4

Who does what in television news

If television news is a jigsaw puzzle, then most of the pieces represent highly skilled technicians with special contributions to make towards building up the final picture. For in modern industrial jargon television remains ‘labour-intensive’ which, despite the frequent trimming of staff numbers, means that a large percentage of what it costs to run such an organization is spent on the wages bill. Value for money is therefore essential.

Purely local broadcasting, frequently run on a tight budget, has always demanded nothing if not versatility from its people. In its mildest form this has been likely to give an executive senior managerial and administrative duties as well as editorial ones, an engineer responsibility for operating a television camera in the studio one day, a videotape recording machine in the newsroom the next, and a portable recorder on location the day after – or all three within hours. A journalist may have the task of combining news-gathering with news processing. In extremes this versatility requires reporters to edit some of their own pictures as part of a normal day’s work and camera-operators to write commentaries for some of their own material. Journalists may also be expected to rotate between radio, television and text or online news services.

National news programmes, too, are not necessarily free of the need to be economical in their use of staff resources. One senior news editor in the Caribbean used to spend the first two-thirds of the day as a reporter and writer for the main evening news and the remaining third in the studio directing the cameras for the same newscast. It is not many years since a western European television news service operated without any permanent journalistic staff at all, apart from the chief editor. The writing for the main bulletins was undertaken by journalists who had already completed a full day’s work elsewhere. Even among the more fortunate it was – and still is – not uncommon for television news to have to share such basic services as camera crews, picture editors, equipment and transport with sister departments within the same organization, even though obvious problems arise from the need to serve one master.

At the other end of the scale, the big national networks in television news usually have exclusive use of their own separate staff, studios and technical equipment. For example, the BBC operation is housed in its own wing of the News Centre, part of Television Centre in west London, but remains part of a public corporation responsible for a vast range of television and radio output. Independent Television News, with headquarters in Gray’s Inn Road, is now owned mainly by a consortium of television companies to whom it supplies daily national news programmes for the ITV network, Channel 4 and Channel 5. Sky News is part of British Sky Broadcasting, delivering news 24 hours a day by satellite and cable to audiences in Britain and abroad.

Figure 4.1 Premises that have been purpose-built for news broadcasting organizations. (a) ITN’s building in central London. (Photo courtesy of Wordsearch, Alan Williams); (b) The BBC News Centre is attached to the original Television Centre.

Multimedia working and multi-skilling

Chiefly because of the demands on them to produce programmes at least three or four times a day or, in the case of the all-news channels, continuously, the ‘big league’ news organizations each need full-time staffs totalling several hundred. These are divided into smaller groups of specialists – camera-operators, reporters, picture editors, studio directors, graphics designers, newsroom journalists and so on, who have traditionally rarely strayed from a limited number of clearly defined duties. But changes are taking place under the influence of economic stringency, allied to increased competition. ‘Multimedia working’ has been heavily encouraged by employers anxious to maximize their human resources, and the drive towards newsrooms staffed by people expert in several disciplines has continued apace. Multimedia offices, with radio, text, online and television operating together, now exist in many BBC regions and within the substantial political and parliamentary unit near the Palace of Westminster.

Much the same approach is behind the move towards ‘multi-skilling’, the aim of which is to make use of what are called ‘adjacent skills’. So, for example, reporters on location are encouraged to work microphones, picture editors learn to write, newsroom-based journalists are tutored in picture editing. The idea of an entirely multi-skilled, multimedia team is a very attractive one for employers seeking a flexible workforce, while for some workers the breaking down of the strict demarcation lines which sealed them into a range of useful yet often repetitive or mechanical jobs has been warmly welcomed.

Even some of the diehards recognize the logic of having one journalist covering a story for both radio and television, but point to the likelihood of being so busy meeting a string of deadlines that they have little time to exercise their news-gathering skills. Getting to the story, they complain, has almost become of secondary importance.

Other critics believe multimedia and multi-skilling are devices aimed principally at cutting costs and that in the long run the effect will be to damage hard-won craft standards. The trades unions involved in broadcasting are particularly suspicious of employers’ motives and monitor them with an eye on the details of rotas, working hours and management behaviour. The unions were particularly worried about the Burn Out Factor. It was not so much a case of worrying about the news-gathering ability of a person who is required to shoot, write, and edit a story, but for how long that person can do it without his or her health suffering, alongside the problem of the quality of the final material. Many broadcasting managers started to realize towards the end of the 1990s that perhaps it was a bit much to ask at a time when the jury was out on pioneering late-1990s’ digital technology. In general, journalists who had already mastered writing skills took much better to using the camera than they did to editing the vision and sound. Multi-skilling had started to settle in job ‘families’ (shoot–write or shoot–edit or edit–write or edit–direct) which provided a more stable approach to getting the news on air.

The organization of television news

With the advent of multi-skilling and bi-media working, the existence of any ‘traditional’ organizational structure within television news has come to take on even less meaning than it may ever have done in the past. Working practices vary widely across the world – sometimes within different parts of the same company – and the nuances of operation are such that a common language covering job titles and editorial/production methods has never satisfactorily taken root, glossaries notwithstanding.

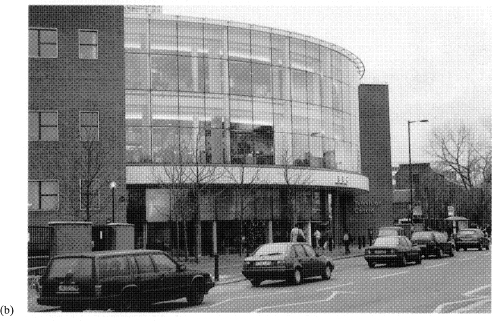

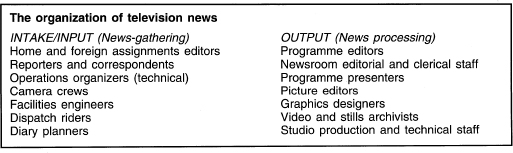

That said, there is a similarity between many of the big organizations, which have functioned successfully for years by establishing a clear division of responsibility between those who gather the raw material for news (intake or input or news-gathering) and those who process and shape it for transmission (output), staffing the structure accordingly. This puts reporters and camera crews into the former category and newsroom-based journalists and production staff into the latter.

Operationally, both sides of the editorial machine are notionally under the control of the most senior output people on duty – usually the editors of the daily programmes. At one time it was fashionable to give responsibility for each day’s news coverage, treatment and output to a single person known as ‘editor for the day’, the main benefit being seen as the continuity it provided, for each editor’s spell on duty was 12 hours or more covering the transmission of several (shortish) news bulletins.

Editors for the day (more accurately, editors for part of the day) still exist in some all-news channels, and may control strands such as hourly summaries, but the current view generally acknowledges that it is virtually impossible for anyone to take charge of more than one main newscast a day, because programmes are longer, technically more difficult, and differ in style and content from others within the same stable. In any case, goes the argument, there would be scarcely enough time to give proper consideration to one newscast before the next one became due. So even though they may be sharing some staff and facilities, the editors of programmes within the same organization are usually working towards separate goals.

Aside from operational duties on the day, the editor of a news programme within the intake–output system also has to shoulder a degree of responsibility for anticipating what will appear on the screen. Lengthy planning meetings are held daily, weekly and monthly, at which the meticulously compiled diaries are considered event by event under the guidance of the domestic and foreign news executives whose job it is to deal with the logistics of news coverage for the whole of the output.

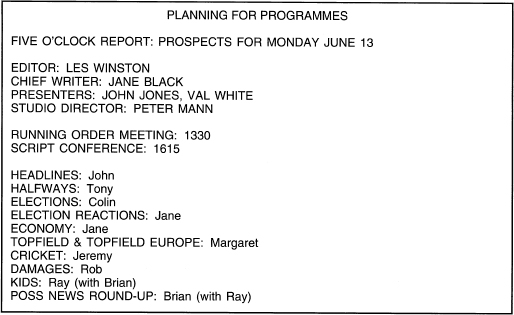

Figure 4.2 Typical division of responsibilities in a large news organization, with one group of people concentrating on news-gathering, the other on news processing and production. Many roles are combined in smaller news organizations.

Figure 4.3 Progress of news items. Note the importance of the home/foreign assignments desks as the chief link between incoming sources and the output editorial and production teams. In some news services the role of writer/producer may be combined with picture editor.

At this stage each editor is really gazing into the crystal ball, trying to foretell what the programme on his or her next duty day will in part contain, even though it is clearly understood by all concerned that the most expensive, carefully-laid plans will be scrapped at the last moment should a really important story break unexpectedly. It is a hazard readily accepted by everyone, not least by those who may have spent many hours setting up interviews or obtaining permission to cover news items which may never be seen.

Such flexibility is a routine but essential part of the news-gathering process, which is relatively slow under even the most favourable conditions, although the speed of communication has improved considerably.

It has long been recognized that coverage for factual television programmes has to be organized well in advance to ensure that people and equipment are properly positioned as an event takes place. To that extent it is far simpler to call off coverage than it is to lay it on at the last moment.

At the sharp end of news-gathering are the journalists and camera teams, the troops ultimately responsible for providing much of the raw material. The reporters and correspondents ‘get the story’, conduct the interviews and do pieces-to-camera, while the technicalities are carried out by the camera crews. It is in this area that some of the most radical changes in television news have taken place. The introduction of very lightweight video cameras using cassettes which combine picture and sound has virtually ended the practice of two-man crewing. Camera-operators work alone, except for those increasingly rare occasions which necessitate separate sound recordists. A few lighting technicians/electricians also still exist in news, but their work is confined to those rare events which call for more artificial light than that carried routinely by the camera-operators.

The main responsibility for arranging news coverage eventually rests with the duty news editor or news organizer1 staffing the home assignments desk as the mainstay of that part of the operation dealing with domestic subjects. With these journalists, through the programme editors and department heads, rest the moment-to-moment decisions of when to dispatch staff reporters and camera teams on assignments, or when to rely on regional or freelance effort to produce the goods. The news organizers often see themselves, somewhat cynically, as the ‘can-carriers’ for news departments, being criticized when things go wrong but rarely being praised for success. News organizers are meant to have the mental agility of chess grandmasters in moving pieces (in this case reporters and crews) into position before events occur, at the same time making sure that enough human resources remain available in reserve to deal with any important new events which may arise.

The work also demands a certain intuition about the workings of senior colleagues’ minds. In briefing reporters, for example, they are expected to know instinctively how any one editor would wish an assignment to be carried out, down to the detail of questions to be asked in interviews. The role of the news organizer/editor is generally restricted to arranging on-the-day coverage, much of which is based on plans previously laid by other members of the department.

The duties of the planners include the submission of ideas for, and treatment of, the various items. But the routine calls chiefly for a well-developed news sense. This must be keen enough to isolate a tiny residue of screenworthy material from an overwhelming array of incoming information on subjects of potential interest. Much planning time is spent ‘phone bashing’, calling to arrange interviews, to verify whether what seems interesting on paper will actually stand up to the closer scrutiny of a camera, and to evaluate whether the various ingredients, as discussed, are likely to result in a clear and balanced report eventually being transmitted. Once the broad details have been agreed, each item, now formalized under a one- or two-word code name it will keep until it reaches the screen, is added to the internally circulated list of subjects for prospective coverage. At a still later stage, arrangements may have to be made to collect any useful documents or special passes needed on the day, so that the process of collecting the news may be carried out as smoothly as possible.

Planning for longer-term or particularly complicated assignments may well be conducted by special units created within the news-gathering department on a permanent or ad hoc basis. Big set-piece events such as summit meetings, elections, party political gatherings or any coverage destined to last several days, call for highly detailed organization in advance if the eventual reportage is to be comprehensive. It may be necessary to establish temporary headquarters away from base, committing substantial numbers of staff and technical resources to ensure that the main story and any side issues are properly covered.

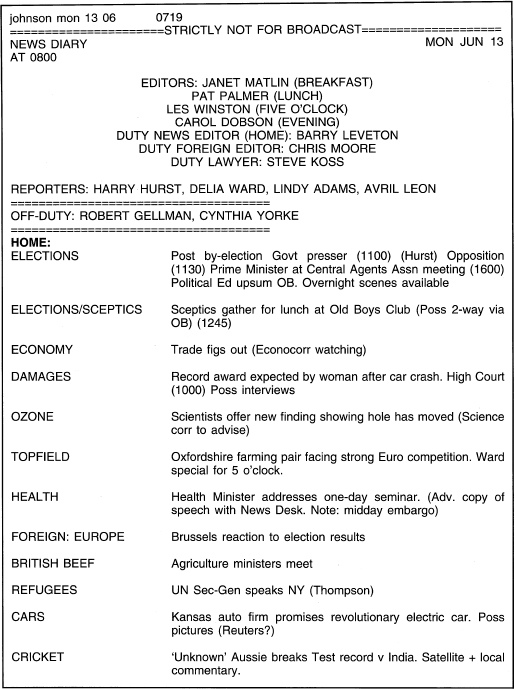

Figure 4.4 An example of daily home and foreign news prospects for a series of national programmes. This list of events for coverage is distilled by the planners from a wide range of possible stories for editors to consider.

Figure 4.5 In addition to the main prospects prepared and discussed at a daily editorial meeting, each programme team may compile its own as first confirmation of the main stories being covered, together with the allocation of the editorial team members to write and produce them. Knowing who is responsible for what makes collaboration easy for production and technical staff as progress is made towards transmission. The prospects will be made available on everyone’s computer screens.

The spin-off from all this effort may well be extended reports within the regular news programme, continuous coverage, or specials in their own right.

The same units may also be responsible for preparing background items and for keeping the profiles/obituaries of prominent personalities up to date – in fact for almost anything that helps programme editors avoid an unsatisfactory scramble to get something on the air.

Working in close harmony with the rest of the news-gathering department are the staff concerned with the technical side. An executive, variously named field operations organizer, assignments editor/manager, or camera unit manager works out rosters for the camera crews to go about their duties with or without reporters, probably keeping in touch by means of two-way radio telephone systems installed at base and in the camera vehicles. The executive’s empire probably also includes the FACS (facilities) staff, engineers whose role is to supply the communications links between base and the camera crews on the road.

Other members of the intake team are likely to include clerks, whose duties involve booking studio time and facilities for material originating from regional and other outside sources, plus a small posse of motor cyclists who play an indispensable part in the collection of videotapes and still photographs.

Foreign news departments may have a small presence at base but this is the tip of a formidable iceberg made up of staff correspondents resident abroad, a world-wide network of stringers, and close ties with friendly broadcasting organizations able to conjure words and pictures from virtually anywhere in the world at very short notice.

The department is probably headed by a foreign news editor/foreign assignment editor, a senior journalist whose skill at balancing the books is becoming as big an asset as a sure editorial touch. Duties for foreign editors are likely to extend beyond company boundaries into a profusion of contacts with other broadcasters and the multinational ‘clubs’ established to provide regular, free-flowing exchanges of news material.

The routine administrative load is shared by deputy or assistant foreign editors, while operationally the better-off can afford to staff the foreign assignments desk with two or three foreign duty editors, working in rotation. These are the equivalent of the news organizers on the domestic side, providing a link between the news-gatherers in the field and programme editors at home. The dispatch of normally home-based staff on ‘fire-brigade’ assignments is a matter for negotiation between the more senior members of the department.

The last link in the foreign chain is the foreign traffic manager, or satellite operations organizer, who makes the detailed arrangements for the collection of material from abroad, and who needs to be in frequent direct contact with other broadcasting organizations, especially during the regular conferences between ‘club’ members. The residents of the foreign traffic desk are also renowned for their encyclopaedic knowledge of the procedures for organizing satellite communications at very short notice – a talent in demand when important news breaks at awkward times in some of the world’s most unexpected places.

Despite the phenomenal growth of news-gathering operations over recent years, television news output among the international players remains bigger and more complicated, encompassing as it does three services functioning within the loose categories of editorial, production and technical.

Among the craftspeople who work in these three areas lies the same sort of generally friendly rivalry which exists between a newspaper’s journalists, advertising staff and printers. But, however much they may grumble about a perceived lack of appreciation, rates of pay and working conditions compared with the others, all are acutely aware of the fact that no single group’s skills are by themselves sufficient to transform the material produced by intake into coherent television news programmes.

Much the same can be said for smaller-scale or differently structured programmes or services which, however organized, face similar processes in getting their product on to the screen.

The mechanics of editorial decision-making obviously differ from programme to programme. Logic suggests that policy is likely to be dictated by executives who are higher up the hierarchy and are expected to be in tune with the political, financial and commercial interests of the organization as a whole. This reflects the degree of autonomy delegated to the editor/producer, the senior member of the team responsible operationally for one newscast or other segment of airtime. Some editors are left entirely to their own devices (with the encouragement to refer contentious issues upwards) while bureaucracy confines others to work within more restricted limits. For these, mandatory attendance at regular editorial meetings chaired by executives not pressured by deadlines can be a frustrating and time-consuming diversion from other important duties.

Most programme editors are happiest away from their offices, preferring to base themselves in the newsroom where communications are most easily maintained. According to personal style, each editor exerts a different amount of influence to ensure that the programme follows its intended course. Computer terminals and television screens on their desk enable them to monitor the progress of coverage in the field and in the editing process, but much of the time is taken up with matters of detail affecting such things as content, construction, treatment, legal matters, taste and decency.

Figure 4.6 Television news organization chart. How a typical system might be structured. Hierarchies will differ, but in this example there is an Editor-in-chief responsible for all output to one or a number of senior executives. Administration, including staffing and finance, is carried out separately, while the day-to-day journalistic management is conducted under the overall guidance of a managing editor.

Marshalling the rest of the staff and assigning stories to individual writers may also be part of the editor’s duties. Many are also expected to be the sole filter of raw material for broadcast as well as writing scripts of their own, assessing and checking the work of others and ensuring overall duration is within the allotted time span. A lot of attention is paid to the headlines at the top of the bulletin, not just the words but the images and sound that are needed to encourage the viewer to watch the rest.

Thinking time is at a premium for such busy people, and with so many calls upon an editor’s time, and with so many loose ends to be tied during an often hectic few hours, responsibility for the detailed organization of a programme is likely to be led by a senior lieutenant. Titles vary, assistant editor/senior production journalist/senior broadcast journalist.

Although the chief’s responsibilities may include some writing – perhaps the headline sequence, if there is one – the most important aspects of their work are likely to be as much managerial and administrative, with the accent on quality control and timekeeping.

Quality control begins with the briefing of the newsroom writing staff, perhaps six or eight people of different seniority, who are preparing the individual elements within the programme framework. It continues with the checking of every written item as completed so all the strands knit together in a way which maintains continuity while avoiding repetition, and language and programme style are kept on an even keel throughout. This may mean striking out or altering phrases, perhaps even rewriting entire items composed in haste by people working under intense pressure. Faster moving continuous news services do not always have that luxury and many items written by one journalist are never read by anyone else until they reach the presenter in the studio.

Also, as a journalist of great experience, the senior editor has further value as an editorial long-stop, preventing factual errors creeping through in a way which would ultimately damage the credibility of the entire programme.

Unlike continuous news services, such as Sky, CNN and BBC News 24, scheduled television news programmes (although agile when they need to handle a big breaking story) are rarely open-ended. They need to have a ‘junction’ with the next programme in the schedules. The senior journalist’s talents are meant to include a facility for speedy and accurate mental arithmetic, essential for the other part of the role of time-keeper. Steering a whole programme towards its strict time allocation is no mean feat, especially as so much depends on intuition or sheer guesswork about the duration of segments which may not be completed until the programme is already on the air.

For these reasons the chief continually has to exhort those entrusted with individual items to restrict themselves to the space they have been given. A typical half-hour news programme might contain twelve or more separate elements varying in importance and length. An unexpected 10 or 15 seconds on each would play havoc with all previous calculations, resulting in wholesale cuts and alterations. These in turn would probably ruin any attempts to produce a rounded, well-balanced programme.

A further stage in the senior editor’s time-keeping duties comes during transmission itself, when the appearance of late news may call for instant decisions on where to cut back. This means deleting material to ensure that, whatever changes have to be made for editorial reasons, the programme does not overrun its allocation of airtime, even by a few seconds.

Computer news processing systems can provide instant recalculations on programme duration, adding up not just the duration of pre-recorded reports, but also live reports that have just taken place and the duration of the links read by the presenter. Newsroom computer systems are now able to deal easily with all manner of arithmetical calculation, including late additions, subtractions, or wholesale changes to the order of transmission (see pp. 40-42).

The journalist newcomer to television news may expect to join the newsroom’s pool of writing staff, usually the largest single group within the editorial side of output.

As the main link between news-gathering and the production and technical areas, writers exert considerable influence over what the viewer eventually sees on the air, substantial changes in their roles and responsibilities over the years keeping pace with variations in the style and content of the news programmes they serve.

These changes have been reflected in the different titles they have been given in the past, among them sub-editors, scriptwriters, news assistants, news writers and producers, the prefix ‘senior’ or ‘chief’ being added where ranking exists. Multimedia working has led to the introduction of the generic term broadcast journalist, denoting responsibility across radio, television and online or broadcast text services. On local stations especially, their work is almost sure to include intake duties, including the assigning of reporters and camera crews. Some may also appear on screen and in front of the microphone.

Such variations make it impossible to be precise about what writers do in every case, so the following description should be taken to apply in the most general terms. Within the limits of responsibility as defined by their job descriptions, writers/producers assemble the components which make up every programme item – selecting still photographs, graphics, artwork and videotape, writing commentaries and liaising closely with contributing reporters and correspondents. The most senior are often put in charge of small teams of other writers to compile larger programme segments from particularly complex news items made up of different elements.

What can also be said is that the complexities of modern television production are such that many writers find themselves with little time to devote to the actual business of writing, leaving it to their reporter and presenter colleagues.

Some writers go on to develop expertise in other areas of television technique and, as a result, are occasionally called upon to display their talents as field-producers, directors, or reporters on the screen.

In the busiest or more fully staffed newsrooms, other output duties may be assigned separately, whether or not they are recognised with formal titles. Where a programme uses electronically generated artwork a graphics producer may coordinate commissions and oversee progress until transmission; the responsibility of keeping track of the content and quality of moving pictures flooding in via satellite and from other sources may be delegated to a duty editor. While neither task (nor similar ones) may be considered strictly editorial, television journalists will argue strongly that, for example, the accuracy of spelling cannot be left entirely to a graphics designer, nor the news value of pictures decided solely by a picture editor.

Until the late 1970s it scarcely seemed possible to imagine the world’s television news organizations exchanging their trusted old 16 mm sound cameras and fast-process colour film for lightweight electronic hardware and magnetic videotape. But they embraced the technological revolution with enthusiasm when it came and swept film aside in an astonishingly short time. At a slightly slower pace, digital cameras, editing and transmission systems started to replace electronic news-gathering and production during the late 1990s. Beyond 2000, digital is the norm: fast, light, cheap, mostly easy to use and in some cases disposable. The technology had a short infancy. Many senior news executives however will use the maxim Content is All – meaning that no matter what technology is used, it is that final material that comes out of the TV set or goes into your website that matters. Rubbish is always rubbish. The good stuff is always good. Don’t blame the equipment.

Film editors, for example, became picture editors, adapting their skills to continue working closely with the writers from the newsroom, viewing and assembling the raw video material into coherent story lines within lengths dictated by their programme editors. Edited picture stories may run for a few seconds or several minutes, according to importance and, as with the editorial side, the more experienced are given the most complicated items to assemble. The junior staff handle those involving simple editing of minor stories (which may never get on the air) and material copied from the archives.

In the leading news services picture editors may expect to be allocated their work and generally supervised by senior colleagues with deadlines in mind. Other production staff are closely concerned with the operation of the studio control room, the central point through which all newscasts are routed.

The main occupants of the studio area (whether an integral part of the newsroom or a separate facility) are the newsreaders/presenters/anchors, the faces on whom the success or failure of any news service may be said to depend. Although reading other people’s written work aloud for limited periods each day might not seem either particularly onerous or intellectually demanding, consistently high standards of news reading are not easily reached, and there are other pressures to offset the undoubted glamour of the job. In many ways the news presenter is well paid because he or she is supposed to be able to cope when things go wrong. They often do, and with very experienced presenters the viewer may never ever know it. Many of those with strong journalistic backgrounds are also closely identified with their programmes, to the extent that they now have a role in the decision-making as well as writing a large part of their own material.

In front of the presenter are between three and five cameras providing the link with the viewing audience. Many studios have robotic cameras operated from the control room which move to and from pre-programmed fixed points on the studio floor.

Although responsibility for the technical quality of the television signals being transmitted rests with a senior engineer, sometimes called the technical coordinator or transmission manager, the creative head of the control room on transmission is the studio director, who coordinates all the resources offered by the three areas of output. Helping fuse these together at the critical moment is a vision mixer to implement the director’s selection of pictures from studio or other sources as defined by the script; and a sound operator/engineer to bring in the accompanying audio signals from microphones, recordings and additional soundtracks, etc. Slight errors or delays in reaction by any member of this team are instantly translated into noticeable flaws on the screen.

Several other creative groups may come within the category of production. Graphics designers/artists are engaged full-time on the provision, in accepted ‘house’ style, of all artwork used in television news. The software used by graphics is sophisticated, providing maps, charts, diagrams and the names of people appearing on the screen. The graphics computers can provide millions of colour combinations, more than the human eye could separate. Stills/picture assistants research and maintain a permanent, expanding library of photographic prints and slides, some of which are taken by staff photographers assigned to supplement material provided by freelances and the international agencies. Other librarians/archivists are responsible for keeping and cataloguing a selection of transmitted and untransmitted picture material. Newspaper and other print material are kept on computer files, although many older copied cuttings are still available.

On a daily basis the technical staff are directly responsible for the maintenance and operation of both electronic equipment and complex computer systems. Their first aim is to ensure the highest possible technical standards, but at the same time to remain flexible in outlook, for compromise is often necessary where picture and sound material may be poor in quality but high in news value.

Engineering staff are also the mainstays of any number of units capable of transmitting news material directly back to base from outside locations. Links vehicles, fast response vehicles or satellite news-gathering systems are scaled-down versions of the multi-camera outside broadcast units used for the coverage of major events, and are integral to the process of news-gathering in an increasingly competitive environment.

Engineering tasks, though rarely sharing the limelight, are nevertheless central to the existence of any programme. Without them, and all the clerks, secretaries and other support staff working across the organization, the carefully constructed jigsaw puzzle of television news would fall apart.

The argument against the intake–output system is that it is often the tail wagging the dog, concentrating too much power in the hands of the planners, who make most of the serious decisions about coverage, especially at times when money is tight. Editors often feel under pressure to use material which has been gathered at some expense, especially from abroad, even though their instinct tells them otherwise. Considerable financial responsibility goes with the coverage of any editorial ‘patch’.

At the other end of the scale, modern integrated newsroom systems confine the decision-making process to smaller numbers. The editors in charge involve themselves as much in the detailed planning of coverage as in the eventual newscast for which they are responsible, and in some local US news stations still double as correspondents or anchors. Elsewhere, the editor may be that in name only, with authority stretching barely beyond the compilation of the running order.

The categories of non-broadcasting producer or writer may not exist, with every member of the editorial team considered a reporter, whether general or limited to foreign news, domestic, sport or other specialisms. Duties cover the whole spectrum of research, location reporting, picture-editing supervision and writing. In contrast to practices elsewhere (particularly in the United States, where scripts for national news programmes often undergo rigorous fact-checking and editorial approval processes before they are allowed on air), reporters are likely to have sole responsibility for content, treatment, script and duration. There is no consultation and supervision does not exist. They are allowed to be possessive about their material, and if they harbour any doubts about a particular aspect they will almost certainly discuss them with another reporter friend and not lose face by going to the editor.

Back in the 1980s, during the early days of their emergence from the Communist bloc, reporters from a particular country’s television news service more or less chose their assignments for themselves. And although they were not strictly freelances, they were paid on the basis of what appeared on screen each night. In that currency two or three minor items of thirty seconds duration were worth more than a substantial report which took two or three days to compile. In this atmosphere, with the journalists keeping their own archive materials locked away for possible future use, the idea of professional teamwork and cooperation for the collective good was not exactly top of the agenda.

Although economics inevitably dictate the way a television newsroom is organized, the preferred layout for most continues to be open plan, a design thought to contribute more towards team spirit than a series of separate offices. Executives and some correspondents might be happier working away in complete or semi-privacy, but many journalists thrive on the buzz generated by a busy newsroom environment, and are prepared to put up with limited individual working space, noise and other distractions they would not tolerate in their personal lives.

Much careful thought goes into working arrangements, down to the exact positioning of workstations and the equipment to go on them. The development of multimedia duties, the relationship between the news-in and news-out parts, and the proximity of other areas of the operation, are seen as crucial to efficiency, especially when the newsroom also provides the background for news summaries or complete newscasts.

Computer technology began to replace the smell of ink and the clash of metal back in the 1980s. It started with word and news wire processing. Now computers are not only processing the scripts, but also aiding the editing of sound and vision and actually transmitting the entire programme.

Early systems concentrated on two main areas: the storage of incoming news agency wire stories for writers who were able to retrieve them with a couple of keystrokes, and then the use of the computer’s word-processing facilities for scriptwriting, printing and collation. Running order composition and timing, reporter and camera crew assignments, duty rosters, news diaries and a host of other uses were added until the computer became an indispensable and integral part of news programme production.

Anyone familiar with the operation of almost any personal computer should be able to adapt easily to the demands of networked systems in which probably every occupant of a newsroom has access to a terminal.

Basic refinements include the ability to transform draft script pages into accepted programme format; a split screen, allowing wire copy to be retrieved on one side while a script is written on the other; automated calculation of script and programme duration, and access to archive material. Advances have also been made in split screens which incorporate moving pictures as well as text, while even greater scope exists for the establishment of links with the process of programme production and desktop editing.

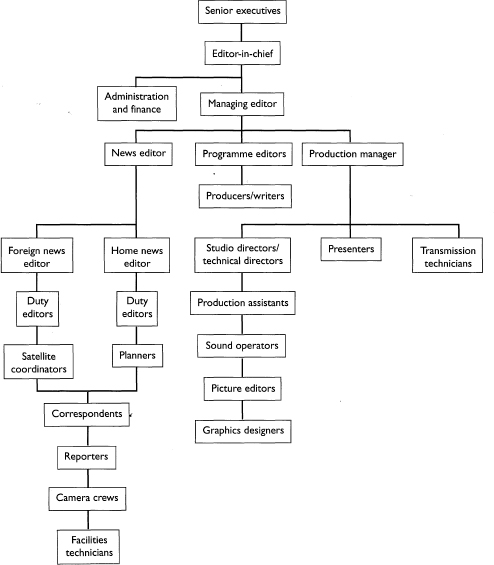

Figure 4.7 The computerized newsroom. Assignments, running orders, archives and many other functions are available to each and every journalist and member of the production team at the same time. Desktop editing of sound and vision also speeds the process of moving news from the news-gathering stage to its transmission. (Photo courtesy of and © Sky Television.)

For some time now it has been possible for scripts written in the newsroom to be read in the studio from cameras fitted with electronic prompting attachments. Using the later generation of newsroom computer systems, journalists are now able to compose simple graphics while sitting at their terminals and to insert instructions to operate stills stores and video inserts. The electronic news systems being used by most newsrooms now have menu displays, editing and powerful search facilities to enable the journalist to hunt a word or word combination, or to download all the scripts about a particular story.

One of the main benefits of the newsroom computer is its ability to cope with changes ranging from the smallest detail in a single script to the wholesale recasting of programmes. Amendments, additions and subtractions can be considered, entered and previewed at leisure, then executed in a twinkling. Running orders and completed scripts are available to everyone who is in sight of a terminal, at once. As long as the computer is programmed to tell the master printer the chosen final order, scripts for an entire newscast, of whatever duration, will be printed out in the correct sequence, and will be followed automatically by the electronic prompter.

Programme timing, too, becomes much simpler. The computer not only calculates the time taken up by each component of every script in a running order, it adds to the overall duration, remembering to adjust when new stories are added and others dropped, all the time taking account of a reader’s individual reading speed.

Terminals sited in the studio control room remove the guesswork and arithmetical contortions from the process of transmission. As the broadcast progresses, the computer takes account of those items which have gone and those which remain to be transmitted, making minor adjustments to ensure that the programme ending on time is a simple matter for editorial staff.

For assignment desks, details of diary events and forthcoming coverage are entered by news planners and stored for retrieval by producers, reporters and camera crews when they come on duty. In the field, out-stations and overseas bureaux, laptops and desktops are available for reporters to write scripts and transmit them to base. The whole news process has been speeded up in a way never thought possible.

There may of course be a downside to all this. Getting out of a chair to indulge in conversation at the other end of a big newsroom may be considered unnecessary when it is so much easier to spend a few seconds in front of the electronic message-sender. Certainly there are many occasions when this will be a reasonable action to take, but care must also be taken to ensure that the habit of human contact between professional colleagues is not lost.

‘Scripting’, so much simpler using a word-processor, must not become a purely ‘written’ process, heralding a departure from the conversational style so crucial to broadcasting: writers who many years ago used to dictate their work aloud to typists became aware immediately if what they had composed ‘sounded’ wrong.

Another aspect to be considered is that health and safety managers must ensure that furniture and lighting are compatible with continual computer usage – some people complain of eyestrain, headaches and backache, as well as RSI (repetitive strain injury).

And the history of the future …

History is a recycling of persistent truths. The journalist of 2001 and beyond is still faced with the same human-sized challenge as the journalist on a newspaper a century ago, long before even television news was invented. That is Garbage In, Garbage Out, or WYSIWYG (whizzywig). This means: What You See Is What You Get! What the journalist puts into the PC is what comes out in the viewers’ faces, whether it is a bad script, bad editing, spelling errors on graphics or a keystroke hit in error which moves a story item to the wrong end of a bulletin. As mentioned earlier, Content is All. The computer won’t write it for you and writing skills remain part of the human factor. Computers never make mistakes. They are machines. The most sophisticated computer system is not as complex as a single human brain and never as creative. Only people make mistakes, whether it is the people who write the computer programming, or the journalist who writes the news.

1. These are operational titles. Broadcasting organizations have different titles for similar posts.