Stage 6

Handover and Close Out

Chapter overview

Stage 6 of a building project is a period of intense activity where the design team and the contractor are already thinking of the next project and the client is keen to start occupying their new building. It is at this stage that vital steps can be rushed or overlooked entirely, the impact of which can result in years of underperformance.

This stage covers the process of ensuring that what has been built and handed over to the client will deliver the Sustainability Aspirations over the long term. Evidence that the Sustainability Strategy has been followed should be provided and shared with all members of the project team.

Where the key performance indicators (KPIs) within the Sustainability Aspirations require to be demonstrated at this stage (for example, airtightness), tests should be carried out. Where the Sustainability Aspirations relate to the project in use, then the groundwork for testing in Stage 7 can be laid.

Key coverage in this chapter is as follows:

Introduction

By Stage 6 the building works are completed, building services go through initial commissioning and testing and are run for the first time, and responsibility for the building passes from those who designed and constructed it to those who will manage its operation. Some elements of the project will be wrapped up entirely at this stage, such as the site waste management plan (SWMP); others will require active management to deliver, such as meeting energy performance targets over the long term.

The client will require the necessary information (and possibly training or instruction) to take forward the process of optimising the building’s performance during Stage 7. As the contract administration is concluded, it is important that all of the contractual obligations have been met.

The Sustainability Checkpoints at the end of this stage require that:

In addition, the project team should begin to review initial monitoring data in order to help optimise the building’s performance and inform future projects.

What are the Core Objectives of this stage?

The Core Objectives of the RIBA Plan of Work 2013 at Stage 6 are:

Stage 6 is the point in the project where theory and practice meet. The Core Objective is to ensure that the client is able to occupy and start operating the building as expected. Any snags must be rectified as quickly as possible so that the process of optimising the building can commence.

Why is commissioning and testing so important?

Many building services, such as fire alarm systems and lifts, require to be commissioned and tested and evidence that they function properly must be provided at handover. To ensure that the sustainability performance of a building is optimised, this process needs to go further to confirm that services are not simply functioning but that the set points of control systems are in line with a controls strategy (see below) and that the building fabric meets the project specification.

Thermal image survey

A thermal image shows the surface temperature of objects in view. Ideally used on a cold day, with the building heated, hot spots show where insulation might be missing or if there is a significant cold bridge. From inside, the reverse is true.

Airtightness testing

The introduction of airtightness testing in support of energy calculations for new buildings has done much to concentrate the minds of design and construction teams on ensuring that buildings are both properly detailed and that care is taken during construction, as discussed in previous stages.

Tests should be carried out in accordance with the requirements of the Air Tightness Testing and Measurement Association (www.attma.org) by qualified specialists.

The contracting team will have been aware of these requirements throughout Stage 5 and with whom the responsibility to deliver lies. For complex buildings, preparing a specific package of information which addresses airtightness during construction is a valuable exercise.

Regardless of the scale of the project, it is essential that testing is proportionate to the impact on performance and that commissioning (like the design of systems) is undertaken in light of the client’s needs and future ability to manage and maintain the building fabric and systems.

At Stage 1, Sustainability Aspirations will have been identified, along with a Sustainability Strategy designed to deliver them and the mechanisms by which the delivery of these are to be evidenced or tested, for example through the use of thermal imaging and airtightness testing.

What ‘As-constructed’ Information is required at Handover and Close Out?

The handover of a project normally entails the assembly of ‘as-constructed’ drawings, operating and maintenance (O&M) manuals, including test and commissioning certificates, the provenance of materials, and health and safety information. This information can fulfil one or more of a number of roles. Those that are relevant to sustainability are listed below:

- confirming that certain items have been tested and have been shown to be working and properly calibrated, such as temperature sensors, to ensure the building can be accurately controlled

- completing the health and safety project file by documenting how the building can be safely maintained, as planned maintenance will lengthen the life of building fabric and services

- providing information on the care and cleaning of building fabric, fixtures and fittings – materials and finishes should be chosen to minimise the need for toxic cleaning products

- providing details of planned maintenance requirements, such as the replacement of filters in air handling units to ensure that equipment is running efficiently

- providing details of cyclical maintenance, such as the repainting of windows, as regular maintenance is more cost effective than reactive maintenance when a problem occurs

- confirming that the materials meet key elements of the project specification, such as the provision of Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certificates covering timber supplies to demonstrate that Sustainability Targets have been met

- providing performance test certificates, such as an airtightness test certificate in line with ATTMA testing procedures, necessary to demonstrate that Sustainability Targets have been met

- providing operating instructions for specific items of equipment to ensure that the building management team is able to optimise the building.

It is also essential to check that those Sustainability Aspirations which relate to procurement, good management and material selection/detailing have been met. For example, where timber supplies are required to be certified by the FSC or the Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC), are certificates available that show both the chain of custody and matching quantities?

All of this information can mount up to a significant pile and there is a danger that it can overwhelm the building management team, who may only need specific pieces of information for the day-to-day operation of the building.

O&M manuals

An O&M manual must be both fit for purpose and proportionate to the building to which it relates. Standard templates are available which comply with industry guidance.

In simple terms, the O&M manual provides the information needed for the building to be properly operated and maintained, including the replacement of fabric and systems and eventual decommissioning and demolition of the building.

Its contents should detail the construction of the building and the equipment it contains. An O&M manual is not a static document. As the building is used, the O&M manual should be updated to record planned maintenance, refurbishment and replacement as they take place. In other words, there is little point in knowing the replacement interval for, say, filters if the date on which they were last replaced has not been recorded.

Keep the building manager informed

The Sustainability Strategy for the building and the detailed services strategy must be developed with an understanding of the user’s needs, how robust a solution has to be and how proactive or otherwise the user may be. Even the best O&M manual is unlikely to describe this and yet it is vitally important that this information is communicated to those with responsibility for managing the building (see the example of the hybrid ventilation strategy developed in Stage 4, page 150).

They therefore must have access to both the design team and the contractor’s team in order to interrogate the original design assumptions and ensure that the building, as initially set up, accommodates the actual pattern of use of the building, as far as it can be ascertained. Failure to do this will become all too apparent at Stage 7.

Completion of energy and sustainability assessments

The Sustainability Aspirations are minimum performance levels and require mechanisms by which they will be tested. For some projects they may have included a reliance on achieving a minimum Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) rating, or minimum score using a preexisting assessment scheme, such as a BREEAM assessment. It is at this stage that an EPC and/or a Post-Construction Stage (PCS) BREEAM assessment must be provided.

Assessments methodologies

Both the calculations which produce EPCs and off-the-shelf assessment methodologies are asset based and reflect an assumed standardised occupation pattern in order to allow a direct comparison between projects (the benefits and limitations of such assessments are discussed elsewhere in this guide). It is essential that they are not relied upon as the only proof of sustainability performance.

Where the Sustainability Aspirations include KPIs, such as minimising embodied energy and toxicity, or waste production etc, then the Sustainability Champion identified at Stage 1 is responsible for assessing the evidence that supports the achievement of these KPIs.

Verification involves checking that those products and materials specified at Stage 4 were actually used during Stage 5, and that nothing was value engineered out which erodes the Sustainability Strategy and the delivery of the Sustainability Aspirations.

As previously described in Stage 5, it is all too easy on a busy building site for materials and even entire components to be substituted because the alternatives are readily available, cheaper or easier to use. If those placing the orders are unaware of the specific reasons for the original choice, such as lower embodied energy or a performance advantage, then such action is understandable. If discovered late in the project, reversion to the original specification can have significant cost and time implications.

The Sustainability Champion may also be required, as described in Stage 1, to undertake a detailed audit of materials and products used in order to calculate, say, the embodied energy in the building and provide this result as part of the final sustainability report.

It is also at this stage that all members of the project team should reflect on any Feedback that was available at Stage 0, including revisiting any PoEs or building user satisfaction surveys undertaken of previous buildings or the building prior to refurbishment and start to prepare for the follow-up surveys recommended in Stage 7.

What role does building management play?

Where possible and appropriate, it is beneficial to identify early in the process (ideally no later than Stage 3) who will manage the building, what their need for information might be and what skills it can be reasonably assumed they will bring to the task. While it may seem obvious to ask ‘Who will manage the building?’, it is surprising how often this can be overlooked, even by relatively sophisticated clients, until the very end of a project. Of course, not every building can justify a team of facility managers. Regardless of the scale of the project, assistance will be valuable in ensuring long-term sustainability.

This may necessitate the provision of training in the operation of specific systems, such as HVAC, CHP and biomass heating systems etc within the building, or ensuring that the building manager has access not only to the ‘As-constructed’ Information discussed above but to those specialists who can interpret their needs as they learn how the building actually performs in use.

Any project, however small, may well change the way in which an existing building performs. In the case of a conversion or a new building, that performance may have been predicted with a reasonable degree of accuracy, but building physics are determined by a complex interplay of fabric performance, services and control settings, as well as occupant behaviour.

In addition, the way a building is actually used may vary from the original expectation. For example, a new community facility may prove so popular that its opening hours and range of activities and visitor numbers are increased. This may lead to a greater energy demand. Rather than this automatically being seen as a bad thing, it might actually be an indicator of a greater success. Nonetheless, the detailed monitoring described in Stage 7 will highlight the phenomenon, allowing the building management team to understand and explain what is happening while still optimising the building’s performance over time.

In planning for the follow-up surveys and evaluations described in Stage 7, it is important to ensure that there is a clear understanding of who is responsible for organising these, what the objective is in undertaking them, who will receive the information and what action they are going to take as a result. One objective may be to demonstrate that one or more specific Sustainability Aspirations identified at Stage 1 has been achieved. Alongside this, however, the results must be critically assessed in terms of ‘What can we do better?’.

Energy assessments

It is important to ensure that what might be being metered or measured on completion is the same as what was assessed during the design process. There have been many stories in the media of supposedly ‘green’ buildings using more energy in use than predicted and indeed reflected in an EPC.

There are two national calculation methodologies (NCMs):

- the Standard Assessment Procedure (SAP) for domestic buildings, which is used for demonstrating compliance of new dwellings: www.bre.co.uk/sap2012

- the Simplified Building Energy Model (SBEM), used predominately for demonstrating compliance of non-domestic buildings (although in some circumstances building simulation models might be used): www.ncm.bre.co.uk

Both are used to produce EPCs. Neither calculation includes unregulated energy used by equipment, such as computers, TVs and washing machines etc. Both calculations also assume a standardised pattern of use in order to create a comparable asset rating.

It is at this point in the project that the building management team has to take responsibility for achieving the latent performance lying dormant in the building. If the building has been designed to work passively, then the benefits of low running and maintenance costs will only become apparent if the building is optimised and is properly managed, which in turn requires continuous monitoring as described in Stage 7.

What does optimisation of the building involve?

The process of optimising the efficiency of a building starts at the point of handover and continues into Stage 7. It never truly stops, as both the way in which buildings are used and the technologies and equipment they are required to accommodate can change over time.

As part of any commissioning and testing process, the project team should review, with the building or facilities management team, the overall Sustainability Strategy and the assumptions with regard to hours of use, temperature expectations etc, that were made at Stages 1 and 2.

Taking responsibility

Having agreed the control philosophy at Stages 1 and 2, which has been reviewed at each subsequent stage, the project team can hand the main responsibility for implementation to the building management team. In turn, the building management team must hold the project team to account if things are not working as expected.

Commissioning on small projects

With small, and especially remote, projects it can be very hard to persuade suppliers to visit site post-completion, particularly if the value of the works and the likelihood of a repeat commission seem low. It is important to be aware of this and to build in retentions or rewards that can ensure attention is committed to solving the many problems that can arise, such as:

- On completion of a new extension in a remote location, the clients were unhappy that their solar hot water system seemed to deliver little in the way of benefits and the boiler was required to heat their hot water, even in summer. Eventually, on investigation, it was discovered that the flow and return pipes between the solar panels and the hot water cylinder had been connected the wrong way round.

- On completion of a house, one of the external blinds was not working but it proved extremely difficult to incentivise the manufacturer/installer to return to the remote site.

Agreement should be reached regarding the initial set points of equipment based on the time of year and expected level of initial use. Literally, on the first day of handover, at what time of day should the boilers come on and what temperature should the heating be set to?

For any reasonably complex project it is likely that the building services are both zoned and controlled by a sophisticated control system, which incorporates a range of temperature and other sensors, such as CO2, relative humidity, light levels and movement detection (to detect occupancy) as well as external weather conditions. These provide valuable insights into how the building is operating as well as being a potential method of control.

However, operational information is only of use if someone monitors it and acts on it when necessary. At handover, a chain of command must be established with the building manager at its head. This will ensure that any initial teething problems or equipment faults are resolved quickly and that adjustments to control set points are made and the impact recorded.

Although the major gains in optimising a building can be made in the first few months after handover, the process should continue throughout Stage 7.

Optimising the energy performance of a refurbishment

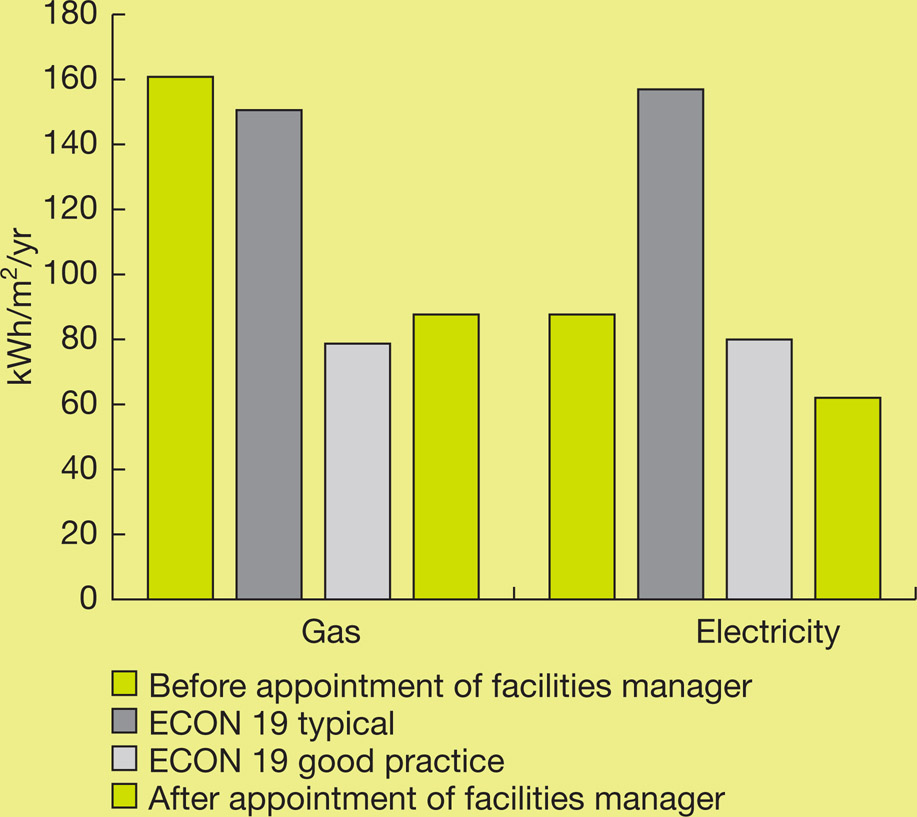

The conversion and refurbishment of a Victorian school was completed in 1999. The client’s KPI for energy use was to match what was then considered to be good practice for new build offices.

At handover, however, the energy performance of the building was closer to that of a typical new office building. Over a period of 3 months, the facilities management team reset the timing and temperature settings of the heating and ventilation systems, identified some malfunctioning valves and pumps and had the software controlling the boilers adjusted to be more responsive to the heat demand. Taken together, these actions dramatically reduced the overall energy demand of the building by 40%.

The school was revisited some 12 years after the refurbishment. The published results (Atkins and Emmanuel, 2014) showed that, in the main, the building was still performing very well. Weekly energy and water readings had been taken over the intervening years and these had highlighted any changes in performance, such as a water leak at one point, which prompted the facilities management team to respond very quickly.

Figure 6.1

Performance before and after optimisation

A building user satisfaction survey did, however, reveal that in summer some parts of the building overheated, which prompted the simple solution of opening the inner secondary glazing overnight to allow those areas to cool down more quickly.

Why is snagging important?

The presence of any defect absorbs the time of all the participants in the project and costs money so, not surprisingly, snagging can be seen by the design team and contractor as an avoidable necessity to be delayed until the end of the rectification period and by the client as a disappointing conclusion to what may otherwise have been a successful project.

If left unresolved snags can escalate to a point of major disagreement or even legal action and so it is vital that they are dealt with as soon as possible. If not addressed, the impact of poorly controlled heating and ventilation systems will be to increase CO2 emissions and energy bills while shortening maintenance intervals and, ultimately, equipment life with possible adverse impacts on indoor comfort and productivity.

Soft Landings

Soft Landings offers a process whereby the ‘blame game’ can be avoided and everyone’s mind can be concentrated on resolving issues quickly.

Details of the Soft Landings process can be found on BSRIA’s website: www.bsria.co.uk

How does sustainability impact on the Key Support Tasks at Stage 6?

The RIBA Plan of Work 2013 lists three Key Support Task at Stage 6: implementing the Handover Strategy, providing initial Feedback and updating the Project Information, primarily the ‘As-constructed’ Information on which the building managers will rely.

What are the Sustainability Checkpoints at Stage 6?

- Has assistance with the collation of post-completion information for final sustainability certification been provided?

- Have tests, such as air infiltration and thermal imaging, been completed?

- Have snagging items been rectified?

- Has a controls strategy been developed and implemented?

- Is the building management team fully informed about the design concept, sustainability targets and controls strategy?

- Has the Handover Strategy been fully implemented?

- Has a PoE survey been considered and commissioned?

What are the Information Exchanges at Stage 6 completion?

The ‘As-constructed’ Information should be reviewed and updated as necessary.

6 Chapter summary

At Stage 0, sustainability goals were established and, at Stage 1, Sustainability Aspirations were set as part of the Initial Project Brief. At Stage 2, a Sustainability Strategy was developed to deliver the Sustainability Aspirations, including any KPIs. Throughout the project, both the Sustainability Strategy and the Sustainability Aspirations have been reviewed and interim reports prepared detailing progress on their delivery.

Stage 6 is the time for the client and project team to prepare to hand over the building to the building management team and for the Sustainability Champion to prepare a sustainability report.

In addition, the ground must be prepared for completing those project sustainability assessments, such as PoE, which require the building to be in use at Stage 7.

Above all, the project Sustainability Champion has a responsibility to ensure that the rest of the project team members do not drift away as their attention is drawn to other projects.