The rules of the game have changed

In 1992, Jack Stack, President and CEO of Springfield Remanufacturing Company in Springfield, Missouri, wrote an award-winning book with Bo Burlington, Editor-at-Large with Inc. Magazine. The book was titled The Great Game of Business: Unlocking the Power and Profitability of Open-Book Management. In it, the authors describe a management process that they used to turn their manufacturing business around, during a period of very difficult times in their industries. They used the analogy of ‘business as a game’, based upon the concept that in any game, people keep score, so that they know how they are doing. Stack’s premise was that if you are keeping financial records, then you are keeping score.1 What business does not keep financial records? The dilemma occurs when you want your staff to be ‘in the game’ with you, but you don’t ‘share the score’ with them. In Stack’s approach to ‘Open- Book Management’ every employee is taught how to read, understand and contribute to the data collection needed to ensure everyone knows what the score is at all times so that they can then decide what they individually and collectively can do to help the team to ‘win the game’.

While our book is focused on Human Resource Management practices, more so than ‘participative management practices’, as profiled in Stack and Burlington’s book, there is a connection that we have found very useful. The use of the game metaphor helps us to think about the ‘business of human resource management’ from the perspective of a game. We know that a sports metaphor does not appeal to everyone, but bear with us. We are using it only to create a framework for thinking about how to become a winner in the area of human resource management.

In every game there are a few fundamentals that are always present. These include:

![]() The Point of the Game – What are we trying to achieve and why are we playing this game?

The Point of the Game – What are we trying to achieve and why are we playing this game?

![]() The Rules of the Game – Those things that every player must do or must not do, to ensure that the game is played fairly and one player or team does not obtain an unfair advantage over the other player or team.

The Rules of the Game – Those things that every player must do or must not do, to ensure that the game is played fairly and one player or team does not obtain an unfair advantage over the other player or team.

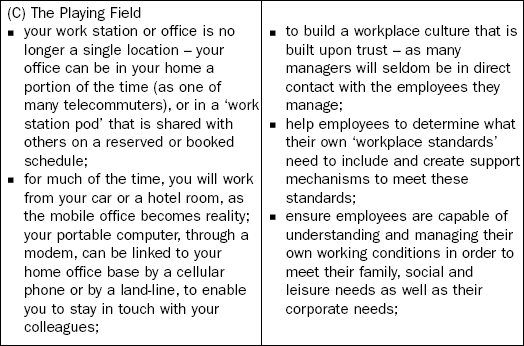

![]() The Playing Field – The ‘field of play’ or the boundaries within which the game is carried out.

The Playing Field – The ‘field of play’ or the boundaries within which the game is carried out.

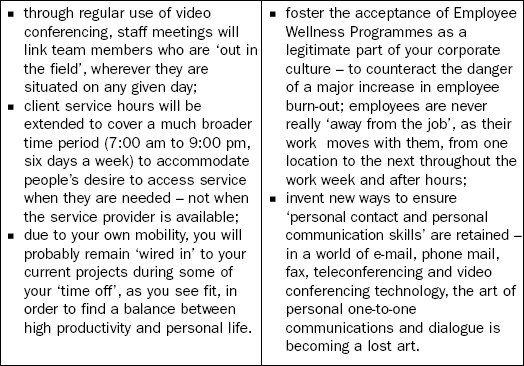

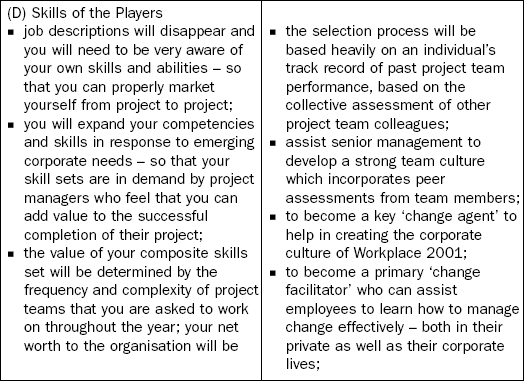

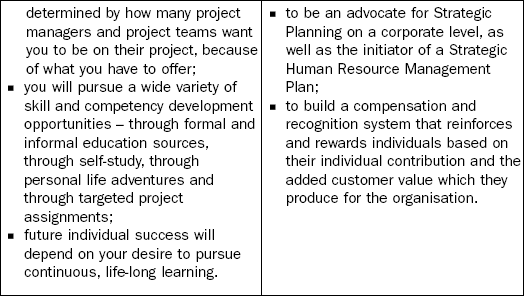

![]() The Skills of the Players – The technical skills needed to be proficient at the sport in question. It also includes the skills of being a good, contributing team member, if the sport involves more than one player. It also includes the characteristics of being a good sportsperson, participating in a fair and ethical way.

The Skills of the Players – The technical skills needed to be proficient at the sport in question. It also includes the skills of being a good, contributing team member, if the sport involves more than one player. It also includes the characteristics of being a good sportsperson, participating in a fair and ethical way.

Regardless of the game being played, whether it is football, basketball, scrabble or bridge, these characteristics will always be present. These same characteristics can be used to examine the ‘game of human resource management’.

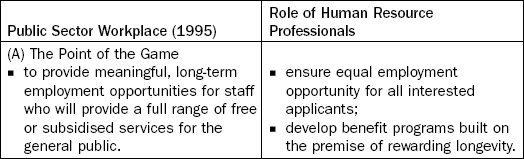

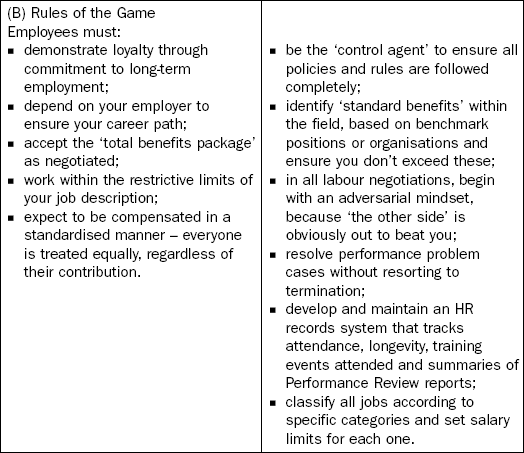

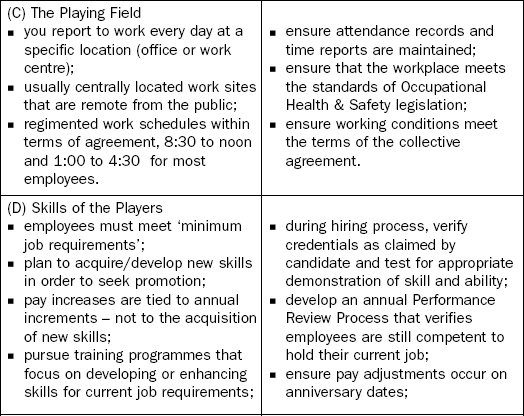

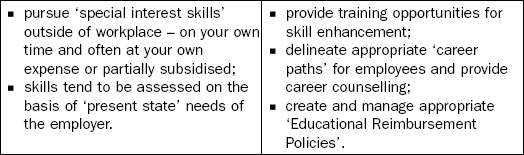

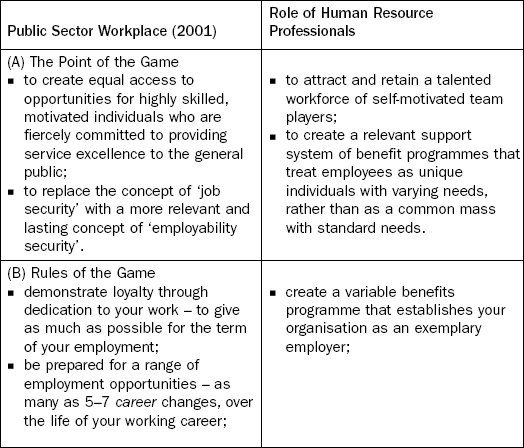

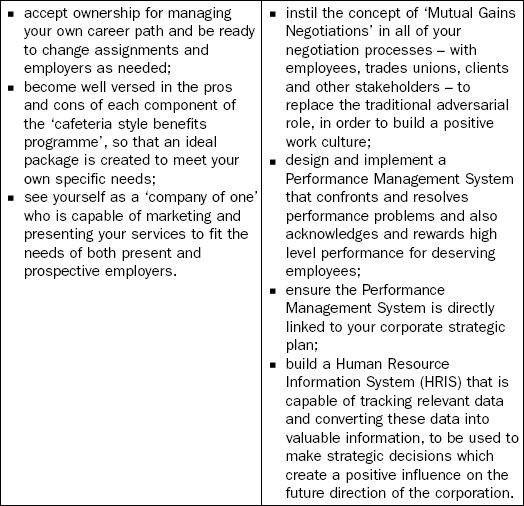

In 1995, in an effort to apply this concept of the ‘game of business’ for a group of HR professionals who worked with Canadian public sector organisations, we created a breakdown of what the New Game of Human Resource Management would look like between the years 1995 and 2001, which represented that magical ‘turn of the century’ moment that we had been anticipating for so many years. Now that we have passed through that historic time frame, it is interesting to note that many of the proposals put forward in the presentation that was made to these HR professionals at a Western Canadian Cities Conference held in Edmonton in 1995 are still relevant.

The following two tables outline what the game looked like for public- sector employees and for HR staff in 1995 and again in 2001.

The New Game of HR Management – In the Public Sector

These characteristics and traits of the ‘old game’ of HR management within the public sector will be pertinent for most libraries, as libraries are frequently considered to be a part of a municipal service or part of an educational institution, both of which fall within the public sector domain. Obviously, there would be some differences between the public sector and the private sector practices within HR management, and these would be primarily tied to compensation, rewards and recognition.

So, what was the prognosis back in 1995 for the way the game of HR management would be conducted by 2001?

Upon review of these different scenarios, which were initially written some fourteen years ago, it was quite shocking to see how much of the forecast for 2001 did indeed come to pass and continues to unfold. The other interesting element of reflecting on these scenarios is to see how slow many of the people in HR have been to develop and establish new methods and techniques to deal with the changing workplace of the twenty-first century. We have found that in many organisations, the groups that are most reticent about making changes in the way HR services are provided are sometimes the HR professionals. Their reluctance to move forward with the changing needs of employees becomes problematic because they are the very individuals who the members of the senior executive team turn to for advice when they are looking for ways to improve and enhance productivity and success through improved people management skills and practices. This may seem to be a harsh indictment of HR professionals as a whole, but as a member of this profession, one of the authors can attest to the numerous examples of reluctance to change their internal systems that have been in place for many years. At the same time, it is only fair to note that there are some very progressive HR professionals in the field who are leading the charge for new and improved ways to deliver their specific services to their clients. Major change begins with the will and desire of each individual to change. Without that sparkplug for change, the status quo always prevails. We will delve into the whole area of change management in much more detail in Chapter 5.

The changing paradigm of HR management

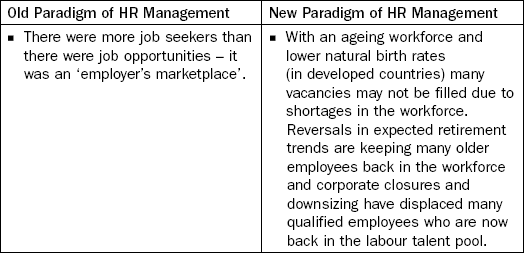

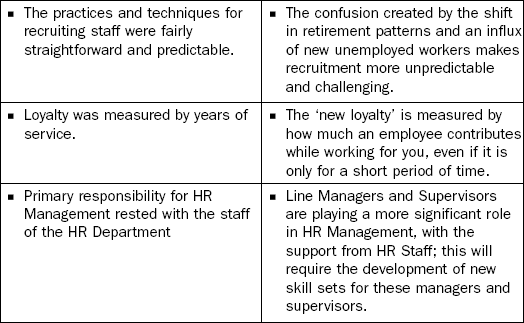

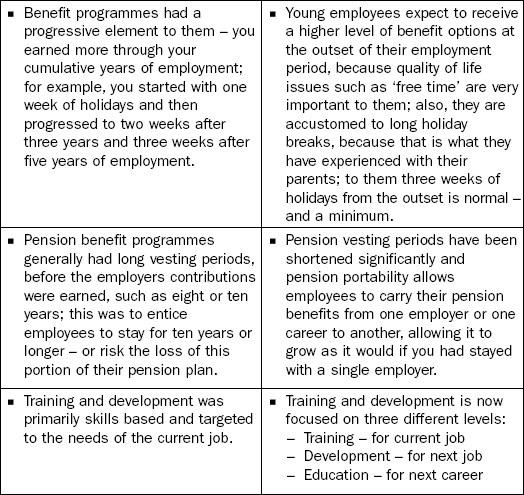

What is very clear, as we look at what is occurring now in 2009, compared with what was occurring at the turn of the century, is that the rules of the game have indeed changed:

![]() workplace working conditions have changed;

workplace working conditions have changed;

![]() employee expectations have changed;

employee expectations have changed;

![]() elements of the standard benefits package have changed;

elements of the standard benefits package have changed;

![]() the style of labour negotiations with unions and with professional associations has changed;

the style of labour negotiations with unions and with professional associations has changed;

![]() work and life balance components have changed;

work and life balance components have changed;

![]() techniques that once were satisfactory to staff have changed; and

techniques that once were satisfactory to staff have changed; and

![]() business conditions have changed dramatically.

business conditions have changed dramatically.

![]() With all of this change occurring, it would be helpful to look at what the major changes are between the ‘Old Paradigm’ of HR management from the year 2000 and the ‘New Paradigm’ of HR management of the years 2010–2015.

With all of this change occurring, it would be helpful to look at what the major changes are between the ‘Old Paradigm’ of HR management from the year 2000 and the ‘New Paradigm’ of HR management of the years 2010–2015.

This list of the changing paradigms in HR Management is not a complete list of all the changes that are eminent, but it is provided merely as an example of the level of change that is occurring within the field. If employers want to be attractive to the new group of employees entering the labour marketplace for their first full-time job, many of the items listed under the ‘new paradigm’ column will be needed. This means that organisations must begin moving in that direction – right from the senior executive level, to the HR Department and through to every manager and supervisor.

It is clear that employee expectations have changed dramatically. A job has to provide more than just gainful employment. Personal satisfaction, an improved work-life balance and the opportunity to make a meaningful contribution – both at work and in society – will be the hallmarks of the new workplace of 2015.

Common characteristics of people management

While the field of HR Management is expected to undergo many major changes, there are some things that are very common for employees of all types, from all different generational groups. With a solid understanding of the importance of these common characteristics, managers and supervisors will be well prepared to meet the needs and expectations of their employees, year after year.

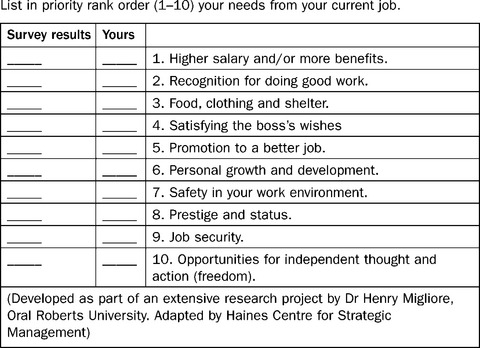

We have been using a simple assessment tool with our clients for more than fifteen years that asks employees to rank the importance of ten different elements about their current job. We call this tool the ‘Employee Needs Questionnaire’.

When we conduct this assessment, individuals fill out the questionnaire for themselves, with a ranking of 1 being the most important element and a ranking of 10 being the least important element. Once everyone has completed their own individual ranking, using the second column on the sheet, we run through each of the ten items, asking participants to raise their hands for each item if it was one of their top three rankings. We then record the number of responses for each item and post these on a flip chart sheet or a whiteboard.

After using this assessment with hundreds of client groups representing more than 10,000 employees taking part in workshops and seminars over the past 15–20 years, we have found a common pattern of responses:

![]() In approximately 93–95% of all cases, respondents selected the same items in their top three rankings:

In approximately 93–95% of all cases, respondents selected the same items in their top three rankings:

![]() The order of these three varied, but the same three items kept showing up within the top three choices.

The order of these three varied, but the same three items kept showing up within the top three choices.

![]() Again, in approximately 93–95% of all cases, the fourth item selected was:

Again, in approximately 93–95% of all cases, the fourth item selected was:

![]() The balance of the other six items showed no specific pattern of selection.

The balance of the other six items showed no specific pattern of selection.

So, what do these results mean for senior executives, managers and supervisors? How many times have we heard senior managers as well as HR professionals indicate that they feel that if we provide salary and benefit improvements, employee satisfaction will remain high? Unfortunately, that does not prove to be true in most cases. What is behind these results?

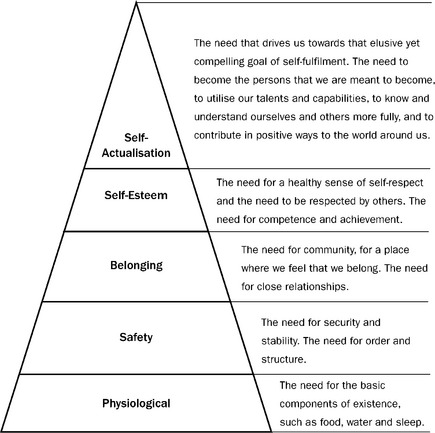

Abraham Maslow (1908–1970) first wrote about his ‘Hierarchy of Needs’ theory of human behaviour in a 1943 paper entitled ‘A Theory of Human Motivation’. A diagram of the five components that make up this theory is provided in Figure 3.2. This theory, which is a basic of every introductory psychology course, is one that most people are familiar with – but we sometimes forget the power of its implications on how staff function within our organisations.

In this theory, individuals are motivated to achieve satisfaction at the lower levels of the pyramid before demonstrating concern for achieving satisfaction at the higher levels of the pyramid. If one’s physiological needs for things such as food, water and sleep are met, then one worries about their needs for safety – security, stability, order and structure. When one’s safety needs are met, concerns about belonging surface as we seek a sense of community and establishing meaningful relationships with others. As one’s needs for belonging are satisfied, the issue of self-esteem becomes important in which self-respect and the respect of others becomes a priority. For some individuals, once they have achieved the levels of respect they need, they focus on achieving self-actualisation or the search for self-fulfillment. This fifth level of the Needs Hierarchy is one that many people seek yet few actually achieve, in part because of the fact that as one achieves a degree of self-actualisation, the desire for more continues to be exhibited. It may indeed be almost impossible to truly achieve a level of satisfaction at this fifth level.

This set of five levels of need has an intriguing aspect built into it. Regardless of the level that one is at, if something happens in their life that poses a threat to one of the lower levels, one’s attention immediately shifts to the lowest level need. One’s attention remains at this level until some degree of satisfaction has been achieved and then it is possible to again refocus on re-establishing satisfaction at the next higher level.

This self-focusing mechanism is an automatic reaction. From an employment perspective, if an employee is in a rewarding job that meets his or her financial and physiological needs while also providing a level of self-respect, their life will feel good. If they are suddenly laid off, because of a degree of business contraction, or through a merger of organisations that makes their current position redundant, the employee’s focus will immediately drop to the safety level – and it will stay there until that level is again satisfied. Even after an employee has found a new job opportunity and begins to re-build his or her career and life, they may be nervous and concerned about the last incident and be somewhat fearful of a recurrence. At the same time, their sense of accomplishment and capability will need to be re-built in their new position, while they are also working to build a new set of collegial relationships. This is why some employees may seem to be slow at adjusting after this type of traumatic change is thrust upon them.

The same responses can occur if an employee becomes seriously injured or ill, or if someone in their immediate family is threatened or harmed in some way or they face a severe financial setback that threatens their security and that of their family.

On the positive side, employees who are acknowledged for doing a good job can move up to the self-esteem level which predisposes them to more high-level performance. Opportunities for special project assignments or promotions will provide challenging situations in which many employees will rise to the occasion and produce outstanding results.

Let us go back to the results we have seen from the Employee Needs Survey presented earlier in this chapter. The ten elements included in this assessment are based upon Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. So, when we see results that indicate that personal growth and development, recognition for doing good work and opportunities for independent thought and actions are all in the top three responses, it is a clear indication that employees are in the fourth or fifth level of the hierarchy, as these three are all related to the Self-Esteem Level and the Self-Actualisation Level of the Needs Hierarchy. That means that all of their needs for physiology, safety and belonging are well satisfied. This is a signal that life in this organisation is stable and people feel a level of security and confidence.

On the other hand, if we were to conduct this assessment in an organisation that was in the throes of major staff layoffs, or had just recently been acquired by another firm, or had just experienced major changes in senior management positions, you can be assured that the results would be quite different as far as the priorities listed. In these cases, choices that relate to the belonging, safety and physiological levels of concern would predominate. But when all things are working relatively smoothly within your library, investing in the top three choices will yield a very good response from staff members – provided these opportunities are offered in a sincere and legitimate way.

What we have found interesting is that although Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs has been around as a working theory for more than seventy years, it still seems to be relevant. What does seem to be different is the way the Needs Hierarchy plays out in 2010 with different generational groups compared with 1980. It is also important to remember that in developing countries, this theory will be exhibited in different ways than in developed countries, but only with regard to scale. The same five levels will be present, but in developing countries, concerns for physiological needs and safety needs will be predominant, only because they have not yet achieved the level of satisfaction that would enable individuals to focus on the next higher levels. Until one’s daily needs and their sense of safety for themselves and their family can be satisfied and taken as a given condition of work life and community life, employees are less likely to be interested in things that appeal to their needs for belonging or self-esteem, let alone be motivated by these things.

In developed countries, these levels of need are just as important as ever – and, in fact, they may even be more important for younger generations than for older ones. However, there is a twist here, because older workers had to work, fight and sweat to achieve their physiological and safety needs. Once these were met, they had to be proactive and they pushed and prodded to ensure that management provided suitable opportunities to begin to meet their belonging and self-esteem needs. For younger generations of workers, much of the basic needs have been in place for many years, long before they entered the workforce. If they had a stable, economically secure family and home life, then these elements are almost taken for granted. Consequently, when these individuals enter the labour force, they tend to concentrate most on the third and fourth levels of need – to satisfy their needs for belonging and self-esteem. They may also be much more likely to engage in activities that lead to a sense of self-actualisation.

To demonstrate this belief, one of the authors has a daughter who is in her early thirties. She has a postgraduate degree in International Project Management and has spent the past two years working for an international aid agency on rebuilding projects in northern Pakistan and in southern China, following the devastating earthquakes that rocked these areas in 2005 and in 2008, respectively. Her interest is focused on making a meaningful contribution in a country where aid and support are needed desperately, to enable them to rebuild schools, homes and roads as they work to rebuild their economy through the re-establishment of farming activities in rural areas. Her needs are met because they are minimal to begin with. She has enough food, clothing and shelter not to have to worry about her physiological wellbeing. Her safety needs appear to be satisfactory to her, even though she is living and working in a foreign country where public security and safety cannot be taken for granted. She came home from this assignment wiser and more satisfied that she had done something to help make a difference in the world.

As a representative of an older generation, when I was her same age, I was more concerned for the health and safety of our family and for establishing a solid career base that would help to meet our needs for the future. My sense of contribution to society was limited to some local volunteer work with one or two community agencies, because that was all the time and energy I could provide. With the burden of a mortgage, loan payments and a growing family, my focus was on the economics of our family. My daughter does not have the same level of concern about her financial future, at the moment. She may later on, but today, with enough to get by, she is quite content to turn her attention to the needs of others, before being obsessively concerned about her own needs.

In her case, her employer does not try to motivate its employees through large salaries and bonuses. Instead, they advertise that their staff will have a chance to travel to different locations around the world, meet new people, live in different cultures, learn new languages and help to build a better world. They are provided with accommodation, food and other life conveniences. They also receive paid recreational time off every few months that enable staff to relax, regenerate, explore neighbouring areas of the world and come back refreshed and ready to carry on.

Through this example, we are trying to illustrate that these same needs exist, but they are at different levels for different people, depending on their own personal life situations. For employers, the key lesson here is to develop a sound understanding of the make-up of your workforce and be clear about what motivates them, then concentrate on providing the types of opportunities that meet their needs. In the case of a broad generational group of employees, a wider range of benefits and opportunities must be available to meet a wider range of needs and expectations.

Let’s briefly examine the four top priorities from the Employee Needs Questionnaire and see what impact they might have for younger workers, who are in the first five years of building their career path after completing an initial college or university education programme. This group has been labelled as ‘The Millennial Generation’ or the ‘Net Generation’ and their age group includes those born between 1978 and 1999, so, as we are writing this book in 2009, they represent employees 22–31 years of age.

1 Personal growth and development

Opportunities for growth and development are very important to today’s younger workers. They expect to receive opportunities for learning programmes, courses, conferences and other learning events. They do recognise that these are important elements for their career progression – and they generally have very high expectations about their own career potential and their own career progression. At times, some of these expectations are unrealistic. As one new young employee said to me, ‘If you guys don’t recognise that I am VP material and will probably reach this level within three years, then you must have rocks in your head.’ This notion of an inflated sense of capability was profiled in a series of articles printed in Canada’s National Post Newspaper’s ‘Meaning of Life Series’. This particular article, entitled ‘Workplace Cockiness the Way of the Future’ was the third installment in a four-part series called ‘No Fear Factor’. Drawing from a study by Linda Duxbury, one of Canada’s leading workplace researchers, and her colleague, Sean Foley of Carleton University’s Business School in Ottawa, this article states:

‘This younger generation has this unbelievable optimism about their abilities and their own future. They’ve been told all their lives that they can do anything. They have come to adulthood at a time when their technological savviness is valued and has allowed them to beat their parents from the time they were young. When you are eight years old and you program the VCR for your parents, that gives you a certain view of yourself and your abilities with regards to your superiors.

Their sense of entitlement is tangible. It’s in their demeanor. Even if they don’t talk about it, it is the way they carry themselves in the world.’3

To this younger generation, job experience gained over time carries less weight and value than skill, competency and education. While these three items are very valuable in the eyes of managers too, a dilemma arises because the two generations are often talking about significantly different skill sets. One thinks that computer capabilities, electronic game skills and multi-tasking are critical skills for survival in the world of work. Meanwhile, the older generation has come to the realisation that customer service skills, relationship skills, and the capacity to think and plan strategically are vital to business success. It’s almost as though the two groups were speaking different languages – and wondering why they are having difficulty understanding each other and communicating clearly to one another.

In order to be able to expand the skills that are needed, young employees will need to have opportunities to concentrate on skills that are not as developed as they need to be. Managers and HR professionals will need to develop ways of explaining this clearly to staff, so that they recognise the value and the need for this type of training and development. When the need for these skills is coupled with a clear understanding of the employee’s potential career path, this will be a lot easier for employees to understand. At the same time, managers also need to be open to learning more about ways in which a new employee’s technological capabilities can be used to improve processes and systems within the workplace.

There is some sound research that helps to explain why younger employees may not have some of the key skills, even though they make think they do. Researchers are finding that younger workers who are very adept at using technology, being able to multi-task and being able to grasp complex situations quickly are not as proficient at long-term planning and detailed decision-making. In an article in HR Magazine entitled ‘The Tethered Generation’, Kathryn Tyler outlines how today’s millennial generation has been so connected to state-of-the-art technology from birth that if they are not always ‘wired in’ to others they feel lost and disconnected. At the same time, these same individuals are in constant contact with their parents and their friends, seeking opinions and answers to their numerous questions. So, they are tethered in two ways – to their communication devices and to their social network of family and friends. As the article states, this can have a down side:

‘Scientists once believed the brain was almost completely formed by age 13. But, in the past two years, neuroscientists have discovered that parts of the brain – specifically the prefrontal lobes, which are involved in planning and decision-making – continue to develop well into the late teens and the early 20’s.

“The prefrontal cortex is important for decision-making, planning reasoning and the storage of knowledge”, explains Jordan Grafman, chief of the Cognitive Neuroscience Section at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke in Bethesda, Maryland.

That means millennials’ brains are still developing reasoning, planning and decision-making capabilities while they are heavily dependent on technology – cell phones, IM [instant messaging] and e-mail – as well as parents and friends at the other end of the technology. As a result, some experts believe millennials struggle to make decisions independently.’4

In this same article, Stephen P. Seaward, director of career development for Saint Joseph College in West Hartford, Connecticut, states:

‘The majority of millennials never experienced life without a microwave, computer, ATM card or television remote control … This instantaneous gratification … may have fostered unrealistic expectations with respect to goal-setting and planning. That, in conjunction with extreme parental influence, can prohibit creative problem-solving and decision-making.’5

A new employee’s skill development opportunities may be quite different from those of an older workforce too. For supervisors, this might seem unrealistic, because they will be using their own experience as the barometer and that will not be appropriate. If a new employee expects to have frequent opportunities for skill development and they are only provided with one or two chances a year, they will probably seek employment elsewhere, where their skills are being steadily developed. This suggests that the amount of budget dedicated to training and development opportunities, professional conferences and other learning opportunities will need to be increased. Most leading edge employers are prepared to invest an amount equal to 4–5% of their payroll costs for their training and development budget. Organisations that may have traditionally limited their training budget to only $500–600 per employee per year for this type of expense will probably find this more expansive approach excessive and will resist this change in business practice and in budget practice. If they do, they do so at their own peril.

2 Recognition for doing good work

For younger members of the workforce, acknowledgement and recognition are very significant. This is due in part to the fact that since they were very young, their parents and their teachers constantly reinforced their activities and reminded them about how important they were. Awards, professional recognition and acknowledgements of achievements, as well as ongoing day-to-day recognition for quality work and contributions are important for them to hear.

This does not mean that undeserved recognition is warranted. If employees are not completing their required assignments or if the quality of the work is substandard, this needs to be pointed out, along with advice as to how to improve performance. A clear description of the desired outcomes that are expected is very important. Ensure that this is provided up front and then review progress periodically to ensure that things remain on track. It is easier to adjust as things start to drift off line than it is to have the work redone after it has been completed improperly. This will require some monitoring of activity or some appropriate check and balance points built in, so that corrections, if needed, can be initiated early.

It may be hard for older workers who are providing supervisory or managerial responsibilities to deliver this level of attention. They often feel that their staff ‘ought to know what is expected and then just do it’. That is what was expected of them as they were building their careers, so why should it be different for the newer generation of employees? Older workers may not feel very comfortable handing out recognition or praise, because for many of them, it was not provided to them. So, it does not seem to be a very important issue for them – but it is for their staff. This creates a real ‘expectation gap’ between the generations. Making recognition and acknowledgement a common practice within your organisation could require some concentrated efforts, but the results are generally worth the effort.

One way to meet this need for feedback on how employees are doing is through the practice of periodic performance review sessions and regular feedback sessions. The standard organisational practice of conducting an annual performance review will probably be too infrequent for employees who are accustomed to receiving instant feedback in other parts of their lives, according to College Career Director Stephen Seaward, from St Joseph’s College, in West Hartford, Connecticut:

‘This [millennial] generation has grown up sitting in front of a monitor playing video games. Players always know how they are doing by the score on the screen. Therefore, this generation won’t want to wait for a semi-annual or annual performance review. They will require ongoing feedback.’6

Susan Revillar Bramlett is an HR generalist for a defence research contractor in Fort Wayne, Indiana, and she herself is one of the millennial generation. She confirms this need for periodic, ongoing feedback:

‘If I do something wrong, I expect my manager to let me know immediately, not at my next performance evaluation. If I’ve given a major presentation to company executives, I immediately follow up with someone who sat in on the call to gain feedback on how I did and how I can improve.’7

Not only is individual recognition important. Acknowledging the achievements of teams is also important. Younger workers are very comfortable in working within a team setting and in fact they thrive on it. They have been establishing solid social networks around themselves for many years through electronic networks such as MySpace, Facebook and Linked In. They expect that the work of the team will be noted. In many cases, the individuals are counting on the collaborative work of the team to achieve success. Futurist and author Jim Taylor, Vice Chairman of The Harrison Group in Waterbury, Connecticut, has this to say about the millennials:

‘… decisions are made in a team environment. They measure themselves by their peers. They will form communal tribes and communicate astonishing amounts.’8

In some ways this is very good news. Executives and managers have preached about the value of working together as a team for decades – and now we may actually have an opportunity to bring it to reality. The challenge will be to determine if we are able to pull it off. It may seem easy to talk about it; now we will have to deliver it and it may not be as easy as it seems. We may discover that ‘the teacher has much to learn from the student’. The older generation will also have to make many changes to bring about the team culture that has been so elusive for many of us in the past.

There is one more important point to note about recognition and acknowledgement. When some recognition or a reward for special effort is warranted, make sure that the form of recognition that is chosen is appropriate to the needs or interest of the individual employee. A colleague recently reminded us of the importance of this point. She had been working as an HR practitioner for a large oil company. Having successfully completed a very difficult project that required an extensive number of late evenings and weekends, her manager ‘rewarded’ her with two tickets for the next game of their local professional ice-hockey team. Little did her manager know that this almost amounted to an insult, as she hated the game of hockey. She was a strong supporter of the local performing arts community and attended many plays and dance recitals. Two tickets to one of these events would have been very meaningful and well appreciated. As it turned out, she was disappointed, the manger was oblivious as to what he had done unintentionally and the tickets ended up being wasted because they were discarded. Take the time to get to know your staff and what their interests and passions are. You will then be better prepared to provide rewards and recognition that not only achieve the desired results, but also make the employee feel truly valued, because you took the time to find out what would be meaningful to them.

As is so often the case, some of the most important things in life are the simplest. This applies to recognition and acknowledgement too. Employees have reported in a variety of studies that a simple ‘Thank You’ is still one of the most important forms of recognition, because it is a valid way to show that someone noticed and appreciated what they just did. It is a very easy technique to use and it costs nothing to deliver. Yet it yields a powerful payback and contributes a great deal to employee loyalty. Whenever we make reference to this point with our clients in working sessions, there is common agreement – and then they note that it is seldom practised. Why is it so hard for managers, supervisors and colleagues to display this simplest and most important acknowledgement? If this technique is hard to adopt, how can we expect other forms of recognition to become common practice? As recognition and acknowledgement are so important in helping to create a motivating workplace environment, it may be time to make ‘Thank You’ a frequent part of our daily vocabulary.

One company in the USA that specialises in providing packages for employee recognition is Maritz, whose headquarters are in Fenton, Missouri. They have offices worldwide and as it states on their website, ‘We have been practicing the science and art of people and potential for over 100 years.’ So, it’s obvious that they have picked up a few key points along the way. Melissa Van Dyke is a Practice Consultant in their Employee Engagement Practice and she has posted a short article on their website entitled ‘The Top Ten Tenets of Enterprise Recognition’ (www.maritz.com).

Here is a brief summary of the Top Ten Tenets of Enterprise recognition, as outlined by Van Dyke:

‘Maritz believes strongly that the most effective tool to create and sustain a culture that engages and aligns employees behind business imperatives is a performance-based recognition approach we call Enterprise Recognition Management… Below are the top ten tenets that define our unique approach.

![]() Empower Managers: … Based on the work of Dr. Bob Nelson, we know that many managers will never use recognition as a motivational tool because they do not know how, they do not feel it is their job, or they do not feel their employees value it… All managers should be empowered with recognition training. Training that helps them identify employees’ unique motivation profiles, assess their own strengths and weaknesses in positive reinforcement, and most importantly, identify how real-time recognition can help them motivate their employees to meet their own personal business goals.

Empower Managers: … Based on the work of Dr. Bob Nelson, we know that many managers will never use recognition as a motivational tool because they do not know how, they do not feel it is their job, or they do not feel their employees value it… All managers should be empowered with recognition training. Training that helps them identify employees’ unique motivation profiles, assess their own strengths and weaknesses in positive reinforcement, and most importantly, identify how real-time recognition can help them motivate their employees to meet their own personal business goals.

![]() Ensure Meaningful Recognition: From years of employee research polls, Maritz knows statistically that a significant portion of the U.S. workforce is not consistently recognized in ways that are meaningful … It is therefore imperative that an organization understands what types of rewards and recognition are most meaningful to its particular employees at an enterprise level and, most importantly, at an individual level .

Ensure Meaningful Recognition: From years of employee research polls, Maritz knows statistically that a significant portion of the U.S. workforce is not consistently recognized in ways that are meaningful … It is therefore imperative that an organization understands what types of rewards and recognition are most meaningful to its particular employees at an enterprise level and, most importantly, at an individual level .

![]() Measure Success: … Modern recognition tools allow organizations to capture, track and report the exhibited behaviours on which recognition was based … Every recognition program should be based on measurable business objectives with accompanying metrics.

Measure Success: … Modern recognition tools allow organizations to capture, track and report the exhibited behaviours on which recognition was based … Every recognition program should be based on measurable business objectives with accompanying metrics.

![]() Commit From the Top: The primary reason for the failure of many recognition programs is either an out-dated executive view that recognition and rewards are soft topics devoid of bottomline impact or a failure of the general employee population to believe that executive management supports recognition …

Commit From the Top: The primary reason for the failure of many recognition programs is either an out-dated executive view that recognition and rewards are soft topics devoid of bottomline impact or a failure of the general employee population to believe that executive management supports recognition …

![]() Consolidate Efforts: Tighter alignment, increased visibility, administrative efficiency, and economies of scale are just a few of the organizational benefits for developing and maintaining a strategic, enterprise-wide reward and recognition effort …

Consolidate Efforts: Tighter alignment, increased visibility, administrative efficiency, and economies of scale are just a few of the organizational benefits for developing and maintaining a strategic, enterprise-wide reward and recognition effort …

![]() Decentralize Ownership: A consolidated, enterprise-level recognition strategy should not preclude individual work groups from owning and implementing the recognition strategy in a manner that will be particularly meaningful to the employees in their division …

Decentralize Ownership: A consolidated, enterprise-level recognition strategy should not preclude individual work groups from owning and implementing the recognition strategy in a manner that will be particularly meaningful to the employees in their division …

![]() Align With Corporate Goals, Values: … alignment … does not happen at the enterprise level: it happens in individual day-today actions of every employee … All recognition programs should be designed to clearly communicate and encourage the values and behaviors the organization is promoting while not stifling the creativity that employees will show when exhibiting these behaviours.

Align With Corporate Goals, Values: … alignment … does not happen at the enterprise level: it happens in individual day-today actions of every employee … All recognition programs should be designed to clearly communicate and encourage the values and behaviors the organization is promoting while not stifling the creativity that employees will show when exhibiting these behaviours.

![]() Apply Consistently and Equitably: Employee recognition programs that are implemented with no guidelines and complete discretion over who and what gets awarded ultimately get viewed as “favourite pet” awards …

Apply Consistently and Equitably: Employee recognition programs that are implemented with no guidelines and complete discretion over who and what gets awarded ultimately get viewed as “favourite pet” awards …

![]() Recognize Real Time Performance: … Organizations should foster a culture where employees are awarded in real-time for exhibiting the defined behaviours that drive overall company performance.

Recognize Real Time Performance: … Organizations should foster a culture where employees are awarded in real-time for exhibiting the defined behaviours that drive overall company performance.

![]() Continuously Improve: Lack of freshness is the single largest complaint among employee participants in on-going recognition initiatives …. Dedicated recognition advocates should meet frequently to share ideas, capture best practices and make changes to the programs …’9

Continuously Improve: Lack of freshness is the single largest complaint among employee participants in on-going recognition initiatives …. Dedicated recognition advocates should meet frequently to share ideas, capture best practices and make changes to the programs …’9

Although some of the language in this article seems to apply primarily to companies, the principles are identical for any public sector organisation – including libraries. How much attention do you pay within your library to this important topic of staff recognition? Or, like so many public sector organisations, do you leave it to chance, because of the belief that employees should be grateful that they have a job and besides public funds should not be used to reward employees. Why is it that we want the results that private sector organisations are able to achieve, but we are not prepared to use the same lessons and tools that they have found to be so important in achieving those results? Having worked in the public sector for more than twenty years I have never been able to reconcile the inconsistencies of this stance. We need to study what works and then have the courage to implement it in a fair and equitable way. Library patrons no doubt will be pleased if your employees end up providing superior service because they are proud to work in your library, where their extra efforts are acknowledged and rewarded in some small way.

3 Opportunity for independent thought and action

To many employees, this element is all about the concept of empowerment. Do you provide opportunities for employees to become actively engaged in decision-making in a meaningful way, so that they feel they are making a real contribution?

This is an intriguing issue because many older workers feel that employees should ‘earn the right’ to be actively involved in decision- making through their cumulative job experiences. This is how things were as they were working their way up the corporate decision-making ladder. However, things are no longer the way they were. Younger generations have a very different attitude about their own value.

Younger generations have grown up in a world where their opinions were sought out by so many different people – parents, teachers, pollsters, politicians and business leaders – through surveys, feedback cards, focus groups and special study sessions. With the rise in popularity of reality television programmes where viewers select the winners of various competitions, such as American Idol, and through media channels such as U-Tube, they can see first hand the degree of influence they have as they watch society respond to their statements and viewpoints. As one example, during the 2007 round of candidate events for the nomination of the presidential candidates for the two political parties in the USA, leading up to the 2008 presidential election, an open debate was staged using Facebook. Candidates were presented with live questions from citizens over the Internet on any topic. As the 2008 US Presidential election campaign unfolded, the significance of the way that young voters became engaged through social networking sites to elect Barack Obama marked a new chapter in the world of opinion gathering and local activism in the political arena.

Consequently, this new generation of employees expects to be able to offer their opinions and views on important workplace issues. It will be necessary for managers to become skilled at seeking out, sorting out and considering the opinions of their staff members to a much higher degree and on a more regular basis than ever before.

Workplace democracy is on the rise and it is producing a new sense of employee empowerment. For this culture of empowerment to be effective, employees need to be prepared to be actively involved in the decision-making process – and also to be prepared to accept responsibility and accountability for those decisions and the results that are produced. On the other side, managers need to learn how to be able to share the decision-making responsibility by ensuring that staff are cognizant of the implications of their decisions and are prepared to accept accountability for the results. This issue will be discussed in more detail when we examine the ‘Top ten critical HR management issues within a library’ in Chapter 8.

4 Higher salary and more benefits

As already noted, this element usually appears as the fourth most important issue on the Employee Needs Questionnaire. There are a variety of views about the importance of compensation for younger workers. On the one hand, in developed countries, many of them have been raised in a fairly well-to-do society where their financial needs were provided for regularly. Financial experts have noted that the younger generations of society are in a position to inherit significant amounts of money from their parents over the next twenty years. In some cases, parents have been distributing this money in advance by helping their children with funds for home purchases, repayment of education loans, etc. Consequently, many young people today are living in a relatively good state of financial health. This, of course, cannot be taken as a broad generalisation that applies to all young people – it varies on a case-by- case basis – but it is safe to state that most young people today are in a better state of financial health as they start their careers than their parents were when they were at the start of their careers.

A second point of view is that many younger people today are not as driven by the need for wealth and have learned to survive on less than their parents expected. If money is not their primary motivator, then it is important to find out what does motivate them. For many members of Generation Y and the Millennial Generation, they are primarily interested in a job that contributes something valuable to society. This altruistic attitude provides them with the level of satisfaction that they seek.

Although money can no longer be considered the primary motivator for employees, one lesson is clear. When money is distributed in a way that is viewed to be unfair, inappropriate or unjust, it will become a huge de-motivator. Therefore, it is important to see that compensation levels and financial rewards are distributed in an equitable way that reflects the level of contribution made by each individual. That is equitable – not equal. There is a big difference between these two concepts.

With regards to benefits, the current ranges that are available in most developed countries is quite adequate to meet the needs of many employees. Health insurance, dental and eyecare coverage, disability insurance, improved workplace conditions and working conditions, sick pay, pension plans, etc., have been established for many years through the foresight, dedication and hard work of many leaders on both sides of the contract bargaining tables over the past thirty or forty years. In fact for many employees, these benefits have been around as long as they have been in the workforce and they are sometimes taken for granted as an automatic right. Newer employees have little awareness of the struggles that previous generations of labour leaders had to endure to enshrine such benefits for the vast majority of employees today. Nor do they care much about these struggles, because as far as they are concerned, these benefits are accepted as a given – they have become their automatic rights, their entitlements.

This level of complacency has been abetted somewhat by the establishment of labour legislation that makes many of these types of benefit programmes mandatory for employers to provide. It is very easy to overlook the fact that for many employers, these benefits come with a hefty price tag – they amount to approximately 30–35% of all payroll costs in many organisations. For most employees, they never think about this cost because it is now viewed as an ‘employee right’.

The one benefit that does seem to be very significant for younger workers is flexible time and time off. Younger workers really value their own free time. They do not like to work overtime and they definitely want to be able to adjust their workday schedule to enable them to engage in other activities that they consider to be important. This could include time to attend school functions with their children, time to attend to the needs of ailing parents, time for personal activities, and time to attend fitness classes before work, during the lunch hour or in the late afternoon, as part of their daily routine. Although none of these activities is questionable from the perspective of their value to the employee and his or her family, they can create havoc with work scheduling. Longer holidays, banked time for overtime worked or time credited for sick leave that was not needed all create a significant liability to the organisation, primarily because much of it is an ‘invisible liability’ that is often not calculated as a cost and ends up as an unfunded liability.

In order to accommodate the preferences of employees and also reduce or eliminate the extended unfunded liability that can occur, organisations are making it mandatory for employees to utilise their extra time benefits within a fixed period of time or risk losing the privilege. Recently, within Canada and the USA, labour contracts are being drafted that place the onus on the employee rather than the employer to use up their time that is due, rather than seek large payouts when they are due to retire. With the retirement boom that is just around the corner, the financial implications of paying out large sums for unused holiday time, overtime or sick pay, many organisations are facing some hefty compensation costs, at the very time when they will need those same dollars to lure new recruits who can replace the retiring workers. It is shaping up as ‘the perfect storm’ for HR professionals and corporate executives alike.

Organisations are beginning to recognise the value of allowing employees time to claim these benefits when it can be accommodated within the work schedule. In fact some employers are advertising time flexibility as one of the key attractors for people if they are considering joining their organisation. We have one client who openly states that if employees need to have a time schedule that is different than the normal one, to accommodate other obligations, it can be arranged. This often ends up as a job-sharing situation where two employees share the responsibilities and the schedule of one job. With this type of arrangement all parties win – the two employees are pleased that their needs could be met, the employer has two very satisfied, loyal employees and there is no additional cost required to make this work. It does mean that the coordination of work needs to be handled wisely to ensure that things don’t fall between the cracks as one employee leaves for a few days and the other takes over. In our client’s case, the only down side they experienced when they first started with this type of arrangement was that some staff did not understand that the employees whose requests for less time ended up receiving only a proportional salary for their work, pro rata. Some staff felt that others were being paid the same salary, but were required to work less time. Once this was understood and all staff became aware of the terms for this accommodation of schedules, things have been running very smoothly. Tell people what is happening. Don’t let assumptions and unfounded rumours unravel a good arrangement.

With the potential for more employers seeking employees who are willing to work split shifts or only work part-time, it is important to recognise that these employees should also be provided with benefits similar to full-time staff, only pro-rated to an amount equivalent to their schedules. Many employers are now providing partial healthcare coverage, partial holiday allowances, and partial pension plan contributions to their casual and part-time staff, provided they work a minimum number of hours per week, such as 16 or 20 hours. For this option to be implemented, many HR staff had to be convinced that the extra work of handing these customised benefit programmes would yield an overall benefit to the organisation through better recruitment and staffing of skilled employees who were very appreciative of this optional benefit programme and ended up being very loyal to the organisation as a result. Of those organisations that have introduced this type of adaptable benefits programme, we have not seen one that has regretted their decision or tried to revert back to the old way of administering benefits.

For libraries, this will require corporate support from the municipality or the university, as it will create havoc if only some employees of larger institutions are eligible for this type of consideration. However, library HR staff can and should become advocates for this type of arrangement, if it does not yet exist. With more and more utilisation of part-time employment on the horizon, those who adopt this approach early will be the ones that are best able to attract employees, in spite of a tight labour marketplace.

Now that we have a better understanding of what motivates employees in this era and how it differs from past eras, we need to investigate a method for developing a sound corporate Strategic HR Management Plan or a ‘Strategic People Plan’ that will identify the key strategies to be pursued if you wish to reap the best return on your people investment over the next 3–5 years. At the same time, we will also outline a new way of thinking about planning and change management practices, using the ‘Systems Thinking Framework’. We will also show you how this approach is beginning to provide solid evidence that it is a much more effective way to ‘plan your work and work your plan’ to achieve outstanding results.

Summary

![]() We outlined the concept of ‘The Game of Business’ and demonstrated how it could be applied to the business of HR Management

We outlined the concept of ‘The Game of Business’ and demonstrated how it could be applied to the business of HR Management

![]() We provided a comparison of the way that the game of HR Management has changed from 1995 to 2001 and also examined some of the realities of the new paradigm of HR Management as we move towards 2010

We provided a comparison of the way that the game of HR Management has changed from 1995 to 2001 and also examined some of the realities of the new paradigm of HR Management as we move towards 2010

![]() We explored some of the common characteristics of HR Management or People Management that seem to have withstood the test of time and still have relevance for employees today

We explored some of the common characteristics of HR Management or People Management that seem to have withstood the test of time and still have relevance for employees today

![]() We examined two tools – the Employee Needs Questionnaire and Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs – to explain why some of the common characteristics of People Management from years past are still valid

We examined two tools – the Employee Needs Questionnaire and Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs – to explain why some of the common characteristics of People Management from years past are still valid

![]() We delved into the top four common characteristics of employee satisfaction and examined some of the current situations that seem to impact each of these characteristics for older as well as younger employees

We delved into the top four common characteristics of employee satisfaction and examined some of the current situations that seem to impact each of these characteristics for older as well as younger employees

The ART of People Management

A – Attention

![]() It is important to pay attention to the differences between the needs and expectations of younger staff members regarding personal and career development opportunities, compensation, benefits and flexible time options. They are often quite different from what you might expect – or are currently providing.

It is important to pay attention to the differences between the needs and expectations of younger staff members regarding personal and career development opportunities, compensation, benefits and flexible time options. They are often quite different from what you might expect – or are currently providing.

R – Results

![]() Many HR staff and library managers will need to re-think their current paradigms related to the practices of People Management. They may also need to make any adjustments needed to ensure that they are providing the type of support services that your staff and work teams require to be fully engaged and committed as they work to carry out your corporate plan.

Many HR staff and library managers will need to re-think their current paradigms related to the practices of People Management. They may also need to make any adjustments needed to ensure that they are providing the type of support services that your staff and work teams require to be fully engaged and committed as they work to carry out your corporate plan.

T – Techniques

![]() Managers can use the Employee Needs Questionnaire and then conduct candid discussions with staff about the results in order to clarify what they are really looking for in their workplace.

Managers can use the Employee Needs Questionnaire and then conduct candid discussions with staff about the results in order to clarify what they are really looking for in their workplace.

![]() Look for ways to connect the different generational groups in your workplace to share their different opinions and perspectives about work, core values and what is needed for career advancement. Don’t let the differences become barriers.

Look for ways to connect the different generational groups in your workplace to share their different opinions and perspectives about work, core values and what is needed for career advancement. Don’t let the differences become barriers.

![]() Never underestimate the importance of recognition for employees of all ages. Instil the practice of acknowledging the good work of staff in a variety of ways. But don’t overlook the use of performance improvement discussions and practices when they are required to create the turnarounds in behaviour that are needed to produce the desired results.

Never underestimate the importance of recognition for employees of all ages. Instil the practice of acknowledging the good work of staff in a variety of ways. But don’t overlook the use of performance improvement discussions and practices when they are required to create the turnarounds in behaviour that are needed to produce the desired results.

1.Stack, Jack and Burlingham, Bo (1992) The Great Game of Business: Unlocking the Power and Profitability of Open-book Management. New York: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc., pp. 7–8.

3.Owens, Anne Marie (2007) ‘Workplace Cockiness the Way of the Future’, National Post, Toronto, Ontario. (Note: This was the third instalment in the ‘Meaning Of Life Series’ and it was entitled ‘No Fear Factor’. This specific column was the second of four parts in this series. My copy of this article did not contain a date or page reference. Efforts to secure the specific date of this reference information have not been successful.)

4.Tyler, Kathryn (2007) ‘The Tethered Generation’, HR Magazine, May, pp. 42–3.

5.Ibid, p. 43.

6.Ibid, p. 46.

7.Ibid, p. 46.

8.Ibid, p. 46.

9.Van Dyke, Melissa (2007) ‘The Top Ten Tenets of Enterprise Recognition’, www.maritz.com