried out repeatedly. According to the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Cross Crescents Societies (IFRC), a livelihood comprises people’s capabilities, assets and activities required for generating income and securing means of living (IFRC, 2010). In this regards, considerable focus is given to the people’s endowment and interaction with the available resources or opportunities such as agriculture, fisheries, forestry, mining, tourism among others. A similar definition is discussed by Ellis (2000) and Allison and Ellis (2001) who describe a livelihood as comprising three aspects namely: assets (natural, physical, human, financial and social), activities, and access to assets that is mediated by institutions and social relations.

The term sustainability is commonly used in the context of development where socio-economic and environmental objectives are highly considered. The World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) defines sustainable development as “development that meets the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (WCED 1987: pp 15). In 1988 FAO Council defined sustainability in a broader perspective to include the management and conservation of the natural resource base, and orientation of technological and institutional change to ensure the attainment of continued satisfaction of human needs for both the present and coming generations. Such sustainable development in key sectors such as agriculture, forestry and fisheries, conserves (land) water, plants and (animal) genetic resources, besides being environmentally non-degrading, technologically appropriate, economically viable and socially acceptable (FAO, 1989). The latter definition implies that considerations are given to the extent of welfare optimization from finite natural resource base with minimal resource degradation and regulated exploitation regime over time. However, it is worthwhile to note that sustainability elements can also be applied in other sectors without exploitable natural resource methods of industrial production, programmatic ideas or even governance structures.

Chambers and Conway (1991, pp:6) have elaborated the concept of sustainable rural livelihoods, that: “A livelihood comprises the capabilities, assets (stores, resources, claims and access) and activities required for a means of living: a livelihood is sustainable which can cope with and recover from stress and shocks, maintain or enhance its capabilities and assets, and provide sustainable livelihood opportunities for the next generation; and which contributes net benefits to other livelihoods at the local and global levels and in the short and long term.”

This chapter highlights some of the approaches that have been applied for sustainable management of coastal fisheries and livelihoods in Kenya. It focuses on both state and community led initiatives, especially the marine protected areas (MPAs), community conserved areas (CCAs) and co-management approach through beach management units (MBUs).

6.2 Kenya’s Marine Ecosystems And Resource Dependency

Kenya’s coastline is about 650 km long covering an area of about 83,603 km2. The coastal area is endowed with unique ecosystems with rich natural resources including marine fish, coral reefs, seagrass beds, mangrove forest and diverse cultural heritage. Almost the entire part of the coastline is covered by a fringing reef. In these areas, there are abundant populations of herbivorous fish species which maintain ecosystem balance by grazing on algae, a function which enables the corals to flourish. These ecosystems, especially the seagrass beds and mangrove forests are particularly vulnerable to overexploitation, destructive use, and the impacts associated with climate change. The high species diversity and richness, including over 250 fish species, make the marine ecosystems in Kenya areas of high protection interest. Currently, there are six designated marine protected areas (MPA) along the coast which have been designated as national parks.

The coastal region of Kenya has about 3.3 million human inhabitants. The economy of these coastal communities depends mainly on artisanal fishing, small-scale farming, livestock husbandry, subsistence forestry and small-scale businesses. Although the coastal and marine resources provide many opportunities for economic growth and reduction of poverty, their unsustainable management has contributed to degradation of the resource base as a result of high human population pressure.

6.2.1 Coastal Fisheries And Livelihoods In Kenya

Kenya’s fishery sector generally contributes about 4.7 % of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This explains the motivation of the Government to strengthen the sector through promotion of sustainable fisheries and aquaculture for improved food security and livelihood of the dependent local communities. The endowment of the coastal region with a rich fisheries resource presents myriad opportunities for economic and social transformation of the local people. Apart from this, fish provides an important source of protein for the coastal human populations.

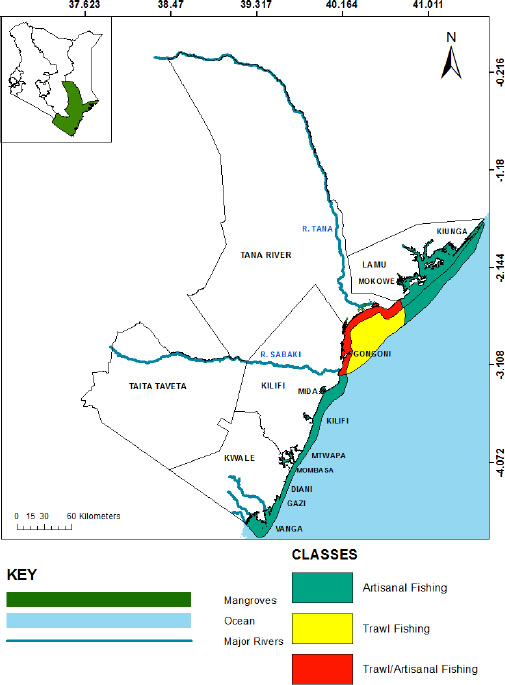

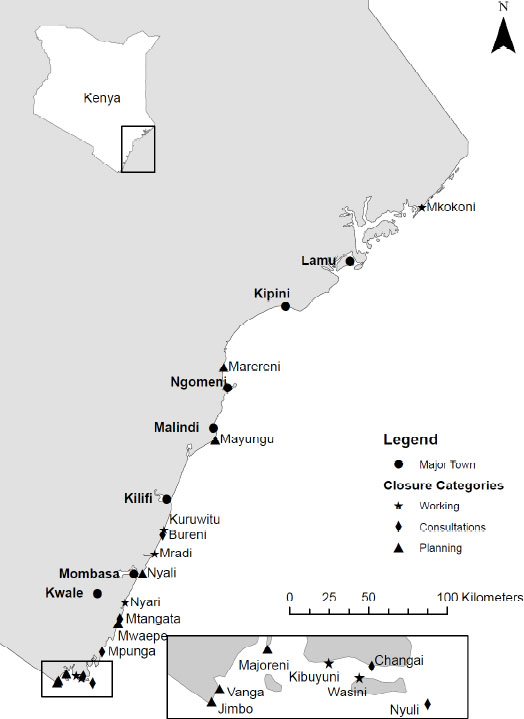

However, the Kenya coastal fishery sector is largely at artisan level and limited to the reef habitats which are currently under fishing pressure (Munga et al., 2013). The richest inshore marine fishing grounds are mostly located in Lamu Archipelago, the Ungwana Bay, North Kenya Bank, and Malindi Bank (Fig 5). The estuarine systems of the two major Kenyan rivers (Rivers Tana and Sabaki) which form the Malindi – Ungwana Bay fishing grounds, are equally very productive and support local livelihoods in the region. In the latter, commercial prawn trawling has been carried out since the 1970’s. Recent surveys by Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute (KMFRI) show that although the fishery resource in the Malindi-Ungwana Bay is under exploited, the whole fishery system is associated with high conflicts due to destructive effect of trawlers on the traditional fishing gears; competition for common resources; by-catch wastage and mistrust amongst the fisher groups (Fulanda, 2003; Munga et al., 2013).

Figure 5: A map of the Kenya coastline showing the area of artisanal and trawl fisheries (Drawn by Noah Ng’isiange, KMFRI).

Generally, Lamu Archipelago has the most productive coastal fishing area in Kenya with abundant fish populations. Its remoteness and the proximity to insecurity zone near Somalia present many logistical challenging issues, thus provide temporary protection of fish populations in the area. On the other hand a marine reserve exists in Kiunga where co-management approach has been established and works well for fishery.

Statistics from the State Department of Fisheries (a Government agency) indicate that the coastal and marine fisheries sector accounts for about 10,000 tonnes (10%) of fish of the total annual fish landings and employed approximately 13,700 fishermen by 2012 (Government of Kenya, 2012). The fishery thus supports about 60,000 people, who live near the key fish landing beaches, for their income generation and food security.

While Kenya’s coastal and marine fisheries have the potential for high offshore fisheries production, the present fisheries is largely based on a small number of demersal fish species caught by artisanal fishers who mostly operate between the shoreline and the reef. A study conducted on the species composition in landings of this artisanal fishery by Wakwabi et al. (2003) revealed domination by demersal species in the catches and trailed by echinoderms, which constitute 42% and 4% respectively (Table 1). The study observes that the most common fish species in the landings are: the rabbit fish (Siganus sutor), variegated emperor (Lethrinus variegatus), dash-dot goat fish (Parupeneus barberinus), parrot fish (Sergeant majors), sweetlips, scavenger, red snapper (Lutjanus argentimaculatus), rock cod (Plectropomus aneolatus), thumbprint emperor (Lethrinus harak), yellow goat fish (Parupeneus barberinus), peacock rock cod (Cephalopholis argus), pick handle barracuda (Sphyraena jello), sailfish and black tip kingfish. Although not all fish species in the coastal strip of Kenya have been identified, significant efforts have been made by FAO and the KMFRI staff and other fisheries scientists, to document most of the species exploited for commercial, recreational or subsistence uses. Part of this work has been documented by various authors (e.g. Glaesel, 1997; Mohammed, 2002; Anam and Mostarda, 2012).

The aerial densities of fishermen in the Kenya’s coastal reef have been estimated to range from 7-13 fishers per square kilometre (McClanahan and Kaunda-Arara, 1996). These statistics may be outdated and no recent studies have been conducted in this direction. Hence it is highly likely that the density may have increased as a result of the rapid population growth in the coastal region which has inadvertently mounted pressure on the reef fishery. It is also apparent that the current coastal fishing activities are rather chaotic and indiscriminate in species capture (Fondo, 2004). A random assessment of the fisheries from two fishing areas along the coast of Kenya conducted in 14 designated sites, 11 in Lamu (North coast) and 3 in Vanga (South coast) indicate a wide range of fishing methods employed by fishermen (Table 2). Gill nets, shark nets and beach seines are the most frequently used types of fishing gear. Commercial bottom trawl fishery is also done in 5-200 nautical miles (nM) waters as opposed to the 0-5 nM for artisanal fishery. The various gears being used have their specific merits and demerits for sustainability of the fishery. This largely depends on the sizes of the gear, the mode of operation and the specific grounds of fishing. Ring nets, for instance have been discouraged for their indiscriminate fishing effect on the fishery besides causing destruction of fishing habitats. Trawling on the other hand has serious fisheries consequences due to the high proportion of by-catch composition in the fish caught (Fulanda, 2003; Munga et al. 2013). Therefore, it is not surprising that a trawl ban was imposed in 2006 on the Malindi–Ungwana Bay due to declining fish catches and resource use conflicts that threatened livelihoods of the dependent fisher communities.

Table 1: Composition of coastal artisanal fishery in Kenya.

| Fishery category | % Composition |

| Demersal species | 42 |

| Pelagic species | 18 |

| Crustaceans | 12 |

| Sharks, Rays & similar species | 18 |

| Molluscs and Echinoderms | 4 |

| Deep sea and game fish species | 6 |

Table 2: Method of fishing commonly used in artisanal coastal fishery in Kenya.

| Fishery category | % Occurrence |

| Beach seines | 16 |

| Diving and fishing guns | 3 |

| Gill nets | 26 |

| Hook and line | 13 |

| Ring nets | 7 |

| Shark nets | 26 |

| Traps | 6 |

| Other traditional methods | 3 |

Plate 1: Artisanal coastal fishing activity using the beach seining method (Photo: Stephen Mwakiti, KMFRI).

6.3 Approaches To Sustainable Livelihoods And Coastal Fisheries In Kenya

The foregoing sections emphasize the coastal fisheries as an important resource yet it is either under-utilized, as in the case of offshore fisheries or overexploited in current situation of inshore fishery in Kenya. It is apparent that attempts to implement a sustainable livelihood approach and sustainable rural livelihood methods have not been effective in the coastal region of Kenya. Interest in participatory approaches is growing with the objectives of empowering the local communities to own and manage their fisheries. In this section, we present and discuss three practical approaches that are being used in sustaining coastal fisheries in Kenya in the light of their strength and weaknesses.

6.3.1 Establishment of Marine Protected Areas

Marine protected areas (MPAs) are highly recommended across the globe for their effectiveness in conservation and management of coastal and marine resources. In the tropical coral reef ecosystems, MPAs have served as an effective tool for maintaining biological diversity and species abundance as well as fisheries management (Kelleher, 1999; Gell and Roberts, 2003). For over four decades, Kenya has used MPAs as a conservation tool, thus established nine national and marine parks and reserves under the management of Kenya Wildlife Service (Table 3). According to Nyawira et al (2003, pp: 3), the mission of MPAs in Kenya is ‘to protect and conserve the marine and coastal biodiversity and the related eco-tones for posterity in order to enhance regeneration and ecological balance of coral reef, seagrass beds, sand beaches, to promote sustainable development, and to promote scientific research, education, recreation, and any other resource utilization’. Three main goals are also highlighted in the Kenyan context as: (1) preservation and conservation of marine biodiversity for posterity, (2) provision of ecologically sustainable use of the marine resources for cultural and economic benefits and (3) promotion of applied research for educational awareness programmes, for community participation, and for capacity building. Therefore the MPA approach has great potential of increasing biodiversity, promotion of underwater tourism, protection of the coastline besides improving livelihoods through subsistence (marine food consumption) and commercial reef fisheries. In addition, MPAs can enhance social capital for local communities adjacent to the MPA areas. The merits of MPA approach is that it helps to control human activities, protects fish breeding areas and improves ecosystem services in the protected areas. Studies by Watson el al. (1996) and McClanahan et al. (2007) have shown that MPAs are effective in restoring degraded coral reef and fish abundance on the Kenya coast.

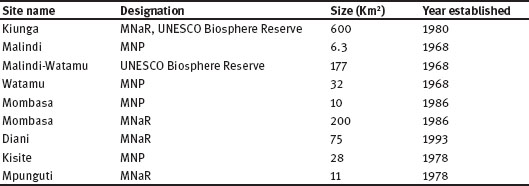

Table 3: Marine Protected Areas in Kenya ( Nyawira et al, 2003).

MNP: Marine National Park

MNaR: Marine National Reserve

The Success of MPA widely depends on the extent of stakeholders’ consultations and engagement. However, traditionally, government led protection of marine parks and reserves is often characterised with restrictive access to resources that is mainly due to the top-down policy orientation. In practice, this approach has some challenges associated with minimal community involvement. McClanahan et al. (2005) observes that most of the MPAs were created after pressure to the government from the tourism industry. Despite the ecological and economic benefits from such MPAs (Francis et al., 2002), these areas remain disputed especially for artisanal fisher communities who feel excluded from their management. It is obvious that conflicts on resource use and some sort of resistance will continue to emerge from adjacent communities dependent on the resources contained in the protected areas (McClanahan et al., 2005; Munga et al., 2010). According to Cinner et al. (2010) the failure of MPA to recognize the multiple and complex social and economic conditions at the planning and implementation processes may be attributable to their opposition by the fisher community.

Therefore, the MPA approach somewhat undermines the principles of sustainable livelihood in different ways. First its top-down nature demands high annual budgets. For example, it requires adequate human resource and equipment to conduct monitoring control and surveillance (MCS) in MPAs for policy enforcement and compliance. Besides, the MPA system is time consuming since regular reports are required on the state of such protected area. The second demerit of the system is its tendency to increase levels of illegal activities, especially where such areas are not properly zoned and lack clear boundaries. Restriction of access to a resource often bears a negative connotation as it deprives the dependants of their perceived rights and intrinsic livelihood asset thus trigger situations of vulnerability, locally considered as marginalization.

Sustainability indicators for consideration in MPAs should include among other aspects; the extent of biodiversity richness; levels of awareness and illegal activities in the area; income generation from tourism activities and extent of the ecosystem services and accruing benefits to the adjacent communities.

6.3.2 Establishment of Community Conserved Areas (CCA)

Over the last two decades, serious threats have been posed to the reef biodiversity and livelihoods of coastal people. These are mainly due to over fishing and use of unsustainable methods. Increasing coastal human population and limited economic opportunities have exacerbated the situation. In response to the challenges facing the top-down government-led MPAs with regard to policy enforcement and compliance, a hybrid management approach has evolved in the form of community based marine protected areas. This approach is participatory in design and bestows the controls to community leadership while the responsible state agency provides oversight roles.

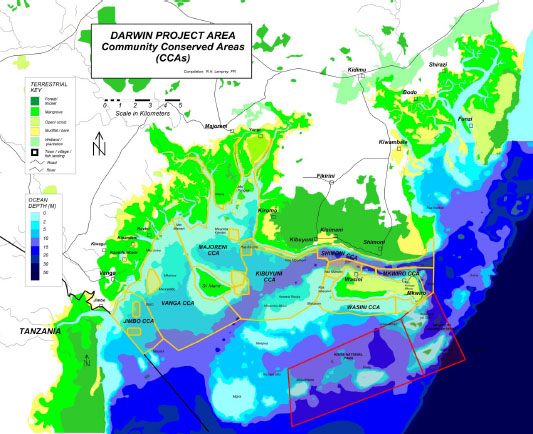

Community established MPAs, also referred as community conserved areas (CCAs), are somehow new in Kenya, having evolved over the last one decade (Maina et al., 2011). This concept is similar to the Locally Marine Managed Areas (LMMAs) which has its origin from the Pacific in Fiji where it has existed since the 1990s (Govan et al., 2008). For the CCAs to be effective, the most important requirement is the consistency in target community engagement for optimum sharing of information and learning. In Kenya, the roles of communities in the conservation objectives are supposed to be clarified and where appropriate enshrined in national policies or legislative framework. Examples of these include the Beach Management Regulation of 2007 for fisheries management; the Wildlife Conservation and Management Act of 2009 and the Forestry Act of 2005 for mangrove areas protection. The merits of this system include sharing of the operational cost, high level of community learning, guaranteed access to the resources, and social systems development. Tens of community conserved areas (CCA) have been identified and the process supported for community participation along the coast region. An established reference case is the CCA between Shimoni and Vanga of Kenya’s south coast which involves about 7 community groups made up of the artisanal fishers and fish traders. It is estimated that 12,400 hectares of the marine area is under community management as illustrated in Fig. 6 (Lamprey and Mushage, 2011; Brett, 2011).

Figure 6: South Coast Kenya Project Area Bathymetry and Community Conserved Area (Source: Flora and Fauna International – FFI).

Although the CCA approach to conservation of coastal and marine fisheries is still new along the Kenya coastal region, positive impacts have been made by some community based organizations such as Kuruwitu Conservation Welfare Association (KCWA) in the north coast, where the first community conserved marine area in Kenya was initiated in 2005 by a fisher community concerned about the declining fish catches and coral cover in their inshore fishing grounds (Pers Obs). The Community, supported by the East African Wildlife Society (EAWS), established a small area of “no fishing zone” of about 2 Km2 around the fish landing site. Interestingly, this was regularly guarded and monitored by the community members themselves. The aim of the support was to help improve the governance system by devolving the control and powers to the local communities for them to own all regulatory processes, thus enhancing their commitment to the sustainable use of the fisheries.

Figure 7: Distribution of Community Conserved Areas locally known as ‘Tengefu’ and their status of establishment along the Kenya coast (Source: Wildlife Conservation Society - WCS).

The approach also provided opportunities for forming socially cohesive leadership structures which permit learning and practicing together. Research has shown that this initiative of community designated small “no fishing zones”, locally known as tengefu in Swahili language (meaning spared or set aside), has positive impact in sustaining both marine conservation and livelihood strategies. Particularly, tengefus are critical in making fisheries management institutions more flexible and adoptive (McClanahan and Cinner, 2012). Fig. 7 shows the current distribution of tengefu initiatives along the Kenya coast and their status.

The process of establishing the tengefu involves three key steps. First, is the series of consultative meetings between members of a fisher community, conservation groups (usually non-governmental organizations) and the State Department of Fisheries (SDF). The need and objectives of conserving the identified site are discussed and agreed upon by these stakeholders. This is followed by feedback to the larger group of stakeholders including the wider fisher community, boat operators, fish traders and local residential hoteliers. This step is especially critical for all the stakeholders to understand the conservation objectives desired and attain consensus. Finally, the process results in the formation of a community management plan with mechanisms of its participatory monitoring and evaluation for successes. Therefore it can be inferred here that some of the key sustainability indicators of CCAs are the establishment of strong institutional framework for resource management, increased property rights, enhanced law enforcement and improved social capital for coastal resources dependent communities.

6.3.3 Establishment of Co-management through Beach Management Units

The top down management of fisheries resource in Kenya has evolved over the last decade to become a shared responsibility of the Government and Fishers communities. In 2006, the Government of Kenya legislated into law the formation of community led fisheries management systems that would see the formation of beach management units (BMUs) for sustainable fisheries (Kundu et al, 2010). BMUs work more or less like the CCAs but with their scope and mandates rather limited to fisheries. The aim of BMUs is to enhance management effectiveness of fisheries resource through a co-management approach. In the coast region, over 140 BMUs have been established and work very closely with the SDF in regulating fishing activities (Fisheries Department, 2009). The BMUs have democratically elected leadership structure and operate under a defined area. The underlying principle of the BMUs, as in the case with community conserved areas, is the wider stakeholders’ empowerment and participation in conservation and wise use of fisheries resources. BMUs membership comprises the fishers, fish traders, transporters and to some extent, small-scale fish processors. Therefore they provide a common platform for fisheries resource users to establish their own code of conduct and make revisions whenever necessary. This includes the possibility for their management to impose charges on non-members for accessing fisheries resource within the BMU’s areas of jurisdiction. Furthermore, the BMU leadership may also ratify recommendations from their meeting requiring members to reduce their fishing efforts, submit regular data for accuracy of fisheries statistics among other regulatory decisions that may be made from time to time. In addition, BMUs are encouraged to develop their own project ideas and mobilize resources for management of their areas of operation. Prior to their establishment, BMUs were provided with a series of training by the SDF with the objective of building their capacity in aspects of conservation, financial management, democratic leadership and governance of common property.

Although BMUs are still at their infancy stage in the coast region, they have the potential of strengthening management of coastal fisheries and marine resources. The fact they have legal status and their own by-laws stipulates their mandates and terms of operation. They are well suited to promote linkages and networks with other agencies including government departments, Community Based Organizations (CBOs) and civil societies for concerted conservation efforts. In addition BMUs have been successful in establishing cooperative and savings societies for collective selling of fish, negotiating better market prices and facilitating personal savings. Examples of this are the BMUs in Faza, Kizingitini and Kiunga in north coast, Lamu (Pers Obs). However, the BMUs will have to struggle harder to establish themselves as sustainable co-management institutions. The main sustainability challenges facing them include lack of adequate resources and technical skills for their effective management.

6.3.4 Livelihood Diversification

Livelihood diversification is today an important subject of discussion as a strategy for building resilience in rural households in Africa (Scoones, 1998; Ellis, 1999; Woodhouse, 2002). There are important lessons that can be learnt from livelihood diversification strategies: These can lead to increased household income as well as equitable distribution of income among household members. According to Ellis (1998) and Woodhouse (2002) diversification can be either at household level where the household has more than one income earner (earner diversification) or at individual level where the head of the household has income from more than one activity (i.e. activity diversification). In this regard the role of women, especially in household diversification is critical.

In Kenya, the fisheries sector is dominated by artisanal fishing methods and cultural set ups that have marginalized the dependent communities for a long time. The sector is characterized by uncertainties, low literacy levels and unawareness of sustainable livelihood options. Furthermore, as in the case for many parts of the world (Horemans and Jallow, 1997; Williams et al., 2002), the role of women in fisheries had been ignored for a long time, although the trend has changed in recent years.

Significant efforts have been put by both state and non-state agencies to increase awareness amongst the coastal communities with regard to existing opportunities for their livelihood diversification and sustainable use of coastal and marine resources. In this case, the key focus is building new capacities and strengthening existing ones so that local coastal communities can engage in other forms of income generation from the coastal and marine resources. For instance, coastal communities have been sensitized, trained and encouraged to venture into mariculture and aquaculture practices as new ways of increasing fisheries production and household income. These strategies involve the farming of aquatic organisms either in marine blackish waters (mariculture) or fresh water (aquaculture). These new livelihood strategies are being supported by the SDF in partnership with KMFRI, through various projects such the Kenya Coastal Development Project (KCDP). Silvoculture, which involves raising and replanting mangrove seedlings has proved effective in rehabilitating degraded coastal mangrove ecosystems which have been degraded by impacts from human activities. The rehabilitation of degraded mangrove ecosystems helps to improve the biodiversity and enhance breeding grounds for marine fish species.

McClanahan and Cinner (2012) observed that capacity building is a critical part of operationalizing adaptive management such as the CCA and BMUs co-management. They argue that developing skills and access to capital flow allows the marginalized communities to diversify their livelihoods. In the practical sense, capacity building provides opportunities for the fisher communities to assess and compare their investment options and enhance their adaptive capacities to respond to external factors such as seasonality especially during hard times.

There are many other aspects of capacity building strategies for the fisher community in coastal Kenya. Apiculture and silvofisheries are advocated for their potential to provide options of diversifying food production. These reduce risk in case of climate change impacts apart from providing some income opportunities for the local communities and reducing pressure in the fishery sector. Silvoculture is the practice of mangroves conservation for improved fisheries production. Apiculture, which involves beekeeping in forests such as mangroves ecosystems, has particularly been successful in areas such as Majoreni and Kibuyuni in south coast Kenya where communities are able to link their livelihood benefits with the conservation objectives. Training in value addition for optimization of income from the fishery and apiculture is critical. Examples of these are the training on solar dried and smoked fish provided by KMFRI, and honey packaging techniques by Kwetu Training Centre, a CBO working with local communities in the coast region. Other areas of capacity building include the issues of access to credit for capital asset development; awareness creation on HIV and AIDs and Other socio-sanitation related diseases which may increase vulnerability and threaten livelihoods of the fisher community.

To a large extent, capacity building is supported by both state agencies and non-state institutions that have developed programs or projects targeting artisanal fishers and rural communities. A typical example of a state initiated capacity building is the KCDP grants and scholarships for coastal communities to enhance natural resource management and community services in coast region. Some non-state agencies actively involved in capacity building along the coast region include: The East African Wildlife Society (EAWS); World Wide Fund (WWF); Coastal Oceans Research and Development in Indian Ocean (CORDIO); among many other organizations.

It can be argued that capacity building programmes in themselves may not always guarantee livelihood sustainability unless they are able to engage the local resource users and communities to effectively deal will changes in their livelihood options. IMM (2008) observes that while livelihood enhancement and diversifications are appreciated by both conservationists and development practitioners as mechanisms to promote livelihood development and discourage harmful exploitation or degradation of natural resources, the majority of efforts to this support are so far supply-driven and focused on single “blueprint” solutions. “Such solutions are not built on an understanding of the underlying factors helping or inhibiting livelihood diversification, and often fail to appreciate the obstacles faced by the poor in trying to enhance and diversify their livelihoods.”(IMM, 2008, pp:6).

Thus, livelihood diversification ought to take into consideration realistic options of reducing over-dependence on resources within conserved areas, while compensating the dependent communities whose access to the resources is restricted. Here we suggest that the list of sustainability indicators for livelihood diversification may not be exhaustively presented, but it includes: the capacity and capability of community groups to develop opportunities for positive livelihood change through initiation of new livelihood strategies; diversity of income sources and enhanced marketing strategies for community or household members; institutionalization of community governance structures for policies, legal framework and participatory resource monitoring.

6.4 Sustainability Indicators

Economic growth in coastal Kenya has eroded cultural ways of fishing, leading to overexploitation of many reef fishes. These practices together with the increasing pressure from coastal human population will increasingly degrade the less resilient marine ecosystems. In turn, this will have serious ramifications for the livelihoods of the coastal communities. Therefore, it is important to understand the tools and/or methods of measuring and reporting progress towards sustainability of the coastal fisheries and livelihoods. In essence, indicators or indices of sustainability should be determined upfront and periodically evaluated to confirm the progress achieved. Indicators can either be quantitative or qualitative depending on the purpose, but the quantitative ones are often more convincing and widely preferred (Gallopin, 1997).

Table 4: Sustainability Indicators (SI) of fisheries and livelihood in coastal Kenya.

| SI Category | Aspect checked | Examples of SI measured |

| Ecological | Ecosystem health | Mangrove, seagrass and coral cover Biodiversity richness Fish abundance Pollution levels |

| Biological | Productivity and reproduction | Primary production Population growth rate Population mortality rates |

| Socio-cultural | Social and cultural security | Human demography Food security Public health and safety Equity Capacity (Education and training) Awareness levels Voluntary participation Gender roles Vulnerability and resilience Conflicts Crimes rates |

| Economic | Macroeconomics and Microeconomics | Gross Domestic Production Per capita income Household in come Employment Transport Market opportunities Savings and credits |

| Institutional and Organizational | Policies and Governance framework | Mandates Interests Values, Norms and Beliefs Groups or Associations Collaborations and partnerships Area of operation Behavioural changes |

| Political | National and local political dynamics | Leadership regimes Democratic decisions Level of consensus |

In Kenya, despite the wide discussions with regard to the sustainability of coastal fisheries and livelihoods, the level of actual operationalization of the sustainability indicators to inform management decisions is still quite low. This may explain the reasons why success in coastal and marine areas conservation is rather limited in either context or geographical areas. Where intervention mechanisms have been enforced, the indicators of success tend to be pegged on observation of easy targets such as, changes in fish catch, species diversity, size and number of conserved areas. However, as noted in the previous sections, sustainability indicators should transcend beyond merely observing single factors in isolation, such as environmental, social, economic or political conditions. Rather, to the largest extent possible, the indicator should encompass the dimensions of ecological, biological, social, economic, institutional and political conditions surrounding a fishery in question. Indeed these six dimensions tend to influence the trajectory sustainable development the fact which has been reverberated by Hediger (1997).

By aggregating sets of indicators identified from the above six dimensions, measurable indices relevant to the context in discourse can be built and monitored for effectiveness in sustainable management of the coastal fisheries. In table 4, an attempt is made to elaborate the six sustainability indicators (SI) which are commonly used to monitor the performance of coastal fisheries and local livelihoods in Kenya. However, the extent to which the data and information on these indicators are adequate and relevant to the sustainable fisheries and livelihoods management is a subject of debate among the key agencies and stakeholders in the fisheries sector of Kenya.

It should be considered that sustainability of coastal fisheries and the local livelihood cannot be discussed in isolation of the entire ecosystem. According to Carney (1998) five critical assets should be taken into consideration with regard to livelihood sustainability. These are the human capital; natural capital; financial capital; social capital; and physical capital. Since fisheries resources, environment and society are tightly interrelated pillars, holistic assessment of their sustainability indicators should be practised to pinpoint success and weaknesses of any management strategy put in place. For instance, assessment of fisheries and livelihood sustainability in protected areas should interrogate: 1) Why specific management approaches are preferred for implementation; 2) Who was or is being affected or benefitting from the implemented approach and 3) How the approach affects the resource and people in general including political aspects. This set of questions assist to establish measurable targets that can be monitored and evaluated to ascertain whether fisheries conservation objectives and local livelihood needs are being sustained. Reasoning in the line of capital theory approach to sustainable development, as introduced previously, the fisheries governance systems in Kenya should be re-evaluated on the basis of their alignment to either weak or strong sustainability.

6.5 Experience And Lessons Learned

Some significant progress has been made towards enhancing sustainable coastal fisheries and livelihoods in Kenya. A critical part of the approaches being implemented is the participatory process. Experience has shown that the involvement of local communities in planning and implementing specific resource management strategies is a better option that not only inculcates process ownership but also provides opportunities for flexible governance. Such participatory approaches enable the relevant authorities to make an entry point into the community and in a manner that facilitates social leaning and establishment of own rules. In coastal fisheries management the BMU, CCA and capacity building approaches have positive influence on the five components of sustainability.

However, levels of success and impacts of whatever participatory approach designed cannot be assumed. It is necessary to measure and monitor the process using reliable sustainability indicators. The indicators should be integrative and help to provide answers to the why, who and how questions discussed earlier. Answers to the questions should also be bundled and linked to the three pillars of sustainable development (environmental, economic, social and governance). In this perspective, it is worthwhile to note that the above sustainability indicators may switch to either positive or negative sides due to external drivers such as climate change, increased due to coastal population growth, among other drivers. Further studies are recommended in this line of thought so as to ascertain whether the current coastal fisheries management and livelihood strategies are indeed sustainable in the long term.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to appreciate the support from Mr. Nassir Amiyo of EAWS and Dr. Muthiga Nyawira of WCS who provided CCA maps used in this article. We are also indebted to staff of KMFRI for providing some of the data and information used in this chapter. Specifically, special thanks to Mr. Noah Ng’isiange who provided the fisheries map, Mr. Elijah Mokaya who provided access to most of the literature material and Mr. Stephen Mwakiti whose photograph has been used in this article.

References

Allison E.H. & Ellis F. (2001). The livelihoods approach and management of small-scale fisheries. Marine Policy, 25, 377–388.

Allison E. H. & Horemans B. (2006). Putting the principles of the Sustainable Livelihoods Approach into fisheries development policy and practice. Marine Policy, 30 (6), 757-766.

Anam, R. & Mostarda, E. (2012). Field identification guide to the living marine resources of Kenya. FAO species identification guide for fishery purposes. Rome, 357p.

Blignaut, J.N. & De Wit, M.P. (1999). Integrating the natural environment and macroeconomic policy: Recommendations for South Africa. Agrekon, 38 (3), 374-395

Brett, R. (2011). Cost benefit analysis. Fauna & Flora, 14, 22-25.

Carney, D. (1998). Sustainable rural livelihoods: what contribution can we make? London: DFID.

Carney, D., Drinkwater, M., & Rusinow, T., et al. (1999). Livelihood approaches compared: a brief comparison of the livelihoods approaches of the UK Department for International Development (DFID), CARE, Oxfam and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). A report to DFID.

Chambers, R. (1989). Editorial introduction: vulnerability, coping and policy. IDS Bulletin, 20 (2), 1–7.

Chambers, R. & Conway, R. G. (1991). Sustainable rural livelihood: practical concepts for the 21st Century. IDS Discussion Paper, 296, University of Sussex, Brighton.

Christie P., Fluharty, D.L., & White, T.A. et al. (2007). Assessing the feasibility of ecosystem-based fisheries management in tropical contexts. Marine Policy 31:239-250

Cinner, J. E., McClanahan, T. R. & A. Wamukota (2010). Differences in livelihoods, socioeconomic characteristics, and knowledge about the sea between fishers and non-fishers living near and far from marine parks on the Kenyan coast. Marine Policy, 34(1), 22-28.

Costanza, R. (Ed) (1991). Ecological Economics: The science and management of sustainability. New York: Columbia University Press.

Daly, H.E. (1996). Beyond growth. The economics of sustainable development. Boston: Beacon Press.

Davies S. (1996). Adaptable livelihoods coping with food insecurity in the Malian Sahel. London: Macmillan Press.

De Wit, M.P. & Blignaut, J.N. (2000). Review: a critical evaluation of the capital theory approach to sustainable development. Agrekon, 39 (1), 111-125.

Ellis, F. (1998). Household strategies and rural livelihood diversification. Journal of Development Studies, 35 (1), 1-38.

Ellis, F. (1999). Rural livelihood diversity in developing countries: Evidence and policy implications. Natural Resource Perspectives, 40. London: Overseas Development Institute.

Ellis, F. (2000). Rural livelihoods and diversity in developing countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

FAO (1989). Sustainable development and natural resources management. Twenty-Fifth Conference, Paper C 89 (2) - Sup. 2. Food and Agriculture Organization, Rome.

FAO (1995). Guidelines for responsible management of fisheries. In Report of the Expert Consultation on Guidelines for Responsible Fisheries Management, Wellington, New Zealand. FAO Fisheries Report, 519.

FAO (2012). The state of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2012. Rome, 209 p.

Fletcher, W.J., Chessonio, J., & Fisher, M. et al. (2002). The “How To” guide for wild capture fisheries. National ESD reporting framework for Australian fisheries: FRDC Project 2000, 145, 119–120.

Fondo N.E. (2004). Assessment of the Kenyan marine fisheries from selected fishing areas. Final Report, UNU Fisheries Training Programme, Reykjavik, Iceland.

Francis, J., A. Nilsson, & D. Waruinge (2002). Marine protected areas in the Eastern African region: how successful are they? Ambio, 3, 503–11.

Fulanda, B. (2003). Shrimp trawling in Ungwana Bay: A threat to fishery resources. In J. Hoorweg & N. Muthiga. (Ed.). Recent advances in coastal ecology: Studies from Kenya, 233-242. Leiden: African Studies Centre.

Gallopin, G C (1997). Indicators and their Use: Information for Decision-making. In Moldan, B., Billhartz, S., & Matravers, R. (eds.). Sustainability Indicators: A Report on the Project on Indicators of Sustainable Development, John Wiley and Sons, Chichester, 13-27.

Garcia, S., Sparre, P. & Csirke, J. (1989). Estimating surplus production and maximum sustainable yield from biomass data when catch and effort time series are not available. Fish. Res., 8: 13-23.

Gell, F.R., & Roberts, C.M. (2003). Benefits beyond boundaries: the fishery effects of marine reserves. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 18, 448–455.

Glaesel, H. (1997). Fishers, parks, and power: The socio-environmental dimensions of marine resource decline and protection on the Kenya Coast. (Ph.D. Thesis). Madison: University of Wisconsin.

Govan H., Aalbersberg W., & Tawake A., et al. (2008). Locally managed marine areas: A guide for practitioners. The Locally Managed Marine Area Network, 3, 64p.

Government of Kenya, (2012). Marine Waters Fisheries Frame Survey 2012 Report. Department of Fisheries, Ministry of Fisheries Development, 85 p.

Gulland, J.A. (1971). The Fish Resources of the Ocean. Fishing News (Books), West Byfleet, 255 p.

Hediger, W. (1997). Towards an ecological economics of sustainable development. Sustainable development, 5, 101-109.

Horemans, B. & A. Jallow (1997). Current state and perspectives of marine fisheries resources co-management in West Africa. In A.K. Norman, J.R. Nielsen & S. Sverdrup-Jensen. (eds). Fisheries co-management in Africa: Proceedings from a regional workshop on fisheries co-management, 12, 233-254. Fisheries Co- management Research Project, Hirtshals: Institute for Fisheries Management and Coastal Community Development.

IFRC (2010). IFRC guidelines for livelihoods programming. Strategy 2020. Geneva, Switzerland.

IMM (2008). Sustainable Livelihood Enhancement and Diversification – SLED: A Manual for Practitioners. IUCN, International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

Kelleher G (1999). Guidelines for marine protected areas. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK, 24, 107p.

Knutsson, P (2006). The Sustainable Livelihoods Approach: A Framework for Knowledge Integration Assessment. Human Ecology Review, 13(1), 90-99.

Kundu, R., Aura C.M., & Muchiri, M., et al. (2010). Difficulties of fishing at Lake Naivasha, Kenya: is Community participation in management the solution? Lakes and Reservoirs Research and Management, 15, 15-23.

Lamprey, R., & Murage, D.L. (2011). Saving our seas: Coast communities and Darwin collaborate for a new future. Swara, 41-48.

Larkin P.A. (1977). ‘’An epitaph for the concept of maximum sustainable yield’’ Transactions of the American Fisheries Society, 106, 1-11.

Levin, S.A. & Lubchenco, J. (2008). Resilience, robustness, and marine ecosystem-based management. BioScience, 58, 27-32.

Mace, P.M. (2001). A new role for MSY in single-species and ecosystem approaches to fisheries stock assessment and management. Fish Fish, 2, 2–32.

Maina, G. W., Osuka, K., & Samoilys, M. (2011). Opportunities and challenges of community-based protected areas in Kenya. CORDIO, East Afica.

McClanahan, T. R. & Kaunda-Arara, B. (1996). Fishery recovery in a coral-reef marine park and its effect on the adjacent fishery. Conservation Biology, 10 (4), 1187- 1199.

McClanahan, T.R., Maina J., & Davies J. (2005). Perceptions of resource users and managers towards fisheries management options in Kenyan coral reefs. Fish Manag Ecol, 12, 105-112.

McClanahan T. R., Graham N. A. J., & Calnan J., et al. (2007). Toward pristine biomass: reef fish recovery in coral reef marine protected areas in Kenya. Ecological Applications, 17(4), 1055– 1067.

McClanahan, T.R. & Cinner E. J. (2012). Adopting to a changing environment: Confronting the consequences of climate change. Oxford University Press. Inc. New York.

Metcalf, S.J., Gaughan, D.J. & Shaw, J. (2009). Conceptual models for Ecosystem Based Fisheries Management (EBFM) in Western Australia. Fisheries Research Report, 194. Department of Fisheries, Western Australia. 42p.

Mohammed, M.O. (2002). Fish catch composition and some aspects of reproductive biology of Siganus sutor along the Malindi-Kilifi marine inshore waters. (M.Phil thesis). Eldoret: Moi University, Department of Fisheries.

Munga C. N., Mohamed, O.S.M., & Obura, O.D., et al. (2010). Resource Users’ Perceptions on Continued Existence of the Mombasa Marine Park and Reserve, Kenya. West Indian Ocean J. Mar Sci., 9(2), 213-225.

Munga, C.N., Kimani, E., & Vanreuse, A. (2013). Ecological and socio-economic assessment of Kenyan coastal fisheries: the case of Malindi-Ungwana Bay artisanal fisheries versus semi-industrial bottom trawling. Afrika Focus, 26 (2), 151-164.

Nyawira, M., Maina, J., & McClanahan, T. (2003). The Effectiveness of Management of Marine Protected Areas in Kenya. A report prepared for the international tropical marine environment management symposium, ITEMS 2, Manila, Philippines.

Oxford dictionary of English. (2010). Oxford University Press.

Pauly, D., Christensen, V., & Guénette, S., et al. (2002). Towards sustainability in world fisheries. Nature, 418, 689-695.

Pezzey, J.C.V. (1989). Economic analysis of sustainable growth and sustainable development. Enveironment Department working paper, 15. The Word Bank, Washington D.C.

Rosenberg, A.A. (2003) Managing to the margins: the overexploitation of fisheries. Front Ecol. Environ., 1(2), 102-106.

Schaefer, M. (1954). Some aspects of the dynamics of population important to the management of the commercial marine fisheries. Bull.I-ATTC/Bio.CIAT, 2, 247-68.

Scoones, I. (1998). Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: A framework for analysis. Institute of Development Studies Working Paper, 72. University of Sussex: Brighton.

Scoones, I. (2009). Livelihoods perspectives and rural development. JPS, 36 (1), 26 p

Slocombe, D.S. (1993). Implementing ecosystem-based management. BioScience, 43 (9), 612 - 622.

Slocombe, D.S. (1998). Lessons from experience with ecosystem based management. Landscape and Urban Planning, 40, 31-39

Sparre, P. & Venema, S.C. (1992). Introduction to tropical fish stock assessment. Part I. Manual. FAO Fisheries Technical Paper, 306 (1 Rev, 1), 376p. Rome.

Stern, D.I. (1997). Capital theory approach to sustainability: A critical appraisal. Journal of Economic Issues. XXXI (1), 145-173.

Toman, M.A. (1994). Economics and “sustainability”: Balancing trade-offs and imperatives. Land Economics, 70(4), 399-413.

Troadec, J.-P. (1977). Méthodes semi-quantitatives d’évaluation. FAO Circ. pêches, 70, 131-141.

Walters C. and Maguire J. (1996). “Lessons for stock assessment from the northern cod collapse”. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries, 6, 125–137.

Wakwabi, E., Abila, R. O., & Mbithi, M.L. (2003). Kenya Fish Sub-sector: Fish Sector Development strategy for Kenya. Consultancy Report for the International Trade Centre, United Nations Conference on Trade And Development, World Trade Organization Joint Integrated Technical Assistance Program to Least Developed and Other African Countries. Kenya Department of Fisheries, Association of Fish Processors and Exporters of Kenya. Nairobi.

Watson M., Righton D. A., & Austin T.J., et al. (1996). The effect of fishinh on coral reef fish abundance and diversity. J. Mar. Bio. Assoc. 76, 229 -233.

WCED (1987). Our Common Future: The Bruntland Report, Oxford University Press from the World Commission on Environment and Development, New York, 247p.

Williams, M.J., Chao, N.H., & Choo, P.S., et al. Wong, Eds. (2002). In Global symposium on women in fisheries: Sixth Asian fisheries forum. Penang: World Fish Center. (www.worldfishcenter.org > scientific publications > 2003-2000).

Woodhouse, P. (2002). Natural resource management and chronic poverty in Sub- Saharan Africa: An overview paper. CPRC Working Paper, 14. Manchester: University of Manchester, Institute for Development, Policy and Management.