CHAPTER 3

The Show Must Go On

FOR HIS OLDER BROTHER NICKY'S birthday, Conrad purchased a rather unusual gift. Feeling Nicky had become too stuffy and set in his executive ways, Conrad contracted with Consumer Recreation Services (CRS) to stage a rather elaborate experience. No present needed unwrapping as Conrad simply handed his brother a CRS-furnished card, inviting Nicholas Van Orton to participate in “The Game.” Once he accepted the offer, Nicky found himself involved in a world all its own, with intriguing characters drawing him into seemingly life-threatening situations, curiously assimilated into his day-to-day routines. Every time he thought he had it figured out, a new twist emerged until the events finally spiraled into a fast-paced climax. To pull off “The Game,” CRS had to put on a well-orchestrated show. No company, not even Disney, has mastered such intricate experience orchestration—staging rich, compelling, integrated, engaging, and memorable events—as well as CRS, the fictional business depicted in the movie thriller The Game, starring Michael Douglas as Nicholas and Sean Penn as Conrad. But the day has arrived when this type of staging will form the bulk of real commercial activity.

How so? To quote a line from the Broadway musical Rent, “Real life's getting more like fiction each day.” Look around. So-called reality TV dominates the airwaves. The significance of this new genre of television programming lies in how it mirrors the vast array of experiences consumed in the marketplace. Consider the parallels: The Bachelor (e-Harmony, match.com), HGTV shows galore (home improvement and decorating), Fear Factor (extreme sports), The Amazing Race (adventure travel and ever-new forms of tourism), Iron Chef (cooking schools and foodie festivals), Man Versus Food (competitive eating), The Biggest Loser (fitness centers and diet programs), Extreme Makeover (cosmetic surgery), Nanny 911 (life coaching), and, of course, American Idol (karaoke, Guitar Hero, and American Idol auditions!). Watch old footage of game highlights from the National Basketball Association, and compare its matter-of-fact action to today's sport, with its colorfully decorated floors, lavish pregame light shows, and poster-boy personalities. The NBA first gave us Dennis Rodman. The NFL followed with “T.O.” and “OchoCinco,” bedfellows in the personification of real-life fiction, tweeting their day-to-day lives. All major sports leagues find their in-stadium events having to compete with the at-home viewing experiences enabled by new television technologies. Furthermore, streaming video now makes it possible to display every everyday event at ordinary places—from repair shops to maternity wards—on the World Wide Web, where they can be viewed by anyone anywhere in the world. (Perhaps real life is less like The Game than The Truman Show—the film in which Jim Carrey plays a real person who unknowingly lives in a made-for-TV world.)

Experience orchestration has become as much a part of doing business as product and process design. The evidence is everywhere. In restaurants and retail stores, classrooms and parking garages, hotels and hospitals, leading companies set the stage for others now joining the Experience Economy. No longer in the embryonic phase of development, pioneering experience staging has resulted in practices that provide the starting point from which still further refinements will surely emerge. Elvis has left the building, and it's showtime!

Theme the Experience

Just hear the name of any theme restaurant—Hard Rock Cafe, House of Blues, or the Medieval Times, to name a few—and you know what to expect when you enter. The proprietors have taken the first, crucial step toward staging an experience by envisioning a well-defined theme.1 A poorly conceived theme, on the other hand, gives customers nothing around which to organize their impressions, and the experience yields no lasting memory. An incoherent theme is like Gertrude Stein's Oakland, California: “There is no there there.”

Of course, such theming can take diversely clever forms. Darden Restaurants, the world's largest full-service restaurant company, operates a vast array of differently themed chains: Red Lobster, Olive Garden, Longhorn Steakhouse, Capital Grille, Bahama Breeze, and Seasons 52, each with its own distinctive design inspiration. The Darden restaurant brand Seasons 52, most notably, simply leverages the calendar as its theme. The chain offers a “seasonally inspired” menu that changes four times a year; it runs specials fifty-two times a year (unlike daily specials, weekly specials are more likely to encourage diners to later recommend a dish to family and friends), and desserts (“mini-indulgences”) contain only 365 (or so) calories. Independent fine-dining establishments often employ even more sophisticated theming. Chef Homaro Cantu's postmodern Moto Restaurant, located in the meatpacking and produce district of Chicago, offers themed platings and wine pairings, among other technology-driven gastronomic fare (for example, one literally eats the “edible paper” menu). Well-orchestrated themes do not exist in name only (as did old high school proms in the gym) but instead act as the dominant idea, organizing principle, or underlying concept for every element in the experience.

Retailers often offend this principle. They talk of “the shopping experience” but fail to create a theme that ties disparate merchandising presentations together into a cohesively and comprehensively staged way. Home appliance and electronics retailers, for example, show little thematic imagination. Row upon row of washers and dryers, and wall after wall of refrigerators, merely highlight the sameness of different companies' stores. Shouldn't there have been something distinctive about an establishment called Circuit City? (Its array of merchandise took its thematic footprint from headstones at a cemetery, adumbrating its eventual demise.)

One retailer in the forefront of leveraging the experience of shopping was Leonard Riggio. When the Barnes & Noble CEO began to expand the chain of bookstores into superstores, he hit on the simple theme of “theatres.” Riggio realized that people visited bookstores for much the same reason they go to the theatre: for the social experience.2 So he changed everything about the stores to express this theme: the architecture, the way salespeople acted, the decor and furnishings. And of course he added cafes as an “intermission” from mingling, browsing, and buying. With online bookseller Amazon.com now the dominant force in the industry, offering reader reviews and forwardable e-mail confirmations, yet more needs to be done to turn the bookstores (still merely selling goods) into true book-recommending and book-reading venues (selling experiences). The rise of e-readers only intensifies the need to invent yet new themes in physical space if bookstores wish to successfully compete.

Consider the history of Forum Shops in Las Vegas, a mall initially conceived by developer Sheldon Gordon (of Gordon Group Holdings) and developed along with Indianapolis-based real estate company Simon Property Group. Triggering the rise of retailing as a new revenue stream for Vegas resorts, the Forum Shops opened in 1992. The mall displays its distinctive theme—an ancient Roman marketplace—in every detail, fulfilling this motif through a panoply of architectural effects. These include marble floors, stark white pillars, “outdoor” cafes, living trees, flowing fountains, and even a painted blue sky with fluffy white clouds that shifts from day to night every hour. Every mall entrance and every storefront, no matter the brand, must conform to the overarching theme. One telling detail we think brings it all together: the channels lining both sides of the hallways, a few feet from the store entrances, as if the shopkeepers cleaned their stores every morning with water buckets and then threw out the water to make its way to the Adriatic Sea. The theme implies opulence, and after a 1997 phase II expansion doubled the mall's size, sales grew to more than $1,000 per square foot (versus less than $300 at a typical mall). A phase III expansion in 2004, which added a four-thousand-seat “Colosseum” for show performances as well as four spiral escalators, continues the theming tradition.

Walt Disney's idea for Disneyland grew out of his dissatisfaction with amusement parks—themeless collections of rides, games, and refreshments geared to the young. As he related to biographer Bob Thomas, “It all started when my daughters were very young, and I took them to amusement parks on Sunday. I sat on a bench eating peanuts and looking all around me. I said to myself, dammit, why can't there be a better place to take your children, where you can have fun together?”3 And from these first thoughts Disney conceived the original idea of Disneyland—in his words, “a cartoon that immerses the audience.” It developed into a cohesive orchestration of theme rides—such as the King Arthur Carousel, Peter Pan's Flight, and the Mark Twain paddleboat (each “like nothing you've ever seen in an amusement park before”).4 These rides operated within theme areas—such as Fantasyland and Frontierland—within the very first theme park anywhere in the world, what its first brochure called “a new experience in entertainment.”5 What was the overarching theme of the Disneyland experience? Disney's 1953 proposal to potential financial backers begins with a very simple and engaging theme and then goes on to elaborate the meaning of this theme in very real, and soon realized, terms:

The idea of Disneyland is a simple one. It will be a place for people to find happiness and knowledge.

It will be a place for parents and children to share pleasant times in one another's company: a place for teachers and pupils to discover greater ways of understanding and education. Here the older generation can recapture the nostalgia of days gone by, and the younger generation can savor the challenge of the future.6

“A place for people to find happiness and knowledge” conjured such a wonderful image that Disney quickly found financial backers. In less than two years the themed park opened to far more visitors than anyone had imagined.

As a model, consider an often-used theme in novels and films: crime doesn't pay. Three simple words say it all. Or consider the television tavern Cheers, “where everybody knows your name.” Companies that stage experiences must seek equally crisp thematic constructions. Of course, businesses wishing to impart very different experiences require very different themes. The Geek Squad serves as a powerfully simple and appropriately geeky name for the Minnesota-based computer support business. It might appear that, like many theme restaurants, the Geek Squad's theme is stated right in its name. Not so. Rather, founder and Chief Inspector Robert Stephens says the organizing principle for everything the business strives to fulfill is “comedy with a straight face.”7 Using this theme allows “Special Agents” to maintain a straitlaced demeanor (as if they had walked off the screen of a modern-day episode of Dragnet) while engaging clients with Geek-based humor (as when flashing an identification badge: “Hi, I'm Special Agent Seventy-three here for your computer … Step away from the computer, ma'am”). They still perform the necessary installation or repair, but the costuming and props—white short-sleeve shirts, black clip-on ties, black pants, and company-issued shoes, VW beetles painted as black-and-white squad cars dubbed Geekmobiles—direct the enveloping geek performance.

The Geek Squad also provides a study in the difference between a theme and a motif. Dictionaries treat the two words nearly synonymously. Think of a motif, however, as the outward manifestation of a theme. The motif and theme can be one and the same (as is typically the case with Disney, when it explicitly uses movies or updated fairy tales as themes for its rides) but need not be. The Geek Squad's motif evidences itself in its name, logo, vehicles, badges, and attire; it all winks at the notion of law enforcement. But this motif is only the means through which the underlying theme tells a story. Indeed, at its best, theming means scripting a story that would seem incomplete without guests' engagement in the experience.8 As designer Randy White of White Hutchinson Leisure & Learning Group says, “Storyline-based themes are powerful. They draw guests into a fanciful, imaginary world and have the potential to touch the eye, mind and head of visitors.”9 Such theming can be scaled; in an otherwise mom-and-pop service industry, thanks to its 2002 purchase by Best Buy the Geek Squad has grown to more than twenty-four thousand agents in its “24-Hour Computer Support Task Force.” It did so by treating each customer interaction as an opportunity to (comically) tell the Geek Squad story (with a straight face). Any number of other highly fragmented service industries—car washes, dry cleaners, landscapers, nail salons, even funeral homes—represent opportunities to similarly build scalable businesses through theming.

Developing an appropriate theme for such experiences is certainly challenging. One place to start is with general categories of themes. In his insightful, albeit academic, book The Theming of America, sociology professor Mark Gottdiener identifies ten themes that often materialize in the “built environments” that he calls staged experiences: (1) status, (2) tropical paradise, (3) the Wild West, (4) classical civilization, (5) nostalgia, (6) Arabian fantasy, (7) urban motif, (8) fortress architecture and surveillance, (9) modernism and progress, and (10) representations of the unrepresentable (such as the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall).10 Marketing professors Bernd Schmitt and Alex Simonson, in their instructive book Marketing Aesthetics, offer nine more “domains” in which themes can be found: (1) history, (2) religion, (3) fashion, (4) politics, (5) psychology, (6) philosophy, (7) the physical world, (8) popular culture, and (9) the arts.11

Of course, these general categories only point out possible directions for discovering a specific theme. The Library Hotel in New York City, for example, took as its theme another classification system (and a set of domains far exceeding Gottdiener's or Schmitt and Simonson's lists)—namely, the Dewey Decimal System. In this architecture of theming, the hotel organizes each of the ten guest room floors based on one of ten major Dewey Decimal System categories: Social Sciences, Languages, Math & Sciences, Technology, The Arts, Literature, History, General Knowledge, Philosophy, and Religion. Rooms on each floor break down each category into different topics, with corresponding room numbers. For example, the six rooms on the seventh floor (“The Arts”) are numbered 700.006 (Fashion design), 700.005 (Music), 700.004 (Photography), 700.003 (Performing arts), 700.002 (Paintings), and 700.001 (Architecture). Each guest room's bookshelf is stocked with its own collection of topic-specific books, a corresponding coffee table volume, and topic-inspired artwork.

Every experience has a theme. Whether or not themed intentionally, whether or not designed well, and whether or not executed thoroughly and rigorously, a theme always emerges. Discovering a suitable theme is central to experience design. No matter what list or category prompts the discovery, the key lies in determining what theme will actually prove to be compelling and captivating. Five principles are paramount in developing such a theme.

First, an engaging theme must alter a guest's sense of reality. Each of Gottdiener's themes alters a dimension of the human experience, be it temporal age, geographic location, environmental condition (familiar/foreign, risky/safe), social affiliation, or self-image. Creating a reality other than the everyday—for doing, learning, enjoying, and being—underlies any successful theme and is at the heart of establishing a sense of place.

Second, the richest venues possess themes that fully alter one's sense of reality by affecting the experience of space, matter, and time. Parking garages are a space we've all experienced. Typical parking lines occupy space in one dimension and serve only to identify a stall—usually when drivers pull in, more than when they return. Signs provide a two-dimensional view, helping one see where one has parked. The themed design of the Standard Parking garage at Chicago's O'Hare airport, however, offers a place to experience parking spots in full 3-D perspective. Indeed, the intent is to bring energy and motion into the process of locating one's car. As a result, returning guests do not waste time wandering around looking for their cars.

Time feels different for children (and more than a few parents) at Disneyland's revamped Tomorrowland, which seeks to alter one's sense of the future. The same altered sense of the future can be experienced in various B2B settings, such as through the parade of five- to fifteen-minute talks at a TED Conference, with its three-word theme: technology, entertainment, design. The Hard Rock Cafe attempts to manipulate the past, as do many museums and corporate briefing centers. In an interesting twist of the clock, The Little Gym (decorated in a primary color motif ) overcomes any risk of dissatisfaction with its gymnastics instruction for small children by theming time itself. Rather than present lessons as themeless repetitions of tumbling drills, climbing exercises, and other apparatus use, it themes each program (such as “Funny Bugs”) as well as each class (e.g., “Upside Down Week”); the aim is to hold gymnasts' interest week-to-week while essentially going over the same underlying routines. Google themes its very own logo on its home page based on events that happened on this particular date in history. And in Southern California, the Cerritos Public Library bills itself as “the world's first experience library,” employing the theme of “journey through time” to alter the décor and furnishings of each room. In a town of fifty thousand residents, the library averages more than three thousand visitors daily.

Likewise, matter can be neither slighted nor ignored in the formation of a compelling theme. Themes may suggest alternative sizes, shapes, and substances of things. Cabela's and rival Bass Pro Shops' outdoor themes display the objects of an outdoor enthusiast's desire, through taxidermy and other backdrops, and in the process bring the hunter closer to the hunted. Marriott Vacation Club International places a large pirate ship, complete with water-firing cannons and waterslide planks, in its resort pool at its Horizons resort in Orlando. It supports the pirate motif and the underlying theme of “stuff in pool” by offering all sorts of things that work together to enhance the family experience, from “Captain Horizon” leading squirt-gun fights on the hour to VIP welcome packages placed in rooms as treasure chests. In a more adult setting, Marriott's joint venture with Ian Schrager, the new Edition “lifestyle” hotels, opened its first venue in late 2010 in Waikiki Beach. The resort includes an outdoor movie theatre, surfing and swimwear “boot camps,” and a hidden lobby bar accessible to guests only through a secret passageway.

And space matters. Billion-dollar airlines typically take few steps to alter the sensation of crammed space experienced by the coach traveler. Mike Vance, creativity expert and former dean of Disney University, relates in speeches how he travels with personal items in a bag he calls his “Kitchen of the Mind”—family pictures, pieces of paper, and assorted knickknacks that he uses to decorate his seat back, tray table, and window shade, especially on long flights. Flight attendants look at Vance as if he, and not the themeless airline, has a problem.12 Thus travelers welcomed the arrival of Virgin America to the United States, with its mood lighting and entertainment system that create a foreign feel for its version of domestic U.S. air travel. One feature that should not be overlooked is its contribution to this radically designed cabin space: the wall that hides the flight attendant jump seats and food prep areas has been eliminated, placing flight attendants in full view throughout the entire flight. As a result, the dynamic between passengers and crew has been vastly improved, largely because the crew now must act onstage, all the time, as a unified ensemble.

Third, engaging themes integrate space, matter, and time into a cohesive, realistic whole. To see how, consider a work of theology. In his apologetic for the Christian faith, Henry M. Morris states, “It is not that the universe is a triad of three distinct entities [time, space, and matter] which, when added together, comprise the whole. Rather each of the three is itself the whole, and the universe is a true trinity, not a triad. Space is infinite and time is endless, and everywhere throughout space and time events happen, processes function, phenomena exist. The tri-universe is remarkably analogous to the nature of its Creator.”13

Therein lies the power of storytelling and other narratives as a vehicle to script themes. Great books and good movies engage their audiences when they create completely new realities, altering every detail of the reading and cinematic experience. Lori's Diner, a small chain of restaurants in San Francisco, creates an authentic-looking 1950s diner, complete with vintage jukeboxes, pinball machines, booths, waiter and waitress uniforms—occasionally even a Fonz-like character outside who beckons passersby to enter into this past world.14 So why not borrow this principle for bank branches and car-rental shuttle buses, conference sessions, and other B2B marketing events?

Fourth, creating multiple places within a place strengthens themes. At the now-defunct Discovery Zone, almost every corner of the place was visible from any other vantage point. See-through nets separated one section from another, with the so-called ball pit attraction often at the center of activity. Even if this setting was meant to help parents keep track of their youngsters' whereabouts, it called to mind Gottdiener's fortress architecture and surveillance theme more than a place for imaginative exploration and play. Consider instead the American Girl Place. The merchandise is secondary to the overall experience, which is wonderfully staged by offering multiple places within the place. A visit starts with the library, where all the books written about each doll are displayed. A dozen or more animated screens display each doll's character. The restaurant, simply called “Cafe,” provides yet another place, and its doors remain closed until the appointed seating times for brunch, lunch, afternoon tea, and dinner. A photo studio provides a place for girls to have their pictures taken for customized covers of American Girl magazine. The studio comes complete with a separate area to receive a preparatory make-up session. Then there is the hair salon, where girls can have their dolls' hair styled or, for older dolls, restored to its original condition.

Finally, a theme should fit the character of the enterprise staging the experience. In 1947 Chicago developer Arthur Rubloff coined the three-word phrase “Chicago's Magnificent Mile” to describe the famous stretch of commercial property along greater North Michigan Avenue in downtown Chicago. It is a magnificently constructed theme, enduring for generations because it befits not only the walking that shoppers must do to shop and eat there, but also the luxury and opulence on display. Rubloff later formed The Greater North Michigan Avenue Association, which was instrumental in hosting “Cows on Parade” in 1999. Chicago was the first U.S. city to import this cow parade concept from Switzerland, commissioning local artists to paint three hundred life-sized cow statues that were placed throughout the city. The public art exhibit accounted for hundreds of millions of incremental tourist dollars as people flocked to Chicago to see and to be photographed with the cows. The cow theme was ideal, given Chicago's mid-nineteenth-century history as the only rail distribution hub for transporting livestock from the West to the rest of the nation. Other cities copied the themed exhibition, with mixed success (guitars in Cleveland, flying pigs in Cincinnati, and so forth) depending largely on how well the theme tied to the character of the city.

An effective theme must be concise and compelling. Too much detail clutters its effectiveness in serving as an organizing principle for staging the experience. The theme is not a corporate mission statement nor a marketing tagline. It needn't be publicly articulated—just as the term “Trinity” appears nowhere in the texts of Scripture—and yet its presence must be clearly felt. The theme must drive all the design elements and staged events of the experience toward a unified storyline that wholly captivates the customer. That is the essence of the theme; all the rest simply lends support.

Harmonize Impressions with Positive Cues

The theme forms the foundation of an experience, but you must render the experience with indelible impressions. Impressions are the “takeaways” of the experience—what you want customers to have topmost in their minds when they leave the experience. The congruent integration of a number of impressions affects the individual and thereby helps fulfill the theme. Thinking about impressions begins with asking yourself how you would like guests to describe the experience: “That made me feel …” or “That was …” Schmitt and Simonson again provide a useful list, this one delineating six “dimensions of overall impressions”:

- Time: Traditional, contemporary, or futuristic representations of the theme

- Space: City/country, East/West (to which we might add North/South), home/business, and indoor/outdoor representations

- Technology: Handmade/machine-made and natural/artificial representations

- Authenticity: Original or imitative representations

- Sophistication: Yielding refined/unrefined or luxurious/cheap representations

- Scale: Representing the theme as grand or small.15

Experience orchestrators can use these dimensions to think creatively about the many possibilities for rendering a theme with indelible impressions. The connection to space-matter-time is obvious.

Yet this list only begins to tap the relationship between impressions and the theme they support. For what may be the most comprehensive list of impressions imaginable, no source can exceed Peter Mark Roget's synopsis of categories. Roget's International Thesaurus (fourth edition) offers 1,042 categorized entries from “Existence” to “Religious Buildings” across 8 classes and 176 subclasses and, should you want the detail within the Thesaurus itself, 250,000 words and phrases.16 It's the richest possible source for exploring the exact words to denote the specific impressions you want guests to take away from the experience.

Words alone obviously are not enough to create the desired impressions. Companies must introduce cues that together affirm the nature of the desired experience for the guest. Cues are signals, found in the environment or in the behavior of workers, that create a set of impressions. Each cue must support the theme, and none should be inconsistent with it.

Joie de Vivre ( JDV) Hospitality of San Francisco employs a brilliant technique for harmonizing impressions with positive cues when it themes its portfolio of hotels, restaurants, and spas. Founder Chip Conley began his hospitality business by purchasing a cheap, rundown motel in the Tenderloin district of San Francisco. Conley wanted to create a unique hotel experience, but he didn't have the money—beyond that necessary to buy and remodel the property—to conduct market research to identify who might be attracted to the venue. So he seized on an industry that could provide such insights—magazines—and themed his Phoenix Hotel after Rolling Stone magazine. He pored over back issues to determine five impressions that the rock 'n' roll rag imparted to its readers: adventurous, hip, irreverent, funky, and young-at-heart. Conley then redesigned the entire place (much of it cosmetically and therefore inexpensively) to bring these impressions to life as a consistent, coherent, and compelling whole wrapped around the magazine theme. JDV turned the swimming pool into a “dive-in” for partying, colorfully decorated the guest rooms (including that little old place, room 3-2-1, as the “Love Shack”), and slapped bumper stickers from local rock bands on the housekeeping carts. “Listening posts” were set up for staff to pick up ideas from guests for additional cues that might enhance the experience. Note that JDV did not name the hotel after the magazine, advertise the connection, nor even tell guests the theme. Rather, it introduced cues to create the desired impressions, and, amazingly, without revealing its theme, the Phoenix Hotel became the happening place to stay in San Francisco for touring bands and their road crews. JDV Hospitality uses this same “pick a magazine” technique for each of its dozens of California venues.

Different kinds of experiences, of course, often rely on radically different kinds of impression-forming cues. At East Jefferson General Hospital in Metairie, Louisiana, just outside New Orleans, CEO Peter Betts (now retired) and his management team redesigned the hospital around the impressions of warmth, caring, and professionalism. The hospital conveys these three key impressions by means of having team members wear easily read name tags that list professional titles and degrees, and they knock before entering a patient's room, among other things. The hospital designates any area accessible to guests—including not only patients but also family members, clergy, and any other visitors—as onstage and all others as offstage. It then confines unpleasant activities (such as transporting blood) and “hall conversations” to offstage areas and carefully crafts all onstage areas with appropriate cues that enhance the experience. Toward this end, painted murals cover the ceilings of rehabilitation rooms where patients frequently exercise on their backs, and different kinds of flooring identify distinct locations (lobbies are carpeted, paths to dining areas are slate, and paths to conference rooms are terrazzo).17

Lewis Carbone, chief experience officer of Minneapolis-based Experience Engineering, developed a useful construct for engineering preference-creating experiences. Carbone divides cues—or “clues,” as he calls them—into “mechanics” and “humanics,” or what might be called the inanimate and the animate. The former are “the sights, smells, tastes, sounds, and textures generated by things, for example, landscaping, graphics, scents, recorded music, handrail surfaces, and so on. In contrast, 'humanics' clues emanate from people. They are engineered by defining and choreographing the desired behavior of employees involved in the customer encounter.”18

At Disney, to avoid any possible association with rowdy local carnivals or run-down amusement parks, management set the impression of cleanliness as a cardinal principle. The designers translated this concern into two key cues: the mechanics of making sure a trash receptacle is always within sight of any guest, and the humanics of assigning a large number of cast members whose sole role is to pick up any trash that does not make it into a receptacle. Well, not quite the sole role: they're also to make eye contact and smile whenever they're within ten feet of any guest to reinforce the “happiness” impression.

The cues trigger impressions that fulfill the theme in the customer's mind. An experience can be unpleasant merely because an architectural feature has been overlooked or underappreciated or is not coordinated with the overall theme. Unplanned or inconsistent visual and aural cues can leave a customer confused or lost. Have you ever been unsure of how to find your hotel room, even after the front-desk staff has provided detailed directions? Better, clearer cues along the way would have enhanced your experience.

Eliminate Negative Cues

Ensuring the integrity of the experience requires more than layering on positive cues. Experience stagers also must eliminate anything that detracts from fulfilling the theme. Guests at most constructed spaces—malls, offices, buildings, or airplanes—find them littered with meaningless or trivial messages. While customers sometimes do need instructions, too often service providers say it poorly or choose an inappropriate medium, such as the sign we encountered on a chair in a Wyndham Garden Hotel room some years ago: “For your comfort, this chair reclines.” (The better cue of having the chair reclined upon arrival would have rendered the signage unnecessary.) Cognitive psychologist and industrial design critic Donald Norman gives a “rule of thumb for spotting bad design: Look for posted instructions.”19 In other words, any instructional signage is a sign of poor design. It serves only to form a poor impression.

Seemingly minor cues can impair any experience. At most restaurants, for example, a host droning, “Your table is ready” cues customers to expect the usual meal service. That phrase is now so familiar it forms no impression. At a Rainforest Cafe, however, the host sets the stage for what lies ahead by proclaiming for all to hear, “The Smith party, your adventure is about to begin!” Should the Smith party fail to appear after the third call, the host informs the other guests that the Smith's “safari has left without them.” After we stated “Three, please” to a host at Ed Debevic's in Chicago, he snaked our party in and around tables until we finally inquired about our table. His smart-alecky response: “Oh, you didn't say anything about a table.” (Ed Debevic's harmonizes its cues around a set of impressions that can best be described as nasty, rude, mean spirited, obnoxious, and ill tempered; it works because of how well the company humorously harmonizes the cues. Our party should have picked up on the initial cue: our host sported a name tag bearing the stage name “Smiley.”)

To avoid giving cues at odds with its good-tempered themes, Disney cast members always act their parts, never stepping out of character while onstage. Only when offstage, in an area prohibited to customers, can cast members talk freely among themselves. Many historical villages, such as Old Sturbridge Village and Plimoth Plantation, both in Massachusetts, also require employees to stay in character (eighteenth-century farmers and the like at Sturbridge; Pilgrims and Indians at Plimoth). Others, such as Colonial Williamsburg and Jamestown in Virginia, significantly diminish the integrity of their experiences by allowing period-costumed employees to talk the talk of their present-day guests.

The idea of “role-appropriate” clothing and behavior can also apply to people with workaday jobs. At East Jefferson General Hospital, all team members must personify “the EJ Look”—a set of dress standards that eliminates potentially negative cues. Not allowed, for example, are casual shirts without ties on men, extra-long fingernails and certain shades of polish on women, and strong colognes or perfumes on either. The EJ Look helps the staff create the hospital's desired impression of professionalism and has proved so effective that people they meet out and about in the community often immediately identify them as being from East Jefferson.

Presenting too many cues, particularly when put together haphazardly—such as overservicing in the name of customer intimacy—can also ruin an experience. As a writer for Fortune put it in extolling the virtues of staying in chartered homes instead of hotels while traveling, “There are no check-ins, no checkouts, no bills to puzzle over, no inflated telephone charges (you dial direct and an itemized list of calls is sent to you later), and only a two- or three-night minimum. Even better, no service-industry intrusions: no bellman waiting to be acknowledged or tipped, no maids lurking in your room watching TV, no agents sneaking in at night to hide chocolates in the bed.”20 Lest they slowly lose their clientele to the better experience of an away-from-home home, hotel chains should work harder to eliminate negative cues: stop cluttering end tables, dressers, and desktops with tent cards and other service communication; assign offstage personnel to answer phones so that front-desk staff won't have to interrupt face-to-face conversations with paying guests to field telephone calls; make sure bellmen and maids perform their tasks unobtrusively; and so forth. Only then will their guests be made to feel truly at home.

Mix in Memorabilia

People have always purchased certain goods primarily for the memories they convey. Vacationers buy postcards to evoke treasured sights, golfers purchase shirts or caps with embroidered logos to recall particular courses or rounds, and teenagers collect T-shirts to remember rock concerts. They purchase such memorabilia as tangible artifacts of the experiences they want to remember.

Such items are often among people's most cherished possessions, worth far more to them than the manufacturing cost of the artifact. Take something as simple as a ticket stub, a natural by-product of many an experience. Perhaps you have some tucked away in the bottom of a jewelry box (with other valuable items), or your children have some carefully mounted and displayed in their bedrooms. Why do we keep these torn scraps of paper? It's because they represent a cherished experience. Your first Major League baseball game, a favorite musical, a meaningful date at the movies—all events that run the risk of fading away without a physical reminder.

Of course, that's not the only—perhaps not even the primary—reason we purchase memorabilia. Greater still may be our desire to show others what we have experienced to generate conversation and, not a small factor perhaps, envy.21 This factor provides more food for the thoughtful experience stager. As Bruno Giussani, European director of TED Conferences, related to us, “Memorabilia are a way to ‘socialize’ the experience, to transmit parts of it to others—and for companies entering the Experience Economy, they are means to entice new guests.”

People already spend tens of billions of dollars every year on this class of goods, which generally sells at price points far higher than those commanded by similar items that don't commemorate an experience locale or event. A Rolling Stones concertgoer will pay a large premium for an official T-shirt emblazoned with the date and city of the concert. That's because the price point functions less as an indicator of the cost of the goods than of the value the buyer attaches to remembering the experience. In addition to gaining a premium over run-of-the-mill T-shirts, the Hard Rock Cafe induces guests to make multiple purchases simply by printing the location of each particular cafe on its T-shirts.

Selling memorabilia associated with an experience provides one approach to extending an experience; giving away items inherently part of the experience is another. Mixing the memorabilia into the experience to be used by guests affords a richer opportunity to attach a memory to the physical artifact. Thus hotels print artwork on electronic key cards and design alternative slogans for “Do Not Disturb” signs. Some forgo text altogether, as the JW Marriott Desert Springs Resort & Spa has done; its door hanger is simply a pink flamingo with no text, harmonizing with the pink flamingos that grace the grounds. The Cafe restaurants in American Girl Place venues provide an exemplary illustration. Rolled napkins are placed inside hair scrunchies (colored black-and-white, either striped or polka-dotted, to harmonize with the room's décor). Once these perks are discovered, the young patrons immediately inquire as to whether they may keep them—only to be assured that the complimentary item is theirs to take home. (American Girl also sells memorabilia for its Cafe experience: dolls sit in twelve-inch-high chairs called “treat seats” during meals; they sell for $25!) Thomas Keller's French Laundry restaurant in Yountville, California, also mixes in napkin-holding memorabilia in the form of an embossed clothespin.

Companies should get creative and seek to develop wholly new forms of memorabilia. When the Ritz-Carlton in Naples, Florida, installed a new computerized safety system with key cards, management decided to give away the old doorknobs to past guests instead of selling or tossing them out. Each of the 463 knobs was engraved with the classic Ritz-Carlton lion and crown insignia, converted into a distinctive paperweight, and given to those guests—among the more than six thousand people who requested one—whose story of an experience at the Ritz most touched the hearts of the associates who read each appeal. The limited-supply doorknobs became a tangible reminder of a memorable stay, and, Ritz-Carlton certainly hoped, a cue to relive that experience in the future. The sense of obligation created within guests was worth far more than the Ritz would have gotten by selling the doorknobs.

Moreover, companies should develop memorable methods of mixing in the memorabilia so that the very means by which guests obtain the items becomes a signature moment, such as when young girls discover the hair scrunchie at the American Girl Place's Cafe. The City of Calgary does this in a remarkable way when it awards a tall, white Bailey cowboy hat to visiting meeting planners and speakers. Recipients raise their right hands when sworn in as “honorary Calgarians,” repeating an amusing oath (“I promise to wear my hat at all times … even when I sleep …”) before also receiving a certificate that bears an image of the hat as well as the date. Similarly, the Geek Squad pays attention to how agents bestow Geek Squad T-shirts on paying customers; they toss the shirts as a final act before zipping off to their next appointment.

With the proper stage setting, any business can mix memorabilia into its offerings. If service businesses such as banks, grocery stores, and insurance companies find no demand for memorabilia, it's because they do not offer anything anyone wants to remember. Should these businesses offer themed experiences layered with positive cues and devoid of negative ones, their guests will want and pay for memorabilia to commemorate their experiences. (If guests don't want to do this, it probably means the experience wasn't all that great.) If airlines truly were in the experience-staging business, more passengers would actually shop in those seat-pocket catalogs for mementos. Likewise, mortgage loans would inspire household keepsakes; grocery checkout lanes would stock souvenirs in lieu of nickel-and-dime impulse items; and perhaps even insurance policy certificates would be suitable for framing.

Engage the Five Senses

The sensory stimulants that accompany an experience should support and enhance its theme. The more effectively an experience engages the senses, the more memorable it will be. Smart shoe shine operators augment the smell of polish with crisp snaps of the cloth, scents and sounds that don't make the shoes any shinier but do make the experience more engaging. Savvy hair stylists shampoo and apply lotions not simply for styling reasons but because they add more tactile sensations to the patron's experience. Similarly, better grocers pipe bakery smells into the aisles, and some use sight and sound to simulate thunderstorms when misting their produce to better engage food shoppers. Indeed, in almost any situation the easiest way to sensorialize a service is to add taste sensations by serving food and drink.

West Point Market in Akron, Ohio, founded by Russ Vernon, was one of the first to serve specialty foods in a grocery store. Retail guru Leonard Berry of Texas A&M University describes this upscale market as “a sea of colors, an adventure in discovery, a store of temptation with its killer brownies, walnut nasties, and peanut-butter krazies.”22 Berry quotes Kaye Lowe, director of public relations, as saying, “We don't hesitate to let customers taste a product. Some people come in on a Saturday and eat their way around the store. Russ's favorite saying is: ‘Come see the sights, smell the delights, and taste the wonders of WPM.’”23

Services turn into engaging experiences when layered with sensory phenomena, as can be seen in the very earliest stages of life. Consider the task of feeding an infant. One evening during dinner, then eleven-month-old Evan Gilmore pushed aside his mother's hand, refusing the food she offered. So Daddy took over. In an act performed by countless parents before, the spoon no longer went directly from jar to mouth. Instead, it was taken two feet back and raised high in the air. With herky-jerky movements, the flying machine descended, accompanied by the sputtering motor-mouthed improvisations of Air Traffic Papa. Tightly clinched baby lips soon opened as wide as a hangar to receive a spoonful from each f light.

Believe it or not, this airplane game conveys the essence of what any dining establishment does to turn ordinary food service into a scintillating experience for paying adults: designing exactly the right sensations as cues that convey the theme for which the guests have come. With young Evan, everything fit the “flying food” theme and gave the impression that a safe landing was required. The experience stager eliminates negative cues (such as a sternly stated “Eat your food”), while tuning each positive cue (visually, aurally, tactilely, flavorfully, aromatically) to integrate the impressions into a believable and appealing theme.

To enhance its theme, the mist at the Rainforest Cafe appeals serially to all five senses. You first encounter it as a sound: sss-sss-zzz. Then you see the mist rising from the rocks and feel it, soft and cool, against your skin. Finally, you smell its tropical essence and taste (or imagine that you do) its freshness. It's impossible not to be affected by this one, simple, sensory-filled cue.

Some cues heighten an experience through a single sense by means of striking simplicity. The Cleveland Bicentennial Commission spent $4 million to illuminate eight automobile and railroad bridges over the Cuyahoga River near a nightspot area called The Flats. No one pays a toll to view or even cross these illuminated bridges, but the dramatically lighted structures are a prop that city managers now use to attract tourist dollars by making a nighttime trip to downtown Cleveland a more memorable experience.

Similarly, a single, simple sensation can completely detract from an experience. Think of the recorded or mechanical voices now heard everywhere—fronting voice mail systems, beginning a telemarketing pitch, guiding passengers in boarding and exiting shuttles, informing you of how to work a seat belt on an airplane, even giving you a wake-up call at a hotel. People quickly drown out this monotonous droning because companies don't bother to explore alternative creative ways of yielding the same benefits without the negative sensory cues. Here, the four realms of an experience presented in chapter 2 can be tapped to invent schemes to enrich the senses. How could an automated voice entertain—by using humor? How might it not only inform but also educate? How might it induce action to create an escapist experience? And how might the sounds of—or behind—the voice be so esthetically pleasing that guests just want to listen to it?

Adding sensory phenomena requires businesses to employ technicians who know how to affect our senses.24 Experience-based enterprises require architectural and musical skills not only to design buildings and select music but also to fill the experience with sensations that make sense. (In the future, hotels will provide “sensory specialists,” and not AV technicians, for meetings.) Not all sensations are good ones, and some combinations don't work. Barnes & Noble may have discovered that the aroma and taste of coffee go well with a freshly cracked book, but Duds 'n Suds went bust attempting to combine a coin-operated laundromat and a bar. Apparently, the smells of phosphates and hops aren't complementary.

Companies that want to stage compelling experiences should begin with all five principles outlined earlier to explore the possibilities that await them. They must determine the theme of the experience as well as the impressions that will convey that theme to guests. Many times, experience stagers develop a list of impressions they wish guests to take away and then think creatively about different themes and story lines that will bring the impressions together in one cohesive narrative. Then they winnow the impressions to a manageable number—only and exactly those that truly denote the cogent theme. Next, they focus on the animate and inanimate cues that could connote each impression, following the simple guidelines of accentuating the positive and eliminating the negative. They then must meticulously map out the effect each cue will have on the five senses—sight, sound, touch, taste, and smell—taking care not to overwhelm guests with too much sensory input. Finally, they add memorabilia to the total mix, extending the experience in the customer's mind over time.

All five principles—and not only the first one—together constitute the act of theming, or better, THEME-ing:

- Theme the experience

- Harmonize impressions with positive cues

- Eliminate negative cues

- Mix in memorabilia

- Engage the five senses

Of course, embracing these principles remains, for now, an evolving art form. But those companies that figure out how to design experiences that are compelling, engaging, memorable—and rich—will be the ones that succeed in the Experience Economy.

You Are What You Charge For

The transition to an economy in which experiences fuel the engine of growth is undergoing many of the same changes encountered in the earlier transition from the Industrial to the Service Economy. This transition begins when companies give away experiences in order to sell existing offerings better, just as IBM and others initially gave away services in order to sell their goods. Service providers, consciously or not, recognize the value clients place on the experience, but rather than charge separately for it, they surround their core services with experiential effects. Most restaurants, for example, still charge for the food even though customers come in for the overall experience. This à la carte pricing reflects a lingering food service mindset: charging for the activity of making individual items. Prix fixe (or table d'hôte) pricing, on the other hand, explicitly charges for the dining experience, a practice on the rise. At Moto Restaurant, for example, diners pay $135 for ten courses or $195 for the Grand Moto Tour of twenty (plus) courses; wine progressions range from $45 to $95. American Girl Place's Cafe charges a flat fee of $19 to $26, including gratuity, for its dining experiences—the exact price depending on location and meal occasion.

Ultimately, a business defines itself by what it collects revenue for, and it collects revenue only for what it decides to charge for. You're not truly selling a particular economic offering unless you explicitly ask your customers to pay for that exact offering. For experiences, that means charging for the time customers spend with you, such as charging an admission fee. Appealing to a buyer's five senses, mixing in memorabilia, minding your impressions and cues, and theming may create a greater preference for your offering versus that of its commoditized competitors, but unless you explicitly charge customers for using it—not for owning it—in a place or event you control, your offering is not an economic experience. You may design the most engaging experience for your service offering or within your retail establishment, but unless you charge people specifically for watching or participating in the activities performed—just for entering your place, as do concert halls, theme parks, sports arenas, motion-based attractions, and other experience venues—you're not staging an economic experience.25

Even if you reject for now the idea of charging admission—out of fear, uncertainty, or doubt—it should still be your design criterion. Ask yourself, What would we do differently if we charged admission? This exercise will force you to discover which experience will engage guests in a more powerful way. Bottom line: your experience will never be worth an admission fee until you explore how to stop giving it away for free.

Think about a pure retailer that already borders on the experiential. The next time you go to a Brookstone, watch customers meander around the store and play with the latest high-tech devices. Many wouldn't dream of actually having most of these physical goods at home or in the office. But notice how many enjoy playing with the gee-whiz gadgets, listening to miniaturized hi-fi equipment, sitting and lying on massage chairs and tables, and then leave without paying for what they valued—namely, the experience.26 Lacking admission fee revenue, one can only wonder whether the Brookstone chain will soon follow Sharper Image in selling only via catalogs and online.

Could such an establishment really charge admission? Today, few people would pay just to get into the store (or its website), although surely not enough (not, at least, as the company currently manages its stores) to sustain the enterprise on admission fees. But if Brookstone decided to charge an admission fee, it would force the company to stage better experiences to attract guests, especially on a repeat basis. The merchandise mix would need to change more regularly, perhaps daily, even hourly. Demonstrations, showcases, contests, and a plethora of other experiential attractions would add to the experience. Membership fees could provide access to trial use of new items or loaned “item-of-the month” merchandise. Indeed, it would no longer be another mere store but an escape from the reality of shopping elsewhere in the mall. As a result, the retailer might very well sell more goods.

Or consider Niketown. Its original design was steeped in such experiential elements as exhibits that chronicled past shoe models, displayed Sports Illustrated magazine covers featuring athletes wearing Nikes, a usable half-court basketball floor, and video clips of everyday athletes viewed in an intimate theatre. Indeed, according to a company press release for the opening of the first Niketown in Chicago, that store was “built as a theater, where our consumers are the audience participating in the production.”27 Through these flagship stores Nike built its brand and stimulated buying at other non-Nike retail outlets, all the while maintaining that its own locations were meant to be noncompetitive with other retail channels.

If so, then why not explicitly charge people to enter Niketown? An admission fee would force the company to stage compelling events inside, such as letting guests actually use the basketball court, perhaps to go at it one-on-one with past NBA stars or to play a game of h-o-r-s-e against a WNBA player. Customized Nike T-shirts, commemorating the date and score of such events—complete with an action photo of the winning hoop—could be purchased afterward. There also could be interactive kiosks for educational and entertaining exploration of past athletic triumphs. We're convinced Nike could generate as much admission-based revenue per hour at Niketown as American Girl does at its venues. Instead, sans admission fees, the Nike stores have increasingly become houses of merchandise. Gone are the basketball courts, the educational videos, and other immersive experiences, and in their place, more rows of shoes and racks of apparel.

Granted, an admission fee would make it more difficult to lure first-time guests (“You mean I have to pay to get in there?”), but it would be easier to get them to come back. And there's another benefit of charging admission. For those experience stagers struggling to attract guests for return visits, such as eatertainment restaurants, the admission fee alters the buyer's evaluation of the value of the total offering. For when restaurants try to recover all the costs of staging an experience from the food alone, people quickly get used to accessing the experience for free and then begin to view the food as grossly overpriced. So why go back? With an admission fee, guests rightly perceive each offering they consume—goods, services, and experiences—as reasonably priced in its own right. The same principle applies to direct manufacturers, website operators, insurance agents, financial brokers, business-to-business marketers, and any other cueless business that wraps free experiences around costly goods or services. The demise of many retailers—Imaginarium, Just for Feet, The Nature Company, Oshman's, and Warner Bros., to name a few—testifies to the fate of those who neglect to consider charging admission, as do the struggles of yet additional retailers—FAO Schwarz, Eddie Bauer, Guitar Center, Linens 'n Things, and, of course, Disney itself.

Disney's initial foray into specialty retailing outside its primary properties disappointed. Other than the Disney videos playing in the background, its mall stores pretty much looked and felt like everyone else's mall stores, and the blame lay squarely on Disney's failure to charge admission. Because no one paid to get in the door, Disney provided a pedestrian shopping trip rather than a magical adventure. Even when Disney put concerted effort into the architecture and furnishings—such as at its store in midtown Manhattan, where on entering you seemed to have been transported, for a moment, to Walt Disney World itself—the experience giant never harmonized all the cues. The elevator, for example, appeared both inside and out to be an entrance into Snow White's castle, but once you boarded, you were exposed to blaring rock music that had nothing to do with the medieval surroundings. And everywhere you found costumed employees (here, they did not earn the term “cast members”) totally out of character, talking among themselves. Perhaps this was not Disney's intention. Perhaps it was merely poor execution. But that execution stemmed directly from the lack of an admission fee—even one reimbursable later for merchandise—and it certainly diminished the Disney brand by failing to live up to the company's high experiential expertise. Disney eventually got out of the retail store business, returning only when its licensee The Children's Place went bankrupt, and now is finally adding in such experiential elements as a “magic mirror” and store-opening ceremony.

Perhaps the right way to start charging admission is to do so for only a particular portion of a place, or for certain times in a place. Apple Retail Stores—where enthusiasts as well as prospects go to “Gather. Learn. Create.”—charge for certain times in the store with its One to One offering. With a $99 membership, customers not only get system setup and file transfer services, but also can book one-hour training sessions or two-hour “personal project” sessions with individual trainers. During every moment at an Apple store when these sessions are held—and Apple trainers hold a lot of them—a portion of the space and a certain amount of time generates experience-based revenue apart from the sale of goods and services.

At four fun-filled Jordan's Furniture locations across New England, the company stages myriad experiences (including audio-animatronic replicas of the third-generation owners, brothers Barry and Eliot Tatelman; a Bourbon-Street-theme Mardi Gras atmosphere; and an IMAX theatre). Jordon's, now owned by Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway, still gives these away, but at its Avon, Massachusetts, store it charges admission to the Motion Odyssey Machine, which takes audiences on a thrill ride simulating a roller coaster, a dune buggy, an out-of-control truck, and so forth, complete with wind and water effects. As Barry Tatelman often said, “There's no business that's not show business.”

In the full-fledged Experience Economy, we will see not only portions of retail stores but entire shopping malls charge admission before a person is allowed to set foot in a store.28 In fact, such shopping malls already exist. Disney's archrival Universal Studios, for example, charges admission (in the form of a parking fee) to CityWalk. But the Minnesota Renaissance Festival, the Gilroy Garlic Festival in California, the Kitchener-Waterloo Oktoberfest in Ontario, Canada, and a host of other seasonal festivals charge admission for what are really outdoor shopping malls. Consumers find these festivals to be worth the entrance fees, because their owners explicitly script distinctive experiences around particularly enticing themes and then stage a wealth of activities that captivate guests before, after, and while they shop.

At the Minnesota Renaissance Festival, for example, handsome knights and fair maidens greet visitors to the twenty-two-acre domain of King Henry and Queen Katherine outside Minneapolis, hand them a News of the Realm guide on simulated parchment, and invite them to enjoy the day's festivities. Throughout the day various merrymakers in Renaissance costume—magicians, jugglers, peddlers, singers, dance troupes, and even a pair of bumbling commoners known as Puke & Snot—frequently accost guests (many of whom also clothe themselves in period costume) with the express intent of ensuring that they, their companions, and everyone else within earshot have a wonderful time. Among the numerous categories of activities in which guests delight—and that could apply to any experience—are the following:

- Period demonstrations (armor making, glass blowing, bookbinding, and so forth)

- Crafts that guests perform themselves (brass rubbing, candle making, calligraphy)

- Games, contests, and other challenges for which prizes are awarded (archery, giant maze, Jacob's ladder)

- Human- and animal-powered (never electric) rides (elephants, ponies, cabriolet)

- Food (turkey legs, apple dumplings, Florentine ice)

- Drink (beer and wine but also—in an admitted concession to modern concessions—soda and coffee)

- Shows, ceremonies, parades, and various and sundry revelry (magicians, puppetry, jousts), some of which require an additional fee

Not to mention the hundreds of Renaissance-themed shops (make that shoppes), all selling handcrafted goods appropriate to the period, such as jewelry, pottery, glass, candles, musical instruments, toys, apparel, plants, perfumes, wall hangings, and sculptures, or services such as face painting, astrology readings, portraits, and caricatures. With nearly every guest leaving with one or more bags of goodies, the Renaissance Festival experience clearly siphons off shopping dollars that otherwise would be spent at traditional malls and other retail outlets.

Fortunately for their conventional competitors, the proprietors of such festivals do not hold them year-round … yet. The Minnesota Renaissance Festival, for example, opens its gates weekends and Labor Day from mid-August to the end of September. Because of its intensity and unusual nature, most people do not repeat this kind of experience often enough to make staging it every day worthwhile. However, with appropriately malleable grounds and facilities, consumers could be enticed over and over again if different experiences were rotated through the same place. Mid-America Festivals, the company that runs the Minnesota Renaissance Festival as well as similar endeavors in other states, added Halloween-theme experiences (Trail of Terror, Gargoyle Manor, and BooBash) at the same locale, as well as a Christmas-theme gourmet dinner and entertainment called the Fezziwig Feast. Shopping malls that wish to embrace the Experience Economy must learn how to stage revolving productions, just as theatres did long ago, that entice people to pay an admission fee again and again.

Do you think people would be crazy to pay for the experience of shopping at their local mall? Imagine the reaction if, decades ago—just after World War II, let's say, when the U.S. economy was booming, flush with returning GIs buying houses in the suburbs and filling their garages with new cars and their kitchens with the latest in household gadgets—you had told people that in the near future the typical family would pay someone else to change the oil in their car, make their kids' birthday cakes, clean their shirts, mow their lawn, or deliver a host of other now-commonplace services. No doubt they would have said you were insane! Or imagine going back hundreds of years and telling rural farmers that in the centuries hence the vast majority of people would no longer farm their own land, build their own houses, kill animals for their own meals, chop their own wood, or even make their own clothes or furniture. Again, you would have been thought crazy.

The history of all economic progress consists of charging a fee for what once was free. In the full-fledged Experience Economy, instead of relying purely on our own wherewithal to experience the new and wondrous—as has been done for ages—we increasingly pay companies to stage experiences for us, just as we pay companies for services we once delivered ourselves, goods we once made ourselves, and commodities we once extracted ourselves. We find ourselves paying to spend more and more time in various places or events.

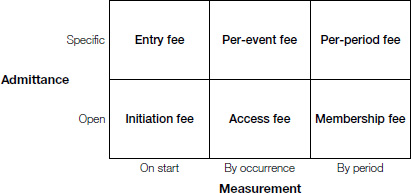

Admission to such experiences need not be limited to paying to enter, although such entry fees will certainly continue as one form of admission fee. In addition to paying at the start of experiences, customers may pay by occurrence or per period of time. And for each measurement (at start, by occurrence, and per period), paying guests may be admitted either for specific occasions or on an open basis. As shown in figure 3-1, six forms of admission therefore are available to experience stagers:

- Entry fee: Payment to enter a venue or event, such as going to a movie, seeing a stage performance, attending a sporting event, or walking a trade show floor

- Per-event fee: Payment to participate in an event, such as playing an arcade game, placing a wager, taking part in a competitive contest, or partaking in a conference or seminar

- Per-period fee: Payment for a set time—per minute, per hour, per day, per week, per month, per quarter, per year—at, for, in, or with offerings, such as satellite TV, Internet use, or club or association dues

- Initiation fee: Initial payment to affiliate with an experience, such as joining a country club, social club, website, or social network

- Access fee: Payment to obtain entrance, participation, time, affiliation, or membership, such as a backstage pass, beginner fee, test period, “professional seat license,” or trial membership

- Membership fee: Payment to be enrolled or included in a group's experiences, such as in a club, league, forum, co-op, or other association, whether for a group or an individual

Entry fees are paid before an experience just to get in; per-event fees are paid during an experience (or at the end of it) to get involved; and per-period fees are paid over time to yet again experience an offering. Initiation fees are paid to join and be received; access fees are paid to pass through and experience an exclusive offering; and membership fees are paid to continue and belong.

Remember: you are what you charge for. Knowing these varied admission fee possibilities opens up new opportunities for differently structuring economic relationships with customers—and thus alters the perceived value of one's offerings. For example, hotels that require guests to check out by a certain time in the morning still embrace a service mindset evidenced in the form of a room rate, wherein customers essentially pay for a collection of activities performed directly or (often) indirectly on their behalf. The requirement often frustrates guests. Hotels can shift to an experience mindset by charging per-period in the form of a day rate, allowing guests to stay in full twenty-four intervals before checking out. (Or alternatively, charge hour rates, as “hotel cabin” chains like YO! Company's YOtel now do.) Any business can differentiate itself by considering alternative approaches; any number of the six forms of admission could be combined to effect greater loyalty.

Charging explicitly for experiences, versus merely for goods and services, can lead to fundamentally altering the financial winners in an industry. Think movies. Blockbuster once dominated the movie rental industry, charging for each film rented, and fining customers (yes, fining customers!) for late returns. Enter Netflix. It offered an alternative pricing model, one based on charging explicitly for movie-viewing experiences (not movie-renting services). Netflix customers simply pay a monthly (per-period) fee, with unlimited movie rentals subsumed within the offering. Granted, Netflix also reinvented the underlying delivery service and is eagerly reinventing it again. Why? It's because by charging for time (each month) and not for the service (each rental), Netflix treats new technological platforms not as a threat to service revenues but as the means to lower delivery costs supporting its experience revenues.

Consider other such per-period possibilities. Imagine paying a company an annual fee to carefully manage an ever-changing mix of toys as part of a child development offering—instead of family and friends showering children with too many (inevitably unused) toys. Imagine a similar wardrobe management offering for adults, routinely providing expertise in the selection, maintenance, and replacement of garments—instead of closets packed with too many seldom-worn articles of clothing. Such subscription-based wardrobes could be customized based on color analysis, individual levels of fashion consciousness, and actual wear and tear. Or think about grocery stores, which charge for individual packaged goods and other foodstuffs. In a time when many people are overweight, couldn't a grocer offer to charge a per-period fee for a maximum number of calories to be taken home from the store each week? Almost any industry would benefit from seeking to differentiate based on for-fee experiences.

Charging admission does not necessarily mean, however, that companies stop selling their goods and services. (Still, some will indeed give away their lower-level offerings to better sell their high-margin experiences, just as telephone companies today give away cell phones to consumers who sign up for their wireless service.) The Walt Disney Company derives an awful lot of profit at its theme parks from photographic, food, and other services, as well as from all the goods it sells as memorabilia. But without the staged experiences (not only of the theme parks but also cartoons, movies, and TV shows) there would be nothing to remember—Disney would have no characters to exploit. While historically Disney started with the experience and then added lower-level offerings, the principle holds for those starting with goods and services that shift up to experiences. In the Experience Economy, experiences drive the economy and therefore generate much of the base demand for goods and services. So explore the experiences you could stage that would be so engaging that your current customers would actually pay admission and then pay extra for your services while they are so engaged, or pay more for your goods as memorabilia. In doing so, you would be following the lead of not only Disney but also the Minnesota Renaissance Festival, American Girl Places, prix fixe restaurants, and a host of other companies that have already entered the Experience Economy.

The same principle applies to business-to-business companies: staging experiences for their customers will drive demand for their current goods and services. The business equivalent of a shopping mall is, after all, a trade show—a place to find, learn about, and, if a need is met, purchase offerings. Trade show operators already charge admission (and could charge even more, if they staged better experiences); individual companies can do the same thing. If a company designs a worthwhile experience, customers will gladly pay the company to, essentially, sell to them.

Again, all the forms of admission fees are fair game for alternatively structuring B2B relationships. R&D-intensive companies could charge for membership and access to ongoing research findings and development intelligence. New experience-based revenue streams would emerge, replacing the paradigm of recovering costs only when a new good or service output eventually materializes. After all, new goods and services, once on the market, will only be reverse-engineered or otherwise copied and offered at a lower price. Charging admission to R&D may well provide the needed remedy for the tenuous cost issues causing turbulence (illegal imports, counterfeiting, medical tourism, and so forth) in the pharmaceutical, medical device, and other healthcare industries.

Will every company be able to charge admission? No, only those that properly set the stage by designing rich experiences that cross into all four realms: the entertainment, the educational, the escapist, and the esthetic. And only those that use the THEME-ing principles outlined earlier to create engaging, memorable encounters. Charging admission is the final step; first you must design an experience worth paying for.

But launching experiences worthy of charging admission is precisely what is needed in order to grow revenues, create jobs, increase wealth, and ensure continued economic prosperity now and in the future. Charging for goods and services is no longer enough. Instead of bombarding children with too many toys, we need new toy management and child development firms—operating essentially as the Netflix of toy-playing. Instead of closets and drawers full of too many clothes, we need wardrobe management offerings. We need new models for charging for nutritional foods. Fundamentally, we need to stop protecting old Mass Production businesses and start encouraging new customizing ventures. That show must go on.