CHAPTER EIGHT

The Art and Practice of Humility

The miracle is this—the more we share, the more we have.

—Leonard Nimoy

In writing about leader humility, my point is not to suggest that leaders should somehow be more dazzling or lenient. Humility does not require charisma or low standards. My intent is to showcase the extraordinary power of humility for working together, thereby creating thriving organizations and great results. There can be no doubt that Alan Mulally’s Working Together Management System (WTMS) did this at Boeing and Ford. Central to his approach is the unique role of the leader, and it is one based in humility.

You might be wondering whether it can work for you if your organization is smaller or if your leadership responsibilities are different or less complex. I believe it can, and I explain below how this approach can scale to different situations. Following that, I’ll share more about how humility looks in practice at the organizational level, beginning with a big-picture view of how Total Leaders (those with strong drive and humility) generate healthy, high-performing organizations—and concluding with examples of other organizational policies that support humility and performance.

Scaling for Smaller Size

The WTMS has a number of elements that generalize to organizations of any size. These include: (1) embracing the leader’s most important responsibility, (2) identifying the Creating Value Road Map, and (3) establishing behavioral norms for working together. A fourth element, the structure and process for how you oversee the work (ensuring implementation), can easily be adapted to varied circumstances. Let me discuss each of these in turn.

#1—Leader’s Responsibility

Mulally states that the leader’s most important contribution is to hold him- or herself and the team collectively responsible and accountable for defining a compelling vision, comprehensive strategy, and relentless implementation. You’ll recall that defining compelling vision and ethical strategies are two of the keys to leader humility. I have said that the leader creates the container, and Mulally clearly places responsibility on the leader to create the direction, processes, and culture that determine how we work together to deliver value for all stakeholders. He sees this as the “leader’s unique service.”

This most important contribution applies to leaders of any organizational size, not only to large organizations like Ford and Boeing. The leader’s unique role applies to entrepreneurial start-ups, midsized family businesses, the local neighborhood store, and community organizations. It also applies to leaders of skill functions like finance or human resources, and to those overseeing product divisions. And it applies to nonprofit and government organizations offering an extremely wide range of services, such as health care, education, or veterans’ services, to name just a few. It even applies to leaders who govern.

So, the number one issue in the success of WTMS and in scaling it to smaller or different types of organizations is understanding and accepting that the leader’s most important responsibility is creating and maintaining the container for work. When leaders understand how significant this is, they can be mindful and smart about the rest.

#2—Identifying Your Creating Value Road Map

Every organization exists to add value. Leaders need to guide the organization in identifying the best path to create value for all the organization’s stakeholders. Figure 9 showed a road map for creating value at Ford Motor Company. What if you are running an urgent-care clinic? Or a small copy and mailing center? Or a computer repair shop? You still create value and need to know what that is, who is affected, and what the best strategies are to create and manage results for all your stakeholders.

As one example, a couple starting a computer-repair shop might have an initial goal of providing repair services for customers. Quickly, they discover that they will need more technical staff and facilities to provide some requested services, along with administrative staff to conduct intake questions and process billing. They will need to decide exactly which services to provide and what their average turnaround time and pricing will be. Yet, if they step back and examine the broader context, they will likely notice competitors in the local market—not only for the same services, but for the talent they need to hire. They’ll see that there is also some risk of damage or data loss that requires insurance and legal advice. Cost-benefit analyses can help these leaders identify a path to profitability.

Looking even more closely, we see that the store’s reputation and success depend on the satisfaction of customers who give referrals and bring repeat business. Yet customers and the local community both are impacted by a challenging parking situation around the store. And perhaps some repairs require replacement components that are hard to secure and for which the store needs a reliable vendor. The leaders should recognize that stakeholders include not only employees but customers, community members, and vendors. Integrating all their needs should be considered in the Creating Value Road Map. This might lead to vision and strategy statements that reflect their path to creating value, such as “We provide quality repairs for customers at affordable prices and quick turnaround, and we validate their parking in a nearby garage. We offer strong wages and working conditions for our employees, and incentives to our vendors for being reliable.” The leaders and team can then create an appropriate work stream for implementing their vision and strategy and agree on performance goals and measures for achieving the desired results.

Importantly, measures need to address the interests of all stakeholders. This requires the keys of generous inclusion and developmental focus of humility. By assessing our impact on all stakeholders, we move beyond lip service. That is, we draw the boundary so that all who are affected by our work are on the inside; their needs and concerns must be actively incorporated in our vision, strategy, and measurement. In this example, the leaders should monitor costs and revenue, average turnaround time for repair, customer delight (with work quality, timeliness, and parking), vendor satisfaction, and community concerns about parking impact. Having a clear sense of how value is created and how to measure progress toward implementation is important—and doable—for organizations of any size.

#3—Establishing Behavioral Norms for Working Together

WTMS is explicit about Expected Behaviors. Many of these are specific interpersonal behaviors that are closely tied to the subject of this book: leader humility. And they illustrate how a leader’s use of the keys to humility—and the leader’s insistence that everyone else behave that way—generate a healthy culture for working together. This includes the keys to leader humility of balanced ego and integrity. “People first—love them up,” “Everyone is included,” “Respect, listen, help, and appreciate each other,” “Emotional resilience—trust the process,” “Propose a plan, and have a positive, find-a-way attitude,” and “Have fun—enjoy the journey and each other” are all behaviors that are based in leader humility because they show deep regard for the dignity of others. When these behaviors are modeled by the leader, and when others are expected to demonstrate these same behaviors, the organization becomes open, trusting, thriving. Importantly, these behaviors scale completely—they can be applied to any size organization.

#4—Structure and Process for Ensuring Implementation

Another set of the Expected Behaviors (figure 9) is what I consider practices for managing the work or overseeing implementation. Some of these I discussed in #1 and #2 above: how the leader’s acceptance of his or her most important responsibility as a leader, and then identifying the road map for creating value, can both be scaled to smaller organizations. That should result in a compelling vision, a comprehensive strategy, performance goals, and measures. WTMS also emphasizes having One Plan that everyone is working together on, where “Everyone knows the plan, the status, and the areas that need attention.” These scale very well to organizations of any size. The use of facts and data to assess progress should apply to organizations of any size because data refers to the key indicators that need to be monitored regularly to ensure successful implementation. Data can be quantitative or qualitative, and it can be gathered formally or informally, as appropriate.

Finally, we come to the structure for how leaders monitor implementation. Mulally’s Business Plan Review (BPR) is a weekly status meeting (with interim meetings to address concerns that arise), and the process of using color-coded slides to summarize progress ensures that everyone involved knows the plan, the status, and the areas that need special attention. The format and structure involved in the BPR for WTMS is a well-engineered practice. It is extremely effective at allowing the leader and team to maintain steady oversight of a very large, global, multiproduct organization with many stakeholders.

What if your organization has just five people? What if, instead of being spread out globally, you work together daily in an 800-square-foot office? Or perhaps you have fifty employees across two sites in the same city? Or five hundred people providing three different services? Perhaps you consider yourself midmarket in size with fifteen hundred employees. What structure is appropriate then?

In all cases, points #1, #2, and #3 above should apply well to your organization. You should still ensure that everyone knows the plan and its status. Also, you will need a way of monitoring progress that the team and you, as the leader, understand and follow to ensure implementation. But the structure for how you and they stay current can to be adapted to fit your work. There are many ways that can look, but here are some important questions to ask:

• How many people need to coordinate with you and each other? In general, larger staff means more communication nodes. It adds complexity that gets harder to oversee informally. Four to eight people can often interact very well informally; many organizations are of this size. Yet, as we approach ten to fifteen people, lapses in communication tend to occur, and this can hurt results.

• What is the physical proximity of this group? Are they all in one place or dispersed? Small teams who interact with each other daily because they are together can usually keep communications going well.

• How frequently do they naturally come in contact? Even if the team is small—if it’s composed of outside salespeople, for example—having offices in the same space doesn’t ensure needed information exchange.

• Where is the leader in physical relation to the entire team? And how often is the leader present with the team? Having a headquarters office while managing a remote branch puts the leader at risk of missing important information. And being away on frequent travel or out with clients 90 percent of the time differs from being present with the team half time every day.

• If the organization is small, what degree of overlap exists in team members’ jobs, and who among them needs what information to do their jobs well? A small organization may have five or ten people working on a common goal but with distinct responsibilities and very little overlap in what they do. Frequent meetings for status sharing will have less relevance in that type of situation than for a group of five or more who need to exchange and receive information to conduct their individual work effectively.

• What is the pace of change on the measures you are tracking? If you are concerned about sales in a brick-and-mortar retail store, you would not want to go a month before learning that sales were down year over year. Weekly or biweekly meetings are appropriate. If you lead a small, boutique consulting group, and securing government contracts takes a protracted period of time, significant change is not likely each week.

• What about the temperaments, motivation, personalities, and skill levels among your team? For skilled, highly motivated teams who exhibit the right behaviors when working together, depending on the leader’s needs as well, less oversight may be appropriate. For teams that struggle with each other, or where members are not well trained or very motivated, frequent interaction with the leader is important.

Creating a structure for overseeing implementation will be up to you, but recall that the leader’s most important responsibility includes holding self and team accountable not only for vision and strategy but for implementation. So, getting team input is recommended because it supports their dignity, and you should agree on the practice you will use to track implementation regularly.

At one end, there is the highly structured BPR that meets weekly. I recommend this for organizations that are moderate to large in size and complexity. For very small organizations, the questions above should help leaders determine what’s needed. A team of four or five people who interact continually in the same physical office, with the leader present as well, can typically communicate what it needs to know in real time. A separate structure (such as BPR) is generally not needed. Assuming that team members are skilled and fully engaged in the One Plan approach, and the norms of humility prevail, the organization can thrive on informality. This works well for many leaders of dynamic, small groups.

Other leaders prefer more structure. And organizations whose size and complexity are not so small (more than ten to twelve on the team) typically need a structured approach. Leaders and the group benefit from a regular meeting of staff to focus on specific implementation measures. WTMS provides a strong model for this. The questions above should help you decide what type of structure you need in order to manage implementation well.

Big Picture—Best Practices

Whether your organization is large, midsized, or small, the humility-based principles presented thus far create healthy containers for work. Let me now provide the big-picture overview of how leader humility creates thriving organizations and how the lack of leader humility can be toxic enough to produce harmful results.

Research has signaled for some time just how important leader humility is. Collins (2001) reported an in-depth comparison of organizations that became great (based on profits, stock performance, etc.) versus those that were merely good. The most important difference proved to be leadership. Intriguingly, while we might expect charisma to be important, it was humility that was found to be one of two differentiators of organizational performance. “Great” organizations had leaders who possessed both: fierce resolve for success and personal humility. Collins (2005) described this as “Level 5” leadership.

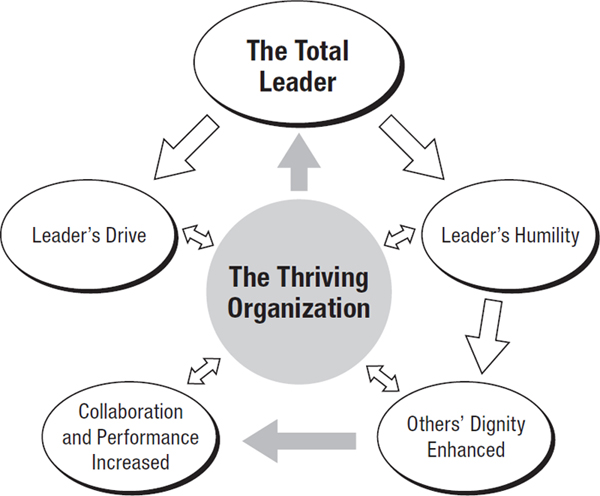

I am going to refer to leaders who combine strong drive with humility as the “Total Leader” because I’ll be distinguishing their impact from something that arises when humility is missing: toxicity. Drawing on his explanation of WTMS in chapter 7, let me use Alan Mulally as an example of a Total Leader to explain figure 11. His drive was focused on the whole organization: he used One Plan and weekly Business Plan Reviews to set direction and drive implementation. In addition, his genuine humility was evident. The Expected Behaviors he required of himself and his full leadership team (no exceptions) displayed deep regard for others’ dignity. As others’ dignity was supported, collaboration and performance increased, and organizations thrived under his leadership. As we should expect based on Collins (2001), the combination of strong drive and leader humility produced great results.

Because this has been true for all the CEOs I interviewed, you can see that humility is incredibly powerful. Much like a secret sauce, when coupled with drive, a leader’s humility builds a self-reinforcing system, as shown in figure 11. It enhances others’ dignity and collaboration and performance. Heightened enthusiasm and performance create a thriving dynamic in the organization, which provides positive feedback to the leader (appreciation and reputation), which in turn reinforces both the leader’s drive and humility.

But what happens when leaders are lacking in one of the elements that Collins (2001) found to be important? Well, if a leader has humility but lacks drive, the organization will tend not to advance well (which is bad for long-term performance). However, we tend to select leaders who are driven. We want them to be driven because we assume that their drive for results will lead to great performance. As a result, few senior leaders seem to lack drive. Instead, a much more common scenario is one in which leaders are driven—but lack humility. What happens then?

FIGURE 11. The Thriving Organization.

When leaders have strong drive that is not tempered by humility, very different organizational cultures—and different results—occur. Although there is certainly a range of these behaviors, from slight to moderate to extreme, figure 12 shows the direction of the effect of leader drive without humility on organizations. Many people describe leaders who are strongly lacking in humility, and the organizational cultures that result, as being “toxic.” Toxic leaders direct their drive at others—exhorting them to perform, primarily through power and control (sometimes through fear and intimidation).

The lack of leader humility triggers a downward spiral because it damages others’ dignity. Not being seen as individuals whose dignity matters, others feel used and disregarded. Lower morale and motivation result, causing leaders to drive others harder, sometimes berating them for not meeting goals. Mistrust rises, internal cross talk and complaining increases, and political behavior grows as people try to protect and defend themselves. Bystanders hear of complaints about leaders and learn to be on guard for mistreatment. These create such a toxic brew that organizational satisfaction and engagement decline, performance declines, and cynicism about leadership increases. The organization as a whole becomes toxic instead of high performing.

These models clarify why leader humility is so important for generating thriving organizations. Leader humility personally and directly affects the dignity of others, having an effect on engagement, performance, and satisfaction. When we recall from chapter 1 that Gallup (2018) found that 66 percent of employees are only minimally engaged cognitively and emotionally in their work, that they show up but do the minimum required, we need to examine the role of leaders in creating the container for working together. When the container is unhealthy, people may stay but they disengage. The same tendency occurs with other stakeholders: when the leader is toxic, when he or she lacks humility and disregards others’ dignity, many stakeholders will withdraw their support (partially or entirely). Working together is harmed and progress slows.

FIGURE 12. The Toxic Organization.

However, the humility of senior leaders can also influence the organization through the policies and practices they establish. In addition to WTMS, there are a number of other good practices that support dignity, some dealing with organizational vision and others tied to human resource policies around leader selection, development, compensation, and performance management. Although each organization needs to determine the policies that best fit its needs, I will share several humility-based best practices for you to consider.

Organizational Vision

Compelling vision and strategy are not only important keys to leader humility at the unit level but also a great starting point for humility-based policies and practices for the whole organization. As noted in chapter 5, Business Roundtable (2019) has reframed the purpose of business to focus on stakeholder value, not mere shareholder return. And Investopedia (2019) reported that investments are growing rapidly in organizations that are viewed favorably in their approach to environmental, social, and governance impact. Some organizations are broadening their visions accordingly; others need to do so.

Not only are the products, services, and competitive positioning important for investors and customers; organizations will not excel unless employees enjoy being there. What are we doing? What do we stand for? Is this something about which people can feel proud?

Many people have multiple choices about where they can work. If they take pride in the reputation of working for an organization, they will advance your reputation as well as contribute their best. When people look in the mirror, many also will question whether their work environment is adding positively to their reputation. Humility in leadership helps keep you on your toes so that they answer yes. If your organization is weak in this area, you should consider developing additional products, services, or contribution to the greater good that can improve your overall focus. If your products and services, and the way you conduct your business, are all wholesome, you have taken the first important step toward having a positive effect on people working there.

We are fortunate at Brooks Running because running is a positive force in people’s lives. I want people to work at Brooks because they opt into the values of our brand, our business, and how we do our work. —JIM WEBER

Leader Selection

A powerful set of policies and practices that are influenced by an organization’s leaders are those for selecting leadership talent. This begins at the board level because boards of directors select both the CEO and other board members. Data show that corporate boards tend to lack diversity in race and gender. In itself, this implies that board members are not practicing generous inclusion (an important aspect of humility) when they do not really see people who differ from the dominant model as being appropriate for invitation.

Homogeneous boards miss out on the value of having diverse views represented in their discussions. Diversity in the employee or customer base should be reflected at higher levels, including the board, to ensure that implications of strategic and competitive directions are thoroughly explored. Diverse membership also brings attention to people issues and inclusion, which are aspects of humility-based leadership. Consider this perspective from a CEO with substantial board experience:

Diversity definitely helps on boards. If I’m on a board and there’s another woman, the discussion is generally more comprehensive. Women tend to look at people and social issues—they’ll consider equity, and the diversity lens. The board table also becomes more inclusionary, collaborative. Women help connect the dots for the good of the whole. —PHYLLIS CAMPBELL

Boards of directors typically choose CEOs to lead the organization. So, if the board is inclusive and attentive to humility issues, we might expect it to value this in selecting CEOs. Also, practices in leader selection extend far beyond boards. The CEO and his or her leadership team also need to make humility an important factor in their choice of other leaders in the organization.

I’m always hiring for culture. It’s important that the people we hire can keep their egos in check, be good team leaders, and genuinely like people. It’s OK to be proud of your own accomplishments, but you’ve got to appreciate that others have accomplishments, too. Our culture is strong, such that if people came here selfishly for their own résumé, the organization would quickly sense that, and then chew them up and spit them out. —JIM WEBER

The CEOs I interviewed recognize that humility is not the only important factor in hiring leaders. But they generally placed it prominently in their considerations. Some saw humility as a factor that supported long-term growth in leadership:

When we hire executives, we tend to hire not just for today. We’re betting on that person for the next ten or more years. So, we want someone that is not only good today, but who will just get better over time. And we think humble people do this. Humility helps people develop faster, and they are more fun to be around. There are other qualities we look for also. We’re looking for folks who are smart and have the right kind of ambition—for the team and company as opposed to themselves. Finally, they need to be committed, we say “clipped in,” to our values. —BRAD TILDEN

Leader Development

Beyond leader selection, other policies and practices should address how organizations will develop future leaders. Three types of learning are especially important. The first is commonly recognized as a need to understand the business. Second, progress into advanced leadership typically benefits from external exposure that builds deeper knowledge in certain skills or broader knowledge of relevant industries and practices.

However, when it comes to leadership development, understanding the business and industry is not enough. An important third area of development is that of a leader’s social-emotional skills. This area of competence is too often neglected and can result in toxic organizations. As I have shown in the six keys to humility, the abilities involved in supporting others’ dignity are critical, and smart organizations consider this when developing leaders. It can be made explicit as part of succession planning and internal advancement too:

At Ford, and at Boeing, I always put a factor in our succession planning and performance management about humility. I actually used the word “humility.” Is this a person who seeks to understand before being understood? It was a significant factor in decisions for advancement. —ALAN MULALLY

The six keys to leader humility are very important, and most leaders can develop reasonable competence in each if motivated to do so. Nonetheless, nuanced judgment about when to use these keys and how to tailor them will be best when someone’s natural tendency is to feel and display deep regard for others’ dignity. If this tendency is seriously lacking, it may well pose problems over time because leaders face so many complex and challenging situations involving people. Wise CEOs take actions that prevent their cultures from becoming toxic:

[Thoughtfully] It’s very difficult to teach “people skills.” When we name managers, we have to feel pretty confident that they have good people skills. Certainly, we’ve made some mistakes. We like to think we’re developing a culture that’s “jerk free.” If someone hates his boss, you get turnover. We’ve seen some situations where we’ve turned people around, but if they are not responsive after a couple of tries, you need to move them to a job where they have less supervision of people. —JIM SINEGAL

Leadership coaching is one practice that can help develop people skills—if those receiving it are open to growth. The coaching can be informal (through mentoring) or more formal (hiring an outside coach). But part of coaching’s success will rest on the organization setting clear expectations that humility is important not only to leadership, but to success in the organization itself. Then leaders who are being coached will understand that humility is not merely a desirable quality but something they must develop as a fundamental leadership competency.

We’ve had situations where someone had the technical skills to succeed but needed improvement in humility to handle a senior position. You have to think through that very carefully because you want to balance opportunity for an individual with what’s best for everyone else—not just in terms of the skills to do a job but humility and skill in dealing with people. Humility is not the only factor, but it’s a very important one. And it’s important to be open and frank with a job candidate about the expectation for humility in how they interact with people. I have let people know that, if they fail on that part of the job, it will be career limiting. —JEFF MUSSER

Because it can be hard to teach people skills, the executives interviewed were mindful of this when discussing humility. Some take an assertive stance on this when developing leaders: in particular, they look for an individual’s self-awareness. If that is present, coaching and feedback hold much more promise as part of leader development.

People who don’t have insight into their behavior are very difficult to change. People who have humility are generally sensitive to how they interact with others. So, we select for it, and we also train for it, through feedback and coaching. We need people with self-awareness and humility who are open to criticism and guidance. If they lack that openness, they won’t be very successful in leadership. —JOHN NOSEWORTHY, MD

Progressive Compensation Approaches

There is wide recognition that income disparities have grown dramatically in the United States since the 1950s, when CEOs made twenty times the salary of the average worker. Forbes (Hembree 2018) reported that, for 2017, the multiple had grown so that CEOs made an average of nearly $14 million a year at an S&P Index firm, or 361 times the pay of rank-and-file workers. As the middle class has declined, a number of problems have ensued. Recognizing the dignity of workers, some organizations have used progressive approaches to compensation issues.

One of the more innovative approaches is that of Gravity Payments. In 2015, CEO Dan Price set the minimum salary for its employees in Seattle (an expensive city for housing, etc.) to $70,000 on hearing concerns that some employees were struggling to pay rent along with student loans. He believed that everyone deserved a living wage and slashed his own million-dollar pay package to pay for it. Having recently opened an office in Boise after acquiring the Idaho company ChargeItPro and finding that most employees there were making less than $30,000 per year, Price immediately granted those employees a $10,000 raise and promised to give annual increases that would ensure that everyone was making $70,000 by 2023 (Hahn 2019). Price was influenced to adopt this minimum income approach by a study that reported that additional money could foster significantly more happiness in the lives of people who made less than $70,000. Price’s decision clearly said “I see you” to his employees. Having cut his own pay to provide better wages for them is a form of generous inclusion—he showed deep regard for others’ dignity by sharing the wealth. Although he has drawn some criticism for his decision, his company fares well, and his workers report he has made a big difference in their lives.

Other approaches align bonuses and 401(k) contributions to organizational performance. In itself, this is not unusual. What is noteworthy is how the CEOs interviewed were intentional in aligning policies in ways that recognized the contributions of those who did the work and made sure the compensation approach supported their dignity. One of these is Expeditors International, known for strong growth and financial performance, as well as exceptional customer service in its industry. Employees are highly motivated by the way the company’s approach to compensation supports their dignity:

[A] sense of humility shows up in some of our policies. For example, we expect the CEO to pay for parking in the garage just like everyone else. And we give back 25 percent of pre-tax profit to the operating units. About 5 percent goes to cover regional costs, but 20 percent goes to bonus pay in each branch and is allocated to employees—the people who get the work done. Another example is a recent change to our 401(k) plan in which the company used to match $.50 per dollar on the first $3K. We considered going to $.50 per dollar on more—such as the first $6K. But we decided to go dollar for dollar on the first $3K because it would not disadvantage lower-level employees who can’t contribute as much. —JEFF MUSSER

A point worth noting in Musser’s example is the company’s attention to executive perks with the intent to minimize displays of status favoritism. Several other companies showed this too. Employees reported that Jim Sinegal did not have a reserved parking space. Howard Behar commented that, for many years, Starbucks’s policy did not offer company cars for executives. These are all examples of how organizational policies can create distance or suggest collaboration between workers and leaders.

The other point worth noting in Musser’s example is how carefully leaders need to think about all employees, whether part-time or full-time, when considering bonus and 401(k) arrangements. Taking this a step further, one of the CEOs interviewed described a thoughtful approach to compensation changes:

Early in my tenure at REI, we changed our incentive plan to include all employees—not just managers. Historically, REI had a generous contribution of up to 20 percent of salary to employee 401(k) plans for full-time employees, and an additional incentive plan for managers. But part-time staff, who comprised about half of the workforce, had no opportunity to participate. There was a disconnect for employees, especially part-timers, and we wanted to align their interests with those of REI.

So, we changed our practices to reflect a greater incentive for all full- and part-time employees to achieve our objectives. The 401(k) program was reshaped to guarantee participating employees 5 percent of their salary, plus an additional 10 percent tied to REI performance overall. We took the remaining 5 percent and funded a performance-based incentive plan for everyone, tied to a combination of their work group’s performance and the organization as a whole. That rewarded teamwork, giving all employees line of sight to what they could control, and allowed them to share in the company’s success.

This and other changes came by really listening to people—like what makes a living wage—and we began changing our practices to meet their concerns. It was personally humbling and enlightening to see the inconsistencies between our vision and practices. —SALLY JEWELL

In the retail sector, especially in quick-service food and beverage organizations, entry-level wages are low, and turnover is quite high. Starbucks is well known for having broken industry norms decades ago when it offered benefits to part-time workers. This made good strategic sense because it allowed the company to be more selective in hiring, and it reduced turnover. It also generated greater commitment to customer service in a company whose growth depended on that. This arose from people being treated with dignity—being seen as individuals who were important to the company and not as expendable workers.

Currently, a growing concern among employees is for policies that support parenting. Particularly in technology and professional service organizations, employees have wide professional choices and opt for organizations that offer parental leave. Leaders are showing humility in establishing policies that support families:

At TIAA, we strive for human-centered/employee-centered policies. In 2018, we implemented four months of paid leave for new parents. It’s for all employees, both full-time and part-time, regardless of their gender, whether or not they physically gave birth, and whether they will be the primary or the secondary caregiver of their child. It was expensive for us to do that, but we did it because we believe it was the right thing to do for our employees and their families. In financial services, your assets leave on the elevator every night. There’s a real war for talent out there. You need to show that you value people. —ROGER FERGUSON

Performance Management

A final area of policies and practices concerning leaders is how they are held accountable for performance. There are many ways organizations can do this, but serious attention needs to be given to humility-based behaviors to create a thriving culture. One approach is that of a trial period before a formal commitment is made:

When people are recruited to join the Mayo Clinic, they are given a three-year appointment. Part of that is to see if they fit, and they must be voted on for a permanent appointment. We are all in this for a higher purpose: to improve the health of patients. We look for humility as well as excellence and commitment. —JOHN NOSEWORTHY, MD

A final approach I will mention here involves tightly connecting leaders’ compensation to all significant organizational goals (not just some of them, as is commonly done). To illustrate how this can be done well, Alan Mulally used a Performance Management Process (PMP) as an adjunct to his Working Together Management System. PMP was designed to help leadership team members align their functional contributions and working-together behaviors with the WT system. Each team member would have his or her own plan for individual improvement, as well as responsibility to support other team members and the company’s One Plan. The organization’s compensation plan for leaders created a strong incentive to meet all those needs through the following formula:

Leader’s yearly bonus = Leader’s target bonus × company performance score × individual performance score

The leader’s target bonus is a percentage of the leader’s base salary and reflects his or her current responsibilities. The company performance score reflects the company’s collective performance on its One Plan. And the individual performance score reflects the person’s performance on both functional responsibilities and Expected Behaviors in the WT plan. This last element, the individual performance score, was formed by the leader and the team assessing together each leader’s individual performance score (that is, there is both peer and individual input).

Each element in the formula is rated from 0 to 2, with 2 being high. The multiplicative nature of the formula means that failure (a 0 rating) on any one element results in no bonus for the year. This system clearly holds leaders accountable for their performance—on Expected Behaviors as well as functional competence. In so doing, it ensures a culture of humility that supports peer collaboration and cascades down to others in the organization.

In sum, leaders’ direct behavior affects others’ dignity. And leaders’ indirect behavior influences others’ dignity through the policies and practices that leaders establish. Among the most important are those that affect the selection, development, compensation, and performance management of all leaders in the organization. Collectively, leadership teams implement policies that affect all others, creating thriving (or toxic) organizations.

![]() IDEAS FOR ACTION

IDEAS FOR ACTION

1. On a 5-point scale, with 1 meaning very weak and 5 being outstanding, evaluate your own performance on the leader’s most important contribution (holding self and team collectively responsible and accountable for generating compelling vision, comprehensive strategy, and relentless implementation).

2. Can you describe for everyone working with you how value is created in what you do? Do they understand who all of your stakeholders are?

3. Using a 5-point scale, rate your organization from 1 (toxic) to 5 (thriving).

4. Do you model the six keys to humility? Do you hold others in your work environment accountable for doing the same?

5. Consider the bullet points in the section “#4—Structure and Process for Ensuring Implementation.” What structure and process do you have in place to monitor implementation? Does it need to change? If so, how and why?