Chapter 4

Mapping the Community Participation Journey

Now that you have the first stage in the Social Identity Cycle under your belt, we're ready to move into the second stage, participation.

The participation stage is all about understanding the journey that a member goes through in your community over time, and facilitating spaces and experiences that move them along that journey. Early in the journey, it's likely that members will participate in smaller and more passive ways. Over time, as they move through the cycle, they'll become more committed and participate in greater ways, taking on larger roles in the community. In this chapter, you'll learn how to design your community member journey and give your members a range of opportunities to contribute.

We'll talk about how to attract and onboard new members, how to create a “power user” status, and what you need to do to activate community leaders who will contribute to facilitating engagement in your community.

The Commitment Curve

When we think about community participation, we tend to just think about the big actions we want community members to take, like posting in a forum, attending an event, organizing events, and becoming power users or leaders.

In truth, there are going to be a whole lot of actions, small and large, that someone can take along their journey of becoming an engaged member of your community. Participation can be as simple as reading a blog post or subscribing to a newsletter to start. Then as someone moves through the Social Identity Cycle over and over again, and they become more invested in the community, they will be more likely to participate in greater ways.

It's your job as the community builder to facilitate that experience for your members. You want to understand all the different ways that someone can participate in your community and, using the cycle, move them along that journey.

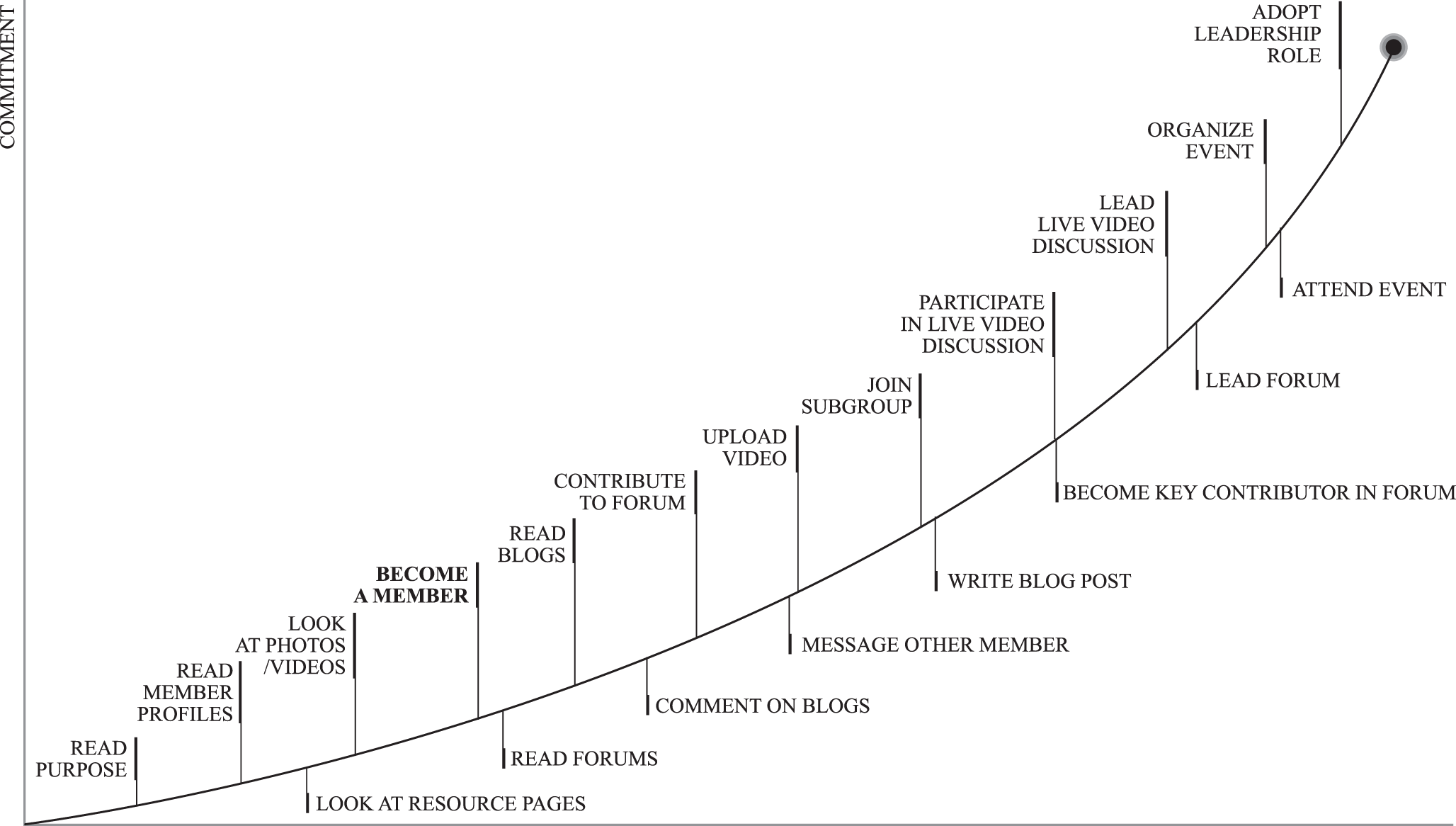

A useful tool for mapping out this journey is called the commitment curve. The concept of a commitment curve was first developed by Darrel Conner and Robert Pattison in 1982 as a tool to explain how an individual adopts organizational change over time.1 The commitment curve was later adapted to communities for the purpose of understanding how an individual becomes more committed and takes greater actions within a community over time.

I first learned about the commitment curve from Douglas Atkin when he was the chief community officer for Meetup back in 2008. The goal at Meetup was clear: get more people to host meetups. Millions of people had signed up for Meetup, but if there weren't events for them to go to, they wouldn't stay engaged and the platform would plateau.

When Atkin dug into the experience that members were having and researched why they weren't starting their own events, the answer became clear. Meetup was asking its members to host events, which is a huge commitment to the community, right when they signed up. They weren't committed enough to participate in that big way, and so they would just drop off and not participate at all.

“Welcome to our community; please make a massive commitment of time and energy!” isn't a very logical way to motivate people to do something, but that's exactly how a lot of communities and community products are designed. We, as the organizers, know what we want our members to do, but we're impatient and want them to jump right to the high-commitment contributions. For the majority of our members, it will take time for them to get to the point where they're committed enough to participate at that level. You need to make smaller asks first.

This is where the commitment curve comes in. The idea is that over time, your members' level of commitment will increase. As their commitment to the community increases, their willingness to make larger and larger contributions to the community goes up. So you need to only make smaller asks of members at the beginning of the curve, and increase the ask as they move up the curve.

Figure 4.1 shows what Atkin's commitment curve looked like at Meetup.

Instead of welcoming members to the community and immediately asking them to host a meetup, they started easing members into the community with smaller asks. Fill out your profile. Add a picture. Read a blog. Subscribe. And when you're ready, maybe attend a Meetup so you can get a feel for the community.

Now, all members aren't going to follow the commitment curve exactly the way you draw it up. Some members will join and find the community to be such a good fit that they're ready to take action and make larger contributions right away. Some members might spend years in your community and never quite get to the point where they feel motivated to increase their commitment. And some members will move up the curve, and back down the curve as their life and needs change, or the community changes.

By mapping out your community commitment curve, you can lay out all the different actions you want your community members to take, and make sure you're asking for bigger commitments only when members are ready to make that commitment.

The Four Levels of Participation

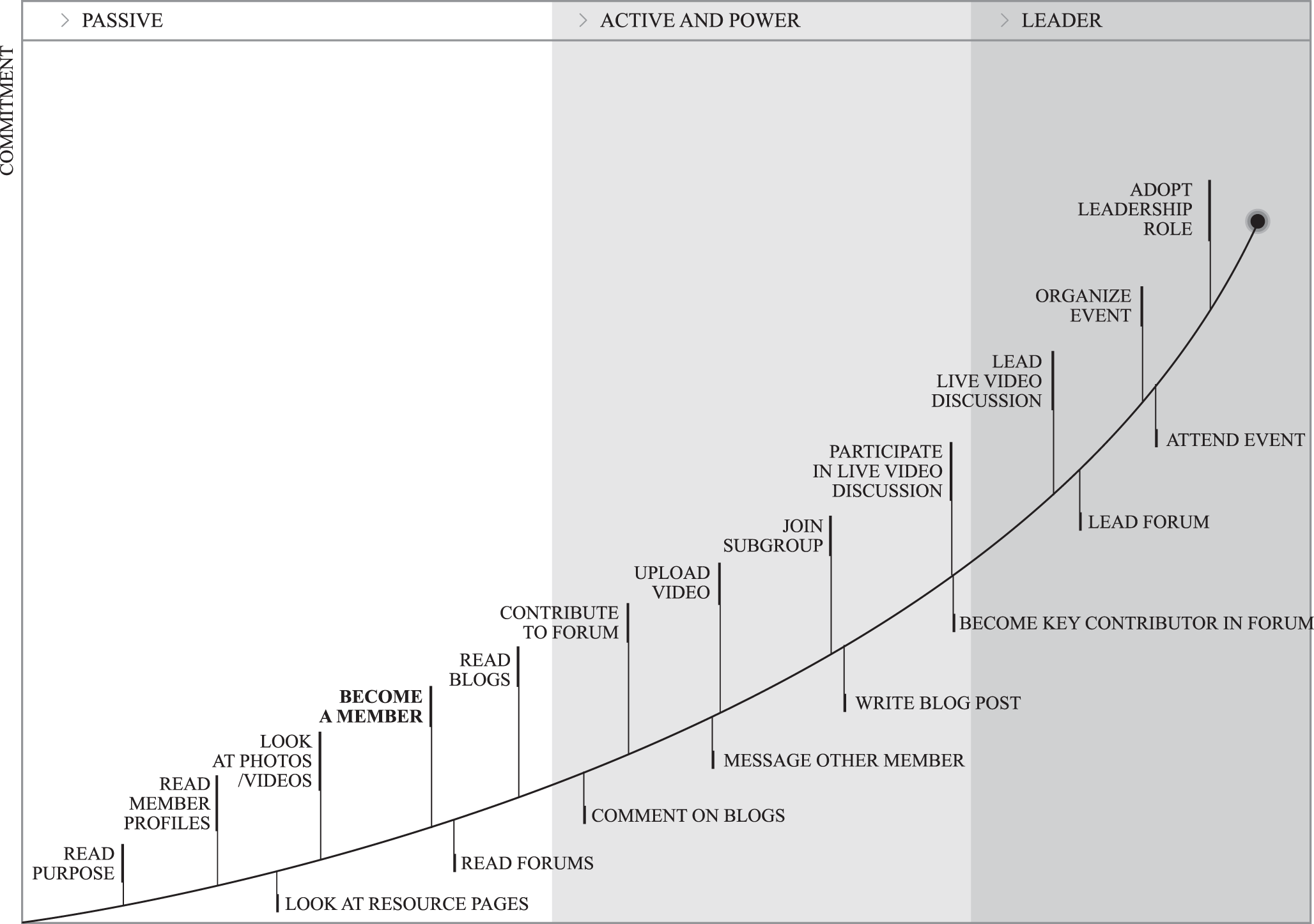

Remember that once your community reaches the late growth and maturity stages of the community lifecycle, you'll find that a natural striation of participation levels start to form. In Chapter 3, we talked about how communities will form different buckets of participation as passive members, active members, power members, and leaders.

We can map these levels to the commitment curve to better understand the phases that a member goes through as they become a more committed member of your community. Figure 4.2 shows how you could break down Atkin's Meetup Commitment Curve, for example.

Passive members are folks who are at the start of the commitment curve. They're participating in smaller, lower-commitment ways, mostly consuming content, learning, and listening. A passive member is what we often call an audience member, or lurker. They don't contribute by creating any content or engaging in any discussion, they just want to listen for now.

An active member is someone who participates by joining in the discussion and creating content. They're a bit further up the commitment curve. In digital spaces, they're creating new discussions or responding to existing discussions. In physical spaces they're meeting people, joining in discussions, and sharing their learnings.

A power member is someone who is so committed to the community, so engaged, that they contribute at very high rates. They're the first one to jump on a lot of new threads in your forum. They show up to every event. They use your product religiously. Like we discussed in Chapter 4, sometimes companies create a distinct identity just for their power users.

And finally you'll have the leaders. These are the folks who take on roles like moderating a digital space, becoming an admin of a subgroup, or launching a local community chapter. They create and facilitate spaces and experiences for other members.

Now it's common logic to say, “Great! Now in order to build an engaged community we just need to motivate all of our passive members to be active or power members!” But the truth is that ALL of these roles are critical to communities. Passive members play an important role. They provide the eyes and ears that the active and power members care about. Without the passive members there to consume, the active and power members have less of an audience to consume their content.

You'll ultimately need all four levels for a large, mature community to work: leaders, a core group of power members, a consistent group of active members, and an often-larger group of passive members.

An engaged community is an ecosystem made up of people moving up and down the commitment curve over time.

And every individual member's journey will be different. Members can, and often will, skip around up and down the curve. They might jump ahead to be an active member right away. I've seen people join the CMX community and feel so inspired that they immediately apply to start a local chapter. Members can also fall back down the curve if they fall out of the Social Identity Cycle and no longer identify with the group, no longer feel motivated to participate, or no longer feel validated for their participation.

So the idea that all members need a lot of time to become a committed member of your community isn't always true. Sometimes when they're the right fit, they can go from zero to 60 real fast.

Generally, you want to focus your engagement strategy on the inner circles. The Pareto principle applies here, which predicts that roughly 80 percent of the content in your community will be created by 20 percent of your members. While this principle doesn't apply to all communities, it's a common distribution found in large social platforms. So you want to make sure that 20 percent is set up to be really happy, engaged, and successful. You'll grow your community a lot faster by working to get that 20 percent to double their commitment than by trying to get the other 80 percent of your community to increase their commitment by fivefold.

But remember that all the layers are important. YouTube has many, many layers of identities in their ecosystem. Of course, it's the creators on YouTube, the people posting videos consistently, that create the value on the platform. But without the 99.9 percent of users who just watch videos there to consume, those creators don't have a reason to create, so it's all needed to make the ecosystem work. YouTube spends a lot of energy building tools to make it easier for users to consume content and subscribe to creators. Lyft drivers won't participate if there aren't people to book rides. eBay sellers won't post their items for sale if there isn't anyone there to buy. The creators need the consumers.

Prioritize keeping your inner rings engaged and successful. But don't forget about the outer rings and the value of your audience. Make it easy for your passive consumers to passively consume. Get them the content they need in the most efficient way possible. Love your lurkers.

How to Attract Members to Your Community

If you look at any complete commitment curve, you'll find that the member journey starts before they officially become a member. They'll have to hear about your community first, do their research, and make a decision to join.

How people find your community will depend on the stage of your community, the kind of community you're building, and how established your existing audience is.

If your community is still in the seed stage, I recommend starting with a minimum viable community (MVC). The idea is that you don't need a big, automated community program to validate that people actually need your community and are interested in the social identity you're gathering. You can build a very simple, manually powered version of your community and start getting member feedback much more quickly.

You should plan on no organic growth in the early days.

There's this rosy picture that people like to paint when talking about community building. A person has an idea for a community, hosts their first event, and it catches like wildfire! It grows and grows until wow, it's a global community!

This narrative is misleading. It makes us think that if we can just set up the right circumstances – the right message, in the right space, with the right programming – then people will flock to our communities. It's that “if you build it they will come” energy.

They won't come. If a community grows organically from day one, it is the extreme exception to the rule. In reality, every community builder I've ever spoken to talks about how hard they had to work to get their first members in the door. Most communities start small and stay small, never expanding beyond the first group of founding members. The ones that get big are a direct result of leaders working to recruit new members, spread awareness, and essentially market their community like you would any other product or service.

Of course, organic growth sounds a lot better from a marketing perspective. There's a temptation to make it look like we didn't have to work very hard for our community growth. We want it to look like our community was so awesome, it just grew on its own. A lot of businesses brag about spending $0 on marketing for the same reason. Behind the scenes, you'll find a team hustling, sending emails, hosting events, promoting content, and doing everything they can to fill their funnel.

Hope for organic growth, but plan for manual growth. Get ready to roll up your sleeves and make it grow. Any organic, “word-of-mouth” growth that you get on top is gravy. Just don't rely on it.

When we first decided to host CMX Summit, before we even had a website, I sent around 300 personal emails to people asking them if they'd be interested in a conference for community professionals. If they said yes, I'd personally follow up with the ticket page once it was up and say, “Great! Here you go. See you there!”

When Ryan Hoover built the Product Hunt community, the first members were sourced from a series of brunch events he was hosting for entrepreneurs and product lovers. I was one of them! After months of hosting events, he emailed all of us and asked what we thought of a new idea he had where people could share cool products they discovered. Product Hunt was born! The first iteration was a group of less than 100 of us just sending Ryan our favorite products over email, and he would put them into a newsletter that people could subscribe to. It was a huge hit, and it start growing quickly. But it was only because Ryan took the time to build the foundation of community with a small group first. That group created the foundation of community, and a center of gravity that others were drawn to.

Both CMX and Product Hunt were very hands-on and personal in the early days. Look at any large community today and it's almost guaranteed that the founders were personally inviting members in the early days. Sarah Leary, cofounder and former CEO of NextDoor, talks about how in the very early days, they were literally knocking on people's doors to invite them to join the platform and try to get a critical mass of members for that neighborhood.

It will be easier to get your community off the ground if you already have an established audience and a foundation of trust. For example, if you already have 1,000 customers who use and love your product, it'll be easier to launch a forum and motivate people to become members – though I'd still recommend starting small, and with personal outreach. Being hands-on will make those first members feel special, and make them value the community more than if they just receive an invitation in a mass email.

Once you have the foundation of community, and you start finding community-market fit, your community will move into the growth state of the lifecycle and people will start to come to your community more organically. Members will invite other members rather than you having to invite everyone yourself. You can facilitate this experience by giving your members a certain number of invites each. Product Hunt did this in its early days, giving each of the founding members three invites. Because the community was so high quality, and the invites were limited, members took them seriously and only invited members that they thought would be valuable additions to the community. In the late growth and maturity stages, word of mouth often becomes the biggest driver of growth. Most people find out about CMX today because they bring up a challenge they're thinking about related to community, and another member recommends they check out our community.

Once your community is growing or mature, it's okay to take more of an automated, or traditional marketing approach, to growing your community. You should make sure your community is listed clearly on your website. If it's a customer community, think about where your community can show up on different parts of your website where your customers are already spending time, like in dashboards or in help documents. At CMX, we're constantly publishing articles and research to grow our audience, and then inviting that audience to join our community spaces through our newsletter and links from our website.

The platform you choose to host your community on can also be a driver of community growth. If you host your community on Facebook, Slack, Reddit, LinkedIn, or any large social network, you can tap into their network effects and recommendation engines. A lot of people find CMX through our Facebook group, which gets recommended to users who are interested in learning about community, and shows up in people's social feeds when content from the community is shared.

That really is the primary value add that hosting your community on an existing social network brings. It makes it easier to attract and engage community members since they're already spending time there. But it comes at the cost of ownership of any member data that could help you improve your community experience and connect community engagement back to your business's systems of record. Growing a community on an owned platform is harder in the short run, but more sustainable in the long run. We'll talk more about selecting the right community platform in chapter 6.

Creating Intentional Barriers to Entry

It might seem counterintuitive, but making it a bit more difficult to join your community, or making it difficult to reach a certain status in your community, will tend to create a stronger sense of social identity and belonging for those members.

Effort justification is a concept in social psychology that stems from Leon Festinger's theory of cognitive dissonance.2 It describes a person's tendency to attribute a higher value to an outcome that they had to work harder to achieve.

We see effort justification play out in a lot of social groups from military training, to pledging a sorority or fraternity, to converting to a religion, to trying out for a sports team. Groups that require a great investment of time, energy, or work in order to gain membership can become very strong social identities and highly committed communities.

Please don't start hazing your customers. But you can think about the requirements that someone needs to meet in order to join your community, or reach a status within your community.

To become an Airbnb “Super Host,” there are a range of requirements that hosts must meet. They can't cancel bookings, they have to maintain a minimum rating, and they must reach a minimum number of bookings in order to qualify.

Yelp has a range of requirements as well around how many reviews a Yelp user must have in order to be invited into the Yelp Elite.

Our inclination is to make the process of joining our communities as easy as possible. But the easier it is to get into your community, the less value people may apply to membership.

Some communities take the simple step of adding an application to join the community. So you can't just sign up, you have to fill out a form and answer questions to essentially show that you are a good fit for the community. That simple process of having to apply can make people value membership more greatly, and feel confident that the group will be curated and safe since every member is vetted.

Other communities make their community open to anyone, but make it difficult to reach a specific status within the community. For example, anyone can join the CMX community, but you must apply and go through an interview to become a CMX Connect host and start hosting local events under the CMX brand.

The members of communities with higher requirements are very proud of their membership. When they meet another member, they feel an immediate connection to each other. It's because they all went through the same struggle to get there. They all had to earn it.

Designing a Compelling Onboarding Experience

Once you've recruited a member, you now get to onboard them.

Too many companies miss the opportunity to make their onboarding exceptional. They create a really bland welcome email for everyone who joins their community, that makes a bunch of asks of the person, and just hope that they'll become an engaged community member.

The first time someone joins your community is a critical opportunity for you to make a good first impression, have a successful first run through Social Identity Cycle, and make it more likely that the member will come back.

Our prehistoric brains are primed to make snap judgments about people and groups based on limited information. In the early days of humanity, being able to immediately determine if a person or group was trustworthy increased the likelihood that we would survive. We have the same brain today, and we make the same kinds of snap judgments that become very hard to change once someone has formed an opinion.

So you don't want to leave your first impression to chance. When designing an onboarding experience, I like to ask three questions:

- What do you want them to know?

- What do you want them to feel?

- What do you want them to do?

For example, we personally welcome and tag every new member who joins the CMX Facebook Group and want them to…

- Know our vision, values, and guidelines so that they get inspired about the larger reason we're all gathering, and understand a bit about the culture we're intentionally creating.

- Feel very welcome, like they just found a community that they know they can trust and that wants them to succeed. We want them to feel accepted, inspired, and energized.

- (Do) take the first step of introducing themselves and to start browsing the content in the community to get a good idea of what people talk about.

I'm confident that if they are the right fit for the community, and we can make them know, feel, and do those things, the odds of them becoming an engaged member of our community are very high.

Remember, when they first join, you don't want to make a big ask for them. It can be so small that it doesn't feel like much of an ask at all. And it should always be presented as something that will bring them value. When we ask new members to introduce themselves, we tell them that we'd love to learn more about what they're working on, and we ask them to share one challenge that they're working through currently so we can immediately start bringing them value. And we ask them to browse the content so they can start learning and getting a feel for the space.

Onboarding isn't just for new members! Every time a member levels up into a new group or identity, you have an opportunity to onboard them again. If someone reaches a Power User status like the Airbnb Super Host community, you can onboard them and think through what you want them to know, feel and do when they first get inducted.

Whenever a CMX community member gets approved as a CMX Connect Chapter Host, we onboard them into our host community, and provide them with lots of information, resources, and experiences to learn about the program and get them started on the right foot. They get access to our private channel just for hosts, we send them our playbook, and we give them a big shout-out in the community as a new host.

How to Move Members Up the Commitment Curve

Now that you've onboarded your new members, your next logical question is probably, “How do you get members to start participating and move farther up the commitment curve?” Good question! Thanks for asking.

My belief is that you generally can't *get* anyone to do anything that they aren't organically motivated to do. If they don't care about your community, or they don't get value from participating, you can't make them care.

But if they are motivated, there may be obstacles preventing them from moving up the curve. Maybe they feel ready to post in your Slack group, but they don't know what's considered acceptable yet. Or maybe they want to launch a local chapter, but they don't know what the time commitment would look like or how to go about getting set up as a leader, so they don't move up into the leadership level.

Take the time to talk to your members at each level of participation and learn more about their experience. Ask your passive members if they'd be interested in participating more actively, and why they haven't taken that leap yet. Ask your power members if they'd be interested in becoming a leader and why they haven't applied yet.

From those interviews, you'll start to identify the obstacles that you can help your members overcome with better education and communication. You can then build that education into your onboarding experience and your community resource documents.

You can also run campaigns with the specific intention of moving members into the next level of participation. My friend Suzi Nelson ran a highly successful campaign specifically focused on activating the lurkers in the community she managed for DigitalMarketer.com, called DM Engage. She called it the “Love Our Lurkers Week.”3 Every day for five days, she posted a new piece of content in the community focused on helping overcome obstacles that passive members have. The agenda looked like this:

- Day One: Posting Tips and Tricks

- Day Two: List of Legendary Posts

- Day Three: Meet Our Most Influential Members

- Day Four: Why Contribute to DM Engage

- Day Five: How Your Community Manager Can Help You

This campaign aimed to show passive members how to contribute in a quality way, what great contributions and members look like, the value they'd get by participating, and how they can find help if they need it.

The campaign was a wild success. Nelson was able to activate 44 percent of the lurkers in their community. Of the members who never participated in the community before, 11 percent made their first post, 17 percent made their first comment, and 16 percent initiated a reaction (“liked” a post).

You can take this same idea and apply it to any level of participation. If you want more members of the community to apply to be a local chapter leader, then you can run a campaign aimed at answering common questions about being a leader, spotlighting successful leaders, and communicating the value that leaders get out of their participation.

You never know who might be motivated to participate more in your community, and just needs a little push.

Toward the top of the commitment curve, a lot of companies will create an official program and a distinct identity just for their power users. For example, Airbnb created the Super Host program, Notion created the Notion Pros program, and eBay created the Power Sellers program.

By creating a unique identity for your power users, you give them a stronger sense of community, and you give members in the outer rings something to strive for (to become a member of the power user group).

You may not know what qualifies as a “power user” right away. Over time, as your program matures, the requirements will get more defined and you'll be able to better articulate it to your community.

Power User status creates a clear goal for members to strive for. Members of power user programs typically get access to a range of perks and benefits, like exclusive events, access to more features, swag, and a direct line of communication with the company. We'll talk much more about how to reward your members, and power users in the next Chapter.

Activating Successful Community Leaders

At the very top of the commitment curve of any great community, above even power user status, you're likely to find official leadership positions.

Taking on a leadership role is the ultimate form of contribution in a community. For someone to reach that level, they have to be so invested, so committed to the community, that they are willing to put in their time, energy, and resources to own some element of creating and facilitating the community experience.

One of the most common leadership programs is where companies empower members of the community to run a local chapter in their city, organizing events and experiences under the brand umbrella.

We've spoken about a few of these kinds of community programs already. Duolingo's 2600+ monthly language events are run by these kinds of local leaders. Google has over 1,000 Google Developer Groups around the world, Salesforce has hundreds of Trailblazer chapters, Rising Tide Society has over 400 chapters – all volunteer run and under the official stamp of the brand.

To ensure that your leaders can be successful, you want to provide them with as much guidance and support as possible. These programs always have some sort of playbook that guides leaders on what to do, what the expectations of the program are, and how to be successful.

You'll want to make your playbook as detailed as possible. I once reviewed the TEDx playbook that TED gives to its local organizers and it was well over 80 pages. TED events are highly produced and maintain a very high bar of quality, so they guide their organizers on everything from sponsorship policies, to speaker preparation, to stage design, and anything else they need to know to run a TEDx event.

They key to making these programs successful is to take away as much of the work and decision making as possible for your leaders. Make it as easy as possible for them to host successful events, and to focus on the decisions that matter most for their local communities.

You'll also want to create a community space for your local organizers to connect and share tips with each other. Our CMX Connect hosts absolutely love to help us onboard new hosts, share lessons learned with each other, and constantly turn to each other for support. Your program will scale much more efficiently if leaders are able to support each other and exchange knowledge.

Where a lot of companies struggle to scale programs like this is when it comes to operations and data. If you have hundreds of local chapter leaders organizing their events on different tools, it becomes very difficult to ensure consistency across the program, and for you to access the data you need to understand who's RSVP'ing and attending your events. Ideally, you can host the entire program on, and have all of your local leaders using, one platform to centralize operations.

There are many other ways for community members to take on official leadership positions. Most large online communities empower loyal members to become official moderators, to help manage the community space. Again, this helps the community team scale their efforts in a way that would be impossible if they had to do it all themselves.

Moderator programs are also going to come with some sort of playbook and education. Make sure moderators have what they need to successfully manage the parts of the community they're responsible for, and teach them how to manage conflict, what to do when there's an issue they can't resolve, and how to take care of themselves so they don't burn out.

Most parts of your community that you want to keep hands on and personalized, but you can no longer handle yourself, can be handed off to community leaders. In the CMX community, we could no longer keep up with personally welcoming the hundreds of members who were joining every month. So we created an official “welcome committee” of community members who volunteer to welcome new members who are at the start of the commitment curve every week, and make sure each member gets a personal message.

Whenever you put someone in a leadership position for your community, you'll want to focus on quality over quantity. You don't necessarily want to make it very easy to become a leader. By having an application and interview process, or requiring some level of experience in the community, you can ensure that they're truly invested in the community. And in your application and interviews, you can validate that they're aligned with the values of your community. These leaders are going to be representing you and your brand, and they will be interacting directly with other community members, sometimes in difficult situations. If they're hosting local chapters, it will take a lot of hard work to get their community off the ground, and they'll need to have the right motivations and skills to get it done. Focus on quality over quantity when selecting leaders. It's much harder to ask someone to step down from their position than it is to vet them thoroughly in the first place.

Notes

- 1. D. R. Conner and R. W. Patterson, “Building Commitment to Organizational Change,” Training and Development Journal 36, no. 4 (1982): 18–30.

- 2. Albert Pepitone and Leon Festinger, “A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance,” The American Journal of Psychology 72, no. 1 (March 1959): 153, https://doi.org/10.2307/1420234.

- 3. Suzi Nelson, “How DigitalMarketer Activated 44% of Silent Community Members | Case Study,” DigitalMarketer, March 18, 2020, https://www.digitalmarketer.com/blog/activate-community-members/.