CHAPTER 5

Project Initiation: Turn a Problem or Opportunity into a Business Case

INTRODUCTION

Of all the decisions made in the life of a project, which one will have the greatest impact?

The answer is the first decision, the decision to pursue the project. That decision puts all the wheels of execution into motion and leads to a chain of events that could potentially go on for years, depending on the nature of the project.

With that in mind, it would make sense that any and every decision to launch a project is preceded by careful analysis of the potential benefits, costs, resource requirements, strategic alignment, and many other factors associated with the project. The key deliverable of project initiation is a project business case, which is variously referred to as a project justification, a proposal, or a similar term.

This chapter emphasizes the importance of the project initiation process: that launching a new project should rely on disciplined, thorough analysis, and that any project, no matter how valuable, must be considered in the context of the organization's other projects and strategies. We will place project initiation into the context of the entire project life cycle, examine the skills and techniques required during initiation, and recommend guidelines for turning a problem or an opportunity into a project business case. This chapter also introduces a powerful technique, the Logical Framework Approach, which has been proven on major projects around the world, yet has only recently found its way into corporate decision‐making processes.

PROJECT INITIATION'S PLACE IN THE PROJECT LIFE CYCLE

PROJECT INITIATION'S PLACE IN THE PROJECT LIFE CYCLE

Even though the decision to pursue a project is enormously important, the steps and processes leading up to that decision are outside the traditional scope of project management.

The reason for this is apparent when we consider who really conducts the initiation work. Throughout this chapter we view project initiation from the perspective of the owner, or sponsoring organization, the entity that will fund the project and enjoy the benefits. The project owner may not be responsible for project execution, which is another reason that initiation is separated from project management. Two classic examples include a real estate development company that hires a general contractor to build an apartment building or a marketing department that relies on its information technology department to implement a customer relationship management (CRM) solution. Both the real estate development company and the marketing department are responsible for the feasibility study that precedes project authorization and execution. How will the project deliver value? The answer is found during the project initiation activities.

A MINI‐ANALYSIS PHASE OR A COMPLETE PROJECT

Project initiation consists of the work required to study a problem or opportunity. The result can be a recommendation to launch a project. It can also be a decision that the problem or opportunity being studied just doesn't merit further action.

This analysis work often begins informally. It could be a recurring problem that sparks a manager to assign someone to “see what we can do about that.” Or it could be an idea for a new product that will create or expand a market or reduce operational costs. These new ideas can come from anywhere, including attending trade shows, reading articles, suggestions from employees, and listening to customers. Once we see that initiation starts informally, it is easy to see why the rigor that should be applied is sometimes missed. That's why it is important to have clear criteria for approving a project. No matter how misty or ambiguous the project's beginning, it will eventually undergo a formal analysis.

FIGURE 5.1 Problems and ideas start out as being vaguely defined. The initiation activities generate specific facts and assumptions that feed a project approval decision.

Figure 5.1 shows where project initiation connects to the product development life cycle discussed in Chapter 4. (To see project initiation through the lens of requirements evolution, see Figure 5.2, later in this chapter.) The work to develop a project business case could be thought of as a mini‐analysis phase. It is sometimes called a feasibility study. If the effort is significant enough, it becomes a project in its own right.

THE ROLE OF A PROJECT MANAGER IN PROJECT INITIATION

If initiation activities happen before a project is formally authorized, what is the role of a project manager during initiation? There are three possibilities: manage the initiation phase, perform the analysis work, or merely review the resulting business case after the project is approved.

The effort to accomplish the analysis could be large and complex, and therefore require the skills of a project manager to coordinate the people and work as in any project.

People who have project management skills may also have the ability to perform the work of initiation. As we'll see in this chapter, that work consists of stakeholder analysis, problem solving, root cause analysis, creative design of potential solutions, and cost‐benefit analysis. The skills and techniques required for this work fall outside the normal boundaries of project management. However, these capabilities are extremely complementary to project management, so it is realistic for one person to have the ability to both manage the initiation work and also to perform that work.

It is also possible that the project manager who is ultimately responsible for managing an approved project has no involvement at all in project initiation. In fact, this tends to be the norm. Whoever will pay for the project may assign a person or team to generate requirements and produce a business case. For example, within an information technology organization, the work is usually done by business analysts. This handoff, however, has a potential risk. Will the project manager really understand the business value that the project is intended to deliver?

In any of the scenarios described above, the more a project manager can at least understand all of the results of the analysis that is performed during initiation, the better he or she will be at managing the project to deliver on the business case. The topics in this chapter may be outside of your direct responsibility as a project manager, but they will increase your overall contribution to your projects and your organization.

Initiation Is Linked to Project Portfolio Management

Project initiation produces a business case that is the basis for evaluating the project. If an organization has a portfolio management process in place, each business case provides consistent information and all potential projects are ranked against each other. Project portfolio management, described in Chapter 21, ensures that the limited resources of an organization are assigned to the projects that provide the best results, whether those results are measured in purely financial terms or in other, more intangible ways. As we examine the standard content of a project business case later in this chapter, we'll see how business case content reflects portfolio selection criteria.

A BUSINESS CASE DEFINES THE FUTURE BUSINESS VALUE

A BUSINESS CASE DEFINES THE FUTURE BUSINESS VALUE

Projects are approved in order to achieve benefits. The business case articulates these benefits in contrast to the expenses that will be incurred. A useful business case, therefore, explains the core reason for the potential project, the balance of expected costs and expenses, and begins to articulate the future state that will be achieved if the project is performed.

To consider whether a project is worthwhile, it is useful to reflect on the three dimensions that the design firm IDEO promotes and that were introduced in Chapter 4: desirability, viability, and feasibility. These are directly relevant for evaluating a commercial product, but in general they form the lens through which any future project can be judged.

- Desirability. Will the functionality that we intend to deliver be compelling to potential users? If we expect to generate revenue from these users, how much can we realistically expect they'll pay? Public agencies must consider this factor if they are contemplating projects from bike lanes to tolled highways.

- Viability. What is the needed return on investment? Viability looks beyond the implementation cost; it balances the lifetime cost against the lifetime benefit. Lifetime costs and benefits span development on the front end, operating costs and revenues, and the costs of decommissioning when it reaches the end of its life.

- Feasibility. Is this technically possible? What technical risks will exist over a solution's lifetime?

The process of initiation explores these questions, and the business case found at the end of this chapter summarizes these answers.

BUSINESS RISK AND PROJECT RISK

Building a business case demands that we make assumptions and forecasts—all of which could be wrong. A real estate developer invests in a new apartment complex, breaking ground 12 months before the first tenant will move in. And it will take years of rental income before the project breaks even. Will the demand for these apartments be sufficient over the years to maintain high occupancy? Will the overall rental market produce the anticipated rental rates? These questions address business risk, the risk an owner bears when investing in a business venture.

Business risk is separate from project risk. Project risk is primarily concerned with delivering the promised deliverables for expected cost and schedule. If the apartment complex is built correctly, delivered on time and budget due to effective project management, then the project risk was successfully managed. The business risk remains, throughout the life of the apartment complex. Business risk is outside of the project manager's responsibility.

MANAGING REQUIREMENTS IS TIGHTLY LINKED TO PROJECT INITIATION

MANAGING REQUIREMENTS IS TIGHTLY LINKED TO PROJECT INITIATION

Judging the success of a project at completion is tied to setting the purpose and goals as the project is initially conceived. Setting this target relies on eliciting and managing requirements, which falls within the domain of Requirements, a topic that is explained in greater detail in Chapter 22.

For the purposes of creating a project business case, the most important requirements concept is that there are different types of requirements, as shown in Figure 5.2. The earliest requirements are called enterprise requirements, because they describe the needs of the enterprise that is contemplating the project. Another term for these initial, high‐level requirements is business requirements. Enterprise requirements describe what various stakeholders will be able to do in the future as they use the project's deliverables.

FIGURE 5.2 Requirement types evolve throughout the development life cycle. Establish enterprise requirements during project initiation.

Business requirements are tightly linked to the benefits the project will deliver, because if we can deliver the capability described in the requirement, the stakeholder will enjoy a benefit.

The business case template described in this chapter includes a section for business requirements.

Monitoring Benefits Realization Begins with the Business Case

For most projects, the benefits they produce won't be experienced until the project is completed and the change has become operationalized. The project may be closed down and the project team dispersed long before the value of the project investment is realized. That causes a common problem, which is that no matter how thoroughly we study a project before it is launched, the result is not measured. When that happens, we don't really know whether the desired cost savings materialize or the market share increases, which reduces the validity of the project approval process.

One source of failure for benefits monitoring was expressed by a project management office (PMO) leader at a hospital: “We have a hard time seeing the impact of an individual project. There are so many variables that affect our environment that we can't always draw a line to the project.” She said that the hospital tracked many important metrics and that projects were initiated and aligned to these governing metrics. But strategic metrics are often lagging indicators, meaning they are the result of many factors.

The initiation stage is the time to drill down to the root cause to see the driving metrics. The goal of the project will be to address the root cause. That means monitoring benefits realization should be focused on watching the change that occurs to the root cause. A metric related to a root cause is sometimes referred to as a leading metric, because changes here lead to changes in the strategic metric.

Companies are placing an increasing importance on monitoring the actual benefits of their projects. The content of a business case should clearly identify what will be measured, when, and how. The project team may disperse before the results materialize, so include a recommendation for the organization that should be responsible for monitoring the benefits.

The ability to drill down on a process to create measurable benefit metrics also falls into the domain of requirements engineering.

It is worth noting that it takes skill to articulate enterprise requirements. The stakeholders who want to see a change often have a vision of what they want, but they can't describe it in a way that fosters the best problem‐solving approach. Business analysts contribute this skill on information technology projects. Through their facilitation skills, they help stakeholders identify what they really want to accomplish, which expands the realm of possible solutions. This skill is directly related to a recommended practice described later in this chapter: Clarify the problem before proposing a solution.

The Logical Framework Approach Connects Requirements with Metrics

It should be clear that connecting the strategic goals of a project with a specific measurable outcome increases the rigor of the business case. A method for doing this is called the Logical Framework Approach. At the end of this chapter you'll find an introduction to this technique, written by Terry Schmidt, who was part of the team that pioneered it more than 30 years ago. Make a Logical Framework a part of any business case.

COMMON PRINCIPLES FOR PROJECT INITIATION

COMMON PRINCIPLES FOR PROJECT INITIATION

Will an automaker consider introducing an electric sports car using the same process that a marketing department uses to analyze the addition of a CRM system? Does a real estate developer research the feasibility of a new shopping mall the same way a university evaluates the addition of a purely online degree program? Clearly, these are all quite different types of potential projects, and the proper analysis for each one varies. The most complex products require the most sophisticated and time‐consuming evaluation. The automaker and major real estate developers have sophisticated procedures and legions of professionals trained to perform rigorous analysis. That just isn't possible or appropriate in many organizations. But that doesn't mean every project can't apply some commonly accepted best practices before plunging into a project.

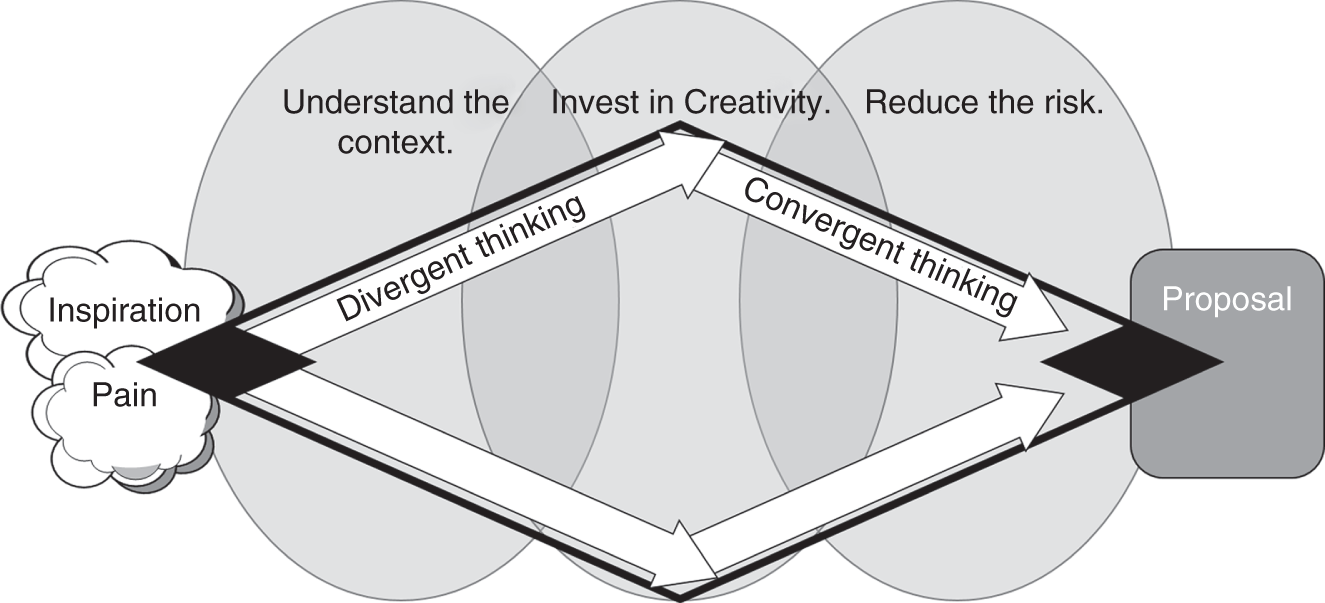

FIGURE 5.3 Project initiation begins with divergent thinking to expand our understanding of the project before attempting to choose a solution.

Figure 5.3 illustrates the principles that transcend industries during project initiation:

- Understand the context of the issue through the eyes of all stakeholders.

- Invest in creativity. Initiation presents the greatest opportunity to approach the issue with fresh, original ideas.

- Be methodical in evaluating the options and testing assumptions. Risk identification in this phase pays huge dividends.

The wise organization is able to extrapolate from the guidelines that follow and match them to their projects.

Involve a Wide Variety of Stakeholders

Stakeholders are all of the people who will engage in the project or be affected by it. As we'll see in Chapter 6, good project managers invest in early identification of stakeholders as the first step in understanding a new project.

Stakeholder involvement is even more important and more difficult during project initiation—more important because this is the time we set the goals and direction of the project, and more difficult because there will be a much broader group of potential stakeholders during this early analysis. Use the following perspectives as a guide for your own efforts to include and engage the right stakeholders:

- Understand the problem or opportunity from the perspective of everyone it will affect. An airplane manufacturer must consider the maintenance crews, pilots, and passengers when designing a new aircraft. Imagine all the people who will touch the product during the full product life cycle. What are their concerns or desires related to the problem or opportunity?

- There may be advocates for change and advocates for maintaining the current state. Why? What stake does each have in making (or not making) a change?

- Federal, state, and local government agencies are full of stakeholders. Laws and regulations form constraints to the situation. Zoning laws, for example, restrict the use of real estate, governing what types of buildings and activities are allowed.

- Integration with existing systems is an issue on all kinds of projects. An e‐commerce website will integrate with a secured payment processor. A military fighter jet that needs to refuel in flight must consider the tanker aircraft that provides the fuel. A new mobile phone app must work with the phone's operating system.

Viewed from this perspective, it might seem that there is a never‐ending list of stakeholders and that seeking them all out will take an eternity. That is not the intention. However, it reinforces that the analysis performed to build a project business case is not trivial and often requires specialized skills and knowledge. The bottom line is that listening to stakeholders will expose requirements and constraints. The earlier these are exposed, the cheaper they are to manage.

Chapter 6 is devoted to stakeholder identification. We'll see that casting a wide net for stakeholders during initiation is just the beginning of delivering value to stakeholders.

Clarify the Problem Before Proposing a Solution

It seems pretty obvious that we should agree on what problem is being solved before coming up with great ideas to solve it, but not doing this is a classic mistake. Failure to clarify the problem is a common source of disappointment, particularly because it is routinely discovered after the project is complete. Call it human nature. Reinforce it by applauding it as being decisive and action‐oriented. Do it because “that's what the customer asked for.” But taking action without clarifying the problem will always be a mistake.

Every sound product‐development or problem‐solving approach shares this principle. Define the problem as the gap between the current state and the ideal state, often literally referred to as gap analysis. The ideal state should not include a specific solution, but rather the capability we want but don't have. This is the tie to enterprise requirements, as described earlier in this chapter. The enterprise requirements are the ideal future state. The downloadable Project Business Case template specifically calls for this in the requirements section.

Describe the primary success criteria in terms of what the organization or customer will be able to do as a result of the project's successful completion. Many completed projects are a disappointment to the customer because they don't really address the core business or functional need that the customer had. It takes skill to uncover and document enterprise requirements, because they usually lurk beneath the surface—below the symptoms of the problem or the customer's perception of what solution should be implemented. Remember that these requirements will be elaborated on during subsequent phases of the project.

Wherever the need for innovation is high, this factor becomes even more important. By disciplining ourselves to focus on defining the problem, we expand the range of possible solutions. We are able to go beyond the initial solution that seems so obvious and explore all the possible ways to achieve our goal. Further, the “ideal state” requirements provide the framework for evaluating the possible alternatives.

Invest in Creativity

Maybe it goes without saying that when we analyze a problem or opportunity we need to generate several options, rather than just pursue the first one that bubbles up. That is certainly the only way that truly new ideas are created.

The initiation stage is perhaps the greatest opportunity for adding value through creativity in the life of the project. It is the stage where the least amount of money has been spent, and the greatest number of options exist. The cost of exploring a new idea can be small, perhaps a few days or weeks. Learning and insights at this early stage create other possibilities. Conversely, once the project is approved with a solution, budget, and deadline, the appetite for innovation and original approaches is lost in the focus on efficiency.

According to Peter Drucker, the famed management consultant and writer, “Efficiency is doing things right; effectiveness is doing the right things.” Here, before we put the project team in motion, is the time to ensure we are doing the right thing.

Investing in creativity takes courage. Everyone wants the fresh, insightful solution, but nobody wants to pay for the twenty ideas that came before it that just wouldn't work. Testing assumptions, experimenting with new approaches, and a general willingness to “get outside the box” do take time and effort, yet that is the only way to break away from the usual solutions.

Of all the guidelines for investing in creativity, here is the most relevant for project initiation:

Creativity in the workplace is anchored by our understanding of the problem or opportunity. Creativity for innovation finds its inspiration in understanding the stakeholders and their needs.

Creativity is no accident. It requires time and intention. Building creative activity into your project initiation activities will require its own act of creativity. Yet, now more than ever, creativity pays enormous dividends.

Quantify the Benefits and Costs of the Alternatives

Quantify the Benefits and Costs of the Alternatives

For each of the many possible approaches that have been proposed, rank them against the enterprise requirements and quantify their benefits and costs as much as possible. Quantifying the benefits will demonstrate how the alternatives vary in their results. Quantifying the costs will provide a foundation for a financial analysis, such as return on investment (ROI). Since most alternatives analysis requires us to compare apples and oranges (options that have different advantages and disadvantages), finding ways to quantify the costs and benefits will allow us to see why we might want to pursue a lower‐cost option that produces a lesser result. Or it could justify making the big investment with the big payoff.

As this analysis is performed, keep in mind that a similar comparison will be made for the proposed project and other potential or active projects during final project selection. This project must not only produce benefits that outweigh its costs, but the project must be a better use of the firm's limited resources than other projects.

Use Risk Management to Improve the Solution

It takes a lot of courage to develop an innovative idea. It takes even more courage to expose the idea and invite criticism. But doing that will make your best solution even better.

The risk management process described in Chapter 8 can be used to uncover weaknesses to examine both the solution itself and the planned implementation.

Invite others to play the role of “devil's advocate,” to critically challenge every assumption about your best idea. Ask questions about the three IDEO variables: viability, desirability, and feasibility.

Go beyond documenting assumptions: actually test them as much as possible. The expense of testing assumptions in this phase will be far smaller than the cost of finding out your assumption isn't true during implementation or after the project is over. (Recall the introduction to Lean Startup in Chapter 4, which emphasized constant experimentation.)

Risk management is an excellent counterpoint to creativity. It subjects all of our crazy, out‐of‐the‐box ideas to rigorous evaluation. When we do find problems or weaknesses, that doesn't mean our fresh idea isn't any good, it just means it can be made better.

PROJECT SELECTION AND PRIORITIZATION

PROJECT SELECTION AND PRIORITIZATION

It has been said that you can't compare apples and oranges. It is a saying that characterizes a choice between two options with different benefits and disadvantages. Choosing between potential projects frequently presents that same dilemma.

A seasoned executive can justifiably rely on her or his intuition and judgment to choose between two projects, even if they are an apple and an orange. That won't work for project portfolios. The range of projects that confront a portfolio steering committee can turn the “apples versus oranges” dilemma into a fruit salad. Use a consistent business case format and selection criteria to put a decision‐making framework in place.

Use Standard Financial Models to Compare Projects

Should you choose the 4‐month project that will bump revenue up 1 percent for 12 months or the project that will take 18 months to complete that could open up a new market? That's an apples and oranges comparison.

Financial models exist to compare these types of projects. These models allow you to compare the costs and forecast monetary benefits of very different kinds of projects in an attempt to create side‐by‐side comparisons.

Examples include benefit‐cost ratio, payback period, and net present value. Any company with a standard business case format will tell you which of these methods is required.

![]() Several financial models are demonstrated in the PMP® Exam Prep video Project Selection, which is found at www.VersatileCompany.com/FastForwardPM.

Several financial models are demonstrated in the PMP® Exam Prep video Project Selection, which is found at www.VersatileCompany.com/FastForwardPM.

BASIC BUSINESS CASE CONTENT

BASIC BUSINESS CASE CONTENT

The outcome of project initiation should be a business case that is suitable for a selection process. Selection may be a part of a total project portfolio management process, or it could be reviewed by a single manager or executive who has the authority to commit the resources.

The basic content of the business case overlaps the content found in the project charter described in Chapter 7. That makes sense because both are used to move a project from an inspiration to a tangible, achievable goal. Since the business case is written first, any overlap with the charter represents an opportunity either to verify an earlier assumption or to develop that topic in greater detail. The business case that follows will become much more powerful when accompanied by the Logical Framework Approach described at the end of this chapter.

As previously emphasized, the information and analysis required to select a project will vary dramatically depending on your industry and the size of your projects. The content described here addresses the minimum topics most project selection boards require. You may find it useful to reference the online Project Business Case form as we explore each section of the business case.

1. Project Goal

State the specific desired results from the project over a specified time period. Remember, this is the business value that we begin to experience after the project completes. For example, the goal of a training project could be: “This project will improve our ability to plan projects with accuracy and manage them to meet cost, schedule, and scope goals.”

2. Problem/Opportunity Definition

Describe the problem/opportunity without suggesting a solution. The people approving the project must understand the fundamental reason the project is being undertaken. This problem/opportunity statement should address these elements:

- Describe the problem/opportunity. If possible, supply factual evidence of the problem, taking care to avoid assumptions.

- Describe the problem/opportunity in the context of where it appears in the organization and what operations or functions it affects.

- List one or more ways to measure the size of the problem. Qualitative as well as quantitative measures can be applied.

3. Proposed Solution

Describe what the project will do to address the problem/opportunity. Be as specific as possible about the boundaries of the solution, such as what organizations, business processes, information systems, and so on will be affected. If necessary, also describe the boundaries in terms of related problems, systems, or operations that are beyond the scope of this initiative.

4. Project Selection and Ranking Criteria

Ideally, your firm has specific selection or ranking criteria that are addressed here. If a formal project portfolio management process exists, this section will match the categories that assist a selection board in ranking one project against another.

- Project benefit category. Projects typically fall into one of the following categories:

- Compliance/regulatory. Laws or regulations dictate the requirements for the project.

- Efficiency/cost reduction. The result of the project will be lower operating costs.

- Increased revenue. For example, increased market share, increased customer loyalty, or a new product could all produce increased revenue.

- Portfolio fit and interdependencies. How does this project align with other projects the organization is pursuing and with the overall organization strategy?

- Project urgency. How quickly must the organization attempt this project? Why?

5. Cost‐Benefit Analysis

This section summarizes the financial reasons for taking on the project. It consists of an analysis of the expected benefits in comparison to the costs and attempts to quantify the return on investment.

- Tangible benefits. Tangible benefits are measurable and will correspond to the problem/opportunity described. For each benefit, describe it and quantify it, including a translation of the benefit into financial terms such as dollars saved or gained. Include any assumptions you used in calculating this benefit. Forecast benefits are usually not certain, so describe the probability of achieving the result. This is the place to establish the benefit‐realization metrics that will be monitored after implementation.

- Intangible benefits. Intangible benefits are difficult to measure, but are still important. For example, reducing complexity in a task may increase employee job satisfaction, a worthwhile benefit but a difficult one to measure. Again, describe the benefit, the assumptions used to predict the magnitude of this benefit, and the probability the benefit will be realized.

- Required resources (cost). What labor and other resources will be required? Include a comment about the accuracy of these figures. Typical cost categories include internal (employee) labor hours, external labor, and capital investment. New ongoing costs to support the result of the project should be recognized but separated from the project costs.

- Financial return. There are many financial methods that compare the tangible up‐front cost of the project with the expected tangible benefits achieved over time. Learn about some of these models using the PMP® Exam Prep video Project Selection, referenced earlier in this chapter.

6. Business Requirements

These are the enterprise requirements we've emphasized earlier in this chapter. Describe the requirements from the owner/customer perspective. If you describe a requirement using one of the following phrases, you are more likely to be accurately describing the true end state desired by the customer.

The project will be judged successful when …

We know ___________________________________________.

We have ____________________________________________.

We can _____________________________________________.

We are _____________________________________________.

You can substitute the names of specific users or customers in these statements, such as “Project sponsors know the cost and schedule status of all projects for which they have responsibility.”

7. Scope

List and describe the major accomplishments required to meet the project goal. These may include process or policy changes, training, information system upgrades, facility changes, and so forth. Clearly an overlap to the project charter, the scope description in the business case is likely to be less detailed than the one developed for that document.

8. Obstacles and Risks

Describe the primary obstacles to success and the known risks (threats) that could cause disruption or failure. The difference between obstacles and risks is that risks might occur, but obstacles are certain to occur. Chapter 8 describes how the risk management process works continuously throughout the project to help identify potential threats and either avoid them or reduce their negative impact.

9. Schedule Overview

At a high level, describe the expected duration of the project (planned start and finish), significant milestones, and the major phases. This is an initial schedule estimate that will be refined during project definition and planning, but it is always useful to manage expectations by commenting on the accuracy of this schedule prediction.

DESIGNING A REALISTIC INITIATION PROCESS

DESIGNING A REALISTIC INITIATION PROCESS

Initiation can be a project. The research and analysis just described demand skill and effort. For some projects, initiation could take months or years. For smaller projects it will take hours. Clearly, a balance must be found between irresponsibly plunging into new projects and being stuck with “analysis paralysis.”

There are two key factors to consider when designing the initiation process: risk and estimating; and both are related to the inherent unknowns that exist at the time a project is approved.

- Risk. Risk management, as described in Chapter 8, is our process of identifying threats and opportunities and actively working to reduce the threats and optimize the opportunities. No matter how thorough the work during project initiation, our business case still contains many assumptions. Any forecasted costs or benefits are subject to change. So the question for our initiation process is: Have we studied the problem enough that we can accept the amount of uncertainty that remains in the business case? Or do we commit more resources and time to study it further?

- Estimating. We know that estimates are a reflection of the known and unknown remaining in the life of the project. The earlier the estimate, the less accurate it is. The only completely accurate estimate is for a project that is complete, because it has no surprises left. What amount of accuracy do we require to approve a project, and how will we update that estimate as the project is being executed?

A realistic project initiation process accepts that projects are approved based on many assumptions that won't be proved true or false until the project is under way or even completed. The phased estimating technique described in Chapter 12 is the best approach to striking the balance. The phase gate reviews described in Chapter 4 are designed to force the oversight committee to reevaluate the business case in light of what has been accomplished and learned in the previous phase.

PROJECT LEADERSHIP: FOCUS ON VALUE

PROJECT LEADERSHIP: FOCUS ON VALUE

Projects must deliver value, and that value must be clearly described in a business case. Project managers must use a critical eye when they read a business case. Is there really a clear connection between the requested deliverables and the hoped‐for results? Are cost and schedules rooted in reality? Can you prove the assumptions soon enough?

The fuzzy front end of any project requires strong critical thinking and abstract problem‐solving skills. Project managers who ask intelligent questions and challenge faulty logic provide enormous value.

It may not be easy to challenge the legitimacy of an assigned project, but the courage and skill to create or analyze a business case serves the organization and builds your influence and reputation.

END POINT

END POINT

The project management discipline has long focused on excellent delivery of projects. However, that ignores the most important question we can ask about the project: Why do it?

Project initiation starts with an idea or problem and performs just enough study and analysis to produce a project business case. It is a difficult task because it is a combination of discovery, stakeholder negotiation, problem solving, and financial analysis, and it may require considerable technical expertise. Because of the specialized skills and knowledge that are necessary, this work is often not performed by project managers.

The final pages of this chapter contain a description of the Logical Framework Approach, which produces a LogFrame. Together, the LogFrame and business case form a sound basis for evaluating a potential project and setting the target that will be monitored after the project is completed.

FAST FOUNDATION IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT

FAST FOUNDATION IN PROJECT MANAGEMENT

The biggest decision of a project may be whether to pursue the project at all.

The downloadable Project Business Case template covers the topics that executives will care about as they choose between competing ideas. Comparing projects can be like comparing apples and oranges. A consistent method for describing a candidate project will make the comparisons less emotional and more rational.

Download the form at www.VersatileCompany.com/FastForwardPM.

FIGURE 5.6 Logical Framework project plan to improve the purchasing/receiving/payment cycle.

PMP Exam Prep Questions

PMP Exam Prep Questions

- Which of the following statements is the most accurate distinction between projects and portfolios?

- There is no difference between portfolio and project management.

- Project management focuses on doing the right work; portfolio management focuses on doing the work right.

- Portfolio management focuses on doing the right work; project management focuses on doing the work right.

- Multiple portfolios make a project.

- Given the complex nature of projects, which area of change generally has the greatest impact?

- A change in the company that is creating the product

- A change in the market for which the work of the project is intended

- A change in the team on the project

- A change in the project

- Project A has an NPV of $150K over three years. Project B has an NPV of $330K over six years. Project C has an NPV of $170K over six years. Which of the following do you select?

- Project A

- Project B

- Project C

- Projects A and C

Answers to these questions can be found at www.VersatileCompany.com/FastForwardPM.