Complete Evaluations and Understanding |

Evaluations of artistic elements from previous chapters will be drawn together and compared here. Observations will be made from examining evaluations and comparing the artistic elements to the musical materials.

The evaluations made have been on three different levels of perspective: (1) the characteristics of an individual sound, (2) the relationships of individual sound sources, and (3) the overall musical texture, or overall program.

This chapter will examine relationships of the various dimensions of the overall texture and explore pitch density. The information offered by comparing the various evaluations of individual sources is explored next. An examination of how the artistic elements shape a recording will lead to a summary of the system for evaluating recorded/reproduced sound.

The highest level of perspective brings the listener to focus on the composite sound of a recording. At this level, all sounds are summed into a single impression. Recreational listening usually is mostly focused on this level of perspective, with shifts of focus moving to text and melody—and other aspects attractive to the listener, such as beat or pulse—in a random manner and at undirected times.

This single impression of the overall texture has a variety of dimensions that provide the recording and music with its unique character. These dimensions are the piece of music/recording’s form, perceived performance environment, reference dynamic level and program dynamic contour, and its pitch density. All but one of these dimensions has been explored in previous chapters.

The process of evaluating pitch density is directly related to pitch area analysis from Chapter 6. Pitch density is the amount and placement of pitch-related information within the overall pitch area of the musical texture. It is comprised of the pitch areas of the musical materials fused with the sound qualities of the sound sources (voices, instruments, or groups of instruments and voices) that present the material.

The concept of pitch density allows each musical idea/sound source to be perceived as having its own pitch area in the musical texture. The range of pitch that spans our hearing (and the musical texture) can be conceived as a space. Within this space, sound sources appear to be layered according to the frequency/pitch area they occupy. The range of pitch is divided into areas occupied by the sound sources, or left empty. The size and placement of these areas are unique to each piece of music, and may remain stable or change at any time.

With this approach, the concept of pitch density is often applied to the processes of mixing musical ideas and sounds in recording production. This is similar to the traditional concept of orchestration, where instruments are selected and combined based on their sound qualities, and the pitch area the sounds occupy. The recording medium and various formats provide new twists to this traditional approach to combining sounds.

Pitch density will be evaluated to determine the pitch areas occupied by musical materials, fused with the sound quality of the sound source(s) presenting the material.

Musical materials are a single concept or pattern. These materials will fuse in our memory and perception as a group of pitches, which occupy a pitch area. The pitch area of the musical material is defined by its boundaries—its highest and lowest pitches. Within the boundaries, the number of different pitch levels that comprise the musical material and their spacing creates a density in the pitch area.

The pitch area of the sound source will also influence the pitch area of the musical idea. The primary pitch area of the sound source will often be the fundamental frequency of an instrument or voice, perhaps with the addition of a few prominent lower partials. A primary pitch area may also contain environmental cue information (delayed and reverberated sound). These cues may add density to the sound without adding more pitch information. Pitch-shifted information, and other processing effects, may also provide additional spectral information and added density.

Often, the primary pitch area of the sound source is rather narrow, often slightly more than the fundamental frequency alone. This is especially true when an instrument or voice is being performed at a moderate to low dynamic level. As the dynamic level of a sound source increases, lower partials will often become more prominent, and the width of the pitch area will tend to widen.

The pitch area of each musical idea must be determined by (1) defining the length of the idea. It is then possible to define (2) the lowest boundary of the pitch area, then (3) the highest boundary of the area. This pitch information is determined by the listener calculating the melodic and harmonic activity of the musical idea (to determine the highest and lowest pitch-levels), then adding detail pertaining to the sound qualities of the sources performing the idea. Most listeners can easily accomplish this sequence by simply asking “when does this idea end, and when does the next idea begin?”

The lowest boundaries of pitch-areas are most often the fundamental frequencies of the sound sources performing the musical material (roughly following the melodic contour or the lowest notes of a chord progression). The upper boundary is either the highest pitch-level of the musical material, or is the top of the predominant pitch-area of the highest sound source (and pitch-level) of the musical idea. The boundaries of pitch areas of musical ideas may or may not change over time.

The pitch area of a musical idea is a composite. It contains all of the appearances of the sound source performing all of the pitch-material within the time period of the musical idea. It is the sum of all of the pitch levels and the primary pitch areas of its sound source(s).

The individual sound source is conceived as a single pitch area and is identified by boundaries that conform to the composite pitch material. The relative density of the idea is determined by the amount of pitch information generated by the musical idea and the spectral information of the sound source(s).

The process of determining pitch area is repeated for each individual musical idea. All sounds will appear on the graph.

Pitch areas may be mapped against a time line. If a time line is used, changes in pitch area as the musical idea unfolds in time can be presented (as appropriate to the musical context).

All sound sources are plotted on the pitch density graph. The graph may take two forms, with or without a time line. The graph may simply plot each sound source’s pitch area against one another (as the pitch area graph, in Chapter 6). Most helpful is when the sound sources are plotted against the work’s time line, allowing the graph to visually represent changes in pitch density as the work unfolds.

In either form, the pitch density graph contains:

• |

Each sound source is represented by an individual box denoting the pitch area |

• |

The Y-axis is divided into the appropriate register designations |

• |

The density of the pitch areas should be denoted on the graph through shadings of the boxes or verbal descriptions |

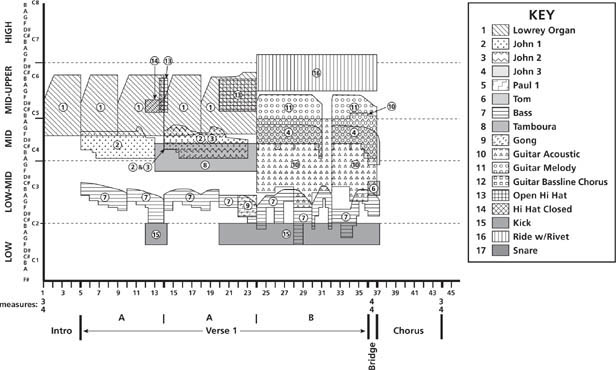

Figure 10-1 Pitch density graph—The Beatles’ “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.”

The pitch areas of all of the sound sources may be compared to one another and to the overall pitch-range of the musical texture. Pitch density allows the pitch area of all sound sources to be compared. Thus, the recordist is better able to understand and control the contribution of the individual sound source’s pitch material to the overall musical texture and of the mix.

The pitch density of the beginning sections of The Beatles’ “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” (1999 Yellow Submarine version) appears in Figure 10-1. The work uses pitch density and the register placement of sound sources and musical ideas to add definition to the musical materials and sections of the music. Pitch density itself helps create directed motion in the music. The musical ideas are precisely placed in the texture, allowing for clarity of the musical ideas. The expansion and contraction of bandwidth of the overall pitch range and textural density of the musical ideas (and sound sources) add an extra dimension to the work and support it for its musical ideas.

A pitch density exercise appears at the end of this chapter. The reader is encouraged to spend enough time with this exercise to feel comfortable with this concept, which is so important to the mixing process.

Examining Characteristics of the Overall Texture

The characteristics of the overall texture provide many fundamental qualities of the music and recording. These greatly shape the music and its sound qualities, and communicate most immediately to the listener. The framework for the music and the context of the message of the recording are crafted at this level of perspective.

The characteristics of the overall texture are:

• |

Perceived performance environment |

• |

Reference dynamic level |

• |

Program dynamic contour |

• |

Pitch density |

• |

Form |

The perceived performance environment creates a world within which the recording exists. This adds a dimension to the music recording that can substantially add to the interpretation of the music. The level of intimacy of the recording is related to the level of intimacy of the message of the music. This element will largely be defined by the sound stage as placed in the perceived performance environment.

The reference dynamic level represents the intensity and expressive character of the music and recording. What the music is trying to say is translated into emotion, expression, and a sense of purpose. These are reflected in recordings and performances as a reference dynamic level. Understanding this underlying characteristic of the music allows the recordist to calculate the relationships of materials to the inherent spirit of the music.

The program dynamic contour allows us to understand the overall dynamic motion of the entire piece of music. Actual dynamic level will impact the recording process in many ways, and it also shapes the listener’s experience. While program dynamic contour depicts how the work unfolds dynamically over time, this contour is often closely matched to the drama of the music. The tension and relaxation, the points of climax and repose, movement from one major idea to another, and more are contained in the contour of this sum of all dynamic information.

Pitch density provides information on the spectrum and spectral envelope of the entire musical texture. The movement of musical ideas through the “vertical space” of pitch provides a sense of place for musical materials and adds an important dimension to the character of the overall texture. The actual sound quality of the overall texture is largely shaped by pitch density. Pitch density can be envisioned as providing spectral information—materials that are harmonically related, and those that are not all add their unique qualities to the production as they change over time or provide a continual presence that is part of the overall sound of the recording/music.

Finally, the form of music is created by all of these characteristics, plus the text and musical materials. This essence of the song is what reaches deeply into the listener. It resonates within the listener when the song is understood. Form is the overall concept of the piece, as understood as a multidimensional, but single idea.

Figure 10-2 presents a time line and the structure of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.” This is an outline of the materials that contribute to the form of the piece. The shape of the music and interrelationships of parts, as well as elements of the text, can be incorporated into this graph and made available for evaluation.

Figure 10-2 Time line and structure—The Beatles’ “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.”

Matching the text against the structure of the piece will allow the reader to notice recurring sections of text/music combinations—verses and choruses. The musical materials enhance nuances of the meaning of the text as they were captured and enhanced by the recording process.

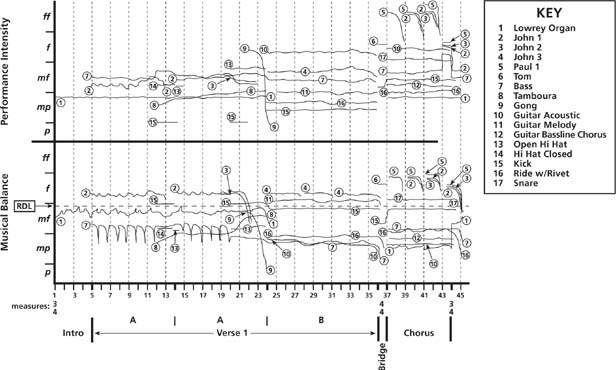

Dynamic relationships between the various sections of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” are present. These are clearly observed in the program dynamic contour graph (Figure 10-3). The graph also shows the overall shape and dynamic motion of the song. The reader can also explore how that motion relates to the song’s text and sense of drama.

The reference dynamic level of the song is also identified in Figure 10-3, as a high mezzo forte.

The pitch density graph of the song in Figure 10-1 allows the reader to identify and understand how the song emphasizes one pitch area for a time, then more evenly distributes pitch area information—moving from one texture to another between sections. An evaluation of the perceived performance environment will provide the last of the characteristics of the overall texture, allowing all to be compared and considered. Through this process important and fundamental characteristics of the song can then be more readily understood and communicated to others.

Relationships of the Individual Sound Sources and the Overall Texture

The mix of a piece of music/recording defines the relationships of individual sound sources to the overall texture. In the mixing process, the sound stage is crafted by giving all sound sources a distance location and an image size and stereo/surround location. Musical balance relationships are made during the mix, and relationships of musical balance with performance intensity are established. The sound quality of all of the sound sources is finalized at this stage also, as instruments receive any final signal processing to alter amplitude and frequency elements to their timbre and environmental characteristics are added.

These elements crafted in the mix exist at the perspective of the individual sound source. Many important relationships exist at this level. This focus is common and important for the recordist, but is not common in recreational listening. The many ways sound is shaped at this level brings the recordist to often focus on this level. Learning to evaluate these elements, and to hear and recognize how these elements interact to craft the mix is very important for the recordist.

Figures 7-4 and 10-4 present two musical balance graphs of the beginning sections of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.” These are evaluations of two separate versions of the song. Mixing decisions brought certain sounds to be at different dynamic levels in each version. Listening with a focus on several different sound sources, while comparing the two graphs to what is heard, will provide the listener with insight into these very different mixes. The performance intensity tier of Figure 10-4 should also be examined and then compared to the final dynamic levels. Here the reader is able to identify how the dynamics of the sounds were transformed by the mixing process. This gives much insight into the performance of the tracks and their sound qualities, and the musical balance decisions that followed.

Figure 10-3 Program dynamic contour—The Beatles’ “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” (1999 Yellow Submarine version).

Figure 10-4 Musical balance versus performance intensity graph—The Beatles’ “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” (1999 Yellow Submarine version).

The sound stage provides each recording with many of its unique qualities. In examining the structure of sound stage the listener will learn many things about a recording. Among the variables are:

• |

Distribution of sources in stereo or surround location |

• |

Size of images (lateral and depth) |

• |

Clearly defined sound source locations, or a highly blended texture of locations (wall of sound) |

• |

Depth of sound stage |

• |

Distribution of distance locations |

• |

Location of the nearest sound source |

• |

Sound stage dimensions that draw the listener’s attention or are absorbed into the concept of the piece |

• |

Changes in sound stage dimensions or source locations |

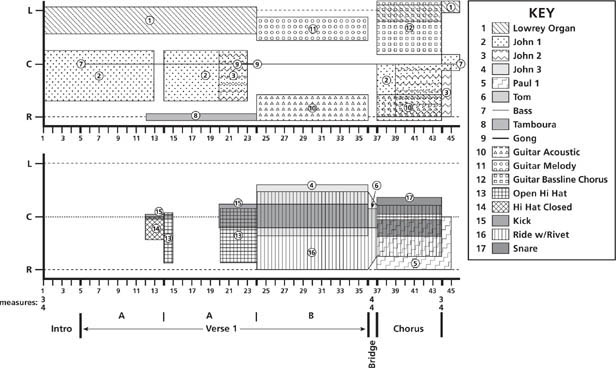

Figure 10-5 presents the stereo location of sound sources in the 1999 Yellow Submarine version of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.” The phantom image locations and sizes add definition to the sound sources and musical materials, and the width of several images changes between sections.

Comparing this stereo location graph to surround placements in Figures 10-6 and 10-7 allows some interesting observations. The lead vocal, Lowrey organ, and tamboura have been graphed from the first verse in the surround version, and both graphs need to be used to clearly define their dimensions. The image sizes and locations in a surround mix are quite different from the two-channel versions, and offer a very different experience of the song. Comparing these location graphs will allow the reader insight into what makes each mix different.

The reader is encouraged to also evaluate the stereo location of the sources in the original Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band version of the song. Then compare the three location evaluations for similarities and differences of image location and sizes, and note when and how images change sizes or locations. In the end, consider how the different sizes and locations of the images impact the musicality of the song.

Figure 10-5 Stereo location graph—The Beatles’ “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” (1999 Yellow Submarine version).

Figure 10-6 Surround sound location graph—The Beatles’ “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds,” Lowrey organ, tamboura, and vocal images.

Figure 10-8 is a blank distance location for the beginning sections of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.” The graph can be used to plot the distance location of sources from any of the three versions of the song—or comparing one or more selected sources from all three versions. In listening to the three versions of the song, the reader will notice some striking differences in distance location. Between the two-channel versions sound source changes in distance locations are more pronounced in the Yellow Submarine version, and during the first verse the bass and lead vocal are closer than in the Sgt. Pepper version. Consider how distance cues enhance certain musical ideas and sound sources, and provide clarity or blending of images in various instances.

The sound quality of all of the sound sources shapes the pitch density of the song. It also contributes fundamentally to the performance intensity of the sound source, and in some cases may contribute to determining the song’s reference dynamic level. The environmental characteristics of the source also contribute to its overall sound quality. They fuse with the source’s sound quality to add new dimensions and additional sound quality cues to the resulting composite sound. Lastly the sound quality of each source provides important distance information, as the amount of timbral detail primarily determines distance location.

Figure 10-7 Surround image placements of Lowrey organ, tamboura, and vocal images—The Beatles’ “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.” Dots depict density and area of vocal image.

This timbral detail carries over into clarity of sound source timbres in the mix. Sound sources can have well defined timbres with extreme detail and clarity. Conversely, their sound qualities can be well blended with details absorbed into an overall quality. Both extremes are desirable in different musical situations. Both would place the sound at different distances, and each would cause the sound source to be heard differently in the same mix—one would more likely be prominent in a musical texture than the other.

How sound sources “sound” is an important aspect of recordings. Models of instruments and specific performers have their own characteristic sound qualities. Sound qualities are matched to musical materials and the desired expressive qualities to create a close bonding of sound quality and musical material. For instance, the opening of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” would sound very different on a Hammond organ than on the Lowrey of the recording. A listener would recognize something incorrect about the source, even before they might identify the sound quality as being different. That musical idea is forever wedded to that original sound quality.

Figure 10-8 Distance location graph for The Beatles’ “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.”

Great insight into productions can be found through an evaluation of all of the artistic elements in a particular recording/piece of music. This process will allow the listener to explore, in great depth, the inner workings of all sound relationships of a recorded piece of music. The listener would benefit from performing this exercise on a number of pieces, over the course of a long period of time. Not only will the listening and evaluation skills of the listener be refined, if recordings are carefully chosen, these evaluations will also provide many insights into the unique production styles of certain engineers and producers, as well as an understanding of the artists’ work.

The project of performing a complete evaluation of a piece will be lengthy. It will take the beginner many hours of concentrated listening. The demands of this project are, however, justified by the value of the information and experience gained. This project will develop and refine critical and analytical listening skills in all areas.

For greatest benefit, an entire work should be evaluated. The listener should be mostly concerned with evaluating all of the artistic elements. An evaluation of the traditional musical materials and the text might be helpful as well but is not necessary for most purposes. Upon an evaluation of the artistic elements individually, the listener should evaluate how these aspects relate to one another, and how they enhance one another.

This complete analysis of an entire recording is strongly encouraged. Many aspects of a recording will only become evident, when evaluations of several artistic elements are compared with one another, and compared to the traditional musical materials. The use of the artistic elements in communicating the musical message of the work will become much more apparent, when their interrelationships are recognized.

The listener will compile a large set of data, in performing the many evaluations of Chapter 6 through the pitch density of Chapter 10. These many evaluations will represent many different perspectives and areas of focus.

Some of this information will be pertinent to understanding the musical message of the work, and some of the information will pertain to its elements of sound (such as how stereo location is used in presenting the various sound sources). Also, some of the information will be pertinent to appreciating the technical qualities of the recording. All of this information will contribute to the audio professional’s complete understanding of the piece of music, of how the piece made use of the recording medium, and of the sound qualities of the recording itself.

The sequence of evaluations that may prove most efficient in evaluating an entire work (depending upon the individual work, it may vary slightly) is:

• |

List all of the sound sources of the recording |

• |

Evaluate the pitch areas of unpitched sounds |

• |

Define unknown sound sources and synthesized sounds through sound quality evaluations |

• |

Create a time line of the entire work |

• |

Plot each sound source’s presence against the time line |

• |

Designate major divisions in the musical structure against the time line (verse, chorus, etc.) |

• |

Mark recurring phrases or musical materials, similarly, against the time line; an in-depth study of traditional musical materials would be appropriate at this stage, if of interest |

Evaluate the text for its own characteristics and its relationships to the structure of the traditional musical materials, as appropriate |

|

• |

Perform any necessary melodic contour analyses of those lines that fuse into contours |

• |

Determine reference dynamic level |

• |

Perform a program dynamic contour evaluation |

• |

Perform a musical balance evaluation |

• |

Perform a performance intensity evaluation |

• |

Evaluate the work for stereo location or surround location |

• |

Evaluate the work for distance location |

• |

Perform environmental characteristics evaluations of all host environments of sound sources and the perceived performance environment |

• |

Create a key of the environments to evaluate space within space information |

• |

Perform a pitch density evaluation of the work |

• |

Study these evaluations to make observations on their interrelationships and to identify the unique characteristics of the recording |

The following materials may be coupled on the same graph (on separate tiers), or on similar graphs. They are all at the same perspective (at the level of the sound source):

• |

Performance intensity |

• |

Musical balance |

• |

Distance location |

• |

Stereo location or surround location |

The above four artistic elements will be interrelated in nearly all recording productions. Observing the interrelationships of these elements will allow the listener to extract significant information about the recording. In making these observations, the listener will continually formulate questions about the recording and seek to find solutions to those problems.

The questions of how artistic elements (and all musical materials) relate to one another will center on:

Music is constructed as similarities and differences of values and patterns of musical materials. This is also the way humans perceive music. People perceive patterns within music (its materials and the artistic elements). Listeners will perceive the qualities (levels and characteristics) of the elements of the music and will relate the various aspects of the music to one another.

At the same time, the listener should compare what they are hearing with what was previously heard, and to their previous experiences. Meaning and significance will be found in this information by looking for similarities and differences between the materials.

The listener should ask, “what is similar” between two musical ideas (or artistic elements); “what is different;” “how are they related?” These will be answered through observing the information that was collected during the many evaluations. The shapes of the lines on the various graphs may show patterns. The vertical axes of the graphs may show the extremes of the states of the materials and all of their other values.

The listener’s ability to formulate meaningful questions for these evaluations will be developed over time and practice. They will be asking: “what makes this piece of music unique,” “what makes this recording unique,” “how is this recording constructed,” “how is this piece of music constructed,” and “what makes this recording effective?” Many other, much more detailed questions will be formulated during the course of the evaluation. The listener should finally ask, “which of these relationships are significant to the communication of the musical message; which are not?”

The use of the artistic elements in the recording can also be considered in their relationships to the traditional musical elements and materials. This brings an understanding of the importance of each musical idea, as related to the piece as a whole. Through these observations, the recordist will obtain an understanding of the significance of the artistic elements to communicating the message (or meaning) of the music. The recordist can then understand and work to control how the recording process enhances music, and how it contributes to musical ideas and the overall character of the piece.

This entire evaluation process will greatly assist the recordist in understanding how the artistic elements may be applied in the recording process to enhance, shape, or create musical materials and relationships.

The recording production styles of others can be studied and learned. By understanding the sound qualities of a recording and being able to recognize what comprises those sound qualities, the sound of another recording or type of music can be emulated by the recordist in their own work as desired.

Graphing the artistic elements may be time consuming, and at times tedious and perhaps frustrating. The graphing of the activity of the various artistic elements is important, however, for developing aural skills and evaluation skills, especially during beginning studies. It is also valuable for in-depth looks at recordings; providing insights into the artistic aspects of the recordist’s own recordings and the recordings of others.

This process of graphing the activity of the various artistic elements is also a useful documentation tool. Graphs can be used to keep track of how a mix is being structured, or how the overall texture is being crafted. Many of the graphs or diagrams can even be used to plan a mix. For example, the imaging diagram can be used to plan the distribution of instruments on the sound stage and consider distance assignments before beginning the process of mixing sound—perhaps even before selecting a microphone to begin tracking. Working professionals through beginning students will find these useful in a variety of applications.

Graphing artistic elements is not proposed for regular use in professional production facilities and projects. The graphs are not intended for the production process itself. Audio professionals must be able to recognize and understand the concepts of the recording production, and hear many of the general relationships, quickly and without the aid of the graphs. The graphs are intended to develop these skills, and to provide a means for more detailed and in-depth evaluations that would take place outside of the production process.

Recordists who have developed a sophisticated auditory memory will also find these graphing systems of evaluation to be useful for notating their production ideas, and for documenting recording production practices. These acts will allow them to remember and evaluate their production practices more effectively, allowing them more control of their craft.

All of the exercises presented in the text are listed at the beginning of the book after the Table of Contents. The exercises are ordered to systematically develop the reader’s sound evaluation and listening skills. Working through the exercises in this order will be most effective for most people. Readers with much experience and well-developed skills will still find at least a few exercises that are sufficiently advanced to test and improve their skills. Learning anything new requires effort and a willingness to reach into the unknown. Very sophisticated listening skills are required in audio and music. Developing such skills from the beginning will take practice, patience, and perseverance. At times the listener will be told to listen to things they have never before experienced. They will have no reason to believe such sound characteristics even exist, let alone can be heard, recognized, and understood. Faith will be required; a willingness to be open to possibilities and leap blindly into an activity, searching the sound materials for what they have been told exists.

Following the system will give the listener a refined ability in critical and analytical listening. The listener will learn to communicate effectively about sound, and be able to apply this new language to many situations.

Among other things, Part 3 will explore how these new listening skills and knowledge of sound can enhance the recordist’s ability to craft recordings.

Pitch Density Exercise.

Select a recording with four to six sound sources, to graph the pitch density over the first two major sections of the work. The recording should contain pitch density changes within and between sections.

The pitch areas in pitch density are determined in a similar way to defining the pitch areas of nonpitched sounds. The material being plotted is more complex, however, and the process more involved.

The musical texture must (1) be scanned to determine the musical ideas present. The musical ideas might be a primary melodic (vocal) line, a secondary vocal, a bass accompaniment line, a block-chord keyboard accompaniment, and any number of different rhythmic patterns in the percussion parts. The number and nature of possible musical parts are limitless.

The musical ideas must (2) then be clearly identified with the sound source or sources performing it. This may be a simple process, or not. It is possible for a single instrument to be presenting more-than-one musical idea, such as a keyboard presenting arpeggiated figures in one hand and a bass line in another. It is possible for many instruments to be grouped to a single musical idea, then suddenly to have one instrument emerge from the ensemble to present its own material. The possibilities are much more complex than merely labeling each musical part with the name of an instrument, although this is often the case.

Each idea will (3) then have its pitch areas defined by a composite of the pitch area of the fused musical material, and the primary pitch area of the instrument(s) or voice(s) that produced the idea.

The process of determining pitch density will follow this sequence: