Chapter 10

Transforming from Practice to Business

Elite advisory firms distinguish themselves in many nuanced ways. But there appear to be three big areas in which the top-performing advisory firms (Leading Firms) have made the right decisions that helped them to truly stand out: human capital management, technology implementation, and profitable pricing.

These insights were revealed in “Mission Possible IV,” which Pershing commissioned the consulting firm FA Insight to research and write. FA Insight tracked the individual performance of advisory firms between 2008 and 2012, and then segmented the Leading Firms based on growth rate, profitability, and owner’s income as a percentage of revenue. The top-performing firms grew revenue at twice the rate of their peers!1

Each of the Leading Firms demonstrated a level of courage and confidence that was not apparent in the rest of the advisory population. Consider where we were as an economy and an industry in 2008 and how far so many firms fell in terms of assets under management, revenue, and profitability. While there were many advisors who believed this downdraft was an aberration and eventually the markets would reinvigorate their businesses, the Leading Firms in this study went a step further by actually investing ahead of the curve while also adopting better discipline around technology selection, profitability management, and people recruiting and retention.

One data point that reveals this newfound discipline is that for the Leading Firms in this study, their overhead costs (expense ratio excluding professional compensation) decreased to 36 percent of revenue. Meanwhile, the overhead expense ratio for all other independent advisory firms rose to 45 percent of revenue in 2012.2 A 9 percent variance is huge. For example, if your business generated $2 million in annual revenue, you would be spending $180,000 more on overhead than a comparable Leading Firm.

One consequence of better expense control is that the Leading Firms produced an operating profit of 29 percent in 2012 compared to 13 percent for the rest of the industry on average.3 For a $2 million practice, that variance means the Leading Firms had an operating profit of $580,000 compared to $260,000. What I like about this statistic is that it validates the argument that people are an asset on which to get a return and not just a cost to be managed. Clearly, the investment these firms made in human capital paid off.

When surveyed in 2009, almost half the advisory firms that have emerged as the Leaders said they intended to add head count and were not planning to lay anybody off. For the most part, they made good on this commitment with the median firm adding two more people for every half-time employee by the average firm.

This reveals a keen understanding by the Leading Firms as to what ultimately drives growth in the advisory business. The reality is that most advisors suffer from limited capacity, which makes it difficult to pursue or even take on more clients without materially altering the client experience or terminating existing clients. By investing in capacity before their growth occurred, these Leading Firms were in a better position to take advantage of market movements and the addition of new clients who had become alienated from their previous financial advisor during the downturn.

A subtle shift in who these firms hired also occurred. Instead of perpetuating the old approach of hiring other advisors or “rainmakers” who may or may not work out, these firms added so-called nonprofessional staff at a lower cost but with superior administrative skills so that their current team of business developers and advisors could become more productive and effective.

As an example, lead advisors have been able to increase the time they spend with clients to 75 percent compared to 52 percent for the average firm.4 This increased capacity frees them up to take in even more clients without affecting the experience. Furthermore, the revenue per professional in the Leading Firms is $150,000 greater than in the average firm.

It is no coincidence that these fast-growing firms also added professional management, which also freed up the advisors to focus on new business opportunities and existing clients while still executing on their business plan.

One area in which professional management contributed greatly to the Leading Firms was in how these firms deployed their technology. By realizing that what matters is not the number of tools used but rather the way in which technology is used, these professional managers introduced disciplined selection processes, emphasized training, and focused on improving workflow efficiencies. What is interesting is that while the Leading Firms showed better profitability and productivity numbers, they spent less of their revenue on technology than the average firm in the study.

In addition to leveraging technology to improve their business-to-client processes, the Leading Firms tended to use technology more effectively to monitor and troubleshoot service delivery. Nearly 70 percent of the Leading Firms use time-tracking, CRM, and project management software in their business today.

The other area of business discipline that professional managers brought to the Leading Firms was around pricing strategies. Obviously, 2008 and 2009 tested the mettle of all advisors, particularly with respect to their client relationships. Many firms discounted their fees, waived minimums, or avoided fee hikes because they were unsure of how their clients would react. Many were humbled by the market cataclysm and to a degree lost belief in what they were doing was adding value.

Once again demonstrating a contrarian’s courage, the Leading Firms decided not to compete on price but on value, recognizing that they truly earn their keep in the most difficult of times. In the spirit of calculated aggression, many moved toward premium pricing. By commanding a fair price for value, they not only showed confidence to their clients, but they were able to cull out those clients who did not perceive the advisory relationship was worth the price.

Leading Firms were most aggressive with larger clients with fees on $5 million portfolios being raised by 10 basis point on average, while the other firms in the study reduced their fees by 10 basis points on average for comparable clients. A roughly similar trend occurred on assets above $10 million.

In addition to raising fees on their largest clients, the Leading Firms also strictly imposed fee minimums. This helped avoid the perception that large clients were subsidizing smaller clients and ensured that the smaller clients were paying fair value for the advice they were getting. It also ensured that they were able to cover their costs of serving lower-value clients.

Business owners, just like investors, make calculated guesses every day with the hope of a better payoff. In the case of the Leading Advisory firms, they clearly made decisions informed by the facts and were not swayed by emotions. They positioned themselves well for a strong market upswing, and to capitalize on the new business opportunities that would eventually come their way.

They have blazed the path for others who may be more timid about their growth strategies. Obviously, the Leading Firms made choices when the world was in a trough. Much has changed since the Great Recession began, but the argument for hiring ahead of the curve, deploying technology more intelligently, and maintaining pricing discipline still makes sense for growth-minded advisory firms.

But Are You Scalable?

Common wisdom holds that the advice business is not scalable. While operating leverage may be easier to attain in other industries, such as manufacturing or software development, advisory firms can achieve scale once they reach a certain level of critical mass.

Investopedia defines a scalable company as one that can “improve profit margins while sales volume increases.”5 Does that description apply to advisory firms?

The 2014 Financial Performance Study of Advisory Firms conducted by Investment News and sponsored by Pershing Advisor

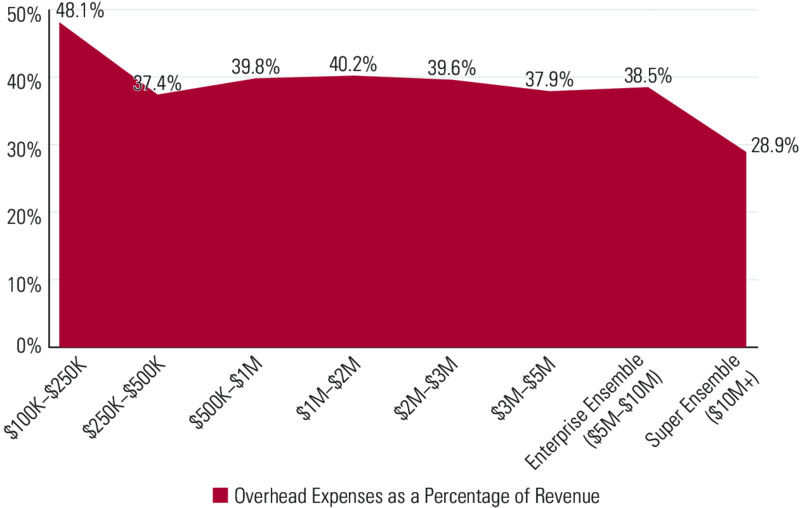

Solutions revealed that many growing advisory businesses are seeing margins improve as revenues increase (see Figure 10.1). For example, overhead expenses as a percentage of revenue dropped from a high of 48.1 percent to 28.9 percent as advisory firms broke through certain revenue and asset barriers.6

Figure 10.1 Crtical Mass

Source: 2014 Investment News Financial Performance Study of Advisory Firms

The most precipitous decline in the expense ratio was noted when advisory firms became “Super Ensembles,” defined as an advisory business with at least $10 billion in assets under management (AUM) and at least $10 million in annual revenue (see graphic).

For the average independent firm, these numbers may seem daunting, but $10 billion of AUM is not beyond the reach of the next generation of financial advisors. Not only does the expense ratio decline as a firm gets bigger, but revenue growth also accelerates with size. Why? Because a larger market presence creates increased efficiency, stronger discipline around business development, and the ability to build a brand.

The number of Super Ensemble firms today proves that the business of financial advice is going through profound change. When Mark started benchmarking the profession in the late 1980s, many advisors hoped to get to $100 million of AUM. At the beginning of this decade, the new Holy Grail was $1 billion. Now, the many firms breaking through the $5 billion mark and even the $10 billion mark reveal a transformation that few could imagine when the independent advisory movement took root.

Yet most advisory firms are small businesses that suffer the same strains as any closely held enterprise. The Small Business Administration defines a small business operating in the service sector as a company with revenues no greater than $21.5 million.7

The consolidators like Focus Financial and United Capital are capitalizing on the travails of running a small business by bringing like-minded firms together under one company, and new model firms such as Hightower are creating national advisory brands using broker-dealer command-and-control structures while delivering an advisory experience. But sizable owner-operated enterprises like Silvercrest, Aspiriant, Oxford Financial Group, and Tolleson have redefined the way advisory firms look and feel by growing strategically and organically, and not necessarily through aggressive recruitment or acquisition models, though tuck-in mergers may have rounded out some of their growth.

The achievement of scale provides a clear economic advantage to advisory firms. It enables such businesses to be more effective at the recruitment and development of talent without straining the income statement, it helps them to create critical redundancies, and it allows them to compete on price in cases when that is important.

There are risks to growth, however. The pursuit of critical mass can also contribute to cultural dysfunction, defection of employees, and impaired quality control. The more the principals in a firm are removed from the daily activities and supervision of specific client engagement, the greater the risk that steps may be neglected, recommendations may be inappropriate, and errors may be made.

To protect against self-destruction brought on by growth, advisors must view scale not as a natural byproduct of growth, but as something that occurs only when the leadership is thoughtful about the business they wish to create, systematic in the processes they implement to manage growth, and aware of the metrics that indicate when their train is going off the rails.

Advisors must focus on the following key areas if they hope to achieve scale:

- Expansion into new locations

- Examination of workflow and processes

- Recruitment, retention, and development of people

- Constant monitoring and measuring of critical ratios

We cite expansion into new locations first because this seems to be the way in which advisors believe they can grow quickly—by merging in or acquiring another firm in a different city. The first question one should ask is whether the firm can achieve critical mass in the new location itself. Based on our experience, it appears that a reasonable level of operating efficiency occurs when an advisory firm generates in excess of 10 million of annual revenue (a proxy for staffing, assets, and clients in most cases). At this level, an advisory firm has sufficient redundancies and capacity to grow. When advisors open an office in a new location with no plans to get it to critical mass, they become vulnerable. The loss of a key client or key employee or partner in the remote location may force them to close up shop as quickly as they opened the doors.

Streamlining workflow and processes probably constitutes the easiest way to manage growth. Most advisory firms have been doing the same thing the same way since they began. When they reexamine their approach, they often discover many functions that are repeated over and over again and therefore could be automated or done by a lower-level associate in the firm. An improved workflow enables advisors to lower their cost of labor and increase their efficiency, both of which help to reduce operating expenses within the firm.

Talent retention and development may be the area of greatest risk. All businesses tend to lose some focus as new people join the firm. To counter this, firms must implement a conscious strategy around training and inculcating the values that leadership holds dear. Regular performance evaluations and meetings with new associates help to reinforce expectations. When the advisory firm opens a new location, the ability to transplant cultural values becomes an even greater challenge if a culture carrier is not deployed to the new office. A decision on whether to merge, acquire, or open a new location may hinge upon whether the firm has somebody willing to relocate to provide this necessary leadership.

As with any investment, it is important to define success and to measure performance against those metrics. Even more critical is the need to establish leading indicators for the firm in general as well as for all branch offices or divisions. In addition to tracking operating profit margin and gross profit margin, it is helpful to monitor other ratios such as clients-to-staff, revenue-per-staff, revenue-per-client, error rates, growth rates, and attrition rates.

It seems likely that the advisory profession will soon resemble the accounting profession, with a small number of national firms, a larger number of regional and local firms, and the smallest number of solo practitioners. While the advisory business in general is profitable, there comes a point in the life cycle of a firm when its owners have to commit to growing or to staying small. Those caught in the middle never achieve scale or operating efficiency because they are too big and too small at the same time.

Fortunately, current models of success demonstrate how larger enterprises can not only grow efficiently, but also serve their clients effectively.

Risky Business

Someday soon an advisor will have to declare bankruptcy because he or she will not be able to cover the losses incurred in a fraudulent third-party wire transfer or a money laundering scheme. We don’t know who and we don’t know where, but I’m absolutely certain that the attempts to defraud are challenging the way in which advisors are managing risk.

Sometimes this occurs because advisors mistakenly believe that their broker-dealer or custodian is responsible for preventing the fraud. While such firms play a role by providing surveillance and tripwires that stymie illegal transactions, the ultimate burden is with the advisor, particularly those who are serving in a fiduciary capacity. It is not a responsibility that advisors can abdicate.

Independent advisors who have been given discretion over client assets and who have power of attorney to move money on behalf of their clients are especially susceptible. Those associated with a broker-dealer have the capital protection that comes with this affiliation, though even that could be inadequate to cover the loss if their BD is a small, lightly capitalized business. RIA firms, on the other hand, have no capital requirements so any losses would be debited to their management fee account or they would be required to pay out of their own pocket for any losses their clients incur.

Readers may be wondering why an advisor is on the hook for a crime committed against their client by someone else? The principal reason is that they are the ones responsible for verifying whether the request to wire funds is legitimate, they are the ones who send the instructions to the broker-dealer or custodian to execute the wires, and they are the ones who are responsible for KYC—know your customer.

They are also the ones who get most exasperated when the broker-dealer or custodian (when they smell something fishy) slows up the wire request. The advisor often argues loudly and sometimes profanely that “the client said he needs the money, so just send it to him!” In many of these cases, the aggressive advisor claims he confirmed the request with the client when upon investigation of the fraud, the custodian finds out he did not—because he did not want to bother his client or he was too busy. The only thing less defensible than carelessness is dishonesty.

More often, the advisor is fearful of looking unresponsive and in some cases unsympathetic when the wire transfer takes more than a few hours, so they put pressure on the keeper of the assets to act with alacrity. Sometimes, advisors also get touchy when the custodian elects to contact the end client directly to reverify what the advisor said was legitimate.

The Setting

Every day, sophisticated criminals from Detroit to Dubrovnik are capturing personal information on your clients, including e-mail addresses, financial data, copies of previous correspondence, and copies of signatures and account numbers. They are on a relentless campaign to take your clients’ money.

Often they begin with an innocuous request to the advisor asking about the available cash in the account. In some clever cases, they will add the balance inquiry to a previous string of e-mails so it appears like ongoing correspondence between the client and advisor. In a typical “e-heist,” the fraudster sends an e-mail to the advisor requesting money be transferred to a third party. It is often colored with some type of inconvenience that suggests it is hard for the client to be contacted. This would typically be something like, “I’m at a funeral,” “I’m traveling where there’s no cell or Internet service,” or “I’ll be in meetings all day and need to get this done in order to complete an important transaction.”

Eager to demonstrate good service even when reacting from the golf course or the beach, the advisor or his staff responds by sending the Letter of Authorization (LOA), which is signed and returned. What the advisor or her staff may not realize is that while the e-mail address used by the perpetrator may be legitimate, it is also a hacked account to which the fraudster has direct access. Absent any protocols by the advisor, this is as easy as lifting a wallet from an open handbag.

When the fraudster returns the signed forms to the advisor, he in turn forwards it to the custodian or broker-dealer for processing. With this authorization on file, the custodian conducts some safety checks to see if there are any anomalies or inconsistencies, and then wires the money to a third party as instructed. Those funds are immediately rewired to a bank in Malaysia whose offices are already closed for the night so nobody working in such locations can stop the fast-moving money from going out again. Those funds are moved quickly from the foreign account in the form of a debit card or cash withdrawal and the money is gone forever.

The bad guys are master manipulators who can use different forms of layering to cover their tracks. For example, they will troll dating websites to recruit unsuspecting accomplices. These unfortunate and oftentimes lonely souls are commonly referred to as “mules” who in the course of the seduction give up their bank account information as part of their Internet relationship. The fraudster will create a story about why he can’t take the direct wire and will ask his new romantic interest to accept the deposit of $50,000 to her account, for example. He will then direct the unwitting accomplice to Western Union, to send $45,000 to him and keep $5,000 “for when we meet.” When contacted by law enforcement, the accomplice will honestly be oblivious to what just happened and explain she was only effecting this transfer at the request of her “boyfriend.”

The Response

Four things can help to stop frauds like this:

- Train your staff on the red flags.

- Check to see if there were recent changes to their profile records.

- Always use the phone numbers and e-mails on file to respond to requests.

- Always call to verbally verify the request.

There are some common clues that you are about to be hustled by a fraudster. For example, when a request for a third-party wire transfer is inconsistent with the client’s past activity, you need to confirm that the client is in the loop. You can also find clues in the content of the requests when there are spelling and grammatical errors, or the requests are too formal. The requests often contain an explanation of how the funds will be used, such as the purchase of furniture using funds in an IRA, or tuition payments when the client doesn’t have school-aged children. We saw one request for the purchase of commercial baking equipment, which if for no other reason, stirred the advisor’s curiosity to inquire directly with the client.

To set up the transaction, a fraudster will often send instructions earlier to have the phone number changed. This way, when the advisor or his staff calls to confirm, they may not realize they are actually talking to the thief and not the client.

Avoid responding directly to the e-mail or phone number they provide. They may make a subtle change in the e-mail address and set up a new account that the advisor directs the response to, beyond the view of the legitimate client. For example, they may remove a period between first and last names, or eliminate a letter in a long surname so it looks correct in a cursory review. They also will say they are unavailable at their home or office and direct the advisor to call an unfamiliar number. The advisor or her staff may not know the client’s voice so these tactics can work.

The advisor or his staff should always call the client on the numbers on file to confirm the request before sending out any forms. In the event the forms go out and are signed and returned, the advisor or staff member should compare the signature to other legitimate documents and look for other inconsistencies in the request. The job of confirmation is often left to an administrative person. As part of your training, they have to know that avoiding the call or ignoring the protocols is not excusable. In one example, a fraudster sent an e-mail saying he couldn’t talk because he had laryngitis. Believing that that was reasonable, the advisor’s assistant did not make the call and the client’s funds were gone in an instant.

Vigilance is the duty of everyone in financial services. But clients themselves can do more to protect their data and information from the evil eyes of conniving spies. The next area of added value for advisors may be education programs and lessons on encryption to ensure that clients get not only a return on their money, but a return of their money. That said, it’s rare that the investor is not made whole by the advisor, custodian, or broker-dealer. The question is whether those covering the losses have the financial wherewithal to withstand such pain.

The Price of Independence

Semantics are important. For example, when one refers to oneself as an independent advisor, does this mean he or she is an independent business owner; independent in the ability to select technology and platforms; independent in ideas and recommendations to clients; or independent from direct supervision?

The answer to this question becomes important as financial advisory firms become more complex and new opportunities for conflicts and confusion arise. Furthermore, with each new innovation and each new claim of fraud or malfeasance against financial professionals of all stripes, clients and regulators are demanding more transparency into all our business activity. The more there is a quid pro quo element to your professional relationships, the less one can hold oneself out as independent by any definition.

Holding oneself out as independent does not in itself connote a higher standing or a better business model, but it is often expressed in a self- righteous tone. So naturally it begs the question: “What do you mean by independence?”

Thus, our challenge: We are an industry that uses garbled language to convey images to less-informed consumers and so it becomes more difficult for them to tell the difference between a zebra and a horse. Is business ownership and governance your definition of independence? If yes, then at what point in your growth cycle and span of control do you no longer have independence? If you have multiple partners, each of whom has a say in business governance and policy, have you drifted away from the freedom to act according to your instincts or own ideas? Do you lose independence the bigger you become and the more shareholders you accumulate? It’s a bit like asking, “When does a boat become a ship?”

If you sell your firm, are you as free to conduct your business as you did when you were not owned by a passive investor? Are there consequences for not hitting your growth numbers and does this influence your behavior? If you become a division of a bank or an accounting firm, do you have the freedom to make decisions that make sense for your advisory business but which conflict with the policies or interests of your parent? If independence means freedom to use whichever vendor you want whenever you want, how in fact do you demonstrate that, and how do you communicate this value to your clients? For example, if you are in a referral program with your custodian, and they require that in return for the lead you must hold those assets with them and pay them a referral fee in perpetuity, are you selecting the custodian based on the client’s best interest or yours? How do you communicate to your client what limitations (or increased fees) this program may impose on their assets over the life of the relationship? And if you decide the custodian is no longer delivering on its promise of good service or high value—or is still a safe place to hold your assets—may you move your clients without consequences to them or you?

If they give you favorable pricing in return for your use of their proprietary mutual funds, ETFs, or cash sweep accounts when they make substantially more in the relationship with you, are you giving your clients access to the whole of the market as a proper fiduciary advisor? Or are you acting as a salesperson for their products? If they give you money for technology or some other business support at a ratio tied to the volume of business with you, are you free from conflict?

If independence means you are free to make investment recommendations or act with discretion, how does that affect your independence when your broker-dealer limits you to only those solutions in their proprietary managed account platform? If your firm requires that you use only the master limited partnerships sponsored by your own company, are you acting as a client advocate or product advocate? If you are dogmatic users of ETFs or index funds and unwilling to consider other investment vehicles, are you truly independent in your advice or tied to a specific type of product?

When was the last time you truly analyzed the relationship between your firm and its vendors? How do these relationships affect your firm’s independence? How does this trickle down to other decisions your firm makes?

An even bigger question is why do firms enter into agreements with others knowing that they will be giving up a portion of decision-making control? Is it due to budgetary concerns? Lack of resources? Miseducation? Unavailable internal resources? Industry pressure? What can we do to remove these barriers and allow growing firms access to technology, vendors, and products that do not create such conflicts?

As the definition of independence can be somewhat blurry, how do regulators like the SEC enforce disclosures of conflict of interest?

We’re sorry for asking so many questions, but there are compelling reasons to probe more deeply into the subject for advisors, custodians, and broker-dealers.

In particular, several issues have arisen lately that contribute to these blurred lines. The first is the push by many in the profession to have all people delivering financial solutions to act in a fiduciary capacity. The second is the Department of Labor’s insertion into this debate on behalf of all retirement accounts, including IRAs. The third is the advocacy by groups such as SIFMA, FSI, and FINRA to adopt a harmonized fiduciary standard that protects their constituents but may not be consistent with how RIA firms currently interpret the guidelines. The fourth is the rapid consolidation of the industry, the emergence of more corporate buyers, the expansion of the hybrid advisor movement, and other factors that scramble the distinction between a broker and an advisor.

Before these forces of change, life in financial services was much clearer to consumers, regulators, the media, and even other people in the profession. There was a time when a broker was different from an advisor, when “fee-based” and “fee-only” did not imply the same thing, and when advisory firms were all owner-operated. But since circumstances have changed, we need to rethink the language we use to describe what we do and the intent with which we do it.

The confluence of these issues makes the definition of independence a sentence constructed of only dangling participles. What does the adjective modify? Business model. Ownership. Advice. Choice.

Why Does the Definition of Independence Matter?

The business model under which one operates is supposed to clearly reflect what clients should expect of you. A broker has a different obligation to a client than an advisor, for example. If my body aches, I want to know if I should be going to a chiropractor or an orthopedist. If my vision is bad, I want to know if I am seeing an optometrist or an ophthalmologist. If I am seeking tax advice, I want to know if I am seeing a CPA or an enrolled agent. Who you are helps to convey to clients a clear idea of what you do and how you do it.

This is not to imply that one business model is superior to another, but if how we conduct our business is not obvious and transparent to the client, then the integrity of our profession takes yet another hit. The overuse of the word “independent” is a good example of a simple phrase that tends to confuse the masses.

Are You Conflict-Free?

One strong magnet for the advisory side of the business is that one becomes a professional buyer versus a professional seller. The implication is that when acting as a client advocate instead of a product advocate, you are able to clearly position yourself firmly on the side of your clients. Clearly, one of the most appealing position statements in financial services is to profess a freedom from conflicts of interest. However, positioning oneself as “conflict free” may be the most difficult to prove. Regulators are poised to raise the bar on the fiduciary standard even higher.

In particular, the U.S. Department of Labor’s (DOL) regulation of the retirement business will clamp down on advisors who seem to serve their own interests before the interests of their clients. The DOL’s emphasis on a fiduciary standard of care likely will apply to the general delivery of advice in all of its manifestations, not just retirement accounts.

Acting in a client’s best interests is always the proper stance. Can you imagine a doctor proclaiming disdain for the Hippocratic Oath, which requires physicians to swear by certain ethical standards? Yet how are these standards defined in the financial services arena? The DOL’s proposed guidelines identify an ethical tipping point in the payment of commissions to brokers who sell financial products.

The DOL seems to view the payment of commissions as self-dealing and conflicted, as advisors may be incented to trade to generate income. They believe that conflicts may be mitigated by contractual obligations that will create a higher standard of client care. Pressure on the industry is causing many to shift to an advisory, or as some broker-dealers term it, fee-based model to diminish the threat of self-dealing.

Registered Investment Advisors (RIAs) who are fiduciaries under the Investment Advisors Act, and probably already act as fiduciaries under ERISA, are thrilled to point out how their fee-only approach positions them as client advocates rather than product advocates. Consequently, they feel validated by the government’s efforts to control conflicts of interest in the professional management of retirement savings.

Many contend that “what’s good for the client is good for the profession” and assume that there is enough business to go around. However, before RIAs become too self-righteous about their business models, this community must examine its own conflicts.

If you accept dinner with a fund company or tickets to an event from a technology provider, does this create a conflict? If you accept a referral from your custodian in return for keeping the assets on their platform forever, are you acting in your client’s best interests—or your own? If you charge fees based on the amount of assets a client brings, are your interests truly aligned? If you talk your client out of paying down their mortgage and thus keeping more assets under your management, do you disclose how this benefits you?

One of the greatest conflicts we see in financial services occurs when the client pays a fee based on the value they bring instead of the value the professional offers. How does a person’s net worth dictate the amount they should pay? That is like a doctor charging by the pound. In this comparison, both professions would be equating size to complexity, and the amount accumulated (in dollars or pounds) to the effort needed to serve the client.

The entire financial services industry is in dire need of a reputational facelift, but the new regulations raise some important questions about how the business of financial advice will be conducted post implementation. It would be a mistake for RIAs to think that a new fiduciary standard for the management of retirement accounts will not influence their business, including the vehicles they use such as options and derivatives; differentiated fee-based pricing for equities, fixed income, and cash; or even actively managed mutual funds. If there is a massive shift to passive investment vehicles, will active managers provide enough thrust to lift the indices that the passive vehicles depend on?

More clarity is required but I see two separate government agencies with two different definitions of fiduciary standard: one being a rule and one being a guidance policy. This will create complexity for RIA firms including new compliance standards, new tests for managing certain assets, and perhaps new certifications and examinations to ensure the business is competent and compliant.

Up until 1998, with a short interruption imposed by the federal government, motorists were allowed to drive on Montana highways at the speed limit of their choice as long as it was reasonably prudent. As soon as they crossed into Idaho or Wyoming, they had to adhere to the 55- or 65-mph speed limit that governed drivers in those states. Montana said, “Use your judgment as to what’s reasonable and prudent.” The other states said, “By law, we will tell you what’s reasonable and prudent.”

In this comparison, Montana’s system represents the fiduciary standard under the SEC, while the standard under the DOL resembles Idaho’s law-based approach. How will you govern the fiduciary behavior inside your firm? Will the new standard cause you to change your strategy for going under the radar?

These questions are all academic at this point, as we don’t know how clients, advisors, and supporting organizations will adjust their ways of doing business for the long term. We can assume that the push for greater transparency, fewer conflicts of interest, and more complete disclosures will improve the behavior of those motivated purely by the sale of a product and instill more faith and confidence in this industry. We will also likely see an even broader shift to retainer fees, hourly charges, and other relationships that better align advisors with the value they deliver.