CHAPTER 10

The Forgotten Ones: Pre-consumer Waste

Tony Dunnage

Group Director, Manufacturing Sustainability, Unilever

EXCESSIVE PACKAGING FOR PRODUCTS AND E-COMMERCE is something consumers notice and have been quick to criticize. There is a focus on the packaging waste they see and interact with, called post-consumer waste. But there’s more, as a significant amount of packaging and manufacturing waste is generated before a product reaches shelves—and in greater volumes and varieties than people realize.

What Is Pre-consumer Waste?

This waste stream, known as pre-consumer waste, is defined as material produced during the manufacturing process that does not make it into the final product. This includes but is not limited to the following:

![]() Packaging and wrappings used in the transport of raw materials from supplier to manufacturer

Packaging and wrappings used in the transport of raw materials from supplier to manufacturer

10.1 What happens to all the shipping and transport waste that gets products and their packaging from point A to point B (and C and D and…)?

Goritza/Shutterstock

![]() Trimmings and extras from primary, secondary, and tertiary packaging or product manufacture

Trimmings and extras from primary, secondary, and tertiary packaging or product manufacture

![]() Shipping and pallet waste from the transport of products and packaging from manufacturer to distribution center to retailers SEE 10.1

Shipping and pallet waste from the transport of products and packaging from manufacturer to distribution center to retailers SEE 10.1

Through this lens one can also consider products and packaging ordered in overstock, damaged, printed with out-of-date artwork, or returned to be pre-consumer waste.

Even though consumers may see it in a retail or advertising capacity, point-of-sale (POS) material (such as in-store signage, merchandising units, and billboards) and secondary packaging (what bulk products come in, like a crate for soda or a case of boxes of cereal) also fall into this category. Pre-consumer waste is rarely visible to the customer, is frequently overlooked during packaging design, and often ends up in the landfill or incinerator due to the costs of reintegrating it into the supply chain.

Business as Usual

Producers and manufacturers should be responsible for the end of life of packaging and what happens to it after consumers are finished. In the case of pre-consumer waste, there is even less room for attempting to push this responsibility downstream, as this material is still within the control of the factory, transport, and retail systems. Producers invest time and money into these systems, so it makes sense that they would retain accountability for their operations, including the management of their surplus and waste material.

With little economic incentive to account for these items and a lack of regulations compelling them to do otherwise, however, producers and manufacturers often remove themselves from responsibility, leaving someone else to deal with their pre-consumer waste. For example, POS and merchandising material has no use to the manufacturer after it serves its purpose of promoting a specific product for a particular season. It’s out of date and out of style, so the retailer doesn’t want it, either.

Without a reclamation system to keep this material with the manufacturer, the retailer, lacking the infrastructure to handle the material, throws it in the trash. The same goes for the secondary and tertiary packaging—the shipping and pallet materials that manufacturers and distributors use to bring products to market. Once the products are delivered, they no longer consider it their responsibility, leaving it with their retail customers to dispose of as they will.

Wasting such materials does come at a cost, but so do the processes to convert them. When it costs more up front to develop and implement these processes than it does to send the materials down the linear disposal route, off to the landfill or incinerator they go, valued as a negative. The result is often the loss of potentially useful material, supply-chain and resource maximization, and potential revenue streams, along with the political, social, and environmental externalities of waste.

Reverse logistics—the process of diverting usable material from linear disposal for the purpose of reusing it or capturing its value—necessitates systems that initially require resources to develop and execute. The needs and capabilities of the small packaging vendor differ from those of large CPG companies, which have their own factories and supply chains. But the path by which usable materials become waste is largely the same.

Pre-consumer material starts out with some worth in the eyes of the businesses that produce it because they are in possession of it. Manufacturers have long been keen on reusing and repurposing scrap in various ways. Supplying such materials to other companies or reintegrating them back into their own production lines ensures that resources continue to work for manufacturers, their customers, and the planet.

Current Challenges and Trends of Business-Driven Action

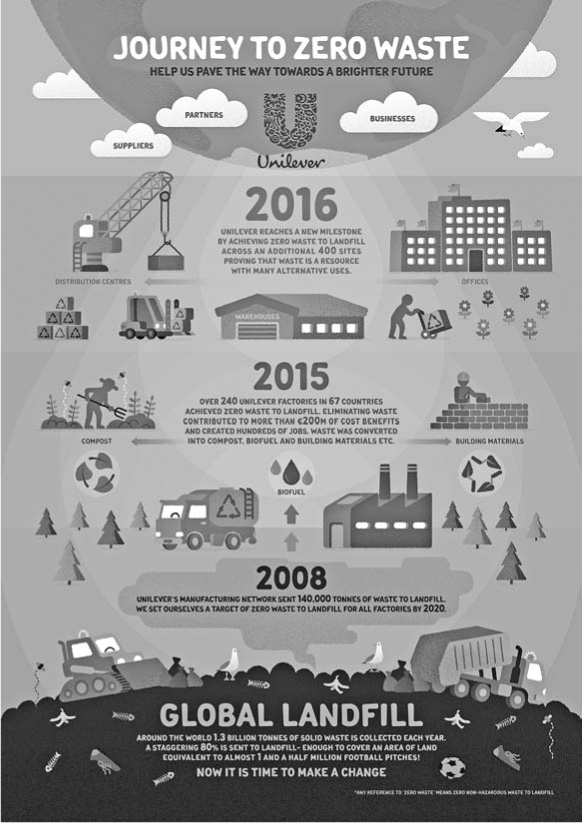

Full disclosure: In 2008 Unilever’s factories sent 140,000 metric tons of nonhazardous waste to landfill—that’s the equivalent of 2 million waste bins, or 17 Eiffel Towers. Given what Uni-lever has since managed to achieve, it almost seems unreal that we have ever done things any other way. But as is the case for any company today, the first steps on the sustainability journey entailed coming to terms with the fact that the business-as-usual way of doing things was no longer working and needed to change. SEE 10.2

In addition to an ambitious target of using 100 percent reusable, recyclable, or compostable plastic packaging by 2025,1 Unilever set the important, pivotal goal of achieving zero nonhazardous waste to landfill2 by 2020. Zero-waste-to-landfill (ZWTL) is a business concept in which solid waste produced at respective facilities is not landfilled but instead is reused, recycled, composted, or disposed of via some other outlet. Some companies regard ZWTL as a guiding ideal rather than a benchmark,3 and many seek certification4 for visibility.

At the core of these programs are continuous improvement and constant evaluation about material choices. There is not a one-size-fits-all approach to reducing waste in factories, but a strong commitment to eliminating waste at the source is the preferred place to start. Optimizing manufacturing to prevent trimmings from production prevents the need for reverse logistics, the next preferred step for resource management.

10.2 Unilever’s factories once sent 140,000 metric tons (or 2 million waste bins, or 17 Eiffel towers) of waste to landfill in one year. Their zero-waste journey started with the realization that “business as usual” had to change.

Unilever

The fast-moving and consumer packaged goods in the Unilever portfolio, which spans food and beverage, cleaning agents, and personal care products, have their own unique manufacturing streams. But thinking outside one’s sector of expertise to brainstorm on other industries may tap the creativity and imagination to come up with novel solutions for the business at hand.

Take textiles, for example. A durable good (all things considered, fast fashion notwithstanding) and far from the CPG realm, textiles produce huge waste streams both pre- and post-consumer. Optimized machines producing knitwear and sweaters in one piece, as well as cutting cloth from a pattern that keeps most of the source material intact, reduces the use of material and the need to recycle or dispose of it. The same concepts of optimization and one-piece production can be applied to fast-moving packaged goods.

Unilever successfully applied weight reduction as a production tactic, which has been implemented by many other CPG companies. Less weight for a package equals less scrap potentially sent to landfill. But unlike post-consumer, it’s still within your control and not up to municipal systems to recycle. One condiment company reduced the size of its bottles, openings, and spouts. This reduced the number of trimmings from molding the bottle, as well as the amount of wrapping material used to seal it.

The next way to eliminate waste sent to landfill is to integrate the inevitable production scrap. For the same reasons that separation has been the key to successful post-consumer waste diversion, much more action has occurred in pre-consumer waste reduction. Because the waste streams are comparatively uncontaminated and easier to separate at the point of generation, this is true in both the durable and nondurable goods sectors. SEE 10.3

10.3 Separation is one of the most important aspects of recycling, and the integral factor in maintaining resource utility for pre-consumer waste materials.

Unilever

Maintaining separation of materials is integral to this achievement and the expansion of reuse to other activities. One Japanese electronics and technology company developed a way to convert material from its solar panel production plant into usable powder for cement. As a result, the site’s factory waste “recycling rate” reached 93.5 percent (it is important to note that “recycling” into energy is the least favorable circular solution, though it’s better than landfilling).5 “Before” and “after” charts prepared and shared by each region have accelerated recycling improvements at underperforming locations.6

For Unilever a detailed mapping of every site’s unique mixed waste streams maintained material segregation through the provision of dedicated waste collection and storage points; this was the first step to developing action plans for reuse, recycling, or recovery, which were made available to all locations. This approach has meant reconsidering every single material that is consumed and encouraging transparency across operations.

Distance and the unique geographies and regulatory bodies of different locations are always challenges for reverse logistics, which require shipping, transport, and quality control of materials. Unilever has developed a number of replicable solutions and applicable contingencies for tackling waste:

![]() A solution developed in Kenya repurposes laminated wrapper waste into a versatile rigid construction material that can be formed into corrugated or flat panels for use in fencing and roofing.

A solution developed in Kenya repurposes laminated wrapper waste into a versatile rigid construction material that can be formed into corrugated or flat panels for use in fencing and roofing.

![]() A vermicomposting process in South Asia uses worms to break down manufacturing food waste into compost, which is used to fertilize organic vegetables for staff canteens and made available to employees and local communities for use in growing their own crops.

A vermicomposting process in South Asia uses worms to break down manufacturing food waste into compost, which is used to fertilize organic vegetables for staff canteens and made available to employees and local communities for use in growing their own crops.

![]() In a UK factory, raw and packaging materials are received in cardboard boxes. It has been found that the boxes can be reused by other industries directly without the need for recycling. This is not counted as waste because it helps reduce the consumption of natural resources.

In a UK factory, raw and packaging materials are received in cardboard boxes. It has been found that the boxes can be reused by other industries directly without the need for recycling. This is not counted as waste because it helps reduce the consumption of natural resources.

![]() In Australia reject stock tubs are turned into fertilizer. And a partnership with an innovative waste management company7 recycles surplus plastics from the food-and-beverage unit into underground pipe covers and garden edging.

In Australia reject stock tubs are turned into fertilizer. And a partnership with an innovative waste management company7 recycles surplus plastics from the food-and-beverage unit into underground pipe covers and garden edging.

![]() Tea bag paper from Russia is recycled into wallpaper.

Tea bag paper from Russia is recycled into wallpaper.

![]() In Africa and Latin America,8 hard-to-recycle materials are shredded and compressed at high temperatures to make school desks.

In Africa and Latin America,8 hard-to-recycle materials are shredded and compressed at high temperatures to make school desks.

These sorts of reverse logistics were facilitated with direct relationships between supplier and manufacturer, strengthened and developed through open dialogues. While collaboration is important, retailers and manufacturers will be more likely to accept and pilot innovative processes when they can see the value and sensibility of investing in them. By developing systems that worked for each facility, and then deploying to figure out how they could work for others, Unilever not only captures the value of material but generates gains through systems creation.

For example, Unilever updated pallet systems from the single-use wood pallet to reusable, durable plastic pallets that get repaired. Standardization of items such as pallets and intermediate bulk containers facilitates multiple uses and return systems that work across the industry—moving from single-use to multiple-use. This drives value for the facility and can be applied for others, creating a larger infrastructure for waste reduction and reuse.

10.4 At some manufacturing locations, repurposed laminated wrapper waste is converted into a versatile rigid construction material for products such as recycling bins.

Unilever

Here we ask: Why can’t this be done with other materials? Why not a collapsible plastic box? Why must secondary packaging and distribution and POS material be one-way, the energy and resources poured into them lost forever to linear disposal? By instead putting these items to good use, you can create value and save money for your suppliers, your customers, and other industries. SEE 10.4

One company achieves its zero-landfill goal by convincing suppliers to ship parts in reusable containers, which allows packaging for some 80 engine parts to be used multiple times instead of once.9

No matter what your manufacturing sector—durable or nondurable, packaged, luxury, or service-based goods—thinking about ways to get the most out of the materials you invest in will unlock possibilities at every turn.

At Unilever sites in many countries, waste material is recovered and used as alternative fuels to generate energy through a global partnership with a cement manufacturer and its waste management service provider. Combustible waste material, which was previously sent to landfill, is used as fuel in the cement manufacturing process. In Sri Lanka waste tea leaves are used as fuel in boilers, which also helps reduce carbon emissions. The material is pretreated and used as alternative fuel and raw material in cement kilns. Even the ash is used—and it is fully incorporated, thereby leaving no residues.

Despite the growing popularity of ZWTL in sustainability circles, many organizations still harbor the mind-set that it does nothing for the bottom line. You will find that it is quite the opposite.

The Impacts of Reducing Pre-consumer Waste

The early pioneers may not have taken the easiest or fastest path, but like the Wright brothers and their first airplane, it takes someone to prove what is possible. The Wright brothers didn’t go the farthest, and it wasn’t the most comfortable, but it was one of the first man-made machines driven by humans to fly through the air. Setting out to demonstrate that it is possible to reach goals that seem unachievable today is essential. SEE 10.5

Ultimately, Unilever achieved the ZWTL goal in 2014— six years ahead of target. This meant that more than 240 factories in 67 countries reused, recycled, or recovered all of their nonhazardous waste and sent nothing to landfill. Unilever’s sustainability leaders believed that the model and mind-set that drove the achievements in these factories would be repeatable beyond a manufacturing environment.

10.5 Like with the Wright Brothers and their first airplane, it takes someone to prove that pre-consumer waste diversion is not only possible but replicable.

Library of Congress

So, they set out to extend this to other parts of the business. By February 2016, nearly 400 additional Unilever sites, including offices, distribution centers, and warehouses in more than 70 countries, had achieved zero waste to landfill. Today Unilever sees no landfill waste in its factories, has proud and inspired employees, has achieved $234 million in annual savings and costs avoided (to reinvest back into the business), and has created 1,000 jobs in the wider economy.

They did all of this while reducing waste at the source and eliminating overconsumption of inbound materials. As a proud member of the CE100—a global platform bringing together leading companies, emerging innovators, and regions to accelerate the transition to a circular economy—Unilever employed circular-economy concepts10 to design renewably and reduce the amount of material used in production. This is the best solution environmentally and where the biggest savings are realized. By 2016 waste per metric ton of production was reduced by 37 percent compared with the 2008 baseline.

By bringing nonhazardous manufacturing waste to landfill to zero, Unilever unlocked two huge benefits. First, at a conservative but accountable estimate, 450 new jobs have been created for disabled and disadvantaged citizens in poorer parts of the world as a direct result of strategies for redirecting by-products and “waste” from manufacturing to new and useful purposes. SEE 10.6

Second, groundbreaking momentum for the business was driven with employees around the world. Shortly after the completion of these targets, Unilever held an event with competitors, peers, suppliers, and partners, inviting them to join this important journey.11 The presentation shared details of the methodology and introduced and highlighted best practices, hoping to amplify them across the industry. By designing once and deploying everywhere, Unilever hopes to help every business find its own model for zero waste.12

Sharing the model, rather than keeping it under wraps, is important for transparency—one of Unilever’s core values and an aspect of its culture. A transparent account of progress through engaging, insightful, and evidence-based reporting allows the garnering of the best feedback from consumers and stakeholders to keep improving.

10.6 ZWTL creates jobs and engages employees and stake-holders around the deployment of methods and models across industries.

Unilever

How Do I Do This in My Facility?

The first steps toward ZWTL can be difficult. Begin by focusing on what is most within control: the factories.

1. Start by analyzing facilities and processes you can easily control. Perform waste audits for your locations, testing each individual product, department, and process, to get a comprehensive idea about the factors influencing waste generation for your company. Taking stock of both positive and inefficient material flows will show where there’s room for improvement and highlight areas that can serve as models for other processes.

If you are a packaging buyer or small company that uses external vendors, ask to review their latest waste audits to get an idea of how sustainable your product really is. How much waste does your supplier send to landfill? Though your immediate operations may be relatively low impact, those of your vendors may not be and are thus worth a look.

2. Understand the changes and cost-cutting procedures that are possible. Based on the data gathered from a waste audit, potential changes in production processes, materials usage, and changes in the operating procedures governing waste activities will emerge. Perhaps a piece of machinery can use an update. Maybe you can commit or reorganize staff for a particular resource management team.

Mike Robinson, vice president of sustainability and global regulatory affairs for General Motors (GM), told Forbes: “A landfill-free program requires investment.…It’s important to be patient as those upfront costs decrease in time, and recycling revenues will help offset them.”13 When GM started its commitment to landfill-free manufacturing in 2005, it invested about $10 for every 1 ton of waste reduced. Over time it reduced program costs by 92 percent and total waste by 62 percent.14

Committing to a goal of diverting waste while considering costs may impact current supplier services, operations, and waste-handling practices. Audit and simulate different scenarios to figure out what is possible for your facility for the current year, in five years, and over the next decade. Cutting costs and improving your sustainability numbers may be a matter of working with different partners, investing in new materials, or eliminating a division.

Whether you outsource a consultant or dedicate the resources to develop your own sustainability division, understanding your company’s needs and priorities is one of the most important aspects of making a case to management, who ultimately must sign off on changes.

3. Get the support of company leadership. Not only do you need to get leadership on board for budgeting and resource purposes but you need to get them engaged in the communications that set the tone for the ZWTL journey. For Unilever, senior leadership support, with regular updates on the topic coming from the chief supply-chain officer, helped inspire and gain traction for ZWTL throughout the organization.

Changes in day-to-day processes and company structure in the name of reducing waste will not work without inspiration, motivation, and engagement from top-down leadership. Keeping everyone in the loop with reporting, information, and regular best-practice seminars and meetings is an investment of time in your personnel—the real resource.

4. Keep materials within your control when possible. If you have the capability, keeping materials within the closed systems of your factory locations is ideal. It eliminates the need to prepare or transport materials for sale, which comes at a cost, or to disclose sensitive information to vendors. Utilizing pre-consumer by-products to generate revenue or incur cost savings yields win-win situations.

Mapping waste streams and estimating costs helped Unilever’s factory teams understand where costs for disposal could be transformed into revenues through recycling and reuse, further supporting the case for action. Working with suppliers to reuse shipping materials is one of the simplest ways to do this. Materials that go back and forth over the same route are relatively easy to control and don’t require too much change from business as usual, save that of training staff and partners to reuse instead of grabbing new.

Having a strong network of suppliers committed to working with you on closed-loop systems can help you recycle your own factory waste into something you’d pay for anyway. For example, one of GM’s plants turns paint sludge waste into plastic material for shipping containers durable enough to hold engine components.15

5. Find markets for waste material. Commitments to go ZWTL can be hampered in parts of the world where the recycling infrastructure is lacking. As we know, this is most places, so finding markets for pre-consumer material can be a challenge. Working with your partners and suppliers to determine a fit within your network will help address these gaps. Viewing your waste as a marketable commodity is about finding a demand in the market for your supply.

Manufacturers in both your industry and others stand to save money by buying leftover packaging trimmings while allowing you to maximize the value of the material you purchased for production. Companies already exist that buy and sell commodity scraps like leather, molybdenum alloy, and pre-consumer paper; you could be the supplier. There’s a decent market for pre-consumer plastic waste, such as industrial packaging, as it is available at scale from fewer sources, making for a desirable product.

Creating a market for your materials by supporting the local recycling system is also important. Invest in new and emerging technologies to best position yourself. Micro-factories in Australia, for example, which show promise as a solution to current, centralized recycling facilities, are able to operate on a site as small as 50 square meters and can be located almost anywhere.16 Using these and other types of solutions in development may give them the boost they need—and you a nice discount on services as their initiatives continue to grow.

6. Aim for early wins. At the start of the journey, Uni lever knew it needed an early win and a repeatable reference to prove success once and then deploy widely. So, leaders decided to first focus on bringing ZWTL to operations in the United Kingdom. Data gathering, proposal tendering, and supplier selection began in 2010, and a nationwide partner to manage manufacturing waste was appointed. When the contract went into effect in July 2011, all 29 of Unilever’s UK locations, including 12 factories, achieved ZNHWTL, or zero-nonhazardous-waste-to-landfill, in a stroke.

Getting there had taken 11 months, but they had executed a template that could be rolled out across Europe. By the end of 2011, they’d successfully repeated the model to zero-waste manufacturing in Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg. Within a few more months, Italy too had achieved ZNHWTL.

7. Track progress and share resources. The key to recovering the highest value from pre-consumer waste is managing all by-products in one electronic tracking system. All Unilever plants monitor, measure, and centrally report their performance on a monthly basis, and the data are evaluated against companywide waste reduction goals. By engaging employees in the recycling effort, the data also help motivate factories to keep looking for creative solutions.

If one plant finds a valuable use for a by-product, it is quickly shared with other factories around the world. Reporting includes performance data for direct operations, as well as information about managing material issues across the extended value chain, which encompasses both the supply chain and how products reach consumers.

Practical activities such as “dumpster dives,” where Uni-lever factories emptied bins in front of management teams, demonstrated the need for recycling at each location. SEE 10.7 “Zero Hero” communities across geographies shared practical examples and experiences and collectively addressed issues. Zero Heroes highlighting successes and methods were fundamental in accelerating the program’s exponential performance.

Impacts can be far reaching. Identifying and prioritizing the most material impacts to your business and stakeholders to measure quantitative performance indicators will help monitor the development of specific risks over time.

10.7 Sorting and tracking activities such as dumpster dives take stock of company material streams and reduce the amount of waste sent to landfill, diverting what can be recycled or composted.

Dr. Bronner’s

Pre-consumer Waste: A Resource Management Issue

As one of Unilever’s employees said on the company’s ZWTL journey, “It’s like working on a mosaic, and every stone is worth adding to make it complete.” By setting a clear vision, creating a knowledge network, and empowering your people to act, you can inspire your employees and suppliers with zero-waste ambition.

Getting everyone in your organization and those you work with on the same page will not be easy—but it will be worth it. Full support and commitment from leadership streamlines processes and provides structure from the top down. Meticulous planning to deal with the unknown, total and utter commitment to the task, and a passion to succeed are the guiding elements of designing for zero waste.

Packaging design includes the processes associated with manufacturing, transporting, and distributing it. To make the most informed decisions about materials, suppliers, and reuse-and-recovery routes, producers must examine best practices from the manufacturing process for every link in the supply chain. Pre-consumer material becomes pre-consumer waste when business is unable to implement the systems that capture its value. Preventing such waste and increasing profits starts and swells with a plan.

Business-to-business waste management allows you to control every aspect of material flow, which saves time and money. Investing in reverse logistics—capturing value by moving pre- and post-consumer goods from their typical final destination of the landfill—takes full responsibility for your production.

Remember that sustainable supply chains are about people, not just processes. Human resources, inside your organization and out, are a renewable source of energy that when nurtured yield limitless returns. Stakeholders and consumers crave accountability, transparency, and learnings, and they care about who companies are at their core. By addressing problems with waste at the source, you carve out an essential place in the lives of consumers and the world at large.