A detailed account of the codes and ciphers of the Civil War of the United States of America can hardly be told without beginning with a bit of biography about the man who became the first signal officer in history and the first Chief Signal Officer of the United States Army, Albert J. Myer, the man in whose memory that lovely little U.S. Army post adjacent to Arlington Cemetery was named. Myer was born on 20 September 1827, and after an apprenticeship in the then quite new science of electric telegraphy he entered Hobart College, Geneva, New York, from which he was graduated in 1847. From early youth he had exhibited a predilection for artistic and scientific studies, and upon leaving Hobart he entered Buffalo Medical College, receiving the M.D. degree four years later. His graduation thesis, "A Sign Language for Deaf Mutes," contained the germ of the idea he was to develop several years later, when in 1854 he was commissioned a first lieutenant in the regular army, made an assistant surgeon, and ordered to New Mexico for duty. He had plenty of time at this faraway outpost to think about developing an efficient system of military "aerial telegraphy," which was what visual signaling was then called. I emphasize the word "system" because, strange to say, although instances of the use of lights and other visual signals can be found throughout the history of warfare, and their use between ships at sea had been practiced by mariners for centuries, down to the middle of the nineteenth century surprisingly little progress had been made in developing methods and instruments for the systematic exchange of military information and instructions by means of signals of any kind. Morse's practical system of electric telegraphy, developed in the years 1832–35, served to focus attention within the military upon systems and methods of intercommunication by means of both visual and electrical signals. In the years immediately preceding the Civil War, the U.S. Army took steps to introduce and to develop a system of visual signaling for general use in the field. It was Assistant Surgeon Myer who furnished the initiative in this matter.

In 1856, two years after he was commissioned assistant surgeon, Myer drafted a memorandum on a new system of visual signaling and obtained a patent on it. Two years later, a board was appointed by the War Department to study Myer's system. It is interesting to note that one of the officers who served as an assistant to Myer in demonstrating his system before the board was a Lieutenant E.P. Alexander, Corps of Engineers. We shall hear more about him presently, but at the moment I will say that on the outbreak of war, Alexander organized the Confederate Signal Corps. After some successful demonstrations by Myer and his assistants, the War Department fostered a bill in Congress, which gave its approval to his ideas. But what is more to the point, Congress appropriated an initial amount of $2,000 to enable the Army and the War Department to develop the system. The money, as stated in the act, was to be used "for manufacture or purchase of apparatus and equipment for field signaling." The act also contained another provision: it authorized the appointment on the Army staff of one signal officer with the rank, pay, and allowances of a major of cavalry. On 2 July 1860, "Assistant Surgeon Albert J. Myer (was appointed) to be Signal Officer, with the rank of Major, 27 June 1860, to fill an original vacancy," and two weeks later Major Myer was ordered to report to the commanding general of the Department of New Mexico for signaling duty. The War Department also directed that two officers be detailed as his assistants. During a several months' campaign against hostile Navajos, an extensive test of Myer's new system, using both flags and torches, was conducted with much success. In October 1860, a Lieutenant J.E.B. Stuart, later to become famous as a Confederate cavalry leader, tendered his services to aid in signal instruction.

Less than a year after Major Myer was appointed as the first and, at that time, the only signal officer of the U.S. Army, Fort Sumter was attacked, and after a thirty-six-hour bombardment, it surrendered. The bloody four-year war between the North and the South had begun. The date was 14 April 1861. Myer's system of aerial telegraphy was soon to undergo its real baptism under fire, rather than by fire. But with the outbreak of war, another new system of military signal communication, signaling by the electric telegraph, began to undergo its first thorough test in combat operations. This in itself is very important in the history of cryptology. But far more significant in that history is a fact I mentioned at the close of the last lecture, viz, that for the first time in the conduct of organized warfare, rapid and secret military communications on a large scale became practicable, because cryptology and electric telegraphy were now to be joined in lasting wedlock. For when the war began, the electric telegraph had been in use for less than a quarter of a century. Although the first use of electric telegraphy in military operations was in the Crimean War in Europe (1854–56), its employment was restricted to communications exchanged among headquarters of the Allies, and some observers were very doubtful about its utility even for this limited usage. It may also be noted that in the annals of that war there is no record of the employment of electric telegraphy together with means for protecting the messages against their interception and solution by the enemy.

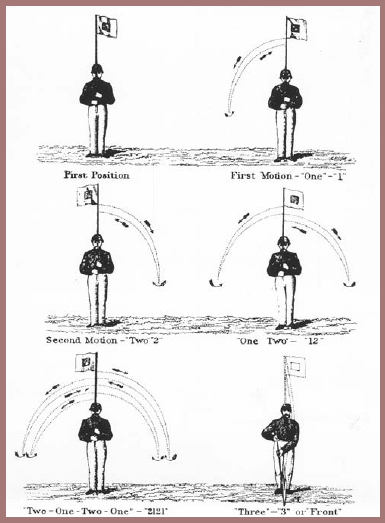

On the Union side in the Civil War, military signal operations began with Major Myer's arrival in Washington on 3 June 1861. His basic equipment consisted of kits containing a white flag with a red square in the center for use against a dark background, a red flag with a white square for use against a light background, and torches for night use. It is interesting to note that these are the elements that make up the familiar insignia of our Army Signal Corps. The most pressing need that faced Major Myer was to get officers and men detailed to him wherever signals might be required, and to train them in what had come to be called the "wig-wag system," the motions of which are depicted in figure 53. This training included learning something about codes and ciphers and gaining experience in their use.

But there was still no such separate entity as a Signal Corps of the Army. Officers and enlisted men were merely detailed for service with Major Myer for signaling duty. It was not until two years after the war started that the Signal Corps was officially established and organized as a separate branch of the Army, by appropriate congressional action.

In the meantime, another signaling organization was coming into being – an organization that was an outgrowth of the government's taking over control of the commercial telegraph companies in the United States on 25 February 1862. There were only three: the American, the Western Union, and the Southwestern. The telegraph lines generally followed the right-of-way of the railroads. The then secretary of war, Simon Cameron, sought the aid of Thomas A. Scott of the Pennsylvania Railroad, who brought some of his men to Washington for railroad and telegraphic duties with the federal government. From a nucleus of four young telegraph operators grew a rather large military telegraph organization that was not given formal status until on 28 October 1861 President Lincoln gave Secretary Cameron authority to set up a "U.S. Military Telegraph Department" under a man named Anson Stager, who, as a general superintendent of the Western Union, was called to Washington, commissioned a captain (later a colonel) in the Quartermaster Corps, and made superintendent of the Military Telegraph Department. Only about a dozen of the members of the department became commissioned officers, and they were made officers so that they could receive and disburse funds and property; all the rest were civilians. The U.S. Military Telegraph "Corps," as it soon came to be designated, without warrant, was technically under Quartermaster General Meigs, but for all practical purposes it was under the immediate and direct control of the secretary of war, a situation admittedly acceptable to Meigs. There were now two organizations for signaling in the Army, and it has hardly to be expected that no difficulties would ensue from the duality. In fact, the difficulties began very soon, as can be noted in the following extract from a lecture before the Washington Civil War Round Table, early in 1954, by Dr. George R. Thompson, Chief of the Historical Division of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer of the U.S. Army:

The first need for military signals arose at the important Federal fortress in the lower Chesapeake Bay at Fort Monroe. Early in June, Myer arrived there, obtained a detail of officers and men and began schooling them. Soon his pupils were wig-wagging messages from a small boat, directing fire of Union batteries located on an islet in Hampton Roads against Confederate fortifications near Norfolk. Very soon, too, Myer began encountering trouble with commercial wire telegraphers in the area. General Ben Butler, commanding the Federal Department in southeast Virginia, ordered that wire telegraph facilities and their civilian workers be placed under the signal officer. The civilians, proud and jealous of their skills in electrical magic, objected in no uncertain terms and shortly an order arrived from the Secretary of War himself who countermanded Butler's instructions. The Army signal officer was to keep hands off the civilian telegraph even when it served the Army.

I have purposely selected this extract from Dr. Thompson's presentation because in it we can clearly hear the first rumblings of that lengthy and acrimonious feud between two signaling organizations whose uncoordinated operations and rivalry greatly reduced the efficiency of all signaling operations of the Federal army. As already indicated, one of these organizations was the U.S. Military Telegraph "Corps," hereinafter abbreviated as the USMTC, a civilian organization that operated the existing commercial telegraph systems for the War Department, under the direct supervision of the secretary of war, Edwin M. Stanton. The other organization was, of course, the infant Signal Corps of the United States Army, which was not yet even established as a separate branch, whereas the USMTC had been established in October 1861, as noted above. Indeed, the Signal Corps had to wait until March 1863, two years after the outbreak of war, before being established officially. In this connection it should be noted that the Confederate Signal Corps had been established a full year earlier, in April 1862. Until then, as I've said before, for signaling duty on both sides, there were only officers who were individually and specifically detailed for such duty from other branches of the respective armies of the North and the South. Trouble between the USMTC and the Signal Corps of the Union army began when the Signal Corps became interested in signaling by electric telegraphy and began to acquire facilities therefor.

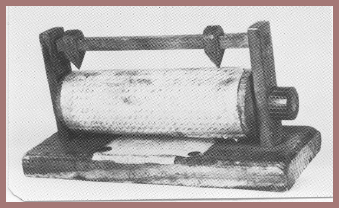

As early as June 1861, Chief Signal Officer Myer had initiated action toward acquiring or obtaining electrical telegraph facilities for use in the field, but with one exception nothing happened. The exception was the episode in the military department in southeast Virginia, commanded by General Benjamin Butler, an episode that clearly foreshadowed the future road for the Signal Corps in regard to electrical signaling: the road was to be closed and barred. In August 1861 Colonel Myer tried again, and in November of the same year he recommended in his annual report that $30,000 be appropriated to establish an electric signaling branch in the Signal Corps. The proposal failed to meet the approval of the secretary of war. One telegraph train, however, that had been ordered by Myer many months before, was delivered in January 1862. The train was tried out in an experimental fashion, and under considerable difficulties, the most disheartening of which was the active opposition of persons of Washington, particularly the secretary of war. So, for practically the whole of the first two years of the war, signal officers on the Northern side had neither electrical telegraph facilities nor Morse operators – they had to rely entirely on the wig-wag system. However, by the middle of 1863 there were thirty "flying telegraph" trains in use in the Federal army. Here's a picture (fig. 54) of such a train. The normal length of field telegraph lines was five to eight miles, though in some cases the instruments had worked at distances as great as twenty miles. But even before the Signal Corps began to acquire these facilities, there had been agitation to have them, as well as their Signal Corps operating personnel, all turned over to the USMTC, which had grown into a tightly knit organization of over 1,000 men and had become very influential in Washington, especially by virtue of its support from Secretary of War Stanton. As a consequence, the USMTC had its way. In the fall of 1863, it took over all the electric telegraph facilities and telegraph operators of the Signal Corps. Colonel Myer sadly wrote: "With the loss of its electrical lines the Signal Corps was crippled."

So now there were two competing signal organizations on the Northern side: the U.S. Army's Signal Corps, which was composed entirely of military personnel with no electric telegraph facilities (but was equipped with means for visual signaling), and the USMTC, which was not a part of the Army, being staffed almost entirely with civilians, and that had electric telegraph facilities and skilled Morse operators (but no means or responsibilities for visual signaling or "aerial telegraphy" that, of course, was old stuff). "Electric telegraphy" was now the thing. The USMTC had no desire to share electric telegraphy with the Signal Corps, a determination in which it was most ably assisted by Secretary of War Stanton, for reasons that fall outside the scope of the present lecture.

However, from a technical point of view it is worth going into this rivalry just a bit, if only to note that the personnel of both organizations, the military and the civilian, were not merely signalmen and telegraph operators: they served also as cryptographers and were therefore entrusted with the necessary cipher books and cipher keys. Because of this, they naturally became privy to the important secrets conveyed in cryptographic communications, and they therefore enjoyed status as VIPs. This was particularly true of members of the USMTC, because they, and only they, were authorized to be custodians and users of the cipher books. Not even the commanders of the units they served had access to them. For instance, on the one and only occasion when General Grant forced his cipher operator, a civilian named Beckwith, to turn over the current cipher book to a colonel on Grant's staff, Beckwith was immediately discharged by the secretary of war, and Grant was reprimanded. A few days later Grant apologized, and Beckwith was restored to his position. But Grant never again demanded the cipher book held by his telegraph operator.

Figure 54. A drawing from Myer's Manual of Signals illustrating the field, or flying, telegraph. It shows the wagon with batteries and instruments. The wire (in this case presumably bare copper, since it is being strung on insulators on poles) is being run out from a reel carried by two men. The linemen are using a crowbar to open holes to receive the lance poles. Myer estimated that 2 ½ miles of such wire line could put up in an hour.

The Grant-Beckwith affair alone is sufficient to indicate the lengths to which Secretary of War Stanton went to retain control over the USMTC, including its cipher operators and its cipher books. In fact, so strong a position did he take that on 10 November 1863, following a disagreement over who should operate and control all the military telegraph lines, Myer, by then full colonel and bearing the imposing title "Chief Signal Officer of the United States Army," a title he had enjoyed for only two months, was peremptorily relieved from that position and put on the shelf. Not long afterward, and for a similar reason, Myer's successor, Lieutenant Colonel Nicodemus, was likewise summarily relieved as Chief Signal Officer by Secretary Stanton; indeed, he was not only removed from that position – he was "dismissed from the Service." Stanton gave "phony" reasons for dismissing Colonel Nicodemus, but I am glad to say that the latter was restored his commission in March 1865 by direction of the president; also by direction of the president, Colonel Myer was restored to his position as Chief Signal Officer of the U.S. Army on 25 February 1867.

When Colonel Myer was relieved from duty as Chief Signal Officer in November 1863, he was ordered to Cairo, Illinois, to await orders for a new assignment. Very soon thereafter he was either designated (or he may have himself decided) to prepare a field manual on signaling, and there soon appeared, with a prefatory note dated January 1864, a pamphlet of 148 pages, a copy of which is now in the Rare Book Room of the Library of Congress. The title page reads as follows:

A Manual of Signals: for the use of signal officers in the field. By Col. Albert J. Myer, Signal Officer of the Army, Washington, D.C., 1864.

Even in this first edition, printed on an Army press, Myer devoted nine pages to a reprint of an article from Harper's Weekly entitled "Curiosities of Cipher," and in the second edition, 1866, he expanded the section on cryptography to sixty pages. More editions followed, and I think we may well say that Myer's Manual, in its several editions, was the pioneer American text on military signaling. But I'm sorry to say that as regards cryptology it was rather a poor thing. Poe had done better twenty years before that in his essay entitled "A few words on secret writing."

Because of its historic nature, you may like to see what Myer's original "wig-wag code" was like. It was called a "two element code" because it employed only two digits, 1 and 2, in permutations of 1, 2, 3 and 4 groups. For example, A was represented by the permutation 22; B by 2122; and C, by 121, etc. In flag signaling, a "1" was indicated by a motion to the left, and a "2" by a motion to the right. Later these motions were reversed, for reasons that must have been good then but are now not obvious.[4] Myer's two-element code, which continued to be used until 1912, is shown in the figure below.

We must turn our attention now to the situation as regards the organization for signaling in the Confederate Army. It is of considerable interest to note that in the first great engagement of the war, the first Bull Run battle, the Confederate signal officer was that young lieutenant, E.P. Alexander, who had assisted in demonstrating the wig-wag system before a board appointed by the War Department to study Myer's system. Alexander, now a captain in grey, used Myer's system during the battle, which ended in disaster for the Union forces; it is said that Alexander's contribution by effective signaling was an important factor in the Confederate victory. Dr. Thompson, whom I have quoted before, says of this battle:

Thus the fortunes of war in this battle saw Myer's system of signals succeed, ironically, on the side hostile to Myer. Because of general unpreparedness and also some disinterest and ignorance, the North has neither wig-wag nor balloon observations.

The only communication system that succeeded in signal work for the Union army was the infant USMTC. But the Confederate system under Alexander, off to a good start at Bull Run, throughout the war operated with both visual and electric telegraphy, and the Confederates thought highly enough of their signal service to establish it on an official basis on 19 April 1862, less than a year after that battle. Thus, although the Confederate Signal Corps never became a distinct and independent branch of the Army as did the Union Signal Corps, it received much earlier recognition from the Confederate government than did the Signal Corps of the federal government. Again quoting Dr. Thompson:

The Confederate Signal Corps was thus established nearly a year earlier than its Federal counterpart. It was nearly as large, numbering some 1,500, most of the number, however, serving on detail. The Confederate Signal Corps used Myer's system of flags and torches. The men were trained in wire telegraph, too, and impressed wire facilities as needed. But there was nothing in Richmond or in the field comparable to the extensive and tightly controlled civilian military telegraph organization which Secretary Stanton ruled with an iron hand from Washington.

We come now to the codes and ciphers used by both sides in the war, and in doing so we must consider that on the Union side, there were, as I have indicated, two separate organizations for signal communications, one for visual signaling, the other for electric. We should therefore not be too astonished to find that the cryptosystems used by the two competing organizations were different. On the other hand, on the Confederate side, as just noted, there was only one organization for signal communications, the Signal Corps of the Confederate States Army, that used both visual and electric telegraphy, the latter facilities being taken over and employed when and where they were available. There were reasons for this marked difference between the way in which the Union and the Confederate signal operations were organized and administered, but I do not wish to go into them now. One reason, strange to say, had to do with the difference between the cryptocommunication arrangements in the Union and the Confederate armies.

We will discuss the cryptosystems used by both the Federal Signal Corps first and then those of the Confederate Signal Corps. Since both corps used visual signals as their primary means, we find them employing Myer's visual-signaling code shown above. At first both sides sent unenciphered messages; but soon after learning that their signals were being intercepted and read by the enemy, each side decided to do something to protect its messages. Initially both decided on the same artifice, viz, changing the visual signaling equivalents for the letters of the alphabet, so that, for instance, "22" was not always "A," etc. This sort of changing-about of values soon became impractical, since it prevented memorizing the wig-wag equivalents once and for all. The difficulty in the Union army's Signal Corps was solved by the introduction into usage of a cipher disk invented by Myer himself. A full description of the disk in its various embodiments will be found in Myer's Manual, but here's a picture of three forms of it. You can see how readily the visual wig-wag equivalents for letters, figures, etc., can be changed according to some prearranged indicator for juxtaposing concentric disks. In my figure 55, the top left disks (fig. 1 of Myer's Plate XXVI) show that the letter A is represented by 112, B by 22, etc. By moving the two circles to a different juxtaposition, a new set of equivalents will be established. Of course, if the setting is kept fixed for a whole message, the encipherment is strictly monoalphabetic; but Myer recommends changing the setting in the middle of the message or, more specifically, at the end of each word, thus producing a sort of polyalphabetic cipher that would delay solution a bit. An alternative way, Myer states, would be to use what he called a "countersign word," but that we call a key word, each letter of which would determine the setting of the disk or for a single word or for two consecutive words, etc. Myer apparently did not realize that retaining or showing externally, that is, in the cipher text, the lengths of the words of the plain text very seriously impairs the security of the cipher message. A bit later we shall discuss the security afforded by the Myer disk in actual practice.

In the Confederate Signal Corps, the system used for encipherment of visual signals was apparently the same as that used for enciphering telegraphic messages, and we shall soon see what it was. Although Myer's cipher disk was captured a number of times, it was apparently disdained by the Confederates, who preferred to use a wholly different type of device, as will be described presently, for both visual and electric telegraphy.

So much for the cryptosystems used in connection with visual signals by the Signal Corps of both the North and the South, systems that we may designate as "tactical ciphers." We come now to the systems used for what we may call "strategic ciphers," because the latter were usually exchanged between the seat of government and field commanders, or among the latter. In the case of these communications, the cryptosystems employed by each side were quite different.

On the Northern side, the USMTC used a system based upon what we now call transposition, but in contemporary accounts they were called "route ciphers," and that name has stuck. The designation isn't too bad, because the processes of encipherment and decipherment, though dealing not with the individual letters of the message but with entire words, involves following the prescribed routes in a diagram in which the message is written. I know no simpler or more succinct description of the route cipher than that given by one of the USMTC operators, J.E. O'Brien, in an article in Century Magazine, XXXVIII, September 1889, entitled "Telegraphing in Battle":

The principle of the cipher consisted in writing a message with an equal number of words in each line, then copying the words up and down the columns by various routes, throwing in an extra word at the end of each column, and substituting other words for important names and verbs.

A more detailed description in modern technical terms would be as follows: a system in which in encipherment the words of the plaintext message are inscribed within a matrix of a specified number of tows and columns, inscribing the words within the matrix from left. to right, in successive lines and rows downward as in ordinary writing, and taking the words out of the matrix, that is, transcribing them, according to a prearranged route to form the cipher message. The specific routes to be followed were set forth in numbered booklets, each being labeled "War Department Cipher" followed by a number. In referring to them hereinafter, I shall use the terms "cipher books" or, sometimes more simply, the term "ciphers," although the cryptosystem involves both cipher and code processes. It is true that the basic principle of the system, that of transposition, makes the system technically a cipher system as defined in our modern terminology; but the use of "arbitraries," as they were called, that is, words arbitrarily assigned to represent the names of persons, geographic points, important nouns, and verbs, etc., makes the system technically a code system as defined in our modern terminology.

There were in all about a dozen cipher books used by the USMTC throughout the war. For the most part they were employed consecutively, but it seems that sometimes two different ones were employed concurrently. They contained not only the specific routes to be used but also indicators for the routes and for the sizes of the matrices; and, of course, there were lists of code words, with their meanings. These route ciphers were supposed to have been the invention of Anson Stager, whom I have mentioned before in connection with the establishment of the USMTC, and who is said to have first devised such ciphers for General McClellan's use in West Virginia in the summer of 1861, before McClellan came to Washington to assume command of the Army of the Potomac.

Anson Stager and many others thought that he was the original inventor of the system, but such a belief was quite in error because word-transposition methods similar to Stager's were in use hundreds of years before his time. For instance, in 1685, in an unsuccessful attempt to invade Scotland, in a conspiracy to set the Duke of Monmouth on the throne, Archibald Campbell, 9th Earl of Argyll, suffered an unfortunate "accident": he was taken prisoner and beheaded by order of James the Second. The communications of the poor Earl were not secure, and when they fell into government hands they were soon deciphered. The method Argyll used was that of word transposition, and if you are interested in reading a contemporary account of how it was solved, look on pages 56–59 of that little book I mentioned before as being one of the very first books in English dealing with the subject of cryptology, that by James Falconer, entitled Cryptomenysis Patefacta: Or the Art of Secret Information Disclosed Without a Key, published in London in 1685. There you will find the progenitor of the route ciphers employed by the USMTC, 180 years after Argyll's abortive rebellion.

The route ciphers employed by the USMTC are fully described in a book entitled The Military Telegraph during the Civil War, by Colonel William R. Plum, published in Chicago in 1882. I think Plum's description of them is of considerable interest, and I recommend his book to those of you who may wish to learn more about them, but they are pretty much all alike. If I show you one example of an actual message and explain its encipherment and decipherment, I will have covered practically the entire gamut of the route ciphers used by the USMTC, so basically very simple and uniform were they. And yet, believe it or not, legend has it that the Southern signalmen were unable to solve any of the messages transmitted by the USMTC. This longheld legend I find hard to believe. In all the descriptions I have encountered in the literature, not one of them, save the one quoted above from O'Brien, tries to make these ciphers as simple as they really were; somehow, it seems to me, a subconscious realization on the part of Northern writers, usually ex-USMTC operators, of the system's simplicity prevented a presentation that would clearly show how utterly devoid it was of the degree of sophistication one would be warranted in expecting in the secret communications of a great modern army in the decade 1860–1870, three hundred years after the birth of modern cryptography in the papal states of Italy.

Let us take the plain text of a message that Plum (p. 58) used in an example of the procedure in encipherment. The cipher book involved is No.4, and I happen to have a copy of it so we can easily check Plum's work. Here's the message to be enciphered:

Washington, D.C. July 15, 1863

For Simon Cameron

I would give much to be relieved of the impression that Meade, Couch, Smith and all, since the battle of Gettysburg, have striven only to get the enemy over the river without another fight. Please tell me if you know who was the one corps commander who was for fighting, in the council of war on Sunday night.

(Signed) A. Lincoln

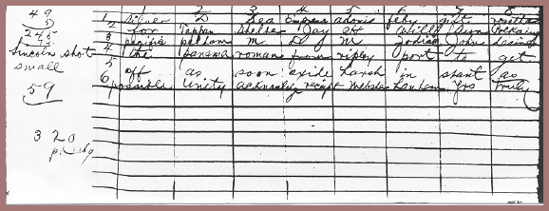

Plum shows the word-for-word encipherment in a matrix of seven columns and eleven rows.[5] He fails to tell us why a matrix of those dimensions was selected; presumably the selection was made at random, which was certainly permissible. (See fig. 56.)

Note the seven "nulls" (nonsignificant, or "blind" words) at the tops and bottoms of certain columns, these being added to the cipher text in order to confuse a would-be decipherer. At least that was the theory, but how effective this subterfuge was can be surmised, once it became known that employing nulls was the usual practice. Note also the two nulls (bless and him) at the end of the last line to complete that line of the matrix. Words in italics are "arbitraries" or code words.

The cipher message is then copied down following the route prescribed by the indicator "BLONDE," as given on page 7 of Cipher Book No.4 for a message of eleven lines. The indicator could have also been "LINIMENT ."

To explain the diagram at the top of figure 57, I will show you the "Directions for Use" that appear on the reverse side of the title page of "War Department Cipher No.4," because I'm afraid you wouldn't believe me if I merely told you what they say. In figure 58 is a picture of the title page, and I follow it with figure 59, a photograph of what's on its reverse.

Do you imagine that the chap who was responsible for getting this cipher book approved ever thought about what he was doing when he caused those "Directions for Use" to be printed? It doesn't seem possible. All he would have had to ask himself was, "Why put this piece of information in the book itself? Cipher books before this have been captured. Suppose this one falls into enemy hands; can't he read, too, and at once learn about the intended deception? Why go to all the trouble of including "phony" routes, anyway? If the book doesn't fall into enemy hands, what good are the "phony" routes anyway? Why not just indicate the routes in a straightforward manner, as had been done before? Thus: "Up the 6th column (since "6" is the first number at the left of the diagram), down the 3rd, up the 5th, down the 7th. up the 1st, down the 4th, and down the 2nd." This matter is so incredibly fatuous that it is hard to understand how sensible men – and they were sensible – could be so illogical in their thinking processes. But there the "Directions for Use" stand for all the world to see and to judge.

Now for the transposition step. The indicator "BI.ONDE" signifies a matrix of seven columns and eleven rows, with the route set forth above, viz, up the 6th column, down the 3rd, etc., so that the cipher text with a "phony" address and signature,[6] becomes as follows:

Washington, D.C

TO: A. HARPER CALDWELL, Cipher Operator, Army of the Potomac:

Blonde bless of who no optic to get and impression I Madison square Brown cammer Toby ax the have turnip me Harry bitch rustle silk Adrian counsel locust you another only of children serenade flea Knox County for wood that awl ties get hound who was war him suicide on for was please village large bat Bunyan give sigh incubus heavy Norris on trammeled cat knit striven without if Madrid quail upright martyr Stewart man much bear since ass skeleton tell the oppressing Tyler monkey.

Note that the text begins with the indicator "BLONDE." In decipherment the steps are simply reversed. The indicator tells which size matrix to outline; the words beginning "bless of who no optic. . ." are inscribed within the matrix: up the 6th column; then omitting the "check word" or "null" (which in this case is the word "square") down the 3rd column, etc. The final result should correspond to what is shown in figure 56. There then follows the step of interpreting orthographic deviations, such as interpreting "sigh," "man," "cammer," and "on" as Simon Cameron; the word "wood" for "would," etc. The final step reproduces the original plain text.

Save for one exception, all the route ciphers used by the USMTC conformed to this basic pattern. The things that changed from one cipher book to the next were the indicators for the dimensions of the matrices and for the routes, and the "arbitraries" or code equivalents for the various items comprising the "vocabulary," the number of them increasing from one edition to the next, just as might be expected. The sole exception to this basic pattern is to be seen in Cipher Book No, 9 and on only one page of the book. I will show you that page. (See fig. 60.)

What we have here is a deviation from the straightforward route transposition, "up the column, . . .down the. . . column," etc. By introducing one diagonal path in the route (the 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th words in a message of five columns, and the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 6th words in a message of six columns) the simple up and down route no longer holds true. The words on the diagonal interrupt the normal up and down paths and introduce complexities in the method. In fact, the complexities seemed to be a bit too much for the USMTC cipher operators, because, as far as available records show, these complicated routes were never used.

I now wish to make a number of general and a few specific comments on Plum's description of the cryptosystems used by the USMTC.

First, we have learned that although Anson Stager has been credited with inventing the type of cipher under consideration in this study, he was anticipated in the invention by about 200 years. Also, he is given the lion's share of the credit for devising those ciphers, although he did have a number of collaborators. Plum names four of them, presumably because he thought them worthy of being singled out for particular attention. Plum and others tell us that copies of messages handled by the USMTC were sometimes intercepted by the enemy but not solved. He cites no authority for this last statement, merely saying that such intercepts were published in the newspapers of the Confederacy with the hope that somebody would come up with their solution. And it may be noted that none of the Confederate accounts of war activities cite instances of the solution of intercepted USMTC messages, although there are plenty of citations of instances of interception and solution of enciphered visual transmissions of the Federal army's signal corps.

Plum states that twelve different cipher books were employed by the Telegraph Corps, but I think there were actually only eleven. The first one was not numbered, and this is good evidence that a long war was not expected. This first cipher book had sixteen printed pages. But for some reason, now impossible to fathom, the sequence of numbered books thereafter was as follows: Nos. 6 and 7, which were much like the first (unnumbered) one; then came Nos. 12, 9, 10 – in that strange order; then came Nos. 1 and 2; finally came Nos. 3, 4, and 5. (Apparently there was no No.8 or No. 11 – at least they are never mentioned.) It would be ridiculous to think that the irregularity in numbering the successive books was for the purpose of communication security, but there are other things about the books and the cryptosystem that appear equally silly. There may have been good reasons for the erratic numbering of the books, but if so, what they were is now unknown. Plum states that No.4, the last one used in the war, was placed into effect on 23 March 1865, and that it and all other ciphers were discarded on 20 June 1865. However, as noted, there was a No.5, which Plum says was given a limited distribution. I have a copy of it, but whether it was actually put into use I do not know. Like No.4, it had forty pages. About twenty copies were sent to certain members of the USMTC, scattered among twelve states; and, of course, Washington must have had at least one copy.

We may assume with a fair amount of certainty that the first (the unnumbered) cipher book used by the USMTC was merely an elaboration of the one Stager produced for the communications of the governors of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois, and of which a copy is given by only one of the writers who have told us about these ciphers, namely, David H. Bates. Bates, in his series of articles entitled "Lincoln in the Telegraph Office" (The Century Magazine, Vol. LXXIV, Nos 1–5, May-September, 1907)[7] shows a facsimile thereof (p. 292, June 1907 issue), and I have had as good a reproduction made of it as possible from rather poor photographic facsimile. The foregoing cipher is the prototype upon which all subsequent cipher books were based, the first of the War Department series being the one shown by Plum.

When these ciphers came into use, it was not the practice to misspell certain words intentionally; but as the members of the USMTC (who, as I've told you, served not only as telegraph operators but also as cipher clerks) developed expertness, the practice of using nonstandard orthography was frequently employed to make solution of messages more difficult. You have already seen examples of this practice, and one can find hundreds of other examples of this sort of artifice. Then, further to increase security, more and more code equivalents were added to represent such things as ordinal and cardinal numbers, months of the year, days of the week, hours of the day, punctuation, etc. As a last step, additional code equivalents for frequently used words and phrases were introduced. One good example of two typical pages from one of these books will characterize them all.

You will notice that the code equivalents are printed, but their meanings are written in by hand. This was usually the case, and the reason is obvious: for economy in printing costs, because the printed code equivalents of plaintext items in cipher books belonging to the same series are identical; only their meanings change from one book to another; and, of course, the transposition routes, their indicators, and other variables change from one book to another. I am fortunate in having six of these cipher books in my private collection, so that comparisons among them are readily made. The first feature to be noted is that the code equivalents are all good English dictionary words (or proper nouns) of not less than three nor more than seven (rarely eight) letters. A careful scrutiny shows that in the early editions the code equivalents are such as not very likely to appear as words in the plaintext messages; but in the later editions, beginning with No. 12, more than 50 percent of the words used as code equivalents are such as might well appear in the plain text of messages. For example, words such as AID, ALL, ARMY, ARTILLERY, JUNCTION, CONFEDERATE, etc., baptismal names of persons, and names of cities, rivers, bays, etc., appear as code equivalents. Among names used as code equivalents are SHERMAN, LINCOLN, THOMAS, STANTON, and those of many other prominent officers and officials of the Union army and the federal government, as well as of the Confederate army and government; and, even more intriguing, such names were employed as indicators for the number of columns and the routes used – the so-called "Commencement Words." It would seem that names and words such as those I've mentioned might occasionally have brought about instances where difficulty in deciphering messages arose from this source of confusion, but the literature doesn't mention them. I think you already realize why such commonly used proper names and words were not excluded. There was, indeed, method in this madness.

But what is indeed astonishing to note is that in the later editions of these cipher books, in a great majority of cases, the words used as "arbitraries" differ from one another by at least two letters (for example, LADY and LAMB, LARK and LAWN, ALBA and ASIA, LOCK and WICK, MILK and MINT) or by more than two (for example, MYRTLE and MYSTIC, CARBON and CANCER, ANDES and ATLAS). One has to search for cases in which two words differ by only one letter, but they can be found if you search long enough for them, for example, QUINCY and QUINCE, PINE and PIKE, NOSE and ROSE. Often there are words with the same initial trigraph or tetragraph, but then the rest of the letters are such that errors of transmission or reception would easily manifest themselves, for example, in the cases of MONSTER and MONARCH, MAGNET and MAGNOLIA. All in all, it is important to note that the compiler or compilers of these cipher books had adopted a principle known today as the "two-letter differential," a feature found only in codebooks of a much later date. In brief, the principle involves the use, in a given codebook, of code groups differing from one another by at least two letters. This principle is employed by knowledgeable code compilers to this very day, because it enables the recipient of a message not only to detect errors in transmission or reception, but also to correct them. This is made possible if the permutation tables used in constructing the codewords are printed in the codebooks, so that most errors can be corrected without calling for a repetition of the transmission. It is clear, therefore, that the compilers of these cipher books took into consideration the fact that errors are to be expected in Morse telegraphy, and by incorporating, but only to a limited extent, the principle of the two-letter differential, they tried to guard against the possibility that errors might go undetected. Had artificial five letter groups been used as code equivalents, instead of dictionary words, possibly the cipher books would also have contained the permutation tables. But it must be noted that permutation tables made their first appearance only about a quarter of a century after the Civil War had ended, and then only in the most advanced types of commercial codes.

There is, however, another feature about the words the compilers of these books chose as code equivalents. It is a feature that manifests real perspicacity on their part, and you probably already have divined it. A few moments ago I said that I would explain why, in the later and improved editions of these books, words that might well be words in plaintext messages were not excluded from the lists of code equivalents: it involves the fact that the basic nature of the cryptosystem in which these code equivalents were to be used was clearly recognized by those who compiled the books. Since the cryptosystem was based upon word transposition, what could be more confusing to a would-be cryptanalyst working with messages in such a system than to find himself unable to decide whether a word in the cipher text of a message he is trying to solve is actually in the original plaintext message and has its normal meaning, or is a codeword with a secret significance – or even a null, a nonsignificant word, a "blind" or a "check word," as those elements were called in those days? That, no doubt, is why there are, in these books, so many code equivalents that might well be "good" words in the plaintext message. And in this connection I have already noted an additional interesting feature: at the top of each page devoted to indicators for signaling the number of columns or rows in the specific matrix for a message are printed the so called "commencement words," or what we now call "indicators." Now there are nine such words, in sets of three, anyone of which could actually be a real word or name in the plaintext message. Such words when used as indicators could be very confusing to enemy cryptanalysts, especially after the transposition operation. Here, for example, are the "commencement words" on page 5 of cipher book No.9: Army, Anson, Action, Astor, Advance, Artillery, Anderson, Ambush, Agree; on page 7 of No. 10: Cairo, Curtin, Cavalry, Congress, Childs, Calhoun, Church, Cobb, etc. Moreover, in Nos. 1, 3, 4, 5, and 10 the "line indicators," that is, the words indicating the number of horizontal rows in the matrix, are also words that could easily be words in the plaintext messages. For example, in No.1, page 3, the line indicators are as follows:

Note two things in the foregoing list first, there are variants – there are two indicators for each case; and, second, the indicators are not in strict alphabetic sequence. This departure from strict alphabeticity is even more obvious in the pages devoted to vocabulary, a fact of much importance cryptanalytically. Note this feature, for example, in figure 62, that shows pages 14 and 15 of cipher book No. 12.

Address | 1 | Faith | Assume | 6 | Bend |

Adjust | 2 | Favor | Awake | 7 | Avail |

Answer | 3 | Confine | Encamp | 8 | Active |

Appear | 4 | Bed | Enroll | 9 | Absent |

In this respect, therefore, these books partake somewhat of the nature of two-part or "randomized" codes or, in British terminology, "hatted" codes. In the second lecture of this series, the physical difference between one-part and two-part codes was briefly explained, but an indication of the technical cryptanalytic difference between these two types of codes may be useful at this point. Two part codes are much more difficult to solve than one-part codes, in which both the plaintext elements and their code equivalents progress in parallel sequences. In the latter type, determination of the meaning of one code group quickly and rather easily leads to the determination of the meanings of other code groups above or below the one that has been solved. For example, in the following short but illustrative example, if the meaning of code group 1729 has been determined to be "then," the meaning of the code group 1728 could well be "the" and that of the code group 1730, "there."

But in a two-part code, determining the meaning of the code group 0972 to be "then" gives no clue whatsoever to the meaning of the groups 7621 or 1548. For ease in decoding messages in such a code, there must be a section in which the code groups are listed in numerical sequence and are accompanied by their meanings, which, of course, will be in a random sequence. The compilers of the USMTC code books must have had a very clear idea of what I have just explained, but they made a compromise of a practical nature between a strictly one part and a strictly two-part code, because they realized that a code of latter sort is twice as bulky as one of the former sort, besides being much more the laborious to compile and check the contents for accuracy. The arrangement they chose wasn't too bad, so far as cryptosecurity was concerned. As a matter of fact, and speaking from personal experience, in decoding a rather long message addressed to General Grant, I had a difficult time in locating many of the code words in the book, because of the departure from strict alphabeticity. I came across that message in a workbook in my collection, the workbook of one of the important members of the USMTC – none other than our friend Plum, from whose book The Military Telegraph during the Civil War comes much of the data I've presented in this lecture. On the flyleaf of Plum's workbook appears, presumably in his own handwriting, the legend "W.R. Plum Chf Opr with Gen. G.H. Thomas." Here's one of the messages (fig. 63) he enciphered in cipher book No.1, the book in which, he says, more important telegrams were sent than in any other: Note how many "arbitraries" appear in the plaintext message, that is, before transposition. After transposition, the melange of plain text, codewords, indicators and nulls makes the cryptogram mystifying.[8] And yet, was the system as inscrutable as its users apparently thought? It is to be remembered, of course, that messages were then transmitted by wire telegraphy, not by radio, so that enemy messages could be obtained only by "tapping" telegraph lines or capturing couriers or headquarters with their files intact. Opportunities for these methods of acquiring enemy traffic were not frequent, but they did occur from time to time, and in one case a Confederate signalman hid in a swamp for several weeks and tapped a federal telegraph line, obtaining a good many messages. What success, if any, did Confederate cryptanalysts have in their attempts to solve such USMTC cryptograms as they did intercept? We shall try to answer this question in due time.

1728 – the | 7621 – the |

1729 – then | 0972 – then |

1730 – there | 1548 – there |

As indicated earlier, there were no competing signal organizations in the Confederacy as there were on the Union side. There was nothing at the center of government in Richmond or in the combat zone comparable to the extensive and tightly controlled civilian military telegraph organization that Secretary Stanton ruled with such an iron hand from Washington. Almost as a concomitant, it would seem, there was in the Confederacy, save for two exceptional cases, one and only one officially established cryptosystem to serve the need for protecting tactical as well as strategic communications, and that was the so-called Vigenère Cipher, which apparently was the cipher authorized in an official manual prepared by Captain J.H. Alexander as the partial equivalent of Myer's Manual of Signals. You won't find the name Vigenère in any of the writings of contemporary signal officers of either the North or the South. The signalmen of those days called it the "Court Cipher," this term referring to the system in common use for diplomatic or "court" secret communications about this period in history. It is that cipher that employs the so-called Vigenère Square with a repeating key.[9] In figure 64 is the square that Plum calls the "Confederate States Cipher Key" and that is followed by his description of its manner of employment.

There are certain comments to be made on the two sample messages given by Plum. In the first place, in one of the messages certain words are left unenciphered; in the second place, in both sample messages, the ciphers retain and clearly show the lengths of the words that have been enciphered. Both of these faulty practices greatly weaken the security of ciphers because they leave good clues to their contents and can easily result in facilitating solution of the messages. We know today that cipher messages must leave nothing in the clear. Even the address and the signature, the date, time and place of origin, etc., should if possible be hidden; and the cipher text should be in completely regular groupings, first, so as not to disclose the lengths of plaintext words, and, second, to promote accuracy in transmission and reception.

So far as my studies have gone, I have not found a single example of a Confederate Vigenére cipher that shows neither of these two fatal weaknesses. The second of the two examples is the only case I have found in which there are no unenciphered words in the text of the message. And the only example I have been able to find in which word lengths are not shown (save for one word) is in the case of the following message:

Vicksburg, Dec. 26, 1862.

GEN J.E.JOHNSTON, JACKSON:

I prefer oaavvr, it has reference to xhvkjqchffabpzelreqpzwnyk to prevent anuzeyxswstpjw at that point, raeelpsghvelvtzfautlilaslt lhifnaigtsmmlfgccajd.

(Signed) J.C. PEMBERTON

Lt. Gen, Comdg.

Even in this case there are unenciphered words that afforded a clue enabling our man Plum to find the key and solve the message. It took some time, however, and the story is worth telling.

According to Plum, the foregoing cipher message was the very first one captured by USMTC operators, and it was obtained during the siege of Vicksburg, which surrendered on 4 July 1863. But note the date of the message: 26 December 1862. What was done with the captured message during the months from the end of December 1862 to July 1863? Apparently nothing. Here is what Plum reports:

What efforts General Grant caused to be made to unravel this message, we know not. It was not until October, 1864, that it and others came into the hands of the telegraph cipherers, at New Orleans, for translation. . . .

The New Orleans operators who worked out this key (Manchester Bluff) were aided by the Pemberton cipher and the original telegram, which was found among the general's papers, after the surrender of Vicksburg; also by the following cipher dispatch, and one other.

Plum gives the messages involved, their solution, and the keys, the latter being the three cited above. It would seem that if the captured Pemberton message had been brought to General Grant's attention and he did nothing about it, he was not much interested in intelligence. Second, the solution of the Pemberton message and the others apparently took some time, even though there was one message with its plain text (the Pemberton message) and two messages not only with interspersed plaintext words but also with spaces showing word lengths. But Plum does not indicate how long it took for solution. Note that he merely says that the messages came into the hands of the telegraph cipherers in October 1864; he does not tell when solution was reached.

In the various accounts of these Confederate ciphers, there is one and only one writer who makes a detailed comment on the two fatal practices to which I refer. A certain Dr. Charles E. Taylor, a Confederate veteran (in an article entitled "The Signal and Secret Service of the Confederate States," published in the Confederate Veteran, Vol. XL, August-September 1932), after giving an example of encipherment according to the "court cipher," says:

It hardly needs to be said that the division between the words of the original message as given above was not retained in the cipher. Either the letters were run together continuously or breaks, as if for words, were made at random. Until the folly of the method was revealed by experience, only a few special words in a message were put into cipher, while the rest was sent in plain language. Thus... I think it may be said that it was impossible for well prepared cipher to be correctly read by anyone who did not know the key-word. Sometimes, in fact, we could not decipher our own messages when they came over telegraph wires. As the operators had no meaning to guide them; letters easily became changed and portions, at least, of messages rendered unmeaningly [sic] thereby.

Frankly, I don't believe Dr. Taylor's comments are to be taken as characterizing the practices that were usually followed. No other ex-signalman who has written about the ciphers used by the Confederate Signal Corps makes such observations, and I think we must simply discount what Dr. Taylor says in this regard.

It would certainly be an unwarranted exaggeration to say that the two weaknesses in the Confederate cryptosystem cost the Confederacy the victory for which it fought so mightily, but I do feel warranted at this moment in saying that further research may well show that certain battles and campaigns were lost because of insecure cryptocommunications.

A few moments ago I said that, save for an exception or two, there was in the Confederacy one and only one cryptosystem to serve the need for secure tactical as well as strategic communications. One of these exceptions concerned the cipher used by General Beauregard after the battle of Shiloh (8 April 1862). This cipher was purely monoalphabetic in nature and was discarded as soon as the official cipher system was prescribed in Alexander's manual. It is interesting to note that this was done after the deciphered message came to the attention of Confederate authorities in Richmond via a Northern newspaper. It is also interesting to note that the Federal War Department had begun using the route cipher as the official system for USMTC messages very promptly after the outbreak of war, whereas not until 1862 did the Confederate States War Department prepare an official cryptosystem, and then it adopted the "court cipher."

The other exception involved a system used at least once before the official system was adopted, and it was so different from the latter that it should be mentioned. On 26 March 1862 the Confederate States president, Jefferson Davis, sent General Johnston by special messenger a dictionary with the following accompanying instruction:[10]

I send you a dictionary of which I have the duplicate, so that you may communicate with me by cipher, telegraphic or written, as follows: First give the page by its number; second, the column by the letter L, M, or R, as it may be, in the left-hand, middle, or right-hand columns; third, the number of the word in the column, counting from the top. Thus, the word junction would be designated 146, L, 20.

The foregoing, as you no doubt have already realized, is one of the types of cryptosystems used by both sides during the American Revolutionary period almost a century before, except that in this case the dictionary had three columns to the page instead of two. I haven't tried to find the dictionary, but it shouldn't take long to locate it, since the code equivalent of the word "junction" was given: 146, L, 20. Moreover, there is extant at least one fairly long message, with its decode. How many other messages in this system there may be in the National Archives I don't know.

Coming back now to the "court cipher," you will probably find it just as hard to believe, as I find it, that according to all accounts three and only three keys were used by the Confederates during the three and a half years of warfare from 1862 to mid-1865. It is true that Southern signalmen mention frequent changes in key, but only the following three are specifically cited:

1) COMPLETE VICTORY

2) MANCHESTER BLUFF

3) COME RETRIBUTION

It seems that all were used concurrently. There may have been a fourth key, IN GOD WE TRUST, but I have seen it only once, and that is in a book explaining the "court cipher." Note that each of the three keys listed above consists of exactly fIfteen letters, but why this length was chosen is not clear. Had the rule been to make the cipher messages contain only five-letter groups, the explanation would be easy: 15 is a multiple of 5, and this would be of practical value in checking the cryptographic work. But, as has been clearly stated, disguising word lengths was apparently not the practice even if it was prescribed, so that there was no advantage in choosing keys that contain a multiple of five letters. And, by the way, doesn't the key COME RETRIBUTION sound rather ominous to you even these days?

Sooner or later a Confederate signal officer was bound to come up with a device to simplify enciphering operations, and a gadget devised by a Captain William N. Barker seemed to meet the need. In Myer's Manual there is a picture of one form of the device, shown here in figure 65. I don't think it was necessary to explain how it worked, for it is almost self-evident. Several of these devices were captured during the war, one of them being among the items in the NSA museum (fig. 66). This device was captured at Mobile in 1865. All it did was to mechanize, in a rather inefficient manner, the use of the Vigenère Cipher.

How many of these devices were in existence or use is unknown, for their construction was an individual matter – apparently it was not an item of regular issue to members of the corps.

In practically every account of the codes and ciphers of the Civil War, you will find references to ciphers used by Confederate secret service agents engaged in espionage in the North as well as in Canada. In particular, much attention is given to a set of letters in cipher, which were intercepted by the New York City postmaster and which were involved in a plot to print Confederate currency and bonds. Much ado was made about the solution of these ciphers by cipher operators of the USMTC in Washington and the consequent breaking up of the plot. But I won't go into these ciphers for two reasons. First, the alphabets were all of the simple monoalphabetic type, a total of six altogether being used. Since they were composed of a different series of symbols for each alphabet, it was possible to compose a cipher word by jumping from one series to another without any external indication of the shift. However, good eyesight and a bit of patience were all that was required for solution in this case because of the inept manner in which the system was used: whole words, sometimes several successive words, were enciphered by the same alphabet. But the second reason for my not going into the story is that my friend and colleague of my NSA days, Edwin C. Fishel, has done some research among the records in our National Archives dealing with this case, and he has found something of great interest and that I feel bound to leave for him to tell at some future time, as that is his story, not mine.

So very fragmentary was the amount of cryptologic information known to the general public in these days that when there was found on John Wilkes Booth's body a cipher square that was almost identical with the cipher square that had been mounted on the cipher reel found in Confederate secretary of state Judah P. Benjamin's office in Richmond, the federal authorities in Washington attempted to prove that this necessarily meant the Confederate leaders were implicated in the plot to assassinate Lincoln and had been giving Booth instructions in cipher. Figure 67 is a picture of the cipher square found on Booth, and also in a trunk in his hotel room in Washington.

The following is quoted from Philip Van Doren Stern's book entitled Secret Missions of the Civil War (New York: Rand McNally and Co., 1951, 320):

Everyone in the War Department who was familiar with cryptography knew that the Vigenére was the customary Confederate cipher and that for a Confederate agent (which Booth is known to have been) to possess a copy of a variation of it meant no more than if a telegraph operator was captured with a copy of the Morse Code. Hundreds – and perhaps thousands – of people were using the Vigenére. But the Government was desperately seeking evidence against the Confederate leaders so they took advantage of the atmosphere of mystery which has always surrounded cryptography and used it to confuse the public and the press. This shabby trick gained nothing, for the leaders of the Confederacy eventually had to be let go for lack of evidence.

To the foregoing I will comment that I doubt very much whether "everyone in the War Department who was familiar with cryptography knew that the Vigenère was the customary Confederate cipher." Probably not one of them had even heard the name Vigenère or had even seen a copy of the table, except those captured in operations. I doubt whether anyone on either side even knew that the cipher used by the Confederacy had a name; or least of all, that a German army reservist named Kasiski, in a book published in 1863, showed how the Vigenère cipher could be solved by a straightforward mathematical method.

I have devoted a good deal more attention to the methods and means for cryptocommunications in the Civil War than they deserve, because professional cryptologists of 1961 can hardly be impressed either by their efficacy from the point of view of ease and rapidity in the cryptographic processing, or by the degree of the technical security they imparted to the messages they were intended to protect. Not much can be said for the security of the visual signaling systems used in the combat zone by the Federal Signal Corps for tactical purposes, because they were practically all based upon simple monoalphabetic ciphers or variations thereof, as for instance, when whole words were enciphered by the same alphabet. There is plenty of evidence that Confederate signalmen were more or less regularly reading and solving those signals. What can be said about the security of the route ciphers used by the USMTC for strategic or high command communications in the zone of the interior? It has already been indicated that, according to accounts by ex-USMTC men, such ciphers were beyond the cryptanalytic abilities of Confederate cryptanalysts, but can we really believe that this was true? Considering the simplicity of these route ciphers and the undoubted intellectual capacities of Confederate officers and soldiers, why should messages in these systems have resisted cryptanalytic attack? In many cases the general subject matter of a message and perhaps a number of specific items of information could be detected by quick inspection of the message. Certainly, if it were not for the so-called "arbitraries," the general sense of the message could be found by a few minutes' work, since the basic system must have been known through the capture of cipher books, a fact mentioned several times in the literature. Capture of but one book (they were all generally alike) would have told Confederate signalmen exactly how the system worked, and this would naturally give away the basic secret of the superseding book. So we must see that whatever degree of protection these route ciphers afforded, message security depended almost entirely upon the number of "arbitraries" actually used in practice. A review of such messages as are available shows wide divergences in the use of "arbitraries." In any event, the number actually present in these books must have fallen far short of the number needed to give the real protection that a well-constructed code can give. Thus it seems to me that the application of native intelligence, with some patience, should have been sufficient to solve USMTC messages – or so it would be quite logical to assume. That such an assumption is well warranted is readily demonstrable.

It was, curiously enough, at about this point in preparing this lecture that Mr. Edwin C. Fishel, whom I have mentioned before, gave me just the right material for such a demonstration. In June of 1960, Mr. Fishel had given Mr. Phillip Bridges, who is also a member of NSA and who knew nothing about the route ciphers of the USMTC, the following authentic message sent on 1 July 1863 by General George G. Meade, at Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, to General Couch at Washington. (See fig. 68)

It took Mr. Bridges only a few hours, five or six, to solve the cryptogram, and he handed the following plain text to Mr. Fishel:

Thomas been it-(Nulls)

For Parson. I shall try and get to you by tomorrow morning a reliable gentleman and some scouts who are acquainted with a country you wish to know of, Rebels this way have all concentrated in direction of Gettysburg and Chambersburg. I occupy Carlisle. Signed Optic. Great battle very soon. tree mush deal-(Nulls)

The foregoing solution is correct, save for one pardonable error: "Thomas" is not a "null" but an indicator for the dimensions of the matrix and the route. "Parson" and "Optic" are codenames, and I imagine that Mr. Bridges recognized them as such, but of course, he had no way of interpreting them, except perhaps by making a careful study of the events and commanders involved in the impending action, a study he wasn't called upon to undertake.

The foregoing message was enciphered by Cipher Book No. 12, in which the indicator THOMAS specifies a "Message of 10 lines and 5 columns." The route was quite simple and straightforward: "Down the 1st (column), up the 3rd; down the 2nd; up the 5th down the 4th."

It is obvious that in this example the absence of many "arbitraries" made solution a relatively easy matter. What Mr. Bridges would have been able to do with the cryptogram had there been many of them is problematical. Judging by his worksheets, it seemed to me that Mr. Bridges did not realize when he was solving the message that a transposition matrix was involved; and on questioning him on this point his answer was in the negative. He realized this only later.

A minor drama in the fortunes of Major General D.C. Buell, one of the high commanders of the Federal army, is quietly and tersely outlined in two cipher telegrams. The first one, sent on 29 September 1862 from Louisville, Kentucky, was in one of the USMTC cipher books and was externally addressed to Colonel Anson Stager, head of the USMTC, but the internal addressee was Major General H. W. Halleck, "General-in-Chief' [our present day "Chief of Staff"]. The message was externally signed by William H. Drake, Buell's cipher operator, but the name of the actual sender, Buell, was indicated internally. Here's the telegram.

COLONEL ANSON STAGER, Washington:

Austria await I in over to requiring orders olden rapture blissful for your instant command turned and instructions and rough looking further shall further the Camden me of ocean September poker twenty I the to I command obedience repair orders quickly pretty Indianapolis your him accordingly my fourth received 1862 wounded nine have twenty turn have to to to alvord hasty.

WILLIAM H. DRAKE

Rather than give you the plain text of this message, perhaps you would like to work it out for yourselves, for with the information you've already received the solution should not be difficult. The message contains one error, which was made in its original preparation: one word was omitted.

The second telegram, only one day later, was also from Major General Buell, to Major General Halleck, but it was in another cipher book – apparently the two books involved were used concurrently. Here it is:

GEORGE C. MAYNARD, Washington:

Regulars ordered of my to public out suspending received 1862 spoiled thirty I dispatch command of continue of best otherwise worst Arabia my command discharge duty of my last for Lincoln September period your from sense shall duties the until Seward ability to the I a removal evening Adam herald tribune.[11]

PHILIP BRUNER

As before, I will give you the opportunity to solve this message for yourselves. (At the end of the next lecture, I shall present the plain text of both messages.)

Figure 69 is a photograph of an important message that you may wish to solve yourself. It was sent by President Jefferson Davis to General Johnston, on a very significant date, 11 April 1865.[12] For ease in working on it, I give also a transcription below, since the photograph is very old and in a poor state. I believe that this message does not appear in any of the accounts I've read.

It is time now to tell you what I can about the success or lack of success that each side had with the cryptograms of the other side. I wish there were more information on this interesting subject than what I am about to present. Most of what sound information there is comes from a book by a man named J. Willard Brown, who served four full years in the Federal army's signal corps. The book is entitled The Signal Corps, U.S.A., in the War of the Rebellion, published in Boston in 1896 by the U.S. Veteran Signal Corps Association. In his book Brown deals with the cryptanalytic success of both sides. First, let's see what the Union signalmen could do with rebel ciphers. Here are some statements he makes (p. 214):

The first deciphering of a rebel signal code of which I find any record was that made by Capt. J.S. Hall and Capt. R.A. Taylor, reported Nov. 25, 1862. Four days later, Maj. Myer wrote to Capt. Cushing, Chief Signal Officer, Army of the Potomac, not to permit it to become public 'that we translate the signal messages of the rebel army'.

April 9, 1863, Capt. Fisher, near Falmouth, reported that one of his officers had read a rebel message which proved that the rebels were in possession of our code. The next day he was informed that the rebel code taken (from) a rebel signal officer was identical with one taken previously at Yorktown.

He received from Maj. Myer the following orders:

'Send over your lines, from time to time, messages which, if it is in the power of the enemy to decipher them, will lead them to believe that we cannot get any clew to their signals

Send also occasionally messages untrue, in reference to imaginary military movements, as for instance - 'The Sixth Corps is ordered to reinforce Keyes at Yorktown'.

Undoubtedly, what we have here are references to the general cipher system used by the Confederates in their electric-telegraph communications, for note the expression "Send over your lines." This could hardly refer to visual communications. Here we also have very early instances, in telegraphic communications, of what we call cover and deception, i.e., employing certain ruses to try to hide the fact that enemy signals could be read, and to try to deceive him by sending spurious messages for him to read, hoping the fraud will not be detected.

Brown's account of Union cryptanalytic successes continues (p. 215):

In October, 1863, Capt. Merril's party deciphered a code, and in November of the same year Capt. Thickstun and Capt. Marston deciphered another in Virginia. Lieut. Howgate and Lieut. Flook, in March, 1864, deciphered a code in the Western Army, and at the same time Lieut. Benner found one at Alexandria, Virginia.

Capt. Paul Babcock, Jr., then Chief Signal Officer, Department of the Cumberland, in a letter dated Chattanooga, Tennessee, April 26, 1864, transmitting a copy of the rebel signal code, says:

Capt Cole and Lieut. Howgate, acting Signal Officers, occupy a station of communication and observation on White Oak Ridge at Ringgold, Ga. . . . On the 22nd inst. the rebels changed their code to the one enclosed, and on the same day the abovementioned officers by untiring zeal and energy succeeded in translating the new code, and these officers have been ever since reading every message sent over the rebel lines. Many of these messages have furnished valuable information to the general commanding the department.

The following is also from Brown (p. 279):

About the first of June (1864), Sergt. Colvin was stationed at Fort Strong, on Morris Island, with the several codes heretofore used by the rebels, for the purpose of reading the enemy signals if possible. For nearly two weeks nothing could be made out of their signals, but by persevering he finally succeeded in learning their codes. Messages were read by him from Beach Inlet, Battery Bee, and Fort Johnson. Gen. J .G. Foster, who had assumed command of the Department of the South, May 26th, was so much pleased with Sergt. Colvin's work, that in a letter addressed to Gen. Halleck, he recommended "that he be rewarded by promotion to Lieutenant in the Signal Corps, or by a brevet or medal of honor." This recommendation was subsequently acted upon, but, through congressional and official wrangling over appointments in the Corps, he was was not commissioned until May 13, 1865, his commission dating from Feb 14, 1865.

(p. 281):

During the month, Sergt. Colvin added additional laurels to the fame he had earned as a successful interpreter of rebel signals. The enemy had adopted a new cipher for the transmission of important messages, and the labor of deciphering it devolved upon the sergeant. Continued watchfulness at last secured the desired result, and he was again able to translate the important dispatches of the enemy for the benefit of our commandants. The information thus gained was frequently of special value in our operations, and the peculiar ability exhibited by the sergeant led Gen. Foster once more to recommend his promotion.

(p. 286):

About the same time an expedition under Gen. Potter was organized to act in conjunction with the navy in the vicinity of Bull's Bay. Lieut. Fisher was with this command, and by maintaining communications between the land and naval forces facilitated greatly the conjoined action of the command. Meanwhile every means was employed to intercept rebel messages. Sergt. Colvin, assigned to this particular duty, read all the messages within sight, and when the evacuation of Charleston was determined upon by the enemy, the first notification of the fact I came in this way before the retreat had actually commenced. As a reward for conspicuous services rendered in this capacity, Capt. Merrill recommended that the sergeant be allowed a medal, his zeal, energy and labors fully warranting the honor.