CHAPTER 2

Project Leadership: People Before Process

INTRODUCTION

Who will contribute the extra effort that pushes the team to a key milestone?

Who will take a risk on you because you are trustworthy and keep your promises?

Who will listen carefully to a different perspective and change their mind as a result?

Who will delay the project by failing to make a key decision?

Who will compromise on their requirements to meet the needs of another stakeholder?

These are the people on every project. The people who do the work, make decisions, contribute or withhold authority, ignore you or engage with you. But these people will not collaborate to deliver a project without the leadership of a project manager.

This chapter focuses on the primary job of a project manager: leading all the people who affect the project. Subsequent chapters in this book cover the science of project management, the tools and concepts that form the project management discipline. We emphasize leadership here, early in the book, so that each additional concept can be seen in the context of how it strengthens a project manager's ability to lead.

The need for leadership is not unique to projects, but there are some leadership challenges that are unique to the project environment. This chapter introduces two specific leadership challenges and provides guidance on how a project manager can choose to become a stronger leader. The themes of leadership introduced in this chapter will be carried on throughout this book.

THE PROJECT LEADERSHIP CHALLENGE

THE PROJECT LEADERSHIP CHALLENGE

Projects have two inherent characteristics that create a different kind of leadership challenge. First, projects create a change. That change requires a series of decisions, often made without full information. Think of a project then as a journey of discovery: We make assumptions, we make decisions, we take action, and we learn more. Then we repeat that pattern, over and over. The second characteristic that creates a challenge is that project leaders have very little authority over all the people who affect the project. Compare that to functional managers, whether they are department managers or CEOs, who usually have their responsibility match their span of control. Exploring these two factors in more detail is our starting point for shaping a vision of project leadership.

Chaos and a Journey of Discovery

Chaos was the law of nature; Order was the dream of man.

—Henry Adams

A kitchen remodel, development of a new video game, or installation of a fiber optic network are dramatically different project examples. One factor they all have in common is the need to make a series of decisions, from the first day to the last. Projects that use a predictive development approach, also called a waterfall approach, may seem more stable than adaptive projects that truly discover their direction at every step, but every type of project requires large and small decisions on a regular basis. Interpreting this reality as a journey of discovery means we embrace ambiguity and accept that acting without full information is both risky and necessary. (Chapter 4 discusses deeper comparisons of predictive and adaptive development methods.)

The many people on this journey—team members, executives, customers—need a facilitator and guide; someone who will focus them on the relevant decision in the context of the big picture with an appropriate sense of urgency. In contrast, a functional department has established procedures, and each performer can be an expert on their duties.

When Henry Adams wrote of chaos and order, he could have been describing the struggle of a project leader to create a unified plan of work that gives everyone a vision of the path to completion. The project management toolbox contains many techniques for creating this clarity, but these tools are wielded by people who look to the project manager for guidance. The chaos is not over when the plan is complete, either. The plan's assumptions will be both true and false. Politics, weather, and uncooperative technology are just a few of the interruptions that drive us off schedule or over budget. At each departure from the plan the people will turn to the project manager, not for an easy answer or a magical insight, but simply for guidance about how they'll reset direction. “We planned. We are off‐plan. How shall we respond?”

Over time, a project team can develop their own ability to respond, relying less and less on the project manager. Other stakeholders, though, such as customers, upper management, and suppliers, look to the project manager for direction, reassurance, and confidence. All the people on the journey of discovery need a leader.

Leading Without Authority

The second major challenge of leadership for project managers is their limited authority. They cannot direct stakeholders outside of their control; they must win their cooperation.

Stakeholders include everyone who will influence or be affected by a project. Every stakeholder looks to the project manager to lay out a proposed path of action, to guide resolution of conflicts among stakeholders, to set a consistent tempo of communication, and to establish a culture of competence so these stakeholders can trust the project manager and project team. Yet few of these stakeholders actually report to the project manager.

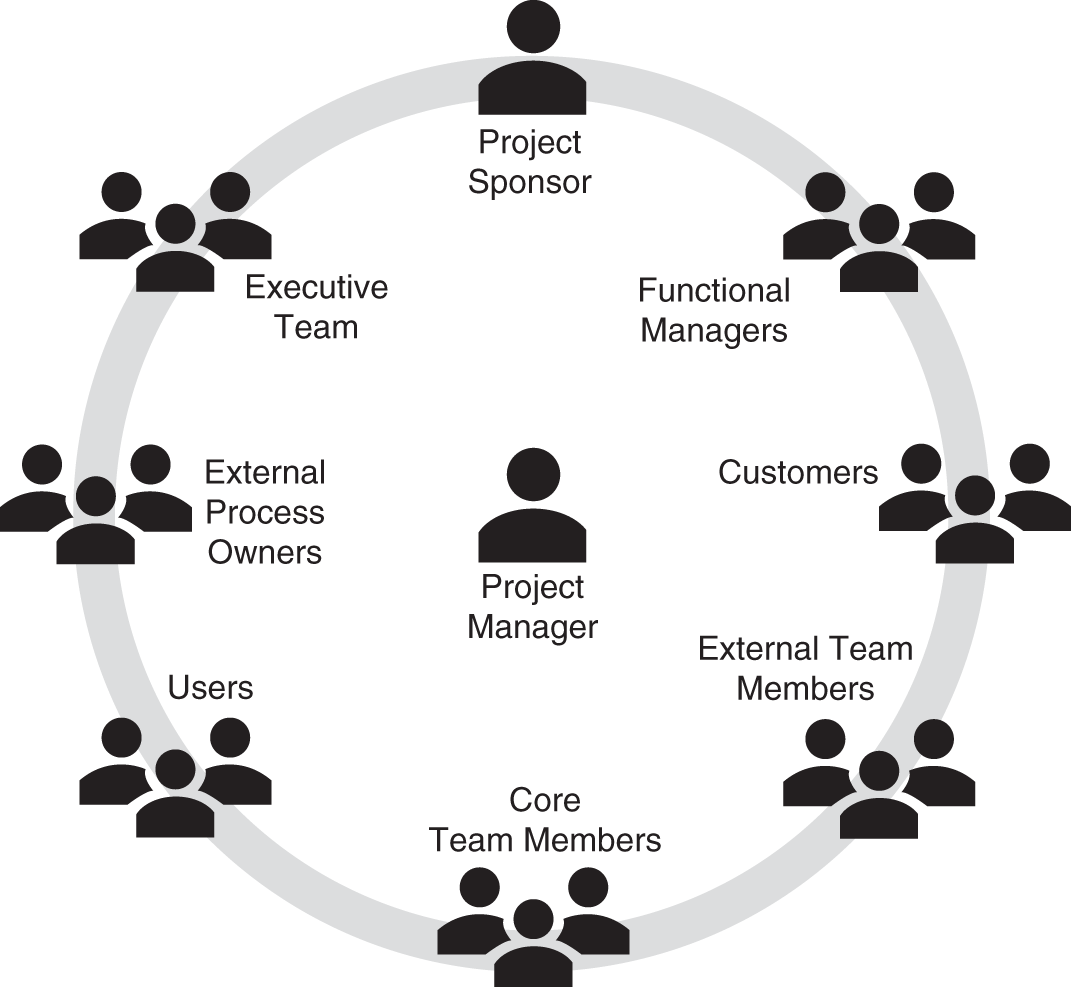

Typical organizational charts show a hierarchy of authority, illustrating who has authority over whom. Projects replace that hierarchical chart with one that looks more like a wagon wheel, with the project manager at the center (see Figure 2.1). It takes initiative and skill for the project leader to unify this diverse group, helping them cooperate in a common course of action. As we will see later in this chapter, project leaders must make up for their lack of formal authority with other strategies to build their influence.

FIGURE 2.1 Project managers lead a diverse group of stakeholders but have little direct authority.

BUILD A TEAM CULTURE SUITED TO A JOURNEY OF DISCOVERY

BUILD A TEAM CULTURE SUITED TO A JOURNEY OF DISCOVERY

Project teams make decisions day after day, often based on incomplete information. They do their best and when they are wrong, they regroup, look at what they've learned, and make new decisions. That takes a special kind of team culture, a culture that fosters collaboration, trust, and resilience. Project leaders set the tone and form the culture on their teams.

This description may conjure images of software developers, human resource policy makers, architects, and scientists, but does it apply to people wearing hard hats and safety glasses? Yes, because these intensely physical projects require constant decisions too. For example, Bill, who was leading a cabling project for a telecommunication company, got a call from the foreman of a field crew. Apparently, the specifications from the engineering department didn't match up with the reality the crew was facing. Bill drove to the site, climbed down into the utility vault, and listened to the foreman. “I explained what we wanted to accomplish and listened to the foreman's suggestion. I think that surprised him, but we came up with a solution together.”

A Culture That Fosters Collaboration, Trust, and Resilience

Picture a project team gathered to make a decision. They might disagree about what problem they're actually solving. They could disagree on the root cause, the options, who will have the authority to decide, and every other facet of the problem. But this is the team that needs to work through the problem. They must be able to listen to each other, actively disagree, learn from each other, develop a solution together, and maintain positive, respectful relationships.

When they make a mistake or assumptions fail, they don't turn negative. They bounce back and face reality with the same can‐do cooperation. That's resilience.

Not every team can do it. Collaboration and resilience require skills and attitudes that are intentionally fostered by the leader and the team. It is the team culture.

Team culture refers to the visible behaviors that demonstrate team values. If valuing divergent views is a team value, then active listening will be a team behavior. If optimum performance is a value, honestly giving and receiving feedback is a team behavior. Making the values visible and reinforcing the desired behaviors is a leadership activity that forms the culture.

Safety Precedes Trust

![]() In his book The Culture Code, Daniel Coyle identifies safety as a key foundational characteristic of what he calls high‐performing groups.1 In Coyle's research, his high‐performing groups were able to be vulnerable, which enabled them to improve. They could give and receive critical constructive feedback to improve themselves. That vulnerability requires a high degree of trust within the team. Before that trust could be established, individuals needed to feel safe. Bill, the telecom project manager mentioned above, had established that it was safe for the foreman to challenge the directions sent from headquarters. As a result, that foreman was willing to bring up other problems as they arose, knowing that Bill would listen and work with him on a solution.

In his book The Culture Code, Daniel Coyle identifies safety as a key foundational characteristic of what he calls high‐performing groups.1 In Coyle's research, his high‐performing groups were able to be vulnerable, which enabled them to improve. They could give and receive critical constructive feedback to improve themselves. That vulnerability requires a high degree of trust within the team. Before that trust could be established, individuals needed to feel safe. Bill, the telecom project manager mentioned above, had established that it was safe for the foreman to challenge the directions sent from headquarters. As a result, that foreman was willing to bring up other problems as they arose, knowing that Bill would listen and work with him on a solution.

Safety can't be taken for granted. Far too many important decisions are made while people silently watch and disagree. They choose not to participate rather than have their opinion dismissed or feel punished for voicing a contrary view.

Coyle quotes Dave Cooper, a retired SEAL Team Six Command Master Chief, on the difficulty and importance of achieving this level of trust. “When we talk about courage, we think it's going against an enemy with a machine gun. The real courage is seeing the truth and speaking the truth to each other.”

Why does it take courage to see the truth and speak the truth to each other? Because it isn't always safe. Yet what project manager does not want project team members who will see and speak the truth?

Building Project Team Culture Is Intentional

Among the many challenges facing a new project, establishing a culture of safety and trust that will support collaboration is clearly paramount. Team culture can't be left to chance. Chapter 15 contains a checklist of specific strengths that a project leader can foster to build the positive culture and collaborative capability of a team.

TEMPORARY TEAMS FORM BEFORE THEY PERFORM

TEMPORARY TEAMS FORM BEFORE THEY PERFORM

Each project team is formed specifically for their project. These people meet as strangers to the project. They do not begin as skillful collaborators nor with their hearts committed to the group. The evolution from cautious beginning to a cohesive, resilient, devoted team follows a predictable pattern that is well established. The model articulated in 1967 by Bruce Tuckman, which has been referenced and expanded upon ever since, identifies five stages of team development, stages that every team will experience from their initial meeting until the team disbands. These stages—Forming, Storming, Norming, Performing, and Adjourning—create a common vocabulary for discussing team building.

Evolve Your Leadership Style

![]() Project leaders benefit from understanding these stages for two key reasons: It provides guidance on how to take a team from one stage to the next as rapidly as possible, and the stages guide the leader's choice of style.

Project leaders benefit from understanding these stages for two key reasons: It provides guidance on how to take a team from one stage to the next as rapidly as possible, and the stages guide the leader's choice of style.

Do we really need to choose and change our leadership style throughout a project? Isn't our style a reflection of our own personality? According to Tuckman's model, our teams need different styles as they progress from one stage to the next. It makes sense that a team that is high performing allows a leader to be more hands‐off. It also makes sense that a team that is just beginning needs strong direction.

Read about the stages and how each informs our leadership style in the box on the subsequent pages. When we grasp the distinction between stages, we can flex our style to the needs of the team.

Self‐Managing Teams Are Developed

Self‐Managing Teams Are Developed

Teams that reach the Performing stage are largely capable of managing themselves. The maturity of these teams makes them resilient, productive, and desirable. Agile frameworks often call for self‐managing teams who exhibit these characteristics. These teams are assumed to have the skills that enable communication, planning, conflict resolution, and overcoming obstacles. The reality of Tuckman's stages challenges this assumption. Project leaders using Agile frameworks should see self‐managing teams as a desirable goal and be ready to invest in team development until the team demonstrates its maturity.

Attending to Team Health

![]() The project team is the engine of productivity. Like attention to your vehicle's health, proactive care and regular maintenance will extend the life of the team and reduce breakdowns.

The project team is the engine of productivity. Like attention to your vehicle's health, proactive care and regular maintenance will extend the life of the team and reduce breakdowns.

BUILD PERSONAL AUTHORITY AND INFLUENCE

BUILD PERSONAL AUTHORITY AND INFLUENCE

As described in Figure 2.1, project managers are expected to provide direction to many people and groups without direct authority over them. This direct authority, which is based on their position in the organization, is known as formal or legitimate authority. When project leaders lack positional authority they must supplement it with personal authority. The two most important sources of personal authority for a project manager are expert and referent authority.2

Expert authority is the respect afforded to a person due to their knowledge and ability. Project leaders can quickly develop expert authority through effective use of the project management techniques described in this book. Running meetings, clarifying scope, clear communication, and structuring a planning session are all examples of activities that, when performed well, will earn the respect of every stakeholder involved.

The Project Manager as Subject Matter Expert

The Project Manager as Subject Matter Expert

A subject matter expert, often called an SME, is a person with specific technical expertise. It might be a structural engineer specializing in freeway bridges, a biologist with deep knowledge of an endangered species, or a software architect who has previously used a unique technology. Their specific knowledge is called upon when solving a technical problem or planning work in their domain of expertise.

Project managers routinely develop specific technical knowledge over their careers prior to assuming a leadership role. This expertise, however, might undermine a leader's efforts to develop a cohesive group that is willing to give and take critical constructive feedback. The strongly stated views of an industry expert can easily discourage less experienced team members to voice contrary ideas.

Humility Builds Expert and Referent Authority

![]() Confident technical expertise tempered by humility is a very appealing combination. The sports star who credits their teammates rather than themself gains respect. The technical expert who listens to others, passes credit around, and models respectful disagreement builds another kind of authority, known as referent authority. This is the ideal style for the project leader with technical expertise.

Confident technical expertise tempered by humility is a very appealing combination. The sports star who credits their teammates rather than themself gains respect. The technical expert who listens to others, passes credit around, and models respectful disagreement builds another kind of authority, known as referent authority. This is the ideal style for the project leader with technical expertise.

Referent authority is the respect and admiration of others. Some people have the knack for gaining referent authority easily, through their natural friendliness and social ability. More enduring referent authority will be earned through integrity, transparent dealing, admitting mistakes, and being trustworthy.

Every stakeholder responds to expert and referent authority. Customers, suppliers, other departments, upper management, and certainly the team, all want a project leader who has earned their confidence and respect.

PROJECT LEADERS NEED POLITICAL SAVVY

Facing a breadth of stakeholders, project leaders must be able to influence people and decisions beyond their direct control. Building this influence includes skills known as political savvy.

The term office politics rarely has a positive connotation. It stirs emotions and memories of unfair influence and decisions that seem based on relationships rather than facts. But politics are real. To deny their existence is to disarm oneself. Particularly in a project environment, where cross‐functional stakeholders have competing visions and big decisions are being made, political savvy is a necessary skill. Let's listen to some experts who've authored books on political savvy as they describe the reality of politics within organizations:

- Joel DeLuca defines politics as “leadership behind the scenes.”3 Rick Brandon and Marty Seldman write,

- “Organizational politics are informal, unofficial, and sometimes behind‐the‐scenes efforts to sell ideas, influence an organization, increase power, or achieve other targeted objectives.”4

These authors make several points that apply to every project leader:

- There are times when politics are the only way that important work gets accomplished.

- Political action can have good or bad intent. It can serve the interests of the organization (good) or merely the interests of the individual (bad).

- Politics exist. We ignore them at our peril. It's better to build political skills and use them to advance our project and protect our team.

- Becoming politically savvy takes experience. It is far more of an art than a science.

Developing political savvy, like other important leadership skills, can be learned and practiced. Add this topic to your professional development list.

Build a Network of Authority

Build a Network of Authority

Building personal authority is the mark of a strong leader, but personal authority just isn't enough. The effective project leader will also build a network of formal authority, the authority represented by organizational structures and policies. Here are two guidelines for developing a network of formal authority:

- Make the project sponsor a partner with authority. A sponsor is a person with more formal authority than the project manager who is accountable for project success. Establish a pattern of regular communication and reinforce the alignment of project goals with the sponsor's goals. It would be great if the sponsor was proactive and fostered this relationship, because they need an effective project manager. When that doesn't happen, a project manager will have to take the initiative and engage the sponsor to build the partner relationship. Chapter 6 contains more details on the role of a project sponsor.

- Involve the decision makers early. Authority for project decisions comes from many places. Procurement policy is a good example. A project that uses outside materials and services will follow the organization's rules for establishing contracts and making purchases. These rules do not change just because a project manager has a charismatic personality. That project leader should work to understand the rules and then involve the right people in the project. Figure 2.1 shows the breadth of stakeholders influencing a project. Each group has authority for different decisions. Build a network of authority by knowing who to involve early and why. Chapter 6 contains more details on the interests and authority of these groups.

Developing a reputation for transparency and competence will go a long way toward building these networks of authority. Remember that effective use of the science of project management is the best way to win the confidence of these stakeholders.

YOUR DECISION TO LEAD

YOUR DECISION TO LEAD

What you are stands over you and thunders so, I cannot hear what you say to the contrary.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson

The breadth of project management techniques in this book can distract us from the primary responsibility of the project manager: to lead all the people engaged in the project. The science of project management—estimating, change control, status reports—can be learned and mastered through practice. Developing the art of leadership is a lifelong challenge. These final recommendations summarize project leadership in action.

Be Intentional

Leadership is not a by‐product of performing project management activities. Leadership begins with choosing to see oneself in the role of leader and influencer and embracing that role.

Be conscious that all eyes are on the leader and the leader sets the tone. Anyone who has had the experience of being promoted from within a team to leading the project has felt the eyes of the team as their former peers suddenly have new expectations of them.

Maintain the Strategic Vision

While team members focus on the near‐term problems and tasks, the project leader maintains a steady focus on the purpose and value of the project and the path toward the goal. This steady focus ensures that tasks are performed and problems solved in the context of the overall goals of the project.

Inspire the Team Through Example

Our actions demonstrate our attitudes and our values. The energy, attitude, and commitment of the team rarely rise above those of the leader. Choose to model the culture you want.

Steer Decisions to the Science of Project Management

Project management is a set of rational, analytical techniques that support decision‐making, even when it is necessary to make assumptions. Facts and objective evidence must be the foundation of realistic expectations and responsible assumptions. Wishful thinking and unfounded optimism have done great damage to many projects. Challenge every stakeholder, from team members to the highest‐level executives, to use reliable facts to drive decisions.

Show the Courage to Speak the Truth

On this journey of discovery, the news is not always good. An optimistic business case will unravel when assumptions don't come true. Mistakes happen. Reporting productivity problems to customers and management is nobody's favorite duty. But bad news cannot be ignored. Being in the spotlight takes courage. When faced with this situation, make the tools of project management work for you. Create a narrative based on facts and proven analytical methods. This will be difficult and worthwhile. You will earn the respect of your team and build credibility among all stakeholders. Courage makes you a stronger leader.

END POINT

END POINT

Projects are a journey of discovery. Every project breaks some new ground and every project requires the coordinated work of a diverse group of people. The project team, customers, suppliers, executives, and all the others involved in making decisions and performing the work cannot function without someone to create focus and facilitate their contributions. Fulfilling that leadership role is the primary job of the project manager.

Project managers benefit from the same leadership skills that help functional managers, but they also face unique challenges. Their team must Form before it can Perform, which means they must help a group of strangers develop into a cohesive, productive unit. The constant need for collaboration and problem‐solving requires a special team culture, one that allows for active disagreement while maintaining positive relationships. Finally, project leaders must lead and influence a breadth of stakeholders far beyond their formal authority.

In response, strong project managers choose to see themselves as leaders first. They build their own authority and credibility through the effective use of the science of project management. They use tools such as change control, risk identification, and writing a charter to manage expectations and create common understanding.

This book begins with an emphasis on leadership in order to establish a purpose and context for the subsequent chapters. For every concept in every chapter, ask yourself, “How would this help bring people together to make decisions and take actions in the best interest of the project?”