Chapter Two

Teaming to Learn, Innovate, and Compete

Friday afternoon in a major urban medical center: A patient’s white blood cell count has suddenly spiked upward a few days after major surgery, indicating the possibility of a life-threatening infection. The patient’s breathing is labored, and the color has all but drained from his face. To ascertain the infection’s source, his physician orders a CT scan of the patient’s abdomen and chest. The order is written just after noon.

What happens over the next four days illustrates how much can go wrong when the work is interdependent but teaming doesn’t occur. Unfortunately, hospitals are settings in which teaming failures are frequent and can have life-or-death consequences.

A CT scan is a procedure that unfolds through a series of discrete steps, each carried out by a different specialist. These individuals may not see themselves as part of a team, but the procedure unfolds more smoothly and safely if they coordinate their actions as if they were members of a high-performing team rather than individual specialists completing a series of separate tasks. The procedure’s execution involves the work of several individuals, each with a distinct area of competence and a distinct task to execute. First, for a post-surgical patient not yet able to eat, an expert technician carefully threads a nasogastric (NG) tube into the abdomen through the nose. Next, a different technician, armed with a portable x-ray machine, comes to the bedside to snap a quick image of the patient’s chest and abdomen, as part of a process to ensure proper placement of the tube. This x-ray is then read by a licensed radiologist, who confirms the tube’s placement before liquid is sent through it. Next, a nurse administers a contrast liquid, which must sit for at least an hour, and no more than six, before the patient can be transported to the giant CT scanner, located in its own specialized room. This sequence of tasks, when done well, results in images that help guide patient care.

In most hospitals, the process through which a CT scan procedure unfolds is barely recognized as teamwork. The team in question is a virtual one. Team members don’t meet face-to-face, although each is aware of doing one step in a larger procedure that involves other specialists. A virtual team such as this is teaming when it carefully coordinates member-to-member actions to ensure that each task is done in a timely manner, with the patient’s safety and the physician’s diagnostic ease as its primary concerns.

In this situation, as is unfortunately often the case, coordination was left to chance. A couple of hours after the physician’s request for a scan, the technician came to the bedside to insert the NG tube. Done quickly and expertly, the tube went in relatively smoothly, although not without causing discomfort. Almost an hour and a half later, the x-ray technician came by to produce images with which a radiologist could check the tube’s placement.

At 5:00 PM, with the weekend fast approaching, the tube-placement x-ray had not yet been read by a radiologist. Watching and waiting, the patient’s family asked the on-duty nurse when she would know the results of the x-ray and allow the patient to get her CT scan. The nurse responded with a mystified shrug. From her perspective, radiologists appeared to do things in their own time, not according to her schedule, or even to her patients’ needs. But she agreed to look into it.

At 6:30, the x-ray was read, confirming the tube had been placed correctly some hours earlier and allowing the nurse to administer the contrast liquid. Almost three hours later, the patient, prepared and ready with the contrast dye, had yet to be taken to the scanner. The nurse reassured the family that even if radiology was gone for the weekend, a CT scanner in the emergency room could be used, so the patient would still get his scan. Another hour went by without the necessary specialist to execute this task, and just after 10:00 PM, the patient’s blood pressure dropped precipitously, requiring the nurse to transfer him to the intensive care unit (ICU) for closer observation. At this point, hope of obtaining a CT scan that same day was lost, as the patient was too unstable to be taken to a scanner.

The next day at noon, the patient was sufficiently stable to be transferred out of the ICU and back to the floor where he had started. With the NG tube still in place, the contrast liquid had long since expired and would have to be re-administered for a scan to be completed. Unfortunately, it was now Saturday, and CT scans were done over the weekend only for emergencies.

At 3:00 PM, the nurse reminded the physician, by telephone, that the patient had now had an NG tube inserted for nearly 24 hours. The patient was having trouble breathing, and the tube appeared to exacerbate that difficulty, while also increasing the risk of infection. The surgeon recommended it be removed as soon as possible; after all, it could be reinserted later if a CT scan were to be attempted again. Despite the task’s apparent simplicity, hospital policy required a physician to remove the tube, and so the nurse needed to find a resident physician to do it. Two hours later, a resident was located to remove the tube, which she did in a matter of seconds.

On Tuesday, four days after the original order was written, the entire CT scan procedure was undertaken again, this time successfully. Thus, four full days after the information was first needed, the source of the patient’s infection was identified. Who or what is to blame for this inefficiency and additional risk to the patient? In fact, no one person is at fault. Each competently executed his or her task, and each in the midst of a day comprised of many such tasks for different patients and doctors. These individuals were, for practical purposes, unaware of being members of a temporary and virtual CT scan team, instead thinking of themselves as members of the radiology department or the unit-based nursing team.

Where did the individualistic concept of the work in this situation come from? The hospital, like most, was organized into departments that act as vertical silos and obscure horizontal relationships. Each silo is responsible for training and managing the expert execution of separate, specialized tasks, despite the fact that so many critical procedures involve people and tasks from multiple departments. Ideally, each person, aware of the others’ role and input, would do his or her task at the best time and in the best way to support the entire procedure—this would qualify as teaming. But what more often happens (and what happened in this case), is that each person performs a task as efficiently as possible based on the needs of his or her specialized department. As a result, this CT scan, with direct labor amounting to far less than two hours, failed to be completed over a period of nearly 100 hours.

The silo-like structures that make up many hospitals fail to support the dynamic, real-time teaming needed to carry out many of the procedures through which care is delivered. The person who executes without judgment and acute sensitivity to data in a hospital may harm a patient who needs unique care. Although uncertainty is not exceedingly high, and consequential failure is certainly not routine, the possibility of failure lurks around every corner. This is the nature of complex operations. Everyone understands and seeks to avoid the danger created by interacting parts and the ever-present potential for system breakdowns. Increasingly, therefore, employees in the world’s best hospitals actively engage in teaming. They employ such skills as ingenuity, judgment, intelligent experimentation, and resilience—skills that are difficult, if not impossible, for traditional management approaches to measure. Many organizations and companies recognize the necessity of teaming and continuous learning. Unfortunately, management mindsets and organizational structures have not always shifted accordingly, leaving people engaged in complex interdependent work failing to recognize that interdependence.

In the discussion that follows, I explore the processes and behavioral characteristics that enable teaming and also explain the social, cognitive, and organizational challenges that thwart teaming. Teaming requires awareness, communication, trust, cooperation, and a willingness to reflect. These are seemingly simple attributes, but ones that are too often thwarted by natural human characteristics. I explain the roots of these characteristics, drawing from psychological research, and describe how the teaming process works by overcoming. I end the chapter with four leadership actions that help overcome their effects, enable teaming, and promote organizational learning. Based on decades of data amassed from a range of organizations, with work spanning the Process Knowledge Spectrum, these four actions help cultivate an organizational environment that encourages the behaviors essential to successful teaming.

The Teaming Process

Teaming, by its nature, is a learning process. No sequence of events will unfold precisely the same way twice when people must interact to coordinate ideas or actions, and so participants in such a process are always in a position to learn. Learning in teams involves iterative cycles of communication, decision, action, and reflection; each new cycle is informed by the results of the previous cycles, and cycles continue until desired outcomes are achieved. As team members engage in this cycle, they surface and integrate their differential knowledge, and find ways to effectively use the new collective knowledge to improve organizational routines.

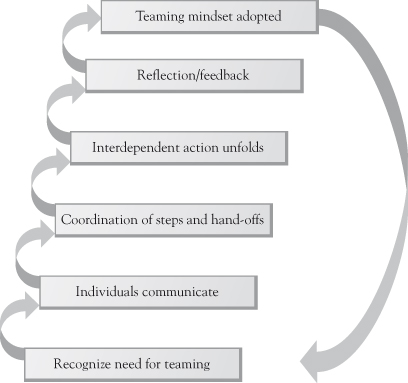

In addition to the essential role of learning, it’s important to understand how teaming gets started and takes hold in settings where interdependent action is needed. Consider the aborted CT scan. This teaming failure occurred due to a lack of interprofessional and inter-task awareness on the part of the individuals involved in the work. Given the realities of different departments with different constraints and priorities, how can cross-functional teaming for both routine and novel tasks be enabled? Figure 2.1 depicts a sequence through which teaming unfolds in coordinated work.

Figure 2.1. Teaming

It starts with recognition. Unless people are aware of their interdependence with others for accomplishing whole jobs, teaming cannot get underway. When people recognize the need for coordination, communication becomes natural, despite departmental silos. Individuals reach out and talk to those with whom they must interact to get their work done well, and this begins the conversation—often very brief—about how to coordinate their respective tasks. Next, the flow of interdependent action unfolds, followed by feedback and reflection that may simply acknowledge each other’s contributions or may instead suggest changes to make things work better going forward. With practice, a teaming mindset becomes more or less second nature, and the recognition step that starts the flow of teaming becomes automatic.

Four Pillars of Effective Teaming

Teaming occurs when people apply and combine their expertise to perform complex tasks or develop solutions to novel problems. Often a fluid process, teaming may involve performing with others, disbanding, and joining another group right away. An episode of teaming ends once some or all of the work is complete, but teaming as a mindset—and approach to work—can continue indefinitely. Teaming is normal in the “temporary organizations” that characterize creative endeavors such as making a film, or in the coordination of complex events, such as producing a professional conference. In such efforts, a mix of planned and spontaneous coordination often brings multiple players together to team.

Proficient teaming often requires integrating perspectives from a range of disciplines, communicating despite the different mental models that accompany different areas of expertise, and being able to manage the inevitable conflicts that arise when people work together. Fundamentally, this is a matter of developing interpersonal skills related to learning (inquiry, curiosity, listening) and teaching (communicating, connecting, clarifying). Teaming is thus both a mindset that accepts working together actively and a set of behaviors tailored to sharing and synthesizing knowledge. Sometimes teaming requires coordinating across distant locations, which both increases the potential for miscommunication and gives rise to new opportunities for innovation. One chemical company I studied used globally dispersed teams to innovate, overcoming various communication barriers to develop new products and processes that offered wider commercial value than those that could be developed in a single location. Whether face-to-face or mediated by communication technologies, successful teaming involves the four specific behaviors listed in Exhibit 2.1.

- Speaking Up: Teaming depends on honest, direct conversation between individuals, including asking questions, seeking feedback, and discussing errors.

- Collaboration: Teaming requires a collaborative mindset and behaviors—both within and outside a given unit of teaming—to drive the process.

- Experimentation: Teaming involves a tentative, iterative approach to action that recognizes the novelty and uncertainty inherent in every interaction between individuals.

- Reflection: Teaming relies on the use of explicit observations, questions, and discussions of processes and outcomes. This must happen on a consistent basis that reflects the rhythm of the work, whether that calls for daily, weekly, or other project-specific timing.

Speaking Up

Candid communication allows teams to incorporate multiple perspectives and tap into individual knowledge. This includes asking questions; seeking feedback; talking about errors; asking for help; offering suggestions; and discussing problems, mistakes, and concerns. Speaking up is particularly crucial when confronting problems or failures of any kind. When people are willing to engage with each other directly and openly, they are better able to make sense of the larger shared work and more likely to generate ideas for improving work processes. Speaking up in this context refers to an interpersonal behavior that allows the development of shared insights from open conversation. It is essential for determining appropriate courses of action in any teaming encounter. Speaking up is also essential for helping people grasp new concepts and methods. Conversing about experiences, insights, and questions builds understanding of new practices and how to perform them. Although many people think of themselves as direct and straightforward, speaking up in the workplace is less common than you might think.

Collaboration

Collaboration is a way of working with colleagues that is characterized by cooperation, mutual respect, and shared goals. It involves sharing information, coordinating actions, discussing what’s working and what’s not, and perpetually seeking input and feedback. Teaming depends on collaborative behaviors within and between departments or organizations. Clearly, without collaboration, teaming easily breaks down. Plans are less well informed, and the execution of plans suffers from the kind of poor coordination illustrated in the hospital example at the start of this chapter. A collaborative attitude is also essential to shared reflection that may occur following coordinated action, because it allows full and thoughtful sharing of expertise and promotes the development of broader and deeper lessons from any experience. Imagine a product development team that doesn’t collaborate with the marketing group and thereby fails to incorporate vital customer preferences or feedback!

Experimentation

Experimentation means expecting not to be right the first time. Borrowed from the literal experiments of scientists, experimentation behavior is a way of acting that centrally involves learning from the results of action. In teaming, experimentation behavior involves reaching out to others to assess the impact of one’s actions on them, and also testing the implications of one’s ideas with respect to what others are thinking. Experimentation is a vital aspect of teaming because of the uncertainty inherent in interdependent action. It’s also a crucial part of learning, of course, as explored later in this chapter in a discussion of the teaming process.

Reflection

Reflection is the habit of critically examining the results of actions to assess results and uncover new ideas. Some teams engage in reflection on a daily basis. Others reflect at a natural break in the project, such as at halftime for sports teams, or when documenting aspects of a patient’s care in a chart after a medical visit. Project teams may explicitly engage in a reflection exercise only when a project is completed. The “after action reviews” conducted by the U.S. Army following military exercises are explicit reflection sessions that use a rigorous structured approach to assess what occurred against what was planned or expected. Reflection does not necessarily mean extensive sessions to thoroughly analyze team process or performance, but rather is often quick and pragmatic. Reflection-in-action, for example, is the critical, real-time examination of a process so it can be adjusted based on new knowledge or, more often, in response to subtle feedback received from the work itself.1 Reflection as a basis for effective teaming is more a behavioral tendency than a formal process. In one study of surgical teams, for example, I found no differences in outcomes for teams with formal reflection sessions, compared to those without such sessions; the teams that succeeded were those that were constantly reflecting aloud on what they were observing and thinking, as a way of figuring out how to work together more effectively.2 For some types of teams, however, it may be more appropriate to wait for outcomes to be available before stopping to reflect on team process, in which case a more structured approach, such as a formal project review, is extremely valuable.

These four behaviors are the pillars of effective teaming. The challenges encountered on the factory floor, in the operating room, and around the glass-topped tables in corporate conference rooms differ significantly in look and feel, as well as in the nature of the work. Yet speaking up, collaboration, experimentation, and reflection are crucial behaviors across these disparate settings. In all of them, leaders who themselves embrace these behaviors make it easier for others to act in ways that support teaming. In addition to these behavioral tendencies, however, leaders must also understand the cyclical, recursive nature of the actual teaming process.

The Benefits of Teaming

One of the most successful product launches in history, Motorola’s 2004 RAZR mobile phone, was the result of successful teaming. Battling fierce global competition in the mobile phone market in 2003, Motorola set out to create the thinnest phone ever released. Electrical engineer Roger Jellicoe was chosen to lead the team. In addition to designing the thinnest phone ever, Jellicoe’s instructions were to create a thing of beauty, a device more like jewelry than a mere utilitarian object. To partner in leading the project, he chose mechanical engineer Gary Weiss, with whom he knew he could work well. Twenty Motorola engineers were invited to join the teaming effort with its ambitious deadline. They came from different groups and locations to collaborate in an otherwise unremarkable facility an hour from Chicago.

Speaking up and experimentation were critical to their success. Neither ideas nor criticisms were held back, as perpetual experimentation and debate led to possibilities and prototypes that were attempted, rejected, altered, tweaked, and refined. A core challenge was the integration of style and technology. Numerous tradeoffs, mostly between appearance and functionality, were considered, and the team resisted easy compromises, pushing instead for elegant solutions to the tough problems they confronted. By experimenting with different configurations, the team hit on the idea of putting the battery next to the circuit board (prior phones had them stacked) to reduce thickness. It worked, allowing the ultra-thin design that gave the phone its appeal and its name. The team’s innovative solution ignored existing human factors experts who had strong views about how wide a cell phone could be to feel right in a person’s hand. Experimenting with a wider mock-up of the phone, the team decided the experts were wrong.3 Reflection was built into the teaming process from the beginning. Meeting every afternoon at 4:00 PM, the group discussed the day’s progress, and reported on the status of such components as the antenna, speaker, keypad, or light source. Scheduled for an hour, the meetings frequently ran past 7:00 PM. These meetings were a primary mechanism for the team’s focused conversation and debate. Reporting on failures as easily as successes and breakthroughs, everyone was engaged in the process of offering ideas and criticisms. Industrial designer Chris Arnholt, whose slim clamshell design was crucial to the team’s success, had brought sketches to the meetings only to discover that his initial ideas for the style of the phone were neither practical nor easily understood by the engineers. In the teaming that ensued, Arnholt and the engineers jointly decided on a design that worked.

The project’s biggest setback occurred when it missed its ambitious initial deadline, but the result, only a few months later and still within a fast time line, was worth waiting for: Motorola unveiled the RAZR, the thinnest phone ever produced, before the end of 2004, and went on to sell 50 million RAZR mobile phones within the next two years and 110 million over four years.4

The RAZR story showcases the positive relationship between a teaming mindset and behaviors and project performance. Team members, from multiple areas of expertise, jumped in wholeheartedly to work together to do something new, exciting, and remarkable. Many organizations rely on teaming to keep up with today’s fast-paced, global environment. Consider how much of the work in today’s organizations requires people to make decisions together, to reflect the different needs and different information each brings, in response to unforeseen or complex problems. Theoretical and empirical research has identified several benefits of teaming for organizations and their staff. These benefits largely fall into two categories: better organizational performance and more engaging and satisfying work environments.

Performance

Whether a new product development team made up of designers, marketers, and engineers, or a cardiac surgery team made up of surgeons, nurses, perfusionists, and anesthesiologists, the benefits of teaming for organizational learning and performance are significant. In particular, teaming helps organizations develop new routines and implement new technologies to meet the demands of a changing context. These kinds of organizational changes call for teaming because they require understanding and coordination across departments and disciplines. As Richard Hackman and I have argued, teams are an organization’s best change agents.5 Most models of change management call for a change leadership team or a change implementation team to promote better ideas and greater buy-in. But it shouldn’t stop there. What really matters is not just the creation of a team, but how those selected work with each other and with other members of the organization to help create change in a dynamic, learning-oriented way. These change agents must listen, coordinate, and continually make adjustments in plans to accommodate each other’s input. This naturally gives rise to uncertainty, and requires attention and sensitivity to feedback. The core behaviors of teaming thus drive organizational performance by facilitating the creation of new knowledge, new processes, and new products.

Performance improves when new knowledge is put to good use, also enabled by teaming. In a study of cardiac surgery teams, explored in greater detail in Chapter Three, my colleagues and I showed that teaming behaviors led to far more successful implementation of a new technology, compared to surgical teams with a more top-down control approach. Through teaming people were able to figure out what processes needed to be changed for the new procedure to work.6 Similarly, I later studied dozens of quality improvement teams in 23 hospital ICUs and found that teaming and learning led to measurable improvement. Although going to the research literature to find the latest medical knowledge was important, the teams that best succeeded in implementing change were those who engaged in the interpersonal learning behaviors crucial to teaming. They communicated, coordinated, asked questions, listened, and experimented—both within and outside of the team’s boundaries. This built knowledge and enthusiasm, which encouraged team members to make the behavior and process changes needed to improve patient care.7 In both studies, we found that psychological safety, explored in detail in Chapter Four, enabled teaming and learning, and led to better performance. I have found similar results in work settings other than hospitals, including manufacturing, product development, and even the design and construction of buildings.

Engaged Employees

Teaming has a positive effect on people’s experience at work. Interacting directly with people who have different knowledge and skills makes work more interesting, enriching, and meaningful. In organizations where teaming is common, employees learn from each other, enjoy a broader understanding of the work and how it gets done from start to finish, and can better see and act on opportunities for improvement. For example, Simmons Mattress Company, discussed in more detail in Chapter Eight, introduced team training to raise employee technical and interpersonal skills, which in turn led to greatly increased awareness of the contributions of other employees working in different parts of the manufacturing process. Once everyone began to understand what unseen colleagues did all day, why it was difficult, and how the combined tasks came together to make an entire mattress, not to mention an entire sales and distribution operation, they enjoyed the work more, and were also more productive.8

Teaming also benefits an organization by allowing people to combine their knowledge to create new products or implement new procedures. Teaming allows organizations to benefit from teams of experts working together to improve quality, reduce operating costs, and enhance customer satisfaction. Through teaming, diverse employees representing different attitudes, values, and beliefs perform in an environment of mutual respect, shared knowledge, and shared goals. Imagine all of this work occurring in iterative, self-regulating cycles of improvement and innovation that guarantee organizational success well into the future!

If only it were so easy.

Social and Cognitive Barriers to Teaming

I’ve spent an inordinate amount of time studying people in hospitals. People working in hospitals face some particularly challenging work environments. Demands for coordination are great, time is tight, and the stakes are high. As a result, the rest of us can learn a lot from understanding how the best hospitals manage these inherent challenges effectively. Medical knowledge and best-care practices, which are vast and constantly updated, must be consulted to inform high-stakes, cross-disciplinary communication and action, often under immense time pressure. And, unfortunately, even in a hospital—a setting that calls for nearly constant teaming—cooperation and trust face many challenges.

Consider a busy emergency room. At any moment, a patient with life-threatening, possibly unprecedented, symptoms might arrive by ambulance. Immediately, specialists from several departments—reception, nursing, medicine, laboratory, surgery, pharmacy—must coordinate their efforts if the patient is to receive effective care. These people must resolve conflicting priorities and opinions quickly. They may or may not have previously worked together as a team and most likely some are less experienced than others. Nonetheless, personalities must mesh rather than clash. And people must rely on their collective judgment and expertise, rather than on management direction, to decide what to do. It shouldn’t surprise anyone that these busy clinicians sometimes make the wrong call. But the true problem is not just that they might sometimes get the medical diagnosis wrong. It’s that they might do so by failing to work together effectively.

Serious Work Means Serious Tension

As Wynton Marsalis, artistic director for Jazz at Lincoln Center, says of his work with other jazz musicians: “There are always tensions that come up. Part of working is dealing with tensions. If there’s no tension, then you’re not serious about what you’re doing.”9

Certainly, teaming sometimes goes well in today’s organizations. People recognize their interdependence and work effectively together. They offer their ideas freely, carrying out their part of the collective work and responding thoughtfully to others’ ideas and actions. At other times, however, teaming breaks down and coordination fails. Signals get crossed or conflicting opinions derail the conversation. Many teaming efforts—whether in routine, complex, or innovation operations—start with high hopes, only to falter. What are some of the obstacles to effective teaming?

People Don’t Always Get Along

Teaming requires participants to productively manage the inevitable conflicts that arise when people work together in serious endeavors. Well-functioning teams are powerful, but rarely static. They are as hard to create as to sustain. Many tasks are technically complex to begin with and present interdependencies that make them even more so. Personality, leadership, resource allocation, differences in knowledge and background—any problems encountered in these areas can give rise to misunderstanding or dysfunction. Fear is a major barrier to teaming, as discussed in Chapter Four. Similarly, lacking a clear, shared objective also inhibits the effortful behaviors that comprise teaming. Organizational factors, such as bureaucracy, layers of management, or contradictory incentive systems, also get in the way. Teaming is as difficult as it is necessary.

It’s far easier for an individual to have a clear and well-bounded task to do over and over again than to figure out how to carry out more complex and interdependent work with others. Interdependent work requires coordination through back-and-forth communication to do it well. When we are interdependent, it necessarily means we cannot do everything that must be done alone. This is a rather humbling realization, and many shy away from embracing it. It can be hard for people to muster both the humility and the genuine curiosity that is needed to really learn from others. It turns out that cognitive, interpersonal, and organizational factors all get in the way of effective learning in teams. It’s a cruel irony—our success depends upon effective collaboration and learning, the essence of teaming, but these don’t come naturally either for individuals or the social systems we create. The following sections examine the cognitive and structural factors that inhibit teaming.

Silence Is Easier Than Speaking Up

When leaders fall into a default “do it my way” management style, it silences nearly everyone except the person with the loudest voice or the largest office. But silence in today’s economic environment is deadly. Silence means good ideas and possibilities don’t bubble up, and problems don’t get addressed. Silence stymies teaming. Most people feel a need to manage what I call interpersonal risk—a risk that others will think less of them—so as to minimize harm to their image, especially in the workplace, and especially in the presence of bosses and others who hold formal power. One way to minimize risk to one’s image is simply to avoid speaking up unless you’re sure you’re right, avoid admitting mistakes, and, of course, never ask questions or raise tentative ideas that you’re not sure have merit. Although this approach may work for individuals—protecting them from being seen by others in an unfavorable light—it is clearly problematic for organizations and their customers.

Shhhh, Here Comes the Boss

Research shows that hierarchy, by its very nature, dramatically reduces speaking up by those lower in the pecking order. We are hard-wired, and then socialized, to be acutely sensitive to power, and to work to avoid being seen as deficient in any way by those in power. Most of this behavior is unconscious. As a result, in most organizations, even if leaders at the top of the hierarchy say they welcome employee feedback, and even if people have the knowledge and training to say something of importance, they still may remain silent out of fear of negative consequences.10

Research does show, however, that leaders can promote speaking up through particular behaviors and actions.11 Most important, when leaders explicitly communicate that they respect employees, it makes it easier for employees to volunteer their knowledge. More specifically, by acknowledging the need for the knowledge and skills that others bring, leaders issue a credible invitation for people to speak up. Mistakes, in particular, require active encouragement if they are to be reported or discussed. In sum, speaking up is not natural in organizations, but it can and does happen, particularly when leaders actively model, invite, and reward candor and openness. In contrast, inaccessibility or a failure to acknowledge vulnerability can contribute to a reluctance to incur the interpersonal risks of teaming behavior.

Disagreement

Speaking up brings challenges, too. As soon as people speak up and communicate freely with one another, there is bound to be disagreement and sometimes seemingly irresolvable conflict. The problem with disagreement is not that it occurs; the problem is the sensemaking in which people spontaneously engage when disagreement occurs. All of us have at one point or another spontaneously attributed unflattering motives, traits, or abilities to those who disagree with our strongly held view. In such cases, we might say something like “She doesn’t get it” or “He’s just out for himself.”

Our own views seem so right that others’ disagreement seems irrational, or worse, deliberately unhelpful. This is why, as research on social cognition helps explain, conflict can be a roadblock to effective teaming. But it doesn’t have to be. Rather than wasting precious time and eroding personal relationships, conflict can be an opportunity for building new understanding, respect, and trust. It helps to consider two common cognitive errors identified by psychologists, naïve realism and the fundamental attribution error. 12

Naïve Realism

We are all prone to naïve realism, a term coined by psychologist Lee Ross, which is a person’s “unshakable conviction that he or she is somehow privy to an invariant, knowable, objective reality—a reality that others will also perceive faithfully, provided that they are reasonable and rational.”13 So, when others misperceive our “reality,” we conclude that it must be because they are unreasonable or irrational and “view the world through a prism of self-interest, ideological bias, or personal perversity.”14 And therein lies the trouble.

One outcome of naïve realism is that people tend to see their own views as more common than they really are, leading them to falsely assume that others share their views. For example, someone might say, “We need to dramatically curb carbon emissions to prevent further global warming.” Or, “Everyone knows we have the best medical system in the world.” Social psychologists call this the false consensus effect. And such assumptions usually go unnoticed—until unexpectedly refuted when someone disagrees. This means, if someone replies, “I don’t think human activity is contributing to climate change. Temperature fluctuations have gone on for millennia,” the original speaker may spontaneously conclude that the responder is closed-minded, wrong-headed, or worse. Similarly, someone might respond to the second statement, “If we have the best medical care, why do we rank 36th in the world for life expectancy?” while privately viewing the original speaker as ignorant or misguided. For most people, finding out that a friend or colleague disagrees with us on something we care about is usually an unpleasant surprise.

The Fundamental Attribution Error

The second cognitive error that makes it hard to cope with conflict productively was dubbed the “fundamental attribution error” by Lee Ross.15 The term describes our failure to recognize situational causes of events and our tendency instead to overattribute individuals’ personality or ability as likely causes. An outgrowth of this cognitive error is that we tend to explain others’ shortcomings as related to their ability or attitude, rather than to the circumstances they face. That is, we blame the people for things that go wrong—not the situation. Every parent of more than one child has heard, “Don’t blame me, it’s his fault.” In the workplace, the same thing happens, even if the words are less direct and unambiguous.

It’s almost amusing to realize that we do exactly the opposite in explaining our own failures. That is, we spontaneously attribute them to external factors. For example, if we show up late for a meeting, we may blame circumstances outside our control, like rush-hour traffic. If a subordinate is late for a meeting, however, we think he is not committed to the project, or that he’s disorganized. On both sides of the attribution coin, we make judgments effortlessly—remaining largely unaware that there was an alternative cause to consider. As natural and sometimes humorous as this asymmetry is, it creates a couple of problems for teaming. First, when we blame others for things that go wrong, productive discussion of the issues is less likely to occur. Worse, we tend to believe we have sized up the situation and its causes accurately. Second, we begin to think less of others, and then may be less motivated to engage wholeheartedly in teaming with them.

This error is called “fundamental” because it’s essentially universal. All of us do it, and we do it without thinking. In fact, it takes cognitive effort to override it and think, “I wonder if she ran into unexpected traffic on the way to this meeting?” This means remaining open—deliberately interrupting the attributional process. If we really paused to think about it more often, we’d probably laugh at ourselves for so quickly jumping to unkind conclusions. But when people don’t stop to challenge the unflattering causal attributions they make about others’ ability or intentions, teaming obviously suffers.

Tension and Conflict

The fundamental problem with disagreements, and the cognitive structures that exacerbate them, is that they create tensions in a group. Tensions are to be expected when teaming. Although rarely fun, tensions are not always bad. They can evoke creativity, sharpen ideas, and refine analyses. But there’s a catch: patience, wisdom, and skill are needed to transform tensions into positive results. This is because most of us naturally resist tensions and the conflict they invariably bring.

When Conflict Heats Up

Nobody likes pushback. We naturally prefer others to agree with us. When we resist conflicting points of view or don’t have the skills necessary to transform tensions into creativity and excellence, it’s easy to fall back into the old, top-down mindset. Collective action is always easier when there is someone clearly in charge to settle differences, quash disagreement, and defuse conflict. When the stakes are high and conflicting opinions meet uncertainty, trying to remain cool and logical can seem like a losing game. Frank conversations must occur for teaming to succeed. Understanding the cognitions, behaviors, and reactions that underpin conflict is vital to supporting teaming.

Hot and Cool Cognition

Research by cognitive psychologists Janet Metcalfe and Walter Mischel showed that we each have two distinct cognitive systems through which we process events.16 Trying to understand the mechanisms that allow people to delay gratification—a crucial ability for everything from goal achievement to weight control—Metcalfe and Mischel identified two types of human cognition, which they called “hot” and “cool,” as shown in Table 2.1. The hot system, when engaged, triggers people to respond emotionally and quickly. In this case they are often said to speak or act in the heat of the moment. The cool system, in contrast, is deliberate and careful. When using our cool system, we can slow down and gather our thoughts. The cool system is the basis for self-regulation and self-control. Consequently, it is a necessary tool for teaming effectively when (not if) conflict occurs.

Table 2.1: Hot Versus Cool Systems

| Hot System | Cool System |

| Emotional | “Know” |

| “Go” | Complex |

| Reflexive | Reflective |

| Fast | Slow |

| Develops Early | Develops Late |

| Accentuated by Stress | Attenuated by Stress |

| Stimulus Control | Self-Control |

Source: Metcalfe, J., and Mischel, W. “A Hot/Cool System of Delay of Gratification: Dynamics of Willpower,” Psychological Review 106, no. 1 (1999). Reprinted with permission of the American Psychological Association.

Spontaneous Reactions

Teaming breaks down when conflict heats up; rather than triggering new creative thinking, it works instead to slow progress. Often, individuals will go back and forth, repeating the same points over and over again. As summarized in Table 2.2, conflicts typically heat up when three conditions are present: controversial or limited data that are subject to differing interpretations, high uncertainty, and high stakes. Conversations can get especially heated when people hold different values or belief systems, or have different interests and incentives. This can make aspects of the conflict hard to discuss productively, because people often hesitate to mention the personal gain they anticipate from one of the potential decision outcomes.

Table 2.2: Contrasting Cool and Hot Topics

| Cool Topics | Hot Topics | |

| Data | Accessible, relatively objective, conducive to testing of different interpretations | Controversial and/or inaccessible, interpretation is highly subjective, different interpretations hard to test |

| Level of Certainty | High* | Moderate to Low |

| Stakes | Low to Moderate | High |

| Goals | Largely shared | Differ based on deeply-held beliefs, values, or interests |

| Discussion | Reasonable, fact-based collegial | Often emotional, lack of agreement about which facts matter and what they mean, veiled personal attacks likely |

*High certainty situations involve present actualities or near-term possibilities that can be illuminated relatively easily through facts and analyses.

Source: Edmondson, A. C., and Smith, D. M. “Too Hot to Handle? How to Manage Relationship Conflict,” California Management Review 49, no. 1 (2006): 6–31. © 2006 by the Regents of the University of California. Reprinted by permission of University of California Press.

These conditions were present in the senior management team of a company I’ll refer to as Elite Manufacturing to protect confidentiality. I studied eight senior managers at Elite over several months as they met to diagnose and design corporate strategy.17 Ian McAlister, the head of Elite’s struggling core business, and Frank Adams, the president of a small, successful subsidiary with less expensive product lines, became embroiled in a conflict that quickly turned personal.

Adams spoke first. Looking directly at McAlister, he told the group that future industry growth was in low-end inexpensive products. This meant that investing in the core business run by McAlister was a losing venture. McAlister, who naturally felt attacked by Adams’s proposal, countered that his own data suggested just the opposite: the company needed to invest more in the core business to regain appeal and brand recognition for the majority of customers who valued quality and design. Already, the conflict was heating up.

As often happens, especially in ambiguous situations, conflicting interpretations of the same facts were used to fuel conflicting truths. To Adams, the data plainly showed that the core business was fundamentally flawed; obviously, only the lower end of the market was growing. McAlister, however, rejected Adams’s conclusion. In McAlister’s view, the data indicated that smart, attractive products were needed to expand market share in the lucrative high end of the market, consistent with Elite’s long (and mostly successful) history. According to McAlister, it was only a matter of time and commitment. Looking at the same “reality,” the two executives had arrived at very different conclusions about how to deal with an uncertain future full of risk. As the meeting wore on, Adams and McAlister continued to argue, fanning the flames of conflict still higher, neither budging from his original position until they found themselves at a standoff.

When conflicts reach an impasse, the discussion often starts to get personal. Adams believed that McAlister’s wrongheaded view was merely a façade for increasing his own power in the company. Unsurprisingly, McAlister had reached the same conclusion about Adams. Both had fallen victim to the fundamental attribution error. More generally, whether blaming each other’s motives, character, or abilities, people in the midst of a tough conflict like this one often silently blame someone else for the lack of progress on their shared task.

How can managers seeking to learn from different perspectives overcome the teaming challenges encountered by Elite’s executives? In other words, how do we cool hot topics in fast-paced conversations about important topics? Exhibit 2.2 lists four strategies for mitigating conflict and ensuring the cooperative effort needed to successfully team.

- Identify the Nature of Conflict: Though a difference of opinion about a product design or a work process is useful, personal friction and personality clashes are counterproductive. Understanding the differences between types of conflict allows leaders to better manage contentious exchanges.

- Model Good Communication: Good communication when confronting conflict, especially heated conflict, combines thoughtful statements with thoughtful questions, so as to allow people to understand the true basis of a disagreement and to identify the rationale behind each position.

- Identify Shared Goals: By identifying and also embracing shared goals, teams are able to overcome the fundamental attribution errors that erode respect and instead develop an environment of trust.

- Encourage Difficult Conversations: Through good communication, as just defined, it’s useful to engage in authentic conversations that help build resilient relationships and put aside ideological and personal differences.

Identifying Task and Relationship Conflict

Management researchers who study conflict in teams have concluded that conflict is productive, as long as teams stay away from the personal and emotional aspects of conflict. Task conflict—a difference of opinion about the product design—is useful. Relationship conflict—personal friction or emotionality—is counterproductive and should be avoided.18 These researchers assert that task conflict improves the quality of decisions by engaging different points of view, while relationship conflict harms group dynamics and working relations.

This, of course, sounds like great advice. The problem is, it’s too simple. First, as we just saw at Elite, it’s far easier said than done. Adams and McAlister were trying to stay away from emotions and avoid personal friction. Neither one brought past grudges or suspicions to the table deliberately. They wanted to focus on the facts, and they intended to be guided by logic and analysis in arriving at a sensible team decision. Despite these intentions, they still ended up with raised voices, frustration, and concerns about each other’s motives. Why does this so often happen in well-meaning attempts at teamwork?

Many conflicts arise from personal differences in values or interests but are presented as professional differences in opinion. For example, if some executives believe that good design sells products (as McAlister did) while others believe that customers are primarily motivated by price (as Adams did), a conflict that pits design against price is a conflict of values. Values are beliefs we hold dear, and when our values are dismissed by others, even inadvertently, we react with strong emotions. Adams was proud of his subsidiary’s rising sales. McAlister was proud of the parent company’s design heritage. Each believed that other reasonable people would share their values—naïve realism at work—and each was disappointed to find he was wrong. Similarly, when personal interests are involved—one department may become the target of layoffs—emotions are hard to curb.

In contrast, calm and cool resolution of differences is easy when the problem is pure task conflict. In such cases, disagreement readily submits to resolution through facts and reasoning. Differences of opinion can be adjudicated through calculations or analyses that unambiguously assess the different options under consideration. In these situations, the advice to steer clear of relationship conflict and focus on task conflict is both feasible and sensible. However, when conflicts pit values against each other, it can be not only necessary but also fruitful to engage in thoughtful discussions of the emotions, values, and personal struggles behind the conflicts. When done skillfully, this kind of conversation allows meaningful progress on important challenges and debates, some that lie at the heart of a company’s strategy.19

Good Communication and Shared Goals

Teaming, by its very nature, brings people from different backgrounds together to solve problems, coordinate processes, come up with new ideas, and deliver innovations. Interpersonal interactions can be engaging and intense. It is not surprising, given this intensity, that relationship conflict shows up uninvited despite leaders’ best efforts to avoid it. It shows up in the midst of seemingly task-focused discussions. At Elite, the problem to be addressed was whether growth could be achieved by raising the quality of design or lowering product prices. What happened next took deliberate leadership.

With help from my colleague, skilled interventionist and author Diana Smith, the team at Elite Manufacturing switched gears. These senior executives were able to work together to learn and practice the skills for managing conflict effectively. First, McAlister and Adams each honestly examined to what degree their positions reflected what they believed best for the company and how much self-interest was involved. They also considered how their personal values influenced their views. Adams, a relative newcomer to Elite, was able to listen to McAlister, an “old-timer,” speak about the company’s long-term value of integrity in design. McAlister was proud of Elite’s history. Several other managers who had been at Elite for many years chimed in with stories of Elite’s having successfully weathered prior crises and times of slow growth. They also spoke of iconic designs that had made the company great.

After listening thoughtfully, Adams expressed appreciation for Elite’s history and reputation. That was why he’d wanted to come to Elite in the first place. Adams said he understood why the core business was so important to McAlister. But he wanted McAlister and the others to understand his experience at a previous company, where lean operations and streamlined management structures had produced phenomenal results.

Now it was McAlister’s turn to listen. After Adams had shared the role he’d taken in growing a division at his previous company, McAlister expressed renewed respect for Adams’s track record and strategic agility. That’s why the entire leadership team had wanted to bring him on board. The tension leaving the room was like air escaping from a balloon. By sharing the personal experiences and deeper rationales behind their respective positions, McAlister and Adams began to build respect and trust. Each man found that he could in fact be curious about what motivated the other to take his position. Another executive, who had not spoken up until that moment, pointed out that Elite was in tricky territory that differed in some fundamental ways from the challenges faced in the past. Another suggested listing crucial topics: How will we compete? How will we reduce costs? Do we need to redefine Elite’s core mission?

The managers learned how to reflect on and challenge their spontaneous emotional reactions to disagreement. They became willing to experiment with reframing the situation, which meant looking at the issue from a different perspective. Reflecting and reframing are effective ways to cool a hot conflict. When practiced, they help to build a cooling system that’s able to interrupt emotional hijackings before they erupt and bring a team’s progress to a halt.

Encourage Difficult Conversations

Engaging conflict productively cannot be accomplished by avoiding emotions and personal differences. Openness is required.20 This is a teaming skill that starts with willingness to explore rather than shy away from different beliefs and values. It requires acknowledging emotional reactions openly and exploring what led to them, rather than pretending they don’t exist. It requires recognizing the inseparability of task and relationship conflicts in knowledge-intensive work in uncertain contexts. Team members must understand that “winning” the argument does not usually produce the best solution. Instead, the best solutions usually involve some integration and synthesis of differences. When people put their heads together, truly intent on learning from one another, they can almost always come up with a solution that is better than anyone could have come up with alone. This is teaming at its best.

Authentic communication about how we think or what makes us tick helps to build the genuine, resilient relationships that are crucial to effective teaming. Once McAlister and Adams realized that neither of their views had the corner on truth, they were willing to put aside ideological and personal differences, at least temporarily, to think about a new range of issues with their colleagues. But this took guidance and leadership skill.

Leaders who do not fully grasp the concept that conflict of some sort is necessary and even desirable to teaming are destined to fail in all but the most routine of work environments. To close the gap between how we want to lead and how we actually do lead, more of us need to learn the leadership skills to engage conflict directly and effectively. This takes commitment, patience, a willingness to make mistakes, self-awareness, and, of course, a sense of humor. At the very least, it involves a willingness to examine one’s own role in a situation, even in a heated disagreement, and to wonder: “How am I contributing to the problem here?”

Leadership Actions That Promote Teaming

Teaming and learning do not happen automatically. Instead, they require coordination and some structure to ensure that insights are gained from members’ collective experience and used to guide subsequent action. As research demonstrates across varied cases and settings, teaming and learning both depend on the deliberate exercise of leadership. It takes leadership to understand and resolve conflict and to instigate thoughtful conversations about errors. It takes leadership to adhere to process discipline and to help people remember to explore and experiment. In short, leadership is needed to help groups build shared understanding and coordinate action.

In nearly two decades of research, I’ve discovered that successful teaming efforts have followed strikingly similar paths, even across very different settings. Though the organizations I’ve examined operate in a range of environments and include enterprises in varied locations on the Process Knowledge Spectrum, many experienced similar failures when attempting to facilitate a significant transition or implement a novel technology. To help organizational leaders, I’ve synthesized both the positive and negative lessons I’ve learned from my research into four leadership actions. Presented in Exhibit 2.3, these actions form the basis of a way of leading I call organizing to learn. As explained in Chapter One, organizing to learn is a framework for creating an organizational environment conducive to teaming and learning activities, such as accessing collective knowledge, integrating diverse expertise, and analyzing uncertain outcomes.

- Action 1: Frame the situation for learning.

- Action 2: Make it psychologically safe to team.

- Action 3: Learn to learn from failure.

- Action 4: Span occupational and cultural boundaries.

These four actions, outlined in the following sections and discussed in much greater detail throughout Part Two, are not solely practices intended for teaming and learning. In fact, these individual practices translate directly to improved leadership and performance under nearly any circumstance. Taken together, however, they form the foundation for leading a successful teaming effort and provide a path forward for integrating learning into everyday execution.

Framing for Learning

Framing is crucial for leading the kind of change necessary to engage people as active learners. Leaders seeking to facilitate teaming and produce organizational learning must frame their project in a way that motivates others to collaborate. Researchers agree, however, that many of our spontaneous frames at work are inherently about self-protection.21 These self-protective frames dramatically inhibit opportunities to collaborate, learn, and improve. However, people can learn to reframe and shift from spontaneous, self-protective frames to reflective, learning-oriented frames. Doing so involves interdependent team leaders, empowered teams, and an aspirational purpose. Chapter Three explores the process of framing and provides a number of practical framing tactics to help leaders seeking to facilitate teaming and promote collective learning.

Making It Psychologically Safe

An environment of psychological safety is an essential element of organizations that succeed in today’s complex and uncertain world. The term psychological safety describes a climate in which people feel free to express relevant thoughts and feelings without fear of being penalized. Although it sounds simple, the ability to ask questions, seek help, and tolerate mistakes while colleagues watch can be unexpectedly difficult. Because coordinating and integrating complex tasks requires people to ask questions, share thoughts openly, and act without excessive concern about what others think of them, teaming flourishes with psychological safety and diminishes without it. Chapter Four includes information on how team leaders can shape and strengthen the teaming and collective learning processes by fostering an environment of psychological safety.

Learning to Learn From Failure

An essential, if difficult, teaming activity is learning from failure. Failure, broadly defined, encompasses both the small and large events in organizations that don’t go as planned. Examples include a defect occurring in an assembly process, a new drug failing in clinical trials, or a strategy meeting breaking down. Learning from failures of all kinds is as vital as it is difficult. No one wants to look bad in front of his or her peers, and few of us want to admit failure. Yet failure is a necessary aspect of both teaming and organizational learning. As Chapter Five explains, failures of many kinds offer the chance to gain new insights into how to improve a process or product. The secret for organizations is to figure out how to gather and act on, rather than ignore or suppress, this potentially valuable information.

Spanning Knowledge Boundaries

Teams that succeed today don’t merely work well around a shared conference table; they also have the ability to collaborate across boundaries and reach people who have the knowledge and information to help them apply resources effectively. Rapid developments in technology and the greater emphasis on globalization have dramatically increased the significance of boundary spanning in today’s work environment. The information technology that has allowed us to communicate instantaneously across continents, however, sometimes leaves us with a false sense of confidence that productive teamwork is merely a click away. Education and other socializing processes lead people to favor their own group, discipline, location, or department. Ignoring such boundaries can easily blindside even the most well-intentioned teaming efforts. Chapter Six explores the various kinds of boundaries that people must span when teaming and how they can learn to collaborate despite different points of view, skill sets, and locations.

Leadership Summary

For teaming to work, participants must be willing to ask questions, offer suggestions, and voice concerns. This often includes coordinating across dispersed locations and communicating across different areas of expertise. Though seemingly simple, such collaborative efforts are often tested by many of our natural characteristics. Cognitive, interpersonal, and organizational factors get in the way of effective teaming. Psychological biases and errors that reduce the accuracy of human perception, estimation, and attribution create group tensions and interpersonal conflict. Conflict, however, is a natural part of teaming.

Productively engaging the conflict that teaming creates is done not by avoiding emotions and personal differences, but rather by developing a willingness to explore different beliefs and values. Leaders hoping to employ teaming, and to promote the learning that accompanies it, need to develop the leadership skills necessary to engage conflict effectively. Doing so has very real consequences for the way teaming occurs, or fails to occur, in work teams of all kinds. Fostering an atmosphere in which trust and respect thrive, and flexibility and innovation flourish, pays off even in the most deadline-driven work settings.

These leadership skills, challenging and rare as they may be, are crucial for such teaming activities as accessing collective knowledge, integrating diverse expertise, and analyzing uncertain outcomes. The four leadership actions presented at the end of this chapter, and explained in depth in Part Two, help cultivate an organizational environment that encourages the behaviors essential to successful teaming and organizational learning. These actions form the foundation of a way of leading I call organizing to learn. Organizing to learn is a leadership framework that optimizes teaming and ensures the cooperative learning needed for improvement and innovation.

LESSONS AND ACTIONS

- Although teaming is imperative in today’s organizations, neither teams nor organizations naturally do it well.

- Successful teaming requires four behaviors: speaking up, collaboration, experimentation, and reflection.

- These behaviors are enacted in iterative cycles. Each new cycle is informed by the results of the previous cycle. Cycles continue until desired outcomes are achieved.

- There are several benefits to teaming. These benefits fall into two categories: better organizational performance and more engaging and satisfying work environments.

- The collaborative behaviors required by teaming, however, create group tensions and conflict. Leaders who do not grasp the concept that conflict is desirable to teaming and who do not learn the skills necessary to confront conflict are destined to fail.

- To moderate conflict, leaders should identify the nature of the conflict, model good communication, identify shared goals, and encourage difficult conversations.

- Due to the challenges of teaming, particular attention should be paid to the role of leadership. The mindset and practices of organizing to learn enable both teaming and learning.

- Successfully implementing an organizing-to-learn mindset involves four actions: framing for learning, making it psychologically safe, learning to learn from failure, and spanning occupational and cultural boundaries.

Notes

1. D. Schön, The Reflective Practitioner (New York: Basic Books, 1983).

2. A. C. Edmondson, R. Bohmer, and G. P. Pisano, “Disrupted Routines: Team Learning and New Technology Adaptation,” Administrative Science Quarterly 46 (2001): 685–716.

3. A. Lashinsky, “RAZR’S Edge,” Fortune on CNNMoney.com, 1–6. http://money.cnn.com/2006/05/31/magazines/fortune/razr_greatteams_fortune/index.htm.

4. Ibid; see also http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Motorola_RAZR.

5. J. R. Hackman and A. C. Edmondson, “Groups as Agents of Change,” in Handbook of Organizational Development, ed. T. Cummings (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2007), pp. 167–186.

6. Edmondson et al., “Disrupted Routines.”

7. A. L. Tucker, I. M. Nembhard, and A. C. Edmondson, “Implementing New Practices: An Empirical Study of Organizational Learning in Hospital Intensive Care Units,” Management Science 53, no. 6 (2007): 894–907.

8. A. C. Edmondson and T. Casciaro, “Leading Change at Simmons,” HBS Case No. 9–406–047 (Boston: Harvard Business School, 2006).

9. E. McGirt, “How I Work.” Fortune on CNNMoney.com (15 March 2006). http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/2006/03/20/8371781/index.htm.

10. J. R. Detert and A. C. Edmondson, “Implicit Voice Theories: Taken-For-Granted Rules of Self-Censorship at Work,” Academy of Management Journal 54, no. 3 (2011): 461–488.

11. See especially A. C. Edmondson, “Speaking Up in the Operating Room: How Team Leaders Promote Learning in Interdisciplinary Action Teams,” Journal of Management Studies 40, no. 6 (2003): 1419–1452.

12. See, for example, R. Nisbett and L. Ross, Human Inference: Strategies and Shortcomings of Social Judgment (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1980).

13. L. Ross, “The Intuitive Psychologist and His Shortcomings,” in Advances in Experimental Psychology, Vol. 10, ed. L. Berkowitz (New York: Academic Press, 1977), p. 405.

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid.

16. J. Metcalfe and W. Mischel, “A Hot/Cool System of Delay of Gratification: Dynamics of Willpower,” Psychological Review 106, no. 1 (1999): 3–19.

17. The Elite case was discussed at some length in A. C. Edmondson and D. M. Smith, “Too Hot to Handle? How to Manage Relationship Conflict,” California Management Review 49, no. 1 (2006): 6–31.

18. See A. C. Amason, “Distinguishing the Effects of Functional and Dysfunctional Conflict on Strategic Decision Making: Resolving a Paradox for Top Management Teams,” Academy of Management Journal 39, no. 1 (1996): 123–148; and K. M. Eisenhardt, J. L. Kahwajy, and L. J. Burgeois, “How Management Teams Can Have a Good Fight,” Harvard Business Review 75, no. 4 (1997): 77–85.

19. For more depth on this important topic, see pioneering work by Diana McLain Smith, Elephant in the Room: How Relationships Make or Break the Success of Leaders and Organizations (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2011).

20. For a superb guide to this topic, see D. Stone, B. Patton, S. Heen, and R. Fisher, Difficult Conversations: How to Discuss What Matters Most, 10th Anniversary Ed. (New York: Penguin Books, 2010).

21. J. R. Detert and A. C. Edmondson, “Implicit Voice Theories: Taken-for-Granted Rules of Self-Censorship at Work,” Academy of Management Journal 54, no. 3 (2011).