The role of disciplinary thinking in research processes

Abstract:

A paradigm shift is needed to make the teaching of research processes what it needs to be. Central to such a shift will be an invitation to students to enter into our disciplines. Each discipline, as a combination of philosophy (epistemology), method and application, embodies one or more metanarratives, that is, explanations of why we do what we do. While experts understand their metanarratives well, students do not. In fact, lack of subject and research process expertise may well be a significant reason why students stay outside our disciplines, learning about but not actually participating in them. Students require a consistent model for the research processes they are learning (we suggest the scientific model). More than that, they require that their professors find a radically new way to invite them into the disciplines they are studying.

We have come to an impasse. Information literacy is, indeed, the largest blind spot in higher education today, but the chances of ever making it what it needs to be seem remote. We must consider a paradigm shift that goes beyond merely opening the curriculum to some library instruction sessions, or having a librarian help develop some research exercises. The gap in research processes ability is an endemic issue, infecting everything we do in education. Why? Because information handling is at the foundation of any form of study you can imagine.

The barriers to developing skilled student researchers seem almost insurmountable – lack of understanding of the problem within academia, lack of space in the curriculum, lack of administrative support for information literacy initiatives, lack of desire among many faculty to make significant changes to tried and true patterns of education, and a pervasive argument that teaching research processes is someone else’s task, if they can be taught at all.

That is why the bulk of all information literacy instruction today is done by librarians within short sessions, generally one hour or less. In many institutions, this amounts to nothing more than a single session throughout a student’s entire undergraduate program. Considering the glaring need for information-literate graduates, it seems inconceivable that the teaching of research processes is so marginalized, but that is what we have. For every rare extensive program, there are dozens of institutions that have paid only lip service to the problem.

Webber and Johnston, commenting on short-term information literacy, wrote:

The result may be a learning and teaching strategy which fails to engage the student at anything but the most superficial level. The student may gain a few tactics which enable him or her to negotiate some specific information sources. However, the student does not become information literate, capable of engaging in a fast-changing information society. (2000, p. 385)

The result for the marketplace is that workers, who depend on information for much of what they do, have a poor understanding of the nature of the information they are working with, waste huge amounts of time acquiring it (if they find it at all), and use it in inappropriate ways that put the enterprises they work for at risk (Kirton and Barham, 2005). When we consider all that information literacy entails, a much more comprehensive solution is required.

The development of scholarly ability within a discipline – content and process

Information literacy, the ability to handle information with skill and understanding within research processes, is not a matter for remedial instruction. The task of teaching research processes is akin to learning a new language. It requires long-term development that is progressive and constant over a significant period of time. We will argue shortly that students will only become information literate when information literacy becomes part of the foundation of their education.

How that is best accomplished has a great deal to do with having students begin to do higher educational disciplines, rather than acquiring just what constitutes a discipline’s knowledge base. Essentially, educators are going to need to move from teaching about their disciplines to enabling their students to become disciplinarians. The expression, “Welcome to my world,” encapsulates the goal. We need to educate, not merely to inform. We must invite students into our world and there reproduce ourselves in them, turning our students into active practitioners in our disciplines.

At the heart of such an endeavor is the task of understanding for ourselves how our disciplines work, how they have formed themselves, not just as bodies of knowledge but as entities akin to living beings with both content and processes that allow them to “live.” Fear not, however. This is not as esoteric as it may appear.

What do we mean when we use the term “discipline?” In most regards the whole idea of a discipline is an artificial construction. Disciplines arose out of necessity: Historically, as knowledge expanded with the rise of the printing press, it became impossible for any one scholar to have expertise in everything. Thus academia began defining areas of knowledge that had discrete boundaries and a critical mass of published research and researchers built around them. It was not that each discipline lived in its own isolated universe bearing no relationship to any other discipline, but that, internally, there was enough going on within the discipline that it gained its own recognition and ongoing viability within the broader academic enterprise.

Essentially, then, what makes a discipline a discipline is a sufficient number of publications and practitioners within strict bounds of subject matter, as well as a perceived legitimacy of the discipline by academics in general. This latter element is crucial. Merely producing a lot of research or academic discourse within an area of study does not legitimate a discipline, as is clear from ongoing controversies over such proposed disciplines as parapsychology. Rather, the legitimacy of any discipline is determined by its recognition within the academic community.

Essential to a discipline are three factors: Philosophy, method, and application. Let us consider each in turn with regard to the way in which it addresses the information and research processes it encompasses.

Philosophy: epistemology of information

“Epistemology” is a philosophical concept that considers the nature of the sources of information we value. It asks questions like these: Where does our disciplinary information come from? What forms does it take? Why is such information seen as significant to our discipline? How do we determine what sources are reliable/valuable and what are not? For those of us who have functioned for some time within a particular discipline, our epistemology is second nature. Not only do we not think much about why we value some forms of information over others, but we might be hard-pressed to teach our epistemology to others. Still, knowing where our information comes from and what significance it has for the work we do is vital to the foundation of disciplinary work. It is also a realm neither understood nor properly appreciated by our students. If their ability with research processes is going to grow, they are going to have to understand the nature of the information field within which they are working.

Helping us are all those “philosophy of” or “theory of” introductory courses that students dread and many faculty members dislike teaching. Why do we teach them? Often because they are seen as essential to knowing a subject area, though it is not at all clear what is essential about them. If we were to think in terms of epistemology, however – how we know what we know, what are our information sources, and why we value some more than others – we might be able to justify the importance of “philosophy of” courses that teach just those elements.

For now, let’s delve a bit deeper into epistemology. A sudden descent like this into philosophical thinking may seem challenging to the attention span, but it is important.

There was a time in which the concept of “information” could be summed up as “that which gives us the foundation for discovering truth.” Postmodernism and Poststructuralism have challenged the assumption that the sources of our information are objective and values-neutral enough to make the acquiring and use of information a sure path to truth. Kapitzke (2003), for example, has argued that information can no longer be seen as operating in some sort of vacuum, separated from the social and historical processes that shape it and justify its existence. Information is not neutral, nor is it apolitical.

Kapitzke goes on to call for us to recognize a hyperliteracy (a literacy that recognizes the various forms and media in which information is found) as a better explanation of the many environmental factors operating when information is created and used. Hyperliteracy includes “intermediality,” the idea that we must view the information process within the worlds of both its producer and user. The one who created the information may not live within the conceptual environment of the one who uses the information, creating a situation in which there is a disconnection between the intent of the creator and the interpretation of the user. Recognizing this reality will help us maintain a constant analysis of the cultures and assumptions of both creator and user.

This idea, that information always is contextual and exists in tension between producers and users, is helpful, yet it neglects one aspect of epistemology – the reality that a source of information needs to be evaluated by criteria that are more or less universally acceptable. We may contextualize the information process, but we must agree upon the interpretive means we employ to recognize what the writer writes, how the information became published, and how the reader reads it. Also, a proper epistemology looks at the qualifications, presuppositions and biases of the writer as well as of the reader.

Here our students need to learn how to use commonly accepted criteria that help them judge the extent to which they can believe, rely upon, or use the information according to the purpose it for which it was created. Unless our epistemology makes a god of subjectivity, any philosophy of knowledge has to ask questions like, “Who wrote this? Does she have the required knowledge base to make her writing reliable? What presuppositions have set the direction for her approach to this topic? What biases do I bring to my reading of her work? What value will this piece of information ultimately have to my quest?”

Academic information generally lives within the context of a subject discipline. In a subject discipline, discourse is carried out by specific though often unwritten rules that make any particular piece of evidence or product of research either valid or invalid, based on the criteria established by the discipline. We might well accept the famous warning of Martin (1998) regarding political bias within disciplines, but Keresztesi (1982) has made it clear in his pioneering article, “The Science of Bibliography,” that the recognition of an area of study as a discipline within the university is the only way for it to achieve widespread approval in society.

This tells us that, though bias may exist within the creator, the publisher, and the reader, we still need ground rules that will guide us in our recognition of the value of information sources and in the means we use to understand them. Epistemological issues are not insignificant ones. Students who understand the forces at work in the production and validation of information sources in their disciplines are prepared to use information intelligently, effectively and ethically to address the research needs which they are facing.

The methodology of the information quest: finding a research model

The teaching of research processes in disciplines, when it is done at all, is seldom built around a coherent research methodology. Part of the problem has been the fact that much of what we have done in the past to attempt the teaching of research processes has really been bibliographic instruction that focuses on the library and its search tools, thus missing the concept that research involves larger processes. Even when we have a clear epistemology in place, the idea of a guiding methodology that shows students how to move from points A to B to C is often lost in the rush to move our instruction from philosophy to application. Thus, while we may teach about the sources of our information, we skip research method in favor of showing students how to use search tools. This creates a library-based architectural model of instruction – here is the catalog, these are the databases, and here is how you use them. Students are left with a box of tools but no blueprint for the project.

We require some way to guide students from the beginning to the end in their research, encompassing all aspects of it. This works best if we employ and teach a research model that enables students to have a clear mental picture of the research task. Commonly, students spin their wheels at the beginning of any piece of research, trying to understand the topic they are working on and struggling to find a direction to take both in finding the information needed and in determining what to do with it in order to produce a coherent product (Head and Eisenberg, 2010). They rarely have a concept of the process involved in moving from start to end. This is what a research model could provide. It would, in essence, explain both the nature of research and the steps required to pursue it.

Research models, however, are open to criticism. The widely used information processing paradigm (McGuire, 1972) that sees a progression from data to information to knowledge has been criticized by many as being too structured and not open enough to the possibility that information can just as easily lead to confusion. Marcum (2002), in particular, has pointed out that knowledge is not organized information but a quantum leap from information to cognition, understanding and experience. He argues: “Knowledge is not certainty but is a set of beliefs about causal relationships between phenomena” (ibid., p. 12).

Marcum further points out that the information processing model, as well as most information literacy models, fails to take into account the crucial role of the researcher in formulating knowledge. “Too little acknowledgment is afforded to the context brought to the process by the learner” (ibid., p. 12).

We might, therefore, give up on the idea that we can find a methodological framework, or research model, to guide the teaching of research processes. Knowledge-building is, to be sure, an eclectic and multi-party process involving acquiring data and making sense of it, while considering both its biases and ours. So it may well be that defining a single research method is at best artificial and at worst impossible. But the alternative is simply to explain to our students how information works within the discipline and then turn them loose on the tools without giving them any process to follow in moving through their research.

Clearly, many students struggle in the early stages of research projects, not seeing a path ahead and feeling a great deal of anxiety that is not alleviated simply by providing them with a rubber-stamp method (Kuhlthau, 2011). It is a fact, as well, that actual research processes are often cyclical, so that initial information gathered leads to reformulation of the research question/hypothesis, leading to more information gathering and writing, which may cause the researcher to return to the resource acquisition stage to bolster the knowledge base or even back to the hypothesis once again to clarify it. This is particularly true of research scholars, whose methodologies are varied and often appear to have no organized structure (Stoan, 1984). But we do not have sufficient reason to avoid putting the application of whatever research processes we are teaching within a methodological framework. As Bodi (2002) has pointed out, established scholars have a knowledge base that allows for the ambiguities and potential confusion of circular research. University students, having a much less mature knowledge base and, indeed, lacking a coherent sense of the purposes and techniques of the research process, flounder in their research, often rejecting whatever method they have been taught but substituting nothing better. They need a fairly consistent road map.

Librarians tend to teach a step-by-step, linear search strategy, but research, especially in an electronic environment, is interactive and circular. A coherent, flexible research model that can be adapted to various instructional sessions is necessary, but we need to be clear that one strategy does not fit all circumstances. (2002, p. 113)

Without some sort of flexibly conceived framework for research method, any mechanical skills remain orphans, lacking a blueprint to determine when they should be used. The best way to instill a research methodology is to build assignments around a research process, providing examples that indicate when, and in what manner, the researcher will need to deviate from the normal pattern. In this way, students do not just have a set of tools and some skills to use them, but they also have a process by which using the tools can lead to understanding and problem-solving.

There is a time-honored methodology available to us, however, which can answer most of the methodological doubts we have raised to this point. It is the scientific method. Instantly, we can raise a number of objections – the scientific method too is artificial, limits creativity, and is too rationalistic to deal with all the subjectivity involved in turning information into knowledge. But, as a method, it brings together the main features of most problem-solving in the human enterprise – development of a working knowledge of the issue, creation of a statement that crystallizes the nature of problem at hand (hypothesis or research question), a review of what is currently known about the issue (including a delineation of the various points of view that are held), an exercise to compile and/or evaluate evidence, and a conclusion that weighs all that has been discovered and finds a solution. This method can take many views on an issue into account, can properly address the bias brought by the researcher, and can help discern what passes for “information” to determine its quality/usefulness/reliability in helping to deal with the stated problem.

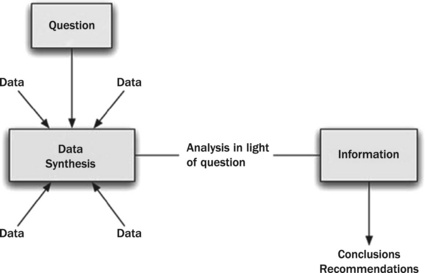

The scientific research model can be pictured simply as shown in Figure 5.1. Figure 5.1 includes the formulation of a question (or hypothesis), data gathering and synthesis, some sort of process of analysis (evaluation), consideration of resulting information, and development of conclusions. As such, it can work in everything from a science project with literature review to a history paper on the role of 9/11 in shaping immigration policy in the early twenty-first century.

Though the actual course of a research project may not be nearly as linear as Figure 5.1 appears to make it (Kulthau, 2011), it at least puts forward an A–Z process to conceptualize and carry out research in a variety of disciplines. For students lacking any real concept of what they are doing or where they are going in research, it can provide a basic roadmap.

Instruction in application skills

Teaching the application of a research process – how to use keywords and controlled vocabularies; how to search catalogs, databases, and the Internet; how to evaluate information sources – is the predominant territory for many information literacy instructors today. Generally, application is not taught to any great extent by subject faculty members, who leave it for librarians (Bury, 2011). Application skill is important, but as we have argued, it needs to be taught within the spheres of philosophy of information (epistemology) and use a flexible research method if students are to bear fruit in the effective acquiring and use of information.

To use an analogy, the application of research is like a tradesperson’s skill with his or her tools. Proper use of the tools is not enough if the tradesperson has not been educated in the engineering and regulatory aspects of the trade and has not developed expertise in using the right tool to accomplish each stage of the task with skill.

If literacy is the ability to read, interpret, and produce texts valued in a community, then academic information literacy is the ability to read, interpret, and produce information valued in academia – a skill that must be developed by all students during their college education . . . Students must learn how information functions in proof or argument, and why that information is accepted while other information is not. Ultimately, students need to produce information that meets the community’s standards . . . Information literacy, seen in this way, is more than a set of acquired skills. It involves the comprehension of an entire system of thought and the ways that information flows in that system. Ultimately, it also involves the capacity to critically evaluate the system itself. (2006, p. 196)

This requires more than remedial library instruction. It must encompass a comprehensive program of student development. Now is the time to get the teaching of research processes firmly on the academic map, with a level of credibility that will be unassailable. There is certainly enough literature available to prepare us for the teaching task and there are sufficient teachers, if they are equipped, supported and motivated. If there are inadequacies in any aspect, they can be overcome. But we absolutely must take teaching research processes as seriously as do any other foundational aspect of higher education.

To make research processes instruction work, it has to find a home within the curriculum, not as an elective, nor as one program among many, but as an element of the core of every student’s education. As such, it will take a variety of forms and venues from stand-alone courses in majors to through-the-curriculum credit-bearing modules within existing courses. But to make it anything less than a core goal is to leave our students unprepared for the information age.

Metanarrative as a way of conceptualizing research processes

There is one idea that pulls together philosophy, methodology and application within the disciplines: the concept of metanarrative. The term “metanarrative” is unfamiliar to some and highly controversial to others, thus calling for another brief foray into philosophy.

It is a truism that practice arises out of philosophy and that practice divorced from philosophy is often half-blown and less than helpful. This is certainly the case in the realm of research processes instruction, where a tendency to move to the pragmatic before we know why and what we are doing often fragments our endeavors into a wide variety of disparate initiatives, few of which accomplish any more than a small part of the task. The philosophical concept of “metanarrative” can bring cohesion to our efforts to create a rigorous plan for teaching research processes within disciplines.

The term “metanarrative” itself is not particularly mysterious. Our daily lives are filled with a series of “narratives” – how we got to work this morning, how we handled a particular situation, how we decided what to have for lunch, and so on. Binding our smaller narratives together is one or more metanarratives, that is, larger explanations of our reality that guide us through our smaller narratives. Metanarrative explains in big picture fashion why we do what we do and thus defines our view of the world or a portion of it.

To consider an example, those who teach research processes believe that enabling students to handle information skillfully is an essential element of their education and must be pursued vigorously. That is an example of a metanarrative. It is a guiding belief or consensus that helps us set our educational goals and provides the rationale for doing what we do. Thus, a metanarrative is both a motivator and a way of measuring the “truth” or validity of what we are doing. Capitalism is a metanarrative for business and economics, as is, alternatively, socialism. Scientific method is the metanarrative for experimentation in the sciences. Religions are metanarratives for individual lives of faith.

With the rise of Postmodernism, the concept of a metanarrative, as an embracing explanation or rationale for why we do what we do, has come under attack. French philosopher Jean-François Lyotard (1984), and Michael Peters (1995) from the field of education, among many others, have argued that the idea of a metanarrative cannot stand as a philosophical or even a practical concept because there are too many diverse metanarratives to allow for consensus on much of anything. To say that a discipline uses a certain method to discuss issues and advance knowledge is to fly against the reality that there are multiple methods in every discipline. What is more, they argue, there is no consensus about how any academic enterprise is to be furthered, and if there were such a consensus, there would be no way of determining whether it was more “true” than some other possible consensus.

If, indeed, metanarrative is a useless concept, then we have little to talk about. But Postmodernism, focusing on subjectivity and rejection of the rationalistic idea of truth, has in recent years increasingly been losing its own credibility. In many ways it has always been a philosophical concept rather than a practical reality, a Western luxury embraced by we who have most of our daily needs met and can afford to speculate on our diversity rather than clinging to our commonality. While Postmodernism has well taught us that we are all essentially subjective beings whose personal experiences color all that we see and do, it has failed to recognize that in the real world we must live by consensus to survive.

While it is easy to make the case that each of us is subjective, so that coming to a consensus/metanarrative about why and how we do things is rarely possible and is probably invalid if we do so, the fact is that we all, in the practical world, live by consensus. Traffic in our streets flows well (with some exceptions) because we agree on what the rules are, even when there are no police officers nearby. Written communication is possible because we agree on the symbolic meaning of letters, definitions of words, and grammatical structures of sentences. Thus in the face of Postmodern criticism, we can continue to affirm the reality of metanarratives that guide the way in which we function, do our disciplines, and so on.

Let’s bring this down to the task of teaching research processes. We are arguing that we must move away from our often fragmented approaches and enlist the aid of metanarratives based on the way scholars in disciplines actually think about and perform research to further knowledge.

Disciplines in the academic world each carry something of a consensus about the way to “do” that discipline. In fact, disciplines themselves are defined as much by their beliefs, values and agreed-upon methods as they are by their subject matter. While disagreements arise (some of them heated), discipline practitioners tend to work out their problems and maintain their consensus about the best ways to do their work, or else they form separate schools of thought, each with its own consensus. But the affirmation continues that there is a consensus about why and how to do things, or a “metanarrative” of the discipline. It is obvious that there is no single metanarrative in any discipline. Different scholars approach their work in different ways. Some are conservative, while others are radical, constantly pushing the boundaries. But this in no way negates the fact that disciplines have overarching conventions, consistent ways in which they live and advance, based upon what they commonly value and believe.

All of this serves to make a crucial point – the teaching of research processes works best when it is structured within the idea of a metanarrative. Even when we move in “interdisciplinary” directions, there are metanarratives that define what we are trying to accomplish and identify methods that will succeed better than will others.

Learning about versus doing

There is a tendency in higher education, models of which date back to the time of the Renaissance, to see the educational task as passing the knowledge of the expert down to the novice. Thus we continue to promote the lecture, which some wag long ago described as the transmission of information from the professor’s notes to the student’s notes without passing through the mind of either.

The lecture, as the primary mode of education, has come under attack in recent decades for perpetuating a false notion of what it means to be educated. Those who teach at university level are likely well aware of the arguments against it: students retain more by “active learning,” while the lecture is essentially a “passive” exercise; the lecture exacerbates the idea of a large distinction between expert and novice, as if only experts really know things; students these days demand engagement, which they don’t find in a lecture, and so on. Likely, the lecture itself will never die as one means among many to educate, but it has certainly been challenged.

What is not often stated, however, is that the lecture, when used exclusively, creates a distance between the learner and the subject matter. The exclusively lecturing professor is saying something like this to the student: “This subject matter is my territory. I will pass some of my knowledge onto you, but please do not dare to believe that what you hear makes you an expert. My task is to teach you about my subject matter, not to enable you to do what I can do with it. I am the expert and only I can truly do this discipline. You are not part of my academic social circle, which cost me so much time and energy to enter and inhabit.”

On at least two levels, such a message accords with the realities of academic life. First, the very essence of expertise appears to be its distinction from lack of expertise. We value our experts precisely because they are not like us. If they were like us, they wouldn’t be experts, would they? Academia, in fact, has a strongly vested interest in perpetuating expertise as the primary reason for its being. A professor is a professor because he/she knows and does things that set them apart to be able to teach others.

The tendency, therefore, in many institutions of higher learning is to teach students about the disciplines, assuming that they will remain outsiders until they have paid the same dues their professors have done, in the trenches of comprehensive exams and dissertations. Like a walled community of elites, we guard our expertise, not imparting any more of it than we have to, for fear that the masses may end up wandering our streets and spoiling our exclusivity. This may seem extreme, but it spells out at least one reason why students tend to learn about disciplines rather than learning to enter into and actually to do disciplines, at least until they reach Master’s and doctoral programs.

A second reason rests in the reality that students lack the knowledge to be genuine disciplinarians like us. Would we really want an undergraduate, or even a beginning graduate, student to be messing around in primary sources or doing actual original experiments? When it does happen, we are generally fairly paternalistic about the outcome, seeing it as a mimicking of genuine research rather than research itself. How can students be expected actually to do a discipline when they are outsiders trying to get in but lacking the qualifications to do so?

Thus our carefully guarded expertise and our limited opinion of student abilities tend to keep students on the outside of our disciplines, where they learn about the subject matter and imitate some of the method but never actually enter into the heart of what it means to be an actual disciplinarian. Perhaps there will always be some such barriers, but, if we are seeking skilled student researchers, we need to get past these limitations, to stop protecting our turf so strongly, and to believe that genuine research rather than pale imitation is both possible from students, and necessary.

The difference between disciplinary experts and undergraduates

It is a long process from the first undergraduate year at university to completion of a Ph.D. and entrance into a teaching and research post of one’s own. One can scarcely recall any longer what it was like to be that entering undergraduate walking with trepidation into Dr. Smith’s philosophy course for the first time. One can hardly remember that first chemistry laboratory assignment, when nothing worked the way the manual said it should, and the fear of humiliation was a constant companion.

But that’s just the point. We scarcely recall what was like to be an undergraduate. Probably it was frightening, but we were bright and motivated young people who coped and learned and eventually triumphed over whatever adversity was besetting us. True, we were probably more intelligent than many of our class members, but, frankly, a lot of them seemed unmotivated and confused. They lacked our skills and our drive. Now these former fellow students are merely part of our dim past because few, if any, of them actually went on to doctoral studies like we did.

We have become experts, defined by our degrees and publications, as well as, hopefully, our track record for imparting our knowledge to appreciative students. We believe we are doing a good job of teaching, though student research projects seem shabby in contrast to the sorts of things we produced when we were undergraduates (hindsight tending to cast a golden hue over everything). Students, in fact, seem somewhat baffled by our directions to them regarding these projects, no matter how carefully we formulate our wording. What is so difficult, for goodness sake, about developing one of seven possible topics, finding a mere eight to ten references from scholarly sources (at least three of these being journal articles), and writing a project, using a good dose of critical thinking? Any one of us could produce a 3,000-word paper of this type in a few days, with all of our references cited in flawless style.

What, then, is going through the head of the typical undergraduate or even the head of someone in the first year of graduate study? You might be surprised. I am reminded of the famous Far Side cartoon where the dog Ginger’s master is berating her about something. He thinks he is being perfectly clear, but all she hears is “Blah, blah, blah, Ginger, blah, Ginger, blah, blah, Ginger.” The difference between a disciplinary expert and an undergraduate is more than a distinction in level of knowledge. The two are actually living in different worlds using different languages.

Librarians are in a unique position to observe the communication problem, and those of us who are academic reference librarians encounter it constantly:

| Student: | Professor Smith wants 3,000 words on 1930s Marxism at Cambridge University. |

| Librarian: | Do you have some sense of how you are supposed to address the topic? |

| Student: | With at least five books and three journal articles. |

| Librarian: | What have you done so far? |

| Student: | Wikipedia article on Cambridge U. It didn’t have anything I can use and Dr. Smith hates Wikipedia anyway. |

| Librarian: | What course does Dr. Smith teach? |

| Student: | European politics. |

| Librarian: | Did he tell you what the goal of the project was? What does he expect you to accomplish? |

| Student: | To write about Marxists at the University of Cambridge. Explain about them. |

And so on. The student clearly thinks the goal is to find out what she or he can about these Marxists and then write it out. The professor, who is calling for critical thinking, is seeking some sort of analysis of the role of these Marxists, or of their importance within European political movements of the era, or whatever. It seems so obvious that this is a rich topic for cutting-edge critical thinking (perhaps even an analysis of the fascinating influence of former Cambridge student Kim Philby in contributing to the politics of the Cold War). Yet the student seems primed to regurgitate sources, re-describe what is already known, and show little to no use of critical thinking processes. There is no sense that there actually is a goal to the project other than explaining the facts.

What went wrong? This student, while she or he can study up on the topic, has little sense of how such a topic is to be addressed. She or he has no grasp of the purposes of political historical research, let alone understanding which research resources are best and most suited to addressing those purposes. She or he is an outsider in a field Dr Smith thinks of as his own. This student is not part of the academy and, despite the requirement to do this research project, she or he has not been invited into the inner sanctum where the real researchers do their work. Not only does she or he not understand historical/political method, but she or he has no sense of the metanarrative that any self-respecting political historian lives by. This is an alien world in which “research” sounds like blah, blah, blah, and the only recourse is to find some data on the topic and summarize it.

Bright students regularly and persistently draw a blank when it comes to following the directions provided for research projects. According to Head (2008), simply identifying what the professor wants is the primary challenge among students. Somehow they are not understanding our directions, perhaps in the same way that the Far Side’s Ginger only hears her name and not the rest of the rebuke. Experts and undergraduates live in different worlds with different metanarratives expressed in different languages. To assume that an undergraduate is going to take our vague command for good research and critical thinking, and run with it, is to risk almost constant disappointment. There is too much that needs to be known about doing a discipline, requiring knowledge and skill that the average student does not possess.

The radical shift in thinking demanded for effective research processes instruction to university students

If we want our students to be skilled researchers, which they certainly need to be to address the ever increasing demands of our information age, we are going to need to rethink education. Some may argue that we have already done so with the development of active learning and constructivist pedagogies intended to put learning into the hands of students. The lecture as the primary form of educating may not be dead, but there is much more of an emphasis on student learning than professorial teaching. Surely that must be good for education. And it is.

But something is missing. Essentially, it is a lack of a conceptualization of the means we must use to ensure student engagement. What, essentially, are we supposed to do to take the emphasis from professor as teacher to the student as learner? What is the underlying philosophy behind “student as learner”? When we espouse the constructivist notion of students finding their own meaning in the information resources they use, what exactly does that entail? There is much said about active, student-involved learning, and it all sounds very good. Yet there is a foundation that is not being built, a basic understanding about what we are supposed to be doing that eludes us.

Just as our existing notions of teaching research processes are not robust enough, some of our plans for active student learning are generally not well enough defined to make the shift to a new method of teaching student researchers that radical enough to succeed. We must seek a new approach.