The modern organization cannot be an organization of "boss" and "subordinate": it must be organized as a team of "associates." | ||

| --Peter Drucker[268] | ||

Imagine a warm summer's evening. A young man has invited a young woman on a first date. They have been to dinner at a wonderful restaurant. They have enjoyed each other's company. They have laughed at the same jokes. They have enjoyed the same food. As they learned about each other, they experienced the wonder of being on a mutually exhilarating journey. Now the evening is about to end with a lingering kiss.

Then suddenly the young man pulls out his wallet and says, "I've had a wonderful evening. How much do I owe you? Will a hundred bucks cover it?" She slaps his face, and the relationship is over.

Suppose, alternatively, that instead of offering the young woman a hundred dollars, the young man had said, "I'm the boss now. Here's what you have to do over the coming weeks; otherwise I'll be terminating this relationship." To which, the young woman replies: "Save your breath, buster! We're terminating it right now!"

In either case, the young man has made a social category mistake. The social category of dating exists in what is sometimes called the gift economy of social norms. There's give and take, but actions are not seen as having a market price or determined by one person being the boss of the other.

Suggesting that the young woman's actions have a dollar value instantly moves the relationship out of dating and into the world of market pricing. Or if the young man asserts that he is the young woman's boss, he will have inexplicably turned the date into an unpleasant boss-subordinate relationship. Either way, the damage is done. She is not the kind of woman who sells her company for money or takes orders from her boyfriend. The social relationship is over.

Behavioral economist Dan Ariely points out in his book Predictably Irrational that we live simultaneously in different worlds: one where social norms prevail, another where market pricing determines the rules, and still another where authority ranking prevails.

The social norms of the gift economy are wrapped up in our social nature and our need for community. They are usually warm and convivial. The world of market pricing is very different. There's nothing warm and convivial about it. As Ariely points out, "The exchanges are sharp-edged: wages, prices, rents, interest, costs and benefits.... When you are in the domain of market norms, you get what you pay for—that's just the way it is.[269]

In relationships based on authority ranking, superiors are accepted as having the right to direct and control the activity of subordinates. The relationship may be anywhere on the spectrum from warm and convivial to harsh and sharp-edged. Pulling rank and asserting pure authority can quickly turn a convivial hierarchical relationship into one that is harsh and sharp-edged.[270]

Table 10.1. Types of Social Relationships

Authority Ranking | Market Pricing | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Work | Everyone pitches in and does what he or she can, without keeping track of inputs. Tasks are the collective responsibility of the group. | Superiors direct and control the work of subordinates and control the product of subordinates' labor. | Work for a wage calculated as a rate per unit of time or output. |

How decisions are made | Group seeks consensus, unity, the sense of the group. | Superiors make decisions by authoritative fiat or decrees. | The market decides, governed by supply and demand. |

Strengths | Energy, enthusiasm | Decisiveness | Objectivity |

Weaknesses | Difficulty reaching closure | Inflexibility, lack of responsiveness | Lack of collaboration |

Examples | Families, communities, sports teams, high-performance teams | Military, hierarchical bureaucracy | Labor unions, stock markets, commodity trading |

When social norms, market norms, and authority ranking operate in separate domains, life ticks along in a predictable fashion. But things get tricky when these three interact.

In 1992, anthropologist Alan Fiske suggested that social norms (which he called communal sharing), authority ranking, and market pricing are three of the elementary social relationships that dominate human relationships in all cultures (Table 10.1).[271]

In dealing with their employees, managers are today necessarily operating simultaneously in all three worlds: market pricing, authority ranking, and social norms. They can't avoid being in the world of market pricing because work necessarily involves remuneration. They can't avoid being in the world of authority ranking, because someone has to take legal decisions on behalf of the organization. And they can't avoid being in the gift economy of social norms, because they need the workers to offer the gift of their energy, ingenuity, and spirit to accomplish the task of continuous innovation.

The gift can't be commanded because that leads to grudging implementation. Nor can it be bought. If the organization tries to buy it, the organization risks getting the equivalent of the slap on the face that the young man received from the young woman when he offered her money in return for the evening.

The challenge for managers is that in trying to elicit the energies, imagination, and creativity of their workers, they need to be predominantly in the world of social norms, against a history of relationships dominated by market pricing and hierarchical ranking.

The tensions among these three worlds are significant. The hard, sharp edges of money-based discussions or the sneer of cold command can slice through the warm, convivial world of social norms like a knife and kill it on the spot. How can managers overcome the baggage of market pricing and authority ranking and communicate in the world of social norms?

Managers can't treat workers like friends and family one moment and then in an impersonal, authoritarian way or a bargaining mode the next when this becomes more convenient or profitable. This is not how the world of social norms works.

The world of social norms is fragile. To be operative, the norms have to be front and center at all times in the relationship. That's because the social norms of the gift economy are allergic to communications that smell of market pricing or hierarchical ranking. Studies show that the mere mention of money or pulling rank is enough to kill the warmth and conviviality of a social relationship. Even thinking about money is enough to make people less willing to help others.[272]

Coping simultaneously with the conflicting norms of these three different worlds isn't easy, but the issue isn't unique to the workplace. For instance, if the young man we imagined at the start of the chapter had not mentioned the hundred dollars and his relationship with the young woman had blossomed into love and marriage, then money issues would inevitably have entered into the picture. How much money does each person bring to the marriage? Do they pool their money or keep separate accounts? Who earns money? Who pays for what? If it's a warm, mutually sharing marriage, these issues will tend to be resolved in a friendly, respectful fashion, subordinated to the overriding convivial relationship of social norms.

But if money questions dominate the marriage, so that arguments about money and who owes whom for what become predominant, with constant haggling over prices and exchanges, then all sharing and giving will go out the window. It will become a tense, market-priced business arrangement, in which divorce may be the eventual outcome.

If the young man had not pulled rank on the young woman and the relationship had continued into love and marriage, questions of authority would also have emerged. Within the marriage, who has the power to decide what? Are decisions taken jointly, or is one person in charge? Is this true for all subjects, or do they have different authority in different areas? If the relationship is warm and mutually sharing, then these issues will be resolved in a friendly, respectful fashion, subordinated to the overriding social norms.

The communication challenge for managers is thus not unique, but it is significant. Clearly managers will not succeed in eliciting their employees' talents by pulling rank through top-down communications, sending messages, or merely telling people what to do. Nor will they succeed by offering to buy people's enthusiasm and spirit. These are gifts that can't be bought.

Communication in radical management entails a shift from the model of, "I've got something to tell you and I'm hoping you're going to see it the way I see it, and if you do that, I'll pay you for it," into, "I've got a spark. Let's build a fire together." In effect, radical management uses an interactive mode of communication that breeds on the connections among people.

Interactive communication is the usual mode of communication in the world of social norms. It is characterized by authentic narratives, open-ended questions, and conversations. Just as in a flourishing marriage, questions of money and power may be present. But if the communication is interactive and genuinely respectful, the social norms of a healthy reciprocal relationship will predominate.

Authenticity is central to radical management. At its simplest level, it means that words, beliefs, and actions are consistent.[273] Spelled out more fully, it means that because radical managers know who they are and what they stand for, others come to know them and respect them for that. Because they are attentive to the world as it is, their ideas are sound. Because they level with people they are speaking to, they are believed. Because their actions are consistent with those values, their values become contagious, and others are keen to share them. Because they listen to the world, the world listens to them. Because they are open to innovation, happy accidents happen. Because they bring meaning into the world of work, they are able to get superior results.

This is the ideal of authenticity. This is what a good manager looks like, feels like, speaks like, and acts like. In this way, we can recognize genuine authenticity when we see it and not be confused into thinking that an all-knowing fast-talking tough guy, like Robert McNamara, is a good manager.

As to why the people heading organizations today don't always correspond to this ideal, there are various reasons. At the outset, the people who aspire to become heads of organizations require a certain amount of boldness and ambition. Moreover, the selection process tends to favor those who put on a good front. The events that happen to people as they try to attain their goal and get ahead of their competitors for power can also reinforce the dark side of their characters. Once they attain their goal, the seduction of power itself has the potential to corrupt. Yet behind all these practical reasons lies a certain conception of what it is to be a good manager. Business schools and textbooks tend to reinforce the traditional notion of someone who knows how to play hardball and takes no prisoners.[274]

Radical management requires managers at all levels who know how to connect with and understand others and who are willing to face up to and take responsibility for the consequences of their actions. The concept of authenticity needs to find its way into business schools, textbooks, and selection processes. Attention needs to be paid to obvious gaps between what organizations say they are doing and what they are actually doing. (See Chapter Four.)

A key ingredient of authentic communication is narrative. It's no accident that those who have been successful in propagating the practices of radical management in software development, like Jeff Sutherland, Ken Schwaber, and Mary Poppendieck, are excellent storytellers.[275] In many ways, they exemplify the interactive and seriously playful mode of communication that is crucial in generating and sustaining the high-performance teams of radical management.

Leadership storytelling can be learned. It is not about acquiring something totally new, but rather applying something we already know how to do for constructive purposes in an organizational setting.

As I explained in my books, The Leader's Guide to Storytelling and The Secret Language of Leadership, we all start spontaneously telling stories at the age of two and go on throughout our lives communicating through stories.[276] In organizations, we have gotten in the bad habit of communicating through abstractions, leaving people bored or confused. Storytelling is our natural language. People naturally think in stories, dream in stories, plan in stories, and make decisions in stories. Communicating in story is easier for both speaker and for the listener.

To illustrate what I mean by an interactive mode of communication, let's examine what happens in one of the most frequent and mundane of management interactions: a talk to a group of people. Let's compare the communications of a traditional manager with that of a radical manager.

The traditional manager comes to the meeting with a message to impart. The presentation is typically an abstract talk that proceeds independently of the listener. Without noticing whether anyone is really paying attention, the manager announces his or her idea—perhaps yet another reorganization—the premises of which are entirely management's. Decisions have already been taken. The manager assumes that the audience will accept what he or she is about to say because of his or her hierarchical position.

The audience's spontaneous reactions—smiles, frowns, applause, or disapproval—are essentially irrelevant distractions to what the manager is saying. The audience never enters the picture as an active participant. Even when they are allowed to ask questions or make comments, it is expected that the comments and questions will be safely contained within the confines of the manager's agenda. The success of the communication is seen as depending on whether the manager has been able to transmit the message.[277]

Traditional managers speak to employees as employees, and power is the currency of the communication. These managers present themselves as the superior of the subordinates, although out of feigned politeness, traditional management refrains from calling subordinates "inferiors."

In reality, the subordinates may be superior to their "superior" in many respects: knowledge, skills, courage, integrity, or something else. As a result, traditional managers are continuously involved in exaggerations and mystifications to preserve a facade of superiority. It is in this facade that traditional managers place their hopes of getting things done. Yet in the world of knowledge work, it is perceived for what it is—a facade. As a result, if traditional managers mention or allude to social norms in such a setting, they sound fake because the relationship is hierarchical.

For radical managers, the situation is different. These managers don't come to the meeting empty-handed. They come with ideas—perhaps to introduce the principles of radical management, but also to interact with the audience, learn from their viewpoints, and discover new truths. The interaction is a conversation, not a telling.

Even before the presentation has begun, radical managers demonstrate openness. They might welcome the audience individually or physically acknowledge their presence. They do this because it's difficult to be unresponsive to someone who is actively signaling responsiveness and reciprocity.

A radical manager, on beginning to talk, recognizes that the audience is not necessarily paying attention, and so takes active steps to get attention. As discussed in The Secret Language of Leadership, the talk begins with things that are already of interest and relevance to the audience, before moving on to the idea to be discussed.[278]

Once the audience is paying attention, the radical manager shifts, as discussed in The Leader's Guide to Storytelling, to springboard stories of successful implementation of the idea under discussion. The stories—simple, true, positive, and perhaps a little unexpected but still plausible—enliven the audience's interest and are easy to understand.[279]

The reactions of the audience to these stories are central. They represent essential markers as to whether and how the narratives are resonating and as to how the manager should proceed from that point.

The radical manager adjusts what is said in light of the audience's reactions, and the audience sees that. This prompts new reactions from them, which leads to new adjustments by the manager. The manager is aware of the audience just as the audience is aware of the manager.

The radical manager uses narratives to elicit responsiveness. The responsiveness of the audience is contagious. Each listener is aware of the reactions of other listeners to the manager, so if other listeners are laughing, there is a tendency for every listener to laugh.

When the radical manager invites reactions from the audience, the responsiveness of the presentation to the listeners will have created a mood of possibility. It becomes plausible for the audience to offer their own stories, which may have different underlying assumptions from those of the manager. The discussion can broaden into areas that might otherwise be impossible to broach. As a result, what begins as a simple talk by the manager to the subordinates can suddenly become an opportunity for new ideas—new truths that fuse the inputs of multiple participants.

The talk I have just described would be only one part of a manager's busy day, which may have scores of such interactions. By being open and interactive with all the people who fill the day's calendar, the radical manager is not only communicating ideas but also opening up new horizons and possibilities and encouraging collaboration.

The stories that the radical manager has elicited in the minds of the listeners are in some ways more important than the manager's own stories. These stories are now owned by the listeners. They represent the embryonic plans of action that the audience will take. If the stories are positive and energizing, the implementation will be positive and energetic too.

The radical manager communicates as one human being to another. Hierarchy is present but in the background. Appeals to the audience to contribute with spirit and enthusiasm sound authentic and appealing. The relationship is interactive as is natural and normal in the world of social norms.

By contrast, the traditional command-and-control manager spends a day full of encounters that end in adversarial, tension-filled, power-driven outcomes, with few new opportunities emerging. On the surface, it is a day of apparent order and focus, with the traditional controlling manager "winning" most of the encounters as a result of hierarchical power. But the audience's apparent submissiveness is deceptive. In fact, the listeners' minds are filled with stories that are negative and cynical. Implementation will be difficult because the listeners will withhold the gift of enthusiastic support for change and refrain from fully engaging in the workplace.[280]

A key ingredient in the communications of radical management is the concept of conversation—a dialogue between fellow human beings. The relationship between the speaker and the listener is symmetrical and reciprocal. Communications proceed on the assumption that the listener could take the next turn in the discussion.

In organizations, the differences in hierarchical status between the speaker and the audience may be vast. The speaker may be a boss talking to subordinates or a subordinate talking to a higher-level boss or bosses. In radical management, the speaker ignores these differences in status and talks to listeners as one person to another. In this way, the radical manager slices through the barriers that separate individuals.

By contrast, the command-and-control manager speaks in abstractions and exploits differences in status and adversarial relationships. Thus, when the manager asserts, "We must do X," the listeners' options are to accept or reject the proposition. If they accept it, they are submitting to authority. If they reject it or argue about it, they are rebelling against authority. Either way, they are in a hierarchical, adversarial relationship. The risk of the organization's losing the precious gift of employees' energy and enthusiasm is significant.

When a radical manager converses in narratives, there is no issue of submission or rebellion. The listeners don't need to accept or reject the narrative because the radical manager and the audience live the story together. It is a mutually shared experience, something in which the audience has actively participated. The normal response is neither acceptance nor rejection but rather to tell another story. It might be a story in the same vein, or it might be prefaced by, "I have a different take on that!" followed by a story that reflects another point of view. Either way, one story leads to another. It's not a normal response to say, "That story is right" or "That story is wrong." A story is neither right nor wrong. It simply is. In this way, storytelling is naturally collaborative.

Over a quarter of a century ago, management theorist Charles Handy noted the tendency in organizations toward bigness and consistency. According to Handy, "Size...brings formality, impersonality, and rules and procedures in its train. There is no way out of it. When someone cannot rule by glance of eye and word-of-mouth because there are just too many people, he has to lean on formal systems of hierarchy, information, and control."[281]

And yet there is a way out. The key is figuring out where to put the boundaries and controls. Radical management doesn't abandon boundaries or controls. In some areas, it is more open and creative, and in others, it is even more rigid and structured than traditional management. Thus, it insists on the goal of delighting clients, on self-organizing teams, on setting priorities before work, on iterative patterns of work, on the team's taking responsibility for what is to be done, on delivering value at the end of each iteration, and on accountability for the outcome. But it insists on these elements in order to create an open space where self-organizing teams can flourish. It uses structures and boundaries to prevent bureaucracy from infecting the work itself.

The living part of the organization thus coexists with the structures because they enable creativity. We see examples of this phenomenon everywhere. In nature, we see the fantastic diversity generated by a few basic structural elements: no more than a hundred varieties of atoms and a couple of primary colors lead to a universe of infinite beauty and diversity. In the twelve notes of the musical scale and the twenty-six letters of our alphabet, we see how these rigid structures have enabled the creativity of music and literature. Without structure, there is nothing for creativity to build on. Radical management thrives on structure that enables, rather than restrains, creativity.

Narrative modes of communication are extraordinarily relevant in dealing with the challenge of being rigid in some areas and open and creative in others. Suddenly the tasks of getting people to understand and implement complex new ideas, working together and sharing knowledge to generate enthusiasm and flair become feasible.

In The Leader's Guide to Storytelling and The Secret Language of Leadership, I have explained in detail how to use the power of storytelling to handle the various challenges that leaders face, including sparking change, communicating who you are, enhancing the brand, getting people working together, transmitting knowledge and values, and leading people into the future.

The radical manager uses those practices to ignite support for the other six principles of radical management, particularly:

Using leadership storytelling to inspire support for the goal of delighting clients

Using conversations to create and sustain self-organizing teams

Communicating the goals and progress of work done in client-driven iterations through user stories

Modeling truthful communications that support and reinforce radical transparency

Coaching teams to get on a trajectory of continuous improvement so that they become more productive than the norm and find work deeply satisfying

Practice #1: Use Authentic Storytelling to Inspire a Passion for Delighting Clients

For most organizations, radical management entails a hefty change agenda—often a fundamental shift in culture. As I explained in The Leader's Guide to Storytelling, this won't happen without compelling leadership storytelling—springboard stories about how other organizations have done it and stories about how it is already happening within the organization. These stories can inspire other managers and staff to try it out.

Practice #2: Focus the Goals of the Team on User Stories

Radical management involves a shift from seeing teams and organizations as entities that produce things (goods and services) to that of groups of people who delight clients sooner, more often, and more profoundly. This can happen only if the team knows the client's story and hence knows what might delight the client (see Practice #8 in Chapter Six).

Practice #3: Deploy User Stories as Catalysts for Conversation

As discussed in Practices #8 to #12 in Chapter Six, stories aren't artifacts or instructions or commands. They are opportunities to conduct a conversation between the client or client proxy and the people doing the work. The object of the conversation is to deepen understanding as to what might delight the client.

Practice #4: Use Stories to Focus Teams on Achieving High Performance

Why do some self-organizing teams evolve into high-performance teams, while others flounder for months or even years? Getting the context right is a big part of it. But even when the context is right, it still may not happen. Sometimes it's a matter of having the right mix of skills. But sometimes it's also the team's internal dynamics.

Much hogwash has been spoken and written about "motivating" individuals and teams through the use of incentives and disincentives. The reality is that carrots and sticks don't motivate knowledge workers.[282] Instead, skilled leaders find what drives people into action and discover ways to connect that to the goals of the team. The idea is to identify what puts people in motion and then get them more of that.

Ultimately the evolution of self-organizing teams into high-performance teams depends on team members' mutual respect and trust. When people have this kind of respect, they feel they have the support of others in the group. They view the group's resources, knowledge, perspectives, and identities to some extent as their own. They feel as though they have new capabilities and begin to include others in their concepts of themselves. They feel a sense of exhilaration as they learn new things from and about their partners. In a sense, their sense of self expands. They become larger persons.

Aristotle wrote about this phenomenon in terms of the concept of philia. This is usually translated as friendship, but it is more than mere liking or friendship. It connotes the passion associated with love, but without the sexual connotation. High-performance teams routinely talk about their relationships as a form of love.[283]

It is also admiration, but it's not a mutual admiration society: these relationships have a constructive frankness because the participants care enough to say the things that mere acquaintances wouldn't. The team members discover what is wonderful in the other person, but the quality is not preexisting: it is mutually created. In effect, it is a deep appreciation for the character of the other person.

In order for the team members to reach this level of respect, they have to know each other more deeply than the superficial relations of the hierarchical bureaucracy where one leaves one's personal identity at the workplace entrance. They need to know the stories of the people they are working with.

Practice #5: Use Stories to Help Team Members Understand Who They Are

One reason that the team members may not know whether they can trust or respect the other members is that the other team members themselves don't have a clear image of who they are, and so are unable to project a personality that is fit to be trusted. In such situations, as I explained in The Leader's Guide to Storytelling, teaching the team members to learn how to craft and perform the story of who they are can enable them to come to terms with what sort of person they are and communicate that to the other members of the team.

Practice #6: Use Stories to Inspire Group Philia

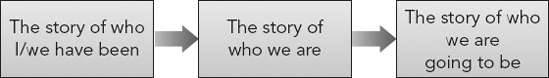

The classic way in which groups have been inspired to work together is a narrative pattern that is as old as the ancient Greek historian Thucydides and as modern as the political campaign of Barack Obama (Figure 10.1).[284] Having the group craft and perform this combination of stories communicates to both themselves and others what they have in common and why they might evolve into a high-performance group.

The first story, the story of "who I or we have been," establishes an emotional connection between the speaker and the audience. The second story, of "who we are," reminds the group of the common elements that already bind them together. The third story, of "who we are going to be," generates a new story in the minds of the listeners about how they are going to act together in future.

It is the alignment and narrative coherence of the three stories that makes communication compelling. The present emerges inevitably from the past, and the future flows seamlessly from the present.

Practice #7: Stimulate the Muscle Memory of High-Performance Teams

The underlying idea of radical management—energetically collaborating with others to do the very best you collectively can—is strange but also familiar. Almost all of us have had the experience of being in a group that is highly productive and vibrantly alive at one time or another. This isn't the invention of a management consultant. It's something we already know. The experience has probably existed since time immemorial, when our hunter-gatherer forebears were living in caves and fighting off wolves.

If we take the time, we can refresh that memory and recreate it. That earlier experience was a premonition of the future. If we can recall that earlier experience, it can be an easy mental leap to a realization of how easy and fruitful it can be to recreate it today.

One way of drawing on that memory is to have the team members tell each other stories of their own experiences of high-performance groups that they have experienced in the past. This may enable the group members to start to see each other as people who have had such experiences. In doing so, they are seeing the other members of the team when they have been at their best. The process can give rise to the implicit question: If we have all been in high-performance teams in the past, why can't we get into this mode now?

Practice #8: Tell Springboard Stories of Other High-Performance Teams

To encourage memories of high-performance teams, a leader might tell stories about successful high-performance teams in other similar organizations, with the objective of stimulating the narrative imaginations of the team members with the thought, If people like that, who are very similar to us, could do it, why not us now?

Practice #9: Practice Deep Listening to Each Other's Story

Deep listening of the stories of the other members of the team can help people become more familiar with those they are working with. Managers can help create safe spaces where such deep listening can take place.

On the surface, these may seem like exercises. But when they work well, the participants lower their social guard. They make themselves vulnerable and learn about each other's hopes and fears. They discover what's wonderful in each other. They are suddenly looking at themselves through the admiring eyes of others, and vice versa. They can see themselves as more noble, generous, and open and begin to act with them in these ways. They become "new people."

Winning the mutual respect that generates high performance is not risk free. Those who recognize that radical management is something worth fighting for, taking risks for, will also see that not risking anything is an even greater risk.

Practice #10: Give Recognition for Identifying Impediments

Radical management is about systematically identifying and eliminating impediments to improved performance. Team members are not just encouraged to suggest improvements; they are required to identify impediments even when no solution is in sight.