Let’s call it Louie’s East, in honor of that semi-famous dive that used to be on the corner of 41st and 2nd Avenue and which served as the unofficial watering hole, hideaway, strike war room, and confessional of the New York Daily News. Often, as a copyboy, I would be dispatched to the third floor, where in the din of presses that at the time jack hammered out over a million papers a night, I would pick up a few dozen one-stars, the Bulldog, the first edition of tomorrow’s paper.

Next stop, Louie’s East. I would not return to the seventh floor newsroom. I would go downstairs, cross the street, and walk through the doors and into a solid wall of stale beer smell. I would then walk along the bar and distribute papers, and editors would phone in their corrections over a boilermaker or two.

I’m not disparaging the place unfairly. It actually reveled in how scruffy it was. There was graffiti in the men’s toilet that read, “Don’t do no good to stand on the seat...the crabs in here jump 10 feet.” I shit you not, to continue the visual.

It was part of the mix, the culture of New York journalism. Here would mix poets and scribes and columnists and editors and photographers, all reveling together in the imperfect and wonderful occupation of telling stories. It was here I think I first heard that old New York tabloid mantra: “Some facts are too good to check....”

Tales got told. Here are a few...

Fighter pilots are great. Until they get to know you, they’ll use that responsible, technical military speak.

“Yes sir, the back seat of a tactical aircraft does present a dynamic environment for the shooting of photos.”

Uh, that means I’ll be hanging onto my a$$ while I throw up through my nose, doesn’t it?

“Yes sir, it does, sir.”

I was assigned to shoot a story on the 100th anniversary of flight for National Geographic, so I knew I was going to have to do some flying. Thankfully, Bill Douthitt, my editor, was smart enough to know I had to train up. He allotted some budget money for me to get some time in civilian aerobatic stunt planes.

I started flying in an Extra 300, which is basically an engine with wings. It was a tough stretch. Every morning, I would wake up knowing I was gonna retch my guts out at least two or three times. But I had to do it. I couldn’t have my head between my legs while I was supposed to be shooting.

The pilot who flew me was great. He gave me the stick and pushed me to fly high-G maneuvers, all the while looking out of the aircraft and identifying what I was seeing on the horizon. It developed what pilots refer to as “situational awareness.”

It helped me survive my flights and come back with pictures. I ticked over 9.2 Gs once or twice, and thus became familiar with the anti-G straining maneuver, which means to tense the entire lower part of your body, from your toes right up through your gut, all the while grunting and breathing in explosive gasps.

Pilots, when they drop their reserved use of language, will refer to it as, “cracking a walnut with your butt cheeks.”

“I started flying in an Extra 300, which is basically an engine with wings. It was a tough stretch. Every morning, I would wake up knowing I was gonna retch my guts out at least two or three times. But I had to do it.”

Jenny Gutierrez

I never ask someone to do something for the camera I wouldn’t do. This has gotten me into trouble. Trying to combine the water and bike elements of the triathlon, I thought Jenny Gutierrez, America’s representative in the women’s triathlon for the Sydney Olympic Games, could pedal a bike off a diving board into a pool, and I would be at the bottom photographing her descent, backlit with strobes, in an explosion of bubbles.

“I never ask someone to do something for the camera I wouldn’t do. This has gotten me into trouble.”

Crazy as it sounds, I got on the bike and started to demonstrate how I wanted this to go, oblivious to the idiocy of me showing an Olympic athlete how to do something physical. I was about halfway down the board when I realized I didn’t have nearly enough speed to clear it. The front wheel went off, the gear chain hung up on the end, and I pitched headfirst toward the water.

Thing was, the back end of the bike whipped around at frightening speed, and smacked into me. Right between the legs. While I was at the bottom of the pool, I was in so much pain I actually considered drowning. I mean, if I just died, the pain would stop, right? (My wife, Annie, was horrified at this story when I told her, mostly at my stupidity and the possibility I might have been seriously injured. “You’re lucky the bike didn’t crack you right in the head!” she exclaimed. I told her that would have been preferable.)

In retrospect, they should’ve just said “yes” right away. I’d been inserted in the loop by National Geographic as the official NASA photographer of record for STS-95, better known as John Glenn’s return to space. So I figured I’d (de facto) be able to dive in the NBL (Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory), which is where astronauts train for weightless EVA assignments. An EVA (Extra Vehicular Activity) means the astronaut is outside the shuttle or International Space Station (ISS), fixing or attaching something. So, you train in the NBL to do an EVA to fix the ISS. Welcome to NASA....

They said no. I wasn’t trained, it wouldn’t be safe, and they could shoot the picture for me. Maybe when I’m in the field for the Geographic I feel the weight of 15 million pairs of eyes counting on me, and I’m not going to take no from a mid-level government functionary who wants to have an easier day. Maybe it’s because I was raised Irish Catholic and grew up with a terrible resentment of authority. Maybe it’s because I devoured lots of comic books as a kid and just wanted to go diving with the spacemen. Whatever. (I have teenage daughters, so I say that a lot.)

I took the written commercial diving test. I took the swimming test. I took the diving test in the pool, which, by the way, is 100′ × 200′ × 40′ deep. After about five weeks of mulling this over, NASA finally broke down and said “yes,” and gave me a date to dive.

First call I made was to Pete Romano, one of the great guys in the underwater lighting business, who runs Hydroflex on the West Coast. Every time you go to the movies and see an underwater sequence, you will see Pete’s name roll in the credits. He’d just finished the lighting for Clint Eastwood’s Space Cowboys movie, part of which had been shot in the NBL, and his lighting units had been safety certified by NASA.

That’s critical. If it’s not safety certified, it doesn’t go in the pool. I rented his lights and he came to Houston for free to help me.

But underwater HMIs just lift the level a bit and don’t really give you truly shootable light. The real punch had to come from strobes. There is a structure that runs along one of the 200′ sides of the NBL, and I put ten 2,400-watt-second units atop it. A challenging aerobic workout, but how do you trigger those puppies so you can actually make a picture?

Here’s where it got interesting. I went to 40 feet with a Nikon RS, a 17–35mm zoom lens, and a Nikonos strobe pointing not at my subjects, but straight up. At 20 feet there was a safety diver with another underwater strobe, also pointed up, slaving off my flash, which in turn triggered a master slave on the edge of the pool, which was linked to a battery-operated strobe on the pool deck, which was pointed at the office roof, triggering the 10 packs up there. Hellzapoppin!

I felt like a kid again, trying to make a radio out of coffee cans and string, but it worked. The film that usually comes out of the NBL is 1600 ISO color neg, murky at best. I came out of there with 100 ISO chrome shot at ![]() of a second at about 5.6.

of a second at about 5.6.

Here’s to Mark Sowa and Robert Markowitz, two technically inclined NASA shooters who have forgotten more photography than I’ll ever know, and to my grammar school nuns, who whenever they caught me with a Fantastic Four comic tucked into the pages of the social studies text, told me I would come to no good. Or maybe a career in photography, which is a lot about not taking no for an answer.

“A career in photography is a lot about not taking NO for an answer.”

“Like a Marine, you improvise, you adapt, you overcome.”

“Neither snow, nor rain, nor heat, nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds.”

Contrary to popular belief, that’s not the official U.S. Postal Service motto, but is paraphrased from the fifth century Greek historian Herodotus. As has been noted, Herodotus almost certainly never delivered a letter.

I can relate.

I was sent to El Centro, California, which is the winter home of The Blue Angels because of the non-stop blue skies. It never rains. I’m very wary of the word “never.”

I was shooting the Blues for a fashion story for Men’s Journal. I had one day to shoot it and one day only. The team was giving up their only day off, Sunday, to do this, and it was a big deal.

Unfortunately, that Sunday it rained more in El Centro than it had rained in the previous 10 years. I kid you not. It was a non-stop downpour.

Now a good rule of thumb to observe when working with the military is, no whining. Like a Marine, you improvise, you adapt, you overcome.

Or, you use strobe.

Sometimes you just have to draw the line with your subjects and try (respectfully, logically) to use your power as a photographer—an image maker—to lead the subject where you want the shoot to go.

After I shot the U.S. Olympic team in the nude in ’96, I became the “Naked Guy.” Hence Time Canada called me to shoot two Canadian Olympians from the 2000 Summer Games, nude, for a cover. One was a female water polo player, Waneek Horn-Miller, an Aboriginal Canadian and a political activist. (A very serious activist. As a child at a rally for Indian rights that turned violent, she had been injured by government troops.)

The Canadian flag is great to shoot. I mean, it’s tough to beat that red and white leaf, ya know? So I had this huge flag lit up and glowing in the studio for a background. Her mom walks in, looks at it and says, “No way Waneek is posing with that flag.”

Waneek walked in a few minutes later.

“Not doing it with the flag,” she said flatly. “Roll it out.”

“Use your power as a photographer - an image maker - to lead the subject where you want the shoot to go.”

Hmmm. I wasn’t gonna cave, so I rolled the flag out and shot the assistant against white. Already had a shot with the flag, so I took the two very different Polaroids to the makeup room.

I looked at her and smiled warmly. “I respect your Aboriginal sensibilities,” I explained. “And I understand your passion for your cause. But the cover of Time is a bully pulpit and if you’re serious about ramping up awareness of Indian rights in Canada, this kind of exposure can only help.”

I showed her the Polaroid with the flag. “This gets you the cover.” I showed her the Polaroid on white. “This doesn’t.”

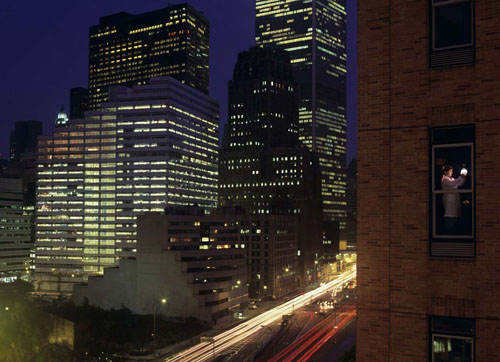

The beaker is filled with a mixture of water and milk, and the student is holding a small flash about the size of a golf ball. It makes the liquid glow like a sci-fi experiment, and also lights the kid’s face.

I’m on the rooftop of another building with a medium-format system, with multiple 2,400-watt-second strobes lighting the side of the building I’m shooting, and dragging shutter[1] for the city lights. I’ve got three assistants on radio giving the student his cues and watching the big strobes. This became the lead to a three-week effort on Stuyvesant High School, which Life put forth as perhaps the best high school in America.

[1] Dragging Shutter: Want more detail in the background when using flash? Use a slower shutter speed (known as “dragging the shutter”). This leaves the shutter open longer and gives you more ambient light.

The whole picture came down to a 10-cent flash powered by AAA batteries held in his hands.

I always tell my assistants: watch the lights. Make sure they’re firing.

When you have your camera to your eye, there is no way to tell if all your lights are firing in a multi-strobe setup. The last thing you want is a nasty surprise at the end of a shoot when you realize some background strobe nobody was watching was malfunctioning.

So, watch the strobes! But, just as importantly, listen to them. For example, when five big packs go at once, you cannot always tell which are firing by looking at the heads, but if something is wrong, you can pick up on the lack of pop. There is a reassuring “Pop!” when big packs fire and if you are not hearing that times five, there may be a problem.

“Watch the Strobes! But just as importantly, LISTEN to them.”

So, look and listen on the set.

“When you’re up to your a$$ in alligators, it’s often difficult to remember that your initial objective was to drain the swamp.”

That’s a reality of location work. How do you stay focused, project confidence, and have faith in yourself and your idea when everything around you is going to hell in a handbasket?

I was assigned to shoot “Sleeplessness in America,” yet another riff on the elusive idea of getting a good night’s sleep that magazines continually put on their covers because they know it sells. Who doesn’t wanna know how to get a better set of zzzz’s?

Call me twisted, masochistic, or just plain dumb, but my response to illustrate sleeplessness in the workplace involved a cast of 29 people, a crew of five, two Winnebagos, hair, makeup, and styling, a panel truck filled with photo gear, about 30,000-watt-seconds of strobes, one of the most famous intersections in America, the New York City Police department, location permits, about 10 hours of setup, and (mildly ironic) a sleepless night.

“No matter how nuts it gets out there, you just gotta laugh it off and keep pursuing the photo.”

About midway through something like this, a gator-filled swamp looks pretty darn appealing.

But that’s the deal. No matter how nuts it gets out there, you just gotta laugh it off and keep pursuing the photo. You gotta ignore those alligators.

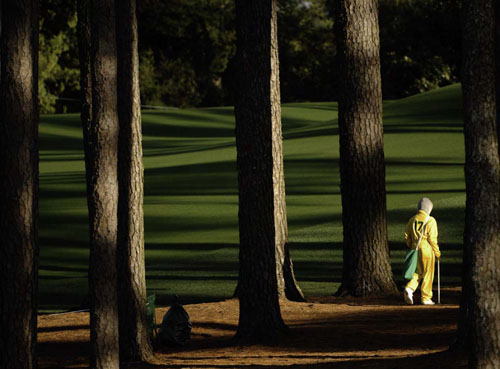

“Another rule at Augusta is photogs are not allowed on the course until after 8:00 a.m., just when the light starts to suck. I was coached by other shooters about how to get around this- talk to people, make friends, be, you know, Southern....”

Augusta National Golf Club is home to the Masters golf tournament, the famous green jacket, and more rules than the Pentagon. Within minutes of my very first ever arrival at Augusta, I was cordially accosted by what appeared to be a 16-year-old who had the face of a kewpie doll and the attitude of a dominatrix.

“Good mornin’, sir, I see ya’ll have a cell phone. Ya’ll have to check that cell phone,” she said. “Oh, I see now ya’ll a memba of the media. Ya’ll be allowed to keep that cell phone. But ya’ll need to register it and get a sticka. You’ll be escorted ova to that station. Now ya’ll can only use your cell phone within the confines of the press center. Ya’ll cannot use a cell phone outside the press center. Do you understand, sir?”

She kind of said “sir” the way a Marine D.I. says “maggot.”

Another rule at Augusta is photogs are not allowed on the course until after 8:00 a.m., just when the light starts to suck. I was coached by other shooters about how to get around this...talk to people, make friends, be, you know, Southern...you might could get on the course a few minutes early!

I’m from New York and I’m not that f-ing chatty that early in the morning, so I just went through the food service entrance. A few guys would be hanging around. “How you doin’? How you doin’? Hey, how you doin’?”

And then I’d get on the course and it would be complete darkness and nobody messes with a New Yorker in complete darkness.

I found a spot and waited for light.

It was the very first rodeo I’d ever covered, the grandaddy of ‘em all, out in Cheyenne, Wyoming. It’s funny when you’re a photographer out in the field and you’ve got the fever, you know? You come up with this idea you think no one else has ever thought of.

I thought it would be cool to stick my fisheye lens in between the slats of the bull chute and make a pic as the bull shot out of there—it would be all sorts of dramatic. I crouched down, got in position with my fancy motor-driven Nikon, and waited.

An old rodeo cowboy photographer with a Honeywell single-shot camera and screw-in 200mm lens was leaning against the fence. He looked over and gave a half smile. I was from New York, young and competitive, so I already felt myself getting ugly, thinking he was going to steal my shot or tell me how to do it better.

“Ya know what they do to make the bull come outta the chute?,” he asked. Of course I didn’t, being a greenhorn.

“Well, they hit ‘em with an electric prod...and that bull’s gonna shit all over the place.”

I looked around and realized where I was crouching actually smelled really bad.

I thanked him kindly and chose another angle. I’ve always been grateful to that man, because he could’ve sat back and had himself a really good laugh and a story to tell that night at the bar.

“‘Ya know what they do to make the bull come outta the chute?,’ he asked. Of course I didn’t, being a greenhorn.”

“We flipped the set, with my camera angle being where the action usually took place. Instead of looking into darkness, I’m looking at spectators.”

It’s always tough to shoot a stage production and get a sense of the audience. You have the seats, and usually a huge gap, and then the stage, and then some more space, and then the actors. Most photo attempts at this have a big hole in the middle.

Unless you can turn things around.

I was on assignment for National Geographic Traveler to shoot the Disney-MGM studios. One of the big shows there is the “Indiana Jones Stunt Spectacular.” It’s a huge set, and sort of fun to look at, but the action is spread out and distant.

This was back when Disney would actually jump to it for a major publication. I suggested we stage a show at night, just for photos, and I’d actually be on the set, using a long lens and shooting back into the audience. We’d have to manufacture an audience and redirect the choreography of the show.

No problem. Disney put out the word for audience extras and about 500 or so people showed up. They gave me two pyrotechnic crews and a lighting crew, plus my own assistants, and a whole bunch of strobes.

We flipped the set, with my camera angle now being where the action usually took place. Instead of looking into darkness, I was looking at spectators. We set the actors in motion, leaping the fire. I ran five cameras per leap off of a foot pedal at various shutter speeds. Each camera caught the strobe exposure, freezing Indy and Marion as they escape.

You have to be really convincing and confident when you set this type of stuff up, ‘cause people are working really hard, and lots of dough is being spent, and there is no guarantee the picture will even get published. Thankfully, this one did.

I spent the week shooting for the book Passage to Vietnam on the back of my fixer’s motor scooter in Hanoi. We did a number of jobs, some arranged, others just knocking around. While driving, a couple of ladies in traditional dress passed us in traffic on another scooter. We started following them, and I was making pictures and they were laughing.

My fixer turns and says, “It’s a wedding. Do you want to go?” Vince Vaughn and Owen Wilson aside, where I come from, you just don’t crash a wedding and start shooting pictures. “Can we do that?” I asked.

“No problem,” came the reply. In Vietnam, everybody’s on a scooter or a bike, except the wedding party. On this special day, they get one huge car and stuff everybody they can in it. Sure enough, the wedding limo comes by us on the street, and my fixer maneuvers our little motorbike next to it and gestures to roll down the window. Rapid exchange of Vietnamese.

“We’re invited,” was all he said.

I spent the day as a guest of honor at this wedding of complete strangers. I was never more graciously treated in my career. I stayed with the bride and groom right till that emotional moment where reality hits the bride that she is now with this man, in a new home. Just an amazing day, one of those gifts you get when you have a camera in your hands.

“I spent the day as a guest of honor at this wedding of complete strangers. I was never more graciously treated in my career.

I stayed with the bride and groom right till that emotional moment where reality hits the bride that she is now with this man, in a new home.”

It’s important to get good advice as you start your career. I’d just been promoted at the Daily News to the studio (photo lab). In News parlance, I was still a boy. You weren’t a man until you went on the street as a shooter.

One of the older guys motioned me over. “One of dese days, kid, you gonna be sent to shoot da perpetrator. And you know, he ain’t gonna wanna be shot. He’ll be coverin’ himself up. People screamin’ and shoutin’ all over da place. Police pushin’, tryin’ to get the scumbag outta da precinct.”

He looked at me intently, jabbing his finger at me for emphasis. “Dis guy ain’t gonna want his picture taken, ya know, like I said. So you wait, real calm. Ya got the camera around ya neck wid a wide lens and a big flash, but you don’t even got it to your eye, ya know? It’s just there, hanging around your neck.”

“But you’re ready, ya know, kid?” he continued. “Dat guy comes by you and he’s all covered up, people screamin’, and you just say to him, quiet like, real conversational, like you know ‘im, you just say, ‘Hey, $#!%head.’”

“And I swear ta God, kid, dat guy’ll look at you! Hit the shutter, and BANGO! You got an exclusive!”

This was substantially different in tenor and tone than the advice I got in photo school.

“You just say to him, quiet like, real conversational, like you know ’im, you just say, ‘Hey, $#!%head.’”