2

The Evolution of Work

THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF NATURAL History in DC ranks as one of my favorite Smithsonian institutions of all time. If you get the chance, visit the Hall of Human Origins, put together by some of the most renowned scientists and researchers on the history of human fossils and artifacts in the world. The exhibit is organized as a chronological story of human history with displays of skulls, animal bones, cave paintings, and other archeological discoveries. The researchers who designed the exhibit cleverly explain how our bodies, brains, and behavior evolved over several million years and how this shaped how we live and look today. Probably the most impactful part of the exhibit for me was walking by the artistically rendered life-size busts of early humans. I remember reading about many of these early hominids in college, like Australopithecus afarensis (Lucy), Homo erectus (Walking Man), and Homo neanderthalensis (Neanderthals), and this exhibit really made them feel more real.1

Walking through time in this way got me thinking more deeply about our past and the major milestones that have transformed how we live and work today. According to the exhibit’s timeline, 6 million years ago we began walking upright, 2.6 million years ago we started eating meat, 1.8 million years ago we started traveling (using our long legs to move from Africa all across the Earth), 800,000 years ago we began cooking, and only 10,500 years ago we started farming and domesticating animals. But the most striking evolution, from a food and exercise point of view, happened sometime between 1 million and 800,000 years ago to our evolutionary grandparents, H. erectus.

WALKING MAN

Early humans ate mostly plants, roots, and bark—a similar diet to chimpanzees, gorillas, and other primates today. But starting with H. erectus, anthropological evidence shows a major change in brain size, body size, diet composition, and foraging behavior that had a profound influence and shaped our nutritional and energy demands forever more.2 During this time, our brain size started outpacing our body size (proportionately) so much so that if you look at human skulls before and after this time, we almost appear to be a totally different species. Most scientists believe our brain enlargement (and the shortening of our intestines) was the result of an increase in the quality of nutrition in our diet (meat, bone marrow, and other nutritionally dense foods), and some believe it coincided with the invention of cooking, when we figured out how to extract more nutrients out of what we ate.3

This nutrition density in our diet caused our brains to grow, so much so that the human brain beginning then, and still today, consumes roughly 20 percent of the calories we take in each day. To feed our hungry heads, we had to search for more and more nutrients, which incentivized us to look for even more kinds of nutrient-rich foods.4 With all this motivation to expand our palate, I cannot help but think about my steely resolve to push my kids to try new foods all the time, just like my mom did. “Try it, you’ll like it!” turns out to be a survival measure, passed on by mothers for literally a million years.

Dr. Briana Pobiner, a research scientist with the Smithsonian Institution and one of the people responsible for putting together the Human Origins exhibit, has studied the human evolution diet, in particular the Paleolithic diet from between 2.5 million and 1 million years ago, in eastern and southern parts of Africa. So of course, when I got the opportunity to speak with her, my first question was: “So, what do you think of the Paleo Diet?” She immediately laughed. (I guess she gets this question all the time.) Then she set the record straight:

On the one hand, I really love the way this diet has elevated the field of paleoanthropology. Few people knew it existed before now! On the other hand, I find there are some real flaws with the Paleo Diet nutritionally. For example, the diet does not encourage eating grains or dairy, claiming that we have not evolved enough to digest them. This is not true, as we have clear genetic adaptations to both that date back at least several thousand years. My second issue with the diet is that it seems to assume that what our ancestors ate was always good for them. This was often not the case. Our early ancestors were often starving, eating poorly, and most died by the time they were 35 or 40.5

So fine, I guess we did not always have the best food choices way back when. But if we could go back in time, in an ideal world, what should we have put on the menu to best meet our energy needs?

Interestingly, modern-day hunter-gatherer societies (a proxy for understanding hunter-gatherers of long ago) tend to eat higher levels of protein than people in modern industrial societies, but it is unfair to say that there is a strict norm for how people should eat, either now or in the distant past. Some subsistence groups from arctic populations today have a diet almost exclusively consisting of animal material, and some small-scale farming societies subsist on a mix of plant and animal foods. The diversity of our diets is as diverse as we are as people. To quote Marlene Zuk, an evolutionary biologist and behavioral ecologist and author of Paleofantasy, “There was no single Paleo Lifestyle, any more than there is a single Modern Lifestyle. Early humans trapped or fished, relied on large game or small, or collected a large proportion of their food, depending on where in the world they lived and the time period in which they were living.”6

The big difference, it seems, from the way we ate 2 million years ago versus today is that then, we spent an enormous amount of energy hunting and scavenging for fresh food, whereas today, our food is processed and comes to us by way of a grocery store. William Leonard, head of the Department of Anthropology at Northwestern University, and his colleagues estimate that based on modern hunter-gathering practices, our evolutionary grandparents walked or ran an average of 13.1 kilometers (8 miles) a day, looking for food. The other key aspect of physical activity in subsistence societies is the fact that much of the daily work was done at a slow to moderate pace versus high-intensity workouts.7 These people slowly burned energy looking for food all day. So for most of human history, the work of hunting and scavenging was pretty much a full-time job.

Leonard also looked at the body mass index (BMI) of modern subsistence farmers, herders, and hunters. He found that among males, the mean BMIs for the subsistence groups ranged from 20.4 to 22.5, with the average for each group significantly less than that of industrialized nations. The patterns were similar for women.8 Subsistence farmers tend to exercise more and throughout the day and eat just enough to support their lifestyle.

According to Leonard, early humans had “high physical energy expenditure and frequent periods of marginal or negative energy balance,” meaning there was often more energy leaving than going into their bodies. They were thin because they ate a steady diet of nutrition-rich foods and burned off energy as they consumed it. At a certain point in history, however, the way we collected, prepared, and consumed food changed pretty dramatically. And the triggers for this are fascinating.

FARMING AND ANIMAL DOMESTICATION

Farming has been part of human existence for roughly 10,500 years. Its inception was an incredible moment in human history, when we no longer needed to run around all day looking for food to survive and could focus instead on transforming our surroundings by planting, watering, raising crops, and tending herds. A new way of life emerged, as we focused on growing agriculture and building cities. Paleoanthropologists believe that this transformative change happened for two big reasons. According to Richard Potts and Christopher Sloan, who wrote the companion book to the Smithsonian exhibit, What Does It Mean to Be Human?, “First was the suite of physical, mental, social and technological traits that had accumulated over the course of human evolution. Second was the rapidly thawing environment at the end of the last ice age, followed by a relatively stable climate.”9

With a big break in the weather as the planet became warmer and wetter, we figured out how to domesticate cows in Africa and the Middle East (10,000 years ago), grow squash in Central America (10,000 years ago), cultivate corn in North America (9,000 years ago), and grow rice in China (9,000 years ago).10 Almost at the same time worldwide, we leveraged all of the skills we had collected throughout our hunter-gather years—to make tools, hunt animals, cook, store food, and create huts, hearths, and clothing—and used them to become very good farmers. But we also became more planted in one place. No need to wander around looking for food if you can grow it easily in your backyard! So with domesticated plants and animals, all of our ancient cities were born, along with increased crop yields, drought tolerance, easier harvests, and better nutrition.

As incredible as it was from a food production of view, the movement to farming was not that easy. Living in close quarters and in more dense urban settings for the first time put people at risks for diseases and maladies they might not have had to deal with on the open range. Plus, it was very physically taxing. For example, a study was done in 2011 that gives us a glimpse of the level of exertion required by early small farmers in our evolutionary history. The study looked at the physical activity of Amish and non-Amish adults in Ohio Appalachia, measuring the number of steps they took. The researchers specifically looked at Amish farmers because their work is more labor-intensive than industrial agriculture practices today (they don’t rely on modern equipment) and is more proximate to the way farmers might have worked in the distant past. Male Amish farmers took 15,278 steps (roughly 7 ½ miles) per day on average, whereas non-Amish men from the same area took 7,605 steps a day. (Interestingly, the study concluded that the farmers’ higher levels of physical activity may be a contribution to lower cancer incidence rates documented among this Amish group.11)

Farming was then and still is for some communities laborious dusk-till-dawn work, but with the increased number of domesticated animals, better tools, and eventually the invention of machines and industrial processes, life got a little easier. In fact, it was the Industrial Revolution that allowed some of us, for the first time in our evolutionary history, to stop thinking about “what’s for dinner” all the time and instead explore the arts, sciences, and other pursuits not related to food gathering.

FACTORIES AND GIN CARTS

The Industrial Revolution came into full swing in the late 1700s and early 1800s, when almost every facet of daily life changed. Most economic historians agree that the onset of the Industrial Revolution was the most important event in the history of humanity since the domestication of animals, plants, and fire. The average income and the population began to exhibit unprecedented and sustained growth. How we produced food, clothing, and buildings changed, whole transportation systems were created, a professional middle class emerged, and the language of work changed. Terms like “productiveness” (circa 1727) and “productivity” (circa 1809)—words still in use today in business—were first used to describe a new way of thinking about how we create value. Work was no longer about what humans could do but what humans could do with the help of machines.

Factory buildings were perfect physical manifestations of the business theories and concepts they were supporting—in other words, of “productivity.” Most of these buildings were efficiently organized, sizable, and open, designed with the latest technology at the time to beautifully accommodate machinery and to allow factory managers to observe the work being done by their vast labor force. However, the buildings were typically not designed so well for the health of workers who regularly inhaled coal fumes, put in 12+ hours a day performing monotonous tasks, and were forced to endanger themselves regularly to keep production levels high.

In the early 1700s in England, even before the Industrial Revolution was in full swing, gin carts (vending carts on wheels carrying gin) became popular in places like London and Manchester, rolling up and down the streets and even down factory floors to keep people working in these dismal conditions. And despite the miserable nature of the work for many factory laborers, and the fact that they were in large part alcoholics, their work did involve regular movement and exercising their bodies as part of their job. The good news is that through the 1800s and 1900s, several major labor movements put limits on the number of hours that could be worked, environmental laws improved air quality, business and building codes began protecting worker safety, machines were designed with ergonomics in mind, and people stopped drinking large amounts of gin (which had not exactly been good for laborers’ safety working around large, sometimes dangerous machinery).

Also, in reaction to seeing the squalor and poor conditions of factory life, some business leaders began integrating the health of their workers into their business model as a way of keeping them fit, productive, and loyal to the company. For example, in 1888, the village of Port Sunlight, in Merseyside, England, was built by the Lever Brothers to accommodate workers in their soap factory. Port Sunlight included public buildings such as the Lady Lever Art Gallery, a cottage hospital, schools, a concert hall, an open air swimming pool, a church, and a temperance hotel (where no alcohol was served). Lever Brothers introduced welfare schemes and provided for the education and entertainment of their workforce, encouraging recreation and organizations that promoted art, literature, science, or music.

In the United States, around 1905, Milton Hershey built a chocolate factory with worker health and well-being in mind in what is now Hershey, Pennsylvania. Hershey created a completely new community around his factory including comfortable homes, a public transportation system, a quality public school system, and extensive recreational and cultural opportunities. Unlike other industrialists of his time, Hershey wanted to avoid building a faceless company town with row houses. He wanted a “real home town” with tree-lined streets, single- and two-family brick houses, and manicured lawns. He was concerned about providing adequate recreation and diversions for his employees and their families, so he built an amusement park that opened in 1907 and expanded rapidly over the next several years. This amusement park continues to be a strong part of the community, even today.

WORK IN THE 20TH CENTURY

The past 100 years have included major changes that have shifted how we work once again, and in fairly profound ways. We’ve gone from riding horseback to traveling on airplanes, from using pencils to iPads, from working in factories to hanging out in coworking facilities. In most industrialized countries, there has also been a shift from manufacturing-based businesses to service businesses. All of these changes are particularly fascinating to witness by peaking inside the buildings where people worked. In many ways, the buildings were a manifestation of the nature of work happening inside them. They still are. Let’s look at some of the changes in office space over the last 100 years.

The “Factory” Office

The “Factory” Office

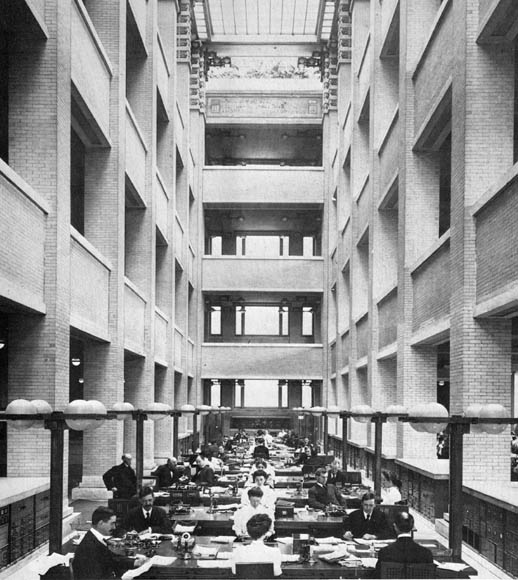

In the early part of the 20th century, the first large office buildings looked and behaved a lot like factories. Only at this point, workers were not pushing machines; instead, they started pushing paper. The Larkin Building, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright and built in 1906 for the Larkin Soap Company in Buffalo, New York, was a great illustration of innovation in many ways. The five-story dark red brick fortress of a building had air conditioning, stained glass windows, built-in desk furniture, and suspended toilet bowls (designed by Wright so that the floors were easier to clean). As innovative as this building was, it looked and felt like a factory, especially in the large atrium space full of rows of workers performing administrative work. (See Figure 2-1.)

Figure 2-1. The interior of the Larkin Building, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright.

The Office Tower

The Office Tower

As building technology improved and big business continued to blossom in cities, a number of very tall and very wide office buildings appeared. Many of these buildings appeared in New York City at the beginning of the 20th century—like the Metropolitan Life Tower (1909), Woolworth Building (1913), and Chrysler Building (1930)—but they popped up in every major city in the coming decades. To give you a sense of scale, the Empire State Building in New York, completed in 1931, includes 2.25 million square feet of occupied space, which, as of 2007, housed roughly 1,000 companies and 21,000 people. What this meant at a practical level for those working in these spaces is that they were surrounded by a busy hive of people day in and day out.

Jack Lemmon, in the movie The Apartment (1960), was supposed to have worked for a “large insurance company,” likely modeled after the interior space of one of these large buildings. (See Figure 2-2.) Just imagine even more paper pushers, shoved together, sitting at open desks with enclosed offices surrounding the perimeter of the space cutting off all natural light. Then add in lots of noise created by people shouting on phones, the clacking of typewriters, and wafts of cigarette smoke everywhere, and you get a sense of what work was like in these buildings.

Cube Farms

Cube Farms

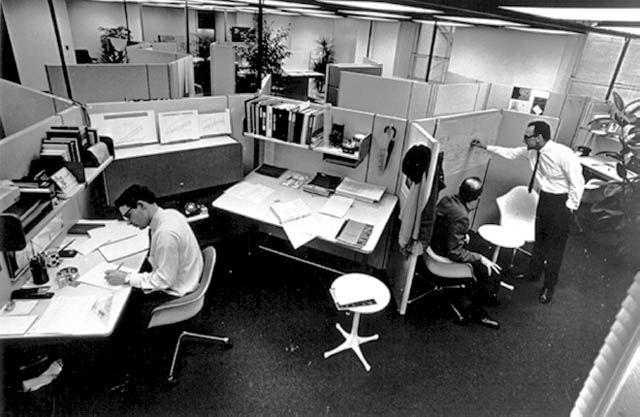

Then, in the 1960s, the cubicle was born. This new kind of open office was introduced by a few designers, but most notably Robert Propst from Herman Miller, a large furniture manufacturer. The initial design idea for the cubicle was to provide more productivity, privacy, and health in the open environment, and to allow workers to easily configure or reconfigure their work area with modular elements such as work surfaces, overhead bins, drawers, and shelving. The first Propst cubicle designs, called Action Office in 1968, had varying heights and surfaces. (See Figure 2-3.) Over time, cubicles became more regular and efficient in shape, taller, and the butt of Dilbert cartoon jokes. Probst later claimed that “The cubiclizing of people in modern corporations is monolithic insanity.”12

Figure 2-2. Scene from the movie The Apartment.

Figure 2-3. Herman Miller’s Action Office furniture system.

The Mobile Office

The Mobile Office

In the early 1990s, largely because of the incredible influence of mobile technology (laptops, tablets, cell phones, etc.), it became possible to work away from the office, untethered from a cubicle, and instead work virtually with coworkers. Full-time homeworking increased in popularity as did telecommuting (working part time from home) and working in satellite offices. Employees no longer had to be in the same place or even work at the same time as their teammates. As an example, in 1992, the federal government began piloting a series of interagency satellite offices for workers in and around Washington, DC, to enable telework and reduce congestion and workers’ commutes into the city.

From a health and wellness perspective, the transformation of our work style over the last several decades, from factory to cubicle to home (either full time or on occasion), has impacted our health for good and for bad. On the positive side, office buildings and public spaces everywhere are now relatively smoke-free, and ergonomics have emerged as a multidisciplinary profession and resource.13 We also have more choice than ever in how we work individually and in groups, to suit different personalities, skills, and preferences. Unfortunately, these changes in our work and our work environment are also impacting our health in negative ways.

A study of occupations done by Dr. Tim Church from the Pennington Biomedical Research Center and others compared levels of physical activity for the entire American workforce over the past five decades. They found that workers in 2010 burned fewer calories, on average, than people in previous generations, purely based on the increased prevalence of more sedentary jobs. According to their findings, “Over the last 50 years in the U.S., we estimate that daily occupation-related energy expenditure has decreased by more than 100 calories, and this reduction in energy expenditure accounts for a significant portion of the increase in mean U.S. body weights for women and men.” Back in the early 1960s, almost half of private industry occupations in the United States required at least moderate-intensity physical activity. Today, 80 percent of Americans have jobs that are classified as sedentary or require very light physical activity.14

WORKING TODAY

Fast forward to today. A significant part of the research I do as a workplace specialist involves observing people in workplaces—otherwise known as workplace anthropology. It is a technique that assesses how people space is used by tracking people in space with technology, following people around, and lots of observing. It is amazing what you can learn about work patterns and behavior, even when people are not around to tell you what is happening. Using data within the past few years from observations of roughly 40,000 work points (i.e., offices, workstations, bench seats, conference rooms, break areas, cafeterias, etc.), survey data from 23,000 people globally, and a few other sources, here is a quick summary of work life today for knowledge workers.15

The Hours We Work

The Hours We Work

Workers in the United States and Canada clock in 1,705 hours a year, which is slightly more than workers in the UK (1,650), France (1,476), and Germany (1,406) but significantly less than in Taiwan (2,144) or Singapore (2,287).16 At least that is what we put on our timesheets. Many of us also put in extra unbooked hours. A survey put out by Good Technology, a mobility security company, found that some 80 percent of the 1,000 Americans polled said they spend 7 extra hours a week, or 30 extra hours a month, checking emails and answering phone calls after hours.17 So for years, laborers in countries everywhere fought hard to limit our workweek to 40 hours, and almost instantaneously with the invention of mobile technology, we threw this right out the window.

Where Work Happens

Where Work Happens

Most knowledge workers are sitting in their office only 52 percent of the time. The rest of the time they are in a conference room, the cafeteria, working at home, on a plane, on a train, in a hotel, or on a grocery line. If someone asked you “Are you a mobile worker?” you can probably say yes. You are mobile because you work in lots of places throughout your day and week. That is also likely true as well if you work in a school, a hospital, an airport, or any profession that requires working in more than one primary location. That said, just because you are mobile does not mean you are actually moving. Our work has actually become much more sedentary since we have been tethered to our beloved electronic devices.

What We Do While Working

What We Do While Working

When knowledge workers are in the office, they spend 37 percent of their day, on average, collaborating. Most of that collaboration time is spent collaborating with others remotely (web-, tele-, or videoconference meetings), and a surprisingly small amount of collaboration time is spent in face-to-face meetings. Of course, a number of organizations encourage people to get together and talk in person more often, but you would be surprised how little this actually happens today. More likely than not, we are collaborating through some sort of device. Also, most office workers sit the majority of the time they are working. Studies vary, but on average, office workers have been found to sit 68 to 82 percent of an eight-hour day. Even jobs where you would think people would not sit so much—like being a teacher or working in a lab, for example—can require significant paperwork, research, analysis, etc., which requires sitting for many hours at a time.

Our Eating Habits at Work

Our Eating Habits at Work

Only a third of American workers say they take a lunch break, and 65 percent of workers eat at their desks or do not take a break at all, according to a Web survey conducted by Right Management, a human resources consulting firm.18 Those eating while working probably ate more and felt less full after a meal than their nondistracted coworkers who were exclusively focused on eating.19 Eating while you work is not just bad for digestion. You actually eat more and get hungrier later.

And what about all of that snacking from vending machines? In 2012, the vending business in the United States reached $19 billion, with 22.5 percent of sales in manufacturing facilities, 21.1 percent in offices, and 6.6 percent in hospitals.20 Vending machines are so prevalent and so impactful to our diet that the Food and Drug Administration announced that in an effort to combat obesity, roughly 5 million vending machines nationwide were required to display calorie information starting in 2014 as part of the Affordable Care Act.21

What the Workplace Looks Like

What the Workplace Looks Like

Offices built for knowledge workers today (versus those built more than 10 years ago) tend to dedicate fewer square feet to individual offices, with more space for collaborative areas and amenities (like nap rooms, telephone booths, quiet rooms, cafeterias, training rooms, and break areas). These additional spaces are designed to be places for working, not just talking about sports or what your kids are doing, though this informal discussion is helpful for building business relationships. In general, having more choice in where you work is a good thing for productivity, for satisfaction, and for supporting the varied nature of knowledge work and the increase in mobility (which we will dig into deeper in Chapter 3). Unfortunately, many of the buildings where work happens today are still designed like factories from the Industrial Revolution. They might be tightly packed, dark, or have poor indoor air quality. They might provide only one way to work (sitting glued to one seat) without any ability to adjust furniture, lighting, or equipment to respond to the human need to walk, sit, stand, or even rest during the workday.

Who Is Working Today

Who Is Working Today

For the first time in history, up to five generations are actually living at the same time, which is a medical miracle in itself, but we are also working together in the same organization. And though most people in the veteran generation (born before 1946) have retired by this point, we can’t assume people from the Baby Boomer generation (born between 1946 and 1964) will retire anytime soon. In fact, if you ask Boomers when they are going to retire, chances are they will be offended by the question. The result is that more people are expanding the number of years they choose to work. Long term, we can assume that a larger percentage of the workforce will suffer more and longer from ailments caused by unhealthy work practices if we don’t change our work style now.

![]()

In summary, office work patterns today are extremely boring and not exactly healthy by anyone’s standard. Believe me, I’ve been watching you! When my team performs workplace observations, sometimes we have to overload on coffee just to make it through our research. Every once in a while I would just love to see someone break out in song with a set of resistance bands or go running through the halls, just to make this part of my job a little more exciting. With the exception of going to the bathroom or grabbing coffee every now and then, most office workers are glued to their desk, mindlessly eating and talking or typing on devices. I’m sure they are aware there is a gym, an outdoor area, or a nice break room, but they don’t use these very much because, well, that is often not perceived as productive time. That said, what is productivity anyway? It seems like that term is thrown around quite a bit, but what is our connection to it and is it even the right term to explain the output of our work today?

Before we dive into the details of how to increase productivity, it’s worth first understanding the term a little more. When I’m designing a new workplace or coming up with a workplace strategy for an organization, leaders often state that one of their key goals is “to increase the productivity of their employees.” When I ask what that means, I have found that the answer varies widely based on industry, on job function, even on the individual. It’s important to put a stake in the ground and define what it means to be productive today, so that solutions for improving productivity (and health) are put into context. The language and definitions we use are important, especially when making the business case for changing organizational, team, and individual behaviors.