Chapter Six

Teaming Across Boundaries

On August 5, 2010, more than half a million tons of rock suddenly caved in, completely blocking the entrance to the San Jose copper mine in Chile.1 Mining accidents are unfortunately common. But this one was unprecedented for several reasons: the distance of the miners from the Earth’s surface, the sheer number of miners trapped, and the hardness of the rock, to name a few. Thirty-three men were buried alive 2,000 feet under rock harder than granite. By way of comparison, an earlier rescue at the Quecreek Mine in Pennsylvania, with nine miners trapped 240 feet below ground, had been considered a remarkable feat.2 In Chile, initial estimates of the possibility of finding anyone alive were put at 10 percent—odds that diminished sharply two days later when rescue workers narrowly escaped a secondary collapse and forever shut down the option of extracting miners through the ventilation shaft.3

Most readers will already know that within 70 days all 33 miners would be rescued. What happened during those 70 days was an extraordinary teaming effort involving hundreds of individuals spanning physical (those 2,000 feet of rock), organizational, cultural, geographic, and professional boundaries.

Teaming took place in three main arenas. First, and most painful to consider, were the miners facing the challenge of physical and psychological survival. In the second arena, engineers and geologists came together from multiple organizations and nations to work on the technical problem of locating, reaching, and extracting the trapped miners. The political and managerial sphere comprised the third arena, where senior leaders in the Chilean government and elsewhere made decisions and provided resources to support the actions of those above and below ground at the San Jose site. At the outset, these three arenas contained independent teaming activities; by the end, their successes brought them together in a dramatic, magnificently choreographed rescue.

• • •

Below ground, amid shock and fear, leadership and teaming took shape after a tumultuous beginning. Immediately after the collapse, the miners scrambled to safety in the mine’s small “refuge.”4 Luis Urzúa, who had formal leadership over the group as the shift supervisor, started by checking provisions in the refuge. Calmly and quickly, he began to focus on crucial survival needs, especially in terms of the limited food available (roughly the amount of food two miners would eat over two days). Calm did not prevail, however. Mario Sepulveda, a charismatic 39-year-old, outraged at the state of the mine and the company’s long-standing lack of attention to safety, reacted angrily to the collapse. His energy attracted followers; factions and conflict soon emerged. Some wanted to take action of any kind to reach the outside rather than sitting helplessly to await rescue. Others wanted to follow Urzúa’s guidance. By the end of their first twenty-four hours, the miners were exhausted by failed attempts to communicate with the outside world and disoriented by the lack of natural light. With scant attention to sanitation or order and subdued by hunger and fatigue, they attempted to sleep.

On the second day, miner Jose Henriquez stepped in to urge the group to start each day with a collective prayer. Soon this became a sustaining routine and helped unite the group around a shared goal of survival. With no blueprint for how to survive in these conditions, conversation and experimentation were essential to discovering a way forward. In the days that followed, facing darkness, hunger, depression, filth, and illness, the miners cooperated intensely to maintain order, health, sanitation, and sanity. They used the lighting system to simulate day and night, each lasting twelve hours. Sepulveda, determined now to pull people together, assigned specific tasks to people based on skills, experience, and mental stability. No responsibilities were imposed on miners who were hallucinating or were otherwise incapable of focused action. When some miners began to develop skin mold and canker sores from the heat and humidity, miner Yonni Barrios, well read on various illnesses, volunteered as a medic. A grim but functional routine took hold, dampening the cycles of despair and hope. Seventeen days later, when rescuers finally bored a narrow hole into the chamber, the miners received additional food and supplies and the lifeline of communication by special telephone.

• • •

Above ground, the Chilean Carabineros Special Operations Group—an elite police unit for rescue operations—arrived a few hours after the first collapse. Their initial attempt at rescue led to the ventilation shaft collapse that was the rescue effort’s dismal first failure. As news of a mine cave-in spread, family members, emergency response teams, rescue workers, and reporters also flooded to the site. Meanwhile, others in the Chilean mining community dispatched experts, drilling machines, and bulldozers. Codelco, the state-owned company overseeing the San Jose mine, sent Andre Sougarret, an engineer and manager with over twenty years of experience in mining who was known for his calm, composure, and ease with people, to lead the operation.

Working with numerous other technical experts, Sougarret formed three teams to oversee different aspects of the operation. One searched for the men, poking drill holes deep into the earth in the hopes of hearing sounds to indicate that the men were alive. Another worked on how to keep them alive if found, and a third worked on how to extract them safely from the refuge. The teams originally came up with four possible rescue strategies: the first, through the ventilation shaft, was quickly rendered impossible, as noted earlier. The second, drilling a new mine ramp, also proved impossible once the rock’s instability was discovered. The third, tunneling from an adjacent mine a mile away, would have taken eight months and was also excluded. The only hope was to drill a series of holes at various angles in an attempt to locate the men.

But the extreme depth and small size of the refuge made the problem of location staggeringly difficult. With the drills’ limited precision, the odds of hitting the refuge with each painstaking drill attempt were about one in eighty.5 Even that was optimistic, because the location of the refuge was not precisely known. Available maps of the tunnels were inaccurate, having not been updated in years. Worse, the drillers couldn’t take the most direct route, mounting equipment in such a way as to drill straight down on top of the mine because it would increase the danger of collapse. Instead, they would have to set up off to the side and drill at an angle, further complicating the accuracy problem.

To maximize the chances of success, teams worked separately at first to come up with different strategies for drilling the holes. Several early attempts failed to reach the miners, but at least revealed crucial features of the mine and the rock. Unfortunately, much of this learning brought bad news. For instance, the drillers and geologists discovered that fallen rock trapped water and sedimentary rocks, increasing drill deviations and further reducing the chances of reaching the refuge in time. They also learned that drilling at an inclined angle shifted the drill to the right, while the weight of the drill bars pushed the drill upright, giving rise to an overall drift downward and to the right. This was the kind of technical detail that engineers had to quickly incorporate into their plans, which were changing rapidly and radically with each passing day.

One dramatic change to procedure was the discovery and use of frequent, short action-assessment cycles. In normal drilling operations, precision was measured after a hole was completely drilled. Here, in contrast, drillers realized that to hit the refuge, they would have to make measurements every few hours and promptly discard holes that deviated too much, starting again—discouraging as that might be. As they learned more about the search challenge, the odds of success diminished further, with one driller putting it at less than 1 percent.

Fortunately, the different teams came up with remarkably complementary pieces of an ultimately viable solution. For example, in one piece of good luck, a Chilean geologist named Felipe Matthews, who had developed a unique technology for measuring drilling trajectories with high precision, showed up at the site with his innovation. He discovered quickly that his measurements were inconsistent with those of other on-site groups. Based on a rapidly improvised series of tests, Matthews’s equipment was found to be most accurate, and he was put in charge of measuring the accuracy of all drilling in progress.

The various subgroup leaders met for a half hour every morning and also called for quick meetings on an as-needed basis. They developed a protocol for transitioning between day and night drill shifts and for routine maintenance of machinery. “We structured, structured, structured all aspects of execution”6 As drill attempts continued to fail, one after another, Sougarret communicated gracefully with the families. Despite these failures, Sougarret and his new colleagues persevered.

• • •

Meanwhile, in Santiago, the newly elected Chilean president, Sebastian Piñera, had met with Mining Minister Laurence Golborne on the morning of August 6, 2010. The president sent Golborne to the mine with clear instructions: Get the miners back alive and spare no expense. Further, this intention was to be made entirely public. This was a critical decision by a man with prior experience in business rather than government; someone with political savvy might have avoided staking his reputation on a promise so unlikely to be realized. Golborne and Piñera quickly reached out to their network, which comprised colleagues around the world. As the president put it, “We were humble enough to ask for help.”7 Michael Duncan, a deputy chief medical officer with the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) who was contacted by the government, concurred, reporting that the Chilean officials basically said, “Let’s try to identify who the experts are in the field—let’s get some consultants in here that can give us the best information possible.”8 Duncan, for example, brought experience with long space flights to bear on the question of the miners’ physical and psychological survival in small quarters. NASA engineers played a crucial role in the design of the escape capsule, leading us to the final teaming endeavor in the technical realm, thousands of miles from the site.

Clint Cragg, a top NASA engineer, went to Chile in late August with a few NASA health care experts to volunteer to help.9 Cragg later teamed with engineers in the Chilean navy to design the rescue capsule, after first going back to the United States to pull together a group of 20 NASA engineers. For inspiration, the NASA team looked to a precedent dubbed the “Dahlbusch Bomb,” built in 1955 to rescue three men trapped in the Dahlbusch coal mine in western Germany. The engineers developed a twelve-page list of requirements, used by the Chilean navy in the final design for the capsule, which was called the Fenix. The Fenix interior, just barely large enough to hold a person, was equipped with a microphone, oxygen, and spring-loaded retractable wheels to roll smoothly against the rock walls. The engineers designed three nearly identical capsules. The first was used during tests—experiments and dry runs—and the second was used during the rescue operation. The third, presumably, was a backup. On October 13, the Fenix started its life-saving runs to bring miners one by one through the fifteen-minute journey to the surface of the Earth. Over the next two days, miners were hauled up one by one in the twenty-eight-inch-wide escape capsule painted with the red, white, and blue of the Chilean flag. After a few minutes to hug relatives, each was taken for medical evaluation.

Teaming Despite Boundaries

Reflecting on the Chilean rescue, it is clear that a top-down, command-and-control approach would have failed utterly. No one person, or even one leadership team, could have figured out how to solve this problem. It’s also clear that simply encouraging everyone to try anything they wanted would have produced only chaos and harm. Family members, miners, and others with good intentions had to be held back numerous times from rushing headlong at the rock with pickaxes. Instead, what was required, facing the unprecedented scale of the disaster, was coordinated teaming—multiple temporary groups of people working separately on different types of problems, and coordinating across groups, as needed. It also required progressive experimentation. This section considers key factors to the operation’s success, and what we can learn from the case about teaming across boundaries more generally.

First, the most senior leadership committed publicly to a successful outcome, risking both resources and reputation on an unlikely outcome. In his decision to do this, President Piñera resembles other leaders facing nearly impossible challenges who have been willing to declare an early and total commitment to success. Take, for example, the explosion that occurred in an oxygen tank during the Apollo 13 mission on its journey to the moon. Despite limited resources, unclear options and a high probability of failure, NASA flight director Gene Krantz insisted, “Failure is not an option.” He authorized problem-solving efforts in previously trained teams that tirelessly worked out scenarios for recovery using only materials available to the astronauts.10 Ultimately, Kranz and his teams safely returned the crew to Earth. Piñera and Golborne were also willing to ask for help and to seek out expertise in any organization or nation willing to provide it.

Second, the teaming utilized rapid-cycle learning. Technical experts worked collaboratively to design, test, modify, and abandon options, over and over again, until they got it right. They organized quickly to design and try out various solutions, and just as quickly admitted when these had failed. They willingly changed course based on feedback—some obvious (the collapse of the ventilation shaft), some subtle (being told that their measurements were inaccurate by an engineer intruding mid-process with a new technology). Perhaps most important, the engineers did not take repeated failure as evidence that a successful rescue was impossible. Similarly, the miners successfully teamed to solve the most pressing problems of survival, despite the desperate odds.

Third, the structure of the teaming is interesting to consider. The separate efforts—managerial, technical, and survival—were intensely focused. In each arena, problem solving was intelligent and persistent, and the combined efforts equaled more than the sum of the parts. The intermittent coordination between the arenas was as important as the intense improvisation and learning within them.

As this example demonstrates, when teaming across boundaries works, the results can be awe-inspiring. Managing a complex rescue operation, launching a space shuttle, producing a big-budget movie, or delivering a large engineering and construction project are all examples of complex uncertain work that requires multiple areas of expertise, and even multiple organizations, for its completion. The problem is that all too often teaming is thwarted by communication failures that take place at the boundaries between professions, organizations, and other groups. People think they’re communicating, they participate in endless meetings, and they work hard, only to have their projects fail. Why? As individuals bring diverse expertise, skills, perspectives, and goals together in unique team configurations to accomplish challenging goals, they must overcome the hidden challenge of communicating across multiple types of boundaries. Some boundaries are obvious—2,000 feet of rock, or being in different countries with different time zones. Others are subtle, such as when two engineers working for the same company in different facilities unknowingly bring different taken-for-granted assumptions about how to carry out a particular technical procedure to a collaboration.

This chapter describes the boundaries that team members frequently must cross while working together on complex problems. After examining why boundaries matter, I describe three types of boundaries that confront teaming in today’s global organizations. I then provide guidelines for successfully teaming across boundaries to create possibilities for organizational learning.

Visible and Invisible Boundaries

Boundaries refer to the divisions between identity groups. An identity group exists around any meaningful category in which a person belongs, such as gender, occupation, or nationality. Some identity groups, and their corresponding boundaries, are more visible than others. Gender, for example, is visible. Occupation is less visible—except where clothing gives it away. What is invisible, however, are the taken-for-granted assumptions and mindsets that people hold in different groups. For teaming to be successful, managers and team members must be aware that they come together with different perspectives, often taking for granted the “rightness” of their own beliefs and values. This means it’s not enough to simply say, let’s band together, and it will all work out. No matter how much goodwill may be involved, boundaries limit collaboration in ways that are often invisible but nonetheless powerful.

Taken-for-Granted Assumptions

Processes of education, licensing, hiring, and socializing contribute to beliefs that lead people to favor their own group or location, and to unconsciously view the knowledge of their own group as especially important. It’s as if there’s a wall that separates engineers from marketers; nurses from doctors; and designers in Beijing from designers in Boston. Most people take knowledge that lies on their side of a boundary for granted, making it hard to communicate with those on the other side. Paraphrasing an observation once made by communications theorist Marshall McLuhan, we don’t know who discovered water, but it wasn’t the fish. In other words, the context in which we work, day in and day out, is often invisible to us. Presumably, fish don’t think much about water; they take it for granted. Research on cross-functional new product development teams conducted by Professor Deborah Dougherty of Rutgers found that team members from different areas of expertise occupied different “thought worlds”—taken-for-granted assumptions that each expert was unaware of holding.11 Similarly, each of us takes for granted many of the values and norms of identity groups (profession, organization, country, and so on) of which we’re members. At its core, teaming is about reaching across or spanning these kinds of boundaries. To do this, we must first be keenly aware of what they are. Many boundaries were created and strengthened by the very people—experts, department heads, authorities—who now must play a role in helping to break them down.

Communication with anyone from a different group, whether the difference is demographic or organizational, is fraught with small hurdles. Teams within organizations often must coordinate objectives, schedules, or resources with other teams, departments, or locations. This requires discovering and revealing taken-for-granted assumptions to avoid misunderstanding and error. But by their very nature, taken-for-granted assumptions are notoriously hard to recognize, so it helps to be aware that they exist and to be on the lookout for them. Consider the real-life example of two aeronautical organizations that joined forces to collaborate on a new aircraft. At the first planning meeting, everyone agreed on ambitious goals and a rigorous schedule. However, the conversation kept getting mired in misunderstanding and miscommunication. Finally, it was discovered that the two groups meant something different when they used the simple phrase “the plane has been delivered.” One organization understood it to mean the plane has been physically delivered to a control station. But the other organization understood the exact same phrase to mean the plane has been delivered to the physical site and the machinery has passed all technical inspection. In addition to the head-scratching in the room, this semantic difference was crucial to the project because it affected how data was to be collected and categorized. This subtle difference in semantic use between two aeronautical groups is just a single example of the kind of misunderstanding that can be multiplied many times over when teaming spans boundaries.

To further add to the challenge, research by Miami University professor Gerald Stasser and his colleagues shows that unique information held by any one team member, as opposed to information shared by most team members, is often ignored in team decisions, much to the detriment of team performance.12 It is natural for people from different groups to come together and spend precious time discussing the subset of knowledge with which everyone is already familiar. Unique information rarely surfaces, even when that information is critical to making the decision. Groups don’t mean to do this. In fact, people in groups often believe they are leveraging group member expertise to make an informed decision. These well-documented findings describe groups that are left to their own devices, without leadership or tools to guide their process. Fortunately, as we will see later in this chapter, it is possible to avoid these traps.

Specialization and Globalization

Two related trends have increased the need for teaming across boundaries. First, knowledge and expertise evolve ever more rapidly. In most fields, the rate of new knowledge development requires people to invest considerable time just to stay current in their own area of expertise. Especially in technical fields, the explosion of new knowledge leads inexorably to greater specialization. Fields spawn new subfields, and new subfields spawn even more specialized subfields. For example, electrical engineering, once a subfield of physics, became its own discipline by 1900, and today splits into the several distinct subfields of power systems, signal processing, and computer architecture. More generally, technical knowledge and specialized jargon proliferate, making it difficult to keep up with other, even closely related, fields of inquiry. Highly specialized professionals thus find themselves needing to collaborate to carry out the important work of the organization, whether developing a new cell phone or caring for a cancer patient.

Second, global competition has led to ever more compressed time frames: product life cycles are shrinking; lead times for getting new products to market are shorter; and scientific researchers face more threats of being scooped in their work by a lab halfway around the world. Time pressures mean that a structured approach, in which managers plan each aspect of a large development project with specialized tasks to be accomplished separately in carefully structured phases, are unrealistic. This planning becomes even less realistic when completed tasks are “thrown over the wall” to other functions or disciplines. Instead, the walls between disciplines have come down, and simultaneous work on related tasks must be coordinated and negotiated in a dynamic teaming journey.

Individuals or departments cannot accomplish meaningful results in isolation. The chances of individual components, developed separately, coming together into meaningful, functional wholes—new product, feature film, or rescue operation—without intense communication across the boundaries are exceedingly low. Considering these two factors—increasing specialization and global competition—there are numerous benefits to learning how to transcend boundaries that exist between people, departments, or specialties. Understanding how to break down these walls includes developing a deeper understanding of the varieties of diversity and how they relate to the boundaries that exist both within and between work groups.

Three Types of Boundaries

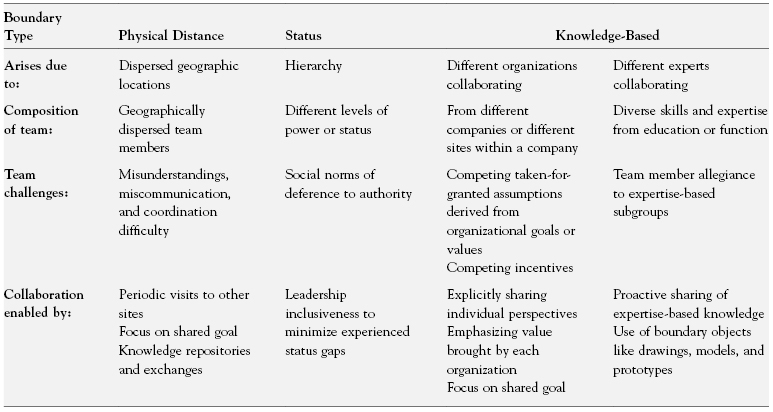

Diversity is an important topic in research on teams and teaming, yet researchers lack consensus on a single clear definition of diversity. Katherine Klein and Dave Harrison, professors at Wharton and Penn State, respectively, defined diversity as “the distribution of differences among the members of a unit with respect to a common attribute X.”13 Common attributes include gender, ethnicity, professional status, and educational degree. A team is considered diverse if its members differ in respect to at least one attribute. Conceptually, Klein and Harrison grouped diversity into three basic groups, separation, disparity, and variety, which provides a helpful starting point. Exhibit 6.1 uses these distinctions to suggest three common boundaries that often confront teaming in complex organizations.

- Physical distance: Separation diversity includes differences in location—different time zones or the building down the street.

- Status: Disparity diversity ranks people according to the social value of a particular attribute. Teaming often confronts differences in status between people who need to work together to get a job done.

- Knowledge: Variety diversity describes differences in experience, knowledge, expertise, or education. When teaming, the major boundaries confronted in this category are differences in knowledge based on organizational membership or expertise.

The following sections look at examples of each of these types of boundaries and consider their impact on collaboration. Of course, sometimes people must cross multiple boundaries at once, such as when two team members have differences in terms of nationality, profession, gender, and time zone. Fortunately, leadership that helps establish process discipline and good communication can help overcome the challenges described in this section.

Physical Distance

An increasingly common teaming challenge is created by the need to span geographic distance. In many global companies, work teams in geographically dispersed locations all over the world, so-called virtual teams, are relied on to integrate expertise. A virtual team is a group of individuals who work across physical and organizational boundaries through the use of technology. (Later in this chapter, I describe one such project in a global company.) Geographic regions in some organizations present nearly impermeable boundaries, even within the same country. At the Internal Revenue Service, for example, before Commissioner Charles Rossotti led the agency in an ambitious organizational transformation during his five-year tenure under President Bill Clinton, regional centers had acted like fiefdoms for decades, sharing neither information nor resources, despite the need to do both. Service representatives were unable to respond to the volume and variety of complex tax questions that would come into the regional center. The result was poor service and frustrated customers. Rossotti took down the regional barriers by combining all service representatives into one centralized national call center. Employees did not physically move. They still lived and worked in the old geographic locations, but they became part of one large virtual service team that was able to spread the workload in sensible and equitable ways.14 This organizational change allowed taxpayers’ technical queries to be routed to those individuals with expertise in a particular aspect of the tax code—no matter where they were located.

Status Boundaries

Disparity diversity may be the most challenging boundary to cross in teaming. When those at the top have the most power and those at the bottom have the least, lower-power individuals usually find it hard to speak up. Perhaps the most common power differences within work teams are professional status and ethnicity. Professional status can significantly affect beliefs about taking interpersonal risks and speaking up. In health care, for example, physicians have more status and power than nurses, who in turn have more status than technicians. Yet members of these professions often must team to take care of patients. Even people from the same profession can have status differences. Consider resident-level and senior (“attending”) physicians working together to care for patients. Fears about taking interpersonal risk can prohibit candid discussion and hinder collaboration. Yale professor Ingrid Nembhard and I conducted a study of intensive care units (ICUs) in which we found that the status differences that exist between physicians, nurses, and respiratory therapists led to significant differences in psychological safety across these groups, which affected their willingness to speak up, ask questions, and participate in improvement efforts.15 When we looked at the data more closely, we discovered that some unusual ICUs didn’t show any status-based difference in psychological safety. Instead, these units were workplaces where everyone, no matter what role, felt equally engaged and able to participate in the collaborative work of caring for patients. These units also showed significantly more clinical improvement in outcomes over the two years of the study.16

My recent research with Professor James Detert of Cornell (described in Chapter Two) uncovered taken-for-granted beliefs about speaking up in hierarchies that pose a real challenge to cross-status teaming. Each of us, without consciously realizing it, has well-learned taken-for-granted rules for when to openly share our ideas, concerns, or questions with people above us in an organizational hierarchy. For example, many tacitly assume that ideas for change will be seen by senior managers as a criticism (whether or not that’s accurate). And most people are naturally reluctant to avoid criticizing people in positions of power.17

Note that demographic differences (differences based on gender, race, religion, and other social categories), which may readily be seen as variety diversity, sometimes also enforce a power hierarchy due to the nature of social power in various cultures and countries. For example, power and status differences in organizations have been documented for both gender and race.18 In addition, individuals aware of negative stereotypes associated with cultural identity may become hindered by self-fulfilling prophecies or a perceived need to overcome negative stereotypes.19 Similarly, unconscious negative stereotypes significantly hinder group performance because individuals tend to skirt or avoid the issue, allowing negative stereotypes to arise in other, more subtle ways.20

Knowledge Boundaries

Work teams often confront differences in expertise. In product and process development teams, for example, it is increasingly common to bring together people from different organizational functions for a limited period of intense teaming. The value of teaming is that different experts bring different knowledge and skills to the collaborative task. In product development, engineering offers insight into design and technology; manufacturing into feasible production processes, accurate cost estimates, pilot and full-scale production; and marketing into customer receptivity, customer segments, product positioning, and product plans. Teaming is the process of integrating these diverse skill sets and perspectives, as well as coordinating timelines and transferring resources across groups, when appropriate. However, diverse groups often have difficulty accessing and managing disparate knowledge, for two reasons. Misunderstandings arise due to different meanings embedded in different disciplines, and mistrust arises between groups.

Teaming Across Common Boundaries

Sharing knowledge across boundaries may not be natural in large organizations, but it’s certainly worth the effort. Successfully overcoming the obstacles of teaming across boundaries offers valuable learning for individuals and provides a vital competitive advantage for organizations. Working across the three types of boundaries described in the previous section requires attention to their unique challenges and to techniques for overcoming them. For reference, Table 6.1 summarizes these common boundaries and their accompanying tactics.

Table 6.1: Common Boundaries That Impede Teaming and Organizational Learning

As shown in Table 6.1, physical and status differences arise from distance and hierarchy, respectively, whereas knowledge boundaries arise from two distinct origins—membership in different organizations and membership in different occupations. The following sections explore the implications of teaming across each boundary and present strategies for successful teaming and learning within diverse groups.

Teaming Across Distance Boundaries

“Sharing is not a natural thing,” said Benedikt Benenati, the organizational development director at the multinational food company, Groupe Danone.21 With subsidiaries in 120 countries, Groupe Danone is a multinational corporation that sought to promote teaming across the geographical boundaries of its many divisions. In addition to sharing common problems, such as getting retailers to stock the right amounts of Danone products at the right time, managers in different countries were focused on their own regions, and rarely considered the opportunity to seek ideas from their counterparts in other regions. As Benenati pointed out, the company’s senior managers may be part of the problem: “Managers may be reluctant to let their teams discuss among themselves. If members of their team find solutions, then perhaps managers are of no further use.”22 Such reactions and fears are very human, of course, but they also leave opportunities for small process improvements around the globe to go untapped.

Benenati put the need for knowledge sharing in blunt, practical terms: “In a company with 90,000 employees, solutions to the problems of one team are likely to exist elsewhere.”23 To facilitate knowledge sharing and immediate collaborations among people in different locations, but with similar responsibilities, Benenati and his colleague, Franck Mougin, executive vice president of human resources, created what they called Knowledge Marketplaces. These marketplaces were like small improvisational performances punctuating the usual business routine. Nested within regular company conferences, Knowledge Marketplaces took place when managers from across the globe were gathered in one location. Participants in the marketplace wore costumes to mask hierarchical levels and encourage sharing of business and operations ideas. Interacting with a senior vice president in a Yoda mask was less intimidating than approaching that same executive dressed in a suit and tie. Likewise, a new associate dressed as Darth Vader might feel empowered to speak up in ways she might not feel in regular office attire. The atmosphere was clearly playful, and many remarked that the costumes made it easy to trade ideas and practices.

Although spontaneous exchanges of ideas and practical suggestions abounded in the Danone Knowledge Marketplaces, some knowledge exchanges were orchestrated in advance. For these, selected managers were instructed to prepare books with stories of best practices that facilitated successful knowledge sharing. One such book described how the marketing team at Danone Brazil helped the marketing team in Danone France launch a new fat-free dessert. By adapting an existing product from Brazil, Danone France was able to bring a new product to the French market in less than three months. Not only was time saved, but a €20-million business was created with sales superior to the closest competitor. This occurred, however, as a result of Danone’s leadership designing a kind of social engineering to overcome the natural tendencies for practical knowledge not to flow across geographic boundaries. When teams or groups do not have the ability to physically meet and exchange ideas, they must rely on technology to span distances, and communicating through information technology brings its own problems.

The information technology that allows us to shrink global distances by sending e-mails hurtling through cyberspace and to fax documents to machines across continents gives us a false sense of security, lulling us into believing that teamwork among geographically dispersed employees requires nothing more than a fast Internet connection or new videoconferencing equipment. In fact, there are substantial barriers to sharing and integrating knowledge that virtual teams must overcome. In some organizations, however, it’s the different mindsets across geographic regions, rather than the actual physical distance between them, that present nearly impermeable boundaries. In addition to the obvious challenges brought on by language and time zone differences, some types of knowledge just do not travel well. This is because certain, often very valuable, information is taken for granted by those who are closest to it. This tacit knowledge can be situated in ways that make it invisible to distant team members.

Collaboration across distance boundaries is greatly enabled by coming together physically, if possible, for a rare but valuable face-to-face meeting. This helps build trust and awareness of differences that might have to be taken into consideration during collaborative work. The Knowledge Marketplaces at Danone were an example of this technique. It’s also helpful to emphasize a shared goal, to motivate the effort of communicating across distances. A shared goal clearly helped motivate teaming across distance boundaries in the Chilean rescue, for example. And, despite the various challenges of using IT systems effectively, computer-based knowledge management (KM) systems in large companies remain a crucial tool for helping people team across distance boundaries. Recent research shows that globally dispersed software project teams that used knowledge repositories more frequently than their counterparts performed better in both quality and efficiency.24 The use of stored knowledge, developed by engineers around the world, provided these complex temporary teams with valuable information and techniques that accelerated and improved their collaborative work.

Teaming Across Status Boundaries

Most organizations contain vestiges of hierarchical boundaries. Although a command-and-control model of authority may have been productive in the past, the knowledge economy increasingly requires interactive communication and collaboration. The many problems that hierarchy creates for collaboration have been mentioned in previous chapters. I have also offered practical solutions to the corrosive and stifling effect of hierarchy. (See especially Chapter Four, Making It Safe to Team.) The principal strategy for developing the necessary level of collaboration, however, is leadership inclusiveness, in which higher-status individuals in a group actively invite and express appreciation for the views of others.25

Consider the case of Patti Bondurant, senior clinical director at the Regional Center for Newborn Intensive Care at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. Bondurant felt that having the respiratory therapists, rather than the physician-director of the unit, lead an improvement project was a key driver to their improvement. She described this new relationship as follows:

The turning point for us was when our respiratory therapy clinical managers in all three of the units said, “With all due respect, doctor, this is our expertise and you need to let us do our job.” It was a really defining moment for this group. The doctor sat back and said, “I believe you’re right. I don’t need to hang onto control when there are people willing to do the work.” … Those doctors were open to say, “Yes, you’re the experts and we’re going to let you do your job.” The dynamic shifted from doctor sitting at the head of the table, to all of us becoming common denominators at the table.26

This is a “textbook moment” of teaming across hierarchical boundaries. The respiratory therapy clinical managers, lowest on the ladder, felt valued enough to speak clearly and directly to their institutional superiors with both expertise and a point of view. The doctors, at the top of the ladder, were able to sit back, listen, agree, and learn, thereby relinquishing control over every aspect of the project. Most important, spanning this boundary allowed a renegotiation of responsibilities, which in turn allowed improved care for the newborn patients.

Teaming Across Knowledge Boundaries

Organization and occupation are two important sources of knowledge boundaries. The former exists anytime people from different companies—or even sites within companies as we saw at the IRS—have to work together. The latter is driven by differences in areas of expertise, within and between organizations.

Organization-Based.

Organizational membership brings with it taken-for-granted, or “tacit,” knowledge shared by other members of the same organization. People working together acquire shared experiences and practices that begin to seem (to them) like the obvious right way to do things. This tacit knowledge might consist of expectations about a particular supplier’s reliability, the performance of a particular piece of equipment, or even awareness of who knows what in a given facility. Some things you just have to be on site to know. And because this kind of knowledge is taken for granted, people often don’t realize that what they know is important to share. It is also the case that these kinds of knowledge boundaries often coexist with distance boundaries, which further raises the communication hurdle.

Consider the example of a new product development team in a large highly technical business charged with carrying out a project to develop a polymer for a new customer in a strategic market sector. With seven people dispersed across five sites on three continents, teleconferencing allowed the team extensive brainstorming and discussion, yet one ingredient for the new polymer proved unexpectedly difficult to source. One member of the team, an engineer in the United Kingdom whom I’ll call David Thompson, turned to his local, on-site colleagues for help. As Thompson tells it, he was “just talking” when a colleague at his site happened to mention that he was making the difficult-to-source ingredient and could reserve a barrel for Thompson’s team. It’s the “just talking” around the proverbial watercooler that is situational, often crucial, and easily misunderstood by distant colleagues.27

Perhaps it’s no surprise that tacit knowledge still figures prominently in the twenty-first century, despite vast technical advances. One of the greatest challenges of teaming is finding ways to augment high-tech mediated collaboration by actively seeking out tacit knowledge to use in other locations. The trick for accomplishing this is for each team member to enroll his or her local colleagues by keeping them in the loop with basic project updates. That way, they can offer relevant knowledge, both technical and organizational, when needed. This scouting activity often involves lateral and downward searches through the organization to understand who has relevant knowledge and expertise.28 Periodic visits are also wonderful ways to uncover tacit knowledge! Research on virtual teams has shown that visiting each other’s sites is a powerful way to foster trust, understanding, and collaboration.29 When teams are able to discover and leverage site-specific tacit knowledge, they are better able to take advantage of their diverse knowledge. Emphasizing the value brought by each organization helps this happen.

Occupation-Based.

Training for any one profession is often a long process of mastering a specialized body of knowledge, terminology, and above all, a mindset or way of knowing. Business students learn about marketing, management, and how to interpret company problems. Medical students learn about ligaments, blood vessels, and how to recognize disease. Writers learn about how to use language. Each profession is trained to make particular assumptions and epistemological assertions, which often become taken for granted. Jargon, acquired in specialized education and practice, often means that occupations speak different languages. This makes sharing across the “thought worlds” of occupational communities highly vulnerable to misunderstanding. In many cases, meaning is lost, errors are made, and synergy fails to materialize.

Expertise diversity is a key source of innovation. Individuals from different groups weave their ideas and knowledge into new, integrated forms. This type of synthesis is tricky even in mature industries, but particularly when confronting new or novel problems, as occurred in the Autodesk building project (discussed later). Colocation, along with a lot of communication, and excitement about the innovative building they were trying to build, were essential to the team’s ability to build trust across occupational boundaries that had long been antagonistic in the industry. Working across occupational boundaries is replete with technical and interpersonal challenges. It also comes with the territory of cross-functional teams.

Teams with occupational and expertise differences aligned with organizational departments or functions are termed cross-functional teams. Such teams are on the rise in organizations, especially for innovation projects. The goal of cross-functional teaming is to bring together experts of various kinds who can combine knowledge gleaned from their distinct training to produce results that can’t be achieved by any single discipline. Cross-functional teams are useful in organizations because they serve as a mechanism for combining different sets of highly specialized skills into one cohesive group. The obvious benefit of this form of collaboration is the qualified, high-level information that can be provided by each team member.

For example, cross-functional teaming allowed Dr. Fred Ryckman, a transplant surgeon at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and Medical Center, to overcome seemingly insurmountable capacity constraints in operating room scheduling. The hospital needed at least one more operating room (OR) to accommodate the increased surgical volume. Because of this limitation, patients had to wait longer for care and surgeons had to work longer hours than might be safe. But a new operating room costs upwards of $2.5 million; money that would be difficult and time-consuming to raise. Unfortunately, tackling the capacity problem with the other surgeons failed to produce any viable solutions. Everyone understood the need to share available resources, but no one could figure out how to stretch the hours in a day to meet the rising demand.

Instead, by teaming with a computer scientist and a statistician, Ryckman was able to explore different, innovative possibilities. The statistician abstracted the problem into one of numbers: arrival times, procedure times, and dates. The computer scientist reorganized the data and ran complex analyses. In very little time, a team of experts with varied backgrounds was working to figure out ways to redesign the existing system for operating room allocations. Only when Ryckman began teaming cross-functionally did a solution begin to seem possible. Professionals outside the operating room asked questions that Ryckman had never considered. The resulting changes reoriented what were previously thought of as natural assumptions about OR capacity and scheduling. Together, Ryckman and his team created a model that dramatically altered and improved how operating rooms were used. They discovered that how patients flowed through the hospital system made a huge difference in how well operating rooms were used. The details, in Ryckman’s own words, illuminate how this works:

By smoothing our OR flow and dedicating different ORs for scheduled surgeries versus unscheduled emergency surgeries, we were able to increase throughput by five percent. This doesn’t seem like a big deal, but we run 20 operating rooms, so a five percent increase equals one additional OR being available. It costs $2.5 to $3 million to build a standard OR that can do typical procedures. A neurosurgery room with an integrated MR [magnetic resonance] suite can cost almost $10 million. If you can go in and manage it better, you won’t have to build a new room.30

Research has shown that the challenge of occupational boundary spanning can be mitigated through the use of what are called boundary objects around which diverse groups can coalesce. Boundary objects like drawings, prototypes, and components are tangible representations of knowledge. Professor Paul Carlile of Boston University studied knowledge barriers in new product development teams in the automotive industry. He found that boundary objects facilitated spanning occupation and expertise boundaries. By pointing to and discussing elements in a model or schematic, the obfuscating qualities of jargon can be overcome.31 Similarly, University of California, Davis professor Beth Bechky has found that while working face to face in a production facility engineers, technicians, and assemblers can cocreate meaning, reaching across the boundaries between practices to do so.32 This process, which generates fuller understanding of the products and problems they face, involves more than just discussion, but also shared action; for example, convening around a common machine or drawing to articulate different perspectives and develop a shared understanding. It also facilitates sharing expertise-based knowledge.

Occupation and Organization Combined.

When knowledge boundaries based on expertise or profession are confounded with knowledge boundaries that exist between companies, the challenge intensifies. A complex building project, for example, brings together multiple areas of expertise as well as multiple companies to produce a customized product with unique constraints and goals. Participants in this process—owners, architects, engineers, and builders—have traditionally managed the manifold risks they face through legal contracts rather than through teaming, leaving the industry with a history of deep mistrust between professions.33 The next section includes discussion of a strategy for overcoming the mistrust and misunderstandings that these organizational boundaries have created.

Some recent innovative building projects have attempted to change the counterproductive dynamics in the construction industry by teaming across boundaries from the beginning of a project until the very end. The goal is to avoid the small failures that are nearly inevitable in complex, unique projects, and of course to avoid large failures, too. My colleague Faaiza Rashid and I studied a project that employed such an approach, called Integrated Project Delivery (IPD). Individuals from the multiple companies and professions in a large building project agreed to work together closely from project start to completion. Locating together in one workplace near the building site, everyone signed a single legal contract. Despite aggressive targets in budget, deadline, aesthetics, and environmental sustainability that made the project especially challenging, the teaming worked, trust grew, and the result was an award-winning building for the Boston area headquarters of software company Autodesk.34

• • •

Teaming across boundaries of all kinds has the potential to help participants increase their knowledge of other fields. Working in diverse teams can expand participants’ networks of colleagues from other areas of the organization and improve their boundary-spanning skills. This last point is particularly important because most teams must work across more than one diversity type or organizational boundary to solve today’s most complex problems. In the next section, I offer suggestions to help leaders facilitate cross-boundary communication.

Leading Communication Across Boundaries

There are three actions leaders can take to facilitate communication across boundaries. First: frame a shared goal that unites people and motivates willingness to overcome communication barriers. Second: display curiosity to legitimize sharing information and asking questions. Third: provide process guidelines to help structure collaboration. Let’s look at each of these actions to see how they can make teaming across boundaries smoother in spite of the obstacles we’ve discussed.

Establish a Shared Superordinate Goal

In a complex teaming effort, individuals and subgroups have many small goals to achieve along the way (drill a hole without collapsing more rock, complete an aesthetically pleasing building design), but sharing an overarching or “superordinate” goal (rescue the miners, complete an ambitious building project on time and under budget), helps motivate people to communicate thoroughly and carefully. Emphasizing a shared goal (as discussed in Chapter Four) should be recognized as one of the core leadership framing tasks. A goal can be framed as something important and inspiring (helping patients recover faster) or as just another job (implementing a new technology). When the path forward to its completion is unclear, a superordinate goal should be framed as a learning opportunity. Framing a shared goal as a learning opportunity helps level the playing field and facilitates speaking up. This also helps to build a psychologically safe environment. Team members must feel safe asking what could be considered a “dumb question” in an effort to better understand each other’s “thought worlds.” They must be able to share their perspectives without embarrassment.

One extraordinarily successful cross-boundary teaming project was the design and construction of the Water Cube, the aquatics center built for the Beijing Olympics. The goal was clear and exciting: build a memorable, iconic building for swimming and diving that would reflect Chinese culture, integrate with the site, and minimize energy consumption. Because the design would compete in an international competition, everyone wanted it to be novel, exciting, and unique. And, of course, it had to be finished before the Olympic Games began. Moving from concept to completion in record time, the Water Cube utilized cross-disciplinary, cross-continent, and cross-organizational teaming. Led by Tristram Carfrae, principal and senior structural engineer at Arup in Sydney, Australia, the teaming involved more than 80 individuals from four organizations (Arup, PTW Architects, China State Construction and Engineering Company, and China Construction Design International), spread across twenty disciplines and offices in four countries.

Be Curious

To help people cross boundaries, leaders must display and encourage genuine curiosity about what others think, worry about, and aspire to achieve. By cultivating one’s own curiosity about what makes others tick, each of us can contribute to creating an environment where it’s acceptable to express interest in others’ thoughts and feelings. MIT professor Edgar Schein, a preeminent researcher on corporate culture, uses the term “temporary cultural island” in his description of a process for sharing crucial professional and personal information in a multicultural work group. The process involves talking about concrete experiences and feelings, and is fueled by thoughtful questions on the part of a leader, acting as a facilitator. Schein explains that cultural assumptions related to authority and intimacy are crucial issues in culturally diverse teams. When someone violates an authority rule that is taken for granted in one culture—for example, by speaking in an overly familiar manner to a high-status person—someone from another culture may experience it as jarring. By sharing stories in which these issues are exposed, boundaries begin to dissolve.35 Note that the term culture applies to nations, companies, professions, and other identity groups.

The Water Cube team similarly fostered curiosity by bringing people together at several points to talk about design ideas, brainstorm possibilities, and dig into how cultural meanings of design elements differed across nations. Interacting across different cultures was a significant challenge for the team. One technique that worked well was exchanging specialists who had familiarity with both cultures, asking them to go work in the other firm for a period. These literal boundary-spanners helped project members to get interested in each other’s language, norms, practices, and expectations.

Provide Process Guidelines

In any complex teaming effort, it is important to establish process guidelines that everyone agrees to follow. A strategy for boundary management is essential. Guidelines are needed for specifying points at which separate teaming activities must come together to coordinate resources and decisions. Carfrae and his team thus adopted a strategy for “interface management” that divided the project into “volumes” based on physical and temporal boundaries. Each volume was owned by a subteam. An interface existed when anything touched or crossed a boundary. Regular interface coordination meetings were held to manage physical, functional, contractual, and operational boundaries. Through extensive documentation, the team eliminated mistakes that might otherwise occur at these boundaries—saving materials, funds, and headaches.36

Leadership Summary

The complex, interdependent tasks of learning and innovation can no longer be accomplished by a single individual or even by a set of individuals working sequentially (in a hands-off scenario). Whether developing new products, delivering health care, or collecting and processing a nation’s taxes, multiple disciplines and locations increasingly need to work together to get the job done. Teams that succeed today don’t just work around a shared conference table—they collaborate across boundaries of several kinds. But the barriers to teaming across boundaries are often underestimated. In some workplaces, daily face-to-face interactions allow people to talk to each other and share ideas easily. In others, thousands of miles separate those with shared responsibilities, and communicating is more difficult. And borders aren’t the only boundaries that must be crossed when teaming. Occupational, hierarchical, and cultural divisions also exist. Effective teaming, therefore, starts with identifying and acknowledging boundaries.

Diversity gives rise to novel possibilities by combining knowledge across intellectual, functional, and other boundaries. Research has clearly shown that groups and individuals both can learn more when they span boundaries between disciplines and locations. But it’s not easy to do it well. Team leaders and team members must learn to span the boundaries within and between organizations that stifle the flow of information and inhibit collaboration. Fortunately, such ordinary behaviors as asking for help, offering help, expressing curiosity, and voicing interpretations all can work magic in lowering the obstacles to collaboration.

Leaders play an essential role in breaking down the boundaries that impede knowledge sharing and collaboration. Through leadership inclusiveness, the creation of knowledge exchanges, and the use of boundary objects, leaders can increase best practice sharing and innovation. It’s essential to remember that fear in teams where status differences are prominent can hinder communication and sharing. Research finds that psychological safety makes it easier to communicate and experiment across boundaries.37 When organizations create an inclusive environment and master the ability to trade and employ knowledge across organizational boundaries, they can begin implementing a new way of operating called execution-as-learning. Explored in depth in the next part of this book, execution-as-learning is an iterative process that combines continuous learning and improvement with productivity.

LESSONS AND ACTIONS

- People teaming in today’s workplaces are unlikely to be homogenous in beliefs, attitudes, or opinions. When not managed consciously and carefully, these differences can inhibit collaboration.

- The term boundaries refers to both visible and invisible divisions between people, including gender, occupation, or nationality. Boundaries exist based on the taken-for-granted assumptions and diverse mindsets that people hold in different groups.

- Boundary spanning involves deliberate attempts to reach across the barriers that exist within and between groups of all kinds. Rapid developments in technology and the greater emphasis on globalization have greatly increased the significance of boundary spanning in today’s work environment.

- The three most common boundaries confronted in teaming are: physical distance (differences in location), knowledge-based (differences in organization or expertise), and status (differences in hierarchical or professional status).

- Establishing a superordinate goal, fostering curiosity, and providing process guidelines are important leadership actions for promoting good communication across boundaries.

- To overcome geographic boundaries, group members should make periodic visits to other sites, pay close attention to unique local knowledge, and contribute to knowledge repositories and exchanges.

- To overcome knowledge boundaries created by organizational diversity, group members should share individual perspectives, emphasize the value brought by each organization, and establish a collective identity.

- To overcome knowledge boundaries created by occupational diversity, groups should share expertise-based knowledge, establish a collective identity, and use boundary objects, such as drawings, models, and prototypes.

- To overcome hierarchical boundaries and minimizing experienced status gaps, leaders should be inclusive and proactively engage group members in conversation.

Notes

1. F. Rashid, D. Leonard, and A. C. Edmondson, “The 2010 Chilean Mining Rescue (A),” HBS Case No. 412–046 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2010); and F. Rashid, D. Leonard, and A. C. Edmondson, “The 2010 Chilean Mining Rescue (B),” HBS Case No. 412–047 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2010). See also J. Franklin, 33 Men: Inside the Miraculous Survival and Dramatic Rescue of the Chilean Miners (New York: Penguin Group, 2011).

2. R. Robbins, “Quecreek Rescue Still Inspires Wonder.” TRIBLive News, 2007. Available from http://www.pittsburghlive.com/x/pittsburghtrib/news/cityregion/s_519299.html.

3. N. Vanderklippe, “Chile’s CEO Moment,” The Globe and Mail, October 16, 2010.

4. Rashid et al., “The 2010 Chilean Mining Rescue (A)”; Rashid et al., “The 2010 Chilean Mining Rescue (B).”

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Vanderklippe, “Chile’s CEO Moment.”

8. Ibid.

9. A. Morrow, “Fenix: Rocket Ship to Freedom,” The Globe and Mail, October 14, 2010. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/technology/science/fenix-rocket-ship-to-freedom/article1756376/.

10. M. Useem, The Leadership Moment: Nine True Stories of Triumph and Disaster and Their Lessons for Us All (New York: Random House, 1998).

11. D. Dougherty, “Interpretive Barriers to Successful Product Innovation in Large Firms,” Organization Science 3, no. 2 (1992): 179–202.

12. See especially G. Stasser and W. Titus, “Pooling of Unshared Information in Group Decision Making: Biased Information Sampling During Discussion,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 48, no. 6 (1985): 1467–1478.

13. D. A. Harrison and K. J. Klein, “What’s the Difference? Diversity Constructs as Separation, Variety, or Disparity in Organizations,” Academy of Management Review 32, no. 4 (2007): 1200.

14. A. C. Edmondson, “Transformation at the Internal Revenue Service,” HBS Case No. 9–603–010 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2002).

15. I. M. Nembhard and A. C. Edmondson “Making It Safe: The Effects of Leader Inclusiveness and Professional Status on Psychological Safety and Improvement Efforts in Health Care Teams,” Journal of Organizational Behavior 27, no. 7 (2006): 941–966.

16. A. L. Tucker, I. M. Nembhard, and A. C. Edmondson, “Implementing New Practices: An Empirical Study of Organizational Learning in Hospital Intensive Care Units,” Management Science 53, no. 6 (2007): 894–907.

17. See J. R. Detert and A. C. Edmondson, “Implicit Voice Theories: Taken-for-Granted Rules of Self-Censorship at Work,” Academy of Management Journal 54, no. 3 (2011).

18. R. J. Ely and D. A. Thomas, “Cultural Diversity at Work: The Moderating Effects of Work Group Perspectives on Diversity,” Administrative Science Quarterly 46 (2001): 229–273.

19. J. Aronson and C. M. Steele, “Stereotypes and the Fragility of Human Competence, Motivation, and Self-Concept,” in Handbook of Competence & Motivation, ed. C. S. Dweck and E. Elliot (New York: Guilford, 2005).

20. S. L. Gaertner, J. D. Dovidio, J. A. Nier, G. Hodson, and M. Houlette, “Aversive Racism: Bias Without Intention,” in Affirmative Action: Rights and Realities, ed. R. L. Nelson and L. B. Nielson (London: Oxford University Press, 2005).

21. A. C. Edmondson, B. Moingeon, V. Dessain, and D. Jensen, “Global Knowledge Management at Danone (A),” HBS Case No. 608–107 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2007).

22. Ibid.

23. Ibid.

24. B. R. Staats, M. Valentine, and A. C. Edmondson, “Using What We Know: Turning Organizational Knowledge into Team Performance,” HBS Working Paper No. 11–031, 2010.

25. Nembhard and Edmondson, “Making It Safe.”

26. A. Tucker and A. C. Edmondson, “Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center,” HBS Case No. 609–109 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2009), p. 10.

27. Note that this is a pseudonym; for the study, see D. Sole and A. C. Edmondson, “Situated Knowledge and Learning in Dispersed Teams,” British Journal of Management 13 (2002): 17–34.

28. D. Ancona, H. Bresman, and K. Kaeufer, “The Comparative Advantage of X-Teams,” Sloan Management Review 43, no. 3 (2002): 33–39.

29. Sole and Edmondson, “Situated Knowledge.”

30. Tucker and Edmondson, “Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center,” p. 13.

31. P. Carlile, “A Pragmatic View of Knowledge and Boundaries: Boundary Objects in New Product Development,” Organization Science 13, no. 4 (2002): 442–445.

32. B. A. Bechky, “Sharing Meaning Across Occupational Communities: The Transformation of Understanding on a Production Floor,” Organization Science 14, no. 3 (2003): 312–330.

33. B. LePatner, Broken Buildings, Busted Budgets: How to Fix America’s Trillion-Dollar Construction Industry (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007).

34. A. C. Edmondson and F. Rashid, “Integrated Project Delivery at Autodesk, Inc. (A),” HBS Case No. 610–016 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2009). See also A. C. Edmondson and F. Rashid, “Integrated Project Delivery at Autodesk, Inc. (B),” Harvard Business School Supplement No. 610–017, 2009; A. C. Edmondson and F. Rashid, “Integrated Project Delivery at Autodesk, Inc. (B),” Harvard Business School Supplement No. 610–018, 2009; also see F. Rashid and A. C. Edmondson, “Risky Trust: How Multi-Entity Teams Develop Trust in a High Risk Endeavor,” Harvard Business School Working Paper No. 11–089, 2011.

35. E. Schein, Organizational Culture and Leadership, 4th ed. (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2010): pp. 155–176 [chap 21].

36. R. G. Eccles, A. C. Edmondson, and D. Karadzhova, “Arup: Building the Water Cube,” HBS Case No. 410–054 (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2010).

37. See C. B. Gibson and S. G. Cohen, Virtual Teams That Work: Creating Conditions for Virtual Team Effectiveness (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2003). See also Sole and Edmondson, “Situated Knowledge”; and A. C. Edmondson, “A Safe Harbor: Social Psychological Factors Affecting Boundary Spanning in Work Teams,” in Research on Groups and Teams, eds. B. Mannix, M. Neale, and R. Wageman (Greenwich, CT: Jai Press, 1999).