Chapter 11 An End-to-End Lean Product Case Study

Now that I've described each of the six steps of the Lean Product Process in detail, I want to walk through a real-world case study to further solidify the concepts I've covered. I've shared this example in talks and workshops that I've given, and many participants have told me how helpful it is to see the application of the Lean Product Process with an end-to-end example.

MARKETINGREPORT.COM

One of my clients asked me to help define and evaluate a new product called MarketingReport.com. This client's company had a successful consumer web service and was contemplating a new web service to pursue a potential market opportunity. I worked closely with two company executives and a UX designer on this project.

The new service idea centered on a widespread customer problem associated with direct mail—namely, that many people who receive direct mail do not find it valuable and consider it a nuisance. The executives had some insight into the direct mail industry and knew that the mailings were targeted based on marketing databases that profiled customers. For example, you might receive an unsolicited coupon for cat litter from a certain pet store chain because a marketing database somewhere indicates that you have (or are likely to have) a cat in your household.

The idea was to solve this problem by providing a product that gave customers transparency into the profile that marketers had built of them and empower them to make that profile more accurate. So, if I don't own a cat but own a dog, I could correct the marketing databases so that I receive coupons for dog food instead of cat litter. The executives saw parallels with the credit industry. Every day, thousands of credit-related decisions are made based on people's credit scores. Before the advent of credit reporting services, consumers didn't have much visibility into why they had the score they did; their credit worthiness was based on “behind the scenes” data about their credit history. They might therefore get declined for a loan and not know exactly why. Inaccurate data about their past payments—such as a loan payment reported as unpaid that actually wasn't—could negatively impact them. By providing transparency, credit-reporting services enable customers to see the data behind their credit rating and correct any inaccuracies. MarketingReport.com would do for personal marketing data what credit reports had done for personal credit data.

The initial idea was to provide the service for free and to monetize the marketing data that the service generated. By giving customers access to the data, and the ability to correct inaccuracies and provide additional information, we planned to build a collection of rich and accurate profiles. Therefore, it was critical to define a service with which customers would want to engage.

STEP 1: DETERMINE YOUR TARGET CUSTOMERS

You'll recall that Step 1 of the Lean Product Process is to identify your target customer. We agreed at this early point that this would be a mainstream consumer offering. Steps 1 (target customers) and 2 (customer needs) are closely related, so we didn't narrow our target market hypothesis any further than mainstream consumers at this point. We knew we would refine our target customer hypothesis as we gained additional clarity about the customer benefits we could deliver.

STEP 2: IDENTIFY UNDERSERVED NEEDS

We then started working on Step 2: identifying underserved customer needs. Both executives agreed that the service's core benefit was empowering customers to find out what “they” (the direct marketing databases) know about the customer. However, there were a lot of different ideas for what the service would do beyond that core benefit. So we brainstormed a long list of different potential customer benefits that our service could deliver, which included these five ideas:

- Discover money-saving offers of interest to me

- Reduce the amount of irrelevant junk mail I receive

- Gain insights into my spending behavior

- Meet and interact with other people with similar shopping preferences

- Earn money by giving permission to sell my marketing-related data

To identify which customer benefits we wanted to pursue, we came up with a set of evaluation criteria, some of which were positive and others negative. We evaluated each benefit on the following criteria:

- Strength of user demand (+)

- Value of marketing data obtained (+)

- Degree of competition (−)

- Effort to build the v1 product (−)

- Effort to scale the concept (−)

- Fit with the company's brand (+)

- Amount of reliance on partners that would be required (−)

We scored each customer benefit on these criteria based on our estimates, which allowed us to weed out less appealing ideas. Customer benefits 1 through 4 from the above list were considered worth further consideration.

STEP 3: DEFINE YOUR VALUE PROPOSITION

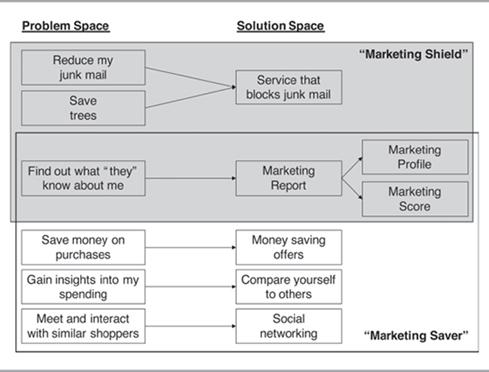

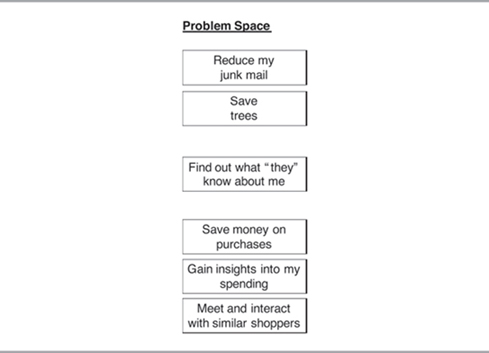

At this point, I wanted to nail down which benefits were in scope versus out of scope for our envisioned product so we could solidify our value proposition. So I led the executives in an exercise to map out the problem space for our product, shown in Figure 11.1.

You can see that I grouped related benefits together. We had our core benefit of finding out what “they” know about me (in the middle). A second cluster of benefits (at the top) included reducing junk mail and saving trees (being friendly to the environment). A third cluster of benefits (at the bottom) included saving money on purchases, gaining insights into my spending, and interacting with similar shoppers.

I felt that the three clusters on this problem space map were too much to bite off in a single product. Plus, it wouldn't feel coherent if we tried to build one service that addressed all these benefits; the top cluster and bottom cluster were very different. Additionally, while one executive liked the top cluster of benefits more, the other preferred the bottom cluster. I thought they were all good ideas, so I recommended that we pursue two distinct product concepts, each with its own value proposition. The first concept, dubbed “Marketing Shield,” would consist of the top two clusters. The second concept, dubbed “Marketing Saver,” would consist of the bottom two clusters. By using this approach, each concept included the core benefit of “find out what ‘they’ know about me” but wasn't too broad in scope. The executives agreed.

FIGURE 11.1 Initial Value Proposition for MarketingReport.com

In Chapter 5, I recommend that you articulate your product value proposition using the Kano model to classify each benefit as a must-have, performance benefit, or delighter, while taking your competition into account. We viewed the core benefit of “find out what ‘they’ know about you” as a delighter because this type of service didn't exist. We knew that there were other products in the market that gave customers money-saving offers; so we viewed that as a performance benefit. Similarly, although social networking products existed, they weren't necessarily focused on shopping; so we viewed that as a performance benefit as well. We weren't aware of other products that let you compare yourself financially to others, so we viewed that as a delighter. On the Shield front, we viewed reducing junk mail as a delighter. There were plenty of other ways to be environmentally friendly, so we viewed “save trees” as a performance benefit.

STEP 4: SPECIFY YOUR MVP FEATURE SET

Now that we had the value proposition for each of our two concepts, we started talking about the solution space and brainstormed features that would deliver those benefits. See Figure 11.2 for the features that we settled on for each product concept.

The main feature for the core benefit of “find out what ‘they’ know about me” was a marketing report containing a collection of marketing-related information about the user built over time. The report originates from data about a customer's purchases and their responses to surveys, mailings, and phone calls. The idea was to provide customers with transparency into the data that the marketing databases contained about them.

Two key components we envisioned for the marketing report were the marketing profile and the marketing score. The profile was based on a set of consumer segmentation clusters used by direct marketing firms. Each cluster has a catchy, descriptive name—like “young digerati,” “soccer and SUVs,” or “rural retirees”—and is based on key demographic data such as age, marital status, home ownership, children, and zip code. Marketers use these profiles to target relevant offers to people.

We were inventing the idea of a marketing score from scratch. It was intended to be analogous to a credit score—a single number that represents your overall credit worthiness. In the same way, the marketing score was a single number that represented your overall attractiveness to marketers. A higher credit score garners you a better interest rate; a higher marketing score would garner more and better money-saving offers. We identified several factors that would go into determining a customer's marketing score.

Turning to the bottom cluster, the main benefit was money-saving offers. The idea was that the customer could identify what types of products and services interested them and would then receive relevant money-saving offers. We would basically be playing matchmaker between consumers and companies who wanted to promote their products. The feature would consist of a user interface where the customer could specify their preferences, a marketplace of vendors, matchmaking logic, and delivery of the offers via the website and email.

The second feature in the bottom cluster was comparing yourself to others. The idea was that the customer could compare their spending patterns with similar customers to see if they are spending more or less on certain areas such as dining, clothing, entertainment, and so forth. Gaining this insight would allow them to modify their spending behavior as they saw fit.

The third feature in the bottom cluster was the ability to interact with similar shoppers. The idea was that customers might discover new products or learn about great deals from similar shoppers. Social networking was relatively hot at the time and we wanted to experiment with some social functionality related to online shopping.

The feature in the top cluster was a service that would block junk mail. This addressed both the “suppress junk mail” and “save trees” benefits. The idea was that we would start out with a “Wizard of Oz” MVP by manually filling out and submitting “do not mail” requests on behalf of customers. We would eventually transition to a more automated solution if warranted.

STEP 5: CREATE YOUR MVP PROTOTYPE

With our feature set defined, it was time to move on to Step 4 to bring these features to life with some design artifacts. We knew that we wanted to test design artifacts with customers in person before we did any coding, so we decided to go with medium fidelity mockups. The mockups had enough visual design—coloring, fonts, graphics, and styling—to effectively represent the product to users, but we didn't worry about making them pixel perfect.

We started by thinking through and defining the product's structure (information architecture) and the flow of the customer experience (interaction design). The customer would start by receiving an email describing the service. The email's call to action was “see your marketing report” with a link to a landing page, which further described the service and had a key conversion button labeled “see report.” Each customer was assigned a unique code that was included in the email. After clicking the “see report” button, the customers were taken to the “verify information” page. This page contained a form listing their name, address, marital status, household income range, and other key demographic information. This page showed customers the information contained in marketing databases and allowed them to correct any inaccurate information. After clicking the “continue” button on this page, they were taken to the Marketing Report page.

The Marketing Report page was the main page of the product after going through the onboarding flow. It was a dashboard of modules that enabled us to use the same general design for the two product concepts by just swapping out different modules for the “Marketing Shield” versus the “Marketing Saver.” For both product concepts, the Marketing Report dashboard included modules for the Marketing Profile and the Marketing Score, since these were the core feature ideas. The remaining two modules would vary by concept. The Marketing Shield version had a “block junk mail” module. The Marketing Saver version had modules that covered money-saving offers, comparing yourself to others, and social networking.

The Marketing Report page was the hub from which customers would navigate. They could click on each module to drill down to a more specific page dedicated to that topic. For example, the page dedicated to money-saving offers allowed the customer to select which types of products and services were of interest to them, such as vacations, electronics, and so forth. The page dedicated to “block junk mail” displayed a list of different categories of direct mail and allowed users to select which ones they no longer wanted to receive. That page also included an upsell offer to “Marketing Shield Premium,” a paid service that would further reduce the amount of junk mail you received and provide greater privacy for your marketing profile data. With the exception of this upgraded offering, the “Marketing Saver” and “Marketing Shield” services were intended to be free to customers.

STEP 6: TEST YOUR MVP WITH CUSTOMERS

With our mockups done, it was time to proceed to Step 5: testing with customers. At this point, we needed to revisit and refine our target customer definition before we started recruiting. Since we had two distinct MVPs, each with its own value proposition, we had to define the target customer for each. The target customers for the Marketing Shield remained mainstream consumers, but we refined our definition to be people who highly valued their privacy. The target customers for the Marketing Saver also remained mainstream consumers, but we refined our definition to be people who place a lot of value on saving money on their purchases and getting good deals.

Recruiting Customers in our Target Market

We decided to use in-person moderated testing, and I moderated the sessions. In the interest of collecting data more quickly, I spoke with two or three customers at a time instead of one-on-one. I selected a local research firm to recruit customers for us, and they used a screener that I created to qualify customers. Let's walk through the screener questions I used and the rationale behind them.

First off, I wanted the research subjects to be employed full-time (at least 30 hours per week) to ensure that they were in our target market. Many unemployed or retired people participate in market research because they have ample free time, but they wouldn't necessarily be representative of our target market. I required at least a high school diploma and recruited a balance of education levels, consistent with our mainstream audience. I also recruited for a mix of household incomes with a minimum of $40,000. They also had to have a computer in their household and use the Internet at least five hours per week (since our service was going to be delivered via the web). We also wanted to make sure they had purchased a product on the Internet in past six months (so that they would be comfortable paying online for our service). I viewed all those requirements as ensuring the person was a mainstream, working adult in the target market for web-based services.

Next, I had to decide how to ensure the person was in the target market for the particular concept (Saver or Shield). I decided to use past behavior as an indicator for fit with our two target markets. Since the distinct benefit of Marketing Saver was saving money, for that group I asked about several different money-saving behaviors:

- Have you used three or more coupons in the past three months?

- Are you a Costco member?

- Have you made a purchase on eBay in the past six months?

- When making purchases, do you usually or always spend time researching to make sure you've found the lowest price?

The respondent earned one Saver point for each “yes” response. We considered anyone with two or more Saver points to be in the Saver target market.

Similarly, since Marketing Shield was about privacy and security, I asked that group about several behaviors related to those topics:

- Have you ever asked to be put on the “do not call” list?

- Do you have caller ID blocking?

- Do you own a paper shredder at home?

- Have you paid for antivirus software in the past six months?

Respondents earned one Shield point for each “yes” response—and we considered anyone with two or more Shield points to be in the Shield target market.

We did not select respondents that failed to qualify for either of the two segments. A small number of respondents qualified for both segments, since the criteria were not mutually exclusive (i.e., it is possible to care about saving money and about privacy).

Once respondents qualified for the research, we also asked them for their address, age, marital status, number of children, home ownership, household income, education level, occupation, and ethnicity. We used this information to create a personalized version of the “verify information” page mockup for each customer. We also used this information to tailor each customer's Marketing Profile to the matching segmentation cluster. This personalization of the mockups allowed us to develop a much more realistic experience for customers in our tests than we'd be able to do using a generic page and asking them to use their imagination. In fact, most customers expressed surprise when they first saw this page: They asked, “How did you get all this information?” We successfully provoked the realization in customers that “they” (the marketing databases) really do know a lot about you, which was the core value proposition for MarketingReport.com.

We worked out the days and times when we would hold research sessions. Since we were talking to people who worked full-time, we selected times later in the day after working hours (6 and 8 P.M.) to better accommodate their schedules. One common mistake companies make is to force research sessions during their working hours for their convenience. If it's not a problem for your target customers to meet at that time, that's fine. But meeting during the workday is inconvenient for most working adults. As a result, you can skew the type of customers who show up to your research to the point of not being truly representative of your target customers.

To make scheduling more efficient, we asked respondents when we screened them to let us know all of the session times that they would be able to attend. Once we had all this info for all the respondents, scheduling them later to fill all our time slots was easy. The research firm successfully recruited customers for all our slots.

User Testing Script

While the recruiting was taking place, I created the script I planned to use in moderating the user testing. Each session was 90 minutes long. Here is the high-level outline of my user testing script showing the time allocation:

- Introductions and warm-up (5 minutes)

- General Discovery questions (15 minutes)

- Direct marketing mail

- The data about you that companies have

- Comparing yourself to others financially

- Concept-specific questions (45 minutes total)

- Discovery questions related to concept's main theme (10 minutes)

- Feedback on concept mockups (35 minutes)

- Review: What did you most like/dislike about what you saw? (5 minutes)

- Brainstorm: What would make the product more useful/valuable? (10 minutes)

- Feedback on possible product names (10 minutes)

- Thanks and goodbye

To test out my script and our mockups, I ran a pilot user test first with someone from the company before the first session with real customers. Based on the pilot test, we made some tweaks to my questions and to the mockups. Then we were ready to go!

On each of three evenings, I moderated two sessions with three customers scheduled for each. Half the sessions were for Marketing Saver and half were for Marketing Shield, so nine customers were scheduled for each concept. We ended up having two no-shows, so we spoke with eight customers for each concept. As I mentioned, we personalized the data in the mockups for each customer. Because this was before the days of clickable mockups, I printed out each mockup—one per page. I put them in a stack in front of each customer in the order that they would be seen. I followed my script, and as the customers navigated through the mockups, I flipped the pages.

What We Learned from Customers

The sessions went well. The customers were engaged and articulate. We received lots of great feedback—in fact, so much that I typed eight pages of notes to capture everything we learned. The bottom line is that neither concept was appealing enough to customers. However, there were a few rays of sunshine that managed to poke through the clouds.

The core part of the value proposition in both concepts—“find out what ‘they’ know about me”—only had limited appeal. Customers found the Marketing Report and Marketing Profile somewhat interesting, but not compelling. Most of them found the Marketing Score confusing and it had low appeal.

The features for comparing oneself to others and social networking in the Saver concept had low appeal with customers. However, customers did like money-saving offers (one of our rays of sunshine). This was the most appealing part of the Saver concept. The idea of reducing junk mail had strong appeal in the Shield concept, as did the idea of saving trees as a secondary benefit. I should clarify that “strong appeal” was still far from a slam-dunk. Customers had plenty of questions and concerns about what we showed them. However, I was confident we could use what we learned to avoid those concerns and make the next revision even stronger. I could tell there was enough latent interest in those benefits.

After the research, I took the map of our problem and solution spaces—originally shown in Figure 11.2—and colored each box green, yellow, or red for strong, some, or low appeal. When I looked at the results, I saw two separate islands of green: the Saver target customers liked money-saving offers and the Shield target customers liked blocking junk mail. The two options for moving forward were clear: we just had to pick which direction we wanted to pivot.

ITERATE AND PIVOT TO IMPROVE PRODUCT-MARKET FIT

While both concepts had strong appeal, the appeal for Shield was stronger. Because a lot of websites already provided money-saving offers (such as coupons.com) for Savers, it wasn't clear to customers how our offering was differentiated. Also, customers were less willing to pay for this service and said that they would only be willing to pay a price that was less than the actual savings it achieved for them. In addition, it would take a lot of effort to sign deals with the companies that would make the offers, and this service wasn't a great fit with the company's brand.

In contrast, we detected a stronger potential product-market fit for Shield. Customers seemed more willing to pay for a service that reduced their junk mail. We had introduced the concept of paying for the service with the “Marketing Shield Premium” upgrade option. Some customers told us that if the service really worked as expected during an initial free trial period, they would be willing to pay afterwards. When asked how much they would be willing to pay for a service like this, some people indicated that it would be a small amount—but we didn't get a strong response. This service was also a better fit with the company's brand.

The Pivot

Based on what we learned, we decided to abandon our previous core value proposition of “finding out what ‘they’ know about me” and pivot to a service that only dealt with blocking junk mail. We tentatively named it JunkmailFreeze. At this point, we identified three options for how to proceed. The first was to create a new set of mockups, test it with customers, and then build the product. The second option was to code a higher fidelity prototype in HTML and CSS to test with customers and then build the product. The third option was to design and build the product without bothering to test with customers again beforehand.

We decided go with the first option. JunkmailFreeze was quite a pivot away from our core concept, and we had learned a lot about how to improve the junk mail blocking service. Plus, it wouldn't take much time to generate a new set of mockups and recruit another batch of customers. We decided to speak with fewer customers this time in the interest of saving some time and money.

Iterating Based on What We Learned

We tossed out our old mockups and started fresh to design a new product focused on reducing junk mail, with a secondary benefit of saving trees. We came up with a pretty straightforward user experience for our new MVP prototype. It started with an email from a friend recommending JunkmailFreeze with a link to the home page that explained the benefits and had a big “get started” conversion button. It also had a “learn more” link. Clicking the “get started” button led to a simple sign-up page where the user entered their name, address, email address, and password. After clicking the “register” button on that page, the user was taken to the “my account” page where they could specify which types of junk mail they no longer wished to receive. The other pages up to that point explained the benefits of using JunkmailFreeze; but this was the key page where the user interacted with the product to achieve those benefits.

Before we had conducted our first round of user testing, our view of the relevant benefit was simply to reduce the amount of junk mail a customer received. We learned so much more about the problem space after talking with users. We learned that there were certain types of junk mail that almost all customers hated the most: preapproved credit card offers and cash advance checks. Most customers do not have a secure (locked) mailbox. So they were worried that someone could steal a preapproved credit card offer from their mailbox and open a credit card in their name, or steal a cash advance check and use it. We used that knowledge to craft relevant messages in our new designs.

In general, finance-related junk mail was the top area of concern—including the types just mentioned, as well as loans and insurance. Customers had concerns about these types of junk mail increasing the risk of identity theft. It seemed that every customer we spoke with knew someone who had been a victim of identify theft. So we added the benefit of reducing the risk of identity theft to our messaging.

We learned that many privacy-conscious customers spend a lot of time shredding their junk mail. Several told us that when they get home from work, they take their mail out of their mailbox and stand next to their paper shredder as they read through it, shredding as they go. This nightly routine takes five minutes for some people, which adds up over time. We realized that there was also a “save time” benefit associated with reducing junk mail and added that to our messaging.

We also learned that customers considered catalogs to be a pain because they are so big and bulky. People discard many unwanted catalogs and consider it a hassle and quite a waste of paper. However, we also learned that people still wanted to receive certain catalogs, and that different people had different preferences for the types of catalogs they wanted to receive.

We also learned that many customers consider local advertising a nuisance. One form was the pack of local coupons, which many people tossed out without opening. Another form was circulars and flyers from local business such as supermarkets. People also complained about being sent free local newspapers to which they hadn't subscribed.

This is a great example of how talking to customers helps you gain such a deeper understanding of the problem space. We learned so much that our new “My Account” page let the user block up to 31 different types of junk mail across seven categories. After users selected which types of junk mail they wanted to block, they clicked the “continue” button to complete their registration.

The “registration complete” page told users what to expect next: that in the next couple of months, they should see a dramatic reduction in the amount of junk mail they receive in the categories that they selected. For our first round of testing, we learned that customers expected that the service would take a while to “kick in.” We also knew that operationally it would take a while for the service to go into effect for each customer.

The page also explained that users could return to JunkmailFreeze at any type to change the types of junk mail they wish to freeze. We had learned from our first round of research that it was important to customers that they be able to change their settings. Several expressed concern that by blocking their junk mail, they may inadvertently not receive some type of mailing that they would want to receive. Because the messaging on this page matched customer expectations, most nodded or said, “That sounds good,” when they read it.

We provided a “learn more” path for customers who weren't ready to sign up right away. We explained on the “learn more” page how JunkmailFreeze contacts direct mailing companies on your behalf to get off their mailing lists. We explained that you would still be able to receive direct mail items that were important to you. Because identity theft was such a large concern related to junk mail, we also provided a page that explained how the two were connected. It included a photo of a row of vulnerable mailboxes and explained how you could reduce your risk of identity theft by using our service.

Because customers had a lot of questions about who was providing this service during the first round of user testing, we also added an “About us” page. They wanted to know about the company and its background.

Wave 2

Now that our JunkmailFreeze mockups were done, we recruited another group of customers using the same Shield screener, since it had worked so well. For this second wave, we scheduled three groups of two customers each. I updated the research script to focus on junk mail. The sessions were 90 minutes long starting at 6 and 8 P.M. (same as last time). Because we had done a fair amount of discovery in the first wave and wanted to focus on getting the product details right in this wave, we spent more time on the mockups (45 minutes instead of 35). I moderated the user testing, and our recruits were again engaged and articulate.

Climbing the Product-Market Fit Mountain

The second wave of user testing was one of the coolest things I've seen—and the results were very different from the first. None of the customers had any major concerns or questions with the product. Instead, there was a lot of head nodding as they went through the mockups, and unsolicited comments like “Oh, this is great.” They did have minor comments, questions, and suggestions. But because we had learned what the major issues were in the first round and had adequately addressed them in our second wave mockups, everyone really liked our product.

That being said, the mockups we showed weren't “done.” We gained an even deeper understanding about what customers wanted in a junk mail blocking service. For example, we learned that category-level controls for blocking weren't adequate for junk mail related to credit cards and catalogs. For those items, customers wanted to the ability to specify their preferences at the individual company level (e.g., Chase or Wells Fargo for credit cards, Nordstrom or L.L. Bean for catalogs). We also received feedback on our messaging and UX that would further improve the product.

This time when we asked customers how much they would be willing to pay for a service like this, we saw a stronger willingness to pay and a willingness to pay a higher amount compared to the first wave. You always have to be a bit skeptical when you discuss pricing with customers. Again, what they say they would do and what they would actually do can be different. You don't really know what they will be willing to pay until you have a real product and they have to vote with their wallet. But there was clearly much stronger interest in our wave 2 product. I felt confident that we had achieved an adequate level of product-market fit with our mockups to move forward.

There was one more reason I felt confident. After each test was over, I thanked the customers and gave them their compensation checks. After receiving his or her check, every customer asked me if this service was live now and if they could sign up for it. When I explained that it hadn't been built yet, they all asked if I would please take their email address and notify them when it was available. None of the customers in the first wave had exhibited any behavior like this. Because this was genuine, positive customer interest outside the scope of our user test, I took it as further proof of product-market fit.

REFLECTIONS

Before this particular project, I had conducted various types of customer research to solicit user feedback on a product or product concept, and I had been on teams that practiced user-centered design. But this project was the first time that I created and tested a product idea in such a Lean way. Focusing on mockups and not coding anything allowed us to iterate rapidly. By being rigorous about our target customer with our screener we were able to recruit customers that gave us great feedback. The whole project took less than two months and used resources very efficiently. I was excited that in so little time—and with just one pivot—our small team was able to improve our product idea so much and achieve a high level of product-market fit.

I also like to share this example with others because we didn't really do anything special or unique. We just followed the Lean Product Process. There's no reason anyone else couldn't replicate the results we achieved. By following the process I describe in this book, any team should be able to achieve similar results with their product idea. Of course, the details of how it works out in your case will vary. It may take you more waves. You may not have to pivot, or you may have to pivot more than once. And there's no guarantee you will achieve product-market fit for every product idea you pursue. But you should be able to test your hypotheses and assess your level of product-market fit with confidence.

As previously discussed, you can conduct user testing with design artifacts or a live, working product. To minimize risk, make faster progress, and avoid waste, I strongly recommend getting feedback on design artifacts before you start coding. This will allow you to be more confident in your hypotheses before you invest in coding. Once you have validated your mockups or wireframes with customers, it is time to start building your product. All the learning you gain in the Lean Product Process will help you better define the product to build. In the next chapter, I offer advice on how to go about building your product.