Chapter Thirteen

Profit from the Majesty of Simplicity and Parsimony

Hold Traditional Low-Cost Index Funds That Track the Stock Market.

WHAT LESSONS HAVE WE learned in the previous chapters?

- Costs matter (Chapters 5, 6, and 7).

- Selecting equity funds based on their long-term past performance doesn’t work (Chapter 10).

- Fund returns revert to the mean (RTM) (Chapter 11).

- Relying even on the best-intentioned advice works only sporadically (Chapter 12).

If low costs are good (and I don’t think a single analyst, academic, or industry expert would disagree with the idea that low costs are good), why wouldn’t it be logical to focus on the lowest-cost funds of all—traditional index funds (TIFs) that own the entire stock market? Some of the largest TIFs carry annual expense ratios as low as 0.04 percent, and incur turnover costs that approach zero. Their all-in costs, then, can come to just four basis points per year, 96 percent below even the 91 basis points for the lowest-cost quartile of funds described in Chapter 5.

And it works. Witness the real-world superiority of the S&P 500 Index fund compared with the average equity fund over the past 25 years and over the previous decade, as described in earlier chapters. The case for the success of indexing in the past is compelling and unarguable. And with the outlook for subdued returns on stocks during the decade ahead, let’s conclude our anecdotal stroll through the relentless rules of humble arithmetic with a final statistical example that suggests what the future may hold.

The Monte Carlo simulation.

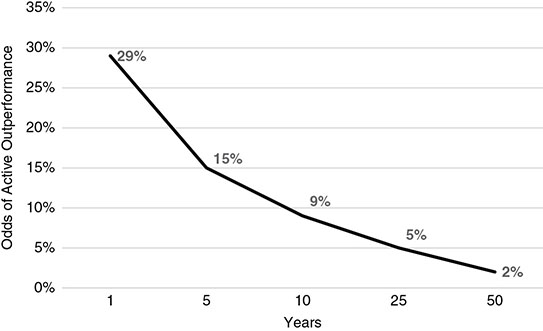

We can, in fact, use statistics designed to project the odds that a passively managed index fund will outpace an actively managed equity fund over various time periods. The complex exercise is called a “Monte Carlo simulation.”1 What it does is make a few simple assumptions about the volatility of equity fund returns and the extent to which they vary from the returns earned in the stock market, as well as an assumption about the all-in costs of equity investing. The particular example presented here assumes that index fund costs will run to 0.25 percent per year and that the all-in costs of active management will run to 2 percent per year. (Index funds are available at far lower costs, and many equity funds carry even higher costs. So we’ve given actively managed funds the benefit of a very large doubt.)

Result: Over one year, about 29 percent of active managers, on average, would be expected to outpace the index, and over five years about 15 percent would. After 50, years only 2 percent of active managers would be expected to win (Exhibit 13.1).

The majesty of simplicity in an empire of parsimony.

EXHIBIT 13.1 Odds of an Actively Managed Portfolio Outperforming Passive Index Fund

How will the future actually play out? Of course, we can’t be sure. But we know what the past 25 years looked like, and we saw in Chapter 10 that since 1970 only two of the 355 funds in business at the outset outperformed the stock market index by 2 percent or more per year. What’s more, one of these winners lost its early edge two full decades ago. So it looks as if our statistical odds are in the right ballpark. This arithmetic suggests—even demands—that index funds deserve an important place in your portfolio, even as they constitute the overriding portion of my own portfolio.

In the era of subdued stock and bond market returns that most likely lies in prospect, fund costs will become more important than ever—even more so when we move from the illusion that mutual funds as a group can capture whatever returns our financial markets provide to the even greater illusion that most mutual fund investors can capture even those depleted returns in their own fund portfolios. What the index fund has going for it is, as I have often said, “the majesty of simplicity in an empire of parsimony.”

To reiterate: all those pesky costs—fund expense ratios, sales charges, turnover costs, tax costs, and the most subtle cost of all, the rising cost of living (inflation)—are virtually guaranteed to erode the real spending power of our investments over time. What’s more, only in the rarest cases do fund investors actually succeed in capturing the returns that the funds report.

My conclusions rely on mathematical facts—the relentless rules of humble arithmetic.

My conclusions about the market returns that we can expect in the years ahead may be wrong—too high or too low. But my conclusions about the share of those returns that funds will capture, and the share of those returns that we investors will actually enjoy, have one thing in common: They rely, not on opinion, but largely on mathematical facts—the relentless rules of humble arithmetic—that make selecting winning funds akin to looking for a needle in a haystack. Ignore these rules at your peril.

If the road to investment success is filled with dangerous turns and giant potholes, never forget that simple arithmetic can enable you to moderate those turns and avoid those potholes. So do your best to diversify to the nth degree, minimize your investment expenses, and focus your emotions where they cannot wreak the kind of havoc that most other investors experience. Rely on your own common sense. Emphasize an S&P 500 Index fund or an all-stock-market index fund. (They’re pretty much the same.) Carefully consider your risk tolerance and the portion of your investments you allocate to equities. Then, stay the course.

All index funds are not created equal. Costs to investors vary widely.

I should add, importantly, that all index funds are not created equal. Although their index-based portfolios are substantially identical, their costs are anything but identical. Some have minuscule expense ratios; others have expense ratios that surpass the bounds of reason. Some are no-load funds, but nearly a third, as it turns out, have substantial front-end loads, often with an option to pay those loads over a period of (usually) five years; others entail the payment of a standard brokerage commission.

The gap between the expense ratios charged by the low-cost funds and the high-cost funds offered by 10 major fund organizations for their S&P 500 Index–based funds runs upward of an amazing 1.3 percent of assets per year (Exhibit 13.2). Worse, the high-cost index funds also saddle investors with front-end sales loads.

EXHIBIT 13.2 Costs of Selected S&P 500 Index Funds

| Five Low-Cost 500 Index Funds | Annual Expense Ratio | Sales Load |

| Vanguard 500 Index Admiral | 0.04% | 0.0% |

| Fidelity 500 Index Premium | 0.045 | 0.0 |

| Schwab S&P 500 Index | 0.09 | 0.0 |

| Northern Stock Index | 0.10 | 0.0 |

| T. Rowe Price Equity Index 500 | 0.25 | 0.0 |

| Five High-Cost Funds | ||

| Invesco S&P 500 Index | 0.59% | 1.10% |

| State Farm S&P 500 Index | 0.66 | 1.00 |

| Wells Fargo Index | 0.45 | 1.15 |

| State Street Equity 500 Index | 0.51 | 1.05 |

| JPMorgan Equity Index | 0.45 | 4.80 |

Even among the low-cost S&P 500 Index funds, we see a wide range of expenses. While the Admiral class of Vanguard’s index fund carries a minuscule 0.04 percent expense ratio, the T. Rowe Price fund charges 0.25 percent. Although lower than the high-cost index funds, that T. Rowe Price fund is hardly “low.” Assuming an annual return of 6 percent compounded over 25 years, an initial investment of $10,000 would grow to $40,458 in the T. Rowe Price index fund. With a truly low-cost index fund carrying an expense ratio of 0.04 percent, that $10,000 investment would grow to $42,516, an increase of $2,058 over the higher-cost index fund. Yes, even seemingly small differences in costs matter.

Today, there are some 40 traditional index mutual funds designed to track the S&P 500 Index, 14 of which carry front-end loads ranging between 1.5 percent and 5.75 percent. The wise investor will select only those index funds that are available without sales loads, and those operating with the lowest costs. These costs—no surprise here!— directly relate to the net returns delivered to the shareholders of these funds.

Two funds. One index. Different costs.

The first index fund was created by Vanguard in 1975. It took nine years before the second index fund appeared—Wells Fargo Equity Index Fund, formed in January 1984. Its subsequent return can be compared with that of the original Vanguard 500 Index Fund since then.

Both funds selected the S&P 500 Index as their benchmark. The sales commission on the Vanguard Index 500 Fund was eliminated within months of its initial offering, and it now operates with an expense ratio of 0.04 percent (4 basis points) for investors who have $10,000 or more invested in the fund.

In contrast, the Wells Fargo fund carried an initial sales charge of 5.5 percent, and its expense ratio averaged 0.80 percent per year (the current expense ratio is 0.45 percent). Behind the eight-ball at the start, the fund falls further behind with each passing year.

Your index fund should not be your manager’s cash cow. It should be your own cash cow.

During the 33 years since 1984, these seemingly small differences added up to a 27 percent enhancement in value for the Vanguard fund. An original investment of $10,000 grew to $294,900 in the Vanguard 500 Index Fund as 2017 began, compared with $232,100 for the Wells Fargo Equity Index Fund. All index funds are not created equal. Intelligent investors will select the lowest-cost index funds that are available from reputable fund organizations.

Some years ago, a Wells Fargo representative was asked how the firm could justify such high charges. The answer: “You don’t understand. It’s our cash cow.” (That is, it regularly generates lots of profits for the manager.) By carefully selecting the lowest-cost index funds for your portfolio, you can be sure that the fund is not the manager’s cash cow, but your own.

Whether markets are efficient or not, indexing works.

Conventional wisdom holds that indexing may make sense in highly efficient corners of the market, such as the S&P 500 for large-cap U.S. stocks, but that active management may have an advantage in other corners of the market, like small-cap stocks or non-U.S. markets. That allegation turns out to be false.

As shown in Exhibit 3.3 in Chapter 3, indexing works perfectly well wherever it has been implemented. As it must. For, whether markets are efficient or inefficient, all investors as a group in that segment earn the return of that segment. In inefficient markets, the most successful managers may achieve unusually large returns—but that means some other manager suffered unusually large losses. Never forget that, as a group, all investors in any discrete segment of the stock market must be, and are, average.

International funds also trail their benchmark indexes.

International funds are also subject to the same allegation that it is easier for managers to win in (supposedly) less efficient markets. But to no avail. S&P reports that its international index (world markets, less U.S. stocks) outpaced 89 percent of actively managed international equity funds over the past 15 years.

Similarly, the S&P emerging markets index outpaced 90 percent of emerging market funds. With indexing so successful in both more efficient and less efficient markets alike, and in U.S. markets and global markets, I’m not sure what additional data would be required to close the case in favor of index funds of all types.

Caution about gambling.

Caution: While investing in particular market sectors is done most efficiently through index funds, betting on one winning sector and then another is exactly that: betting. But betting is a loser’s game.

Why? Largely because emotions are almost certain to have a powerful negative impact on the returns that investors achieve. Whatever returns each sector may earn, the returns of investors in those very sectors will likely, if not certainly, fall well behind them. There is abundant evidence that the most popular sector funds of the day are those that have recently enjoyed the most spectacular recent performance. As a result, a strategy of trading based on after-the-fact popularity is a recipe for unsuccessful investing.

When trying to pick which market sector to bet on, look before you leap. It may not be as exciting as gambling, but owning the traditional stock market index fund at rock-bottom cost is the ultimate strategy. It holds the mathematical certainty that marks it as the gold standard in investing. Try as they might, the alchemists of active management cannot turn their own lead, copper, or iron into gold. Avoid complexity and rely on simplicity and parsimony, and your investments should flourish.