Chapter Five

Failing Better to Succeed Faster

Teaming rarely unfolds perfectly, without any bumps, glitches, or failures. This means that the ability to learn from failure is an essential teaming skill. And although most leaders say they understand the importance of failure to the learning process, not many truly embrace it. In my research, I’ve found that even companies that have invested significant money and effort into becoming learning organizations struggle when it comes to the day-to-day mindset and activities of learning from failure. Managers in these companies were highly motivated to help their organizations learn in order to avoid recurring failures and mistakes. In some cases, they and their teams had devoted many hours to after-action reviews and post-mortems. Even these types of painstaking efforts fall short, however, if managers or leaders think about failure the wrong way.

Most executives I’ve talked to believe that failure is bad. They also believe that if failure does occur, learning from it is pretty straightforward: simply ask people to reflect on what they did wrong and instruct them to avoid similar actions in the future. Or, better yet, assign a team to review what happened and develop a report to distribute. Unfortunately, these widely held beliefs are misguided. Here’s the simple truth about failure: it is sometimes bad, sometimes good, and often inevitable. Good, bad, inevitable—learning from organizational failures is anything but straightforward.

To learn from mistakes and missteps, organizations must employ new and better ways to go beyond lessons that are superficial (procedures weren’t followed) or self-serving (the market just wasn’t ready for our great new product). This requires jettisoning old cultural beliefs and stereotypical notions of success and replacing them with a new paradigm that recognizes that some failures are inevitable in today’s complex work organizations and that successful organizations will be those that catch, correct, and learn from failures quickly. This chapter examines the inevitability of failure while teaming and highlights the importance of learning from small, seemingly insignificant failures. It then explains the cognitive and social barriers to learning from failure and demonstrates how failures vary across the Process Knowledge Spectrum. Finally, the chapter closes by providing practical strategies for developing a learning approach to failure.

The Inevitability of Failure

Workplace failure is never fun. From the small disappointment (a suggestion falls flat in a meeting) to the large blunder (a design for a new product is rejected by a focus group after months of work), failure is emotionally unpleasant and can erode confidence.1 Even when engaged in a process explicitly designed to be trial-and-error, most of us would still prefer not to fail. But failure is a fact of life. There is no such thing as perfection, especially in teaming. When bringing together people with different perspectives and skills to collaborate, failure is inevitable for two primary reasons. First, there are the technical challenges. New equipment, technological advances, and process changes all contain unexpected features and require new knowledge and skills. That’s why individuals or groups faced with new or complex problems or procedures rarely get things right the first time.

The second reason that failures occur while teaming are the interpersonal challenges that people face. These challenges are less tangible than the technical puzzles, but are often far more difficult to understand and resolve.2 One person may fail to report crucial information, provoking resentment from others in the group. Another person may struggle with learning how to implement a new technology. A team of people who are unfamiliar with one another’s strengths and weaknesses may encounter flaws in how they interact. These flaws include assigning detail-oriented tasks to a person whose strength is working with the “big picture,” or scheduling a shift with two people who are inexperienced with a new procedure rather than pairing a less experienced team member with a more experienced mentor. These challenges are compounded by a tendency shared by many high achievers to think of colleagues as an audience—that is, as people who expect a great performance—rather than thinking of them as colearners and coworkers. Add up these interpersonal variables, and any new teaming effort will experience failures on a social level that might not arise in the same way in a bounded, long-term team. Of course, this doesn’t mean failures should be avoided. It means they need to be as small as possible and they must produce as much learning as possible.

The Importance of Small Failures

Large, well-publicized organizational failures make people sit up and take notice. But many of these “headline failures,” such as the Columbia and Challenger shuttle tragedies, the massive BP oil leak in the Gulf, and the U.S. Security and Exchange Commission’s failure to heed warnings about Bernard Madoff’s investment practices, represent disasters that were allowed to develop because small failures were ignored. Likewise, terrorist attacks can almost always be traced back to pieces of intelligence that have either been ignored or not communicated to appropriate agencies. Even less far reaching but still dramatic failures, such as the fatal drug error that killed a Boston Globe correspondent at Boston’s Dana Farber Hospital, occur after mistakes were missed, problems ignored, and warnings dismissed.3 Most large failures have multiple causes, and some of these causes are deeply embedded in organizations. These are rarely simple to correct. But the fact is, small failures are early warning signs that are vital to avoiding catastrophic failure in the future.4

An intelligent process of organizational learning from failure, whether in the hospital operating room or the executive boardroom, requires proactively identifying and learning from small failures. Small failures are often overlooked. Why? Because when they occur they appear to be minor mistakes or isolated anomalies hardly worth the time to contemplate. Small failures arise not only in the course of purposeful experimentation, but also when daily work is complex and interdependent. When problems inevitably arise during the course of business in these situations, workers have two choices: they can compensate for problems, which would likely make the small failure go unnoticed. But compensating for problems can be counterproductive if doing so isolates information and obscures the opportunity to learn. The other choice is they can seek to resolve the underlying cause of the small failure by notifying those who can help correct the problem. This, however, would expose poor performance. Due to a natural desire to protect their image or status, very few people would voluntarily choose to publicize their own mistakes. But to capture the value of small failures, individuals and groups must learn to acknowledge their performance gaps.

Although seemingly insignificant, small failures can offer opportunities for substantial organizational learning. Take radiologists’ mammogram readings. When Dr. Kim Adcock became chief of radiology at Kaiser Permanente in Colorado, there was an expected 10–15 percent error rate due to inherent difficulties in reading mammograms. Standard practice dictated that a failure to detect one, or even several tumors, did not reflect negatively on a radiologist’s ability. These missed tumors were considered small failures, and were therefore easily ignored. Adcock, however, sought a way to learn from these small failures. By analyzing the large data sets that accumulate after multiple mammogram readings, he found meaningful patterns and produced detailed feedback, including bar charts and graphs, for each individual radiologist that helped to proactively identify and avoid failure.5 For the first time, the doctors could learn whether they were falling near or outside of the acceptable range of errors, allowing them to improve their accuracy rates.

Organizations that make timely use of the seemingly small, but important, learning opportunities contained in failure are more able to improve, innovate, and prevent catastrophes than those who ignore or hide failures. If small failures are not widely identified, discussed, and analyzed, it’s very difficult for larger failures to be prevented.6 But knowing this fact doesn’t make it any easier to embrace and learn from failure. Regardless of intention or incentives, it’s still difficult to overcome the psychological, cognitive, and social barriers to admitting and analyzing failure.

Why It’s Difficult to Learn from Failure

Most of us have been primed to aim for success. We’ve been schooled from an early age to focus on good grades, regular promotions, performance awards. As a result, most of us see failure as unacceptable.7 We would just as soon avoid it altogether, even if we know that failure is inevitable and creates important learning opportunities. It’s hard to be the nurse who administers the wrong medication or the marketing executive who squanders a window of opportunity to launch a new product. And so, people at work often remain silent about the potentially informative mistakes, problems, or disappointments they’ve experienced, which means that companies miss the learning that could be gained from failures. This barrier to learning from failure is rooted in the strong psychological and social reactions that most people have to failing.8 Self-serving biases that bolster self-confidence and protect one’s public image make these barriers even stronger. And natural biases and their corresponding emotions are exacerbated by most organizations’ inclination to punish failure, as well as by the strong connection between the concepts of failure and fault.

Self-Esteem and Positive Illusions

Being held in high regard by other people, especially by one’s managers and peers at work, is a strong fundamental human desire.9 Most people believe that revealing failure will jeopardize this esteem. Even though people may intellectually appreciate the idea of learning from failure and are sympathetic to others’ disclosures of failure, they have a natural aversion to disclosing or even publicly acknowledging their own failures. People have an instinctive tendency to deny, distort, or ignore their own failures. The fundamental human desire to maintain high self-esteem is accompanied by a desire to believe that we have a reasonable amount of control over important personal and teaming outcomes. Psychologists argue that these desires give rise to “positive illusions,” which are unrealistically positive views of the self, accompanied by illusions of control that contribute to helping people be energetic and happy. Some even argue that positive illusions are a hallmark of mental health.10 However, the same positive illusions that boost our self-esteem and sense of control are at odds with an honest acknowledgment of failure.

The challenge isn’t just emotional. Human cognition introduces perceptual biases that reduce the accuracy of our causal attributions. Even without meaning to, all of us favor evidence that supports our existing beliefs rather than alternative explanations. Similarly, the psychological trap known as the fundamental attribution error—the tendency to ascribe personal rather than situational explanations for others’ shortcomings (discussed in Chapter Two) makes us less aware of our own responsibility for failures and very willing to blame others for the failures we observe. People tend to be more comfortable considering evidence that supports what they believe, denying responsibility for failures, and attributing problems to others. Understandably, these individual-level emotional and cognitive barriers have a dramatic affect on our ability to discuss failure effectively.

Failure Is Tough to Talk About

Even when failures are identified, social factors inhibit constructive discussion and analysis. Most managers lack the skills for handling the strong emotions that often surface in discussions that focus on mistakes and failure. This means that conversations attempting to unlock the potential learning from failure can easily degenerate into opportunities for scolding or finger-pointing. People experience negative emotions when examining their own failures, and this can chip away at self-confidence. Most people prefer to put past mistakes behind them rather than revisit them for greater understanding. In addition, most managers admire and are rewarded for efficiency and action, not for deep reflection and painstaking analysis.

But effective teaming requires its members to be comfortable in some uncomfortable situations like not being right, asking for help, or admitting mistakes. Analyzing and discussing failure requires openness, patience, and a tolerance for ambiguity. These behaviors must be embedded in the company culture. Consider the following example from Toyota Motor Company: James Wiseman was already a successful businessman by the time he joined Toyota in Georgetown, Kentucky, to manage its statewide public affairs program. Fujio Cho, later Chairman of Toyota worldwide, was then the head of the Georgetown factory. Wiseman recalled an important lesson about success and failure:

I started going in there and reporting some of my little successes. One Friday, I gave a report of an activity we’d be doing … and I spoke very positively about it. I bragged a little. After two or three minutes, I sat down. And Mr. Cho kind of looked at me. I could see he was puzzled. He said, “Jim-san. We all know you are a good manager, otherwise we would not have hired you. But please talk to us about your problems so we can work on them together.”11

Wiseman said that it was “like a lightning bolt. … Even with a project that had been a general success, we would always ask, ‘What didn’t go well, so we can make it better?’ ” Jim Wiseman later became Toyota’s Vice President of corporate affairs for manufacturing and engineering in North America, and Fujio Cho became the chairman of Toyota worldwide. At least part of their success had to do with their ability to ask and discuss that critical question: What didn’t go well so we can make it better? They were able to consistently reframe failure so that it was seen as a learning opportunity, rather than as an embarrassing event. More generally, they understood the need to create productive policies and norms for dealing with failure that helped overcome the organizational tendency to punish failure.

Organizations Punish Failure

You might think that those highest in organizational hierarchies would be confident enough to disclose failures. Surely an occasional slip-up is understandable given their overall track record, right? Wrong. Managers have an added incentive to disassociate themselves from failure because most organizations reward success and penalize failure. This means that holding an executive or leadership position in an organization doesn’t imply an ability to acknowledge one’s own failures. Dartmouth business professor Sydney Finkelstein’s in-depth investigation of major failures at over 50 companies suggested that the opposite might be the case: The more senior the manager, the greater the social and psychological penalty for being fallible.12 In his study, Finkelstein wrote:

Ironically enough the higher people are in the management hierarchy, the more they tend to supplement their perfectionism with blanket excuses, with CEOs usually being the worst of all. For example, in one organization we studied, the CEO spent the entire forty-five-minute interview explaining all the reasons why others were to blame for the calamity that hit his company. Regulators, customers, the government, and even other executives within the firm—all were responsible. No mention was made, however, of personal culpability.13

Organizational structures, policies and procedures, and senior management behavior can discourage people from analyzing failures and embracing experimentation.14 A natural consequence of punishing failures is that employees learn to avoid identifying them, let alone analyzing them or experimenting if the outcome is uncertain. Even in more tolerant organizations, most managers fail to reward these behaviors through raises or promotions, and instead rely on punitive actions that often reflect a misunderstanding of the relationship between failure and fault.

The Blame Game

Failure and fault are inseparable in most cultures. Every child learns at some point that admitting failure means taking the blame for a disappointment or breakdown. And yet, the more complex the situation in which we find ourselves, the less likely we will be to understand the relationship between failure and fault. Executives I’ve interviewed in organizations as different as hospitals and investment banks admit to being perplexed about how to respond constructively to failure. If people aren’t blamed for failures, their reasoning goes, what will ensure that they do their best? This concern is based on a false dichotomy. In actuality, a climate for admitting failure can coexist with high standards for performance.

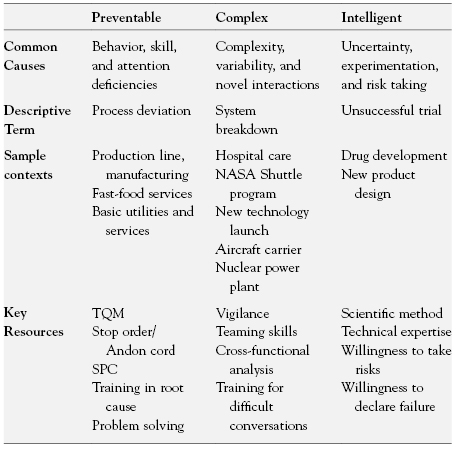

To understand why this dichotomy exists and how leaders often misperceive the relationship between failure and fault, consider Figure 5.1. Listing nine possible reasons for failure, the figure represents the range and diversity of causes identified in research on organizational failure.

Figure 5.1. A Spectrum of Reasons for Failure

Source: Edmondson, A. C. “Strategies for Learning from Failure,” Harvard Business Review 89, no. 4 (2011). Reprinted with permissions from Harvard Business Review.

Which of these nine causes involve blameworthy actions? People may disagree at the margins, but most will draw the line either before or after cause number two. In other words, most people agree that deliberate deviance—intentionally violating a rule or a procedure—warrants blame. But inattention, next on the list, may or may not deserve condemnation. If created by a lack of employee effort, then perhaps inattention is blameworthy. If created instead by a physiological limitation due to an overlong shift, inattention can be blamed on the manager who assigned the shift, not on the employee whose attention wandered. As we go down the list, it becomes more and more difficult to find blameworthy acts. In fact, failures that occur as a result of thoughtful experimentation can even be recognized as praiseworthy acts that generate valuable information. Accordingly, the list presents a spectrum that goes from obvious blame to obvious praise.

When I ask executives to consider this kind of causal spectrum and then estimate what percentage of the failures in their organizations are caused by blameworthy events, the answers usually come back between 2 and 5 percent. But when I then ask what percentage of failures are treated as if caused by blameworthy events, after a pause or laugh, their responses often yield a much higher number in the 70–90 percent range.15

The difference between failures that are truly blameworthy and those that are simply treated as blameworthy reveals a gap between logic and practice. Logically, we can see that many of the things that go wrong in organizations couldn’t have been prevented, or may come from thoughtful exploration of a new area. But emotionally, failure is unpleasant regardless of the reason or circumstance. This unpleasantness helps explain the punitive connection between fault and failure even when the failure is fault-free. The unfortunate consequence of this gap between logic and practice is that many failures go unreported or misdiagnosed and their lessons are lost. As the next section explains, the importance, costs, and ramifications of these failures differs greatly across the Process Knowledge Spectrum.

Failure Across the Process Knowledge Spectrum

The role failure plays in a teaming effort or within a learning organization varies in important ways across the Process Knowledge Spectrum. Although a 90 percent failure rate might be expected in a biology research lab, if 90 percent of the food Taco Bell served was wrongly prepared or used spoiled ingredients, obviously that would be unacceptable. Likewise, if 70 percent of commercial airline flights never made it to their destination or 50 percent of new automobiles broke down as they were driven off the dealer’s lot, consumers would be incensed. If even a 1 percent failure rate occurred in any of these three settings, the offending companies would soon be out of business. Clearly, the frequency and the meaning of failure shifts as we move across the Process Knowledge Spectrum. The following sections outline critical distinctions between how failure should be viewed in routine, complex, and innovation operations.

Failure in Routine Operations

Even in routine tasks, small mistakes and failures happen because people are fallible. These failures are usually caused by small process deviations and generally involve reasons one through three (deviance, inattention, and inability) in the previous list of nine possible causes of failure. Most of these mistakes can be quickly corrected and the work goes on. But some small failures in routine processes provide valuable information about improvement opportunities for enhancing quality or efficiency. The key for learning from failure in routine operations, such as assembly plants, call centers, and fast-food restaurants, is to establish and maintain an organizational system that enables people to find, report, and correct errors.

The quintessential routine process is the automotive assembly line, and no system for managing a routine process surpasses the Toyota Production System (TPS) in learning from failures. TPS builds continuous learning from tiny failures and small process deviations into its systematic approach to improvement. When team members on the assembly line at Toyota spot a problem on any vehicle, or even a potential problem, they are encouraged to pull a rope called the Andon Cord to initiate a rapid diagnostic and problem-solving process. Production continues unimpeded if the problem is solved in less than a minute. Otherwise, production is halted despite the substantial loss of revenues until the failure is understood and resolved.

Failure in Complex Operations

Failures in complex operations, which require the work to be tailored to a specific customer or patient and in which multiple interacting processes create uncertainty, are particularly challenging because the stakes tend to be high. Such failures are usually due to faulty processes or system breakdowns. This means that most failures occur due to reasons in the middle of the previous causal spectrum (process inadequacy, task challenge, and process complexity). Not surprisingly, analysis usually reveals an organization’s process, rather than a human, to be at fault when disaster strikes.

Important failures in complex operations are usually the result of an unfortunate combination of many small failures. James Reason, an error expert, uses Swiss cheese as a metaphor to explain how failures occur in these settings. Failures occur when multiple events accidentally line up, like holes in Swiss cheese, forming an unexpected tunnel that allows a number of separate failures to pass through without correction. Therefore, the risks inherent in complex systems call for extraordinary vigilance to help organizations detect and respond to the inevitable small failures, in order to avoid the large, consequential ones.

Because many complex organizations, such as nuclear power plants, air traffic control facilities, and aircraft carriers, present extremely high levels of risk, it would be wrong to say that failures are encouraged or rewarded. But, as previously mentioned, failures are inevitable. Recognizing this fundamental tension, some scholars have studied how high-risk organizations are able to operate safely in a remarkably consistent way and earn the designation High Reliability Organizations (HROs).16 These organizations are resilient, able to adjust on the fly, and bounce back under challenging conditions.17 Rather than trying to prevent all errors, HROs devise ways to contain and cope with errors as they occur, minimizing their effects before they escalate. Termed “heedful interrelating” by University of Michigan professor Karl Weick, this unusual level of vigilance includes the ability to detect and recover from small failures before real harm occurs.18 Facing the potential for larger failure when smaller failures interact, leaders in complex organizations must promote resiliency by acknowledging that failure is inevitable, making it psychologically safe to report and discuss problems, and promoting habits of vigilance that support rapid detection and responsiveness.

Failure in Innovation Operations

Where knowledge is less well developed, it stands to reason that failures are more likely. Indeed, as we move to the right on the Process Knowledge Spectrum, failure is not only expected, it is essential to progress. To innovate, people must test ideas without knowing in advance what will work. Therefore, failures in innovation operations are usually due to reasons seven through nine on the causal spectrum presented in Figure 5.1 (uncertainty, hypothesis testing, and exploratory testing).

Researchers in basic science, tireless laboratory experimenters who have discovered such advances as human genome sequencing or the latest insights into galactic dust, know that the experiments they conduct, often for decades, will have a high failure rate, alongside the occasional spectacular success. Scientists in some fields confront failure rates that are 70 percent or higher. All pharmaceutical companies have had to learn from failure to succeed. The daunting reality is that over 90 percent of newly developed drugs fail in the experimental stage and never make it to market.

In innovation operations, the keys to success are thinking big, taking risks, and experimenting, while remaining fully aware that failure and dead ends are inevitable on the road to innovation. Award-winning design firm IDEO employs the slogan: “Fail often in order to succeed sooner.”19 This simple motto reveals an attitude that has given rise to products that appear in ISDA and BusinessWeek magazine’s IDEA awards and regularly ranks them in the Fast Company 50, a list of the world’s most innovative companies. Teams at IDEO truly believe that success comes more quickly when they fail early and often, so long as they learn the lessons each failure has to offer.

Sometimes learning from failure in innovation operations means further investigation and analysis to ascertain if a failed product or design may prove to have a viable alternate use. Pfizer’s lucrative Viagra was originally designed to be a treatment for angina, a painful heart condition. Eli Lilly discovered that a failed contraceptive drug could treat osteoporosis and consequently developed the billion-dollar-a-year drug Evista.20 Strattera, a failed antidepressant, was discovered to be an effective treatment for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clearly, a one-size-fits-all-failures approach is too rigid for today’s complex organizations and markets. This means an important aspect of developing a learning approach to failure includes understanding how to match failure to both its cause and context.

Matching Failure Cause and Context

I have found that managers rarely understand or appreciate the need for context-specific approaches to failure. As a result, it’s common for them to apply an approach to failure that’s appropriate for one context (for example, routine operations where failures should be prevented) to another context where it’s inappropriate (for example, innovation operations where failures are valuable sources of new information). Take, for example, statistical process control (SPC), which uses statistical analysis of data to assess unwarranted variance from specified processes. SPC works well for identifying deviations from otherwise routine and visible patterns, but falters when used to catch and correct an invisible glitch like a poor clinical decision in the emergency room. As obvious as this example may seem, organizations make such errors all the time.

One well-meaning executive seeking to increase research productivity at Wyeth implemented financial incentives to reward scientists for steering more new compounds into the pipeline. Sure enough, more compounds went in. But, much to everyone’s disappointment, more viable drug candidates didn’t come out the other end. His strategy was a mismatch between the uncertainty of scientific research and the counting mindset that works well in ensuring process control in routine operations. A better approach would be to build a culture that rewards experimentation and early detection of failure.

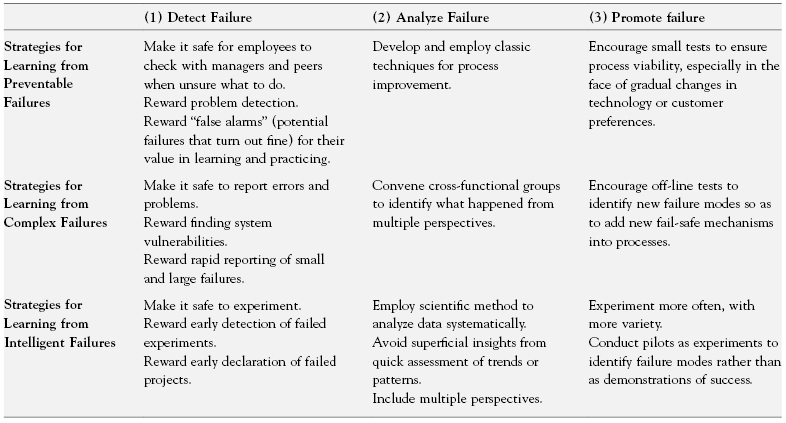

Determining the correct strategy for learning from a failure depends on the failure’s causes and context, which often go hand in hand. The word failure is terribly imprecise. This imprecision and ambiguity contributes to misdiagnosis of many failures. Although there are an infinite number of potential things that can go wrong in organizations, failures can be grouped into the three broad categories summarized in Exhibit 5.1.

- Preventable failures: process deviations in well-understood domains, usually caused by behavior, skill, or support deficits.

- Complex failures: process or system breakdowns that arise due to inherent uncertainty and may or may not be identified in time to prevent consequential accidents.

- Intelligent failures: the unsuccessful trials that occur as part of thoughtful experiments and provide valuable new information or data.

Not surprisingly, these three types of failures generally correspond with the three different Process Knowledge Spectrum categories: preventable failures with routine operations, complex failures with complex operations, and intelligent failures with innovation operations. As organizations have become more complex in today’s knowledge-based economy, however, this is not always true. Many times the boundaries between processes and problems become blurred. Take, for example, a software glitch that negatively affects a manufacturing production line. The manufacturing process may be a routine operation, but the software issue is most like a system breakdown that represents a complex failure. The overview presented in Table 5.1 reveals that each of the three types of failure has its own causes, context, and solutions.

Table 5.1: Organizational Failure Types

Preventable Failures

Behavior, skill, or support deficits in predictable operations constitute preventable failures. Most failures in this category can be considered “bad.” In high-volume, routine operations, well-specified processes, with proper training and support, can and should be followed consistently. When there are failures, gaps in skill, motivation, or supervision are likely the reason. These causes can be readily identified and solutions developed. In these instances, leaders should diagnose why their predictable operations are not performing well and design ways to motivate employees to get the job done correctly every time, or fix faulty processes.

Complex Failures

A large and growing number of organizational failures are the result of system complexity. When novel combinations of events and actions are to be expected, some necessarily give rise to failures. Such failures are not preventable in a conventional sense. Instead, they arise due to the inherent uncertainty of work in complex systems, where a particular combination of needs, people, and problems may have never previously occurred. Sample contexts include managing a global supply chain, responding to enemy actions on the battlefield, or running a fast-growing start-up. Though serious failures may be avoided by following safety and risk-management best practices, small process failures will occur. To consider these inevitable small failures “bad” not only indicates a lack of understanding of how complex systems work; it’s also counterproductive. Doing so blocks the rapid identification through which small failures are corrected and major failures are avoided.

Intelligent Failures

These types of failures generally occur in frontier or cutting-edge endeavors where experimentation is required to learn and succeed. Failures in this category shouldn’t be called “bad.” In truth, these types of failures can rightly be considered “good” because they provide valuable data that can help an organization leap ahead of the competition. Intelligent failures are essential in developing new knowledge. In innovation operations, the right kind of experimentation strategy helps to ensure the future growth of the company. Managers who operate on the assumption that change is constant and novelty is everywhere are more likely to get the most out of the failures that invariably will occur. In addition, they’re more apt to avoid the unintelligent failure of conducting experiments at a larger scale than is necessary. Plainly, when mistakes are inevitable and innovation is crucial, developing an environment that encourages learning from failure is an organizational imperative. Even with the best of intentions, however, such learning is hard to do.

Developing a Learning Approach to Failure

Because psychological and organizational factors inhibit both failure identification and analysis, a fundamental reorientation is needed to successfully learn from failure. Individuals and groups must be motivated to embrace the difficult and often emotionally challenging lessons that failures reveal. Doing so requires a spirit of curiosity and openness, as well as exceptional patience and a tolerance for ambiguity. These traits and behaviors are best characterized by what, in the management literature, has been termed an inquiry orientation. This type of orientation is presented as a contrast to an advocacy orientation. Both terms describe contrasting communication behaviors and distinct approaches to group decision making.

Advocacy and Inquiry Orientations

As discussed earlier in the chapter, organizational structures and processes can hinder the ability of a group to learn from failure. In groups characterized by an advocacy orientation, these structures and processes support a top-down management approach and the organizational status quo. Therefore, when trying to incorporate the unique knowledge of different members, the unintentional results often include antagonism, a lack of listening and learning, and limited psychological safety for challenging authority. Recall the story of the Columbia space shuttle disaster at the beginning of Chapter Four. Thoughtful inquiry could have generated new insights about the threat posed by the foam strike that ultimately lead to the death of seven astronauts. Instead, NASA’s rigid hierarchy, strict rules, and reliance on quantitative analysis discouraged novel lines of inquiry that may have helped prevent the disaster.

In contrast, an inquiry orientation is characterized by the perception among group members that multiple alternatives exist and that frequent dissent is necessary. These perceptions result in a deeper understanding of issues, the development of new possibilities, and an awareness of others’ reasoning. This orientation can counteract common group tensions and process failures. Learning about the perspectives, ideas, and experiences of others when facing uncertainty and high-stakes decisions is critical to making appropriate choices and finding solutions to novel problems. But how can leaders promote an inquiry orientation to facilitate learning? The terms exploratory response and confirmatory response have recently been used to describe distinct ways that leaders can orient individuals and groups to respond to potential failures.21

Confirmatory and Exploratory Responses

Leaders play an important role in determining a group’s orientation to a perceived failure. Facing small or ambiguous problems, leaders can respond in one of two basic ways: confirmatory or exploratory responses. A confirmatory response by leaders reinforces accepted assumptions, naturally triggering an advocacy orientation. When individuals seek information in this mode, they look for data that confirms existing beliefs, which is a natural human response. Leaders encourage or reinforce a confirmatory response, when they act in ways consistent with established frames and beliefs. This often means they’re passive or reactionary rather than active and forward-looking.

In uncertain, risky, or novel situations, an exploratory response is more appropriate. Rather than supporting existing assumptions, an exploratory response requires a deliberate shift in the mindset of a leader. This alters the way a leader interprets and diagnoses the situation at hand. This shift involves challenging and testing existing assumptions and experimenting with new behaviors and possibilities. When leaders adopt an exploratory approach, they embrace ambiguity and openly acknowledge gaps in knowledge. They recognize that their current understanding may require revision, and so they actively search for evidence in support of alternative hypotheses. Rather than seeking to prove what they already believe, exploratory leadership encourages inquiry and experimentation. This deliberate response helps to accelerate learning through proactive information gathering and simple, rapid experimentation.

It would be nice if transforming an organization into a learning enterprise was just a matter of altering the orientation and perspective of a single leader. But of course it’s not that simple. A productive approach to failure requires leadership, exercised by many individuals, to cultivate diagnostic acumen. In this way, an organizational culture of curiosity and analysis can be developed and nurtured. This helps people to develop a clearheaded understanding of what happened, rather than just “who did it” when something goes wrong. Doing this well means insisting on consistent reporting of failures, encouraging deep and systematic analysis, and promoting the proactive search for opportunities to experiment.

Strategies for Learning from Failures

Failure tolerance is a smart strategy for any organization wishing to gain new knowledge. Because organizations are more and more likely to encompass complex work and face unpredictable environments, a growing number of failures are of the complex type, and it’s crucial to anticipate and respond to them quickly. Moreover, great strategic advantage can be gained from intelligent failures. But neither type of failure can be put to good use without a rational approach to diagnosis and discussion. Given that failure is inherently emotionally charged, responding to it requires specific, purposeful strategies. Three activities—detection, analysis, and experimentation—are critical to learning from failures. As Table 5.2 shows, these three activities apply to all types of failures, although how they’re carried out varies in important ways.

Table 5.2: Strategies for Learning from Failure

Failure Detection: Support Systems for Identifying Failure

The first crucial strategy to master is the proactive and timely identification of failure. This is especially true of the type of small and seemingly inconsequential failures that lead to large, often catastrophic, failures. Any organization can detect big, expensive failures. It’s the little ones that often go unnoticed. In many organizations, any failure that can be hidden is hidden, so long as it’s unlikely to cause immediate or obvious harm. Even more common is the tendency to withhold bad news related to pending failures as long as humanly possible.

Recognizing this, Allan Mulally, soon after being hired as CEO of Ford Motors, created a new system for identifying failures. Understanding how difficult it is for early-stage failures to make it up the corporate hierarchy, he asked his managers to color code their reports: green for good, yellow for caution, red for problems. Mulally was frustrated when, during the first couple of meetings, managers coded most of their operations green. He reminded managers how much money the company had recently lost and asked pointedly whether everything was indeed going along well. It took this prodding for someone speak up, tentatively offering a first yellow report. After a moment of shocked silence in the group Mulally clapped, and the tension was broken. After that, yellow and red reports came in regularly.22

Ford’s is not an isolated story. In companies around the world, even the most senior executives can be reluctant to convey bad news to bosses and colleagues. Shooting the messenger remains an enduring and problematic phenomenon, so it’s essential for leaders to proactively create conditions in which messages of failure travel up and across an organizational hierarchy. To do this, leaders need to engage in three essential activities: embrace the messenger, gather data and solicit feedback, and reward failure detection.

Embrace the Messenger.

Savvy managers understand the risks of unbridled toughness. An overly punitive response to an employee mistake may be more effective in stifling information about problems than in making your organization better. This is obviously not a good result. Managers’ ability to quickly diagnose and resolve problems depends upon their ability to learn about them. Organizations with a habit of punishing mistakes or errors will discourage this process. This means that psychological safety, as explained in Chapter Four, is the bedrock of any genuine failure identification and analysis effort.

Gather Data and Solicit Feedback.

My research has found that a lack of access to data on failures is the most important barrier to managers learning from them. This is especially true for preventable and complex failures. In these circumstances, people often believe that no failures are acceptable, so hiding them can seem the only feasible approach. That inaccessibility can be due as much to human resistance to identifying failure as to technical difficulties in understanding small mistakes. To overcome this barrier, organizational leaders must develop systems, procedures, and cultures that proactively identify failure.

Soliciting feedback is an effective way of gathering data and surfacing many types of failures. Feedback from customers, employees, and other sources can expose failures such as communication breakdowns, the inability to meet goals, or a lack of customer satisfaction. Proactively seeking feedback from customers often helps manufacturers and service providers identify and address failures in a timely manner. If you believe identifying customer dissatisfaction is a luxury, bear in mind that only 5–10 percent of dissatisfied customers choose to complain following a service failure. Instead, most simply switch providers.23 This means that if service companies fail to learn from their failures, they’re guaranteed to lose customers.

Reward Failure Detection.

Failures must be exposed as early as possible to allow learning in an efficient and cost-effective way. This requires a proactive effort on the part of managers to surface available data on failures and use it in a way that promotes learning. The detection challenge for intelligent failures lies in knowing when to declare defeat in an experimental course of action. The human tendency to hope for the best impedes early failure identification and is often exacerbated by strict organizational hierarchies. As a result, fruitless research projects are frequently kept going much longer than is scientifically rational or economically prudent. We throw good money after bad, hoping to pull a rabbit out of a hat. In innovation operations, this happens more often than most managers realize. Engineers’ or scientists’ intuition can be telling them for weeks that a project has fatal flaws, but making the formal decision to call it a failure may be delayed for months. Considerable resources are saved when such projects are stopped in a timely way and people are freed up to explore the next potential innovation.

Failure Analysis: Support Systems for Analyzing and Discussing Failure

Once organizations detect problems, they must use discipline and sophisticated analytic techniques to delve deeper than the obvious, superficial causes of failure, to go beyond quick fixes, and to learn the right lessons and implement the best remedies. After detection, failure analysis is one of the most overlooked activities in organizations today. This is true even though discussing failures has many important organizational benefits. By discussing failures, the valuable learning that might result from analyzing simple mistakes won’t be overlooked. Discussion also provides an opportunity for other group members or employees who may not have been directly involved in the failure to learn from it, too. These employees can then bring new perspectives and insights that deepen the analysis and help to counteract self-serving biases that may color the perceptions of those most directly involved in the failure. The U.S. Army conducts After Action Reviews that enable participants to analyze, discuss, and learn from both the successes and failures of a variety of military initiatives.24 Similarly, hospitals use Morbidity and Mortality (M&M) conferences in which physicians convene in brutally candid sessions to discuss significant mistakes or unexpected deaths.

The primary danger in failure analysis is that people tend to leap prematurely to conclusions, unless the analysis emphasizes a careful consideration of all possible causes and effects. For example, a retail bank that was losing customers conducted a failure analysis to figure out why customers were switching to other banks. The data showed that most customers who closed their accounts picked “interest rates” as the reason for switching banks. However, once the bank actually compared their interest rates to others in the area they found no significant differences. Might the customers’ real reasons for leaving be something different from what they actually said? Careful interviews with the dissatisfied customers revealed a less obvious reason for customer defections: they were irritated by being aggressively solicited for a bank-provided credit card, and then subsequently turned down for the card. The deeper failure analysis concluded that the problem lay in the bank’s marketing department. Consequently, changes were made so the marketing department could do a better job of screening candidates for bank-provided credit cards.25

This type of rigorous analysis, however, requires that people put aside their resistance to exploring unpleasant truths and instead take personal responsibility. Analysis can only be effective if people speak up openly about what they know and if other members of the organization listen. To develop an environment that overcomes organizational and social barriers to failure analysis, leaders should take actions such as implementing systems for total quality management (especially in routine operations), convene interdisciplinary groups to look for potential vulnerabilities (especially in complex operations), and take a systematic approach to experimenting and analyzing data (especially in innovation operations).

Develop and Employ Systems for Total Quality Management.

Preventable failure analysis is best accomplished through the classic techniques of process improvement such as total quality management (TQM), with its discipline of root-cause problem solving. The major management challenge lies in motivating people to keep going beyond first-order observations (procedures weren’t followed) to second- and third-order diagnoses about why the failure occurred and what underlying conditions contributed to the problem. Process improvement techniques like TQM work best in routine operations, because high-volume activities allow large amounts of data on process and performance to be collected and analyzed with statistical methods. These analyses reveal process deviations (problems) that might otherwise go undetected, and thereby point to improvement opportunities. In the absence of the repetitive processes characteristic of routine operations, TQM and statistical analyses are less useful in learning from failure, and so alternative techniques for systematic analysis are presented.

Convene Interdisciplinary Groups.

Formal processes or forums for discussing, analyzing, and applying the lessons of failure are needed to ensure that effective learning occurs. Learning from complex failures requires the use of interdisciplinary teams with the diverse skills and perspectives necessary for both anticipating and analyzing complex incidents. Multidisciplinary groups are able to combine their areas of expertise to identify potential vulnerabilities in complex systems. They can discuss how processes work from different perspectives and recognize the potential for things to go wrong. They also can work together to figure out the causes of failures that do occur. Such groups are most effective when people have technical skills, expertise in analyzing data, and diverse perspectives, allowing them to explore different interpretations of a failure’s causes and consequences. Diverse perspectives are essential because most failures have multiple contributing factors related to different departments or requiring different areas of expertise to understand them. Because this process usually has the potential for creating conflict, expert facilitators skilled in interpersonal or group process can help keep the process productive.

Analyze Data Systematically.

The intellectual challenge of analysis intensifies as we move from preventable to complex to intelligent failures. As noted, statistical data analysis is a useful tool for analyzing large amounts of qualitative data—for example, the weight or dimensions of batteries in a production run—to assess consistency. Statistical analysis prevents mistaking what’s called normal variation for problematic variation. It helps separate signal from noise. Complex and intelligent failures instead require deep qualitative analysis, to identify what happened and why, and to brainstorm the implications of these conclusions. Complex and intelligent failures are often unique, unprecedented events. Complex failures occur when multiple factors come together in new ways and give rise to a system breakdown. Analysis thus involves figuring out all the possible contributors to the failure—a creative task that benefits immensely from the involvement of a motivated team. Intelligent failures also must be analyzed systematically, so as to avoid drawing the wrong conclusions from the failure. For example, when a new experimental chemotherapy drug developed at Eli Lilly failed in clinical trials, the doctor conducting the trials analyzed the failure systematically—rather than assuming the drug simply didn’t work—and discovered something important. Patients who didn’t do well with the drug had a folic acid deficiency. Sure enough, further study showed that giving patients folic acid along with the drug solved the problem, thereby rescuing a drug that the organization had been ready to discard.26

Failure Production: Establish and Support Systems for Deliberate Experimentation

The third critical, and possibly most provocative, action a leader can take in establishing a culture conducive to learning from failure is to strategically produce failures for the express purpose of learning and innovating. For scientists and researchers, failure is not optional; it’s part of being at the forefront of scientific discovery. They know that each failure conveys valuable information, which they’re eager to obtain more quickly than the competition. Exceptional organizations, therefore, go beyond detecting and analyzing problems by intentionally generating intelligent failures that increase knowledge and suggest alternative courses of action.

It’s not that managers in these organizations enjoy failure. They don’t. But they recognize that failure is a necessary by-product of experimentation. Thus, these organizations devote some portion of their energy to experimentation in order to find out what works and what doesn’t. Despite the increased rate of failure that accompanies deliberate experimentation, organizations that experiment effectively are likely to be more innovative, productive, and successful than those that don’t take such risks.27 Devoting resources to experimentation doesn’t have to mean dramatic experiments with large budgets. In one study, for example, I found that hospital care improvement teams devised solutions to improving such mundane activities as clinician hand-washing behavior by experimenting with different persuasion techniques.28

On a larger scale, Google institutionalized 20 Percent Time, which is a portion of paid employee time allotted to independent projects. Although the projects must be officially approved by a supervisor, employees have come to expect that most proposals will be given the go-ahead. Although the real or immediate work takes precedence, employees are encouraged to devote one day a week to these exploratory projects, in the hopes that they lead to the next big innovation. Although 20 Percent Time is universally lauded for the invention of such lucrative breakthroughs as Gmail and Adsense, what’s not usually mentioned is how many of these independent projects fail. Companies like Google that are known for innovation understand that for one successful new product or service, there are usually countless well-intentioned failures.

Leaders can sanction and even institutionalize deliberate experimentation. Unfortunately, this is both technically and socially challenging to implement intelligently. Purposefully setting out to experiment and generate both failures and successes is particularly difficult when failures are stigmatized. Conducting experiments requires acknowledging that the status quo is imperfect and could benefit from change. One of the advantages of most forms of experimentation is that failures can often take place off-line in simulations and pilots. However, even in these situations, the fear of stigma or embarrassment can still make people reluctant to take risks. Therefore, strong leadership is needed to encourage people to engage wholeheartedly in experimentation. This type of leadership includes rewarding both experimentation and failure, understanding the power of words, and designing intelligent experiments that increase knowledge and ensure learning.

Reward Experimentation and Its Inevitable Failures.

Experimentation is difficult when organizations emphasize and reward only success. Research in social psychology has demonstrated that espoused goals of increasing innovation through experimentation are not as effective when rewards penalize failures as when rewards are aligned with the goal of promoting experimentation.29 In addition, explicit messages that both recognize the inevitability and value of failures can counteract the corporate stigma otherwise associated with failure. To help reduce this stigma and encourage timely declaration of failure, the chief scientific officer at Eli Lilly introduced “failure parties” to honor intelligent, high-quality scientific experiments that failed to achieve the desired results. Redeploying valuable resources, particularly scientists’ time, to new projects earlier rather than later can save hundreds of thousands of dollars. Rewarding failure is tricky. Many managers worry about creating a permissive, anything-goes atmosphere, imagining that people will start to believe failure is just as good as success. In reality, however, most people are highly motivated to succeed, based on the natural desire to do well and to be recognized for their competence. They are less motivated, however, for the reasons discussed in this chapter, to reveal and analyze failure, and so it takes leadership encouragement to make it happen. It is not a matter of formal metrics and cash rewards, but rather informal acknowledgment and celebration of the lessons learned from failure.

Words Matter.

One way to counteract failure’s stigma and promote increased experimentation is through the use of more precise terminology. This simple truth is recognized in the notion of trial and error, a discovery strategy for finding out what works when little is known. Strictly speaking, the phrase trial and error is a misnomer. Instead, “trial and failure” is more appropriate. Error implies that you could have done it right, and not doing so constitutes a mistake. But a trial is needed when results are not knowable in advance.

Why does it matter if managers treat a trial’s unfavorable outcomes as errors rather than as failures? Errors are preventable deviations from known processes. Failures include both the preventable (errors) and the unpreventable. Just as many hospitals have learned to call certain adverse medical events “system breakdowns” rather than clinician errors, leaders can call experiments that fail “unsuccessful trials.” The difference both cognitively and emotionally between these terms is palpable. Such small changes in language can have a major impact on organizational culture and counterbalance the well-established psychological barriers to learning from failure.

Design Intelligent Failures for Learning.

When learning from failure is taken seriously, experiments, simulations, and pilot programs are planned and executed in a way that stretches current knowledge and capacities. Designing these types of experiments for learning means testing limits and pushing the boundaries of what works. Therefore, successful experiments are often those that are designed to fail.

In my research, however, I’ve found that far too many experiments are designed to endorse or confirm the likelihood of success. Consider the way in which many pilot programs—a common example of experimentation in business—are devised and implemented. In their hunger for success, many managers in charge of piloting a new product or service typically do whatever they can to make sure it’s perfect right from the beginning. Paradoxically, this tendency to make sure a pilot is wildly successful can inhibit the more important success of the subsequent full-scale launch. Pilots should instead be used as tools to learn as much as possible about how a new service performs well before allowing shortcomings to be revealed by a full-scale launch. However, when managers of pilots work to make sure they succeed, they tend to create optimal conditions rather than representative or typical ones. Exhibit 5.2 offers six useful questions to help leaders design pilots that increase the probability of producing intelligent failures that generate valuable information.

- Is the pilot program being tested under typical circumstances instead of optimal conditions?

- Are the employees, customers, and resources representative of the firm’s real operating environment?

- Is the goal of the pilot to learn as much as possible, rather than to demonstrate to senior managers the value of the new system?

- Is the goal of learning as much as possible understood by everyone involved, including employees and managers?

- Is it clear that compensation and performance ratings are not based on a successful outcome of the pilot?

- Were explicit changes made as a result of the pilot program?

Source: Edmondson, A. C. “Strategies for Learning from Failure,” Harvard Business Review 89, no. 4 (2011). Reprinted with permissions from Harvard Business Review.

As the questions demonstrate, managers hoping to successfully launch a new, innovative product or service shouldn’t try to produce success the first time around. Instead, they should attempt to engage in the most informative trial-and-failure process possible. A truly successful pilot is designed to discover everything that could go wrong, rather than proving that under ideal conditions everything can go right. This strategy for learning from pilot-size failures is a way to help ensure that full-scale, online services succeed. And, as a result, it is also the very essence of how organizations master the art of learning from failure.

Leadership Summary

Teaming brings the occasional failure. This creates an imperative for organizations to master the ability to learn from failure. Yet few organizations have a well-developed capacity to dig deeply enough to understand and capture the potential lessons that failures offer. Research demonstrates that this gap can’t be explained by a lack of commitment to learning. Instead, the processes and incentives necessary to identify and analyze failure are lacking in most organizations. Add the human desire to avoid the unpleasantness and loss of confidence associated with acknowledging failure, and it’s easy to understand why so few organizations have made the shift from a culture of blame to a culture in which the rewards of learning from failure can be fully realized.

This is regrettable for a number of reasons. Many failures provide valuable information about improvement opportunities for enhancing quality or efficiency. In addition, organizations that pay more attention to small problems are more likely to avert large or catastrophic failures. Most important, however, organizations that embrace failure are likely to learn and innovate faster than their competition. An environment that supports failure identification and analysis encourages the type of purposeful experimentation essential to progress. These types of experiments, and the intelligent failures they produce, increase knowledge and help to ensure that new products and services succeed.

Creating an environment in which people have an incentive to reveal and discuss failure is the job of leadership. This means executives and managers must resolve not to indulge in the natural tendency to express strong disapproval of what may at first appear to be incompetence. Instead, by providing appropriate rewards and using language that helps destigmatize failure, leaders can create a culture conducive to inquiry, discovery, reflection, and experimentation. To understand what went wrong and how to prevent it in the future, learning from failure often requires working with people from different groups, specialties, or even regions. The next chapter will examine the specific challenges of teaming across these types of boundaries and how to manage cultural and occupational differences.

LESSONS AND ACTIONS

- When bringing together people with different perspectives and skills, failure is inevitable because of both technical and interpersonal challenges.

- Failures provide valuable information that allows organizations to be more productive, innovative, and successful. But due to strong psychological and social reactions to failing, most of us see failure as unacceptable.

- Logically, we can see that many failures in organizations cannot be prevented, but emotionally, it’s hard to separate failure from blame. This leads to the types of punitive reactions that cause many failures to go unreported or misdiagnosed.

- The causes of failure vary across the Process Knowledge Spectrum. In routine operations, failures are usually caused by small process deviations. Failures in complex operations are usually due to faulty processes or system breakdowns. In innovation operations, failures are usually due to uncertainty and experimentation.

- Although there are an infinite number of things that can potentially go wrong in organizations, failures can be grouped into three broad categories: preventable failures, complex failures, and intelligent failures.

- Leaders looking to develop a learning approach to failure should adopt an inquiry orientation that reflects curiosity, patience, and a tolerance for ambiguity. Doing so makes it safe to talk about failures and reinforces norms of openness.

- Failure detection, failure analysis, and purposeful experimentation are critical to learning from failures.

- To encourage failure detection, leaders need to embrace the messenger, gather data and solicit feedback, and reward failure detection.

- To support failure analysis, leaders should convene interdisciplinary groups and take a systematic approach to analyzing data.

- To promote purposeful experimentation, leaders must reward both experimentation and failure, use terminology that counteracts psychological barriers to learning from failure, and design intelligent experiments that generate more smart failures.

Notes

1. M. D. Cannon and A. C. Edmondson, “Confronting Failure: Antecedents and Consequences of Shared Beliefs About Failure in Organizational Work Groups,” Journal of Organizational Behavior 22 (2001): 161–177; A. C. Edmondson and M. D. Cannon, “Failing to Learn and Learning to Fail (Intelligently): How Great Organizations Put Failure to Work to Innovate and Improve,” Long Range Planning Journal 38, no. 3 (2005): 299–319.

2. Ibid. (Cannon and Edmondson; Edmondson and Cannon)

3. R. M. J. Bohmer and A. Winslow, “Dana-Farber Cancer Institute,” HBS Case No. 669–025 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 1999).

4. A. C. Edmondson, E. Ferlins, F. Feldman, and R. Bohmer, “The Recovery Window: Organizational Learning Following Ambiguous Threats,” in Organization at the Limit: Lessons from the Columbia Disaster, ed. M. Farjoun and W. Starbuck (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2005).

5. M. Moss, “Spotting Breast Cancer, Doctors Are Weak Link,” New York Times, June 27, 2002, late ed., A1; M. Moss, “Mammogram Team Learns from Its Errors,” New York Times, June 28, 2002, late ed., A1.

6. C. Argyris, Overcoming Organizational Defenses: Facilitating Organizational Learning (Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon, 1990).

7. E. Goleman, Vital Lies, Simple Truths: The Psychology of Self-Deception (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1985); S. E. Taylor, Positive Illusions: Creative Self-Deception and the Healthy Mind (New York: Basic Books, 1989).

8. Edmondson and Cannon, “Failing to Learn and Learning to Fail (Intelligently).”

9. Taylor, Positive Illusions.

10. Ibid.

11. C. Fishman, “No Satisfaction at Toyota,” Fast Company 111 (2006): 82.

12. S. Finkelstein, Why Smart Executives Fail and What You Can Learn from Their Mistakes (New York: Portfolio Hardcover, 2003), pp. 179–180.

13. Ibid.

14. F. Lee, A. C. Edmondson, S. Thomke, and M. Worline, “The Mixed Effects of Inconsistency on Experimentation in Organizations,” Organization Science 15, no. 3 (2004): 310–326.

15. A. C. Edmondson, “Strategies for Learning from Failure,” Harvard Business Review 89, no. 4 (2011).

16. K. E. Weick and K. H. Roberts, “Collective Mind in Organizations: Heedful Interrelating on Flight Decks,” Administrative Science Quarterly 38 (1993): 357–381.

17. K. E. Weick and K. M. Sutcliffe, Managing the Unexpected: Resilient Performance in an Age of Uncertainty (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2007).

18. Weick and Roberts, “Collective Mind in Organizations.”

19. A. C. Edmondson and L. Feldman, “Phase Zero: Introducing New Services at IDEO (A),” HBS Case No. 605–069 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2005).

20. T. S. Burton, “By Learning from Failures, Lilly Keeps Drug Pipeline Full,” Wall Street Journal, April 21, 2004, B1.

21. Edmondson et al., “The Recovery Window.”

22. A. Taylor III, “Fixing up Ford,” CNNMoney, May 12, 2009. Available from http://money.cnn.com/2009/05/11/news/companies/mulally_ford.fortune/?postversion=2009051103.

23. S. W. Brown and S. S. Tax, “Recovering and Learning from Service Failures,” Sloan Management Review 40, no. 1 (1998): 75–89.

24. D. A. Garvin, Learning in Action (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2000).

25. F. F. Reichhel and T. Teal, The Loyalty Effect: The Hidden Force Behind Growth, Profits, and Lasting Value (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1996), pp. 194–195.

26. Burton, “By Learning from Failures.”

27. S. Thomke, Experimentation Matters: Unlocking the Potential of New Technologies for Innovation (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2003).

28. A. L. Tucker, I. M. Nembhard, and A. C. Edmondson, “Implementing New Practices: An Empirical Study of Organizational Learning in Hospital Intensive Care Units,” Management Science 53, no. 6 (2007): 894–907.

29. Lee et al., “The Mixed Effects of Inconsistency.”