Chapter 5. How companies lose touch

Your most unhappy customers are your greatest source of learning.

Companies tend to lose touch with customers as they grow, for a variety of reasons. Companies must find ways to create, maintain, and develop deep connections as they grow.

Why Do Companies Lose Touch?

Running through every business success story is a common theme: stay connected to customers, stay connected to your market, anticipate and expect change. This seems pretty obvious. It’s simple and it’s easy to understand. Customers, after all, are the one thing no business can do without. They are the key to every company’s survival.

Paying attention to customers seems like such a fundamental thing. So why do so many companies do it so poorly? How do companies lose touch with their customers, and lose their grip on the realities of the marketplace?

As any athlete will tell you, just because something’s fundamental, that doesn’t mean it’s easy.

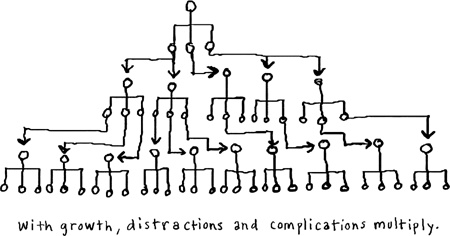

Without question, customers are the single biggest factor in any company’s long-term growth and profitability. And yet, as companies grow, distractions multiply. Success can create such a dazzling array of opportunities that companies try to capitalize on too many of them, over-expanding and diluting their offerings. Internal efficiency and organization become paramount as companies struggle to maintain their growth trajectories and keep the factories and supply chain moving. Political squabbles can erupt as people jockey for status, attempt to seize greater authority and control, or take credit for successes. Bureaucracies that emerge to handle increasing complexity and organizational challenges can also stifle creativity and innovation.

Focusing on the complexities and intricacies of growth, many companies take their eyes off of the customer, their most important asset.

Ironically, a history of success may be the biggest reason companies lose touch with customers. Success can fuel enormous growth and even lead to market dominance. But it can also lead to over-expansion, blind spots, and risk-avoidant cultures.

Over-Expansion

Caught up in whirlwind growth, some companies become distracted by a landscape of opportunity and try to do everything just because they can.

How Starbucks Lost Touch

In the early 2000s, Starbucks focused on growth, expanding globally, opening new stores, and populating their stores with more and more products, like songs and books. New stores were opening every day, and a seemingly endless parade of new products entered stores, until every Starbucks seemed to double as a gift shop.

“Obsessed with growth, we took our eye off operations and became distracted from the core of our business,” says Howard Schultz, Starbucks CEO, in Onward: How Starbucks Fought for Its Life without Losing Its Soul (Rodale Books, 2011).

“Every new store increased the company’s profits, and every incremental product increased sales and profitability in each store. It wasn’t any single new store or new product introduction that hurt the company, but as these incremental changes added up, Starbucks slowly lost touch with what its customers cared about—fast, great service, great coffee and a place to enjoy it.”

Schultz recalls a day when he realized the need for change.

“Once, I walked into a store and was appalled by a proliferation of stuffed animals for sale. ‘What is this?’ I asked the store manager in frustration, pointing to a pile of wide-eyed cuddly toys that had absolutely nothing to do with coffee. The manager didn’t blink. ‘They’re great for incremental sales and have a big gross margin.’ This was the type of mentality that had become pervasive. And dangerous.”

Schultz called this “hubris born of a sense of invincibility.”

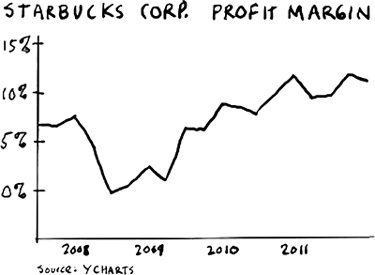

In 2008, Starbucks closed 600 stores, narrowed its product line, and temporarily closed stores around the world to retrain employees on how to make a great espresso.

Since 2008, Starbucks has refocused on its core business; profits are up, and most investors are bullish.

How Krispy Kreme Flamed Out

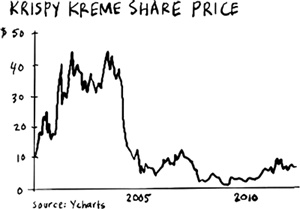

It seemed as if Krispy Kreme had created the perfect business with all the right ingredients: a secret recipe, donuts that tasted so good they were addictive, and media that had a crush on the company. Krispy Kreme had grown organically since its founding in 1937, and after going public in 2000, the company entered into a phase of aggressive growth. It opened a flurry of new stores, selling its donuts in convenience stores, drug stores, gas stations, and big-box retailers like Walmart. The company’s stock more than doubled in the two years following its IPO. New store openings were heralded on local news stations and customers lined up outside stores for a first taste of the fantastic donuts. Krispy Kreme’s marketing plan boldly stated, “Our market is everyone, everywhere.”

But the company grew too fast, and spread itself too thin. Donuts, it turned out, might not be so addictive after all. By opening so many franchises so quickly, Krispy Kreme forced franchisees to compete for a limited market. In addition, franchisees were required to buy equipment directly from Krispy Kreme at marked-up prices. But by maximizing its short-term profits from franchisees, Krispy Kreme shot itself in the foot. Many stores struggled to make a profit and some went out of business or had to declare bankruptcy.

Sales dropped. One of its biggest franchisees defaulted on payments and later filed for bankruptcy. Other franchisees also declared bankruptcy, and Krispy Kreme found itself saddled with more stores than it could operate profitably. Krispy Kreme’s troubles worsened when shareholders filed lawsuits, charging company executives with ignoring signs that the company was expanding too quickly. The SEC launched an investigation—never a good sign.

Krispy Kreme stock fell from a high of $50 in 2003 to $3 in 2007.

Krispy Kreme retrenched, sorted out its finances, and settled with the SEC in 2009. Today, the company is expanding again—more cautiously this time.

Blind Spots

While trying to do too many things can be a problem, a focus that’s too narrow can be equally problematic. As companies grow, they increase in expertise and efficiency as they attempt to increase profits and market share. But that expertise can narrow the company’s focus so much that it develops gaping blind spots. When new technologies and business models inevitably come along to disrupt the status quo, the company has stuck all its eggs in one basket.

How Xerox Missed the PC Revolution

In 1970, Xerox set up its PARC (Palo Alto Research Center) to envision and develop the office of the future. To that end, the group was wildly successful and has been credited with the invention of laser printers, bitmapped graphics, the mouse, the graphical user interface (GUI), what you see is what you get (WYSIWYG) text editors, and Ethernet. But when it came to introducing these innovations to the marketplace, Xerox faltered.

Xerox PARC was based in Silicon Valley, a far remove from Xerox headquarters in Rochester, NY. While this gave researchers great freedom to pursue new ideas, it also made it more difficult for them to convey the opportunities to senior executives. At the time, copiers were generating huge profits, and Xerox still saw itself as a copier company.

In a recent interview, Gary Starkweather, inventor of the laser printer and former Xerox PARC researcher, told Malcolm Gladwell: “They just could not seem to see that they were in the information business… Xerox had been infested by a bunch of spreadsheet experts who thought you could decide every product based on metrics. Unfortunately, creativity wasn’t on a metric.”

Apple founder Steve Jobs paid a visit to Xerox PARC in 1979. He was inspired. Xerox PARC engineer Larry Tesler reported to Gladwell: “Jobs was pacing around the room, acting up the whole time. He was very excited. Then, when he began seeing the things I could do onscreen, he watched for about a minute and started jumping around the room, shouting, ‘Why aren’t you doing anything with this? This is the greatest thing. This is revolutionary!’”

Jobs went back to Apple, and the rest is history.

Xerox may have learned its lesson. Today, the company is focused on moving from being a copier company to a services company. Since 2006, revenue from services—such as outsourcing its customers’ document management and other business processes—has risen from 25% to almost 50%. The jury is still out, but Xerox may be turning itself around.

How Kodak Faded Away

Kodak introduced one of the first consumer cameras in history, in 1888, with the slogan, “You press the button, we do the rest.” For 100 years, it sold cameras and film. Its highly profitable business was based on the classic “give away the razor and sell the blades” strategy: it sold cheap, easy-to-use cameras and reaped profits from the film business over time.

In 1975, Kodak engineer Steve Sasson invented the world’s first digital camera, a prototype cobbled together using existing technologies, including a super-8 camera lens and cassette tape. After taking your photos with the camera, you could remove the tape and put it into a playback device to display the images on a standard TV. He and his colleagues demonstrated this “filmless technology” to Kodak executives throughout 1976.

But Kodak had a blind spot when it came to anything that might disrupt the company’s profitable film business. Sasson reports the executive reaction: “Why would anyone ever want to view his or her pictures on a TV? How would you store these images? What does an electronic photo album look like? When would this type of approach be available to the consumer?”

Sasson and his team did not have the answers. But by applying Moore’s law, the team came up with an estimate: In 15 to 20 years, the devices would be available to consumers.

Kodak sold low-cost cameras but made the lion’s share of profits on film. The company’s core product was threatened, and Kodak had a 15-year head start to figure out what to do about it. What did Kodak do? Nothing.

Over time, it became more and more evident that the predictions were coming true. In 1988, the JPEG and MPEG formats were introduced. Consumer digital cameras followed in the 1990s. While Kodak’s film business faded, the giant slowly awoke, and the company struggled to find a strategy. One Kodak Senior VP and Director of Research said in 1985: “We’re moving into an information-based company, [but] it’s very hard to find anything [with profit margins] like color photography that is legal.”

In the early 1990s, CEO Kay Whitmore vowed to “set the standard in film-based digital imaging.” You may ask, as I did, “What’s film-based digital imaging?” One example is the Photo CD. Customers could take film to a processor and get a CD back instead of prints. They could then view the CD on their TV with a special player. Kodak executives met with technology companies, trying to find a way to partner. (Bill Gates remembers Whitmore; he remembers Whitmore falling asleep in a meeting.)

More “strategies” followed. First digital cameras, but it turned out the margins in that competitive industry were way too thin. Next, online services to help people manage their photos. Today, it’s cheap inkjet printers.

No doubt, times are tough in the film business. But consider rival Fuji. As early as the 1960s, it was producing videotape, computer tape, and audio cassettes. In the 1970s, it was selling VHS tapes and floppy disks. In the 1980s, Fuji started an Electronic Imaging Division and introduced the first digital, computerized X-ray system as well as the world’s first consumer digital still camera.

Today, Fuji is building on its experience and expanding into other industries, such as medical systems, digital imaging, optical devices, and specialty materials like the thin films used in making flat-panel displays and solar cells.

Fuji stayed in touch with customers and the changing market. In January 2012, Kodak filed for bankruptcy.

Risk-Avoidant Cultures

When a company is large and successful, its size can be its worst enemy, especially when it is so dominant that it lacks serious competition. A company culture that drove success in the early days can become overly codified, rigid, and ritualistic. Over time, bold new moves become much more risky; new business models may compete with existing businesses and cannibalize their sales. Even when it’s obvious that change will someday be necessary, it’s not hard to find excuses to put it off just a little bit longer. Slowly, great companies can lose touch with reality.

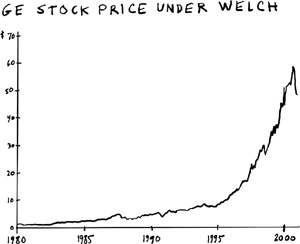

How GE Revitalized its Business

GE was founded in 1890 by inventor Thomas Edison, and over time it grew to dominate many industries, including power generation, turbine engines, electrical appliances, and many others. When the Dow Jones Industrial Average was created, GE was one of the 12 companies listed (it’s the only one of the original 12 that still exists).

Bureaucratic rigidity reigned supreme when young executive Jack Welch moved into GE headquarters in 1974. In his memoir Jack: Straight from the Gut (Warner Business Books), he remembers that, “a set number of ceiling tiles signified one’s status in the corporation.”

There were as many as a dozen layers between the CEO’s office and front-line workers. All those layers insulated the company’s executives from its customers, like a person who was wearing too many sweaters. Says Welch, “When you go outside and you wear four sweaters, it’s difficult to know how cold it is.”

In GE’s power business, says Welch, “There was an attitude that customers were ‘fortunate’ to place orders for their ‘wonderful’ machines.”

“The bigger the business, the less engaged people seemed to be. From the forklift drivers in a factory to the engineers packed in cubicles, too many people were just going through the motions. Passion was hard to find.”

A mid-70s tour of Japanese manufacturing plants galvanized Welch into acting early and proactively, while the company was still healthy and profitable:

The incredible efficiency of the Japanese was both awesome and fright-ening…And the Japanese, benefiting from a weak yen and good technology, were increasing their exports into many of our mainstream businesses from cars to consumer electronics. I wanted to face these realities.

“I came to the job without many of the external CEO skills,” says Welch, “but I did know what I wanted the company to ‘feel’ like. I wasn’t calling it ‘culture’ in those days, but that’s what it was.”

Change wasn’t easy. In fact, it was war. Welch declared war on the bureaucracy and entitled culture at GE. “I was throwing hand grenades, trying to blow up traditions and rituals that I felt held us back.”

He cut the levels of hierarchy in half and instituted a competitive, performance-oriented culture, insisting that top achievers were rewarded handsomely and low performers were fired. The strategy he laid out was to focus only on industries where GE could be number 1 or number 2. If they couldn’t be number 1 or 2, they would fix, sell, or close the business.

In Welch’s 20 years as CEO, GE refocused on customers and market realities and grew revenue from $27 billion to $130 billion while increasing profit margins. GE has been consistently profitable since 1991.

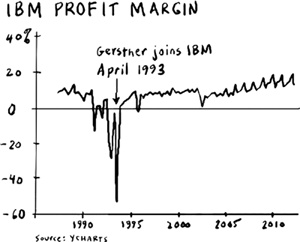

How IBM Rediscovered Customers

IBM was also founded in the 1800s. Its early “business machines” included scales, electric tabulation machines, and company time clocks. As the company grew, it continued to focus on its business customers and helping them process and manage the data it took to run their businesses. IBM successfully managed to stay ahead of the technology curve for most of its history, combining investments in R&D and innovation with customer service and support for its complex, leading-edge technologies.

But by the early 1990s, the company’s culture had atrophied into an internally-oriented, ritualistic web of territorial fiefdoms. IBM’s sales and profits were falling at an alarming rate. They needed a change agent. In his book Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance? Leading a Great Enterprise through Dramatic Change (HarperBusiness), Lou Gerstner remembers the culture he inherited in 1993:

An institutional viewpoint that anything important started inside the company—was, I believe, the root cause of many of our problems…They included a general disinterest in customer needs, accompanied by a preoccupation with internal politics. There was general permission to stop projects dead in their tracks, a bureaucratic infrastructure that defended turf instead of promoting collaboration, and a management class that presided rather than acted.

Gerstner didn’t come from inside the company. He was an outsider and former IBM customer as CEO of American Express. As a customer, he had been enormously frustrated by IBM’s territorial geographic structure:

The fact that American Express was one of IBM’s largest customers in the United States bore no value to IBM management…It was enormously frustrating, but IBM seemed to be incapable of taking a global customer view or a technology view driven by customer requirements.

One of Gerstner’s first moves was “Operation Bear Hug,” in which every member of the senior management team, and every one of their direct reports, visited at least five of their biggest customers in a three-month period, to listen, show the customer they cared, and initiate action as necessary. For every visit, Gerstner wanted a one- to two-page report sent to him and anyone in the company who could solve that customer’s problems.

The prevailing plan when Gerstner came on board was that the company should be broken apart into individual businesses—so-called “Baby Blues”—so they could compete more effectively. But Gerstner took a different tack.

Realizing that IBM’s strength with customers came from its global reach and broad, deep expertise, he reorganized the company from geographic territories into global, customer-oriented segments that cut across geographic lines. Like Jack Welch’s “hand-grenade” approach at GE, this was tantamount to a declaration of war. IBM regional managers were like powerful heads of state, and resisted him at every turn:

During a visit to Europe I discovered, by accident, that European employees were not receiving all of my company-wide e-mails. After some investigation, we found that the head of Europe was intercepting messages at the central messaging node. When asked why, he replied simply, ‘These messages were inappropriate for my employees.’ And: ‘They were hard to translate.’

One particularly stubborn—and inventive—country general manager in Europe…simply refused to recognize that the vast majority of the people in his country had been reassigned to specialized units reporting to global leaders. Anytime one of these new worldwide leaders would pay a visit to meet with his or her new team, the country general manager, or GM, would round up a group loyal to the GM, herd them into a room, and tell them, ‘Okay, today you’re database specialists. Go talk about databases.’ Or for the next visit: ‘Today you’re experts on the insurance industry.’ We eventually caught on and ended the charade.

Changing the culture was the key to the transformation. Gerstner, like Welch, wanted a high-performance culture. “Culture isn’t just one aspect of the game—it is the game,” he says.

But culture isn’t something any one person can control. It lives and breathes in the actions and behaviors of every person in the company, and it’s acted out every day. Culture is deeply embedded in the ongoing habits and routines that permeate any company. Changing a culture is a Herculean task and it doesn’t happen overnight.

“You can’t mandate it, can’t engineer it. What you can do is create the conditions for transformation. You can provide incentives. You can define the marketplace realities and goals. But then you have to trust. In fact, in the end, management doesn’t change culture. Management invites the workforce itself to change the culture,” says Gerstner. “Frankly, if I could have chosen not to tackle the IBM culture head-on, I probably wouldn’t have.”

Luckily, he did tackle it, and persistent effort paid off. Between 1990 and 1993, when Gerstner took over, IBM lost $16 billion. In his first year, he rescued IBM from its steep dive and returned it to profitability. The company has grown steadily ever since.

When in Doubt, Get in Touch with Your Customers

Name a company you love, a company you are loyal to, a company you buy things from all the time, and you will inevitably find a company that’s connected to its customers, that knows who they are and what they care about.

Focusing on customers doesn’t mean trying to please everyone. It’s about getting a deep sense of who your customers are and what they care about. Walmart dominates retail by relentlessly focusing on price-sensitive customers. Everything in Walmart’s culture is focused on squeezing one more penny of cost out of their operations, and sharing those cost savings with customers. Much smaller retailer Nordstrom has only 2% of Walmart’s revenue, but generates higher profits by focusing on customers who prefer excellent service and selection over price. Walmart and Nordstrom focus on two profitable but distinct market segments, while other retailers who try to be too many things to too many people, like Sears and JC Penney, get squeezed.

The world is constantly changing, and so are customers. Customers won’t always want any one product or service. They won’t always want iPads.

But some things won’t change. There will always be customers who want great experiences, great service, convenience, selection, low prices, and fast delivery. A customer-focused company knows what its customers care about and builds capabilities and strategies that reinforce its advantages over time.

GE, IBM, and Starbucks turned their companies around by focusing on customers. Kodak continues to struggle—the company’s latest bet is using its patent portfolio to finance a line of cheap inkjet printers it hopes will save the company. Kodak investors are understandably skeptical, and the company’s stock today is trading at all-time lows.

There’s an old adage about making difficult decisions: “When in doubt, go towards the fear.”

When you are facing a difficult decision, more often than not you know deep down what direction you need to take. But when that direction is risky, or difficult, or otherwise scary, people look for reasons to avoid the difficult road. So lurking within most difficult decisions is trepidation and fear about the road you must take.

We can only imagine what the decision makers at Kodak must have felt when they realized the future of photos was filmless. The fear must have been palpable. But at the same time the imperative must also have been evident: start getting out of film and preparing for the digital world.

Unfortunately, we can all too easily imagine the meetings and memos that rationalized away the fears, the people hanging on to near-term retirement, the desperate hope that by some miracle, the world would not evolve.

When in doubt, don’t look inside your company for answers. Turn around and face the market. Get back in touch with your customers.