5

How to Fight with Love

I want you to know I have been holding your hand through this journey. I have been right there beside you as you’ve wrestled and pinned down your own fears and stood up to the bullying belief that somehow you were not enough. My ability to scale the mountainous task of writing an entire book about radical self-love has demanded I see you, not as some anonymous form, but truly see you, in your body, reading this book as the tremors of your own divine enoughness began to crack the ground of body shame around you. We need each other for this journey to be possible. Isolation is not solitude nor is it radical self-love. When we are connected to our own divine power, we become connected to all. That includes every other person who picked up this book and endeavored toward this work as well. The most transformative element of radical self-love is its ability to extend beyond our individual experience. You are not only reading this book to heal your own fraught relationship with your body. You are reading this book because you are called to pick up the needle and thread and add to the repair of our gorgeous but painfully tattered collective humanity. Together we can create a web of love, both energetic and material, psychological and physical. You have already begun weaving and it has imbued you with the planet-shifting force to fight a world of body terrorism through the transformative act of love.

Radical Self-Love Transforms Organizations and Communities

I propose that it is impossible to interact with radical self-love and remain unaltered. Once we are reconnected to our own radical self-love anchor, we start to register body-terrorism threats far more quickly. Our awareness of how body shame and body terrorism operate in our lives, families, communities, workplaces, and governments becomes acute and uncomfortable, like lying on a bed of body-shame cacti. It is this discomfort on a community and organizational level that motivates structural change. In publishing this book, I had the opportunity to see firsthand how a radical self-love framework pushes an organization out of their corporate comfort zone and into the realm of the radical. This sort of organizational shift is essential if we want to bring about long-term systemic and structural change.

Berrett-Koehler Publishers is the awesome midsized independent publishing house who brought you this book. Based in Oakland, California, their mission is “connecting people and ideas to create a world that works for all.” We were clearly cosmically suited for one another, and I was an enthusiastic YES when they approached me about writing a book on the work of radical self-love. Berrett-Koehler’s commitment to being equitable, fair, and focused on positive change was beautiful. But beautiful is not necessarily radical. Somehow encountering the radical self-love message always seems to plant seeds whose fruits come to bear, often unexpectedly.

The humans working to bring the TBINAA book to life were as diverse as my former poetry slam team all those years ago. Jeevan, a tall, Brown, South Asian man with whom it appeared I had as much in common as a watermelon has with a wombat, was assigned as my editor. He was patient as the winds of imposter syndrome whipped me into a ball of worry and procrastination. Although kind, he was not yet a radical self-love convert. “The truth is . . .” Jeevan confessed, “I wasn’t sure I even agreed with her—it was too easy to dismiss her (initially) as yet another ‘fat-positive’ person who was trying to force others to support something that was flawed, unhealthy, and making excuses for just poor life choices. I did agree to work on the book, though, because someone whom I respect deeply told me once that every editor should work on books he or she disagrees with, because to do otherwise was unacceptable to our role as disseminators of a truly wide spectrum of ideas.”

Many of us start off like Jeevan, skimming the surface of radical self-love based on our preconceived notions and historical biases. We treat new ideas like we treat bodies, dismissing what we can’t understand, what we view as too different. Luckily for me, Jeevan’s job description demanded that he get below the surface of this radical self-love concept. What he discovered lying at the bottom of his own ocean floor was a history of disordered eating, stories of body shame he harbored against himself, and judgment he aimed at others. Months after the book went to print, Jeevan shared the following with me:

Working on this book impacted me more deeply than almost 95 percent of all the books I have ever worked on (keeping in mind that I have indirectly and directly been involved to some level in over 400 books by now). This book is not about something as simple as body positivity or acceptance. It is about the ways in which we see others and ourselves and judge one another on far deeper levels than we may know because at the heart of it all, even the deepest-held beliefs begin with the most superficial and perfunctory glances and barely conscious judgments. The deepest convictions we hold and the ways in which we interact and treat one another are often put in place there by the seemingly most superficial of assessments—those of others’ bodies and our own.

Jeevan had awakened to how radical self-love might heal us from these barely conscious judgments. He began to see how its properties might act as a salve on the many other oppressive afflictions plaguing our world. What Jeevan didn’t know was that he was about to slather a heap of radical self-love on his whole workplace.

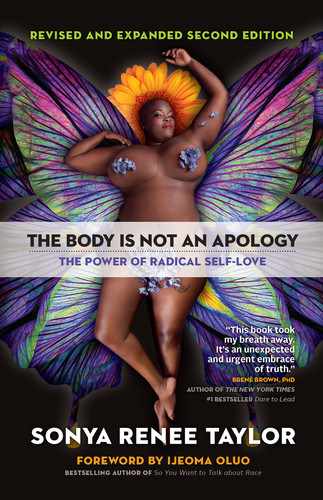

Everyone’s radical self-love boundaries were pushed wide open when it came time to pick a cover for this book. I’d walked into the planning meeting toting a laptop folder full of meek and mild Pinterest images and color themes meant to evoke feelings of freedom, love, and connection. I was not thinking radically. But when I cursorily flashed the image of my naked body sprawled against a background of purple hydrangeas, the room audibly gasped. The picture was one in a series of photos titled “American Beauty” that featured trans and cis women of different ethnicities, body sizes, and aesthetics re-creating the iconic scene from the 1999 film of the same name. Photographer Carey Fruth’s viral photos snatched beauty back from the singular American thin, blonde, young, White, cis-gendered ideal and placed it on a fat, dark-skinned, bald Black woman.

“That is the cover, Sonya,” Jeevan pronounced to the conference room of staff.

“Umm, Jeevan, I really am not prepared to be naked in Barnes and Noble,” I shot back.

“Sonya, this photo is what this book is saying. That it is okay to be you, in your body, even if that body is naked.”

“But it’s not about me. I don’t want people to see a fat Black woman on the cover and decide not to buy the book,” I retorted. There, as naked as my book cover, were the boundaries of my own radical self-love: the fear that my body would mean rejection. Even if I didn’t see my body as wrong, what if the world did? My editor had resurrected my original hypothesis. Either my unapologetic image would imbue others with the power and permission to be unapologetic in their bodies or I would be judged, rejected, shrunk down, and contained. The only way to know was to broaden the potential of radical self-love and see if others could withstand the pressure.

Once my scantily clad cover was released for feedback, Berrett-Koehler’s boundaries were tested as well. Amid the emphatic affirmations for the cover were also “concerns” that the images might be seen as pornographic or erotic. Marketers said they would have to deliver the book in black plastic as “adult content” with reps in Brazil, proposing the image was too racy. Yup, BRAZIL! When Berrett-Koehler higher-ups expressed concern that the image might be objectifying and sexualized, Jeevan responded like a budding radical self-love scholar pointing out the double standard in the perception of my dark, large body compared to other book covers showcasing naked thin White women. He even identified how it is not men’s roles to tell women, and in this case women of color, whether or not they are being objectified and encouraged men in the company to listen to the perspectives of women of color.

Berrett-Koehler put the Three Peaces into practice in order to bring this book to the world. The team had to make peace with my different body on the cover and the necessity for a different creative process to bring this book to market, honoring that the message of radical self-love demanded more than standard operating procedure. Secondly, they had to make peace with not understanding and allowing others to not understand too. Not every team member or partner would get why I needed to be naked on the cover of the book and nor did they need to in order to bring this project to fruition. The organization did need to trust the judgment of the team members who did understand. By choosing to raise to prominence and listen to the voices of women, and specifically women of color, on this project, Berrett-Koehler decentered the default bodies in their organization and relinquished the need to control the process, creating space to trust that there were simply parts of the journey they would not understand—and that it was not something to fear.

Lastly, Jeevan’s journey of making peace with his own body and reflecting on how he’d spent so many years apologizing helped him shepherd his organization through the Three Peaces. His own radical self-love journey became the foundation for his organizational advocacy. Others followed suit and encouraged even deeper reflection and through the collective process brought about company-wide shift in perspective. I’d like to think Berrett-Koehler is getting a bit more radical by the day.

Freedom Frameworks for an Unapologetic Future

It bears repeating again, this book does not propose that razing body shame and body terrorism in ourselves or out in the world is easy. If it were, I’d be on to my horticulture career by now. Unfortunately, there is an ultimate warrior obstacle course of barriers we must circumnavigate to effectively transform a world run by the Body-Shame Profit Complex into a world that supports our diverse and divine bodies. Luckily for us, a plethora of brilliant and beautiful humans have lent their light as guidance on the path. They are the candle keepers, friends and peers whose wisdom offers consistent direction on the pathway toward a just, equitable, and compassionate planet for each of us.

Pleasure activist, doula, and social-justice facilitator adrienne maree brown’s work puts us in powerful conversation with two essential elements in creating a radical self-love world: the power of emergent strategy and the radical power of pleasure. In her book Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds, adrienne maree brown identifies how the simple interactions of the natural world offer us insight into myriad possibilities for collective social change. She puts forth a series of principles that undergird the framework of emergent strategy. Her ninth principle holds the full intention of this radical self-love work in its simple offering: “What you pay attention to grows.”1 If our collective focus becomes love and the notion that every human being in every imaginable form deserves a world where they can love and be loved in the bodies they have today . . . and if the definition of love is one that includes resource, care, compassion, justice, and safety for all bodies, just imagine what we might grow together!

Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s work as a queer, disabled femme of color continues to bring to the center the stories, lives, and needs of queer, sick and disabled, BIPOC bodies. In her book Care Work, Leah illustrates how sick and disabled folks practice radical love by celebrating the networks of care their communities have cultivated throughout history for survival. She makes visible how the imperfect but innovative organizing of sick, mad, neurodivergent, crip, d/Deaf, and disabled folks of color continuously challenge systems of body terrorism beyond ableist binary notions of sad or “inspiring.” Leah reminds us that the disability community has been one of our most enduring examples of what it means to leave no body behind and that care work and radical self-love are inextricably bound. She offers:

Love is bigger, huger, more complex and more ultimate than petty fucked up desirability politics. We all deserve love. Love as an action verb. Love in full inclusion, in centrality, in not being forgotten. Being loved for our disabilities, our weirdness, not despite them. . . . Love gets laughed at. What a weak, non-political, femme thing. Bullshit, I say. Making space accessible as a form of love is a disabled femme of color weapon.2

Leah and adrienne are two of hundreds of humans I watch in real time embodying a radical self-love praxis through new and existing frameworks. Radical self-love, disability justice, emergent strategy, and pleasure activism are unique dialects for a co-manifested world brimming with the abundant opportunities, access, and resources any of us may need to evince our divine purpose, whatever that may be. Leah’s essay on making space accessible as an act of love was written the same year I wrote the poem “The Body Is Not an Apology.” Perhaps we were all being simultaneously directed to add to the elixir of radical healing needed to actualize a new unapologetic future for us all. You are also being called to add to the brew.

Fighting Oppression, Isms, and Phobias

Together we have examined how the systems of body shame and body terrorism live in us and how we might demolish them from the inside. Radical self-love starts with us but was never meant to end there. The internal practice is for the purpose of envisaging a new world order guided by love. How we get there requires we fight the systems of body shame and hierarchy individually and interdependently, both committing to personal accountability and lending strength to the collective battle against body terrorism. In the remaining pages are strategies, candle keepers, and radical self-love warriors to follow and organizations to support with your money and time. To fight such deeply ingrained systems we must be willing to do both internal and external work, working on our indoctrinations and working with others to further the initiatives and efforts that have long been pushing for justice, equity, and systemic change. As Leah reminds us, we will need the most powerful weapon in human history . . . love.

Fighting Fatphobia

Fatphobia remains one of the most challenging forms of body terrorism to beat back. The multibillion-dollar weight loss and diet industry has figured out how to squeeze into every crevice of our lives more effectively than a pair of Spanx, using fear, shame, and a coopted “body positivity” to sell us more deceptively marketed fad diets through fatphobic narratives of “getting healthy” and “lifestyle” changes. From corporate, employment, and immigration discrimination against fat people to the erasure and gaslighting of fat people daily in doctor’s offices, our bias against fat is consistently wreaking personal, professional, and structural terror on fat people’s lives. Research repeatedly shows that weight stigma and bias lead to ongoing substandard care by medical professionals. Lifesaving diagnoses go undetected and vital care is often refused to those with fat bodies.3 Couple this reality with medical bias against women, trans and gender-nonconforming folks, and people of color and imagine what the medical experience of a fat trans woman of color might be like (cue the intersectional analysis). Fat is not the problem; fatphobia is what is deadly.

How can we fight fatphobic body terrorism? As with all radical self-love change, we must start with us. The recipe is simple (though not easy): explore and challenge our assumptions (thinking), shift our actions (doing), and develop an emanating self-love practice (being). Using our thinking, doing, being approach, we can challenge fatphobia in ourselves and call in others to do the same.

Thinking

Strategy 1: Embrace Shame-Free Inquiry

There is no better place to start than to get curious about what we currently believe and how we may be operating as unwitting agents of body terrorism. Shame is a big burdensome iron bar that will keep you from your curious quest before you even begin. Be inquisitive and loving rather than harsh with yourself and your answers. Remember, you are not bad or wrong—you’re human.

Below are questions to help you explore your thoughts and beliefs about fat bodies:

- Do I believe it’s okay to be bigger, just not too big? How do I define “too big”?

- Do I make assumptions about people’s health based on their weight?

- Do I believe “healthier” bodies are better bodies?

- Do I use the word fat pejoratively to describe myself or others (including internal dialogue)?

- Do I believe being fat is fine for others, just not for me?

- Do I believe fat people could lose weight if they just tried hard enough?

- Am I afraid of becoming fat?

- Do I dislike my own fat?

If you answered yes to any of these questions, you have some internalized fatphobia to work on. Here’s the good news . . . of course you do! As I mentioned in Chapter 4, it would be a feat of supernatural proportions for you to grow up in a fatphobic society and not have internalized fatphobic ideas. But now that you have raised those fatphobic thoughts and beliefs to consciousness you are ready to step into new action.

Doing

Strategy 2: Make Fat Familiar

We live in a fatphobic culture that assigns default status to thin bodies while labeling all others abnormal, unhealthy outliers. Shake up the paradigm by becoming familiar with the lives and experiences of fat people. Look around your life. Is it filled with smaller bodied people? Are your bookshelves lacking in fat protagonists by fat authors? Who are the fat heroes and heroines on your television? Are they empowered or do they spend their scenes chasing thinness? How about your social media feed? Following any fat folks? If not, today is the day to fatten your timeline. Becoming familiar with the lives of fat people helps to normalize fat bodies and makes us all more aware of what they traverse to survive in a fatphobic world. You are better positioned to challenge fat bias and weight stigma when you have proximity to the lives of fat people.

Listen, fight fatphobic foolishness, but your newsfeed and bookshelf shouldn’t be a Wikipedia of sad, fat lives of discrimination and trauma. Why? Because fat people are thriving in their bodies. Making fat familiar means bearing witness to fat bodies in joy, pleasure, desire, nature, rest, love, movement, and nourishment. Friend, activist, and aptly titled King of the South Jazmine Walker leads a national body movement workshop called “Praise and Twerkship” where she helps Black people reclaim the sensual magic of movement in their bodies. Her Instagram (@jazonyamine) is a visual feast of Jazmine’s morning ritual of twerking and dancing alone in her home. Transformation as magic is watching a fat Black woman from the South cast the spell of her own bounce and rhythm. Jazmine is teaching us to not only accept the fat Black body but to worship it. Taking new action means celebrating the presence of fat bodies more loudly than we applaud the infinite endeavors to shrink our bodies.

Being

Strategy 3: Practice in Public

The practice of new and repeated action is how we step into a radical self-love way of being. To do this, we must practice regularly disrupting fatphobia and weight stigma out loud in our daily lives. If you have spent years on the diet hamster wheel, it is a great day to ditch diet culture and practice a loving, gentle relationship with your body. Intuitive Eating4 and Health at Every Size (HAES)5 are two alternative models moving us away from diet culture and toward providing your body the nourishment and care that is best for you. Both models have principles that turn our attention to our original control center, our bodies, where we can receive the internal cues that lead us to personally defined well-being informed by our unique bodies. Rethink your orientation to food and health. Share your journey with your friends and family to practice in public.

Fatphobia remains one of the most underdiscussed and unacknowledged forms of body terrorism. The allure of thin privilege is frighteningly persuasive; from easy shopping to better job and romantic opportunities, society promotes and rewards thinness and punishes fat. The pernicious lie of fatness as an individual failure of self-control, lack of discipline, evidence of gluttony and laziness all wrapped in a scientifically unsound narrative of health often leads even the most vocal intersectional social justice activists to promote weight loss and advance fatphobic body terrorism. Stomping out fatphobia will mean challenging our friends’, families’, and coworkers’ indoctrination by questioning stereotypes, sharing what we are learning about fatphobia, and asking others to learn with us.

You can start by exploring the racist, classist roots of our societal beliefs about fat bodies by reading Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia6 by scholar Sabrina Strings. Consider alternatives to that family or companywide weight loss challenge by sharing information about intuitive eating and Health at Every Size. Speak up when you see your friends lauding weight loss as achievement and let them know how “before and after” pictures present “before” bodies as wrong and “after” bodies as better. Financially support organizations like the Association for Size Diversity and Health (ASDAH)7 and NOLOSE8 that center the dignity and freedom of fat people. Follow and learn from fat people who are living unapologetically fat lives and promote their work. We all live for Lizzo, and even she would want you to widen your repertoire. Remind everyone that body positivity began as a movement for fat liberation led by and for fat people and must continue to center them. Love fat people out loud and in public and demand others do the same. By joining this fight, you are helping to tear down the bricks of body terrorism one fatphobic idea at a time.

Fighting Ableism

Much like fatphobia and intersectional in its manifestations is our abhorrent social, political, and economic treatment of those living with disabilities, chronic illness, neurodivergence, and other mental health conditions. Under a capitalist system, disabled bodies and differently working brains are difficult to exploit for profit and thus have been framed as bad bodies that should be hidden, pitied, or, as with the eugenics movement, murdered. When they are not met with violence, we use disabled bodies as “inspiration porn,” presenting their bodies as the reason able-bodied people should be more grateful. To defeat an ableist world, we must first look at how we participate in perpetuating one.

Thinking

Strategy 1: Embrace Shame-Free Inquiry

It is easy to point out all of the things wrong with the world. It is a much more uncomfortable and courageous task to look at how we too have been complicit in the maintenance of systems of body terrorism. In a society incredibly adept at harsh and often cruel critique, it is deeply moving to witness one tending to their own culpability with a sense of humility, compassion, and grace. It restores faith in the possibility that perhaps they will extend the same grace and compassion to me. It is from this extension that we often feel safe enough to transform. Get acquainted with how ableism lives in you and your everyday life. Consider the following questions for exploration:

- Do I or have I ever thought about, asked about, or endeavored to learn about the lives of disabled people?

- Do I think about whether my surroundings either at home or work are accessible to those with physical or intellectual disabilities or processing differences?

- Do I have disabled, chronically ill, or neurodivergent people in my personal or professional life?

- Do I assume disabled people hate their bodies? Do I pity them?

- Do I use ableist language like lame, blind, dumb, crazy, insane, nuts, or crippled?

- Have I or do I refer to disabled people as inspiring?

- Would I be ashamed if I had a mental health diagnosis?

Answering these questions helps us assess how commonplace ableism is in our daily lives. Black disability activist Imani Barbarin created the hashtag #abledsareweird to give voice to the barrage of ableist experiences disabled folks are subjected to regularly. Visit the hashtag on Twitter and inventory your own behaviors. If you are able-bodied, it is inevitable that ableist messages have influenced how you perceive disability and illness. Getting into some anti-ableist action is the surest route to divesting from ableism and helping others do the same.

Doing

Strategy 2: Dig into Disability Justice

We can have a world free of ableism, but getting there requires the leadership, guidance, and visionary brilliance of disabled, mad, and chronically ill people. Like most movements for justice, those most impacted have the answers. If we directed our attention and resources to supporting them, we’d be far closer to freedom. The disability justice movement was conceived by a group of “black, brown, queer and trans” people which included leaders like Patty Berne, Leroy F. Moore Jr., Mia Mingus, the late Stacey Milbern, and others involved in the radical disability arts organization SINS Invalid.9 Disenchanted by how the modern disability rights movement too often centered the experiences and needs of White disabled people, this coalition of the marginalized developed a framework to highlight how ableism was intricately woven into racism, queer and trans phobia, and sexism and understood that abolishing one would necessitate abolishing all forms of oppression. Disability Justice offers ten principles to build upon a more inclusive, accessible, and just world for all our bodies. Some of these include:

- Leadership of the Most Impacted: “We are led by those who most know these systems” (Aurora Morales).

- Recognizing Wholeness: People have inherent worth outside of commodity relations and capitalist notions of productivity. Each person is full of history and life experience.

- Interdependence: We meet each other’s needs as we build toward liberation, knowing that state solutions inevitably extend to further control over lives.

- Collective Liberation: No body or mind can be left behind. Only mobbing together can we accomplish the revolution we require.10

Learn and spread the Disability Justice framework. Utilize these principles in your daily life and invite others to do the same. Dismantling ableism means digging into this intersectional, cross-solidarity movement and doing your part to leave no body behind.

Being

Strategy 3: Practice in Public

Taking action against ableism requires actively engaging the perspectives of disabled people of all identities in your life. Read, listen, and watch media that centers disabled lives not as feel-good stories for able-bodied folks’ consumption but as works that present disabled people in the full complexity of their lives, made for and by them. Challenge casual ableism by asking about accessibility in the places you frequent. Interrupt the ableist language you use and enroll others in doing the same. Invite those you love to be part of raising awareness and action to be in greater solidarity with disabled communities. Similar to fatphobia, activist spaces often erase the needs of the disability community, fighting for the rights of LGBTQIAA+ and/or people of color, while forgetting that many of those people are or will be disabled. Activism absent of the voices and vision of disabled people cannot be radical. Disabled people should be part of the leadership and planning of our work, and if they are not we must ask why.

Queer, fat, disabled TBINAA staff writer Nomy Lamm suggested we add access needs to our digital staff meeting check-ins alongside our names and pronouns. Team members were given time to consider what they needed or what the team should know to aid in their fullest participation in the meeting. A teammate had chronic pain and said they would need to step away to stretch during the call. Another shared how their depressive episode was impacting their information processing and might need folks to repeat themselves. Others had sensory processing challenges and asked that we type in chat so they could be on mute and still participate in the meeting. Some people had no access needs in April but needed support on the call in May. Through this practice we normalized access needs by making space to consider them and ask for support. At some point all humans will have access needs. Practice identifying them and asking for them to be met. Are you a visual learner who’d benefit from someone writing down what they are saying on flipchart paper? Maybe you feel claustrophobic and need a door to be opened during the meeting? Perhaps you have chemical sensitivities and need people to refrain from using perfumes and chemical fragrances? Much like wheelchair spaces, ramps, and ASL interpreters, these too are access needs. When we normalize access needs, we destigmatize difference, carving out space for invisible disabilities and illnesses in our communities. This is how we interrupt the abled body as the default body. Practicing in public means making disability part of how you think, live, and love in the world and asking friends, family, community, and your workplace to join you in doing the same.

Fighting Queerphobia and Transphobia

Our indoctrination into cis- and hetero-centrism begins before we are even born. From gender reveal parties to color-coded baby showers, society compels our allegiance to strict gender and sexual roles before our first breath. Those who fail to comply with our default assumptions of gender as male or female and sexuality as attraction to the opposite gender are maligned, erased, and, throughout history, killed with little recourse. We have constructed our social, political, and economic systems to value cisgender people—those who identify with the gender they were assigned at birth—and privilege them in ways that go unnoticed. The reality for a disproportionate number of queer, trans, and gender-nonconforming people globally is that of unrelenting body terrorism, with even higher rates for queer and trans Black, Indigenous, and people of color (QTBIPOC).

Thinking

Strategy 1: Embrace Shame-Free Inquiry

From a place of curiosity and compassion, explore how you have made cisgender and heterosexual identity the default in your life. Consider the following questions:

- Do I make assumptions about people’s gender based on what they are wearing or look like?

- Do I assume people’s gender without asking them, using he or she pronouns based on only my assessment?

- Do I have transgender people in my personal or professional life?

- When I meet married people, do I assume their partner is of the opposite gender?

- Do I follow, read, or watch content created by LGBTQIAA+ people?

- Do I use gendered terms like “ladies and gentlemen” when speaking?

- Do I equate being a woman or a man to genital or reproductive body parts?

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, intersex, asexual, agender, pansexual, polyamorous, kink, two-spirit . . . if you read this list and feel overwhelmed, imagine what it might be like to spend most of your life being invisible in film, television, radio, schools, jobs, and so on. When you are represented, it is to provide stereotypical comic relief, sensationalism (see Jerry Springer), or mockery. In fact, there are infinite arrangements for how we experience or don’t experience attraction, desire, and understand our gender. Still we scoff at the rolling out of so many letters, never questioning who we have been erasing and shrinking into a dry binary default. A world free of queerphobic and transphobic body terrorism obligates us to look at our own privilege and investment in only considering the default bodies of cis and straight people.

Doing

Strategy 2: Queer Your Life

Black Canadian poet Brandon Wint’s viral quote offers a foundation upon which to begin queering our perspectives with a new radical definition of queer. “Not queer like gay. Queer like, escaping definition. Queer like some sort of fluidity and limitlessness at once. Queer like a freedom too strange to be conquered. Queer like the fearlessness to imagine what love can look like and pursue it.”11 Brandon’s quote helps us reconceptualize queerness, expanding it beyond the boundaries of sex and desire, moving it into the realm of the uncontainable. If radical self-love is an act of becoming difference celebrating then pursuing a “freedom too strange to be conquered” is right up the radical self-love alley. In order to compost12 homophobia and transphobia into the rich soil of radical self-love, we must begin to challenge the subtle and not-so-subtle ways it governs our world.

Get intimate with the lives and struggles of queer and trans people. It’s tempting to assume that the visibility of Caitlin Jenner and the achievement of same-sex marriage of cisgender people means we have solved homo- and transphobia. But visibility and the legal right to marry are both privileges afforded those with the most access and other intersecting default identities, such as Whiteness or wealth. Media would make it appear that the transgender community sprouted overnight. What the Western world understands as transgender identity has been around throughout history,13 and the term transgender is a Western conceptualization we have created to make sense of expanded gender identity beyond the constraints of a binary. Other cultures have long had members of their societies who have lived outside the confines of simply male or female, and our efforts to interrupt body terrorism demands we queer our understanding of gender.

Also paramount to queering our lives is learning about the lives of the contemporary trailblazers who forged a path for queer and trans rights, including the names and histories of folks like Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, two trans women of color who were instrumental in the Stonewall uprisings—the resistance protests that sparked the gay rights movement14 on Turtle Island (U.S.). Raise attention and awareness to the alarmingly high rate of murders of Black and Latinx trans women and explore the connection between their mortality and society’s discriminatory and violent treatment of trans people. Support, promote, and resource action and acknowledgment days like Transgender Day of Remembrance.15 But do not stop there. Ask tough questions like, “Would we need a Transgender Day of Remembrance if we practiced vocally celebrating and creating access and resource for trans and gender-nonconforming people in the present?” Queering our lives means challenging heterosexuality and cisgender identity as superior or normal ways of being. As we continue to center the lives of queer and trans people, inevitably we do exactly what Brandon proposed: we become cocreators of a “freedom too strange to be conquered.”

Being

Strategy 3: Practice in Public

Social change is not automatically tied to personal change. Nice as it would be, it is not a given that the systems of body terrorism will instantly dematerialize just because we become less harmful to ourselves and those around us. Nope. We must use our newfound power to communally push those systems down with organized, collective action. Some of our efforts will be small and interpersonal, like interrupting queer and transphobic stereotypes we hear from friends, family, or coworkers. And other efforts will need to target structural and systemic issues.

In a system that devalues the lives of queer and trans people and to an even greater extent queer and trans Black, Indigenous, and people of color, organizations created and led by the QTBIPOC community are often the most underfunded and under-resourced Using our dollars to help support communities carving out lives of dignity and respect in the face of constant body terrorism is a necessary radical self-love practice and an act of best-interest buying. Following their leadership and guidance and encouraging others to follow suit helps build those organizations’ capacity and further their impact. Show up and volunteer at an LGBTQIAA+ youth center, and support queer- and trans-led media, music, and content. Support the basic needs of someone in the queer and trans community who is struggling, perhaps by contributing to their crowdsourcing campaigns. These are all personal actions that strengthen the collective, but you can and should also act in advocacy in places where you have privilege. You can disrupt the binary default at work by sharing your gender pronouns and asking your coworkers to share theirs, even if—especially if—you assume everyone is cisgender. Ask your employer about their hiring practices and whether or not they have considered if the workplace is queer and trans inclusive. If it is not, push for equity and inclusion initiatives at your organization. Be sure to do this before you begin inviting queer and trans people into hostile work environments. Challenge queer and transphobic legislation by writing your government representatives and keeping abreast of local and national bills that might affect the lives of the queer and trans people most often left behind. Practice in public asks us to put our individual and collective efforts toward creating a just and generous world for trans and queer people. Until all of us are free, none of us is free.

Fighting Racial Inequity

In Chapter 2, we discussed how the notion of default bodies shapes how we perceive our own bodies and impacts the experiences of all human bodies. In Chapter 4, we explored how body terrorism builds structures and systems that privilege default bodies and marginalize bodies of difference. Some of the most pervasive, violent, and longstanding forms of body terrorism are racism, White supremacist delusion, and racial inequity. There are reams of books, workshops, podcasts, speaker talks, and films to help you understand and unpack how racism—and specifically White supremacist delusion—impacts the world and the lives of people of color. I won’t reinvent the wheel when so much genius currently exists in this area. There are, however, a few vital points I believe will help us all as we strategically work to rid the world of racist White supremacist body terrorism.

Thinking

Strategy 1: Equity above Equality

Abolishing racism means that we must be fear-facing and examine our complicity and indoctrination. We’ve been complicit—not out of malice but because we have been groomed and raised in a system of racial injustice that has relied on our obliviousness and/or apathy to maintain its uninterrupted operation. You may notice that I did not use the term racial inequality to describe the outcomes of racism in our society but instead chose racial inequity. Equity and equality achieve significantly different ends for those who experience and live with the impacts of racism. Equality means providing the same opportunities or levels of support to everyone—a well-intentioned practice on the surface. But if we peel back a layer we can see how the guise of equality can spread inequity like a brush fire. Consider you were hosting an eight-month-old baby, an eighty-five-year-old woman, and a twenty-two-year-old man for dinner tomorrow night (I know it’s weird to host a baby for dinner, but bear with me). Would you feed them all a roast lamb entrée? How about a single tall glass of fresh breast milk? My hunch is you would know that each of these humans needs considerably different options for their very different bodies. Feeding them equally in amount or type of food would not be an act of truly caring for any of them. Equity proposes that we give people what they need to best meet their unique circumstances. Equity acknowledges we have varying needs and seeks to provide resource and opportunity based on what will help us achieve the best outcomes based on our specific circumstances.16 Racial equity honors how histories of racism, White supremacist ideologies, slavery, and colonization have altered the playing field, leaving many racial groups to navigate issues that demand a different set of solutions. Working toward racial equity may mean releasing our outdated notions of fair and working toward creating systems and structures that are just.

Doing

Strategy 2: Wake Up to Racism and White Supremacist Delusion

In most of the Western world and nations impacted by colonization, bodies that are coded as “White” are given default status and the privileges and systemic power of said status. People of color, whether they be Black, Latinx, Indigenous, Asian, Middle Eastern, Pacific Islander and all others, have been systemically discriminated against globally, resulting in disparate outcomes in wealth, health, education, and most other social markers of capitalism.

In Ijeoma Oluo’s book So You Want to Talk about Race, she explains why it is useful to define racism as the experience of race-based prejudice plus the power of a system that codifies those prejudices under misleading, neutralized terms (recall our discussion of color blindness).17 If you are reading this book, I’m going to venture that you are not a neo-Nazi. Which is great, but you don’t need to be a neo-Nazi to help the system of White supremacist racism carry on. You simply have to do nothing, and the powerful mechanisms of racial body terrorism will continue to operate with relative ease and efficiency.

If you are White or present as White, like it or not you will receive benefits from society because of your racial identity. The most effective way to ensure no one else ever gets the benefits you get is to never question why you get those benefits. In the fourteen-part podcast series Seeing White, hosts John Biewen and Chenjerai Kumanyika carry listeners through the inception, codification, and proliferation of White identity as default, embarking on an ocean-deep exploration into how Whiteness came into being, from the invention of the mythical race science to its accumulation of power.18

Unfortunately, White supremacist delusion has not only shaped how White people operate around race. It has shaped how people of color see, understand, and experience themselves and other communities of color. Global anti-Blackness, the Asian model-minority myth, colorism, xenophobia, and Islamophobia are all fueled by the toxic outgrowths of the internalized White supremacist narratives BIPOC hold about each other. By divesting in White supremacist narratives of fearing otherness, we can reinvest our time in learning about the struggles, lives, and liberation stories of other people of color. It is in our solidarity that we can topple the system of White supremacist delusion.

Being

Strategy 3: Muscle Up and Join In

If you live in a privileged body, it’s likely you have not been forced to think about the blinders of privilege. Society allows your default body to exist without considering the ways in which that default status impacts others or, for that matter, impacts you. White people are rarely asked to think about their Whiteness. Consequently, when people of color discuss the weight of racial injustice, it is often White people who buckle in guilt, shame, denial, minimization, and any number of other tactics to avoid accountability. This avoidance is not only gaslighting and exhausting for people of color, it simultaneously robs White people of the opportunity to explore and interrupt the ways they assist in propping up the system of White supremacy. This atrophied racial muscle is called White fragility, a term coined by academic and author Dr. Robin DiAngelo. White fragility contextualizes the discomfort and defensiveness White people display when confronted with the realities of White supremacist racism.19 Dismantling the edifices of White supremacist delusion will require that White people build intellectual and emotional resilience in matters of race. It’s time to develop a radical racial workout.

Despite their best efforts, White people will never be the most proficient at identifying the machinations of White supremacist delusion any more than subjects in a picture would be adept at pointing out the details of the frame. As is frequently noted, it is not the job of people of color to explain racism to White people. Yet people of color have generously provided exhaustive, nuanced, and detailed resources in the form of scholarship, literature, film, television, music, visual art, providing an ark of resources to help White people abandon the ideology and artifices of White supremacy. One such act of gift is author Layla Saad’s Instagram challenge turned workbook turned New York Times best-selling title, Me and White Supremacy. Saad offers readers a twenty-eight-day workbook to explore how White supremacy intersects and influences White people’s lives, asking readers to confront anti-Blackness, appropriation, power dynamics, and more.20 The more we each explore and become accountable to our role in these systems, the wider the circle of transformation becomes.

A broad coalition of humans of all races have always worked in solidarity to halt the impacts and decimate the structures of racial injustice. From Dolores Huerta21 to Yuri Kochiyama,22 to the Polynesian Panther Party,23 humans en masse have aligned their energy and resources toward the goals of equity and justice. If you’re committed to radical self-love as a social justice practice, you will need to do the same. Organizations like the Movement for Black Lives, United We Dream, Showing Up for Racial Justice (SURJ), Sister-Song, Indigenous People’s Power Project, South Asian Americans Leading Together (SAALT), and Race Forward are plowing a road toward racial equity for their communities. Look them up, support them, join them. As Layla Saad says, let your efforts help you “become a good ancestor.”

Battling All Body Terrorism

Get Willing to Risk

By no means is this chapter presented as a definitive manual for confronting body-based oppression. Issues of ageism, sexism, and oppressions that intersect with bodily identity like classism or xenophobia all persist and must be addressed, but this book would span the cosmos if I attempted to contain all these issues in these pages. No matter the problem we desire to solve, our work to eradicate all forms of body terrorism will overlap in several strategies. Excavating how we’ve absorbed and parroted the messages of body terrorism against specific bodies and groups of people will help us initiate new ways of thinking. It is this new thinking that urges us to uplift the lives of those outside the default, seeking out and elevating their histories, narratives, cultures, and experiences. By advocating for those in our sphere of influence to join us in expanding our knowledge and challenging our indoctrinated beliefs and ideas about those bodies, we engage new action or what we’ve called doing. And finally, when we join, support, and participate in the existing organized efforts to undo the manifestations of bodily hierarchy and amass our collective power, we destabilize the foundations of body terrorism, weaken its beams, and ultimately collapse its structures, leaving wide-open space to begin a new, loving way of being.

There are scholars, organizers, and activists who believe that interpersonal acts of body terrorism matter little to the larger experience of institutions and systems, proposing that the eradication of these systems is what will most impact the lives of marginalized people. Without question, the systemic manifestations of body terrorism have historically wrought the most significant long-term impacts of harm to those who are oppressed. However, as stated earlier, systems require our active or passive assistance to remain standing. And those consciously or subconsciously invested in and privileged by the system of bodily hierarchy will also have a vested interest in maintaining the present-day order of default bodies. Our individual and consolidated divestment from that system is what makes its continued existence untenable. But creating collective disruption in the system of body terrorism will require each of us to risk.

Change is impossible without risk. Those who live in bodies targeted most by body terrorism are forced to exist in a perpetual state of risk. Whether it be the risk of being misgendered when attempting to access services, like my nonbinary friend Emma, or being targeted for police state violence because of your race, mental health status, or both, like Kayla Moore,24 or being denied employment or fair wages because of a developmental disability like my brother Daryl and sister Jozlynn. To live outside the default body is to be forced to balance upon a tightrope of constant social, political, economic, and bodily risk.

When our bodies are the default, we are asked to risk nearly nothing. We are given a refuge of social comfort in exchange for our compliance to a system of bodily hierarchy. Our barbecues and picnics go undisturbed, our family holiday dinners maintain a placid normalcy. We are afforded an existence of relative ease with those who share our default privilege while nondefault bodies absorb the compounding risks from which we’ve opted out. It is this version of comfort/complicity that we have come to prize over justice. What might become possible if each of us absorbed some of the risk placed on marginalized bodies? What if we refused to be accomplices to body terrorism in all its forms, personal and political?

There are small, everyday ways we are invited to interrupt our collusion with the comfort of body-based oppression in service of justice for all bodies. My opportunity to practice a small act of risk presented itself on a summer day in Aotearoa (New Zealand). A new neighbor, her husband, her friend, and I sat on their porch and watched the sun cast diamond flecks of light on the ocean’s surface at Onetangi Beach on Waiheke Island, thirty miles off the coast of Auckland. We were engaged in simple, comfortable conversation when the topic veered in the direction of body shaming a friend who’d had by their estimation “lots” of plastic surgery. Before I could redirect the conversation away from body shame, one of the women threw out a completely unexpected transphobic comment.

This moment has presented itself a million times a day, in a million different settings, likely since the earliest points of history. Someone makes a comment steeped in the indoctrinations of body terrorism and those who do not agree are suddenly at a crossroad. Do we speak up or do we leave the moment and its default comfort intact? We ask ourselves, “Who am I to disrupt this pleasant day with my politics? What if they think I’m a troublemaker? What if I’m seen as not nice?” Each of us has been conditioned to collude with some form of body terrorism for the sake of preserving the default body’s comfort. Consequently, we give way to continued oppression.

On that porch, I was given the opportunity to choose a budding act of justice over cisgender comfort. Choosing justice did not mean I had to detonate the afternoon with a self-righteous chastising of everyone within earshot. To the contrary, as a person with cisgender privilege it is my responsibility to hold with compassion the deep indoctrination of those with whom I share default status.

My (our) collective assignment is to challenge indoctrinations. There will be times when those challenges must be vociferous and aggressive. And there will be times when our choice to quietly but publicly disavow body terrorism will be the aperture needed to change hearts. On that small porch overlooking Onetangi Beach with a group of people I knew little about other than we shared a default identity of privilege, I made a small ripple in the myopic sphere of cis comfort. I said plainly, “I have some really amazing trans friends. They’re incredibly powerful, beautiful, and important in the world. And that’s who I know trans people to be.” My porch companion stammered, apologized, and we moved on to why body shaming their friend was not going to help their friend love herself.

Each invitation to risk social comfort for an interpersonal act of justice disturbs the social contract of body terrorism. Even a small wrinkle in the bed of privilege is enough to force some of us awake. It is in our awakening that we accrue the collective power to bring into being a transformed world predicated on radical, unapologetic love.