Risk Management in Takaful

Risks are at the heart of insurance, which may be divided into general or non-life insurance and life insurance. While the first of these is concerned with risks of losses arising from various kinds of hazards, the second was originally concerned with mortality risk but offers a variety of savings and investment products in connection with life insurance, including pensions. The economics of insurance depend crucially on the “law of large numbers” in underwriting risk, according to which, in the absence of high correlation, the larger the set of risks insured in an underwriting pool, the greater the degree of risk diversification in the pool, and hence, the smaller the (underwriting) risk of a large proportion of the insured losses occurring in a given time period, and hence, of claims on the pool exceeding premium payments from policyholders for the period.

Risk management in all insurance undertakings is concerned with underwriting risk, but life insurance, and to a lesser extent, non-life insurance are also concerned with risks similar to those faced by banks, namely: (a) investment risks arising from the investment of funds received from policyholders, the nature of which (market and credit risk) depends on the type of assets in which the funds are invested; (b) liquidity risk (inability to meet obligations because assets cannot be converted into cash quickly enough); and (c) operational risk—that is, the risk of failures or breakdowns in internal systems and procedures, whether from human error or from deficiencies in the systems themselves. While the risks that concern takaful undertakings include the above, there are also some special considerations that are discussed below.

The management of these risks is an important part of the operation of insurance undertakings and has gained attention in the industry because of a number of important factors. For example:

- Shareholders and investors want to know that insurers' strategic decision making is based on a reliable assessment of both risks and capital needs.

- Financiers within the capital markets expect that insurers, in their efforts to use scarce resources efficiently, will determine their capital requirements according to a comprehensive assessment of their risks.

- Rating agencies are increasingly basing their evaluations of insurers on the manner in which they identify, aggregate, and manage risk.

- Regulators worldwide are increasingly evaluating insurers with risk-based approaches.

To recap what has been mentioned in previous chapters, in a takaful undertaking, the participants (policyholders) make a premium contribution on the Shari'ah juristic basis of tabarru' (donation) to a common underwriting fund, which will be used mutually to indemnify them in case they suffer specified types of losses. In family takaful (which includes Shari'ah-compliant life insurance), the premium contribution includes a savings or investment element, which is not a donation into a mutual risk pool, but rather a payment into a participant's investment account. The underwriting in a takaful is thus undertaken on a mutual basis, similar in some respects to conventional mutual insurance. A typical takaful undertaking consists of a two-tier structure that is a hybrid of a mutual and a commercial form of company—the latter being the takaful operator—although in theory, it could be a pure mutual structure. Hence, the risks in a takaful undertaking fall partly on the policyholders' funds, which include the takaful (underwriting) funds and the policyholders' investment funds, and partly on the TO. The risks to which the takaful and policyholders' investment funds are exposed are the market, credit, and liquidity risks attaching to the assets of these funds.

In addition to the risks mentioned above, takaful undertakings are exposed to risks that result from their structure and their need to be Shari'ah compliant. These risks fall on the TO rather than on the underwriting pools. A TO is, thus, exposed to the following types of risk:

1. Operational risk, which, owing to the need for compliance with Shari'ah rules and principles, involves reputational risk as a result of a failure in its systems and procedures for ensuring Shari'ah compliance. Such compliance relates to the investments of underwriting and investment funds, and also to avoiding the acceptance of non-permitted types of business as participants. Such a breakdown leads to reputational risk, as it may negatively affect the renewals of policies by existing policyholders, as well as the ability of the TO to attract new ones.

2. Fiduciary risk arising from misconduct or negligence (in the Shari'ah sense of these terms) in the performance of duties as mudarib or wakeel as a manager of the assets of underwriting funds and investment funds. In some structures, management of underwriting is also carried out under a mudarabah contract. In case of misconduct or negligence, a mudarib becomes liable for the capital of funds under its management.

3. The business risk of being unable to meet its operating expenses out of the fees it receives from managing the underwriting and the investments of the takaful undertaking.

TOs are not exposed to underwriting risks, as these are borne by the takaful risk funds, but have the same responsibilities as the managements of conventional mutual insurers as regards the management of the risks. They will have to face challenges in managing a takaful undertaking's risk exposures in adequately defining, identifying, measuring, selecting, pricing, and mitigating risks across business lines and asset classes. The management of these risk exposures is a continuous process that is a key aspect of the implementation of the strategy of the undertaking. It should be characterized by an appropriate understanding of both the nature and significance of the risks to which the undertaking is exposed, and also the Shari'ah rules and principles by which the TO and the participants are contractually bound.

In addition, the relationship between a TO and takaful participants allows, in practice, for a number of different contractual arrangements between them, the two most widely used being wakalah and mudarabah. Such differences affect the ease of comparison between differing takaful undertakings, as well as between takaful and conventional insurance undertakings, either proprietary or mutual, although as noted above a takaful is closer to a conventional mutual.

9.2 COMPARISON BETWEEN CONVENTIONAL INSURANCE AND TAKAFUL

From an operational point of view, the key differences between conventional proprietary insurance and takaful are as follows:

1. Proprietary insurance is concerned with risk transfer, insured risks being transferred from the insured to the insurer in return for a premium; whereas takaful is concerned with risk pooling, whereby the policyholders (takaful participants) mutually insure one another in a common risk pool financed by their contributions (premium payments).

2. The investments of funds in a takaful undertaking must be Shari'ah compliant, as must any activities the risks of which are insured.

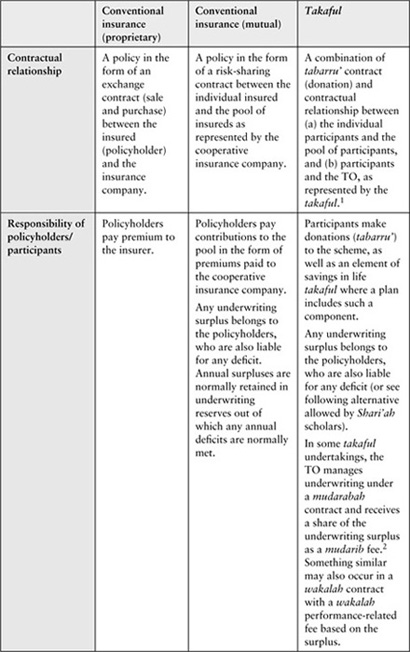

A comparison between conventional insurance and takaful provides distinct characteristics that cast light on the risk profiles of takaful undertakings. In particular, the relationships between a TO and takaful participants as highlighted in Table 9.1 are unique to takaful undertakings, given that the takaful participants are not insured as in conventional proprietary insurance, but share the profits and bear the deficits of the takaful undertaking in a manner similar to conventional mutual insurance. In other words, while takaful participants are in a position comparable to policyholders in mutual insurance, the TO plays an important role that the management of a conventional mutual does not play in the event of a periodic deficit in a takaful fund that exceeds the reserves of the fund, thereby making it potentially insolvent. In such a case, the TO acts as a lender of last resort by providing a qard (interest-free loan) to the takaful fund. Such a loan will be repaid out of future underwriting surpluses.

Table 9.1 Comparison Between Conventional Insurance (Proprietary, Mutual) and Takaful

A similar comparison may be made between life products from conventional life insurance providers and life or family takaful undertakings (healthcare plans being typically provided by the latter). In both conventional mutuals and takaful, investment profits belong to the policyholders, except that, in takaful, the operator may share in these profits as a mudarib or by virtue of a performance-related wakalah fee for fund management. There are also some products (such as “whole life” cover and “defined benefit” pensions) that takaful does not offer, as they are not Shari'ah compliant due to the impermissible degree of gharar (uncertainty) inherent in “whole life” cover and the impermissible element of guarantee in “defined benefit” pensions. “New for old” in general takaful is similarly not acceptable, as it would constitute a form of gambling, or maisir.

9.3 FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES OF TAKAFUL FROM A RISK MANAGEMENT PERSPECTIVE

As can be seen from the above analysis, the economic nature of takaful undertakings is broadly similar to that of conventional insurance undertakings (proprietary and mutual), albeit that modern-day takaful is a hybrid between a Shari'ah-compliant mutual structure for participants (policyholders) and a Shari'ah-compliant management company—namely, the TO. Both types of undertaking receive premium contributions and investment income, pay claims, maintain reserves, have assets and liabilities, and so on.

However, in addition to the differences mentioned in the preceding section, the following points should be noted:

- In takaful undertakings, Islamic legal contracts are the basis of the relationship between the TO and the policyholders.

- Due to the relationship between the TO and participants being based on either a wakalah or a mudarabah contract (or both), the TO's responsibility is to manage the operations, including underwriting and investment, and to settle claims, on behalf of the participants.

- Tabarru', or the donation principle, is a concept of fiqh al-muamalat that is fundamental to takaful schemes. Tabarru' refers to the basis on which the takaful participants willingly make a contribution for the benefit of all the participants in the takaful who are entitled to such benefits.

- Conventional insurance business involves the element of riba where the investments include (as they commonly do) investments based on riba. This is even more the case for savings products, where the benefit to the policyholder, rather than being compensation for a loss sustained, is the investment return. Hence, it is important that investments of both the takaful funds and the TO shareholders' funds are riba-free types of investment. Moreover, takaful undertakings do not charge interest for delay in meeting premium payments, as interest is riba and thus prohibited by the Shari'ah.

- The nature of mitigating risks: takaful undertakings should use retakaful undertakings to cede risk exposures. However, where the retakaful is unavailable, the Shari'ah board may allow takaful undertakings to use conventional reinsurance until the retakaful undertakings become available (see Chapter 8 in this volume).

9.4 RISK ISSUES IN TAKAFUL UNDERTAKINGS

9.4.1 Introduction

Given the above distinct characteristics of takaful, the analysis of risks inherent in a takaful undertaking can be done in two ways: (a) balance sheet; and (b) the contractual relationship between the TO and takaful participants.

Due to the different contracts and contractual ties that govern relations between the TO's shareholders, its board of directors and management, and the takaful participants, the takaful structure in the balance sheet is generally split into two—or, for family takaful, three—broad categories of funds:

- shareholders' funds (consisting of the TO's own capital and reserves);

- in family takaful, participants' (or policyholders') investment funds (Depending on whether there is a linked investment component, such a fund is built up from a specified proportion of the total premium contributions paid by the participants which is treated as a savings- or investment-linked portion); and

- risk or underwriting (takaful) funds, which are built up from the remaining portion of the premium contributions paid by a participant for the benefit of mutual protection of members in the event of a covered loss suffered by the participant or any other member.

There are many ways in which risks can be described and understood. It is important not to restrict these to a single risk definition, as certain definitions may be appropriate in certain contexts. With some exceptions, the risk profiles of the takaful undertaking are generally similar to those of conventional insurance operations, especially mutuals, because these exposures are inherent in both types of insurance undertaking. Both takaful undertakings and conventional insurance companies operate on the principle of risk pooling (and the law of large numbers), whereby the risk pool assumes the risks that the insureds do not want to bear themselves. Takaful undertakings as well as conventional insurers have a competitive advantage in managing these risks, thanks to their expertise in the assessment and handling of these risks and in the management of risk portfolios.

In relation to the above three types of fund, a TO will structure the investment portfolio based on the different characteristics and objectives of each fund. In dissecting the risks associated with each fund, the operator needs to bear in mind, among other things, the following questions:

- What expenses can be charged to the fund?

- Who absorbs losses or underwriting deficits if these occur?

- What happens to underwriting surpluses, and who benefits from such surpluses?

Different answers to these questions will result in different exposures to risks or degrees of such risks. For example, both shareholders' funds and policyholders' funds are generally exposed to investment risk. While risk funds are also exposed to investment risk, they are also exposed to liquidity risk as a result of a maturity mismatch between assets and liabilities when claims occur.

In general, the takaful undertaking is exposed to two broad categories of risks that affect policyholders: (a) underwriting risk arising from the issue of the policy; and (b) investment risk arising from investment portfolio of assets (of different funds). The TO, in turn, is exposed to operational, fiduciary, and business risks, as described above.

9.4.2 Underwriting Risk

Underwriting or actuarial risk is the risk that arises from raising funds via the issuance of insurance policies and other liabilities. Since the pricing of the conventional insurance policies reflects not only expected losses but also the yields an insurer can earn on the funds between the inception of a policy and its termination or the payment of benefits, the investment yield rate assumption used in developing insurance prices (premium levels) is of critical importance. First, forward interest rates cannot be synthesized to lock in a spread, because the insurer has no way of knowing if future periodic premium payments will be forthcoming. Second, the loss distributions can undergo substantial evolution over time, as more information is revealed and as the economic environment changes.

Exposure to underwriting risk in a takaful undertaking is similar to that in conventional insurance. The takaful operator determines premium (takaful contribution) levels in accordance with actuarial principles and practices based on standard statistical techniques.

The takaful undertaking is also expected to have a well-diversified risk portfolio in terms of industry, geography and business lines, and appropriate underwriting decision making. In practice, the takaful undertaking may run the risk of the operator ignoring underwriting advice, and hence, offering a low level of premium contribution in order to obtain business. While a conventional insurer could do this, as the company is exposing its own capital, a takaful operator has no right to expose the takaful fund to such a commercial decision in ignoring underwriting advice. To do so would constitute misconduct or negligence, and would give policyholders the right to make a claim against the takaful operator if the takaful fund became insolvent.

Another aspect of actuarial risk is that, in any given period, the total of valid claims (underwriting losses) may lie outside the upper level of those projected. This could happen for two reasons. First, the projection may be based on an inadequate knowledge of the loss distribution. Second, the losses may lie within the loss distribution but exceed the takaful operator's expectations in the normal course of business because they are at the upper extreme of the loss distribution, which in principle, would be extremely rare. The degree to which total losses deviate from the mean of the loss distribution depends on the shape of the loss distribution, which depends on the nature of the risks insured.

General and family takaful undertakings3 are exposed to underwriting risks that are similar to those of their counterparts in conventional insurance. This is natural, as takaful aims to provide Shari'ah-compliant substitutes for conventional insurance products, including pension plans, medical and healthcare plans, and educational plans.

For general takaful, the underwriting exposures relate to natural and man-made disasters and third party liability. These exposures undertaken by takaful undertakings include those from both retail (household) and corporate market segments. Natural disasters include earthquakes, storms, and the like, while man-made catastrophes include crashes and fires. Third party liability includes product, employers', and general liability.

In family takaful, since the mortality rates are relatively stable, the underwriting risks are fairly predictable. Financial underwriting in family takaful also reduces risk to appropriate risk coverage levels. General takaful exposures include catastrophes such as epidemics, major accidents, or terrorist attacks.

In both general and family takaful, the operator is exposed to the risk, stemming from uncertainty about future operating results relating to items such as investment income, mortality and morbidity, frequency and severity of claims and losses, administrative expenses, sales and lapses. If a takaful's pricing is based on assumptions that prove inadequate, the fund is exposed to the risks of not being able to meet participants' obligations. Due to the varying contractual relationship between the operator and participants in respect of underwriting, which is based on either a wakalah or a mudarabah contract (the former being more generally accepted, for reasons explained in earlier chapters), the risk severity may vary from one takaful undertaking to another.

In family takaful pension plans, there are no guarantees (that is, they operate on a “defined contribution” rather than a “defined benefit” basis). This implies that the risk profile may be different from some conventional life insurance products, where guarantees may be given in terms of the amount of the annuity that will be payable as a pension.

In addition, the solvency of a takaful undertaking needs to reflect the location of risk. If there is a deficit in the takaful fund, the TO may run the risk of having to make an interest-free benevolent loan (qard) as a regulatory requirement to meet its obligations. This raises practical issues of whether liability can be extended to participants' investment accounts because, contractually, the participants share in any surpluses and, in principle, meet any deficits in the underwriting pool. However, their investment accounts may (and arguably should) be “ring fenced” against such an eventuality. In this respect, there is a need to determine the participants' shares of any deficit and how such shares will be contributed. At present, TOs have different practices. For example, in the case where a family takaful product has a combined element of savings (in an investment fund) and protection (in a risk fund), there may be a possibility of encroaching on the investment fund should the risk fund run into deficit. In the case of a general takaful product, which has only an element of protection, especially general accident products, the risk fund is exposed to a potential deficit during a period and the policyholder may choose not to renew the policy for the next period.

9.4.3 Investment Risk

Since investments must be Shari'ah compliant, a takaful firm cannot invest in conventional interest-paying bonds or certain categories of equities (brewers being an obvious example). There are also limitations on the use of derivatives. The asset risk profile is, therefore, different from that of a conventional insurer.4

The assets side of the balance sheet consists mainly of Shari'ah-compliant equities, real estate, sukuk, and profit-sharing investment accounts with Islamic banks, the latter being used to manage liquidity risk (see Chapter 11). Equities and real estate are volatile asset classes, so that takaful undertakings are typically exposed to market risk in respect of such assets.

“Market risk” refers to the possibility of loss on a portfolio because of adverse movements in the foreign exchange rates, benchmark rates, and other market prices. This aspect of risk is important when considering investment risk in the asset side of the takaful undertaking's balance sheet. However, for certain types of asset (such as ijarah assets and ijarah sukuk), credit risk may also be important. The takaful undertaking may build certain portfolios of takaful funds for strategic reason. A limited range of permissible asset allocations may lead to concentration of risks in these portfolios.5

Takaful undertakings, like conventional insurers, face a combination of asset risk (market and, possibly, credit risk) and risk arising from actuarial liability value changes associated with systematic factors. In general, every takaful operator faces a different exposure to its portfolio, depending on the portfolio's risk mix. A takaful operator must also decide which risks to accept on behalf of the risk fund, how to deal with agents or brokers, and what risks to reinsure/retakaful. In doing so, a TO builds up the portfolios of risks by achieving risk diversification through accepting a large number of policies whose individual risks are not correlated, and hence, tend to cancel each other out on aggregate. As such, the risks in the portfolio of policies can be naturally hedged up to a point, but cannot be diversified completely away, as there will always remain some positive correlations between risks, and negative correlations are unlikely.

In general, the Islamic financial services industry is still facing a great shortage of asset classes that comply with the Shari'ah rules and principles. Despite efforts by the central banks and others to provide a range of liquid instruments, with the exception of investment accounts with Islamic banks which tend to be low yield, short-term instruments (such as short-maturity marketable sukuk), in which the institutions offering Islamic financial services including takaful can place their surplus cash and earn good returns, are still scarce. In addition, long-term asset classes that comply with the Shari'ah rules and principles (for example, real estate and long-maturity sukuk) do not have liquid secondary markets and institutions tend to hold the assets until maturity. Consequently, a takaful undertaking faces the risk associated with the appropriate investment allocation and liquidity management of the takaful funds.

“Liquidity risk” relates to the potential inability of the takaful undertaking to liquidate assets (such as real estate) if and when required to meet claims and other obligations. Liquidity risk may arise in a stress situation because the TO may not be able to liquidate assets located in another jurisdiction since the government in that jurisdiction has restricted the ability of the operator to freely unwind the investment.

9.4.4 Relationship between the Takaful Operator and Takaful Participants

Another way of viewing the risks specific to takaful, with particular reference to the risk exposures of the TO, is through decomposition of contractual relationships for different activities. This provides different perspectives on the risks associated with the obligations of the TO and takaful participants that need to be considered in order to clarify issues in the takaful undertaking. These are set out in Table 9.2.

Table 9.2. Comparison Between Mudarabah and Wakalah Contracts

| Mudarabah | Wakalah | |

| Underwriting |

|

|

| Investment |

|

|

| Management expenses |

|

|

The following observations can also be derived from the above. First, be it a mudarabah or a wakalah contract, the TO is not liable for any deficit or loss suffered by the takaful fund as it is not the owner but only the custodian of the takaful funds, unless the loss or deficit is proved to be attributable to an act of misconduct or negligence on its part. The operator is exposed to a form of business risk (withdrawal risk—that is, participants not renewing their contracts) if the takaful funds are in deficit and the participants realize that they are bearing the deficit. This may result in the TO not receiving sufficient management fees to cover its expenses.

Second, although the above two contracts involve differences in approach, the accounting treatment and disclosure issues which arise are common. These include, among other things, segregation of assets, liabilities, income, and expenditure between the TO and the policyholders' funds (takaful underwriting funds and, where relevant, investment funds), setting aside reserves for meeting outstanding claims, future claims (from accepted risks), and contingencies in the process of ascertaining surplus or deficit in the underwriting funds.

Third, the fact that the management of the takaful undertaking is appointed and instructed by the TO's shareholders rather than the takaful policyholders raises the issue of various conflicts of interest, as the management of the TO operator would arguably be reporting to two sets of “principals” and would be under pressure to favor its own shareholders rather than the policyholders in the event of such conflicts, as highlighted in Chapter 4. In present-day takaful, there is very little in the way of policyholders' rights to oversight of the management of the operation. The Islamic Financial Services Board has issued a draft standard on the governance of takaful which addresses this issue.

As a result of the above analysis of the contractual relationship between the TO and the policyholders, it can be seen that some of the risks to which the TO is exposed are comparable to those of an asset management firm providing fiduciary services to its clients. TOs operate within a broad and complex risk environment. The most obvious risks are created by or arise out of specific agreements between the TO and policyholders, legal documents, investment portfolio strategies, laws and regulations, court rulings, and other recognized fiduciary principles. Other risks, which are more subtle but are potentially as dangerous, arise from the manner in which the TO markets itself, the quality and integrity of the individuals it employs, and the type of leadership and strategic direction provided by its board of directors and senior management.

The potential for loss, either through direct expense charges or from loss of participants (withdrawal risk), arises when the operator fails to fulfill its fiduciary and contractual responsibilities to participants, shareholders, and regulatory authorities. Significant breaches of fiduciary and contractual responsibilities can result in financial losses, damage an operator's reputation, and impair its ability to achieve its strategic goals and objectives.

9.5 MANAGEMENT OF RISKS IN A TAKAFUL UNDERTAKING

9.5.1 Introduction

A takaful operator is required to manage risks at two levels:

- underwriting and investment risks of the takaful and policyholders' investment funds; and

- the fiduciary, business, and operational (including Shari'ah compliance) risks to which the TO itself is exposed, as well as the investment risks of any assets in which the shareholders' funds are invested (see Chapter 11).

With regard to underwriting risks that are to be borne by the takaful (risk) funds, the TO is responsible for managing these risks by exercising due diligence in accepting such risks, avoiding risk concentrations, setting premium contribution levels that properly reflect the risks being underwritten, and making appropriate use of retakaful (or if this is not available, reinsurance).

The risk management of both levels can be overlapping, since the risks may spread from one level to another. For example, poor management on the TO's part may be difficult to identify as a root cause of poor underwriting results or investment performance. In principle, while the TO is not directly exposed to underwriting risk, it may be indirectly exposed through a requirement to provide a qard if an underwriting fund cannot meet its obligations. Nor is the TO directly exposed to investment risk on the participants' funds. This being the case, in view of the overlapping nature of the risks mentioned above, the objectives of risk management in takaful include the following:

- To address conflicts of interest among the stakeholders: The TO needs to have effective fiduciary risk management practices in respect of the relationship between itself and the policyholders.

- To protect the safety of the takaful funds and/or to meet the expected rate of return on investment: The TO needs to have effective underwriting (actuarial) risk and investment risk management practices in understanding and managing the risks in retained or reinsured exposures and increasingly illiquid products, and in limiting or hedging exposures to credit and market risk.

- To ensure all funds are sufficient to pay claims and obligations and to be able to withstand adverse conditions: The TO needs to have effective liquidity risk management practices in assessing its vulnerability to that risk in a stressed environment and taking appropriate action.

Notwithstanding the above objectives, a key aspect of managing risk is that the TO should ensure that the Shari'ah rules and principles are observed at all times in meeting such objectives. This is to ensure the good reputation of the TO and business continuity.

In this respect, the TO needs to have the necessary tools and procedures for applying effective risk management practices, including those that are common to all insurance undertakings and those that are unique to takaful. The management of a takaful undertaking relies on a variety of techniques in their risk management systems. The techniques employed by conventional insurers are equally applicable in this respect. Four elements have become key steps in implementing a broad-based risk management system:

- standards and reports;

- underwriting authority and limits;

- investment guidelines or strategies; and

- incentive contracts and compensation.

These tools are established to measure risk exposures, define procedures to manage these exposures, limit exposures to acceptable levels, and encourage decision makers to manage risk in a manner that is consistent with the undertaking's goals and objectives.

Nevertheless, as market events progress, other weaknesses may emerge, and the following observations may not prove to be definitive or complete in managing the risks associated with both levels—the takaful policyholders' funds and the TO itself.

9.5.2 Managing Fiduciary Risk in Takaful Undertakings

As has been said earlier, TOs must duly observe their fundamental obligations toward their participants (policyholders), particularly with regard to compliance with Shari'ah rules and principles. Shari'ah governance must remain an inherent feature of TOs, since the raison d'être of takaful is the offering of a protection scheme that complies strictly with the requirements of the Shari'ah. In this regard, as already noted, the IFSB has already set up a separate working group dedicated to developing standards and a framework for Shari'ah governance.6

In a takaful undertaking, there can be different contractual obligations for the underwriting and investment. Contractually, the policyholders aim to provide the TO with a mandate related not only to the contribution for insurance protection but also to the assets in which the TO is expected to invest on their behalf. The contracts also reflect what the TO is remunerated to do: to manage the underwriting and investment activities on behalf of the policyholders. Hence, the TO is expected to manage the risks arising in two mandates. In view of this, the TO may apply risk management elements either separately or in combination. It is important, therefore, for the TO to have adequate knowledge of the technical provision requirements, policyholders' expectations, and (in family takaful) their risk appetite in regard to their investment fund.

In managing the fiduciary risks in a takaful undertaking, it is possible to decompose these risks into the following categories: underwriting risk and investment risk (including market, credit, and liquidity risk). However, these risk classes are not mutually exclusive elements of fiduciary risk. Instead, they often overlap. It is important, therefore, to have an understanding of the components of fiduciary risk as well as aggregation of these components with the aim of minimizing the risks for takaful participants.

9.5.2.1 Underwriting Risk

In light of the above discussion on the identification and measurement of risks, how can the underwriting risks be managed and controlled? Since the takaful undertaking is based on specific Shari'ah-compliant contracts—that is, wakalah or (more rarely) mudarabah—with the takaful participants, the TO needs to manage these risks from both contractual and prudential perspectives.

The TO must ensure that Shari'ah principles relating to equity and fairness are applied. All policyholders should be viewed as “equal” at the point of entry. The TO may, however, increase the contribution level (premium) for some of the policyholders with poor claims records, to avoid undue strain on the takaful fund.

Nevertheless, the takaful fund may suffer from an unexpected level of losses, and therefore, lack the resources to pay claims. For the management of risk associated with the underwriting exposure within the contractual obligations in the takaful undertaking, the policyholders need to know how the TO will deal with such a situation.

- If the business is wound up in this situation, participants do not have access (recourse) to assets of the TO unless there is misconduct or negligence on the part of the TO. In jurisdictions where regulatory authorities require such access in order for solvency requirements to be met, do policyholders have priority over other creditors in this case?

- Is a qard compulsory? What are the terms of this interest-free loan? Would this compulsion be legally effective given existing statutes?

- To what extent is capital fungible between takaful funds? What happens if the TO suffers unexpected losses and cannot meet its obligations when there has been misconduct or negligence on its part?

- Is support permitted from the takaful policyholders' funds to the TO? What controls would there be over this?

- If the TO is wound up, would assets of the takaful policyholders' funds be “ring fenced” against the claims of the creditors of the TO?

Even if the policyholders are formally liable to meet calls to provide additional funds to meet underwriting deficits, it is not clear that such an obligation is effectively enforceable. The regulatory authority may be reluctant to oblige policyholders to pay such calls, as this may give rise to massive withdrawals (non-renewals) by policyholders so that the fund is no longer a going concern.

Product documentation of the specific TO may allow a set-off between takaful funds for the various products that are offered. In this case, the TO can manage underwriting deficits more easily than when such a set-off is not permitted.

Underwriting procedures remain very important for a TO, to ensure that risks accepted by the TO for the takaful fund are paid for by an appropriate level of premium contribution. The typical takaful undertaking faces difficulties of moral hazard and adverse selection that are no less significant than for conventional insurers. There is a need to assess the underwriting procedures and consider whether there are any restrictions (legal, regulatory, or social) which affect the TO's ability to decline risks for renewal or to adjust the contribution level for takaful cover.

9.5.2.2 Investment Risk

The TO uses a number of techniques in managing the market risk of different fund portfolios either individually or in aggregate. These techniques, which are available for asset management in conventional insurance, are equally applicable in a takaful undertaking, subject to Shari'ah restrictions on investment.

Related to market risk is the potential for assets with no active secondary market (including thinly-traded shares and unlisted sukuk, as well as real estate) to be incorrectly marked-to-market. It may be possible that some funds receive favorable treatment compared to other takaful funds. In this regard, the relevant controls include an independent pricing group and close management scrutiny of such assets.

The TO may have an asset allocation policy that requires some assets to be pre-allocated to specific takaful funds before they are acquired. It may be possible for the takaful undertaking to mitigate specific liquidity exposures by establishing strict rules on the types of assets that can be held in takaful funds. Importantly, investment in illiquid assets should be monitored and limits placed on exposures to such assets. Market liquidity and exposures to certain assets should be monitored.

9.5.3 Managing Risks Relating to the TO

9.5.3.1 Governance and Operational Risk

Apart from the fiduciary risks mentioned above, the risks relating to the TO can be broadly categorized into governance risk and operational risk. Governance risk is, however, related to fiduciary risk and concerns the oversight of the management of the takaful funds, in underwriting and in investment, for both of which the takaful operator is directly responsible. It is assumed that the role of the oversight by the board of directors and senior management is to assess and respond to changes in the risks. The TO's board of directors, management, and all personnel are expected to provide reasonable assurance of effectiveness and efficiency of operations, reliability of financial and non-financial information, an adequate control of risks, a prudent approach to business, and compliance with laws and regulations, and internal policies and procedures.7

Operational risk in the takaful undertaking is inherent in every decision that is taken and every process that is implemented by the TO. Although many of the risks that fall within this category will initially affect the takaful funds, and therefore, the participants, ultimately the operational risk will affect the TO itself.

Management of the takaful undertaking can expose the TO to potential financial loss through litigation, fraud, theft, lost business, and wasted capital from failed strategic initiatives. Losses from the takaful undertaking's activities typically result from inadequate internal controls, weak risk management systems, inadequate training, or deficient board and management oversight. Maintaining a good reputation and a positive public image is vital to the success of a takaful undertaking and to the reputation of its TO.

9.5.3.2 Reputational Risk

Takaful presents itself as an alternative to conventional insurance that is compatible with Islamic ethics. As has been mentioned previously, an overriding concern of risk management is that the TO should ensure that it observes the Shari'ah rules and principles, which include ethical aspects of meeting its business objectives at all times. In this respect, the management of this risk would call for a number of controls in order to ensure upholding the reputation of the TO and the continuity of its business activities.

The takaful normally draws on in-house or external religious advisors, commonly known as a Shari'ah board. In doing so, the takaful operator is conveying to participants, either explicitly or implicitly, that its operations are in accordance with Shari'ah rules and principles.

In addition, the TO may require that all staff be trained in key business policies and procedures that require observation of Shari'ah rules and principles. The operator may include know-your-customers and anti-money-laundering-and-terrorism systems to enhance the processes for early detection. In addition, the staff may be required to sign a code of conduct on a periodic basis. There are also periodic Shari'ah internal reviews.

9.5.3.3 Compliance Risk with Regard to Shari'ah Rules and Principles and Regulatory Requirements

Related to reputational risk is compliance risk. There are two aspects to compliance risk. The first aspect relates to the risk that the takaful undertaking does not comply with the Shari'ah rules and principles. Second, there is a possibility that the TO does not properly adhere to the prudential requirements (for example, regarding solvency) and industry standards of practice.

In attempting to control these types of risk, the TO needs to ensure its staff can manage Shari'ah and other restrictions in the process of acquiring, as well as maintaining, the policyholder in the undertaking. The TO is also responsible for educating the policyholders so that their expectations regarding risk, cover, and benefits are properly in line with the contracts.

The next step in controlling the risk of failure of compliance is to have in place formal systems and procedures for monitoring compliance with the Shari'ah and with regulatory requirements. In the case where traded securities are being periodically reviewed for compliance by Shari'ah national authorities, the TO needs to have an updated specific list of permissible securities from the authority and to observe the period within which funds need to divest prohibited ones.

The other risk associated with compliance risk is the adherence to laws and regulations. This is an issue particularly for a TO that operates in a number of jurisdictions or that can invest its funds in other jurisdictions. What is accepted by Shari'ah rules and principles in one jurisdiction can be prohibited in another. An understanding of all prudential environments as well as Shari'ah rulings is the control against this type of risk.

9.5.3.4 Business Continuity Risk

Like other institutions offering Islamic financial services, a TO needs to manage its business continuity risk. This is the risk that the continuity of the business is threatened by, for example, the loss of senior officers. There is a clear shortage of skilled staff having knowledge of both Shari'ah compliance and insurance.

In mitigating this risk, TOs may spend considerable time and resources on developing business continuity and key personnel plans. This is done by identifying key individuals such as in the area of actuarial science and Shari'ah, and ensuring that their knowledge is not shared with competitors. In addition, the TO operator may develop a succession plan.

In the fast-growing industry of Islamic finance, in general, TOs face the pressure of undertaking growing volumes and facing increasing competition. The number of new entrants in the market is increasing. Staff retention becomes very challenging and may contribute to growth in expenses.

This chapter has examined the distinction between the need for appropriate risk management in takaful undertakings, including the risks of the takaful funds and those of the TO itself. In view of the similarities between certain aspects of managing takaful undertakings and asset management, the management of risk associated with a takaful undertaking may borrow the risk management techniques of asset management firms.

While the risks inherent in the takaful funds and in the TO itself may overlap, the control for each level of risk can still be addressed through specific mechanisms. The objectives for takaful fund performance and risk management at both levels make it necessary for the TO to manage all these risks at the same time.

In the context of the new evolving takaful industry, the innovation and evolution of risk management practices occur continuously on an incremental basis. Hence, a key ingredient of best practices in management of the risks in the takaful undertaking, including the takaful policyholders' funds and the TO itself, is that the TO feeds its “lessons learned” back into its own ongoing risk management processes.

Notes

1 Certain jurisdictions have chosen the contractual relationship based on cooperatives and waqf (generally categorized as the “pure” non-profit model), and others have opted for mudarabah or wakalah (profit model). The remaining discussion in this chapter focuses on the profit model.

2 There are doubts as to the Shari'ah compliance of an arrangement whereby the TO shares in underwriting surpluses as mudarib, since in a mutual structure an underwriting surplus is not a profit and to treat it as such is redolent of proprietary insurance which is just what takaful is designed to avoid. (See Chapters 2 and 3 in this volume.) However, based on discussion among Shari'ah scholars, they cast much less doubt on a wakalah performance fee being applied to surplus generated on behalf of the TO.

3 General and family takaful are, broadly speaking, the Shari'ah-compliant counterparts of conventional general and life insurance.

4 Note that the make-up of the investment portfolio will vary among takaful undertakings, due to variations in risk profiles and perception of market trends.

5 The exposure to concentration of risks on investments does not apply to unit-linked investments, where the participants bear all exposures, which are not shared with the takaful operator.

6 For further discussion on the management of governance risk, refer to Chapter 4 and the IFSB Exposure Draft of Guiding Principles on Governance for Islamic Insurance (Takaful) Operations.

7 A detailed discussion on the management of governance risk in takaful undertakings can be found in Chapter 4. See also, on this topic, the IFSB's Exposure Draft on Guiding Principles on Governance for Islamic Insurance (Takaful) Operations and the IFSB's Exposure Draft on Guiding Principles on Shari'ah Governance System.