7

Achieve Alignment

WHEN THE AGENCY director returned from the first meeting he and his peers had with the department’s new secretary and immediately called the senior staff together, Elaine Trevino, the assistant director for management, knew they were in for some big news. Secretary Reese Fuller, coming into government after a fast-rising career in the financial-services industry, made it clear during the run-up to his nomination that he did not intend to lead the department in a business-as-usual style, and during his confirmation hearings, his intention received strong support from the legislators on the agency’s oversight committee. So, naturally, there was palpable tension in the room as the senior agency executives gathered to hear the director’s report.

To everyone’s surprise there was only one word on the director’s agenda placed before each chair around the table: “Change.” Somewhat puzzled, the executives leaned forward around the conference table and waited to hear what it meant. “Ladies and gentlemen,” the director began, “after almost fifty years of carrying out its mission in essentially the same way, this agency is about to undergo a fundamental restructuring. Secretary Fuller calls it ‘customerbased government,’ and it is his stated goal to implement this new approach to providing better public services within a year. The good news is that it does not rely on outsourcing and that a pledge has been made to employee unions that there will be no layoffs because of this effort. The challenge, however, is that we, along with every other agency under Secretary Fuller’s leadership, will now compete with businesses in the private sector for a large chunk of services we have been providing. It should be clear to everyone in this room that in order to come out on top in this competition we must shift our thinking and our ways of operating to become more entrepreneurial and more customer focused.”

The director then turned and looked directly at Elaine. “As assistant director for management,” he started, “I want you to do a fast but thorough analysis of what changes are needed in the way we are structured and the ways in which we now carry out our mission in order to position us for this new competition—competition with people who may be experienced in the methods and strategies of success in the marketplace, but who do not, as we do, have the depth of knowledge about the work we carry out. I look at this as an even playing field, and I believe that Secretary Fuller means it when he says he is not biased either way; his goal is better delivery of government services, regardless of who provides them. So, ladies and gentlemen, I believe that we have all the talent and other resources we need to succeed, and you may be certain that I have no intention of losing out in this competition. Each of you—as well as every employee—will have an important role to play in planning for and ultimately achieving our success. I am passing out the secretary’s memo that details the strategy for customer-based government. Please note that he is willing to suspend some of the regulations that could interfere with our restructuring for competition so long as our implementation plan makes sense. Elaine, I’d like your report in a month.”

As the senior staff huddled in the corridor outside the director’s conference room and leafed through the secretary’s memo, Elaine picked up on the usual mixture of reactions—cynicism, anxiety, and excitement. She had worked at the agency for almost ten years and was well familiar with its culture, its work systems, and the professional dedication of most of its employees. While she was confident in the agency’s basic capability to take on this new challenge, she was not naive about the kinds of changes that would have to be made to convert this large, rule-based monopoly into a quickfooted, flexible organization able to compete with the best that the business world had to offer. She was excited by the prospect, and her mind was filled with ideas before she even reached her office.

The first thing she did was enumerate the major goals for the agency’s implementation of the customer-based government (CBG) initiative: improve customer service; lower operating costs; increase flexibility in the use of resources to promote the pooling of skills, tools, and information; and streamline the entire organization to eliminate duplication and other structural drags on productivity. She then turned her attention to the problems.

As a typically organized government bureaucracy, the agency operated strictly by its organization chart and its carefully delegated authorities, all of which were designed to provide a stable, auditable mechanism for it to deliver services to its client agencies and justify its resource requirements to the executive and legislative bodies that controlled its budget. What such a structure could never do, however, was readily accommodate the kind of flexibility that was needed to succeed in an environment where the agency’s clients had the option to procure their services from another source.

Elaine spent the next two weeks reaching out to her peers, employee groups, and constituents, discussing the goals of the CBG strategy and soliciting ideas for its implementation. She also met with several academics whose research on organizational change provided her with insights into the dynamics of the transformation process. Then she began to prepare the report the director was expecting. When she finished, she knew that her findings and recommendations would, if implemented, create a period of turmoil within the agency. But she was convinced that the problems she identified and the strategic changes she proposed would position the organization not only to survive but to prosper in the new competitive environment of customer-based government.

Her proposed strategy had four elements:

• Introduce risk into agency operations by allocating portions of the agency budget to its clients to use in procuring the services the agency, as well as its potential competitors, provided. (This, Elaine believed, would stimulate creativity in reengineering work processes, reducing costs, and improving overall productivity.)

• Merge several of the agency’s existing support organizations into a single entity responsible for the new functions of bid preparation, performance measurements, and customer relations.

• Revise the existing compensation and incentive plan so it was more closely linked to performance.

• Convert the agency’s funding method from an appropriation system to a self-sustaining working capital fund that would support cost accounting, facilitate billing, value productivity improvement measures, and provide a financial P&L-type reporting system that measured revenues as well as expenditures.

In her report to the director, Elaine acknowledged the myriad technical difficulties in quickly implementing the strategy she recommended for redesigning and reorienting the agency so that it was better aligned to meet its new challenges. She insisted, however, that the main obstacle was not technical but cultural. The agency’s success in transforming itself would ultimately depend on behavioral changes at every level; implementing those changes, Elaine emphasized, was the principal challenge the agency faced. One week later the director gave Elaine the green light, and the real work began.

The Leader as Architect

The role of architect is unlikely to be a familiar one to most new leaders. Few managers get training in systematic approaches to organizational design because they typically have limited control over it in the beginning of their careers. It is commonplace for less senior people to complain about poor organizational design and to wonder why higher-ups let obviously dysfunctional arrangements continue. By the time you reach the middle-management levels of most organizations, however, you are well on your way to being complicit in the same tolerance of poor organizational structures that you earlier criticized. You are, therefore, well advised to begin learning something about how to assess and design efficient and effective organizations as soon in your career as possible.

Why? Because even the most perceptive, motivated, and charismatic of leaders cannot hope to accomplish much if the strategy is the wrong one; if the structure of the organization misdirects employees’ attention or, worse, contributes to conflict; if key processes and systems are inefficient or unreliable; if the organization’s skills are inadequate for the mandate at hand; or if the culture somehow inhibits the leader’s ability to institute change. Your overarching design goal, therefore, is to align the architecture with your objectives and the demands of the external environment as defined in the organization’s mission and objectives.

What is organizational architecture? It is the sum of these five critical elements, each of which represents an essential building block of any organization:1

• Strategy. The core approach that your organization will use to accomplish its goals.

• Structure. How people are situated in units and how their work is coordinated, monitored, and rewarded.

• Systems. The work processes used to carry out the organization’s assigned responsibilities.

• Skills. The capabilities of the various groups of people in the organization.

• Culture. The values, norms, and assumptions that surround the other four design elements and shape behavior.

Misalignments among any of these five elements can render even the best strategy useless. Though strategy drives the other four, it also is heavily influenced by them. For example, if you need to realign a previously successful organization, as Elaine Trevino did, you likely will have to alter strategy and bring structure, systems, skills, and culture into alignment with the new approach. So clarifying your strategy and aligning the supporting elements must go hand in hand.

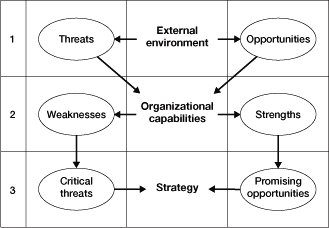

Viewing Organizations as Systems

If you hope to be effective as an organizational designer, you first have to understand what you are designing and how different design choices interact to affect performance. The point of departure involves understanding that organizations are open systems.

Open refers to the reality that organizations are profoundly influenced by their external environments. In the case of government organizations, mission and objectives are strongly shaped by the public environment, the demands of key constituencies, and the constraints imposed by laws and regulations. Closed systems are those where all the action happens inside and all the relevant variables can be controlled; they are obviously easier to design and manage. Every organization is an open system that strives to achieve closure by devising ways to control key elements of its external environment. Closure, however, never really happens with organizations; external influences always must play a vital role in organizational design.2

The systems part of open systems refers to the fact that, as illustrated in figure 7-1, organizations are made up of the five distinct design elements noted above, which interact. This has two major implications for your role as organizational architect. First, you can’t change one element without carefully thinking through the implications for the others. The most common approach to changing organizations focuses first on changing strategy and then on bringing structure into alignment. This can be done reasonably quickly and is fine, so far as it goes. But significant changes in strategy and structure almost certainly will necessitate corresponding changes in systems, skills, and even culture. If these are not explicitly thought through and implemented, the organization will be out of balance, frustrating the efforts of many. Often these misalignments will get resolved, but only after much frustration and loss in productivity. So if you are planning to change strategy and structure, think of it as phase one, with phase two being a similarly disciplined effort to work through the implications for systems and skills. Culture, the final element of organization architecture, will shift slowly in response to your efforts to alter behaviors and to change the other elements of organizational architecture.

FIGURE 7-1

Elements of organizational architecture

The second implication of the organizations-as-systems model is that it is possible to initiate significant change from any of the four “compass points” in figure 7-1. As mentioned, a common sequence involves changing the strategy first, the structure second, and then (hopefully) working through the implications for systems and skills. But it also is possible, and sometimes more effective, to initiate change by focusing on systems and skills. Process reengineering, for example, can be a powerful tool for streamlining organizations, so long as the implications for skills, culture, and structure are thought through. To the extent that organizational processes perform better, process reengineering can even have implications for strategy, because the organization is able to do things that it previously couldn’t.

There are many ongoing examples of public-sector organizations working to align structure and strategy. For example, the Internal Revenue Service had endeavored for over a decade to upgrade its data-processing capability to better review the almost 250 million federal tax returns it receives each year. For many reasons, not the least of which was constituent and political opposition to a more effective IRS, the effort did not succeed in developing and implementing such new technology. But then, in the mid-1990s, the IRS came under increasing pressure from Congress and others to depart from its traditional law-enforcement approach and move toward a more customer-oriented strategy.

Under the leadership of a new commissioner with extensive business experience, the IRS made large investments in communication technologies designed in large part to put its agents and technical-assistance personnel into closer contact with taxpayers. Combined with modernized auditing technology, the culture of the IRS—often referred to as the least popular agency of government—made a dramatic shift from a sole focus on enforcement to a mix of enforcement and customer assistance. While it still is not exactly beloved by taxpayers, the IRS today is a substantially different organization than it was, due largely to wise and well-targeted technology investments aimed at facilitating a new culture within this unpopular but critical government agency.3

It likewise is possible to initiate major changes by bringing people with new skills into the organization. The World Bank, for example, was once staffed almost exclusively with economists who, not surprisingly, believed in the power of economic models to determine how development should take place. Beginning in the mid-1990s, the leaders of the bank began a concerted effort to recruit other types of social scientists, such as anthropologists and sociologists, with their own models of how best to make development happen. Although it took time, this major shift in skill bases influenced the bank’s structure, the processes through which it dealt with developing countries, and ultimately its fundamental strategy.

Identifying Misalignments

Organizations can end up misaligned in many ways. The challenges faced by leaders of the Internal Revenue Service and the World Bank represented different kinds of organizational misalignment. One of your goals early in your transition should be to identify potential misalignments and then design a plan for correcting them. Common types of misalignments include the following:

• Structure and strategy misalignment. Elaine Trevino’s agency featured separate and often duplicative functions, inflexible and rigid staffing structures, differences in workload and productivity measurements, and poor internal transfer of information—all of which made it impossible for the agency to meet the secretary’s new mandate. The structure was working against the agency’s own future success and had to undergo dramatic realignment.

• Skills and strategy misalignment. Suppose you are heading a procurement office that has been tasked with acquiring stateof-the-art IT systems, which are integral to your agency’s strategy of improving constituent service. Your staff, however, has no experience in competitively acquiring such systems. In this case, your group’s skills do not match the requirements of the agency’s strategy, and new learning will be required to bring those skills into line. This kind of misalignment was a major hurdle the IRS had to overcome in redefining itself as being customer oriented.

• Systems and strategy misalignment. Imagine yourself as an information-technology manager in a large state humanservices agency. Recently passed welfare-reform legislation requires your agency to gather, disseminate, and, for the first time, interpret a new and elaborate array of state workforce data. Formerly, the agency’s information strategy was simply to collect and distribute data; now, however, agency leaders are required by the legislature to interpret the meaning of the statistical findings and to recommend policy initiatives to further the reform’s goal of reducing welfare rolls and increasing the employment rate of former welfare recipients. The management information system now in use is ten years old and cannot accommodate this new requirement because it is designed for the collection of data only and does not contain the software needed for analysis. Your organization’s systems cannot support your agency’s new mandated strategy. The World Bank faced this challenge; even after acquiring the new skills it felt were needed, it found that the existing delivery systems were inadequate and prevented the organization from carrying out its strategy.

To assess potential misalignments, the place to begin is strategy. If your organization’s strategy is a good match with its stated mission and goals, then it will most probably create the level of public value that is intended. If there is dissonance between strategy, mission, and goals, however, the strategy must change. But how? And what about structure? Does the structure support the strategy? If not, what structural change is necessary? If so, what about the organization’s systems, skills, and culture?

Crafting Strategy

In the introduction to this book we discussed the risks of entering a transition without a plan—we likened it to flying blind into a storm. This caution is as important for an organization undergoing change as it is for the new manager leading the change process. There is a necessary logic to organizational design that if ignored in haste or in disregard of the difficulties inherent in organizational change can make even the most well-intentioned efforts go awry.

First and foremost, be sure that you understand your agency’s larger goals and its strategy for achieving them, and that you and your boss agree on what part in it you and your group are expected to play. Then take a hard look at how your group is positioned with respect to that strategy. Crafting a well-thought-out and logical strategy for your group—one that defines not only what it will do but also what it will not do—will enable you to accomplish your objectives and contribute to the agency’s strategic goals as well.

In government, the fundamental strategic questions concern the mission of the organization, the interests of all the various stakeholders in your group’s performance, the statutory or regulatory constraints within which you must operate, the extant skills and capabilities of your group, and the availability of the resources you need. Use the following list to sketch out the basics of your group’s strategy:

• Mission. Businesses exist to create profits for their owners; government organizations exist to create public value. Accordingly, businesses use the bottom line as a common measure of success. The extreme variety of activities within government, however, yields major differences in the ways that public value is defined and measured from agency to agency. Accordingly, the strategy of a government organization will vary substantially depending on whether its mission is to provide services, to collect and analyze information, or to ensure compliance with laws and regulations. Customer orientation may be a desirable goal for the IRS, for example, but—if criminals and terrorists can be considered a lawenforcement agency’s customers—not for the FBI. So the starting point for evaluating and crafting strategy involves asking important questions: What is my organization’s mission? How is it expected to create public value? What does it take to ensure that this value gets created as efficiently and effectively as possible? Table 7-1 provides some examples of the ways in which governmental organizations create public value and the associated strategic imperatives. Note that your organization may actually have some units that do service delivery, some that do analysis and reporting, and some that do oversight and compliance. If this is the case, you should focus on identifying the missions and working through the strategy implications for each unit.

• Stakeholders. Who are the most important stakeholders influencing the way your group performs? In the public sector, these interests can run from the usual verticals of boss and subordinates (including public-employee unions), to the internal horizontals of critical support functions, and finally to the external environment of legislatures, budget and revenue authorities, constituents, and such influential public observers as the news media. Which of these have the most direct effect on your group’s performance? Which are most reliant on your success for their own success? Which must be consulted when developing your strategy?

• Constraints. In public-sector organizations, things like mission, goals, organizational structures, and agency performance metrics oftentimes are spelled out by law or regulation, and changing them, if they can be changed at all, often requires approval at many levels. In the case of Elaine Trevino’s agency, the new strategy promulgated by the secretary included a promise of some relief from constraining regulations. What latitude do you have to institute quick changes to your organization’s strategy, structure, systems, skills, and culture?

• Capabilities. What is your group good at, and what is it not so good at? On which strengths can you build a strategy for improvement? Which marginally performing capabilities must be improved? Which must be created or obtained from outside the group?

• Resources. In government, the acquisition of people, money, and space more often than not requires long lead time and must go through several layers of evaluation before a decision is made about them. Assuming that you are granted what you sought, actually acquiring them also takes a long time due to procurement and personnel system requirements. So, with the exception of when a new leader faces those relatively rare instances of a start-up or somewhat less rare instances of a turnaround, the immediate availability of resources is likely not to be something that should be counted on; making do with what you have will probably be the rule at the outset.

TABLE 7-1

Missions and strategic imperatives

| Type of public organization | Mission | Examples | Strategic imperatives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Service delivery | Provide specified services to the public as efficiently and effectively as possible. | Health care agencies, infrastructuredevelopment programs, financial services, information distribution, social service agencies | Efficient delivery, security and integrity, error minimization |

| Analysis and reporting | Provide policy makers with specified information and analysis. | Treasuries, budget authorities, intelligence agencies | Accuracy, timeliness, risk management |

| Oversight and compliance | Ensure that individuals and institutions comply with specified laws or regulations. | IRS, regulatory agencies, law enforcement | Effectiveness, fairness, crisis avoidance |

After reviewing the basic elements of your group’s strategy, the next step is to understand its logic. Again, history is important. Begin by reviewing whatever existing documentation you can get your hands on that describes your group’s mission and its past plans. Then break down the plans into their component parts—for example, goals and objectives, staffing patterns, budgets, workload measures, work processes, performance measures, and reporting systems. Do the various components of the plans complement each other? Is there a logical thread connecting them? For example, is there an obvious connection between workload measures, staffing patterns, and performance measures? If the group’s situation or mission is changing, are there plans in place to prepare the staff for the changes with new training or technologies? If the plans are good ones, these connections will be spotted easily.

Next, you should assess the existing strategy’s adequacy in terms of whether it promises to provide the resources the group will need over the next year or two. Does the existing strategy help support your agency’s goals? Will it empower your group to accomplish what it needs to do to succeed? To assess adequacy, first ask some probing questions of your boss and the staff about the sufficiency of resources available and the pragmatic probability of success under existing conditions. Then use the well-known SWOT method, to analyze the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats associated with the existing strategy. (See “SWOT Analysis.”) Is your organization flexible enough to respond to changing conditions? Does it rely too heavily on dubious assumptions about acquiring new resources? Is there an organizational requirement not being met that your group could fill? Is your group in danger of marginalization due to outmoded technologies or inefficient work processes? The IRS arguably faced these types of challenges.

Finally, you should assess how well the strategy has been implemented. No matter how coherent the strategy is, or how intelligently it addresses future requirements, if it has not been implemented well, all is for naught. Are the performance measurements specified in the strategy actually used to make day-to-day decisions? Are the major goals of the strategy in line with what senior management really cares about? Are people cooperating across specialties as required? Is there sufficient training to provide people with the skills they need?

Answers to these questions will tell you whether to change the group’s existing strategy or just the way it is being implemented. Chances are some modifications will be called for, so the next task is to decide how to do it.

Leading Strategic Change

Supposing that you discover major flaws in either the strategy or its implementation, can you radically change things without seriously disrupting your group’s ongoing performance? The answer depends on two factors: the STARS situation you are entering and your ability to persuade others and build support for your ideas.

Proposing significant changes to strategy is most difficult in realignment situations because you must convince people who believe they are performing well already that change is necessary. If, after evaluating the strategy in place, you conclude that the group is heading down the wrong path, your first job will be to persuade the boss and others that reexamining the strategy is necessary by asking such questions as: If we continue on this path, what might be the unintended consequences? Will the efforts needed to carry out this plan consume too many resources and crowd out more important goals? If, on the other hand, you conclude that the strategy will move your group in the right direction but neither fast enough nor far enough, the wisest course may be just to tweak it early on and plan for bigger changes later. For example, in the spirit of acquiring early wins to build your credibility, you might want to accelerate some training efforts or expedite the acquisition of a new technology. More fundamental changes should wait until you have completed your learning and built support among key stakeholders, many of whom will have to be convinced of the benefits and political feasibility of the changes you are proposing.

Altering the Structure

Once you have completed your assessment of your group’s strategy and made whatever modifications you concluded were needed, you can address the question of whether the existing organizational structure supports the new strategy. What exactly is structure? Simply put, it is the way your group organizes people and processes—including technologies—to support its strategy. Structure consists of the following elements:

• Units. How the people you manage are grouped, such as by function, service, constituency, geographical region, or some combination of those.

• Decision rights. Who is empowered to make various kinds of decisions and how much discretion they have.

• Reporting relationships. How people observe and control the way work is done.

• Performance-measurement and reward systems. What performance-evaluation metrics and reward systems are in place and what incentives they create for people to do and not do.

• Information-sharing and integration mechanisms. How individuals and groups in the organization share information to make decisions and integrate their efforts to achieve the mission and strategy.

Before deciding to reshape your group’s structure, carefully consider how these five elements interact. Does the way team members are grouped help achieve the goals? Who has the authority to make decisions? How is their work overseen? Are the kinds of achievements that matter most being measured and rewarded? Does information flow in the best way to facilitate efficient operations and decision making? Are there mechanisms in place to ensure that work in the “silos” gets integrated?

Unless you are in a start-up situation, where there is not an existing structure to assess, answering these basic questions about the way your organization is structured will position you to make correct decisions about changes that may be needed.

As you do this, keep in mind that there is no such thing as a perfect organization; every effort to design an organization necessitates making trade-offs. For example, leaders must always assess the tradeoff between efforts to create internal efficiencies through cost reduction, staff cuts, and organizational consolidations that, while they may improve work processes, may end up impairing the organization’s effectiveness in delivering the public services for which it was established. Ideally, an organization would be able to achieve all its various goals for efficiency and effectiveness, but in reality this is simply not possible. Public organizations often come under pressure to be “all things to all people.” This inevitably undermines efforts and erodes capabilities. The organization that tries to be good at everything ends up being excellent at nothing.

Thus your challenge is to find the right balance for your situation. Here are some common problems you might encounter as you consider structural changes:

• Is the team’s knowledge base too narrow, too broad, or too dated? When people of similar experience and training are grouped together, they can accumulate deep wells of expertise, but they also can become compartmentalized and isolated from the mainstream of core work processes. Similarly, groups with broad mixtures of skills may be more apt to be integrated with core processes, but they may do so at the cost of developing deeper experience. And if staff-development plans do not stress keeping current in the technologies and trends of the work, stagnation, with accompanying resistance to change, will take hold.

• Is employees’ decision-making scope too narrow or too broad? Although centralized decision making is usually the fastest method, it also usually excludes the advice and wisdom of others closer to the front lines who may be better equipped to make certain of those decisions. On the other hand, decision making spread out over a broad plane runs the risk of being placed in the hands of people who will make unwise calls because they do not understand the wider consequences of their choices. A good general rule is that decisions should be made by the people with the most relevant knowledge, so long as their incentives encourage them to do what is best for the organization.

• Are employees inappropriately rewarded? This is a major problem in public-sector organizations. Aside from the many pilot programs instituted over the years to experiment with pay-for-performance compensation plans, civil service rules tend to reward individual tenure more than performance and often work to encourage the pursuit of individual interests over group interests. Group awards are one possible solution to this problem because such awards tend to focus energy on team performance.

• Do reporting relationships filter information flow? Reporting relationships help observe and control the workings of your group, clarify responsibility, and encourage accountability. Strict hierarchical reporting relationships might make these tasks easier, but they can lead to a restrictive stovepipe, or vertical pattern, of information flow. More complex reporting arrangements like matrix structures can promote horizontal information sharing, but they can dangerously diffuse individual accountability and make performance measurement and reward difficult.

At Elaine Trevino’s agency, the strategy adopted to reposition the organization so that it could effectively compete against privatesector providers touched on all these issues. The combined goals of becoming customer focused, concentrating on cost control, loosening the boundaries between units so that resources could be pooled, redesigning compensation plans so that they encourage higher performance, and eliminating structural duplication moved the agency away from its historically stable structure toward the more adaptive model envisioned by the customer-based government initiative.

Aligning Key Systems

Systems, also referred to as “processes,” enable your group to transform information, materials, and knowledge into products or services that are essential for your larger organization as well as for other stakeholders. As with structures, you must begin by asking whether the processes currently in place support the strategy by enabling your group to meet or exceed the goals that it sets out.

The kind of processes required to carry out your strategy will vary with your goals. For example, if your major goals involve delivering existing high-quality products or services efficiently and reliably, there must be an intensive focus on developing processes that specify both the ends (productivity goals) and the means (methods, technologies, tools) in exquisite detail. But these same sorts of processes often have the effect of stymieing innovation. Therefore, if stimulating creativity is your major goal, you will need processes that focus more on defining ends and rigorously checking progress toward achieving them at key milestones, and less on controlling means. Performing a process analysis to map each system being employed within your group, identifying those that are most important to your strategy (your core processes), testing whether the related measurement and reward systems in place are appropriate, and identifying key bottlenecks is the first step toward achieving alignment between strategy and systems.

To evaluate the efficiency and effectiveness of each core process, you must examine four aspects:

• Productivity. Does the process efficiently transform knowledge, material, and labor into value?

• Timeliness. Does the process deliver the desired value in a timely manner?

• Reliability. Is the process sufficiently reliable, or does it frequently break down?

• Quality. Does the process deliver value in a way that consistently meets required quality standards?

When systems and structure jibe, the elements reinforce each other as well as the strategy. For example, a local government human-services agency structured so that trained teams work with specifically defined sectors of the constituent population (e.g., children, teens, young adults, parents, etc.) can incorporate a process by which information gathered by one team can be pooled and shared with all other teams. Such a formal information-sharing process can alert teams to others who might be facing similar or related situations, thereby elevating the performance of the agency as a whole. When systems and structure are at odds, such as when different teams compete for the same population using different approaches, they hamstring one another and subvert the larger group’s strategy.

How do you actually improve a core process? Begin with developing a process map as mentioned earlier—a straightforward diagram of exactly how the tasks in a particular process flow through the individuals and groups who handle them. An example of a process map for a supply unit servicing an organization’s material requirements is shown in figure 7-2.

FIGURE 7-2

Process mapping

The team should study the map to identify bottlenecks and problematic interfaces between the individuals responsible for each set of tasks. For example, errors or delays may occur when the supply unit communicates the need for urgency in filling a material order from a production unit but the message gets lost on its way to the fulfillment group—process failures are common during hand-offs of this kind. Once a problem has been identified as interfering with the reliability of the overall supply process, the team should develop ways to reduce its recurrence.

Process analysis stimulates collective learning. It helps the entire group understand exactly who does what, within and between units and groups, to carry out a particular process. As indicated in the process failure example discussed above, process mapping also sheds light on how problems arise.

A few words of caution. You most likely are managing a number of processes. If so, manage them as a portfolio. Do not try to introduce radical changes in more than a couple of core processes at a time. Your group is not likely to be able to absorb much change all at once. As mentioned earlier, for instance, do not immediately automate problematic processes, a tactic that rarely solves the real problem underlying process inefficiencies. Problems with processes usually center on miscommunication, confusion over expectations, and misunderstanding about how the agency works. Solving deeper problems will yield bigger benefits than simply resorting to automation.

Developing Group Skills

Does your staff have the skills and knowledge they need to perform your group’s core processes with excellence, and thus to support the strategy you have set? If not, the entire fragile architecture of your group could fall apart. A skills base is comprised of these four types of knowledge:

1. Individual expertise. Gained through training, education, and experience.

2. Rational knowledge. An understanding of how to work together to integrate individual knowledge to achieve specified goals.

3. Embedded knowledge. The core technologies on which your group’s performance depends, such as information systems and databases.

4. Meta-knowledge. The awareness of where to go to get critical information—for example, through internal support functions or external sources of relevant knowledge or expertise.

The overarching goal of assessing your group’s capabilities is to identify (1) critical gaps between needed and existing skills and knowledge and (2) underutilized resources, such as partially exploited technologies and unused expertise. Closing gaps and making better use of underutilized resources can by themselves produce substantial gains in performance and productivity.

To identify skills and knowledge gaps, first revisit your strategy and the core processes you identified. Ask yourself what mix of the four types of knowledge is needed to support your group’s core processes. Then assess your group’s existing skills, knowledge, and technologies. What gaps do you see? Which of them can be repaired quickly, and which will require more time?

To identify underutilized resources, search for individuals or groups in your unit who have performed much better than average. What has enabled them to do so? Do they enjoy resources—such as technologies, methods, materials, and support from key people—that could be exported to the rest of your unit? Have promising process-improvement ideas been tabled because of lack of interest or lack of resources?

Understanding the Culture

An organization’s culture will shape how it approaches new problems—problems not dealt with within the existing bureaucratic structure. Since bureaucratic institutions and their rules are static and only serve to shape the present, they tend to have little to offer about how a bureaucracy should face new challenges and problems. Accordingly, leaders who must address such changing conditions are likely to be most influenced by the organization’s cultural norms. In this regard, culture begins where rules end.

The central issue when seeking to understand the extant culture of a bureaucracy is drawing a distinction between its design, including rules and regulations, and its culture. As already noted, bureaucratic organizations are governed by written rules, and they are, to a large degree, defined by those rules because they serve to regulate behavior, distribute decision-making power, and establish the hierarchy of command that holds the bureaucratic organization together.

Organizational culture also is governed by rules, but not quite in the same way. Instead, it is governed by a set of unwritten norms that, though conditioned to some extent by organizational design, tend to be rooted in the ethos of the wider society to which the bureaucracy provides services. Norms, therefore, often are less easily discernable than the formal rules governing bureaucratic operations. This does not suggest that cultural norms are any less powerful than written rules when it comes to influencing the behavior of officials and others in the organization. To the contrary, culture often trumps rules, and that is why a new leader must understand it.

The culture that exists within a bureaucracy is shaped by internal and external forces. The internal forces are largely institutional, such as the organization’s structural design and the norms by which it operates. For example, a culture of collaboration is often missing in a tightly stovepiped organization. To understand the external forces, however, remember our discussion earlier in this chapter about viewing organizations as open systems and, accordingly, carefully consider the wider culture of the world beyond the organization’s boundaries.

Perhaps the most critical role played by any leader, and especially by those at an organization’s highest levels, is one of interpretation; the rules may provide a framework within which to act, but they do not by themselves dictate decisions. Leaders, as well as all those others on their influence maps, are social beings and act beyond the specifications of rules. They have prejudices, interests, and fears in the same way that any individual has, and these factors, together with the prevailing cultural norms of the wider society, will influence how people work within the rule-governed framework. Therefore, leaders who are faced with alignment challenges must consider formal organizational structure and cultural norms equally.

Avoiding Common Traps

As you take on the role of organizational architect, keep in mind that too many managers rely on simplistic fixes to address complicated organizational problems. Be alert to these all-too-common pitfalls:

• Trying to reorganize your way out of deeper problems. Overhauling your group’s structure in times of trouble can amount to straightening the deck chairs on the Titanic. Resist doing so until you understand whether restructuring will address the root causes of the problems. Otherwise, you may create new misalignments and have to backtrack, disrupting your group, lowering productivity, and damaging your credibility in the process.

• Creating structures that are too complex. This is a related trap. Although it may look good on paper to create a structure, such as a matrix, in which people in different units share accountability and in which creative tensions get worked out through those people’s interactions, too often the result is bureaucratic paralysis. Strive whenever possible for clear lines of accountability. Simplify the structure as much as possible without compromising core goals.

• Automating problematic processes. Automating your groups’ core processes may produce significant gains in productivity, quality, and reliability, but it is a mistake to simply speed up an existing process through technology if the process itself has serious underlying problems. Automation will not solve such problems and may even amplify them, making them even more difficult to remedy. Analyze and streamline processes first; then decide whether automation still makes sense.

• Making changes for change’s sake. Resist the temptation to tear down fences before you know why they were put up. It is important for new leaders to respect the past. Those who feel self-imposed pressure to put their stamp on the organization often make changes in strategy or structure before they really understand the situation they face.

• Overestimating your group’s capacity to absorb strategic shifts. It is easy to envision an ambitious new strategy. In practice, however, it is difficult for a group to change in response to large-scale strategic shifts. Advance incrementally if time allows. Focus on a vital few priorities. Make modest changes to your group’s strategy; experiment; and then progressively refine structure, systems, skills, and culture.

• Underestimating the importance of peripheral stakeholders. In government agencies, the number of stakeholders, their range of interests, and the variety of their perspectives are usually quite extensive. So avoid falling prey to believing that major structural changes can be made without doing important legwork—like coalition building or, at least, getting agreement among those stakeholders.

Conclusion

To be effective as a senior leader in government, you must be prepared to take on the role of organizational architect. This means cultivating your ability to observe and identify misalignments among strategy, structure, systems, skills, and culture. Draw on all this analysis to develop a plan for aligning your organization. If you are repeatedly frustrated in your efforts to get people to adopt more productive behaviors, step back and ask whether organizational misalignments might be creating problems.