yeqyx ipeoa ipeco caozr ivmzi oatab

- - - - - - - - - - - - - -

(Pineapple must be packed very carefully. Mark outside of packages plainly, with gross and net weights. Customers will pay for cost of transshipment. Telegraph us at time shipment is made.)

orutl yeqyx oczom

- - - - - - - - - - - - - -

(In accordance with your telegram, pineapple will be shipped immediately.) – English texts and commercial code equivalents from Acme Commodity and Phrase Code, New York, 1923

Very quickly after the introduction of the American Morse code for telegraphic messages, it was recognized that this new mode of communicating seriously threatened privacy. Inserted between the originator and intended recipient of the information were persons who would translate it into the Morse symbols and key the message and other individuals to receive the message and render it readable for the recipient. The most sensitive data would, therefore, be accessible to these middlemen. Thus, in 1845 an associate of Samuel Morse published a code for Morse communications, "The Secret Corresponding Vocabulary; Adapted for Use to Morse's Electro-Magnetic Telegraph," to provide the message originator with a means of securing correspondence.

As telegraph usage grew in the late 1840s and 1850s, other codes for Morse communications appeared, but it was the laying of the first transatlantic cable in 1866 that sparked an explosion of codes for Morse communications. The driver for this creativity was not secrecy, but economy, for the telegraph companies charged by the word, as well as according to the distance between the sender and the receiver. Consequently, the economies offered by the shorthand codes, which became known as "commercial codes," were extremely attractive. Scores of industries developed lexicons that could, with a simple group of letters, convey multiple phrases or sentences.[22] During WWII, the information transmitted by foreign companies by this means was of interest to U.S. officials, since it could provide trade and travel data and some insight into the economic conditions of the companies' host nations.

An SIS unit of four people, all Caucasians, was actively exploiting foreign commercial coded messages as early as February 1943. By May there were six, and in September 1943 eight people comprised B-2a-8, the Commercial Unit in the Code Recovery Section of the Cryptanalytic Branch. The unit was headed by a succession of junior Army officers in the fall of 1943, but gradually the personnel were transferred to other higher priority tasks, and by December 1943 the mission was completely abandoned.[23] It was a situation tailor-made for the moment. No Caucasians were working the problem, obviating the need to address the issue of an integrated work unit. Clearly the work was meaningful, but if no results were produced, it would only be a continuation of the status quo for the customers. On the other hand, if the unit proved productive, the results could be useful. Mrs. Roosevelt's requirements could be met.

In January 1944, Bill Coffee started his new assignment as a cryptographic clerk. Undoubtedly he underwent some cryptanalytic training, but a record of courses that he might have taken at the time is no longer available. Initially he worked alone; then in February 1944 Annie Briggs, who had worked with him in the messenger unit, joined him as his assistant.[24] The unit grew in size and, though clearly an operational unit with core mission responsibilities, for several months it was retained as a staff element reporting to the chief of the Cryptanalytic Branch, consistent with Corderman's direction to Cooke. A memorandum announcing one of the many Signal Security Agency reorganizations alluded to this inconsistency:

Effective 21 August [1944], the Intelligence Division [formerly the Cryptanalytic Branch or B Branch] was organized to consist of an Office of the Division Chief and five operating branches. . . . The Commercial Traffic Section has, for reasons of policy, been retained under the control of the Division Chief instead of being absorbed into the General Cryptanalytic Branch [one of the five subordinate branches of the Intelligence Division], which might normally appear to be its proper location.[25]

Eventually, however, logic prevailed. By mid-November 1944, the unit became part of the General Cryptanalytic Branch, which was headed by Lieutenant Colonel Frank B. Rowlett, one of the four original cryptanalysts hired by William Friedman. Its designator became B-3-b. The organizational chart reflects Lieutenant Benson K. Buffham as the chief and William D. Coffee, assistant civilian in charge.[26]

B-3-b, under Lieutenant Buffham and Bill Coffee, exploited nongovernmental commercial code messages originating from Australia, Great Britain, Germany, Sweden, Spain, Portugal, Bulgaria, Turkey, Afghanistan, Russia, China, Indochina, Thailand, Japan, Egypt, South Africa, Ecuador, Uruguay, Paraguay, Brazil, Peru, and Argentina.[27]

Conventional intercept sources and the Office of Censorship, which under the War Powers Act received copies of all cable traffic from the U.S. carriers, supplied the raw material (messages) for the unit. Communications using both private codes and codes available on the open market were decoded. Messages that were found to be written in an unknown commercial code or in an enciphered commercial code, i.e., individual letters of the code phrase were substituted or transposed, were analyzed to identify the underlying codebook and ultimately to recover the plain text. Additionally, the unit sorted and routed nongovernmental Spanish, French, Italian, Portuguese, German, and English plaintext messages, a task that formerly had been accomplished by the Traffic Unit.[28]

This work was accomplished by three sections. The largest, Production, led by Annie Briggs, identified codes, decoded messages, and provided clerical support. Ethel Just headed a small group of translators in the Language unit. Herman Phynes directed the last section, the B-3-b technical element charged with solving encipherments . Twenty-eight years into the future, Her man Phynes would be a GG-16, army flag officer equivalent, and NSA's first African-American office chief in the Operations Directorate. In March 1944, however, he was a subprofessional (SP)-5 cryptanalytic aide returning to government work after brief stints as an insurance salesman and a real estate agent. A Washington, D.C., native, he was a graduate of Dunbar High School and had a B.A. degree (1941) from Howard University. His earlier government service was as a clerk for the Internal Revenue Service and as a messenger and clerk in the War Department, but dissatisfied with both the pay and levels of responsibility, he left the civil service to seek work more consistent with his academic background.[29]

One other significant personnel change occurred in 1944. Bernie Pryor, the messenger for the Signals Intelligence Service, was reassigned in April 1944 to the Personnel Branch as a clerk. Undoubtedly, with the anticipation of increased hiring of African-Americans came the realization that this segment of the workforce would require support services. He thus became a human resources unit for black employees, providing a variety of employee services, including orientation briefings, information on housing and recreational facilities, and counseling on work, family, and personal financial matters.[30]

Benson K. Buffham, the administrative chief of B-3-b, had entered the Signal Corps in 1942, one year after graduating from Wesleyan University (Connecticut). In June 1999, he looked back nearly sixty years and recounted his first days at Arlington Hall and his early assignment as head of the first group of African-American cryptologists.

When I first went to Arlington Hall, I worked as a cryptanalyst (or cryppie) for about six months, working Japanese diplomatic communications. Then, a very good friend of mine at the time, Captain Mike Maloney, who was Frank Rowlett's plans and priorities officer,[31] was assigned overseas, and he recommended to Colonel Rowlett that I replace him. So I became the plans and priorities officer on the staff of B3. It was then that I was also assigned, as one of my duties, the job with the just emerging black unit. Maloney had that job before me, and when I replaced him I took that job as well. I was introduced to Bill Coffee and became the head of the unit; however, Coffee was really the operating head of the unit. I had other jobs to do at the same time. He was full-time in that job, and he was really the expert. I was the reporting chain for them, so Coffee reported to me, and I got all of his reports and reviewed them. I wouldn't say that I reviewed them all before they went out, but if they thought they had anything really significant, Coffee would show it to me first.

I was located maybe a hundred yards away from Coffee's area at a desk outside Colonel Rowlett's office. There were maybe fifteen or so people on the staff, including his secretary and personnel people. I didn't have an office. The B-3-b unit was in a separate room. Colonel Rowlett was very interested in the unit and would visit them from time to time. Bill Coffee sat right at the head and was really in charge of that area. At the time, we had a large number of black Americans working in what I would call custodial type jobs at Arlington Hall, but Mr. Coffee's unit was the only professional unit that I'm aware of.

We had the Office of Censorship in World War II, and one of my jobs was to go down to Censorship every day and collect the international material which was flowing through them, but which they weren't processing. They were only interested in things originating in or destined for the United States. Everything had to be filed with them, and they would examine material that was coming in or out of the U.S., but they wouldn't be able to examine material that was going from Tokyo, for example, to a number of foreign cities. That [international] material all fell within the realm of responsibility of the SIS. All that material had to be examined by our commercial code unit.

They [B-3-b analysts] were responsible for detecting anything that would be transpiring which wasn't routine trade. Of course there was a great deal of traffic, because we were monitoring all the international communications, particularly from Tokyo and Berlin – all the enemy traffic. But, it all had to be gone through, because you had to be sure that we weren't missing something that would be a violation of the international embargoes. Although item for item, it wasn't as important as diplomatic traffic, they performed an invaluable service by going through all that material and making sure there wasn't anything in it that would have been useful for us in the wartime effort.[32]

For several months, B-3-b continued to expand in mission and resources under Bill Coffee. In April 1945, it was assigned responsibility for exploiting the diplomatic systems of Belgium, Haiti, Liberia, and Luxembourg, though there is no evidence that this mission developed past the research stage. By June, Bill Coffee was directing the efforts of thirty people distributed over six sections, plus a secretary. Most were engaged in the major activities of code identification and decoding; researching and analyzing unknown codes; and translating.[33]

Major international trade activity resumed following the end of WWII with a concomitant substantial rise in the volume of commercial coded messages, but agency postwar personnel losses were reflected in the sharply reduced manning of B-3-b (renamed WDGAS-93K when the Signals Security Division became the Army Security Agency in September 1945). In July 1946, it was composed of fewer than a dozen people.

In February 1946, Bill Coffee was transferred to the Intercept Control Branch as the supervisor of a new typing unit which had been formed to augment the automatic morse transcription section of nearby Vint Hill Farms in Warrenton, Virginia. In the two years that he was associated with the Commercial Code unit, he had advanced from a CAF-3 ($1,620/year) to a CAF-5 ($2,430/year).[34] Replacing him as assistant O.I.C. (officer in charge) of the African-American commercial code cryptologists was his principal assistant, Herman Phynes.

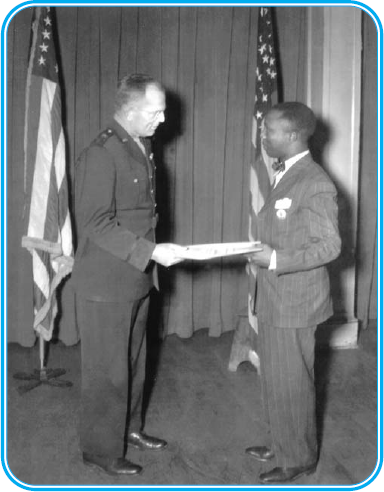

On 3 April 1946, General W. Preston Corderman, chief, Army Security Agency, presented William D. Coffee with the prestigious Commendation for Meritorious Civilian Service.

In February 1947, the practice of having a Caucasian as the nominal head of the Commercial Code unit ended with the appointment of Herman Phynes to the position of O.I.C. He was a P-2 (Professional Level −2) with an annual salary of $3,522.60.[35]

Figure 3.3. William Coffee receiving the Meritorious Service Award from General W. Preston Corderman, Chief, ASA, 3 April 1946

Although B-3-b was a unique and unprecedented organization, these early African-American cryptanalysts and translators appear to have been virtually invisible. Few former Agency employees who were interviewed and who worked at AHS during WWII had any knowledge of African-Americans in professional positions; most did not even recall seeing African-Americans on the campus.