The Barroom: The Bar Is Open

So...Time for those blessed words that are uttered at the end of many a tough day in the field...

Let’s call it Louie’s East, in honor of that semi-famous dive that used to be on the corner of 41st and 2nd Avenue and served as the unofficial watering hole, hideaway, strike war room, and confessional of the New York Daily News. Often, as a copyboy, I would be dispatched to the third floor, where in the din of presses that at the time jack hammered out over a million papers a night, I would pick up a few dozen one-stars, the Bulldog, the first edition of tomorrow’s paper.

Next stop, Louie’s East. I would not return to the seventh floor newsroom. I would go downstairs, cross the street, and walk through the doors and into a solid wall of stale beer smell. I would then walk along the bar and distribute papers, and editors would phone in their corrections over a boilermaker or two.

I’m not disparaging the place unfairly. It actually reveled in how scruffy it was. There was graffiti in the men’s toilet that read, “Don’t do no good to stand on the seat...the crabs in here jump 10 feet.” I shit you not, to continue the visual.

It was part of the mix, the culture of New York journalism. Here would mix poets and scribes and columnists and editors and photographers, all reveling together in the imperfect and wonderful occupation of telling stories. It was here I think I first heard that old wink-wink tabloid mantra: “Some facts are too good to check....”

Tales got told. Here are a few...

Bad Days Can Make for Great Pictures

“I had one clean, dry 50mm lens in my pocket. I rewired that camera, popped the lens on, and patted it for luck.”

A bad day in the field beats a good day at the office, anytime. There are days that test this proposition. I once destroyed five motor-driven Nikons in one day. That was a bad day in the field.

When shooting a space shuttle launch, you are relying mostly on cameras you can’t be with or near. They’re called remotes, and you put them in the field 24 hours in advance of liftoff, rigged with devices that will trigger them (hopefully) at the right time. At launch time, you’re miles away, shooting a 1000mm lens through the heat waves. Lots of luck with that.

I put nine cameras in the field—the field being the saltwater estuary surrounding the launching pads at Cape Kennedy. I had high hopes.

A storm hit before liftoff. One of the worst I’d ever seen. All the photographers begged NASA to go back out and see what was left of their stuff. It was a camera graveyard out there. Grown men were crying. In my case, the only evidence of one of my rigs was three inches of tripod leg sticking out of the flooded swamp. I waded in up to my neck, eyeballing alligator warning signs, trying to haul my gear up from the muck.

Seeing as I was already in the swamp, I tried to get out some of the other shooters’ gear as well. They were standing on the bank, giving me directions. Since they were from the South, I asked if any of them knew whether a big storm got the gators riled up and made them more active. An answer came back: “Don’t you worry. Y’all just go get our stuff.” Probably the best use they’d ever seen for a Yankee.

My last rig was damaged, but not destroyed. I had one clean, dry 50mm lens in my pocket. I rewired that camera, popped the lens on, and patted it for luck. It was still pouring, and I figured I was just SOL. Turns out, the camera fired. Got a picture that ran as the cover of the year in a science issue for Discover, and it saved my butt.

The hard part was still to come. I had to call Al Schneider, cigar-chomping manager of the Time Life photo equipment area, to tell him I just destroyed a good chunk of the company’s pool photo gear. The cameras were in a garbage can in my shower at the Days Inn, being flushed with fresh water, when I called. Al chuckled. “I got the perfect solution for ya, kid,” he said. My heart skipped a hopeful beat. “Yeah,” he went on. “Deeper water.”

It’s a Rocky Road to Freelanceville

“Gosh, you mean after I get approved by a bunch of 20-year-olds, and I shoot it for free, I might get to use it after six months? Where do I sign up?”

My studio manager got this not too long ago from a magazine:

“Thanks very much for your email. It looks like before confirming this, both of our ends have to check on remaining details, i.e., our whole creative team has to agree on contracting Joe. Additionally, while we are happy to take care of the production legwork—i.e., getting the talent, clothes, makeup and styling, location scouted, and permission acquired—we generally do not offer a fee for photography. Unfortunately, with the increase of our circulation came staggering print cost increases. It is a large shot (virtually a full page), however, and a dynamic image. I will also get back to you ASAP with regard to usage, but I imagine that he will be able to publish it wherever he likes after 6 mos. time.”

Gosh, you mean after I get approved by a bunch of 20-year-olds, and I shoot it for free, I might get to use it after six months?

Where do I sign up?

One of the new road signs to Freelanceville.

Photo © Brad Moore

Be a Pest

I was shooting a Time cover on the launch of Disney’s Animal Kingdom. Disney being Disney, they jumped into the zoo business with both feet, scouring zoos everywhere and buying up bunches of animals.

It was a cover story, so there was a lot of pressure. I needed certain things to happen which weren’t happening.

The main attraction was the safari ride, which I was told I had to shoot from the safari vehicles on the established path of the ride. No exceptions. I told them this was impossible. How do you shoot a picture of something you’re sitting on?

I also wanted to shoot behind the scenes with the animals, to show how they were being cared for. Disney didn’t want to show the animals behind bars. They wanted the public to believe that at night, the animals were being cared for by Mickey and Tinker Bell, and instead of being caged, they were chatting amongst themselves and hanging around at Pleasure Island.

They told me behind-the-scenes photos were impossible.

I knew I had to go to the top. Michael Eisner and I go way back. I’ve put him in a tree. I’ve shot him with Roger Rabbit. We’ve also done some male bonding in an 80-foot bucket crane over Disney-MGM Studios. He’s actually okay to photograph and knows the value of a picture.

Time’s writer was interviewing Eisner over lunch at Animal Kingdom. Being the photographer on the story, I knew I wasn’t invited. The only way I’d get close to the table was to put on a waiter’s uniform. I hung out at the bar, biding my time. The writer had promised me he’d take my case to Eisner. Right.

The lunch broke. I made my move, cutting Eisner off in between the tables, giving him nowhere to go.

He rolled his eyes. “What do you want?” was the first thing out of his mouth. “I need to get off the safari path, and I need to get behind the scenes with the animals.” You have to hit it hard and fast. He also knew I was a persistent pain in the a$$, which worked in my favor.

“Okay for the safari and behind the scenes if it’s just for Time.” He looked around and his people all nodded. Done.

Both pictures ran. Photographers... we’re pests. But we know what we know.

“Be a PEST! They told me behind-the-scenes photos were impossible.”

Never Live with a Model

Never live with a fashion model.

I did. What can I say? The guys at the Daily News loved her, and were always asking for updates about my love life. Particularly Caruso, who was one of those Italian guys from Brooklyn who just adored women.

But we broke up. Badly. Had to throw her out. In December. I moped into the News. Caruso saw me. “Hey howzitgoin’? How’s the girlfriend?” I shook my head. “Not too good,” I said. “I hadda throw her out. She’s gone.”

His eyes widened. He grabbed me and threw me back against the wall. He had a wild look on his face. “You trew her out?!” he screamed in his best Brooklynese. “In the deada winta? Right before da holidays? You heartless bastard!”

Then he beamed and clapped me on the shoulder. “You could be management!”

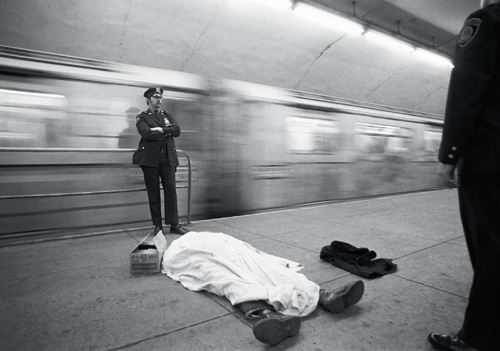

Dead Guys

“I was always very careful when processing his film, ’cause the outline of a huge handgun was always plainly visible under his sweater.”

Back in the ‘70s in New York, dead people turned up regularly. Subway platforms, street corners, parks—you name it. You just stepped over them on the way to work.

Naturally, the Daily News had a crime photog who worked the overnight shift. Big guy, made bigger by the cowboy hat he often wore and the bulky sweaters he usually had on, even in the summer.

I was always very careful when processing his film, ‘cause the outline of a huge handgun was always plainly visible under his sweater.

Not that it was ever complicated. He shot 20-exposure rolls of Tri-X[1], and there were usually three frames: one out-of-focus frame of the trunk of his car (as he retrieved his gear and loaded his film), another out-of-focus frame of his feet as he walked over to the scene of the crime, and a reasonably sharp shot of the dead body.

[1] Tri-X—Kodak Tri-X is the legendary black-and-white film for the ages, staple for many years of photojournalists everywhere.

That was it. Short and sweet. I always told him I liked his work.

Just Go Make a Picture

“Maybe if you had a nanny kissing a moose. I’m just thinking out loud, Joe.”

How about kissing a moose? Well, maybe just kiss the baby.

It was my second story for Life. I was excited, but still terrified I would screw up and spend the rest of my career shooting for Compressed Air Monthly.

The story was on nannies, a newsworthy item back in those days. John Loengard, picture editor and provocateur, called me in to discuss ideas. To John, a nanny was Mary Poppins, complete with pram and starchy uniform. I was shooting the story out west and the visual changeup had John’s juices flowing.

“How about all the proper nannies and their babies out in the Rocky Mountains?” he suggested. “Or maybe one (in uniform) with her pram walking through a dusty cowboy town?” None of that was going to happen, but that didn’t matter to John.

He paused. “Maybe if you had a nanny kissing a moose. I’m just thinking out loud, Joe.”

I, of course, nodded and staggered out of his office. Mel Scott, the deputy picture editor, saw me with my eyeballs rolling around. He knew what’d happened.

He motioned to come into his office and closed the door. “Okay Joe, what you gotta do now is put all that stuff out of your head and just go make a picture. Ya hear me?” He had this great Texas accent. “Just go make a picture.”

John and Mel were the best good cop/bad cop act in all of photography. John would get you to think (and occasionally scare the bejeezus out of you), and Mel would calm you down and tell you everything was gonna be all right.

As photographers, as an industry, we sorely miss both of them.

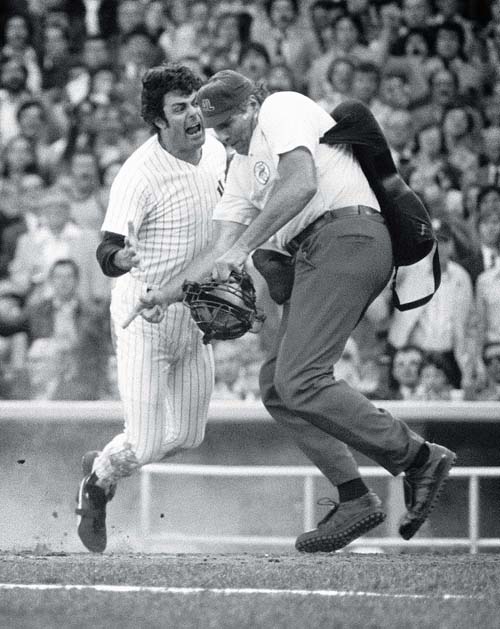

It Only Takes One...

“Feeling pretty good, huh, kid? That’s an attaboy, a good job... just remember,” he said, “It only takes one ‘aw, shit’ to wipe out three ‘attaboys’.”

It was a picture of a famously huge argument and I got it because I lied. A real New York story.

The person I lied to was Larry DeSantis, the legendary UPI pictures editor, a giant, bespectacled bear of a man who was anything but cuddly. You loved him, you hated him, and at all times, you feared him.

I came to Larry’s attention in 1978, while I was participating in what was at that time a rite of passage in the New York newspaper industry, a strike. While the pen may be mightier than the sword, in the New York press game, the truck is mightier than the sword, the pen, and the camera put together. The pressmen had gone on strike, the drivers sided with them, and that was that. Management could write the paper, shoot the paper, and even print the paper, but what was the point if you couldn’t deliver it?

The Daily News shut down for 88 days and, though I was still just a copy boy, I started shooting pictures for UPI. I was right up their alley in terms of employment: a warm body with a camera who was willing to work cheap. One day in the office, Larry looked at me and croaked, “You ever shoot baseball?” Enter the lie. “Oh, yeah,” I gushed. “Syracuse (my college town) had a semi-pro team. I shot baseball all the time.” As was his way, Larry grabbed me by my belt and pulled me toward his desk. Still holding my belt, Larry took a Yankees credential and stuffed it into my crotch. “Third base,” was all he said.

I floated down the hallways toward the elevators. I was just a copy boy at the News, and here I had the UPI third base credential for the Yankees-KC playoffs in my underwear! Then it hit me. I had never shot a baseball game before in my life.

As a photographer, when asked such questions by an editor, you should always say yes, even if the assignment terrifies you. (Actually, especially if it terrifies you.) That is not to say such adventurism doesn’t produce qualms and difficulties. In those days of wet darkrooms, when some technician was working like a stevedore in a closet-sized room in the bowels of an athletic stadium, and the film was getting ripped out of the hypo, sloshed in some water, louped, and printed while still wet, you obviously didn’t overshoot and send roll upon roll back to the beleaguered processing operation. During a big playoff game, you’d shoot everything, but you didn’t ship everything.

I was so terrified in my first games that I shot like mad, and shipped like mad. At the end of one dismal effort on my part, Larry motioned me over, in disgust. If you’d put a nun’s habit on him, I would’ve felt like I was in third grade again.

“Tonight,” he said, “You set the world’s record for shipping me INSIGNIFICANT film. Ground balls. Pop ups. What’s this garbage? @!!%$#$!”

He concluded with a brief analysis of my ancestry and a quick overview of his rather dim hopes for my future in the business.

This was all done quite publicly. I felt like my pants had been taken down in front of the entire N.Y. press corps, many of whom were enjoying the rookie’s embarrassment.

The next night, I got this picture, which became one of the most widely published of the playoffs. I watched it spin on the wire machine after the game, feeling redemption with every beep of the transmission. Larry walked up to me. “Feeling pretty good, huh, kid?” he asked. Nodding with affirmation, he continued, “That’s an attaboy, a good job.” An enormous forefinger waved slowly in front of my face. “Just remember,” he said, “It only takes one ‘aw, shit’ to wipe out three ‘attaboys.’”

Career advice for the freelancer.

Lou Piniella & Ron Luciano

Think Romance!

“Then I start thinking...Beauty and the Beast! They’re, you know, like, in LOVE! My mind starts racing. They’re gonna go upstairs and do it!”

It helps to be a bit of a romantic sometimes. I was shooting the A Day in the Life of Hollywood book and one of my stops was to make pictures of Alan Menken getting a BMI music award for Beauty and the Beast at the Regent Beverly Wilshire Hotel.

For a photographer, an award ceremony is a non-starter. Uhh, lessee...should I cover the award ceremony, or should I go get that long overdue root canal? Hmmm....

Anyway, Menken wins the award, and the photogs close in and go disco, shooting flash so motor-driven fast they must have had Honda generators strapped to their belts. I’m in the mix, doing the same thing, thinking, man, the movie might be a hit, but this picture I’m getting closes out of town.

The furor calms down, and Beauty and the Beast walk away. I walk away, too, but then I start thinking...Beauty and the Beast! They’re, you know, like, in love! My mind starts racing. They’re gonna go upstairs and do it! The Beast must have an enormous schvenstalker! They’re heading for the elevators!

Luckily, the Bev Wilshire hotel has a sweeping staircase with two sets of steps. Beauty and the Beast lumber up one, and I sprint up the other. They get to the elevator bank and...there’s Joe!

I got a frame that was a double truck[1] in the book.

[1] Double Truck: A double truck is a two-page spread.

Eddie Being Eddie

First time I ever saw Eddie being Eddie was at the 1980 Democratic National Convention. Eddie is Eddie Adams, of course—shooter, legend, raconteur, hero, rock star, sage, keeper of the “Shit List,” friend, mentor, and (occasionally) irascible old coot.

I didn’t know him back then. I was a newbie, and he was Eddie. He seemed pretty gruff. I was scared of him.

But I did notice him going around with this galoot of an assistant who obviously didn’t know anything about photography. Curious. The guy was big enough to play linebacker for the Chicago Bears, and in fact, probably did, but a photog he wasn’t. But the guy was big. Real big.

So the last night of the convention, President Carter, ever the populist, decides to walk through the convention floor to the podium instead of using the back hallways like the elitist sumbitches most politicians are, and it drove the Secret Service nuts. Tension was high. People were jammin’, trying to get a piece of the man from Plains, and security was determined not to let that happen.

What did happen was about a 100-yard free-for-all scrum across the length of the convention floor. Cops and G-men formed a flying wedge and drove forward, trampling all in their path. Conventioneers pushed back and mayhem ensued. I tried to get a picture by standing on a collapsible chair. Bad move. I went down, hard. Got nothing.

My one memory as I fell was Eddie Adams wading through the crowd like Moses with a Leica, astride the shoulders of his linebacker assistant, who was making short work of the respectable delegates from the great states of Alabama, Connecticut, and Rhode Island by simply picking them up and tossing them aside.

I was lying on the floor with the skid marks of peoples’ shoes all over me and my gear and thought, “Son of a b!&¢# knows what he’s doin!”

“My one memory as I fell was Eddie Adams wading through the crowd like Moses with a Leica, astride the shoulders of his linebacker assistant....”

President Carter

Not Everyone’s Gonna Love You

“Not everybody’s gonna think your stuff is the greatest thing since sliced bread. Put a picture out there, and anybody who sees it can say anything they want about it. It isn’t the business for a thin skin.”

At the Daily News, we used to edit by projecting the negs on screens. It was a brilliant way to edit B&W, ‘cause reading the neg instead of the contact sheet would give far better info about sharpness and quality. Editors like Phil “Stanzi” Stanziola were terrific at essentially reading in reverse...the negative instead of the positive.

When your stuff was on the screen, of course, the standard comment from passers-by would always be something like, “Whose $#!% is this?” It would go downhill from there, especially if something was, you know, soft. (I’ll leave that range of commentary to your imagination.)

Some folks are gonna love your stuff and some are gonna hate it. Some editors will adore you as a shooter, and others wouldn’t assign you to an “Editor’s Note” job.

I’ve always taken solace in the philosophy of good ol’ Miss Lillian, Jimmy Carter’s mom. Campaigning for her son, she was brought up short by an earnest young gentleman who shared that he liked her a lot, but he wasn’t going to vote for her son.

She just laughed and patted him on the cheek. “That’s okay son, we didn’t expect it to be unanimous.”

Miss Lillian Carter

A Little Terror Can Be Quite Helpful

Never underestimate terror as a motivational tool.

National Geographic sent me to Hawaii to come up with an unusual picture of the Ironman Triathlon.

I was psyched. An underwater view of the Ironman! I did the whole thing—Zodiac boat, underwater camera rigs, permissions, you name it. I was ready.

Morning of the race. I’m in position (40 feet below the surface) waiting for the start. A few swimmers go overhead. Then a couple. Then nobody.

Ever get that sick feeling in your gut, the one that lets you know you really screwed the pooch? I had drifted on my dive. The swimmers went wide of me.

I surface and throw myself into the Zodiac boat and race to the first turn hoping the swimmers would gang up again. I’m trying to reload my cameras and regrease the O-rings as I’m being tossed around in the boat, slammin’ through the waves. No luck at the turn. So we haul a$$ to get to the finish before them. I throw myself into the water again.

It gets worse. As soon as I hit the water, one of my strobes goes disco, a sure sign of a flooded rig. I drop it on the bottom. I see the swimmers starting to funnel down into the finish and I get a camera ready.

And then my regulator starts getting pulled out of my mouth. I look up, and my air tank had slipped its cinch (my bad) and was wanting to scream to the surface, my air supply with it.

I reach up, grab the tank, and tuck it under my left arm. With my right hand, I got a camera to my mask, and squeezed two frames of the bunched swimmers. They never grouped up again like this. I was done for the day.

I mean, how was I gonna call my editor and explain that I just freakin’ missed 2,500 relatively slow-moving people?

“Never underestimate terror as a motivational tool. I mean, how was I gonna call my editor and explain that I just freakin’ missed 2,500 relatively slow-moving people?”

It’s Hard to Strike a Balance

“She reached over with her little hand and patted me on the shoulder and said, ‘Don’t worry, Daddy, just do the best you can.’”

Occasionally I am asked about how to balance the life of a photog with, well, life. In response, I have described my three roles of husband, father, and photographer as three people drowning at once. There is a lot of grabbing, splashing, and flailing about, no one is on the surface for very long, and generally none of the three of us are doing particularly well.

Sometimes you try to be a good dad and it means you’re a bad photographer—you go into the field with no sleep, no prep, and without an idea in your head. The converse is often true. Prepare, get obsessive, dwell on the job, go out there and knock it back and bask in the reverb of a good frame, dream about the phone ringing from JLo’s agent for the cover of her next CD, and...what were my kids’ names again?

I used to even screw up bedtime stories, I was so exhausted most of the time. Caitlin (my 22-year-old daughter) regularly busts me about this now. She even remembers the night I returned from a job in Chicago and tried to tell her the story of the three little pigs. Somehow, what came out of my mouth was, “And all the ships were made of bricks, and it was a good night to Chicago.” No joke. That twist on the old fable stuck in her head, and she trots it out now and then to embarrass me.

We were snuggled one night, and I looked at her and said, “You know, sweetie, daddy’s so tired tonight, I don’t think I can even get through one story.” She was about two. She reached over with her little hand and patted me on the shoulder and said, “Don’t worry, daddy, just do the best you can.”

Claire and Caity

Ask the Tough Question

“Always ask the tough question. It’s a long plane flight home if you don’t. And the more sensitive the question, the more it needs to be asked, and very directly. I’m not saying to be harsh, just direct.”

One of the privileges of my career has been to meet Kim Phuc, a.k.a. The Napalm Girl. Horribly burned at the age of nine in Vietnam, she crusades now for peace.

I was sent to find people who had been the subject of Pulitzer Prize–winning photos. When you’re the subject of a Pulitzer, it is generally not by choice, because by and large, they’re not happy moments.

So it was with Kim. She’s alive because AP shooter Nick Ut took the picture. Then he dropped his cameras and got her to a hospital. But because of the photo, her life became a bizarre, propaganda-driven odyssey. If I ever think pictures aren’t important, and I get tired, frustrated, and down, I think about Kim. Her whole life has spun on a photograph, a slice of a second.

Returning from a Moscow honeymoon, she and her husband applied for asylum in Canada, so I went to meet her in Toronto. We talked. I told her I needed to see her scars. Otherwise, there was no point to my being there. She understood.

Luckily, she was breast-feeding Thomas, her new baby, which gave us the perfect way to show how this beautiful dumpling of a baby sprang from her scarred and battered body. It is a hopeful picture, appropriate for Kim.

Kim Phuc

The Pucker Factor

You always know when you’ve got the frame. I mean the one you come for. Sometimes something we thought sucked actually works out, and sometimes the client hates what we thought was pretty good. But now I’m talking about those frames—the ones that stick. They only come along every once in a while, but when you get one, you know it.

You may know it by a skip of your heart, a short gasp, a split-second of vertigo in your brain, or a feeling like you’ve just gotten a quick punch to the gut.

Or, you may feel it elsewhere. One of the old-timers at the Daily News once looked at me and made a little circle with the tips of his fingers and his thumb, which he then started squeezing and releasing in rhythmic fashion. “You always know when you’re gettin’ good stuff, kid, ’cause you can feel your @$$hole goin’ like dis.” He continued squeezing until he was sure I got the point.

I once related this story to a class of military photojournalists, who immediately classified this as “the pucker factor.”

“You always know when you’ve got THE frame. You may know it by a skip of your heart, a short gasp, a split-second of vertigo in your brain, or a feeling like you’ve just gotten a quick punch to the gut.”

In Space, No One Can Hear You Puke

“With the windowless plane dipsy-doodling, and people standing on the ceiling, and me looking through a lens, I realized why the plane’s nickname was the ‘vomit comet.’”

Bring money! When it comes to getting something done in the field, pronto, there is nothing like cold, hard cash. This is very true in Russia. It’s painfully true when it comes to the Russian space program. U.S. greenbacks are the fuel in the boosters.

I went to shoot a story for Life in Star City, the cosmonaut training center. We had a deal with the Russians. They reneged. Greetings, comrade! We have lied to you repeatedly!

I got onto this plane and got this frame by stuffing $7,500 into the hands of my Russian contact at Star City on a runway in an ice storm. He jammed the wad in his pocket, turned to the pilots, and gave the signal. They spun the props and rolled down the runway.

The zero-G plane flies parabolas—a series of steep dives followed by rapid ascents. At the top of the curve, just before the plane dives again, you go weightless for about 30 seconds. As one American astronaut told me, it’s the most fun you can have with your clothes on. Maybe so. But with the windowless plane dipsy-doodling, and people standing on the ceiling, and me looking through a lens, I realized why the plane’s nickname was the “vomit comet.”

I retched at least 50 or more times. After a while I forgot about the bag and just horked up what was left of my stomach inside my flight suit. I was a sweaty, stinking mess. The Russian doc got so worried he started massaging my ears during the dives so I wouldn’t pass out.

Astronaut Mike Lopez-Allegria held my feet to stabilize me while he was anchored to the floor with a bungee cord. I floated up and made fill flash pictures on Kodachrome. I just kept cleaning out the eyepiece to my camera and hammering frames.

When we landed, I was standing with a bunch of astronauts on the ground, and my stomach dry heaved again. Heard chuckles all around. “Somebody wanna tell Joe here the flight’s over?”

Choosing Is Never Easy

“I wept for her, for me, but mostly because the siren call of my first big story with a yellow border around it was more powerful than the call of fatherhood.”

There needs to be a course in school about how to be a parent and a photographer. Not that we’d listen. All of that is so far away.

I missed a whole bunch of my kids’ growing up. Every traveling shooter does. I have a memory of a day when I was leaving for a four-week trip to Africa for National Geographic. My daughter Caitlin and I were in the driveway. It was hot and the sun was harsh. She was about three years old and had watched the familiar ritual of Dad loading the taxi to go to the airport many times.

I hugged her hard. Told her the usual things. She didn’t understand or care about what I was saying. I knew that. The things we say in these moments to our kids make us feel better, not them.

The cab pulled out and I twisted around and looked back, desperately waving. She couldn’t see me. The light was too bright. She waved once, and left her arm pressed against her forehead, shielding her eyes. The sun was glaring through the dirty window, and she faded from view, hot and yellowish, like an old Polaroid from the ‘50s.

I slid down in the seat and began to weep. I wept for her, for me, but mostly because the siren call of my first big story with a yellow border around it was more powerful than the call of fatherhood.

It’s All About Your Attitude

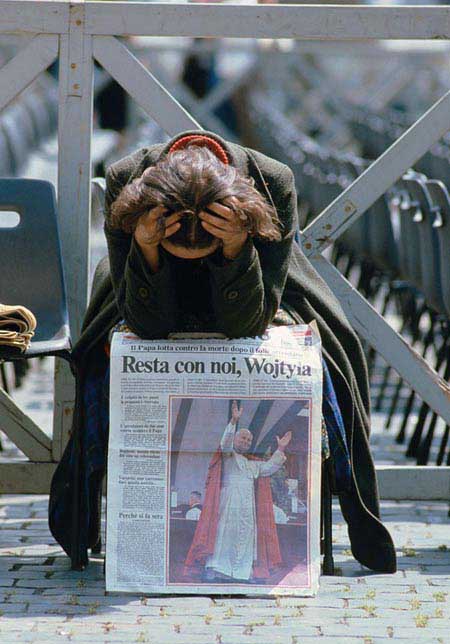

“The man was working at a feverish pitch. This was his pope, his moment, his country. He was making pictures he would tell his grandchildren about.”

The first papal trip to Poland was tough. The government was still Communist, Solidarity was getting feisty, and John Paul’s visit was fuel for that fire. The government put the squeeze on the press, hard.

They would, for instance, make it almost impossible to cover the pope, dropping us miles from the site of the mass, and erecting photo platforms so far from the altar you thought you were shooting a shuttle launch.

This went on for two weeks, a constant battering. I was at one mass in the countryside, and I had all the glass in my bag stacked on my camera, which meant a 400mm lens with a TC 1.4 converter with a doubler on top of that, and through all that the pope was still the size of a pea. To make matters worse, I was shooting in a driving rainstorm.

To add insult to injury, I was shooting for Newsweek, which meant I wasn’t connected. Time had the inside track, because Time had a contract photographer based in Rome. His main strengths were not photographic. He knew how to work the Vatican. He had the place wired.

I’m out there with no picture to make, so just for grins I sweep the altar, poking around. And there, not more than 50 feet from the pope, is the Time guy. The kicker was not just his proximity, but the fact that there was a cardinal holding an umbrella over him while he shot.

My mood turned black. I became aware of another shooter, who had wedged in next to me, when the railing we were using for camera support started shaking. This guy was huffing and puffing, shooting like mad, and the whole platform was quivering. I turned, ready to tear somebody a new one, and stopped.

He had like a Novosiberskoflex, or some East bloc camera with a preset lens about half the focal length of my rig. It was a single-shot camera, wired with a cable release he had taped to the lens barrel. He had no right hand. He would focus left-handed, and steady the camera with his stump, then squeeze the cable with his good hand. Then he would reverse the grip and advance the shutter with his stump. The rail was shaking because of all this maneuvering.

The man was working at a feverish pitch. This was his pope, his moment, his country. He was making pictures he would tell his grandchildren about. I stood there, with a camera store around my neck, on assignment for a major international publication, and I had peevishly stopped working.

I felt ashamed. I put my eye back in the camera.

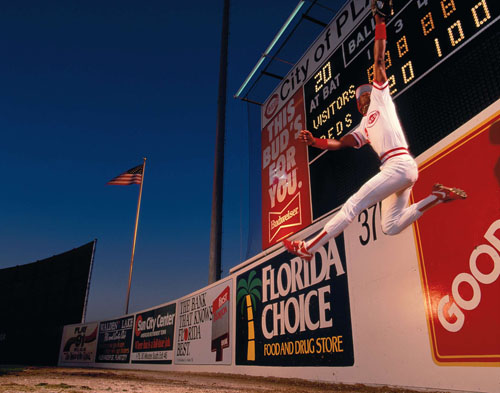

Listen to Your Assistant

Listen to your assistant. They can save your butt.

The baseball editor at Sports Illustrated looked at me and said, “I hate the baseball pictures. Go to Florida and make them look different.”

Turn the page and I’m at spring training, bombing around with a movie grip truck, an 18-wheeler, lighting up the Citrus League, doing simulated action pictures of the defensive stars of baseball. We shot them at dusk, after the games, and had to draw so much electric that we needed a truck with a 600-amp generator so we could fire the 10 to 15 2,400-watt-second Speedotrons we were routinely using.

Shot Eric Davis of the Reds, star outfielder, stellar defender, specialist at the leap-at-the-wall-rob-your-ass-of-a-home-run move. Which is exactly what we set up.

We lit up the outfield, got Eric out there, tossed a ball up to the wall, and he’d leap spectacularly and grab it. You’re out!

“Listen to your assistant. They can save your butt.”

I was shooting a Mamiya RZ with a 50mm lens, on a sandbag lying on the grass. Things were going great. I had about 10 frames of Superman-type leaps. Small problem—they were all on one piece of film.

The Mamiya has this clutch button that if it’s depressed, you can fire the camera but not advance the film. Ideal for multiple exposures, if that’s what you’re in the mood to shoot.

My assistant on the job, Howard Simmons, who has gone on to a terrific career as a staffer at the Daily News, was roaming, as all good assistants do. He bent over to check the camera I was shooting. I heard a gasp. He whispered in my ear, “We have shot no film.” He left out the “dumb$#!%” part, which I appreciated.

Whaddaya do? Eric was ready to leave. He was huffing and puffing. “Uh, hey, Eric, those looked sooooooo fantastic that I need to get just a few more on another roll of film. You know, just in case we lose the one we just shot.”

Or in case some idiot behind the camera made art when he should’ve been making pictures.

Eric Davis

Get a Camera Where You Ain’t

Sometimes the camera has to do all the work. You may have to do a lot of work to get that camera into the right spot, but then you just have to sit back and hope it all goes okay.

I worked for about three weeks to get this camera attached to the frame of a T-38 during a flight with Senator John Glenn in the back seat. Anything that gets attached to a tactical aircraft has to go up, down, and sideways through an approval process.

Then, when you get the approval, ya gotta figure out a way to make it stay put while the flyboys are up there rockin’ and rollin’.

It would not have been a good day in the field if this camera had gotten loose in the cockpit.

The NASA engineers were great about it, devising plates and bolts to get it tucked away safely. This particular shot was with a Nikon N90 and a 16mm fisheye.

Senator Glenn and I shared a credit in the magazine on this, which was a cool thing. I told him, “John, just squeeze the button (on a remote cord run to his fingers) and look toward the light.” He did it perfectly.

Working with the Senator was one of the honors of my career. He was great about being photographed. I always teased him that he had gone to the Ralph Morse School of Being a Photo Subject.

“Sometimes the camera has to do all the work. You may have to do a lot of work to get that camera into the right spot, but then you just have to sit back and hope it all goes right.”

John Glenn

Take a Chance

When I got offered three weeks of day rates to shoot the first launch of the space shuttle, I walked into my job at ABC television and quit. I promptly converted those day rates to a plane ticket to Northern Ireland. It was 1981 and the hunger strikers in the H blocks were about to die. The place was gonna blow.

I went over with my bud Johnny Roca, a Daily News shooter. He was great companionship. We’d be in the middle of a riot, rocks and bottles everywhere, rubber bullets flying, and he’d nudge me, “Joe, you can’t believe the blond in the upstairs window across the street.”

It was back in the day when ABC had a trio of anchors: Frank Reynolds in Washington, Max Robinson in Chicago, and Peter Jennings in London. They only moved these guys out from behind the desk for a really big story. Sure enough, they moved Jennings to Belfast. My old boss at ABC got word to me to try to get a photo of Jennings. A day rate is a powerful motivational tool when you’re broke, so I promptly looked him up.

He was cool with it. I ended up photographing him numerous times during his career. He was a good news-man, and always decent to work with and easy to make a picture of. He said to me in Belfast, “So what they want here, Joe, is the trenchcoated anchorman on the streets of the war-torn city, right?” I nodded.

The North calmed down and I headed for London. ABC contacted me again. Shoot Jennings at the bureau. I walked in, and five minutes later, the wires started clacking furiously. The pope had been shot.

“This is the type of business where you have to make uncertainty your friend.”

“Jennings told me I could come with him to Rome. I called my agency in N.Y. They were screaming, ‘Go, go!’”

Jennings told me I could come with him to Rome. I called my agency in New York. They were screaming, “Go, go!”

I arrived in Rome in the wee hours aboard a private jet with Jennings, his producer, and myself. Peter checked me into the Cavalieri Hilton, one of the nicest hotels in the city. I had a maxed out credit card and about 10 bucks in my pocket. My agency wired me money the next day. I spent the next two weeks in Rome on assignment for Newsweek and Bunte magazines, the same magazines that had picked me up in Ireland.

I went broke and without prospects, and came back with a freelance career started. As fellow shooter Keith Carter is fond of saying, this is the type of business where you have to make uncertainty your friend.

The Best Pictures Are Right Under Your Nose

Claire

You don’t have to go to Afghanistan to shoot good photos. The most important pictures you will shoot are right there in front of you, of the people and places closest to you.

My kids and I were at Walt Disney World, at the hotel pool. Claire, about eight at the time, decided to be a torpedo and pushed off the bottom in the nine-foot-deep section to zoom to the surface. Thing is, she zoomed at an angle, not a straight line, and her face crashed full speed into the wall of the pool. Ouch.

After we got everything calmed down and figured out no permanent damage had been done, I pulled out a Coolpix to JPEG a damage report to her mom. (This was my first vacation as a divorced dad with just me and the kids. Figures.)

The result was one of my favorite pictures. At a tough, painful moment in her young life, Claire looks back at the camera undaunted and unbowed (you lookin’ at me?). Her eyes are deep pools of resolve. I suspected then, as I do now, that Claire will live life on her own terms, and won’t take much grief from anyone. (Uh, this would include her dad.)

Lovely, intimate bits and pieces like this are the glue that hold together the scattershot life of a photog. In my helter-skelter pursuit of “big” pictures, I ignored too many quieter, close-to-home moments. As I look back, I wish I had more of ‘em. Especially now, ‘cause my kids won’t put up with me pointing a camera at them anymore.

“In my helter-skelter pursuit of big pictures, I ignored too many quieter, close-to-home moments. As I look back, I wish I had more of ’em.”

Learn from Those Around You

“Like I said, there ain’t nobody like him.”

Face it, Walter Iooss is the coolest photographer walking. I mean, he’s just Walter, man, and there ain’t no other.

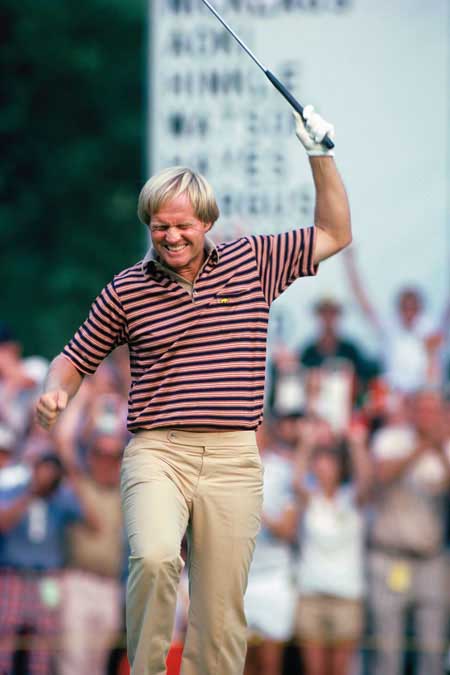

I was assigned to shoot the 1980 U.S. Open Golf Championship out in New Jersey. I had never shot a golf match before in my life. I had no idea what I was doing.

But Walter Iooss did. So I stuck with Wally all day. Looking back, I was kind of blatant about it, but he didn’t seem to mind. I was a pup, and he was, you know, Walter, even back then. He had an assistant who carried only one camera, I think, with a 600mm lens. Walter would stride down the fairway unencumbered.

I was carrying all my stuff: a six, a four, a three, all with motors, wide glass, camera bag, strobe. It was tough keeping up, I tell ya. Walter takes one step to every four of mine.

We come to the last hole. Iooss gets a spot, and I’m right next to him. Nicklaus holes out and wins the tournament, and goes jubo right there. I get the only good golf frame I’ve ever shot.

Like I said, there ain’t nobody like him.

Jack Nicklaus

My Most Important Piece of Equipment

“She said, ‘It’s for luck, Daddy.’”

I was in the basement preparing to go off somewhere, as usual, and I was doing the checklist thing. You know: cameras, lenses, batteries, film, chargers, cords, bunny head....

Bunny head?

My daughter Caitlin was about three at the time, so I brought it upstairs and asked her about it. She said, “It’s for luck, Daddy.”

It’s much bedraggled now—it’s lost its eyes and mouth, and it could use a run through the washing machine. But it’s stayed in my camera bag through wind and rain, bad locations, Godforsaken places, dicey jobs, big jobs, small jobs, bad jobs, you name it.

Caitlin just turned 22.

Know Who You’re Talking To

“All the while I was sitting at the clink, waiting for news, these guys were home having wine and a nap, waiting for a call from their guy at the jail.”

Know who you’re talking to. Photo director and editor Rich Clarkson is fond of saying that, and you know, he’s right.

I was in Rome, young and single, on assignment for two weeks, waiting to see if the Pope was gonna die.

I would go to the hospital every day, and cover the press briefing. Then I would go to the Questura, where they were holding Ali Agca, to see if he would be moved and I could get a shot.

Boy, did this international news newbie learn some lessons! Every day, I would be by myself at the Questura. I would wait, and wait, and wait, and then nothing would happen and I would leave. The guards were amused, shaking their heads.

Then the perp got moved. And the place was packed when I got there! Italian photographers everywhere. Italian photographers with informers on the police force, that is. All the while I was sitting at the clink, waiting for news, these guys were home having wine and a nap, waiting for a call from their guy at the jail. They were plugged in and I was definitely not.

They moved Ali Agca and I got a picture. Along with a couple hundred other guys.

So between a stint in Northern Ireland and now Rome, I had been, as they say, on the road for while, you know what I mean? Every day I had to make a number of calls to the States, and I used the phones at the press area of the Vatican. They always gave me the same operator because she spoke English well. She would get on the phone with her lovely Italian accent, “MacNalli, always MacNalli,” she would say. Her voice sounded real nice.

So I mustered the best manly tones I could and asked, “Perhaps we could have dinner?” I could hear her giggling. “Oh, no MacNalli, I have no money!”

No problem, I said, I’ll spring for dinner! Ever the gentleman.

More giggling. “Oh MacNalli, you do not understand. We here at the Vatican switchboard, we are sisters!”

I hit on a nun. A new low.

Maybe One Day They’ll Think You’re Cool

Self-Portrait on Empire State Building

It’s tough being a photog dad. You miss a lot of first steps, ball games, recitals, birthdays. When your kids are young, they don’t care or understand that you’re trying to make a living. They just know that you’re gone.

You try to make up for it in little ways. They become travelers along with you, sometimes. They hopefully get a sense that this is a larger world. They (occasionally) think it’s cool when you show them a cover or a picture of somebody famous.

And maybe, just maybe, years from now, they’ll look up at the blinking light atop the Empire State Building and know that their names are inscribed there.

“Caitlin and Claire...your daddy loves you.”

“When your kids are young, they don’t care or understand that you’re trying to make a living. They just know that you’re gone.”