Conclusion

Wealthy Nations, Healthy Global Firms

“What is essential in the transitional period is not the fact that technical progress causes disruptions (…) but that it constantly changes the individual.”1

Jean Fourastié

Without forgetting the trade in manufactured goods and raw materials that marked the 20th Century, economic exchange is including more and more services and data flows, and intangible values such as software or brands. Today, exchange is no longer bulky; it relies very much on abstractions, intellectual property, financial products and, more recently, cyber-currencies. Transactions increasingly focus on intangible values; and less on tangible products that have represented wealth and temporal power for so many generations: gold, silver, land, printed bonds or bearer shares. Previous chapters illustrated the variety and rapid growth of this new category of transactions, often on a global scale. This change goes beyond what we could have anticipated 40 years ago, when we began to become aware of computerization and its consequences on the organization of society. Production, trade and creation change form and purpose; this phenomenon, described as a “new economy” for several years, is illustrated by fairly recent but already global companies such as Apple, Amazon, Alphabet and Microsoft. Through contagion or imitation, other digital giants like Alibaba and Baidu, which were developed in the Far East, also symbolize the recent reign of platforms.

Driven by the conquering technology of computers and networks, this evolution challenges many of the notions that we have learned in order to describe the economy and reveal its springs. Disruption seeps in everywhere; it creates a climate that concerns some; but it also stimulates a lot of creative energy2. The time has therefore come to integrate the symbols of this “new economy” into the political economy, for wealth is no longer embodied in things, but also in abstractions such as digital data and computational procedures that are quite frequently mentioned in several of the previous chapters. Henceforth, the real challenge should no longer be to accurately describe the contemporary economy with yesterday’s accounting tools, but to understand and measure trade and innovations that are characterizing the 21st Century with the appropriate tools!

Economics: a perpetual renewal…

To avoid being overwhelmed by faster or more innovative competitors, every firm is forced to adapt to the changing environment in which it operates and imagine technical and practical innovations that exploit technical progress, in order to constantly renew its offers. Joseph Schumpeter highlighted this disruptive process and presented it as characteristic of modern capitalism; he became aware of it after a strenuous analytical journey which resulted, in his own words, from “forty years of deliberations, observations and research on the theme of socialism3”. Formulated during the Second World War, the Schumpeterian oxymoron (can one both destroy and create?) accurately explained the rise of the “Thirty Glorious Years” and the reconstruction of a competitive industry in Western Europe and Japan in the aftermath of the Second World War. Seventy years later, this unforgettable aphorism can be applied to the digital economy because it reflects the turmoil induced by Internet platforms and operators thriving on the network of networks. From a less traditional perspective, we can even consider that some of the innovations of the digital era are changing social behavior and will transform some economic institutions in the near future4.

As early as the 1960s, Kenneth Boulding bravely proposed “rebuilding the economy” solely on the basis of corporate accounting, as he claimed that these basic data, which were specific to each operator, truly represented production, trade and wealth. In other words, the scrupulous observer of economic phenomena should limit himself to being an impartial spectator who describes, analyzes and summarizes facts and behaviors of economic agents ([BOU 62], pp. 3, 172–173)5. Correlatively, this author also stated that the granular economic data collected in the field that are made of aggregate indications and on which the political economy is based, should feed a vast “human science” that will make it possible to fully understand the “ecosystem” of the biosphere ([BOU 62], p. 7)6. This heterodox mind thus linked economic analysis to concrete facts; he relied on political economy to depict reality more faithfully than sophisticated models and equations summing up the world7.

The emergence of multinationals

This very same issue is back again in a different context to that which prevailed in the 1960s; Chapter 7 has set some benchmarks in this regard: beyond the metrics or methods which can amend the assessment of economic activities (particularly those linked to digital technology). For decades, the scale and scope of industrial production has been profoundly broadened with global and open markets. Large, concentrated and diversified multinational companies are truly essential worldwide; in their wake, these firms bring about an array of services and subcontractors that drive the activity in many countries, among which production and added value are distributed: Eastern “tigers”, Eastern European countries, South American and African territories, to name a few.

It is obvious that the activity of multinational companies cannot be limited to a particular territory; the electronics firms are only one example among others; this loosens the ties that companies formerly maintained with the land from which they came from. Present global firms buy, sell, manufacture, subcontract and trade everywhere. Their management acts and thinks in a truly global perspective, far beyond the nation-state(s) in which they were born. Although firms sometimes return to their native territory to get through a difficult period (as was the case of the Korean chaebols put in difficulty during the Asian crisis of 1997 and the Hyundai group in 2017), their multiple interests and their competitiveness force them to distribute assets, means of production and markets internationally. Their large size, diversification and risk distribution go hand in hand with means and strengths that largely transcend the perspectives and policies of the countries where they produce and distribute their services or goods8. This raises multiple issues and sometimes very sharp reactions, which are specifically linked to the concentration of these companies and the conditions of competition, where their position is very strong. For years now, multinational firms have contributed to the diversification and growth of world trade; their direct investments supported the development of many territories; they have opened up international trade considerably.

While the first globalization that transformed the world more than a century and a half ago moved goods and raw materials across the world’s seas, the cross-border redistribution of investment and manufacturing production characterized the second wave of globalization that occurred during the last 30 years of the 20th Century. More recently, information and communication technologies stimulated a “third wave” of globalization which took off around 1970, and which has become widespread since the appearance of the Internet around 1995 ([CHA 80], p. 85; [BAL 16], p. 45). Today, IT and digital companies (components, platforms and associated services) are attracting attention because of the contribution they make to our personal and professional lives; their performances are emblematic of this third wave of globalization: they sometimes significantly reverse the comparative advantage of the various regions where their presence (and the technology that they support) promotes change. The authors of this volume, like many other scholars, insist on three points that must be taken together:

- – the digital market is dominated by megafirms that are active all over the world;

- – concentration (through own growth, buyouts, takeovers or mergers) builds up turnovers and results in multi-billions, especially in the communication sector9;

- – the rate of profit and market capitalization of these firms grow higher and quicker than what was allowed by previous industrial activity.

Mega-companies, often American

The doctrine is divided on the causes, consequences and lessons to be drawn from these three findings. Since its inception, computerization has been dominated by American industries. The famous French report: “L’informatisation de la société” [NOR 81] took note of the dominant position benefitted by IBM at the time, but without yet imagining that this company, dating back to the 1920s in its modern form, could have a change in fortune10. Has Microsoft software not also been ubiquitous in computer systems, at least in personal computers, office automation and word processing, for many years? Just like how IBM processors dominated the computer market in 1970, our present electronic assistants are now organized around Intel processors (sometimes AMD) which reveals temporary unquestionable dominances; it is therefore difficult to see at present, just as in 1978 with the then dominant firm IBM, who could overturn this dominance! Of course, China’s spectacular industrial and commercial investment effort, supported by a mercantilist industrial policy, is producing results (Huawei); but, despite the promises of openness that China accepted by joining the World Trade Organization (WTO), this country benefits from an enormous and deeply protected domestic market, and gives its counterparts some concerns without yet having the competitive capacities of a Korean company like Samsung11!

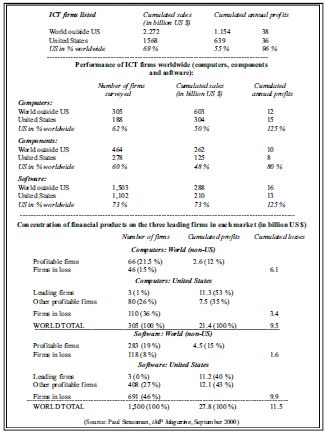

Table C.1 shows that the dominance of American IT manufacturers and software is not new: at the end of the 20th Century, the near 1,500 American companies listed here generated 55% of the world turnover of the information industries; their profitability clearly exceeded that of non-American companies, a significant number of which were either loss-making or subsidized: 96% of world profits in the sector therefore failed American companies12. Strassmann, author of the study mentioned here, proved that in the two main segments of this branch (computers and software), the three leaders (IBM, HP and Dell for computers; Microsoft, Oracle and Cisco for software) took more than half of the world’s profits13! The prominence of American megafirms in the digital sector has not ceased since 2000: despite a major renewal of hardware manufacturers, software houses and electronic components. Some startups, that were unknown or almost unknown in 2000, dominate today (like Asus or Google); other companies have either disappeared or regressed (like Motorola or Yahoo!); and as IT, telecoms, video games, broadcast and platforms are not immune to the effects of scale, concentration is again increasing. Moreover, when circumstances are favorable, companies can increase both their turnover and their margins, which strengthens their dominant position (as is currently the case for Microsoft, Apple and Google).

Table C.1. Global dominance and concentration of American IT firms

COMMENTS ON TABLE C.1.–

- – concentration highlighted by these tables is obviously different from the one that could be established for 2017. Some of the current leading companies were unknown in 2000, because Internet platforms were non-existent (Facebook) or in their infancy (Google). However, the mechanisms that promote concentration today are similar to those that led to the concentration of electronics, computing and communication some 20 years ago;

- – figures above are in U.S. dollars. We did not mention the exchange rates applicable to non-U.S. companies that work with other currencies. Firstly, because of the prominence of dollar transactions on these markets; and secondly, because the turnover and the profits of American companies are of a much higher order than those of other global companies.

Although this concentration is understandable, it undoubtedly raises issues because Moore and Rock’s laws (discussed in Chapter 6) apply to the chips industry and to most activities that depend on it; a narrow club of industrialists is therefore at the forefront of this industry, thanks to very high investments and very rapid capital turnover; the operating risk that renews itself with each generation of electronic chips imposes this strong capitalization, encourages concentration and requires a cross-border market. This was confirmed since 2000. Downstream of the components, the design, assembly and development of computers, game consoles and personal assistants such as the iPhone or Samsung Galaxy are also subject to empirical laws that promote industrial concentration. Chapters 1, 3 and 4 have evoked these disruptions in various forms, and Chapter 5 depicts the iconomic transition that generates a quantum leap between the past and the future. Concentration and disruption are thus the common lot of digital manufacturing industries.

Software, in the broad sense, is more heterogeneous than manufacturing: it includes market companies and non-market organizations; peer-to-peer (free software and blockchains) and community projects such as Wikipedia, as well as collaborative economy, crowdfunding, crowdsourcing and blockchains as discussed in Chapter 4. Because of this diversity, some segments of the digital economy may escape concentration; but club, network and scale effects remain significant everywhere14. Even the leisure and entertainment media are disturbed, as clarified in Chapter 2, which describes the dividing lines within the media between professionals and amateurs on one side, and between craftsmen and large groups on the other, for example in the cinema; the same is true of service activities, whether they are disinterested, cooperative or commercial.

Diversity of situations

The diversity of situations is therefore great; the most active operators (who are sometimes, but not always, the richest!) are pushed to join forces or buy out start-ups, which leading companies like Alibaba, Apple, Amazon, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, or even Tesla or Twitter do daily. History often suggests a fear that these concentrations towards a potential monopolization could bypass competition and market mechanisms. However, things are not that simple. Not all mergers prepare for global success, quite the contrary. There are counter-examples: in telecommunications, the MCI-Worldcom case ended in fraudulent bankruptcy15; furthermore, two major acquisitions of Microsoft have not only proved that the biggest companies do not win every time, but also that such operations can destroy part of the accumulated wealth. Between 2011 and 2017, the attempt to integrate the Swedish company Skype into Microsoft, followed by the costly purchase of the Finnish telephone company Nokia in 2016, resulted in a questionable or mixed result (Box C.1). Thus, nothing is set in stone, even for billionaire stock market stars!

This requires thought about the counterparts that a strong market position, a high profit margin and unbridled ambition can have for the general public. Should concentrations be systematically sanctioned? Should preference be given to measures that prevent the abuse of a dominant position and limit economic concentrations?

American antitrust

For American law, predatory behavior is defined by a simple criterion, that of harming the interests of consumers. Those who fight against the growth of the GAFAM and wish to dismantle them for reasons of principle distort American law, unless they demonstrate that it is the concentration of these companies that harms the consumer, as a Commissioner of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) put it bluntly: “The fact that industry concentration and firm profits trend upward for a time does not show that competition is in decline. The causal chain between market structure and firms’ economic rents is complex and multi-directional” ([OHL 17], p. 62). Thus, if the Google search engine and the iPhone, iBook, iTunes, and such services designed by Apple satisfy the user, nothing really stands in the way of these companies’ growth! In the end, as long as the user is not an obvious victim of the concentration, the latter is not inherently condemnable [SHA 17]18. In a synthetic test, this expert from the FTC and the U.S. Federal Justice points out that nothing specific condemns dominant companies just because of their size, as the U.S. jurisprudence targets:

- 1) cartel control, a provision that has been somewhat fallow for a quarter of a century because it is difficult to implement, although it concerns essential abuses;

- 2) horizontal mergers (between firms in the same market segment), which have become more flexible since 1982 and deserve less effort since megamergers have proved dubiously effective in practice; mergers even tend to be regulated naturally19;

- 3) excessive market power, an excess that is commonly attributed to the GAFAM but always very tricky to prove as it requires solid evidence that the consumer suffers actual damage, proof that is long, difficult and costly to report; this might explain why so few cases were investigated during the last 25 years on that ground;

- 4) break up of a giant firm in order to rectify clear damage suffered by the consumer; but here again, the causation between the size of the provider and the damage is also quite difficult to prove;

- 5) incidentally, regulation of electronic medias and communication, which faces multiple difficulties that have been identified for a long time in America20. In the case of intensive use of personal data (big data on individuals, their behavior and their habits), from which platforms take great advantage, normative provisions may mainly force the operators to avoid privacy trouble21.

A tricky tool to handle!

It follows from the above that caution should be exercised in the face of economic concentration or dominant positions of companies involved in the digital sector. Moreover, the European market only has a very limited number of operators whose products or services could take precedence on the international scene in this area; European consumers thus mainly turn to American suppliers who seem to respond to their demands well enough. Truly, European antitrust rules may apply to American companies; but it is always difficult to judge the effect that a binding measure could have on companies whose services are favored by the population and by businesses22! Would binding measures for these companies generate unforeseen effects in Europe? Would they turn, for example, against the interests of those consumers we wish to protect, such as the case of so many Europeans consuming this type of U.S. based service23? In such matters, caution matters in Europe. Especially given that these platform providers are American and that their home country has both the longest experience of industrial and financial concentration, the oldest antitrust legislation, the most extensive antitrust jurisprudence and a credible federal justice in terms of cartel control and detection24.

The digital era is characterized by strong interdependence. The major European players are taking advantage of globalization, including digital tools and services (aeronautics, space, energy, automobiles, banking, machine tools, etc.). A strict European procedure could complicate the European firms and consumers access to these platforms and services they are currently using. It would thus be prudent for the European Commission to avoid misusing the deterrent it holds in terms of concentrations and dominant positions, for fear of harming the Europeans themselves deeper than they may hurt the Gafam!

Cyber-currency and blockchains: a dynamic field

For nearly three centuries, political economy treaties have devoted lengthy developments to currency, its role, the services it renders, the conditions under which it is issued and its value. Turgot (1727–1781) for example, considered that any commodity could be used as currency, but that to be a credible means of exchange and a sustainable store of value, currency had to be based on another commodity that was already valued for the services it rendered (for example, gold or silver). For Adam Smith, a few years later, currency was little more than a useful intermediary to stimulate exchange because, for him, work was the only real and definitive measure which could be used, in all times and places, to appreciate the value of any merchandise25. As for Pigou, he stated clearly: “By money, I mean legal-tender money; and by the value of money, I mean the exchange value of a unit of it […] in terms of commodities”26. The modern monetary doctrine, which is not really new, is more flexible: it recognizes that currency is, simultaneously, a unit of account, a standard of value, a means of exchange and a store of value. Anything that is accepted as payment for a good, service or obligation, whether cash or on credit, can therefore play the role of currency as long as it is not rejected by use. Such a currency is obviously sensitive to supply and demand. However, it also fluctuates according to circumstantial parameters that favor its use or rejection ([ROB 22], pp. 2–3)27.

Cyber-currency is a monetary sign!

For the sake of clarity, let us apply the preceding definitions to new signs such as the bitcoin or ether: these signs, that are associated with a digital blockchain, do not meet the classical criteria of currency. They are not goods, as defined by Turgot; they do not represent any labor value, as defined by Smith; they do not fall within the definition put forward by Pigou and the economists of the interwar period, for whom currency can only be legal tender28. It is a different story if we relate cyber-currency to the pragmatic definitions of an Englishman like Robertson, whose views inspired generations of financiers. His sharp view on currency would have inevitably led him to admit that the bitcoin and ether satisfy the conditions summarized above: they are widely accepted as means of payment; they serve as means of exchange and reserve; moreover, their unit can be perfectly divided. However, unlike legal tender, they have no link with a political or monetary authority, they are not attached to a territory nor to a tutelary authority, and they exist outside and despite political conditions. They are thus, in the literal sense, private a-territorial and apolitical currencies, defined by the partnership contract that gave birth to them. Accessible to everyone, managed by a community that keeps a faithful and lasting record of transactions recorded on the blockchain and that ensures visibility in an open cyberspace, they move freely!

Additional questions: How is the value of these monetary signs determined, according to what principles, and why does it change so rapidly over time29? Regarding this, we must distinguish two situations: that of decentralized currencies such as the bitcoin, which are issued over a long period and under the conditions provided by their founders, and for a final amount defined in advance (a fixed number of the cyber-currency unit). And that of centralized currencies, which are issued by a central authority such as Ripple. In the first case, the currency is issued over time until it reaches the money supply provided for in the partnership agreement, which the founding agreement sets in advance (21 M. BTC, for example). On a daily basis, new signs compensate mining with a premium that awards the actual formation of new blocks30. However, in the second case, the money supply circulates as soon as the money is created; the issuing organization is compensated by the commissions it receives on the transactions that are recorded in the blockchain over time.

The consequence, in either case, is that there can be no monetary creation other than that provided for by the founding agreement, which averts any inflation of the monetary sign. However, the value of cyber-currency varies according to a number of circumstantial factors: the strong or weak demand for money, the opportunities for use or investment that it allows, the accidental or political risks that threaten its technical system, and so on; the constraints that could restrict the use or circulation of this currency, or even impose on its holders to abandon it, are obviously a relevant factor. The volatility31 of these currencies is directly related to these risks, to their scope of application and to multiple exogenous factors such as the penalization of the holder, or the taxation of capital gains by holders of cyber-currencies in some countries32.

What are cyber-currencies used for?

The emergence of cyber-currencies should no doubt be seen as a continuation of the turmoil that has shaken sovereign currencies since the disappearance of the monetary stability, that previous generations still dreamed of at the time of the Bretton Woods agreements (1944). In fact, no contemporary currency can escape the risk of being manipulated by the tutelary authorities, in favor of macro-economic or socio-political objectives; moreover and beyond public policies and monetary regulation, constant financial innovations have accelerated monetary creation in proportions that are beyond comprehension, particularly since the 2007–200833 crisis; lastly, the emergence and maintenance of very low or even negative interest rates on currencies, such as the euro and the Swiss franc, are deceiving savings and disrupting the distribution of pensions based on capitalization, while the population of pensioners is still increasing. Private monetary signs such as the bitcoin thus came at the right time in 2009, in order to meet a demand for cash that would escape political uncertainties and zero or negative returns from legal-tender money. In this context, cyber-currencies are gradually becoming part of the financial landscape. For the time being, they respond to niche requirements: for example, that of compensating for the lack of foreign exchange in survival economies such as the one in Venezuela34; or of escaping the meticulous control of foreign exchange in China or in deriving African countries.

However, voices are being raised to criticize the bitcoin on the pretext that this cyber-currency would facilitate the setting up of “Ponzi schemes”, swindles which promise excessive remuneration to a gullible public whose first subscribers receive a magnificent contribution, which actually comes from the funds paid by the last subscribers, who have to pay to clean up the mess as soon as the deceit is revealed. It must be pointed out that these scams are as old as the world, that they were very much here before the bitcoin spread throughout contemporary history and that they particularly prospered under the exclusive reign of state currencies! In addition, these large-scale frauds are now flourishing in Asia, to the detriment of populations that are still unfamiliar with financial matters: many Chinese savers have been fooled by these fraudulent schemes since 2015; these villainous affairs, which did not in fact need a cyber-currency to exist, have only served as a pretext for the Beijing government to severely repress these deceptions since 2017, and have simultaneously condemned useful uses of bitcoins, which allow trading without constraint, as it bypasses the exchange monopoly enjoyed by the People’s Bank of China (PBC)35! And if cyber-currency disrupts, it is because it escapes central control and allows tokens to be issued that give their holder rights over activities in making or sharing a business project, a project that does not necessarily fit in with the political planning of the Communist Party and the Chinese government36.

Blockchains, Ledgers and institutional innovation

Bitcoin and cyber-currency have attracted a lot of attention since 2016; but truthfully, they are only the emerging part of a very important software and behavioral innovation that also needs to be appraised in non-monetary terms. Functionally, the bitcoin system and its variants are based on a “Ledger”37, where multiple transactions are reported over time: financial and monetary transactions, of course; but also, administrative, conventional, real estate or even intangible transactions on copyright, trademarks or patents, where appropriate. These computer records are permanent, accurate and decentralized. They keep a distributed record of any obligation, act or fact whose history is to be established and monitored over time: personal civil status, land properties, car plates, models, company statuses, business or trade contracts, tax or customs forms, production or maintenance catalogues, loan registers, etc. A blockchain is suitable for such purposes; monetary applications are just a particular use of a general instrument that will certainly retroact on many social functions and on the memory of an organized society38.

Based on computers linked together by the web, a blockchain keeps the trace of past activities in their chronological order and on an encrypted file reproduced in many identical copies on different node computers set in different places39. It can therefore replace the trusted third party who attests to a contract or promise between two or more third parties (typically, in Latin countries: the notary). But also: a public register such as the land register, the commercial register or the civil register (births, marriages, deaths, nationalities etc.); a financial intermediary receiving the payment of a capital or paying a loan; the public offering of a company or a philanthropy, and numerous agreements which mark business life and involve a secure relationship between the parties of a contract.

This has two major consequences: the computing and decentralized commitments Ledger can advantageously replace an administration such as civil status; this tool can also destabilize intermediaries, “uberize” their services and replace a traditional service relationship with a cryptographic record whose security is at least equal, if not superior to that of the trusted third party, for a much lower price! This automation also improves administrative productivity, which is the case whenever a fast and programmable mechanical operation replaces a manual procedure. The blockchain thus induces, in Schumpeterian terms, a “creative destruction” that disrupts the established order as we said before. It opens opportunities that can also upset the institutional order: the notary, the bank, the insurance, the brokers and the mortgage registrar can be replaced by a blockchain that would reduce transaction costs for all the functions it performs; it is therefore a new intermediary, similar to the commercial platforms that bring supply and demand together (Chapter 3) and to the social networks that establish interpersonal or collaborative relationships (Chapter 4). This benefits coordination and cooperation between economic players, both in terms of performance and costs [POT 18].

A double disruption: procedural and institutional

It is widely accepted by economists and historians that technical progress (embodied in this case by a blockchain) overthrows the competitive advantage of economic agents. By offering the economic operator a cheaper and often better service than before, the automated Ledger outdates the previous systems, that of the trusted third parties (embodied in the notary, a public official or a witness). The oldfashioned techniques and previous service providers become obsolete, just as the Airbnb platform upsets the hotel business. This is a procedural destruction.

From an institutionalist or evolutionist perspective, technology helps to discover new terms of acting that can save transaction costs: for example, the blockchain allows us to issue securities paid in ether or bitcoin, jointly with a subscription to the capital of a new company, or with specific rights on future products or services, avoiding the call upon costly financial intermediaries or venture capitalists! Cyber-currency tokens are more flexible than traditional fiat currency savings; public authorities should keep a neutral view of this institutional novelty as some Swiss cantons, the Republic of Estonia and the City of Singapore already did!

In short: a distributed and encrypted register of transactions outdates previous schemes; it allows the reintegration of services that were delegated to others (treasury to a bank, for example) into the company; or the outsourcing of other services such as the Ledger itself. If the blockchain makes it possible to replace costly intermediation with an automatic, stable and permanent procedure, why prohibit it from facilitating the emergence of new companies, even if these services are partly competing with existing institutions?

This disruption nonetheless provokes some strong reactions: clear reluctance and opposition are organized to counter such a change, which is rarely imposed of its own accord. Confrontations are not avoidable; however, their virulence can be lessened by playing on two levers whose effectiveness has been proven: carefully accompany the transition from the old to the new institution, by any appropriate means; and organize the gradual extinction of benefits that become outdated over time (those affected by novelty, such as taxis or licensed intermediaries). A coalition of supportive interests may finally counterbalance the influence of those who fear suffering from change, just as public services have often done when challenged by a new technique, such as the case of traditional telephone networks during the 1980s and the following years, all over the world40!

The administrative functions that a blockchain could provide are already being tested in the Republic of Estonia and Finland; this will provide useful evidence for the future. A summary between traditional institutions such as the land register or mortgages and a decentralized Ledger cannot be excluded41. Within the financial professions, the use of cyber-currencies has sometimes been strongly opposed. However, some large institutions have already shown an interest in this technology and even in cyber-currencies: the quick, safe and cheap compensation that Ripple would allow on the money market does attract attention. Additionally, the issue of various tokens, that are associated with a blockchain, is multiplying in conjunction with existing financial institutions, as we mentioned above about Switzerland and Singapore.

Are we heading for a big upheaval?

The circulation of private currencies and tokens alongside existing monetary securities and products should not ultimately raise any lasting reluctance insofar as, for quite obvious practical reasons, cyber-monetary applications are aimed at niche markets that complement, rather than replace, public currencies. Conversely, the future of the blockchains and their multiple variations is very open. Our medium-term prognosis is that of a Norman peasant: “p’tèt ben qu’oui, p’tèt ben qu’non” (“maybe yeah, maybe no”)! Yes, the idea that the use of cyber-currencies will spread does seem conceivable; but no, they will not mostly be substitutes for fiat currencies; these signs have neither the same range nor the same spectrum of width; a direct confrontation seems unlikely for some time. Similarly, the scope of electronic agreements and associated services seems so broad that it is difficult to see why such experiments should be limited, particularly in a cross-border context for which direct competition with public currencies may easily be avoided!

Tactically speaking, in the short to medium term, it is unlikely that a large private international organization will be formed to replace current electronic clearing systems such as credit cards or Paypal services. Not only because of the technical constraints that currently limit the “scaling up” of bitcoin, or other decentralized e-currencies, the current limits of which will inevitably be exceeded one day, but mainly because any head-on conflict with central banks or with the political authorities of large countries, which are reluctant to yield any portion of their prerogatives in fiscal and monetary matters, would be suicidal. It would take a real Copernican revolution for the nation-states for their leaders to give back an ounce of the monetary liability they still manage: in North America and Europe, the dollar, the pound and the euro are too deeply rooted in usage for their pre-eminence to fade quickly!

In a rather personal review, Erik Townsend compared the bitcoin to the aircraft of the early 1900s, to those “flying machines” so far removed from what an airliner or wide-body jet is today42. Is bitcoin just a transitional object that will quickly end up in the museum of techniques, as this author suggests? In order to control its function (rightly or wrongly? Whatever!), it is inconceivable that a political authority should spontaneously deprive itself of a monetary tool; apart from, perhaps, in the event of a cataclysm that shakes the world to its core, which nobody wants! Townsend therefore suggests not to generalize the new protocols to all monetary uses, but to experiment extensively with blockchains in the hope of getting our society used to this new tool; and at the same time, to seek faster, more adaptive and safer protocols than bitcoin, which, when the time comes, could support a system that is capable of growing in power over time. This approach would, in a way, rekindle Fourastié’s desire to always stick to reality: “Reasoning is the slave of facts and not their master.”43

Public currencies and widespread disintermediation’s big night is thus not set for anytime soon; but perhaps for some point in the future, which encourages patience; it is therefore useful to prepare the grounds so that when the time is right, monetary innovation can enter into a positive-sum game with the existing one. We believe that this preparation will go hand in hand with a thorough renovation of the measurement and observation of economic phenomena because, as we have pointed out, our assessment methods were designed to describe a rather closed economy, and mainly manufacturing productions. This is why, despite their mathematical or conceptual sophistication, classical models give a biased picture of trade and economic ventures of current times, in which an increasing proportion of added value and wealth production are no longer manufacturing (Box 7.5).

For decades now, the real economic circuit has escaped the conventions of the traditional political economy for which resources, income and wealth were not only tied to a territory, but were primarily represented by tangible goods. Innovations such as the bitcoin and blockchains will be all the better integrated into economic practices if we will have previously made the effort to synthesize their usefulness and contribution with all the economic values of our time. This would imply that we value things and people as well as algorithms and imagination; and that we would integrate equipment and machinery into the amenity economy, as naturally as we have done for so long with land, commodities and labor. More than just a monetary revolution, it is thus an evolution of concepts that is brought to us by the blockchain and by the young entrepreneurs who conceived and implemented it44.

After having circled around the closed city of institutional and monetary Jericho seven times, will the walls of misunderstanding between the real economy and the didactic economy collapse? Will it be possible to rebuild the political economy not only for the sake and the wealth of nations, but also by taking into account the wealth of those global firms that contribute so significantly to improving the well-being of humanity, notwithstanding the trials they are the target of? This could be the beginning of a big upheaval which is announced by the disruption of uses and behaviors, promoted by technology at the digital era!

Bibliography

[BAL 16] BALDWIN R., The Great Convergence: IT and the New Globalization, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 2016.

[BOU 62] BOULDING K., A Reconstruction of Economics, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1962.

[CHA 80] CHAMOUX J.-P., L’information sans frontière, La Documentation française, Paris, 1980.

[FOU 66] FOURASTIÉ J., Idées majeures, Gonthier, Paris, 1966.

[JES 91] JESSUA C., Histoire de la théorie économique, PUF, Paris, 1991.

[NOR 81] NORA P., MINC A., Preface by D. Bell: The computerization of society, MIT Press, Cambridge 1981 [original French La Documentation française, Paris, 1978].

[OHL 17] OHLHAUSEN M., “Does the US Economy lack competition?”, Criterion, vol. 1, p. 47 sq., 2017.

[POT 18] POTTS J., DAVIDSON S., DE FILIPPI P., “Blockchains and the economic Institutions of Capitalism”, 2018, available at: http://www.academia.edu/33138299/Blockchains_and_the_economic_institutions_of_capitalism, 2018.

[RIS 30] RIST C., Cours d’économie politique, vol. 2, Sirey, Paris, 1930.

[ROB 22] ROBERTSON D.H., Money, Nisbet, Cambridge, 1922.

[SCH 42/46] SCHUMPETER J., Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, George Allen & Unwin, London, 1942 & 1946.

[SHA 17] SHAPIRO C., “Antitrust in a Time of Populism”, SSRN, 2017, available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3058345, 2017.

Conclusion written by Jean-Pierre CHAMOUX.