With a full picture of the relationship between features and benefits, we come now to the centerpiece of the canvas: the positioning statement. It’s the geographic center of the canvas but the philosophical center of the strategy process as well.

That’s because, as we’ve said, strategy is, at its heart, a series of choices that define how you’ll focus your efforts. With the Brand Strategy Canvas, you’ve looked broadly outward into the world, then based on your context, added truths to each box that are relevant to your company. You’ve chosen what to include and what to leave out.

In this chapter, you will review each box you’ve already completed and then choose the most powerful thoughts from each box. The result is a single sentence that incorporates all of your insights so far. See Figure 5-1.

This positioning statement distills all the research, insight, and context of a strategy into a single sentence that becomes the foundation for your brand execution.

Then, from that sentence, you’ll dig deeper to uncover a two- to four-word brand essence that sums up your brand, and all your hard work.

To be sure, this is the most difficult part of the process. After all, you have a lot to say about your company and the world it inhabits, so boiling all that down to a single sentence and a short statement will be tough.

But the good news is that all the work you’ve done to this point will guide this part of the canvas, because each box you’ve already completed will serve as a source material for your statement.

Figure 5-1

The positioning statement template

Why a Statement?

There’s a good chance you’ve heard of positioning statements, and it’s possible you’ve even read a blog post or two explaining how to write one.

But why is a statement the main artefact of a positioning exercise? Why not a list or a chart or a diagram?

As you invest your time and energy into developing a strategy, at some point, you’ll want to actually execute and implement the strategy. That implementation will occur over the course of the life of your company, in web site redesigns and product launches, but also through ongoing and seemingly mundane touchpoints, like transactional emails or support requests.

Founders and executives will have lots of input into the more prominent brand executions, like a new web site or logo. But the frontline employees will have countless opportunities to execute your brand strategy in their daily work. Brands can be built, or destroyed, through the many interactions between a company and its audience.

As we’ve discussed, it’s simply not realistic to expect everyone in your company to remember all of the details from your canvas, and it’s even less realistic to expect them to apply all those insights in real time. It’s information overload.

That’s why a primary goal for the brand strategy process is to provide your team with heuristics to use in their daily planning and work.

You want to make things easy on your team by transforming the deep research and key insights you’ve conducted and developed so far into a handful of easy-to-apply ideas or heuristics.

For example, when you head to the market to shop for dinner, you don’t have to remember every step of each recipe you’ve planned for the week. Even more, if you’ve planned well, you don’t have to debate with yourself and reconsider your culinary choices as you stand in the aisles, rehashing with yourself or your partner the choice to make chicken instead of fish.

Rather, you just have to recall the key ingredients that constitute each meal that you’ve chosen ahead of time. In the moment of decision, you just need to focus on what’s essential to drive the outcomes you desire.

That’s why a positioning statement is so handy: it becomes the ingredients list your team can reference whenever they make decisions about your brand.

So how can you make your strategy memorable? Most people have a tough time committing a bulleted list to memory. We’re much more likely to recall phrases or sentences.

Because the positioning statement encapsulates your strategy in sentence form, it will be easy for your teams to recall and apply, providing them with all the crucial ingredients of your brand.

As you appreciate by now, this book is about strategy, not execution, so you won’t use this statement in your marketing materials. Like most of the canvas, it’s an internal tool and a process for sharpening your thinking, challenging assumptions, and making deliberate choices about what matters.

But when it comes time for execution, it will provide you with a short hand for considering your audience and the most important rational and emotional benefits to highlight.

Like the entire canvas, the positioning statement is another powerful heuristic that will help your team execute with quality and consistency.

Positioning Is a Map

There are a few powerful reasons to invest the time and effort needed to craft a positioning statement and brand essence. First, it will serve as the inspiration and guide for your brand strategy, which is an important outcome for your company and team.

As you think about web site copy or the tone and style of your user conference, your positioning statement will clarify your team’s thinking and ensure alignment across different parts of the organization. Same ingredients, same recipe.

But as you go to market, your position will play an important customer-facing role as well, asit will also help your customers understand where you fit in their understanding of the world.

My favorite metaphor for the concept of positioning is to think of positioning as a map. One use for a map is to help you navigate from point A to point B, which is really important when you know exactly where you currently are and specifically where you want to go.

But what if you’re in an unfamiliar area and you’re not quite sure where you want to go? Explicit and linear directions don’t help so much in that case, which points to the second use for a map: a map orients its readers to their surroundings.

I recently planned a trip to Paris, and long before I set foot on its cobblestones, I spent plenty of time with Google Maps understanding the relationships between key landmarks, where the Metro runs, and which neighborhoods have the best places to eat (hint: it turns out it’s all of them).

Once we made it to Paris, we used the map to discover things we didn’t previously know about, from highly rated boulangeries to small but grandiose medieval churches.

The map was less about tactical navigation and more about familiarity and context. It was about understanding where we lived for a couple of weeks.

Now, in some well-known categories, it’s possible that customers already know where they are and where they want to go and, as a result, don’t rely on maps for orientation. Consumer packaged goods (CPG) products are a typical example of a familiar territory. My bet is that when you run out of toothpaste, you either buy exactly the same brand you’ve used your entire life or you grab whatever is on sale. It’s a simple and low-stakes decision.

I’d also bet that the market your company competes in is newer or more complex than toothpaste. Your buyers may not understand what problem you’re solving or even know that such a solution exists and, as a result, don’t know how your product should fit into their toolbox. But positioning can help.

For a startup, your positioning orients your audience to the territory you inhabit and tells them specifically how they should think about your brand.

This is important: if you don’t tell them, they’ll make it up themselves, or worse, your competition will do it for you. Neither of those outcomes is ideal.

In its early days, customer success software maker Gainsight faced exactly this challenge in its effort to provide customer success teams with powerful tools. But at that time, “customer success” was an entirely new concept. Buyers didn’t necessarily understand their problem, and they certainly didn’t know that something called customer success was the solution.

The market didn’t know where Gainsight fit on the map and, as a result, tried to apply imprecise mental models to the company. Gainsight’s former CMO, Anthony Kennada, describes early conversations with analysts from Gartner and Forrester:

So, they said, “You guys are like proactive customer support,” or “proactive account management.” So, if we didn’t create a category, Gainsight would be the proactive account management company, and I think we’d be in a lot different of a place.1

Over the past several years, the leadership at Gainsight has positioned the firm as the leader in the customer success category—a category they created through deliberate choices based on their brand strategy.

They were deliberate about this positioning and resisted the market’s attempts to describe them in existing terms. They provided a clear map and have built a unicorn as a result.

So is category creation the only reason to invest in positioning? Why do you need to provide a map in the first place? Can’t people just connect the dots and figure it all out on their own?

Well, maybe, but “figuring it out” is the wrong framing for this discussion. In reality, your potential customers busy, and they’re not going to take the time to figure you out. It’s too much work.

Our goal, then, is to provide a clear way for our audience to understand and remember our brand. A good map orients its reader to their surroundings, and over time, the landscape becomes familiar and navigable. We know our favorite route home and where to find our favorite coffee spots. The patterns emerge from the previously unfamiliar terrain.

As it turns out, patterns play an important role in brand building. Cognitive psychologists have shown us that brains are pattern-matching machines and that potentially all brain function is based on the brain’s pattern recognition capabilities.2

One outcome of this pattern matching is that we’re constantly looking for ways new things relate to concepts we already understand.

Have you ever told a friend about a new book you’ve just finished reading, and they say something like, “Oh cool that sounds like Harry Potter but with vampires.” This happens with new company ideas too: “It’s like Uber but for landscapers.”

People automatically and subconsciously make these “X-for-Y” analogies whenever they encounter a new object or idea. Your positioning efforts will help ensure those variables are filled with the most powerful and relevant associations, rather than leaving it all to chance and hoping for the best.

Another outcome of our brain’s natural pattern-matching tendency is that we have trouble making memories from thoughts and ideas we don’t already have a mental map for. If we don’t understand the context, it’s harder to store in memory.

It turns out some memories are created from various senses, like sight or sound. But there’s another type of memory called semantic encoding

that deals with meaning and context, and it is believed that this is the way long-term memories are stored.3

Positioning will help your audience understand and remember your offering by providing a clear map to decode and store your context.

To understand how positioning addresses with this realty, let’s look to the classic book on the subject, simply called Positioning, by Jack Trout and Al Ries. Anyone discussing positioning should start there, and I highly recommend reading the book.

A central premise for positioning, in both Positioining and in the practice in general, is this:

The mind, as a defense against the volume of today’s communications, screens and rejects much of the information offered it. In general, the mind accepts only that which matches prior knowledge or experience.4

People are simply overloaded by communications of all types, and as a survival method, people’s brains tune out most new information, processing and accepting information that’s consistent with their existing view of the world.

Given this information overload, how can a brand communicate its value to a market in need? According to Ries and Trout, “You look for the solution to your problem not inside the product, not even inside your own mind. You look for the solution to your problem inside the prospect’s mind.”

In other words, you draw a map that illustrates where your offering fits within the territory they’re already familiar with. The work on the canvas so far should provide solid context for this exercise. You’ve dug into your audience, you know how they perceive the market, and you know what the competition is up to. These perceptions are central to this step of strategy development.

That’s because, “the essence of positioning thinking is to accept the perceptions as reality and then restructure those perceptions to create the position you desire.”5

Your map, then, won’t draw a foreign and unknown landscape. I love the maps drawn in The Lord of the Rings and other fantasy books, but they’re not very useful for navigating and understanding the world I actually inhabit.

Instead, your positioning statement will build from the insights you’ve already gathered in your research so far. The task now is to survey that landscape to craft and idea that will connect to what your audience already believes about the world.

To get started, we’ll look at the parts of the positioning statement, then unpack an example and discuss how it all fits together.

First, Table 5-1 shows the parts of the positioning statement.

Table 5-1

Parts of the positioning statement

Audience | Who are they, and what is their most important psychographic need or desire as it relates to the brand’s category? Focus on describing a single persona. In other words, don’t cram two or more unique audiences into this section; it’s all about choice |

Brand description | What is the simplest description of the product? Or what is the broader, more strategic frame of reference? |

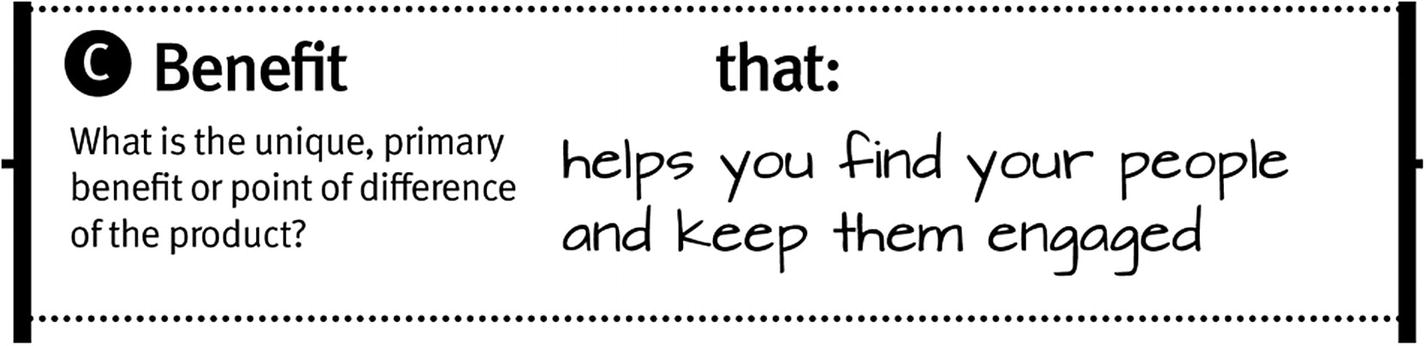

Benefit | What is the unique, primary benefit or point of difference of the product? |

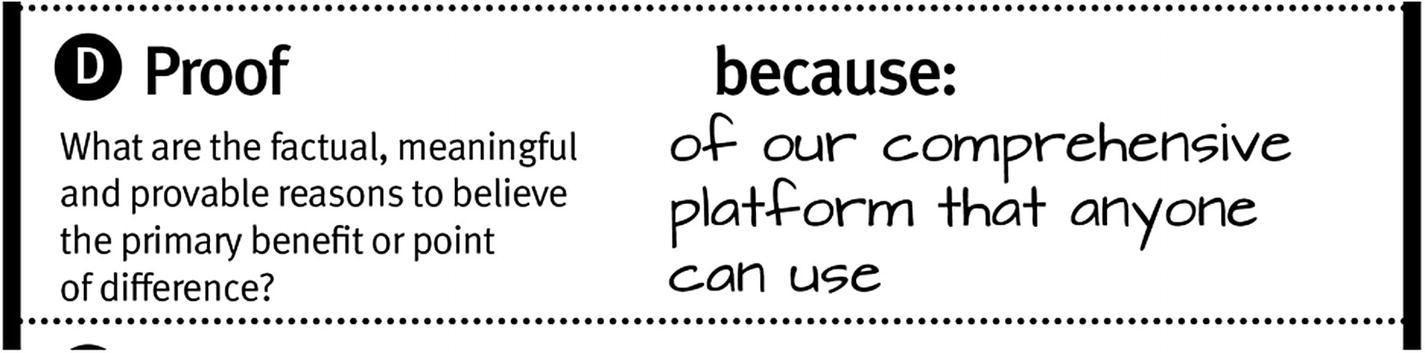

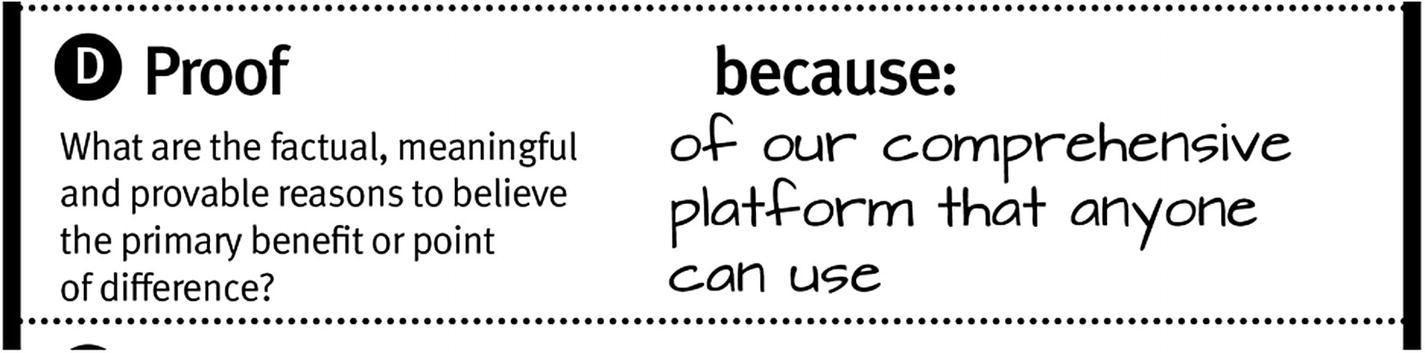

Proof | What are the factual, meaningful, and provable reasons to believe the primary benefit or point of difference? |

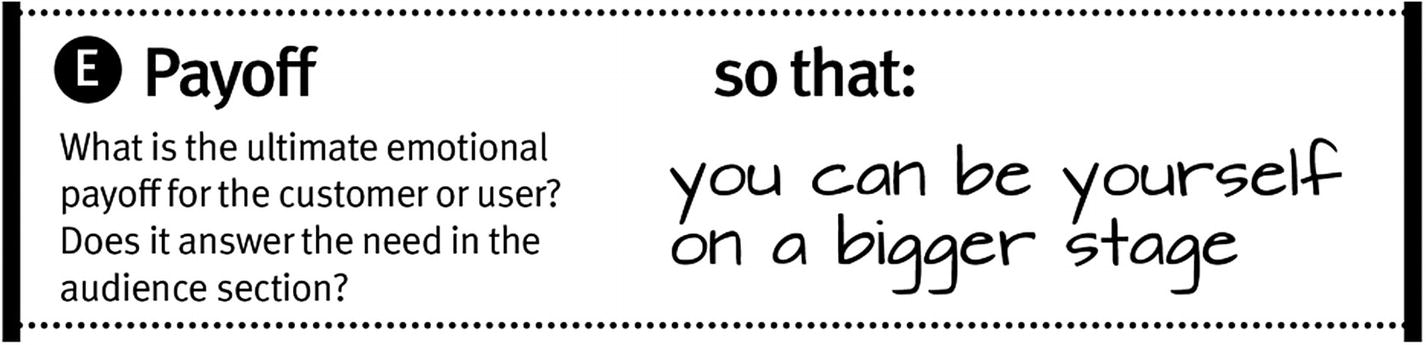

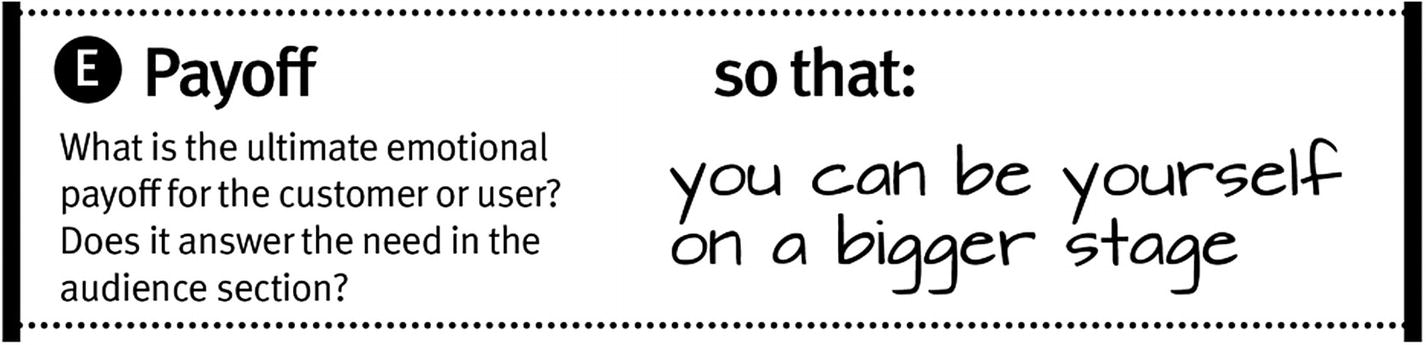

Payoff | What is the ultimate emotional payoff for the customer or user? Does it answer the need in the audience description? |

Brand essence | What is the core idea or defining concept of the brand? Is it tangible or attitudinal? (Unique, succinct, pithy, and ideally 2–4 words) |

When complete, the statement reads like a sentence:

For [audience], brand is [description] that [benefit] because [proof] so that [payoff].

Let’s jump right into the example to see how this plays out.

Example Positioning Statement

For growing businesses with strong opinions, MailChimp is the creative marketing platform that helps you find your people and keep them engaged because of our comprehensive platform that anyone can use, so that you can be yourself on a bigger stage.

Brand essence: Keep growing.

Okay, so we’ve said a lot about Mailchimp so far, whittling down all the potential directions into a few key insights for each box. Based on what you know about them, you can see how there are tons of potential directions for each phrase in the statement. You’ll also see that what you choose for each part of the statement will influence the direction of your strategy overall.

Each decision impacts all others in a complex web, so give yourself some time to explore this section, and try different pieces until the puzzle fits.

To help you get there, let’s dig into each line of the example positioning statement and explore how alternative choices would influence the strategy.

Audience

For starters, “growing businesses with strong opinions” (Figure 5-2) represents a specific choice that highlights the attitude of the audience in a manner that’s more psychographic than demographic.

Figure 5-2

The audience description

Though Mailchimp talks a lot about creative businesses, the truth is, if you view yourself as a growing business and have strong belief about the world, Mailchimp is here for you. Plumber, CPA, glass blower—it doesn’t matter.

How different would the positioning statement look if it were “For small businesses and nonprofits on a budget” or “for medium-sized businesses with 250 or more employees”?

That single shift in the language would massively transform the strategic direction. The company might have similar underlying features, but you can see how the brand would live on a completely different planet from Mailchimp.

Quick Exercise

One mini-exercise to try in this part of the positioning statement comes from Ries and Trout: “Rather than asking yourself, ‘Who are we trying to appeal to?’ try asking yourself the opposite question, ‘Who should not use our brand?’” I call this your anti-audience.

After testing a few iterations of your Audience box, grab a few index cards and try to characterize your anti-audience. For example, a premium coffee roaster might describe its anti-audience as “People who drink coffee only once or twice per month.”

This simple little move will help clarify your thinking and draw clear lines around who’s in and who’s out of your target audience.

The goal of this exercise is to explore and discuss all the edges of your Audience and not to perfectly articulate the anti-audience description, so have fun and push the boundaries a bit.

Brand Description

Next, let’s dig into the brand description (Figure 5-3). In the example Description part of the positioning statement, we’ve described Mailchimp as a “the creative marketing platform.” Not just an email or newsletter tool, but a platform that’s innately creative. This strategic framing will enable more compelling execution later vs. a straightforward descriptor like “newsletter tool.”

Figure 5-3

The Product Description

The choice of “creative” works on two levels. First, it speaks to the kind marketing implemented by its users and is a bit of a wink to insiders. “Yeah, we’re creative, not like those small businesses that use Constant Contact.” It’s a nice signal to current and potential customers, as well as to employees of Mailchimp.

At a higher level, it speaks to the company itself and how it interacts with the world. Everything from the web site’s bright colors and quirky illustrations to the type of philanthropic support MailChimp provides reinforces to their audience that “We ourselves are creative, just like you!”

Again, how different would the strategy look if the description were something like “the most powerful email marketing software”? “Email marketing software” draws a hard line around how the company would perceive and talk about itself.

Would the brand really want to focus so specifically on email marketing? It would probably focus our key messages, but it would also limit the scope of our offering to email only.

Instead, “creative marketing platform” is specific enough to manage the scope of the positioning coupled with an emotional differentiator.

Of course, the risk for this part of the statement is to go the opposite direction of “email marketing software” and draw the circle too broadly. To illustrate with an extreme example, what if we’d written “the most powerful business software”? You can see how business software goes too up the ladder of abstraction and is too broad to be meaningful to the company or the audience.

So how should you decide between a straightforward description and a more strategic framing? One rule of thumb is to consider the maturity of your category. In other words, are there lots of incumbents, or are you creating a new category?

If you’re entering a crowded space, like online marketing tools, a creative and strategic framing might help drive clear differentiation.

On the other hand, if you’re the first mover in a new market, a more direct approach might help you clearly plant a flag in the mind of your audience. In their early days, Gainsight worked hard to position themselves as the leading customer success software vendor while also creating the category of “customer success.” For that reason, they probably would have chosen a very direct description for their Brand Strategy Canvas, since something broader or more abstract would further cloud the waters of the new market.

Benefit

There are lots of key benefits, but we’ve chosen to point out that Mailchimp “helps you find your people and keep them engaged” (Figure 5-4). This dual benefit speaks to the comprehensive nature of the platform.

Figure 5-4

Description of the primary benefit

It’s not just for blasting emails. Rather, given the list of features, including integrations with advertising platforms and mass mailers, it allows the user to locate their audiences to start a conversation.

For new and existing customers, the platform enables ongoing communication and engagement. And we know these two benefits—both finding new customers and engaging existing ones—are important to growing businesses.

There are many other potential directions for the benefit, given the set of features offered by Mailchimp. We could’ve emphasized the depth and power of the platform’s many features, saying something like, “… that equip teams with customizable tools.”

A key benefit like that might speak to an audience of seasoned marketers with experience on other complex marketing platforms, and an overall strategy along those lines would focus more on the power that comes from mastering all the complex features, rather than simplicity and ease of use.

Proof

What’s the reason to believe the claim that Mailchimp helps growing businesses find and engage with their audience? It’s “because of our comprehensive platform that anyone can use” (Figure 5-5). We know that the tool is built in such a way small business owners can implement even the most complex features themselves, no prior marketing experience required.

Figure 5-5

Description of the main proof point

But that’s only true because of the company’s investments in intuitive user interfaces, clear design, and thorough help documentation. There are specific product choices we can point to support that claim that the platform is comprehensive and easy to use.

What might alternative approaches to this box look like? This box obviously depends heavily on the prior boxes, so for the sake of illustration, let’s say that the prior boxes have emphasized high-end white glove service.

In that case, the Proof box might point out that Mailchimp has invested heavily in building out its partner network and its 24/7 support offering. Those investments would be used as proof points to support claims about, for example, peace of mind for the users, since there’s always an expert available to help.

Payoff

Now let’s look at that the payoff of the statement, which reads “so that you can be yourself on a bigger stage” (Figure 5-6). The payoff should look back at the audience description and articulate their desires in a succinct and powerful way.

Figure 5-6

Description of the payoff

We know our audience see themselves as growing companies, with big opinions, and big dreams as well. Mailchimp understands these folks and will help them evolve to bigger and bigger stages.

This aspirational idea pays off what we know about the Audience, namely, that they are “growing businesses with strong opinions.” Powerful positioning statements will always possess the kind of logical consistency that comes when Audience and Payoff are closely related.

Once you’ve completed your positioning statement, one quick way to test its internal consistency is to ask yourself a question like, “Would [audience] care about [payoff]?”

In this case, would a growing business owner with strong opinions care about being herself on a bigger stage? Yep, that makes sense. On the other hand, if the Audience were “small businesses on a budget,” this payoff wouldn’t resonate, and we should probably reassess part or all of the statement.

To unpack an alternative example of a Proof, what if the rest of the positioning statement was all about concierge service, as we explored in a prior section? If the benefit focused on expert and available care, with proof points about 24/7 service and a robust partner network, what might the payoff look like?

Assuming our customers were busy business owners with many priorities, the payoff might be something like “So that you can focus on running your business.” In other words, don’t worry about online marketing; you have more important priorities.

Of course, with our current example, a payoff emphasizing the audience’s other priorities wouldn’t make any sense. That’s because we’ve made deliberate choices in prior boxes of our positioning statement that, to some extent, make the payoff of “you can be yourself on a bigger stage” feel somewhat unsurprising.

And that’s a good thing! Aristotle, who wrote extensively about the structure of powerful stories, said story endings should be both unexpected and inevitable. Throughout, the story should provide readers with a clear sense of the what’s coming but deliver the ending in a way they couldn’t have predicted.

In a crime thriller, you know before sitting down in the theater that the cops will catch the killer. But you don’t know how, and you’ll pay good money to find out.

In a similar way, your positioning statement should lay the inevitable groundwork for the payoff, with the payoff itself delivering a bit of surprise. “Be yourself on a bigger stage” makes perfect sense for this positioning statement, but it’s also creative, surprising, and inspirational.

A big part of its energy lies in its emotional nature. The ideal payoff will resonate on a higher emotional level and should build on and transcend the rational benefits already stated. An emotional payoff will inspire and animate your brand in ways that features and rational benefits cannot, and will provide a foothold for differentiation from others in your market. As a result, give this box extra attention as you complete your positioning statement.

Brand Essence

Finally, we come to the Brand Essence. This piece of the positioning statement attempts to distill the defining aspects of your brand into a short statement (Figure 5-7).

Figure 5-7

Articulation of the brand essence

The example Mailchimp strategy covers a lot of ground, including creativity, good taste, design and experience, and a helpful tone, so it’s tough to pick just one big idea in 2–3 words.

But for growing business, Mailchimp’s efforts all revolve a central idea: keep growing. This idea permeates their choices as the ultimate why at the top of the ladder of abstraction.

Of course, the reasons individual companies or people will want to grow will differ greatly, but the spirit of growth unites them all, and unites the Mailchimp brand strategy.

Because the brand essence is such a powerful part of the strategy process, let’s explore a few more aspects of understanding its importance and developing on of your own.

Two Reasons to Develop Your Brand Essence

It’s probably clear by now that the trickiest part of your positioning statement is the brand essence. The essence tries to distill your entire canvas into 2–4 words. It’s tough, but is it worth the effort? I think so, for two reasons.

First, editing your thinking this way will challenge you to consider every decision you’ve made so far. In the process, you’ll challenge your assumptions, often viewing prior choices in a fresh light, and possibly uncover new approaches to reintegrate into prior sections.

In this way, the brand essence serves as kind of a checksum. As technical readers will know, a checksum is a number that allows end users to ensure the veracity of transmitted data. It’s basically way for you to assess the contents of the positioning statement and answer the question, “Does this all check out?”

In the same way, the brand essence ensures the choices in your positioning statement tell a consistent and coherent story.

Practically, if you find yourself struggling with the brand essence, consider reviewing the parts of your positioning statement and making sure they build on each other.

Second, the essence often inspires interesting ideas for execution

, leading to creative language or taglines that capture the spirit and culture of your company. Constraints breed creativity, and the 2–4-word limit is the ultimate constraint.

In my experience, an effective brand essence will fall into one of two types: rallying cry or promise.

Brand Essence As Rallying Cry

One startup accelerator I worked with had built a reputation for working tirelessly on behalf of their portfolio companies. After lots of thinking, we landed on the brand essence Never Stop.

Their strategy was complex, taking into account a half dozen audiences of stakeholders. And yet, the simple notion of Never Stop has become their motto, allowing them to quickly communicate and remind their team about what makes the different from slower-moving organizations competing for similar resources.

Brand Essence As Promise to Uphold

Second, a brand essence can often function as a promise to uphold

. I once helped rebrand a century-old logistics company that’s facing increasing global competition and seeking to reposition itself as an expert boutique firm enabled by smart thinking and creative use of technology.

After spending several weeks diving deep with their team and interviewing their customers, we distilled their brand strategy into a two-word essence: Uncontained Tenacity.

As a shipping company, the “uncontained” was a nod to the shipping containers so prevalent in modern logistics, while “tenacity” spoke to the cultural differentiator that team members and customers alike used to describe the company’s approach.

Like Never Stop, this essence is aspirational—most great ones are—but it functions more like a promise, between the team and their customers, and among themselves. It’s a reminder and encouragement about how the brand behaves that will inform external and internal communication alike.

As you can see, the work to distill your strategy into at 2–4-word statement will take and intellectual rigor, but the resulting clarity and alignment will instill confidence in both your team and your audience.

Generating a Brand Essence

So how do you land on a powerful brand essence? While there are no simple hacks, here’s the good news: because you’ve spent so much time consideration your strategy, my guess is you won’t be far off from an essence by the time you need to articulate it.

My primary advice here is to commit to generating at least 10 different options. You’ll want to stop on the first one and you’ll probably be begging to stop after three or four. Your brain will promise you it’s perfect, but don’t listen. It’s just trying to trick you out of the additional hard work.

By committing to at least 10, you’re setting the expectation for yourself and your team that you’re going to push past the obvious and explore the truly novel. Of course, you may find that your first attempt actually was the best, and that’s okay. But at least by then you’ll have given yourself the permission to explore.

Reviewing Your Positioning Statement

As you can see, the choices made here will impact future decisions about your brand.

The most important thing to remember about the positioning statement, and brand strategy overall, is that decisions matter.

Given the stakes, I recommend iterating over several versions of your statement. Don’t overthink the first few; just get something on paper. Then mix and match different choices and see how they fit together.

Once you complete a version of the statement, use the five criteria in Table 5-2 to assess your statement. Ask yourself, “Is this positing statement…?”

Table 5-2

Criteria for assessing your positioning statement

Important | Will this positioning resonate with the audience? Does it provide a clear “So what?” for their most pressing needs? |

Unique | Are you the only company who can make these claims? Is the statement based on differentiated features or ideas? |

Believable | Does this statement ring true? Can you back it up with concrete evidence? |

Actionable | Does the statement provide you with a clear path to execution? Does it lead naturally to ideas for a brand name, web site design, campaign concepts, and other kinds of execution? |

Sustainable | Is the idea big enough to last multiple years, or does it rely on a trend or a fad in the market or in culture? |

Tips For Expoloring Your Statement

I often create a Kanban-style board to explore how different phrasing fits together, allowing me to mix and match different combinations. Many won’t really make sense, since many times the parts of the statement are interdependent.

But that’s totally okay—we’re just exploring at this stage. And many times, the free-form exploration will uncover a combination I hadn’t previously considered, opening up an entirely new direction to consider.

Of course, if your style is more hands on, the same approach works with index cards and markers.

Drawing the Right Map

The positioning statement is powerful because it helps clarify and distill all of your potential directions. But there’s another reason you’ll want to spend plenty of time on this section. As we discussed earlier, it also provides a frame of reference for talking about your offering in the context of the market. The map of your territory.

In other words, a strong position will help people know how your brand fits into the world as your audience knows it.

But drawing a map with the wrong frame of reference can limit your brand’s potential, or worse, confuse your audience.

For example, in my hometown of Memphis, there’s a wonderful AAA baseball team called the Redbirds. The stadium is legitimately the best in the minors, and it’s the only ballpark in America where hotdogs are not the best-selling food item (it’s actually BBQ nachos, which is amazing as it sounds).

Let’s say the Redbirds were working on their positioning statement, and they described themselves as “the top AAA baseball team in Memphis.” That claim might be true, but it wouldn’t be useful, mainly because they’re the only pro baseball team in the market. They’re the best by default.

So in this case, a straightforward positioning is irrelevant and provides no opportunity for further brand development. So how should they position themselves for maximum impact?

For one, drawing a broader map would help, one that takes into account what they’ve learned about their audience and the competition and the market. In the case of the Redbirds, their competition is not other baseball teams but rather alternative entertainment venues.

The competition is indirect, since the Redbirds are competing for budget and not against a parity offering.

So, a more strategic brand description might look something like “The Memphis Redbirds is the entertainment experience for active families….”

In this way, we’ve reframed the Redbirds as a purveyor of family-friendly entertainment for busy families who would enjoy the chance to enjoy the outdoors for a few hours, take in a game, have some BBQ nachos, and laugh at the antics between innings.

This framing provides a much richer point of departure for the brand vs. one that describes the brand simply as a AAA baseball team. It’s a wholesome and engaging way to spend the afternoon with the family, and it just happens to be baseball.

This approach takes into account the desires of their audience as well as the indirect competition from other family fun options, like the zoo or the movies.

With this kind of description, it becomes clear how the strategy will be developed in the context of all the options a family has at its disposal. Understanding your framing will also allow you to think in terms of share of wallet.

Share of Wallet

When thinking through your positioning and considering various choices, another helpful lens for exploration is to think of how your audience views your offering in the context of how they allocate their budget.

In our baseball example, the Redbirds aren’t competing against other baseball teams but other family entertainment options, like the Memphis Zoo, the Children’s Museum, and other compelling opportunities.

One big question, then, is how we can grab more share of wallet from those in our target audience. If given the choice between, say, the zoo and a day at the ballpark, how can our brand strategy work to increase the likelihood of our audience choosing the latter?

There are lots of answers to that question, but at least one approach is to consider how your self-definition influences your positioning statement, which drives the direction of the entire brand strategy.

In other words, the framing of the Redbirds as a family-focused entertainment experience, rather than a baseball team, provides the platform for competing with the budgetary alternatives.

Often, SaaS startups define themselves in a way that emphasizes the features or functional benefits—the best tool for surveys online, the fastest way to deploy containers, the top baseball team.

As you explore your positioning statement, then, keep in mind how your self-definition will enable you to address the various types of competition.

Conclusion

The positioning statement is the most important part of your brand strategy, so congratulations for making it this far! By this point, you should have several versions of potential statements, as well as a framework for assessing each option.

In the coming chapters, we’ll begin exploring ways to bring your strategy to life through execution, but the effectiveness of your execution will depend heavily on the quality of your positioning statement.

I know it feels like a lot of work, but be sure to give yourself and your team plenty of time to ideate and explore. The thinking and effort you invest here will pay off many times over

Footnotes