“Get your camera in a different place.”

Face it, everything’s been seen and everything’s been shot. So how do you make a different picture—especially of changing a light bulb? Climb the Empire State Building!

As maybe Napoleon thought when he invaded Russia, what could go wrong? Plenty. Rain, fog, ice. I climbed that puppy four times and on the last climb, on the last day, I got a frame.

A bunch of frames really. When the light levels of the bulb and the skyline crossed favorably, I was just ripping film.[1] I shot 14 rolls of 36 in about 10 minutes, shooting one-handed and leveraging myself back from the antenna and up above the bulb. Time to trust your ropes!

[1] Ripping Film: Shooting bursts of photos—you just keeping shooting without ever lifting your finger off the shutter. When you do this, a roll of 36 is gone, ripped, in around seven seconds.

You know, digital is a beautiful thing. Thinking back, I wish I had an 8-gig card. I changed out 14 film cassettes up there, and if I had dropped one, I’d be writing from a jail cell. Woulda killed somebody.

I waited six months, got aced out three times, have a two-inch scar in my scalp from putting my head into a girder climbing in the fog, really pissed off a bunch of TV stations in New York ‘cause I threw them off the air four separate times (you have to shut down the television signals up on the antenna or the microwaves will fry you), and National Geographic went way over deadline waiting for the shot, but I got a double truck[2] in the magazine.

[2] Double Truck: A double truck is a two-page spread, and photographers love double trucks because you get paid more—more space equals more dough. It’s that adage: “When you finally get it right—film is the cheapest thing you use.” Pixels are free.

Because I got my camera in a different place.

I can’t tell you how many pictures I’ve missed, ignored, trampled, or otherwise lost just ’cause I’ve been so hell bent on getting the shot I think I want.

You always have to go into the field with an idea. Hopefully, a good idea. But a good idea becomes a bad idea when you don’t see anything else.

So turn around. Look around. If you’re shooting wide, go long. If you’re at eye level, get on the ground. If you’re on the ground, call for a ladder. All of these strategies generally fall under the heading, “Why don’t I do my reshoot now?”

Turn around! And...if you hear music...listen.

“I can’t tell you how many pictures I’ve missed, ignored, trampled, or otherwise lost just ‘cause I’ve been so hell bent on getting the shot I THINK I want.”

I was slogging around a C-stand[1] and a strobe in the muck of the Savannah River, when I heard a saxophone. I turned, and there was a baptism march, heading for the river in the misty dawn.

[1] C-stand: A multi-part lighting stand with an extender arm. It’s very solid and very heavy, but very adjustable. C-stand stands for Century stand, which is an old term from the movie industry from a time when these stands were generally 100″ tall.

Fast as my hip waders would allow, I scrambled up the bank and grabbed a tripod and my camera, which was blessedly loaded with tungsten film. I cranked a few frames in the low light.

The bluish nature of the film played well in the pre-dawn. The slow shutter made the marchers shimmer. It was the picture of the day and the day hadn’t even started.

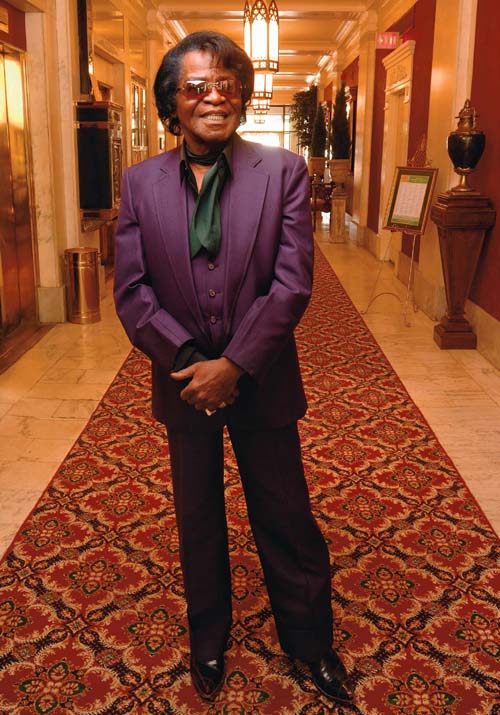

I was doing a story on Augusta, Georgia, while James Brown was still alive. He was Augusta’s favorite and most famous son, so this is a picture you need, right?

Called his agent. Kept calling. Every day. For six days. Message after message. Sometimes we’d talk and I’d push as hard as I could. Got nowhere.

Then, my phone went off, and it was the agent. “If you can be in downtown Augusta in 20 minutes, James will do this picture for you.”

I was like a cartoon character. I sprinted out of Augusta National Golf Club to my truck and got to the address she had given me in less than 10 minutes. That gave me 10 minutes to location scout, set up, and be ready to shoot.

Thankfully, the location was a pretty ornate building lobby. I walked in, and realized I had to make a stand right there. So I started moving furniture out into the street. (Try that in New York.)

“I had no contacts, no permission, no one to ask permission from... things get real simple when you have no time.”

I had no contacts, no permission, and no one to ask permission from, so I just did it. Hauled out a couple of chairs, signs, you name it. I threw up a medium softbox on a C-stand. Had no idea if that was the right light, but things get real simple when you have no time.

Had just set the light and turned around, and there he was. Purple suit, green neck scarf. He offered a handshake. He said,“Hi, I’m James Brown.” I looked back and said,“I know.”

The long hallway saved my butt ‘cause through the far doors is bright, bright sunlight. Backlight’s done! Drag shutter[1] and the whole hallway’s lit. Angled the softbox over him, just barely out of frame. You can see it in the top of his ultra-cool specs. In a corporate shot, this hit in the glasses is cause for concern. With James Brown, you can get away with it.

[1] Dragging Shutter: Want more detail in the background when using flash? Use a slower shutter speed (known as “dragging the shutter”). This leaves the shutter open longer and gives you more ambient light.

I shot 12 frames, and he looked at me and said, “Now, I thought you were a nice man, but here you go shooting all these pictures of me.” I knew the session was over. Grabbed a 105mm lens, shot a couple tight frames, and I thanked him.

The Godfather of Soul! He was dead a few months later. This just might have been his last formal portrait.

James Brown

“Tom Kennedy, the former DOP at National Geographic, always used to tell me to Pay attention to the small pictures.”

Tom Kennedy, the former DOP[1] at National Geographic, always used to tell me to pay attention to the small pictures. They are the connective tissue that holds together the larger bones of the story.

[1] DOP is Director of Photography. He’s the guy that controls my air supply—he assigns the story, has control over the overall direction of the photography, and is the main tap. Everything flows from him.

On the story about ballerina Paloma Herrera, I had done grand, beautiful, soaring, magnificent. She was all of those, to be sure.

What I hadn’t done was a detail. Something small, intimate, telling. Hard to blame me for this, really. I mean, when you’re assigned to photograph the Concorde, do you shoot the landing gear?

Beauty and pain go hand-in-hand—especially in the world of dance. Paloma wasn’t happy about it, but I asked her to take off her shoes at the end of a workout. Her feet were a mess. I shot it flash-on-camera in about a minute. Not the best, nor the prettiest picture of the take, just the most important.

Paloma Herrera’s Feet

With major athletes, five minutes is a big deal. This picture I shot in about three minutes, and got a total of 17 frames. Because of his size, I put El Guapo (reliever Rich Garcés) in the middle with Pedro Martinez and Manny Ramirez on either side. Then I told Manny and Pedro to pull El Guapo’s ears, which they were more than happy to do. I got a reaction, got a picture, and they were gone. Play ball!

If you’ve only got five minutes, you’ve got to force an emotional response from your subjects that in turn will translate into an emotional response from your viewer. Humor is one of the biggest things you’ve got in your bag of tricks—if you can introduce a little humor into your photo, so many things can go to hell in a handbasket, and you still get a great picture. In public, these guys have got their game faces on, so when you capture them laughing, it makes them more human to the reader.

“It doesn’t matter if it’s only five minutes, as long as it’s the RIGHT five minutes.”

Manny Ramirez, Rich Garcés, Pedro Martinez

Jenny Gutierrez

You don’t want the reader to look at your pictures and say, “Well, he must have the light over here!” No. You want the reader to simply say, “Whoa, cool picture.” You don’t want them looking up the sleeve of the magician.

One of the dead bang giveaways occurs in a full-length picture when you don’t gradate the light. You put up the light on camera left, for instance, make it all nice, and the subject looks nice and the ground looks nice too, ‘cause it’s lit up with the same intensity, feel, and f-stop as the subject.

Bad move. Being careless like that creates an off-ramp for the reader’s eye to exit your photo.

Don’t pack up your camera until you’ve left the location.

I spent three days photographing Linus Pauling at his house in Big Sur and came up with some reasonable—but hardly exciting—pictures. Came time to leave and I had a Nikon FM2 still out, Kodachrome loaded, and a 20mm lens sitting on the front seat of the car.

Linus went to open the gate, and one of his frisky kittens scampered up the fencepost and onto his shoulder. I nearly broke my leg charging the scene. I got three frames before the cat got bored (or freaked out by my lunatic charge). I had the lead to the story just seconds before I was about to leave.

The fog turns the light into a softbox, so I shot it with just straight natural light.

“Don’t pack up your camera until you’ve left the location.”

Linus Pauling

“Shoot it now. Don’t ever assume you can do a picture ‘Later.’”

Don’t think you can come back tomorrow and get it. Won’t happen. Light won’t be there, subjects will have second thoughts, and there’ll be a parade right where you want to shoot. Don’t ever assume you can do a picture “later.”

I was doing a mood piece on the nutty disparity between the pomp, wealth, and circumstance of the Masters golf tournament and the hardscrabble town it calls home—Augusta, Georgia. Face it, the place doesn’t get its nickname, “Ugh-usta,” for nothin’.

One of the dismaying things that happened in the history of the Masters was when the PGA ruled that the golf biggies could bring in their own caddies and not use the local, mostly African-American, course caddies. The locals lost their biggest payday.

The old caddies tend to gather around a hole-in-the-wall place called the Sand Hill Grill, which has a painting of an Augusta National caddie on the side of the building. I was with Hop and Mark, two old Masters caddies. They had been tough to run down on the phone, and even tougher to find in person. I needed this picture. It was getting dark out.

I asked if we could meet the next day at sunset. “Sure, yeah, okay....” Both were nodding and looking off.

No way that was gonna happen. I dragged my lights out, and shot it right then and there.

Did I want to shoot at night on a dark street corner? No. But I needed this picture. I got lucky. The grill door opened and there was a guy at the bar.

Shoot it now.

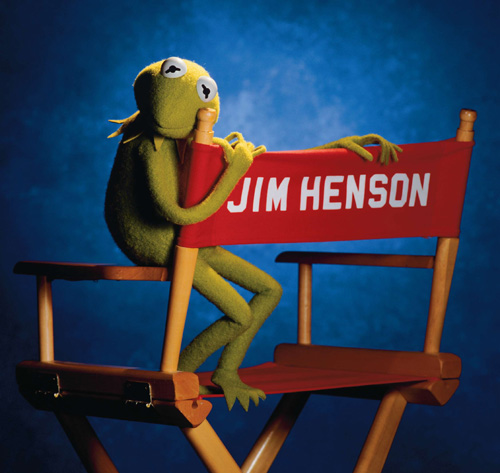

My first Life cover resulted from the tragic death of America’s muppeteer, Jim Henson. He died needlessly, of pneumonia of all things. It was a sad story.

The one bright moment was my daughter Caitlin, six at the time, started to realize that her photog dad actually did this sort of cool thing. While other dads were driving buses, or selling stocks and bonds, or listening to suits drone on at board meetings, her dad spent the day with a talking frog.

She brought the magazine into school for show and tell and told everyone, “My daddy took this picture. My daddy knows Kermit.”

So, if my editor hated the shot, at least I knew a bunch of six-year-olds loved it.

Which was good, ‘cause I was very nervous about this job. Sounds crazy, right? Why be nervous? I mean, Kermit’s a puppet.

When Kermit shows up, though, he’s got an entourage that would put JLo to shame. He’s got handlers, groomers, animators, and art directors. Also, because it was a cover, Life showed up with a bunch of opinionated folks.

So it wasn’t just me and the frog having a little chat. There were lots of folks on the set, almost all of them over the top emotionally because of Jim’s death. I had to light the job, shoot the job, but very importantly, I needed to manage the job.

Ya gotta keep your head on straight and remain confident behind the lens in a deal like this when everybody thinks you should shoot it their way.

Jim’s director’s chair was a given. Kermit perched on it with a soulful, sad expression. Huh? I swear, before this job I would’ve just thought a puppet is a puppet is a puppet. They’re not alive, so their expression doesn’t change. I couldn’t have been more wrong.

The muppeteers kept hovering, tweaking a finger, turning the head, bending a knee. I kept hearing, “Focus the eyes, focus the eyes.” They would respond to that by grabbing Kermit’s head and shaking it slightly, refreshing the position, and then walking away and looking back at him.

Dang! They would do this and I swear the little green guy would look better, more attentive, more emotional. It was amazing.

So, deep and dark and moody might be the way to go for a “sad” cover. But darkness can run counter to the purpose of the cover, which is selling the magazine. Magazines sit on the newsstands with hundreds of their competitors, every single one of them screaming for attention. You’ve often got to light one of these puppies not in the way you might like, but in a way that is going to pop and grab the attention of the harried commuter as he or she rushes past, giving each cover, oh, about a nanosecond’s worth of their attention.

“Ya gotta keep your head on straight and remain confident behind the lens in a deal like this when everybody thinks you should shoot it their way.”

“Keep pushing. ‘No,’ is ALWAYS the easiest answer.”

You have to keep asking questions on location. How does that work? When do you do that? Anything at all relative to this story that could possibly be pictorial in nature? Scientists are the worst. Their first response is generally, “Well, you can photograph me at my computer. How about that?” Then, during the day, if you keep pressing, they’ll say, “Oh, by the way, we’re going to blow up a tank with the world’s most powerful laser in a test chamber down the hall in a couple of hours. Would that interest you?”

Nahhhh! Let’s stay here at the word processor!

Keep pushing. “No,” is always the easiest answer. This picture is the inside of the test chamber at the National Ignition Facility in California, destined to be the world’s most powerful laser. It was sealed up and they didn’t want to take off the covers. Understandable, as they each weighed several tons and you needed a crane to remove them. They said, “You can photograph our computers!”

I said, “Take the covers off and let me inside, or I’m not coming.” They took two covers off. I dropped a light through one. One strobe pop filled the whole blessedly reflective chamber. Dropped myself through the other. Shot it wide. The picture ran double truck[1] in National Geographic.

[1] Double Truck: A double truck is a two-page spread.

“Shooting an Olympic athlete, on skis, on the edge of one of the most famous buildings in the world should be enough, but it isn’t. You still have to take the next step.

I had a magazine assignment to do a tongue-in-cheek look at the U.S. Winter Olympic Team, so I tried to find humorous or unusual situations in which to place the athletes. I always had a good relationship with the people who run the Empire State Building, so I asked if I could put a skier at the edge of the building. Surprisingly, they said yes.

We’re about 100 stories up and the wind is just howling, so it’s not the time for an umbrella or a softbox. I took a strobe (a raw light), positioned it to the right of the camera and put on a honeycomb spot grid[1] so the light wouldn’t spill over everything.

[1] Honeycomb Spot Grid: This is a new cereal from Kellogg’s (just kidding). It’s a circular metal grid (that looks like a honeycomb) that goes over your strobe head and limits the spread of the light. I use these when I want to concentrate light in a particular area and not flood everything with light.

You’d think it would be enough just to put her at the edge of the building, light her, and call it a day. When you’re looking at a truly “big picture” like this, as a photographer, it’s easy to forget about the details—but it’s those small details that will make the shot.

Look at the window to her left. Imagine the same photo if that window was black. It might just be me, but I hate to see a “dead” window in a photo. By putting a little light into it, the window comes alive and the picture has more depth. So I put a strobe head in there covered with a blue gel (I used blue because I thought blue would be a color that would naturally be there—plus I thought it worked well with her orange suit).

Once the lighting was in place, we put her in position, waited for dusk, and shot very quickly. It’s attention to little details, like that simple flash in the window, that take the photo to the next level. It wound up as a double truck in Life.

Donna Weinbrecht

You have to have faith in your ideas, ‘cause the next thing is you’re on the phone with a celebrity’s agent telling him you really think it’s a great idea to take the star and dangle her from a wire below a helicopter 500′ in the air over the Hollywood sign.

If you’re not passionate (and rational sounding), the next sound you’ll hear is “click.”

I was shooting a story for National Geographic called “A World Together,” and I needed to show the impact Asian actors and actresses were having on mainstream Hollywood movies. I wanted to work with Michelle Yeoh. She got her start in Jackie Chan flicks and went on to become a Bond girl, and starred in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon.

For the first shoot, I really did the Hollywood thing. I flew her out to a dry lake bed outside of L.A., got hair, makeup, and styling, the whole nine yards. Shot some lovely pictures, but my ever-direct editor at National Geographic basically told me they didn’t mean $#!& in terms of the story. He was right.

While we were out there, we tried an impromptu stunt from the helicopter. We stood on the skids, 150′ in the air, no wires or safety belts. Shot didn’t work. I was too close to her. But she proved to be beautiful, daring, and fearless. It got me thinking, always a dangerous thing.

Why not fly her on a wire off the chopper over the Hollywood sign? A shot that says, “Stunt actress. Hollywood,” all at once. Her people said no. She said yes.

I called my editor to explain. In between gales of laughter, punctuated by “you must be joking,” he said I could take a look. I would’ve usually just gone ahead. This time, I knew I needed permission. He was shocked. “I’m surprised you’re not calling me from the chopper, Joe,” he said.

Off we went. It was complicated. We needed FAA approval, a temporary helicopter base in the Hollywood Hills, the best stunt chopper pilot in L.A., the chief safety rigger from the movie Titanic, and an insurance policy that basically indemnified everyone living in L.A.

We got rigged and the chopper lifted off, slowly. Michelle and I walked underneath it, and we went flying. She was graceful and daring. We got a break with the light. The key to the picture was flying with her. I didn’t want to work long lens, ship-to-ship. I wanted to be right there and shoot wide-angle to retain the sweep and sharpness of the Hollywood sign.

When we landed, she laughed and told me, “You know, I’m scared of heights. I just don’t look down.”

The shot opened the Geographic story and got lots of comments, mostly from my colleagues who, after seeing me dangle on a wire from a helicopter, advised me to lose some weight.

“Why not fly her on a wire off the chopper over the Hollywood sign? A shot that says, ‘Stunt actress. Hollywood,’ all at once. Her people said no. She said yes.”

Michelle Yeoh

Jay Maisel always says to bring your camera, ‘cause it’s tough to take a picture without it. Pursuant to the above aforementioned piece of the rule book, subset three, clause A, paragraph four would be...use the camera.

Put it to your eye. You never know. There are lots of reasons, some of them even good, to just leave it on your shoulder or in your bag. Wrong lens. Wrong light. Aaahhh, it’s not that great, what am I gonna do with it anyway? I’ll have to put my coffee down. I’ll just delete it later, why bother? Lots of reasons not to take the dive into the eyepiece and once again try to sort out the world into an effective rectangle.

It’s almost always worth it to take a look. At the Lockheed plant in Marietta, I was told an F-22 Raptor, one of five flying at the time, was about to take off. It was the hot plane in the skies, still in test phase, so of course I said yes.

“Sometimes it’s all working for you and you still miss. Other times it all sucks and you get a terrific frame. You just never know. The one surefire way to get nothing is to not bother looking.”

I walked out onto the blazing tarmac at high noon, accompanied by a corporate shooter who kept assuring me I would get nothing. It’s bad, no, make that horrible light. It’s backlit. No color. We’re not going to get close to the plane. There was a whole litany of reasons why I shouldn’t bother. Every one of them was accurate.

I got one of the best pictures of the story, a shot that, for a time, was the best-selling cover of National Geographic, and ran inside as a double gatefold.[1]

[1] Gatefold: Fold-out page in a magazine that makes a two-page spread a three-page spread. A double gatefold, or double gate, is four pages across. Requires the photographer to make a long, skinny picture.

Sometimes it’s all working for you and you still miss. Other times it all sucks and you get a terrific frame. You just never know. The one surefire way to get nothing is to not bother looking.

By the way, the negatives about this picture were very real. I had bad light, no color, and couldn’t get close to the plane. What saved the shot was a 400mm lens. A long lens gives you compression, power, and distills the essence of the frame by isolating the center of interest and dropping out the background. All I had going were the graphics of the scene and the lens nailed them. Shoot this with wide glass, the picture goes away.

“The umbrella approach (appropriate for some instances, absolutely) scatters light everywhere. It’s indiscriminate, kind of like carpet bombing.”

Any idiot can put up an umbrella. One of those is writing this book. Done it plenty of times. Put up the old brollie and everything looks nice. Which may mean that everything looks nice, or that everything looks okay, which means everything sucks. Follow me?

Nice is nice, but it stops way short of fabulous. There’s the issue of control. The umbrella approach (appropriate for some instances, absolutely) scatters photons everywhere. It’s indiscriminate, kind of like carpet bombing.

So what if something in your picture’s got to look one way and something else has to look entirely different? Ahhh, there’s the trick! Put the umbrella away and go for the small softbox or the honeycomb spot grid.[1] Throw in a homemade gaffer tape snoot[2] and some black wrap, a few black cards to cut wall bounce, and now you’re cooking.

[1] Honeycomb Spot Grid: A circular metal grid (that looks like a honeycomb) that goes over your strobe head and limits the spread of the light.

[2] Snoot: Any device that forms a tube around your light source to funnel it and make it more directional. Could be a fancy Lumiquest store-bought snoot, or just some cardboard taped together. The function is to direct the light and control spill.

This picture of the amazed baby was made with lots of black lining the walls, soaking up stray light. It’s a double exposure, with a focus shift between the baby and the ball. You can do that on a set like this, when there’s a lot of dark area.

The whole idea was to show how babies register moving objects. So I needed:

(a) a relatively astonished baby, and

(b) a moving object. In one frame.

“Some rules are good ones, like the rule of thirds. It works. But, like all rules, ya gotta break it every once in a while.”

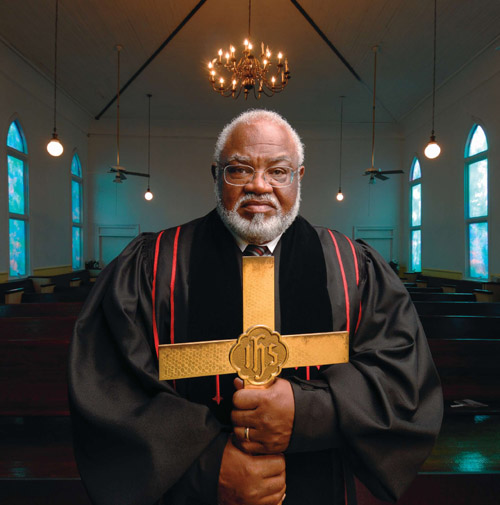

I was shooting in Augusta, Georgia, for Golf Digest. While wandering in a pretty poor neighborhood, I noticed a group of churchgoers. I walked into church with them and immediately liked the simplicity and strength of the place. I asked to meet the minister.

Pastor Grier and I sat and talked. I explained the story. He agreed to be photographed.

The pastor is a kindly man, but formidable looking. (Check out the size of his hands. I would not want to be a sinner in this minister’s congregation!)

“You gotta be loose, like a boxer - you have to bob and weave and slip and slide. The world doesn’t stay still. We can’t either.”

Technology is a wonderful thing and I love today’s zoom lenses. Can’t live without ‘em. But...the dark side of all this techie stuff is that we get lazy. Lots of photographers show up, stuff their tripod into the ground like they just struck oil, and work the zoom ring like it’s a knob on a freakin’ transistor radio. They have all the energy and mobility of a house plant.

You gotta be loose, like a boxer—you have to bob and weave and slip and slide. The world doesn’t stay still. We can’t either.

Get your hands on your subjects. Alfred Eisenstaedt, famed Life shooter, had a brilliant, simple strategy. He would stop the shoot, ask permission, and approach the subject. Then he would fuss over them—straighten a lapel that didn’t need straightening, pick off imaginary lint, brush away a wayward hair or two the camera wasn’t gonna see anyway.

He wasn’t doing anything practical. The subject would look the same after his primping session. But...he accomplished something very significant: he got his hands on them.

He broke down their defenses. He got up close and personal. They allowed him to touch them, the beginnings of trust. And he got a very positive interior dialogue going in their head. “Oh, I see. He wants me to look good! He’s on my side! Okay, he’s not the enemy.”

Try it. Then watch your subjects start liking the camera a whole lot more. Maybe not as much as Sophia Loren, one of Eisie’s favorite subjects, who has loved the camera her whole life (and the camera has returned the affection), but still, a whole lot more. And once your subject starts liking the camera, the camera likes them right back. Result? A good portrait session, as opposed to the photo equivalent of a root canal.

Sophia Loren

“There’s nothing as sweet and simple as basic human interaction. It trumps everything.”

Sometimes as photographers we almost insist on things being too complicated. We beat ourselves up because we think the simple solution isn’t good enough and the perfect photo is always out of our reach. When you’re in a tight spot (that would be most of the time), remember there’s nothing as sweet and simple as basic human interaction. It trumps everything.

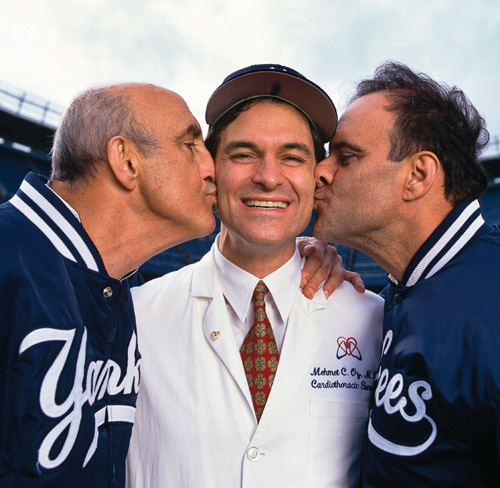

Here’s an example: I was assigned by Life to do a story on alternative medicine. One of the stars of that show at the time was Mehmet Oz, a doctor from New York-Presbyterian/Columbia Hospital who employed alternative and New Age medical techniques.

The famous Dr. Oz gave Yankees Manager Joe Torre’s brother, Frank, a heart transplant and got even more famous. My job was to get a picture of these three guys at Yankee Stadium. I was on the ball field at high noon. Far from ideal.

What do you do in five minutes with three pleasantly lumpy guys who are looking to you to tell ‘em to do something interesting?

As friend and mentor, Jay Maisel, always says, “Look for light, color, and gesture.” They’re the holy trinity of photography. In this situation, I went for gesture. It was all I had. I put Dr. Oz in between Frank and Joe. Then I smiled at them and said, “How ‘bout you guys give the doc a big Brooklyn smooch?”

Without hesitation, Frank and Joe planted wet ones on the doc’s cheeks and Oz lit up like crazy. I quickly dropped another roll in the camera.

My excuse to get people to do things again has been the standard: “You know, just in case the boys in the lab have a bad day, let’s just get a couple of frames on a different roll.” Always works. Face it, nobody wants to do this all over again, including me.

Another smooch. The doc beams. We’re done.

“That’s it? We’re done?” asked the Life reporter.

I was already packing up. Sometimes it doesn’t have to be hard.

Frank Torre, Mehmet Oz, Joe Torre

“I gave flashes to these body builders and told them to go light themselves. Trust Me, they were into it.”

Sometimes, especially when I am just plumb out of ideas (a not infrequent condition), I ask my subjects for help. I’ll pose them a question: “Is there any way you would like to be photographed that you have never been?”

Sometimes you get no answer. Other times, believe me, you get suggestions that would be unwise to follow up on. And, occasionally, you get a notion, a snippet of an insight that unlocks the door to a successful photo.

That’s one way of getting your subjects involved. Another is to make them actors on your stage and have them collaborate, physically, in the success of the picture. Body builders are like statues, monuments to physical perfection. They are like pieces of sculpture that, just like in a museum, need drama and highlights.

So I gave these body builders a mission. Light themselves. It involved them, and intrigued them, and in a way, made them the art directors of the photo. They would strike a pose and then light that pose. It was cool and it gave them something to concentrate on other than the cold ocean water I was asking them to stand in.

These little flashes are great. You can zoom them and control their spread and intensity. The generation of flashes we have now can be controlled wirelessly from the camera. You can push the output up or down, and never leave the tripod. That’s a significant advantage when the sun is sinking, the waves are sloshing, and your subjects are freezing.

You have to be able to turn on a dime.

I suggested a story to Life on strong women and singer-songwriter Fiona Apple fit the bill. Perfect, since she was riding her Tidal wave of success.

Fiona had always been shot as a waif—tendrils of hair blowing (dressed in lingerie), out in some sort of lily field. She told me she wanted to chuck that scene and be a warrior woman in a suit of armor. I was like, “Cool, babe, works for me!”

We did the whole Camelot thing in a daylight studio. A big deal with hair, makeup, styling, painted backdrop, falling rose petals, fake blood on the sword, catering, crew, managers, hangers-on. Everything. All the while, her manager is heating up about how late it’s getting. I was like, “You brought her late, okay?”

Finally, he explodes and says, “Gotta go now and the subway is the only way.” (It was rush hour in New York and she had a gig in Jersey.) I looked at Fiona over the camera, “Get on the subway in the armor?”

“We bolt and slip her through the turnstiles - sword and all - unnoticed. Subway came right away and I started ripping film like crazy for five stops. On the train, New Yorkers, true to form, avoided eye contact.”

I shout for a camera, wide lens, hot shoe flash, green and magenta gels, and a bunch of 100-speed 35 chrome. We bolt and slip her through the turnstiles—sword and all—unnoticed. Subway came right away and I started ripping film[1] like crazy for five stops. On the train, New Yorkers, true to form, avoided eye contact.

[1] Ripping Film: Shooting bursts of photos—you just keeping shooting without ever lifting your finger off the shutter.

The studio shot went away and the subway shot (flash-on-camera, ![]() of a second at f/4, a hand-held mess of a photograph) ran as the lead.

of a second at f/4, a hand-held mess of a photograph) ran as the lead.

You never know.

Fiona Apple

No matter how much crap you gotta plow through to stay alive as a photographer, no matter how many bad assignments, bad days, bad clients, snotty subjects, obnoxious handlers, wigged-out art directors, technical disasters, failures of the mind, body, and will, all the shouldas, couldas, and wouldas that befuddle our brains and creep into our dreams, always remember to make room to shoot what you love. It’s the only way to keep your heart beating as a photographer.

This kid is 15 years old, and I literally thought an angel had walked into the room. She shook my hand, she was completely comfortable, and from the moment she stepped on the seamless, she owned the camera. The sweet simplicity of the photograph belies the complexity and hard work just below the surface.

“The only way to keep your heart beating as a photographer is to shoot what you love.”

Believe it or not, she’s standing on white seamless paper. I always advocate independent control of the light on the foreground and background, and in this case, because of the environment, I lost control of the background. The enemy here was the big white box of a ballet studio I was shooting in. White walls, a white ceiling, so the light from the strobes bounced everywhere and onto the white background, which was not what the art director wanted. How do you tame the background?

[1] Octabank: A large softbox, slightly over 6′ wide. A source of very soft, reflected light. An industry standard for both studio and location portraiture.

[2] Lastolite Panel: A kit that has both diffusion and reflective material that fits onto a rigid, collapsible frame. Comes in 3×3′, 3×6′, and 6×6′ sizes. Ideal for diffusing or flagging light sources, or simulating window light. Breaks down into a small, light duffel bag. Very roadworthy.