Perform Monthly Tasks

Once a month—perhaps on a different day from the one on which you perform your weekly tasks—set aside about a half hour to perform several additional maintenance tasks: emptying your Trash, running Disk Utility, testing your backups, cleaning your screen, cleaning your pointing device, exercising your notebook’s battery, and checking for ebook updates.

Empty Your Trash

I have no doubt that some readers are now concluding I’m out of my mind. Empty my Trash once a month?! What could he be thinking? The thing is, of those people, some of them are thinking that once a month is far too seldom, while others are thinking it’s far too often!

Your Trash, as you probably know, is just another folder (technically, several folders that act like a single folder). As a result, moving files or folders to the Trash doesn’t delete them, just as tossing a crumpled paper in a physical trash can doesn’t automatically turn it into landfill. On your Mac, as in your home, the contents of the Trash continue to take up space until you empty the Trash (using Finder > Empty Trash), freeing up that space for other files.

How often should you do this? It depends on how you think about the Trash.

Let me put my cards on the table: I am a compulsive Trash emptier. I picked up this habit many years ago when I was struggling to make do with a 20 MB hard disk and every kilobyte counted. If I left items in the Trash without emptying it for more than a few hours, I’d run out of space. Today, even though I have a large SSD with plenty of free space, I still haven’t kicked that habit. On the other hand, because I know I’ll be emptying the Trash shortly after putting a file there, I tend to think of moving files to the Trash as a final deletion from which recovery is impossible, so I don’t take that step unless I’m entirely sure I can do without that file.

On the other end of the spectrum are what I’ll call pack rats. They cringe at the idea of getting rid of anything for good. For them, the Trash is just another folder, and, unlike a physical trash can, it never gets full. So they freely move files and folders to the Trash that don’t seem important at the moment—just to get them out of the way—because they can open that folder at any time and get the files back.

In between, of course, are most people. If you’re that hypothetical person in the middle of the Trash emptying spectrum—neither a pack rat nor a compulsive emptier—let’s just say that today is a good day to empty the Trash. For those at the extremes, here are some reasons why you might want to move toward my proposed happy medium of monthly Trash emptying.

For those on the compulsive side, consider this:

Everyone makes mistakes. You can probably recall at least one occasion when you had to fish a file out of the Trash. Remember that once you’ve emptied the Trash, the only way to recover deleted files (other than to retrieve them from a backup) is to try expensive—and often unsuccessful—undelete utilities or to send your drive to a very expensive data recovery service. Giving yourself a safety net might save you grief later.

Modern SSDs and hard drives are large enough that you probably won’t run out of space if you wait a few weeks before emptying the Trash.

You’ll be able to focus on your work and be more productive if you don’t keep looking to see if there’s anything in the Trash.

For those who lean more toward being pack rats, think about this:

How many times have you had to recover a file from the Trash that was more than a month old. Ever? If that’s a common occurrence, you should seriously consider revising your filing habits.

Your Mac’s storage device may be large, but it’s not infinite. You’ll eventually run out of space (see Disk Usage). In the meantime, all those extra files can contribute to increased file fragmentation, potentially decreasing your Mac’s performance (consult Defragment Your Hard Disk). Admittedly, fragmentation is not a problem with SSDs, but you still need to have at least a bit of breathing room for good performance. Emptying the Trash can help.

All those extra files, merely by sitting in the Trash, could result in productivity losses due to longer waits for backups and diagnostic utilities to run.

And for everyone, regardless of how frequently you empty the Trash, here’s one huge piece of advice: look before you leap. Get into the habit of opening the Trash folder (by clicking the Trash icon in your Dock) and scanning its contents before you empty it. It may take a few minutes, but you’ll be far less likely to delete a file by mistake.

Use Disk Utility’s Repair Disk Feature

Earlier (in Run Disk Utility), I suggested using Disk Utility to preemptively check for and eliminate common disk gremlins. Because disk errors do arise during ordinary computer use (seemingly of their own accord), I suggest using Disk Utility’s Repair Disk command once a month. This advice differs from most of the tasks I recommend, in that repairing your disk is typically more of a troubleshooting step than a maintenance step; however, given the frequency of random disk errors and the fact that they often exhibit no symptoms at first (and can lead to much more serious issues if not addressed), I think it’s justifiably considered a preventive measure.

Test Your Backups

No matter what backup software you use—Time Machine, Backblaze, Retrospect, SuperDuper!, you name it—things can and do go wrong. Your backups may run, or appear to run, day after day and week after week without displaying an error message or giving you any reason to doubt that your files are safely backed up. But more than once, I’ve tried to retrieve a file that I thought was backed up, only to find that it wasn’t there! Maybe my backup disk had developed problems, or an online backup provider had its connection go down, or some other random error occurred, but whatever the reason, the file that I needed wasn’t there. I’ve heard similar stories from many people, including Mac experts.

The point is, it’s one thing to install and use backup software, but it’s another thing to be sure it’s working properly.

TidBITS publisher Adam Engst has declared every Friday the 13th International Verify Your Backups Day. He suggests that every time Friday the 13th rolls around, you should check to make sure you can restore files from your backup. That’s an outstanding idea, but I’ll go one better and suggest you do it every month.

Specifically, I recommend that you do the following things:

For versioned backups (and online backups, if you use them), try to restore a few random files or folders from different locations on your disk. Check the restored files to verify that they’re intact and have the right data in them. (You can delete the restored files from your Mac’s drive—but not from the backup!—once you’ve verified them.)

For bootable duplicates, hook up the drive with your duplicate, restart while holding down the Option key, and select that backup drive as the startup volume. If your Mac starts up correctly (and without displaying any error messages), you’re probably in good shape—but confirm that you have indeed booted from the backup by checking the startup volume name in Apple > About This Mac. Then go ahead and restart from your internal drive as usual.

This quick check need not be exhaustive, because if you can start from your duplicate and a few random files from your archive look OK, chances are everything else is OK too. But if your check shows problems, you’ll want to resolve them before disaster strikes!

Consider Clearing Certain Caches

As you use various apps, they often store frequently used information in files called caches. For example, when you visit a website in Safari, it stores the text and images from that site in a cache, so that the next time you go to the site it can display the pages more quickly (because it needn’t download them again). Another example is Microsoft Word, which can display the fonts in the Font menu in their own typefaces. If Word had to read in all those fonts each time you used it in order to build the Font menu, every launch could take a minute or more, so Word builds a cache that contains all the data it needs to draw the font names.

Caches are good—usually. But sometimes they cause more problems than they solve. One problem occurs when an app has cached hundreds or thousands of files—so many that reading the caches takes longer than reading (or recomputing) the data they contain. A more serious problem involves damaged cache files. Maybe an app failed to write the file correctly in the first place, or the data in the cache was bad, or a disk error corrupted the cache after the fact. Whatever the reason, a corrupted cache file can cause an app to crash, run slowly, or exhibit any number of incorrect behaviors.

Several utilities provide a one-click method for deleting one or all of your caches; I list some examples ahead. But whether you use a utility or manually drag files to the Trash, I recommend against blindly deleting all your caches; as I said, they usually help rather than hinder. However, a few caches in particular have notorious reputations, and clearing them periodically tends to make the apps that use them run more smoothly. My recommendation for weekly cache maintenance is to delete just a few types of cached files, as I describe next. (Clearing other caches is more of a troubleshooting step than a preventive maintenance step.)

Safari Main, Favicon, and Preview Caches

Safari stores quite a bit of information for later use, including your browsing and search history, cookies, usernames and passwords, autofill information, Top Sites, and a list of downloaded files. However, only the following function as true caches—that is, Safari tries to load each of these if it’s present, or (re)builds it automatically if not:

The main cache: Although “main” sounds all-encompassing, it refers only to the contents of webpages (including graphics). This cache is stored at

~/Library/Caches/com.apple.Safariin theCache.dbfile and thefsCachedDatafolder.The website icons database: This refers to stored favicons, those tiny icons that appear next to a site’s URL in the address bar, which reside in a database separate from page contents. The favicon cache is stored in

~/Library/Safari/Favicon Cache. In addition, larger, mobile-optimized icons may be stored in~/Library/Safari/Touch Icons Cache.Local storage: When you visit a site that stores data locally (beyond cookies), the usual locations for that data are

~/Library/Safari/Databasesand~/Library/Safari/LocalStorage.

Because even under ordinary use these cache files have a tendency to bog down Safari (not to mention chew up disk space), it’s useful to clear them periodically.

Safari once had a menu command to clear only the main Safari cache, but it’s now hidden. To see it, first go to Safari > Preferences > Advanced and select “Show Develop menu in menu bar.” Then choose Develop > Empty Caches (⌘-Option-E).

To clear the other two types of cache, you can quit Safari, drag the items listed above to the Trash, choose Finder > Empty Trash, and then reopen Safari. There’s an easier way, but it also deletes your cookies as well as your browsing, search, and download history—which may not be what you want (see Delete Your Cookies for more information).

Only if you’re certain you want to delete the whole kit and caboodle:

Choose Safari > Clear History. A dialog appears (Figure 12).

Figure 12: You can clear several categories of Safari’s stored information in this dialog. Choose a time period—the last hour, today, today and yesterday, or all history—from the Clear pop-up menu.

Click Clear History.

System Font Cache

macOS maintains a system-level font cache that many apps use. Bad font cache files have been implicated in numerous problems. To delete most of your font caches manually, open Terminal (in /Applications/Utilities) and type this, followed by Return:

atsutil databases -remove

Then restart your Mac and empty your Trash. However, be aware that after you perform this procedure, any fonts you’ve disabled in Font Book will be re-enabled.

If you’re running Sierra or earlier, another way to wipe out these caches is to use Smasher for Mac, a utility that can clear the font caches for macOS as well as for apps from Microsoft Office (discussed just ahead), Adobe apps, and QuarkXPress. (Other utilities that can clear font caches, but with less sophistication and control than Smasher, are mentioned ahead in Cache Clearing Utilities.)

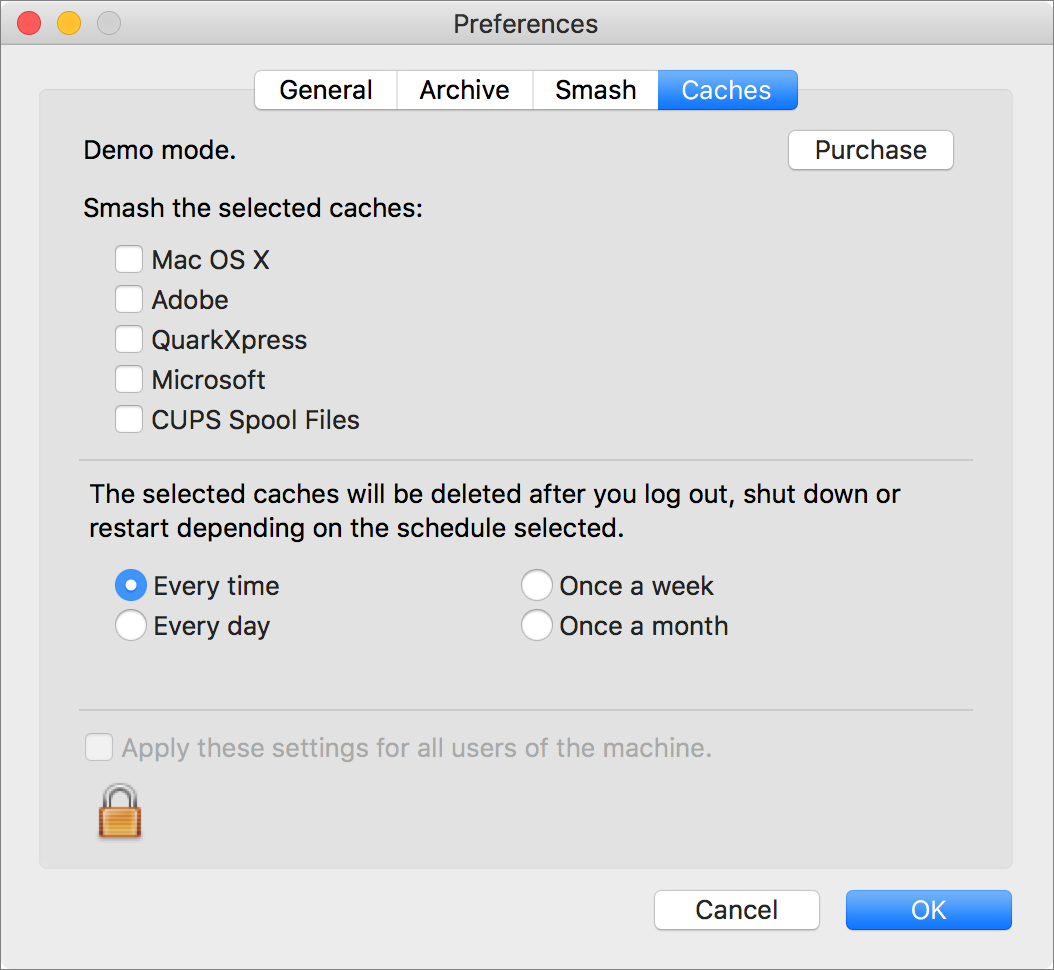

To use Smasher to clear your font caches, first go to Smasher > Preferences > Caches (Figure 13), select which caches you want to delete, and click OK. Then choose Tools > Clear Caches.

Microsoft Office Font Cache

Microsoft Office’s font cache has historically been more prone to problems than the system-wide font cache. To clear it, quit all your Office apps and then navigate to ~/Library/Preferences/Microsoft and drag the appropriate file to the Trash:

For Office 2004:

Office Font Cache (11)For Office 2008:

Office 2008/Office Font Cache (12)For Office 2011:

Office 2011/Office Font Cache

Clean Your Screen

Your computer’s display attracts dust, and over time that can impair the screen’s readability. Also, if your Mac or display has a built-in camera, a dirty display means a dirty camera lens. (It’s also, let’s face it, just yucky.) Once a month, or whenever you can see a thin layer of dust on a black screen, give it a quick cleaning.

To clean a screen, use a soft, lint-free cloth—not a paper towel—moistened slightly with water to prevent static buildup. (You can also use cleaning solutions designed expressly for computer displays, but avoid anything containing alcohol or ammonia.) Wipe the screen gently; LCD displays, especially, can be damaged by excessive force.

Clean Your Pointing Device

Most modern Macs come with either a trackpad (built-in or external) or an Apple Magic Mouse as a pointing device. Trackpads require no maintenance other than perhaps a quick wipe with a moist cloth. Mice, however (and trackballs, available from third parties), are another story.

I spent five years working for Kensington, a company that made its reputation in the Mac world by selling fantastic mice and trackballs. During the time I was there, we saw the computing world move from optomechanical devices (in which a ball turns rollers connected to slotted wheels whose speed and direction are measured with photosensors) to optical devices (in which a tiny camera tracks changes in the texture of your desk’s surface or the trackball’s surface).

The biggest and most exciting advantage of optical designs was supposed to be that they never had to be cleaned. Gone were the days of disassembling a mouse, losing the ball as it rolls across your office floor, and fumbling with cotton swabs to clean dirt and hair off of tiny rollers—a procedure you might have to repeat every few weeks or so. Optical mice have no moving parts—no rollers, no ball—so cleaning should never be necessary.

Experience, however, has shown that although optical devices require less cleaning, they still require some. Specifically, optical mice tend to accumulate dust inside the opening at the bottom through which the sensor watches your desktop. If it becomes clogged, your pointer may move erratically, or not at all.

Optical trackballs have a similar opening above the lens (remove the trackball from the casing to see it) with a similar tendency to attract dust. In addition, the tiny bearings or rollers on which the ball rests can collect dust and hair, preventing the ball from moving smoothly.

And, of course, plenty of Mac users still have older pointing devices that use the ball-and-roller mechanisms and therefore require what we now think of as old-fashioned cleaning.

Your input device most likely came with cleaning instructions, so I’ll simply say: follow them now. If you don’t have the instructions (and can’t find them on the manufacturer’s website), they generally boil down to removing visible dust and gunk from wheels, rollers, bearings, and other moving parts (and away from the openings used by optical sensors). A slightly moistened cotton swab will work nicely.

For most people, once a month is a reasonable cleaning interval. If you have pets, you may need to clean your mouse or trackball more frequently; if you work in an Intel clean room, maybe never!

Exercise Your Notebook’s Battery

Early portable computers used NiCad batteries, which were subject to the dreaded “memory” effect. To get maximum run time from them, you had to discharge them completely before recharging them; if you failed to do this, even a fully charged battery might run out of power after a short time.

The lithium-ion polymer batteries used in modern Apple devices don’t suffer from the memory effect, and in most cases require no special maintenance. However, Apple formerly advised owners of Mac laptops to avoid leaving them plugged in all the time. For users who rarely unplug their laptop, Apple’s advice was to completely discharge, and then recharge, the battery at least once a month. Although Apple no longer recommends this, what I know about battery technology suggests that it’s still a pretty good idea. (Granted, this takes longer than the half hour I suggested you allot for your monthly tasks, but you can discharge your battery while using your Mac for other things.)

Check for Ebook Updates

All right, this isn’t exactly Mac maintenance, but it’s a good idea anyway. Make sure you have the latest versions of all your ebooks—especially your Take Control books!

Ebooks, like software, can be updated at any time. Unlike apps, however, ebooks generally don’t have mechanisms that automatically inform you of available updates and download them for you. In most cases, you’ll have to do this yourself. Here’s how to check for updates for a variety of ebook sources:

Take Control: For individual Take Control ebooks, click Ebook Extras on the cover of the PDF version, or click the “access extras related to this ebook” link in the Ebook Extras topic near the end of the book. Or, to see all your purchased books and download the latest versions of any of them, log in to your Take Control account. For further details, including information about subscribing to ebook update lists, see our FAQ.

Books (or iBooks): Click the download

button in the upper-right corner of the Books (or iBooks) window to display a list of any available updates. Then click Update to update a single title or Update All to download all updates. (This applies to books purchased from Apple only, not to PDFs or manually added EPUBs.)

button in the upper-right corner of the Books (or iBooks) window to display a list of any available updates. Then click Update to update a single title or Update All to download all updates. (This applies to books purchased from Apple only, not to PDFs or manually added EPUBs.)Amazon Kindle: For major updates only, Amazon generally sends all purchasers email messages with instructions. For minor updates, go to the Manage Your Content and Devices page and sign in to see a list of all your purchased titles. An Update Available link will appear next to any title with an update; click this link and follow the instructions. Or, to turn automatic updates on, follow the directions in Turn Automatic Book Updates On or Off.