Explore Environmental and Structural Hazards

Cryptocurrencies have challenges from within about how they operate, scale, and resist attack. They also have external costs and threats that are incidental to the value created, but have a cost to individuals, companies, societies, and the future of humanity.

If you are someone considering or participating in cryptocurrency, I would try to convince you that there’s an ethical and societal duty to consider the first of these, which is resource consumption, led largely by running through huge amounts of electricity to no good purpose.

The second category encompasses a broader variety of threats to the value and viability of cryptocurrency, and you should understand as part of the risk you assume if you trade, accept payment, or create contracts with Bitcoin, Ethereum, or other digital coin.

I end the chapter with ransomware, which might seem completely off base. But the increased scale of blackmail paid with cryptocurrency means governments may try to reduce the partial anonymity of cryptocurrency and crack down in many other ways to reduce the impact ransomware has on the smooth functioning of national economies.

Resource Consumption

Nearly all cryptocurrencies that are valued in fiat currency at any significant level currently rely on massive amounts of computation via proof of work (see Proof of Work). To create that proof, Bitcoin and others burn through the equivalent of a modest-sized European nation’s worth of electrical energy, most of it non-renewable.

That’s bad enough to start with. But the methods by which most digital coinage operates provides an incentive to each party engaged in mining to increase their computational power. In a zero-sum game, people are trying to grab as big a piece of the pie as they can profitably, and with cryptocurrency that’s a race to burn up the Earth.

But cryptocurrency can also burn through hardware because of the intensive use that mining places on it.

Fortunately, there are some countervailing trends that may put a little drag on the tendency towards wanton pointless destruction.

Electricity

If you don’t believe that climate change is significantly driven by human industrial activity, you may want to skip to the next chapter. (But you should also read NASA’s briefing on the subject, which explains in plain terms why we are largely or entirely responsible.)

Bitcoin by itself consumes an estimated 125 terawatt-hours (tWh) of electricity each year, which is about 0.6% of all electricity used worldwide, and similar to Norway or Pakistan’s annual consumption (Figure 9). That powers a system valued under a trillion dollars and which processes tens of millions of transactions each year.

It’s difficulty to get a comparable energy-consumed number for the global financial system, if one factored in all banks, the printing of money, shipping checks, running servers, the gas for people driving around filling ATMs with money, and so forth.

Digiconomist estimates a Bitcoin transaction uses a million times more electricity than a credit-card transaction. Even factoring in the larger financial services footprint, Bitcoin is still many thousands of times less efficient than a corresponding electronic one—and those numbers are out of date.

Defenders of cryptocurrency’s electrical and carbon footprint often justify it by pointing to the conventional banking and payment world. Yet the global financial system as a whole serves over 7 billion people, with the assets of financial institutions alone being over $400 trillion. In just the United States in 2018, there were over 130 billion payments made by card—credit, debt, prepaid, and EBT (federal payments of various kinds)—totaling over $7 trillion.

Even if this system worldwide consumed as much as all cryptocurrency taken together, it could be seen as a necessary tax on the ability to conduct domestic and global business electronically, and produce huge savings elsewhere.

Fundamentally, the greatest rejoinder to any defense of many terawatt hours of annual power consumption is that it’s meaningless. There’s no inherent requirement in Bitcoin or any cryptocurrency to be so wasteful. The baseline required to run the list is a tiny, tiny fraction of that.

As Twitterer “hafthor” aptly—and hilariously—summarized in a recent exchange about cryptocurrency’s energy usage:

…it’s not just the energy the winner used to mine the coin to record the transaction, but the combined energy of all the losers that have to restart their hunt for magic hashes.

The rest is the result of an epiphenomenon, an accidental side effect of overconsumption resulting from a lack of prognostication power by Bitcoin’s creator(s) as to the amount of money and hardware people would deploy in a race to the top.

The heedlessness reminds of a scene in a Law & Order episode in which a rich man is accused of (and ultimately found guilty of) hiring someone to steal someone’s kidney to save his daughter’s life. The daughter tries to persuade the district attorney that the man whose organ was stolen would be fine—they were going to pay him off. The assistant DA’s rejoinder:

But, Ms. Woodleigh, do you really think your father would have acted any differently, if you had needed a heart instead of a kidney?

Bitcoin miners would gladly use 100% of the Earth’s electrical output if they could.

Hardware

Most cryptocurrency consensus generation—mostly proof of work—is exceedingly wasteful on hardware, too. Bitcoin moved from CPUs (computer processors) to GPUs (specialized processors in graphics cards) to FPGAs (the obscure Field-Programmable Gate Arrays) to ASICs (custom-designed chips), with equipment being sold for scrap or abandoned in the race to the top.

Hundreds of thousands to millions of servers continuously run full out mining Bitcoin, Ethereum, and other currencies in challenging conditions, and are constantly burning out and being replaced. No one has a real grasp of the waste there.

In the first quarter of 2021, one aspect emerged as the peak price of cryptocurrencies of all sorts led to a silicon chip shortage. The Financial Times wrote:

Automakers including Toyota and Volkswagen have slashed production of cars as a result. Smartphone makers are delaying launches of new models. A shortage of gaming chips has forced chipmaker Nvidia to programme a new chip to throttle mining efficiency by half when it detects it is being used to mine cryptocurrency.

But the Chia cryptocurrency brings a whole new sense of scale to pointless use of hardware for arbitrary results. Chia relies on a form of proof of space to determine the right to create blocks and obtain rewards (see Proof of Space).

When the coin became its production rollout in May 2021, the demand for SSDs and hard drives became so great, it constrained storage availability worldwide. This caused shortages for computer manufacturers and a substantial, though temporary, rise in prices. The intensity of data writing led some SSD makers to declare use of their equipment for Chia voided the warranty, while a German hosting company, Hetzner, banned Chia (and other crypto mining) on its servers because they said Chia rapidly wore out their drives.

There’s always a new way to turn hardware into dross.

Rejecting Waste

Some designers of altcoins learned from Bitcoin and proof of work and built protocols intended to resist a race to the top and the maximum resource consumption.

Some picked algorithms other than the hashing one employed in Bitcoin for proof of work that don’t linearly scale above a certain amount of computational effort. These are often called ASIC-resistant proofs as they are intended to penalize miners or validators deploying ASICs (application-specific integrated circuits). ASICs are computer chips created to produce the fastest calculations of a proof’s algorithm. Cryptocurrency in this category includes the anonymity-preserving cryptocurrency Monero, Vertcoin, and Ravencoin.

Ethereum picked a memory-intensive algorithm better suited for general-purpose computing gear and GPUs. (GPUs are the processors used for graphics, including specialized ones in graphics cards for gaming and animation rendering.) GPUs aren’t cheap, but they are in the range of affordability for many more people serious about participating in cryptocurrency mining.

Despite that, people are clever and figured out how to mine their way to the top. Ethereum bloomed to use an estimated 50 tWh, or 40% of Bitcoin’s electrical consumption—and Ethereum’s total exchange value is almost exactly 40% of Bitcoin’s. D’oh!

As Ethereum continues its migration from proof of work to proof of stake, one of its biggest selling points is that the stake-based consensus mechanism requires relatively little computational power per computer and relatively few computers. (See Proof of Stake.)

It also limits participation in part by having a minimum stake of 32 Ether (currently about $90,000) per validator. Even if each validator were run on a separate server, it’s still an incredible small fraction of the Ethereum mining rigs today—not to mention Bitcoin ones.

The Ethereum Foundation, which fosters the cryptocurrency’s development, says proof of stake would reduce Ethereum electrical consumption by 99.95%. It’s impossible to validate that the change will be that large, but it will certainly be significant. The evolution of a power-friendly cryptocurrency might cause migration from Bitcoin to Ethereum, particularly as regulators clamp down on energy usage in some countries.

Forces of Change and Disruption

Cryptocurrency doesn’t exist in its own universe, however virtual and digital it may be. Pressures outside its bubble affect its exchange price and its viability.

A constant of the last decade-plus has been cryptocurrency advocates explaining that cryptocurrency is not, in fact, volatile. Meanwhile, see Figure 10. One could argue that the considerable rise in exchange-derived value of Bitcoin and nearly all cryptocurrencies shows that volatility evens out over time to “prove” that the inexorable path is upward. And yet—see chart.

The explanation for the rise and fall of cryptocurrencies valuations has to do with externalities, just like a stock or precious metal. The huge drop across all coins in May 2021 had many apparent causes:

A crackdown in China

New U.S. emphasis on reporting

A report from Tether, a stablecoin, about its actual cash holdings

The rush out of cryptocurrency through exchanges, which can act like a run on the bank, accelerating the trading value

The Coinbase exchange’s stock price drop—nearly 50% from its debut price in the public, before the cryptocurrency value crash

Tesla halting Bitcoin payments for its cars, shortly after saying it would accept them

Let’s look more at the first four of these events and a few others to understand the current and future risks cryptocurrencies face.

Governments Crack Down

Nature may abhor a vacuum, but governments abhor a lack of oversight over financial transactions. Take environmental damage and combine it with difficult-to-trace payments, and you have a perfect regulatory storm.

No two governments treat cryptocurrency in the same way, however. It’s more like identifying a point on a spectrum between an absolute ban on its use and welcoming with open arms.

With China and the United States being the world’s two largest economies by far, and representing 40% of economic activity between them, eyes turn to those nations in looking a cryptocurrency policy.

China

China has barely tolerated Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies since Bitcoin became to be an economic force a few years after its launch. A rise in its ostensible value in 2013 led the People’s Bank of China, the country’s central bank, to ban financial institutions from handling Bitcoin as currency.

The bank said at the time, however, “Ordinary members of the public have the freedom to participate in Bitcoin transactions as a kind of commodity trading activity on the Internet, provided they assume the risks themselves.”

However, in 2017, the government shut down exchanges and trading platforms, and the central bank said fundraising for initial coin offerings (ICOs) were illegal. In 2019, the central bank said it would shut access to foreign exchanges.

On May 21, 2021, the Chinese government’s financial stability and development committee said it would “crack down on Bitcoin mining and trading behaviors” as part of a broader set of policies. A 12% drop in Bitcoin exchange value followed the announcement.

Mining isn’t illegal nationwide, but it’s increasingly frowned upon. Low electricity prices in China make Bitcoin mining affordable alongside the ever-higher difficulty rates. But some miners receive illegally low-cost or free electricity, and others steal it.

Some Chinese provinces have an outright mining ban. These include Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, and (as of June 9, 2021) Qinghai. Sichuan province says miners must leave by September 2021 after shutting down 35 companies that consumed 5.2 gigawatt-hours of power annually—a tiny fraction of the over 100 tWh consumed worldwide, but still something.

Because of the difficulty adjustment in cryptocurrencies that use proof of work, any slack in mining capacity is taken up by making mining easier for those remaining. Miners who can’t use their gear often sell it—sometimes at absurdly low prices. Miners in countries outside China may purchase it cheaply and make it more affordable to beef up their capacity.

But if an effective ban on using cryptocurrency is coupled with a crackdown and elimination of legal mining, it’s going to have an impact on the cryptocurrency economy. Fewer parties will be able to earn, trade, and spend the virtual money.

United States

The United States has taken a much more hands-off approach with cryptocurrency, although that’s changing. The government considers virtual coin as a commodity, like oil or gold, and it’s taxed like property. Moving cryptocurrency in and out of fiat currency creates capital gains and losses on which tax is collected or (in some cases) deductions from tax can be made. This is true, too, if you make purchases or sell items entirely within a cryptocurrency without any conversion, just as if you paid someone in silver based on the current trading value of silver.

For many years, anyone receiving $10,000 or more in cash had to file a form with the IRS and the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. In May 2021, the Biden administration made clear that they would require that kind of reporting for businesses receiving cryptocurrency of the same amounts.

The United States seems unlikely to prevent the use of cryptocurrency, but it’s clearly on the path to regulate and track it more precisely to avoid losing out on tax revenue, and to put more effort into preventing its use for criminal purposes. A May 2021 report from the U.S. Department of the Treasury noted, “Cryptocurrency already poses a significant detection problem by facilitating illegal activity broadly including tax evasion.”

The True Value of Tether Emerges

As noted in the section explaining cryptocurrency, Tether is a stablecoin (see Stablecoins). Each unit of Tether is allegedly backed by $1 of cash or cash equivalents. Or so said the organization running Tether, Tether Ltd.

Tether has weathered a large number of storms, many of which revolve around whether it is managing its assets with appropriate responsibility and whether it actually has the cash reserves that form the basis of its ostensible stability.

In April 2019, the New York Attorney General’s office filed suit accusing Tether Ltd. of shifting $850 million in funds to a sister corporation, Bitfinex, in opposition to the promises made in its de facto charter. (Tether Ltd. and Bitfinex are controlled by iFinex.)

The lawsuit was settled in February 2021, with the Attorney General stating bluntly, “Tether’s claims that its virtual currency was fully backed by U.S. dollars at all times was a lie.” iFinex and its subsidiaries agreed to settle by paying $18.5 million and discontinuing trading with New York residents. It also agreed to produce a quarterly report.

That first report came out in May 2021 and revealed Tether held about 5% of its reserves in anything that people who work in finance would consider cash or cash equivalents (highly liquid non-cash holdings).

The remainder is in a variety of not-really-disclosed vehicles, including 50% in “commercial paper,” another word for short-term loans made to companies, sometimes via intermediaries, which are common to keep cash on hand to cover the difference between the expense of fulfilling sales and collecting the revenue from them. These loans can vary from highly deficient to investments as good as U.S. Treasury bonds. But without the particulars, there’s no way to know whether they’re all junk or not.

Tether’s report came out on May 12, 2021, just after Elon Musk tweeted about cryptocurrency, so it’s not clear to what extent the subsequent crash in value can be attributed to Musk or people’s horror on reading the Tether filing.

For those who may argue Tether isn’t in essence different from a central bank, which uses lots of different assets to back the concept of its currency’s value, I’ll close this out quoting from Bloomberg’s Matt Levine once again. He commented June 16, 2021, on the Federal Reserve expressing concern about the growth in stablecoins:

…the Federal Reserve absolutely does issue its own digital currency, which is called “the U.S. dollar” and which consists of entries on computer ledgers. And consumers absolutely do get the benefits of a stablecoin without the risk of a crypto exchange losing all of their money: They can keep digital U.S. dollars in an online bank account, and pay for goods and services electronically with credit cards or ACH transfers or Venmo, and the dollars in the bank account are always worth a dollar and are insured by the FDIC. Also you can actually use them to pay for goods and services, which is a lot more than you can say for Tether.

The Economics Stop Penciling Out

An upper limit exists in how much a miner will spend to produce cryptocurrency in any consensus mechanism that relies on waste—assuming they’re rational. It would be hard to argue that miners aren’t purely in it for the money, and thus their investment and ongoing outlays of cash to keep things running must generally and over fairly short periods of time produce a positive return. The moment the spreadsheet shows a negative and no path upward is the moment miners start powering down servers, and sometimes engage in fire sales to get rid of equipment that no longer serves their needs.

Proof of work is particularly tricky, because the hash rate is entirely depending on the amount of hardware in operation, the price of electricity for each mining installation, and the current price at exchanges of the cryptocurrency being mined.

Bear with me a moment as I do the math and pretend to be a Bitcoin miner. Say my operating costs include $0.04 a kilowatt-hour for electricity.

On June 9, 2021, about $29 million in exchange-valued Bitcoin was paid to miners as block rewards and fees across 121 blocks. (This is slower than normal, as the computational power of Bitcoin is dropping at the moment.) That’s about $240,000 per block.

Bitcoin consumes an estimated 125 tWh per year, or 342 gWh a day. At my low price of $0.04 per kWh, that’s nearly $14 million in electrical cost. But wait! That’s about the lowest price anyone is paying worldwide, unless they have their own renewable power (and then have to factor in its amortization and operating costs) or they’re stealing power (not uncommon).

In the United States, the cost is more like $0.15 per kWh, although data centers can get cheaper prices by locating closer to power and in other arrangements. But let’s assume the average global price for Bitcoin electricity is a modest $0.07 per kWh. Uh oh: that’s $24 million.

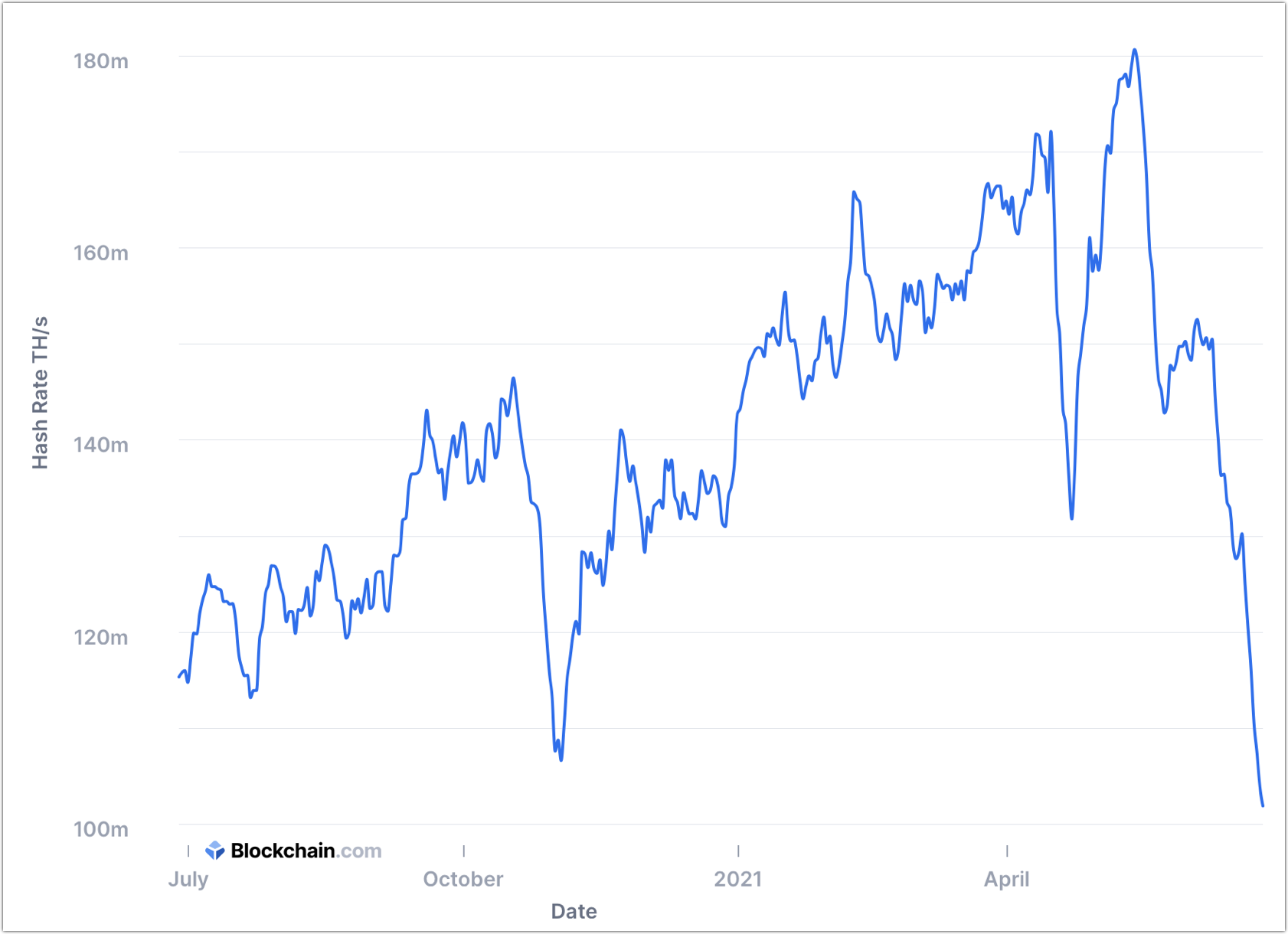

That doesn’t leave much room at all for all the other expenses involved. Miners without cheap power rates are operating at a loss. This explains what you see in this chart showing computational power (the hashing rate) from July 27, 2020, through June 25, 2021 (Figure 11). During that year, one Bitcoin went from $10,000 to $65,000 to $35,000, while hashing went up over 50% and then plummeted with the price.

Miners may be dumping hardware, breaking contracts, and fleeing town, because only a subset of them are making money. The relatively small return also means that miners are likely cashing out in exchanges on a regular basis as the 100-block waiting period passes (under a day) to generate the cash needed to pay for ongoing operations. This need to obtain fiat currency may have some secondary effect in suppressing the price as well.

Of course, there is a possibility of a positive outcome from the current destructive cycle:

First, it establishes a natural limit on electricity consumed, because the volatility churns through miners willing to invest in equipment and facilities and thrashes them when the price drops. Most operation at the scale necessary to mine Bitcoin at least can’t cycle through that kind of volatility over and over again.

Second, it may continue a drive already underway to make cryptocurrencies ultimately carbon neutral and entirely dependent on renewable energy, largely solar and wind. In the short term, this is good news. But I am dubious about this in the long term—see But What About Renewables?—because it doesn’t solve fundamental problems or provide an incentive to reduce consumption.

Third, Ethereum may see even more buy-in on its proof-of-stake migration, which shaves off costs of operation and provides a more stable way to have the same benefits as Bitcoin and proof-of-work cryptocurrencies.

Ransomware

An oddly off-blockchain threat to cryptocurrency comes from ransomware. Ransomware doesn’t have any connection to digital coin except that pseudo-anonymous payment addresses are a convenient way for criminals to collect payments for illegal acts.

Ransomware is pernicious form of malware that may strike someone randomly, delivered in bulk to people through phishing (real-looking emails and websites that direct you to a fraudulent site), a worm, or a Trojan Horse, for a modest return; or it may be targeted at a big business or institution that the attackers believe can pay the big crypto-bucks.

It has emerged as a popular form of malware because it offers low-hanging fruit. Most malware before ransomware required burrowing into exploits that allowed various forms of hijacking. Software might run on a user’s computer or server that scanned a drive and extract personal details, or which copied and sent keystrokes elsewhere. It might be designed to fool someone into entering financial credentials. Or it might let an attacker rifle through email and text messages to find material to blackmail someone with.

Ransomware, by contrast, doesn’t need deep exploits. The malware typically only affects documents that a user has permission to read and write, in part because Apple, Microsoft, and other operating system makers have hardened their system files, making it far more difficult to find flaws that can be used at scale.

When ransomware can successfully execute on a person’s computer or on a server, it rapidly encrypts files with a key known only to the attacker, and then deletes the source file. If the attack is interrupted in progress, the malware is designed to self-destruct.

A message is left behind, typically in the form that a victim can double-click any file to find, that explains what happened, what amount in cryptocurrency needs to be paid to receive the unlock key, how to test unlock one or a few files to prove that the attacker possesses this ability, and how to purchase cryptocurrency.

Ransomware operators often have technical support, sometimes of high quality, and will sometime negotiate down a price. Some intentionally avoid schools and nonprofits, and may disgorge a decryption key if the victim can prove that.

It’s in the best interests of a ransomware attacker to follow through on the promise to unlock files after being paid, because otherwise the word gets around and few people if any pay.

The near-exclusive use of cryptocurrency among ransomware operators, and for other forms of malware-based blackmail or attacks, makes it a prime target for government officials who want an excuse to crack down on cryptocurrency.

The recent ransomware attack against Colonial Pipeline result in attacks receiving 75 Bitcoins, or $4.4 million at the time of payment. But then it got interesting. A few weeks later, the FBI announced it had recovered 67.5 of those Bitcoins (valued at $2.3 million after the crash in cryptocurrency exchange rates) by apparently cracking a wallet containing the private key or keys associated with the ultimate addresses to which the coin was sent. (It passed through a number of intermediate addresses, according to reporting.)

As the financial publication Barron’s wrote on June 8, 2021: “It’s a sign that the Biden administration has ramped up efforts to get ransomware under control, and that new more restrictive rules may be coming to crypto.”

The Washington Post summarized it thusly: “[A]fter a spasm of high-profile attacks that jarred the nation, the U.S. government now has begun framing the issue as a matter of national—and global—security.”

But for a more moderating view, a former U.S. Department of Justice prosecutor who led a task force on pursuing cryptocurrency crimes, Katie Haun, now heads up a $2.2 billion cryptocurrency fund for a venture capital firm. She told the New York Times in June 2020 in response to a question asking whether cryptocurrency effectively caused the emergence of ransomware:

…absolutely not. I prosecuted many of the Justice Department’s largest online money laundering schemes. In fiat systems, 99.9 percent of money laundering claims succeed. Actually, the thing that really stands out about the ransomware attacks—the Colonial Pipeline is a great example of this. It is unprecedented that the Justice Department would be able to recover the proceeds from international criminal activity so quickly. That timeline is usually years, if ever.